Abstract

While loss of insight of cognitive deficits, anosognosia, is a common symptom in Alzheimer’s disease dementia, there is a lack of consensus regarding the presence of altered awareness of memory function in the preclinical and prodromal stages of the disease. Paradoxically, very early in the Alzheimer’s disease process, individuals may experience heightened awareness of memory changes before any objective cognitive deficits can be detected, here referred to as hypernosognosia. In contrast, awareness of memory dysfunction shown by individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is very variable, ranging from marked concern to severe lack of insight. This study aims at improving our mechanistic understanding of how alterations in memory self-awareness are related to pathological changes in clinically normal (CN) adults and MCI patients. 297 CN and MCI patients underwent PiB-PET (Positron Emission Tomography using Pittsburgh Compound B) in vivo amyloid imaging. Amyloid burden was estimated from Alzheimer’s disease vulnerable regions, including the frontal, lateral parietal and lateral temporal, and retrosplenial cortex. Memory self-awareness was assessed using discrepancy scores between subjective and objective measures of memory function. A set of univariate analysis of variance were performed to assess the relationship between self-awareness of memory and amyloid pathology. Whereas CN individuals harboring amyloid pathology demonstrated hypernosognosia, MCI patients with increased amyloid pathology demonstrated anosognosia. In contrast, MCI patients with low amounts of amyloid were observed to have normal insight into their memory functions. Altered self-awareness of memory tracks with amyloid pathology. The findings of variability of awareness may have important implications for the reliability of self-report of dysfunction across the spectrum of preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Amyloid, Anosognosia, Hypernosognosia, Metamemory, Mild Cognitive Impairment

1. INTRODUCTION

The capability to accurately assess our own cognitive abilities is crucial for us to function effectively (Clare, Whitaker, & Nelis, 2010; West, Dennehy-Basile, & Norris, 1996) and may be particularly important in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease, when deterioration in mental capacity can threaten the most basic everyday functions (Rosen, 2011). Lack of awareness, or anosognosia (Babinski, 1914; McGlynn & Schacter, 1989), of memory or behavioral deficits is a common and striking symptom in Alzheimer’s disease (Agnew & Morris, 1998), and has major clinical relevance since it is directly related to the reliability of a patient’s complaints of dysfunction (Kalbe, Salmon, Perani, Holthoff, Sorbi, Elsner, et al., 2005). However, the evolution of altered self-awareness of memory function across the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease is not fully understood. Specifically, the pathology underpinning the differences in awareness of memory function across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum remains to be elucidated.

Previous research has estimated that as many as 80% of individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at the dementia stage have some form of anosognosia (Reed, Jagust, & Coulter, 1993), and the disorder has been shown to correlate with overall disease severity (Kalbe, Salmon, Perani, Holthoff, Sorbi, & Elsner, 2005). In contrast, awareness of cognitive dysfunction shown by individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is very variable, ranging from clear insight and marked concern about cognitive difficulties (e.g. Kalbe, Salmon, Perani, Holthoff, Sorbi, Elsner, et al., 2005) to severe lack of insight (e.g. Galeone, Pappalardo, Chieffi, Iavarone, & Carlomagno, 2011) but see also Roberts, Clare, and Woods (2009)). The findings of variability of awareness may have implications for the use of subjective memory complaints in the diagnostic criteria of MCI, as anosognosia may reduce the validity of the subjective experience of cognitive abilities. In fact, anosognosia is beginning to be recognized as an important clinical symptom of MCI, that may predict greater progression to Alzheimer’s disease dementia (e.g. Tabert, et al., 2002).

Paradoxically, very early in the Alzheimer’s disease process, individuals may experience heightened awareness of subtle changes in their memory function, despite performing well on standardized memory tests. Previous studies have estimated that the prevalence of memory complaints in the non demented elderly population range between 22 to 56 % (Jonker, Geerlings, & Schmand, 2000). Often referred to as Subjective Cognitive Decline, accumulating evidence suggests that these individuals have an increased likelihood of harboring biomarker and neuroimaging abnormalities consistent with Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Amariglio, et al., 2012; 2015; Palm, et al., 2013; Perrotin, Mormino, Madison, Hayenga, & Jagust, 2012; Saykin, et al., 2006; Striepens, Spottke, et al., 2010; van der Flier, et al., 2004) as well as an increased risk of prospective Alzheimer dementia (Jessen, Wiese, Bachmann, & et al., 2010; Jessen, Wolfsgruber, et al., 2014), consistent with the concept of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (Sperling, et al., 2011). Of note, previous studies on Subjective Cognitive Decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease have been defined by self-reported cognitive concerns in otherwise unimpaired older adults (Jessen, Amariglio, et al., 2014). Whether or not Subjective Cognitive Decline should be considered a reliable precursor of Alzheimer’s disease, especially in the prodromal phase of Alzheimer’s disease, is a matter of controversy. Thus, in line with this, recent publications have called for studies to investigate the concurrent relationship between subjective and objective cognitive performance along the axis of Alzheimer’s disease development (Dalla Barba, La Corte, & Dubois, 2015; Jessen, 2014; Jessen, Amariglio, et al., 2014). In particular, it has been suggested that the association between awareness of memory function and pathophysiological changes across the Alzheimer’s disease stages will help discriminate individuals who are likely to progress to Alzheimer’s disease dementia from those whose awareness of memory is not associated with an underlying neurodegenerative pathology.

In the search for brain changes that contribute to altered awareness, as seen in Alzheimer’s disease, evidence from several lines of research have demonstrated an association between anosognosia and dysfunction in frontal, temporomedial and temporoparietal regions (Prigatano, 2010; Starkstein & Power, 2010). These observations overlap with brain regions that have been implicated in self-referential processing in normal individuals (Johnson & Ries, 2010; Northoff & Bermpohl, 2004; Northoff, et al., 2006; Schmitz & Johnson, 2007) and have been shown to be affected by Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Buckner, Andrews-Hanna, & Schacter, 2008; Buckner, et al., 2009), such as amyloid beta (Aβ) (Edison, et al., 2007; Engler, et al., 2006; Forsberg, et al., 2008; Kemppainen, et al., 2006; Klunk, et al., 2004; Mintun, et al., 2006). To date, the relationship between amyloid pathology and memory self-awareness in the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease has not been investigated.

The aim of the current study was to investigate self-awareness of memory function across the preclinical and prodromal phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Specifically, we wanted to improve our mechanistic understanding of how alterations in memory awareness are related to amyloid pathology across cognitively normal adults and MCI patients.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Design

This was a cross-sectional study comparing awareness of memory functioning in cognitively normal older adults with and without amyloid deposition and individuals with MCI with and without amyloid deposition. IRB approval was granted by the Partners Human Research Committee at the BWH and MGH (Boston, MA). Informed written consent was obtained from every subject prior to experimental procedures.

2.2 Subjects

A total of 297 English speaking participants, 262 CN (mean age 73.1 ranging between 60–90; 59.2% where women) and 35 patients with MCI (mean age 73.9 ranging between 53.5 to 84.8; 40 % were women) participated in the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the whole sample and by groups

| Total | Cognitively normal | Mild Cognitive Impairment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Aβ − | Aβ + | Aβ − | Aβ + | ||

| N | 297 | 199 | 63 | 15 | 20 |

| Age, y | 73.2 (6.5) | 72.5 (6.2) | 74.9 (6.2) | 74.9 (7.1) | 73.1 (8.5) |

| Female, % | 56.9 | 59.2 | 58.7 | 53.3 | 30.0 |

| Education, y | 15.7 (3.1) | 15.5 (3.1) | 16.3 (2.8) | 14.7 (3.8) | 16.9 (2.4) |

| MMSE, score 0–30 | 28.8 (1.4) | 29.0 (1.1) | 28.8 (1.0) | 28.1 (1.3) | 26.4 (2.1) |

| AMNART | 120.4 (9.6)* | 120.0 (9.6) | 122.5 (8.4)* | 117.5 (15.4) | 120.1 (7.7) |

| GDS, score 0–14 | 1.2 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.2) | 3.4 (2.9) | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Subjective, score 1–7 | 5.1 (1.0) | 5.3 (0.9) | 4.9 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| Objective, score 0–25 | 12.7 (4.3) | 13.5 (3.5) | 13.9 (3.0) | 8.4 (5.5) | 4.9 (4.6) |

All values (except gender) represent means ± standard deviation. Abbreviations: Aβ− = amyloid negative; Aβ+ = amyloid positive; AMNART = American National Adult Reading Test; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; y=years.

missing data for one person.

The healthy older adults were enrolled in the Harvard Aging Brain Study at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Dagley, et al., 2015). Participants were defined as cognitively normal if they had a mini-state mental exam (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, & McHough, 1975) score of 27–30 (inclusive with educational adjustment), and a global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Morris, 1993) score of 0.

The MCI patients were enrolled in an investigator-initiated study at the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment and the Massachusetts General Hospital. All patients met criteria for amnestic MCI (single or multiple domain) (Petersen, 2004), with an MMSE score of 24–30 (inclusive), a CDR global score of 0.5 (with memory box score of 0.5 or higher), essentially preserved instrumental ADL (as determined by a clinician) and no evidence of dementia. Of note, subjects with non-amnestic MCI were not eligible to participate in this study.

Exclusion criteria for all subjects were a history of neurologic or major psychiatric disorder, history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, contra-indications for MRI, use of medications that affect cognitive function, severe cardiovascular disease, alcohol or substance abuse, or known cerebrovascular disease (as determined by a the Modified Hachinski Ischemic score of 4 and higher (Rosen, Terry, Fuld, Katzman, & Peck, 1980) and/or presence of cortical infarct, or multiple lacunes, extensive leukoariosis on structural MRI. All subjects performed the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage, et al., 1983). Note that the healthy older adults had the long form (30 questions) of the GDS that was transformed to the short form (15 questions) to be comparable with the MCI patients, which had the short form (15 questions). Finally, an adjusted GDS score was calculated by removing 1 overlapping subjective memory complaint question (Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most?).

2.3 Estimate of awareness of memory functioning

An index of awareness of memory functioning was assessed by calculating discrepancy scores between objective memory scores (the delayed Logical memory test of the Wechsler Memory scale) (Wechsler, 1981) and a subjective memory scores (the “general frequency of forgetting” subscale of the Memory Functioning Questionnaire) (Gilewski, Zelinski, & Schaie, 1990). The 18 first questions of this subscale contains items regarding everyday situations in which a person would need to use his/her memory; each item rates the frequency with which the person would rate his/her memory in terms of the kind of problems they experience on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘major problems’) to 7 (‘no problem’). The scale was transformed to numbers ranging from 0 to 6. The Logical Memory IIa of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised is a standardized test that assesses delayed free recall of a short story, consisting of 25 units of information, approximately 20 minutes after it was presented. To investigate whether clinical subgroups with amyloid pathology have altered memory awareness, we computed a memory awareness measure using a normative group as reference. Thus, raw scores from objective and subjective measures were converted to z-scores for each subject, using the mean and SD from our CN individuals without Aβ pathology. A discrepancy score between the objective and subjective measures was then calculated, where a lower score indicates over-estimation of memory functioning (these individuals believe they are functioning at a higher level than their objective memory performance would suggest), 0 indicates normal awareness of memory functioning, and a higher score indicates underestimation of memory functioning (these individuals believe they are functioning less well than their objective performance would suggest).

2.4 PiB-PET acquisition and processing

Amyloid deposition was estimated with N-methyl-[11C]-2-(4-methylaminophenyl)-6-hydroxybenzothiazole (Pittsburg Compound B, PIB), prepared as described by Mathis, et al. (2002); (2003) and acquired at MGH, as previously described (Gomperts, et al., 2008; Johnson, et al., 2007; Rentz, et al., 2010), with a Siemens/CTI ECAT HR scanner. In short, following a transmission scan, 8.5–15 mCi 11C-PiB is injected intravenously as a bolus, followed by a 60-min dynamic PET scan in 3-D mode (63 image planes, 15.2 cm axial field of view, 5.6 mm transaxial resolution and 2.4 mm slice interval; 69 frames: 12 × 15s, 57 × 60s). PIB-PET data were processed with Statistical Parametric Mapping v8 using a protocol similar as described in Hedden, et al. (2012). PiB images were realigned, and the first 8 minutes of data were averaged and used to normalize data to the Montreal Neurological Institute FDG template and smoothed with a Guassian filter (8-mm FWHM). For each subject, PIB retention was expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR) at each voxel (Johnson, et al., 2007; Logan, et al., 1990; Price, et al., 2005), applying Logan’s graphical method (40- to 60 minute interval, using gray matter cerebellum as a reference region (Mormino, Betensky, Hedden, Schultz, Amariglio, et al., 2014).

Amyloid burden was estimated for each individual by extract a mean PiB value from an aggregate of cortical brain regions using the Harvard Oxford atlas that typically have elevated PiB burden in patients with AD. These regions included frontal, lateral temporal and parietal, and retrosplenial cortices. Individuals were classified as either being Aβ-positive (Aβ+) and Aβ-negative (Aβ−) using a as cutoff value of 1.20 as previously determined in the study by our group Mormino, Betensky, Hedden, Schultz, Ward, et al. (2014). Subjects where not informed of their amyloid status.

2.5 Statistical methods

All assumptions of linear modeling were met in the reported analyses. A set of GLM univariate analysis of variance was performed. First, we examined the effect of clinical group (CN, MCI) and amyloid as a continuous variable on awareness of memory function (dependent variable). Age, gender, education and GDS were used as covariates. Second, awareness of memory (dependent variable) was also compared across group (CN Aβ−, CN Aβ+, MCI Aβ−, MCI Aβ+) (fixed effects), controlling for age, gender, education and GDS. Post hoc contrasts were performed adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni method to compare level of self-awareness between the groups. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

In the whole sample, lower MMSE (r=0.19, p<0.001), lower GDS (r=0.12, p=0.05) and male gender (t=−3.2, p<0.002) were associated with over-estimation of memory functioning. There was no effect of age and education on memory self-awareness. In the CN, increased GDS (r=0.18, p=0.003) and female gender (t=−2.7, p<0.007) were associated with under-estimation of memory functioning. There was no effect of age, education and MMSE on self-awareness of memory function in the CN group. In the MCI patients, lower MMSE (r=0.54, p=0.001) was associated with overestimation of memory functioning. There was no effect of age, education, and GDS on self-awareness of memory function in the MCI group.

When comparing demographic variables across the preclinical and prodromal stages of CN and MCI, CN Aβ− individuals were slightly younger than CN Aβ+ (t=−2.7, df=260, p=0.007). Both MCI groups had lower MMSE score than the CN groups (MCI Aβ− compared to CN Aβ−: t=3.2, df=212, p=0.002; MCI Aβ− compared to CN Aβ+: t=2.5, df=76, p=0.016; MCI Aβ+ compared to CN Aβ−: t=9.1, df=217, p<0.001, and MCI Aβ+ compared to CN Aβ+: t=7.1, df=81, p<0.001). In addition, MCI Aβ+ patients had lower MMSE score than MCI Aβ− patients (t=2.7, df=33, p<0.01). MCI Aβ− patients had higher GDS score than MCI Aβ+ and both CN groups (MCI Aβ− compared to MCI Aβ+: t=3.6, df=33, p<0.001; MCI Aβ− compared to CN Aβ−: t=−6.4, df=212, p<0.001; MCI Aβ− compared to CN Aβ+: t=−5.5, df=76, p<0.001). There were fewer females in the MCI Aβ+ group as compared to both CN groups (MCI Aβ+ compared to CN Aβ−: χ2=4.6, df=1, p=0.032; MCI Aβ+ compared to CN Aβ+: χ2=5.0, df=1, p=0.025). No significant differences in years of education and AMNART were found across the groups.

3.2 Association of memory self-awareness and amyloid pathology

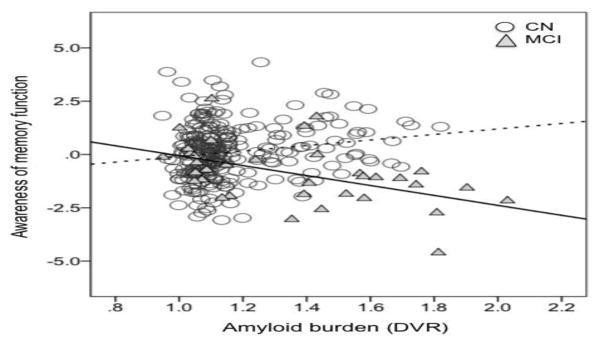

A univariate analysis of variance was conducted to examine the effect of clinical group (CN, MCI) and amyloid (as a continuous variable) on self-awareness of memory function. Age, gender, education and GDS was entered as covariates. A statistically significant interaction between clinical group and amyloid was found (F1, 289=11.2, p<0.001). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a significant positive correlation between memory self-awareness and amyloid in the CN group (r=0.2, p=0.006) such that underestimation of memory functioning was related to increased amyloid pathology. In contrast, a significant negative correlation was found in the MCI group (r=−0.5, p=0.002), such that over-estimation of memory functioning was related to increased amyloid pathology (Figure 1). The Fisher r-to-z transformation demonstrated a statistically difference between the two correlation coefficients (z=4.01, p<0.001).

Figure 1. Relationship between memory awareness and amyloid pathology in cognitively normal and MCI patients.

CN=Cognitively normal; MCI= mild cognitive impairment; Cognitively normal individuals demonstrate a positive relationship (r=0.2, p=0.006) between memory awareness and amyloid pathology (dotted line), whereas MCI patients demonstrate a negative relationship (r=−0.5, p=0.002) between memory awareness and amyloid pathology (bold line).

3.3 Comparison of memory self-awareness across Aβ groups in cognitively normal and MCI patients

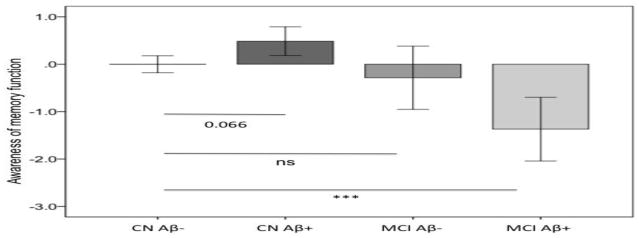

To investigate the relationship between self-awareness of memory function and groups, a univariate analysis of variance with memory self-awareness as dependent variable and group (CN Aβ−, CN Aβ+, MCI Aβ−, MCI Aβ+) as fixed effect was used (Figure 2). Age, gender, education and GDS were entered as covariates. There was a significant effect of group on memory self-awareness (F3,289=10.4, p<0.001). Post hoc contrasts across groups revealed trend level statistically differences between CN Aβ− and CN Aβ+ (p=0.066), a statistically significant difference between CN Aβ− and MCI Aβ+ (p<0.001), and between CN Aβ+ and MCI Aβ+ (p<0.001) and between CN Aβ+ and MCI Aβ− (p=0.041). Differences between CN Aβ− and MCI Aβ− (p=0.7) and between MCI Aβ− and MCI Aβ+ (p=0.8) were not significant. Of note, memory self-awareness MCI Aβ− (t=−0.9, p=0.3) was not significantly different from 0, indicating that this group had normal insight into their memory functions.

Figure 2. Comparison of self-awareness of memory across Aβ groups in cognitively normal and MCI patients.

CN=Cognitively normal; MCI= mild cognitive impairment; Aβ− = low amounts of amyloid; Aβ+ = high amount of amyloid. A PiB DVR threshold of 1.2 was used as cut-off in both groups. Cognitively normal individuals with high amounts of amyloid demonstrate increased self-awareness of memory (hypernosognosia) as compared to cognitively normal individuals without amyloid deposition. MCI patients with high amounts of amyloid demonstrate decreased self-awareness of memory (anosognosia) as compared to cognitively normal individuals without amyloid deposition. No difference in self-awareness of memory between cognitively normal individuals without amyloid burden and MCI individuals without amyloid deposition was found. Mean and 95% confidence interval. Analysis was controlled for age, gender, education and GDS. ***p<0.001.

3.4 Replication of analyses using a matched CN group

To investigate that our results were not due to unequal n sizes between our groups, we performed a set of analyses with a smaller CN group, created by case-matching the sample to the MCI group based on age, gender and education. The univariate analysis (controlling for GDS) examining the effect of clinical group (CN, MCI) and amyloid (continuous) on self-awareness of memory showed a significant interaction effect between group and amyloid (F1,65=5.38, p=0.024). Post hoc analysis demonstrated a positive association (although non-significant) between memory self-awareness and amyloid in the CN group (r=0.2, p=0.18) and a negative association in the MCI group (r=−0.5, p=0.002). The Fisher r-to-z transformation was statistically different between the two correlation coefficients (z=3.1, p=0.002). Similarly, the univariate analysis of variance (controlling for GDS) with memory self-awareness as dependent variable and group (CN Aβ−, CN Aβ+, MCI Aβ−, MCI Aβ+) demonstrated a significant effect of group on memory self-awareness (F3,65=8.8, p<0.001). Post hoc contrasts across groups revealed a trending statistically significance differences between CN Aβ− and CN Aβ+ (p<0.09), a significant difference between CN Aβ− and MCI Aβ+ (p<0.007), and between CN Aβ+ and MCI Aβ+ (p<0.001) and between CN Aβ+ and MCI Aβ− (p=0.049). Differences between CN Aβ− and MCI Aβ− (p=0.1) and between MCI Aβ− and MCI Aβ+ (p=0.35) were not significant. Memory self-awareness MCI Aβ− (t=−0.67, p=0.51) was not significantly different from 0, indicating that this group had insight into their memory functions.

4. DISCUSSION

Here, we observed two states of altered self-awareness of memory across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD. We show that CN individuals harboring amyloid pathology (CN Aβ+) demonstrated heightened memory self-awareness (hypernosognosia). In contrast, MCI Aβ+ patients demonstrated over-estimation of their memory functioning (anosognosia). These findings provide empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis that altered memory self-awareness in the preclinical and prodromal stages of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with amyloid pathology in brain regions that has been shown to exhibit substantial elevation of PiB retention in AD patients (Raji, et al., 2008) and which, interestingly, also overlaps with brain regions that have been implicated in self-referential processing (Johnson & Ries, 2010; Northoff & Bermpohl, 2004; Northoff, et al., 2006; Schmitz & Johnson, 2007). Further supporting this is our finding that MCI patients without amyloid pathology in these regions demonstrated close to full insight into their memory functions.

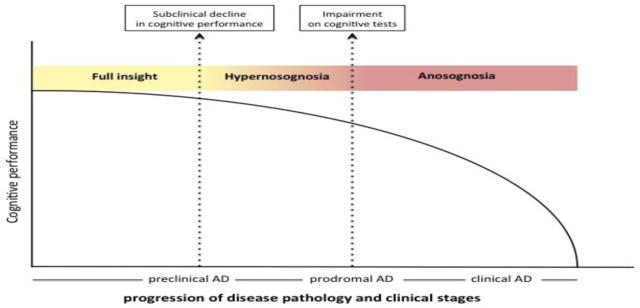

In an attempt to illustrate the current results we have created a hypothetical model of changes in self-awareness of memory function over the course of Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 3). In this model level of self-awareness varies in a continuum from normal awareness of cognitive performance to anosognosia through a phase termed hypernosognosia in which the individual experience heightened awareness of normal memory performance (see orange area in Figure 3). This model is similar to the cognitive model that Dalla Barba et al., (2015) recently proposed. In the model by Dalla Barba and collegues, they recognized a phase, termed cognitive dysgnosia, in which the individual experience awareness of normal performance as impaired. However, while the authors propose that CN individuals with cognitive dysgnosia may be less likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, our findings suggest that under-estimation of memory functioning is linked to amyloid pathology in the CN. Our findings are consistent with previous reports in individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline which have demonstrated that self-reports of memory impairment (but performing within normal limits on objective cognitive tasks) is linked to increased Aβ burden (Amariglio, et al., 2012; Perrotin, et al., 2012), metabolic dysregulation (Scheef, et al., 2012) as well as decreased cerebral volume, especially hippocampal volume (Jessen, et al., 2006; Palm, et al., 2013; Saykin, et al., 2006; Stewart, et al., 2008; Striepens, Scheef, et al., 2010; van Norden, et al., 2008; Wang, et al., 2006). In addition, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline have a higher incidence of prospective Alzheimer’s disease (Geerlings, Jonker, Bouter, & Schmand, 1999; Schmand, Jonker, Geerlings, & Lindeboom, 2009; van Harten, et al., 2013). However, one study found that Subjective Cognitive Decline did not predict cognitive decline in a community sample of older adults (Jorm, et al., 1997). Although one caveat in the study by Jorm et al., (1997) was that the sample may have included people with cognitive impairment who were unaware of any change, again speaking for the fact that the level of self-awareness of memory function may vary across Alzheimer’s disease. With this in mind, we believe that the term hypernosognosia (from Greek meaning hyper= over, excessive; nosos= disease; gnosis=knowledge) might better capture the perceived changes in memory that these individuals are experiencing.

Figure 3. A hypothetical model of awareness of memory across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD.

The model depicts cognitive performance (y-axis), awareness of memory function (color coded) and their relationship to disease pathology and clinical stages (x-axis) of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). After a phase of stable cognitive performance in the presence of increasing pathology, subtle decline of cognitive performance occurs at which point the individual becomes increasingly aware of a change in memory function (hypernosognosia: orange color). Of note, hypernosognosia might be present in individuals without increased neurodegenerative pathology which might represent the “worried well” population. As pathology increases and impairment of cognitive tests is documented clinically, the individuals self-report’s of memory impairment levels off and becomes less reliable (anosognosia; red color). Of note, we found that MCI patients without increased amyloid pathology had insight into their memory impairment. The model is based on cross-sectional data.

Despite an increasing number of studies that have suggested that individuals with Subjective Cognitive Decline may be in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. Amariglio, et al., 2015) but see also Jessen, Amariglio, et al. (2014)), it still remains a conundrum at what stage anosognosia occurs and if, in fact, an individual’s self-judgment of his/hers own cognitive abilities do change over the course of the disease as pathology increases (see red area in Figure. 3). With regard to MCI, there is evidence to show that the level of awareness do indeed vary (see Roberts, et al. (2009) for a systematic review), which have implications for the use of subjective cognitive decline in the setting of MCI. For instance, a recent longitudinal study by Wolfsgruber, et al. (2014) studied 417 MCI patients with and without memory concerns. They found that lower memory performance and Subjective Cognitive Decline independently increased the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, a significant interaction effect between the two was found such that Subjective Cognitive Decline was more predictive at early stages of MCI, while in more advanced stages of MCI it was not found to contribute to risk of dementia (Wolfsgruber, et al., 2014), most likely reflecting the onset of anosognosia and thus reduced validity of the self-reports of memory performance. With regard to the current findings, we found that individuals with MCI do indeed vary in regard to their self-awareness of memory function, such that MCI patients with high amyloid show decreased self-awareness of memory as compared to MCI patients with low amyloid. Longitudinal studies will determine whether loss of self-awareness in these individuals may serve as a relevant predictor of progression to Alzheimer dementia, as well as investigate whether the MCI patients with insight to their memory impairment will progress, remain stable or convert back to normal after follow-up.

Interestingly, with regard to demographics, we found a gender effect such that males had significantly decreased memory awareness as compared to females across the whole sample. To investigate this further and to determine if these findings are relevant in the context of amyloid deposition and risk for AD we performed a set of univariate analysis of variance (controlling for age, education, and GDS) with memory self-awareness as dependent variable and group (CN Aβ−, CN Aβ+, MCI Aβ−, MCI Aβ+) and gender (female, male) as fixed groups. This analysis did not yield a significant interaction effect of group and gender (F3,286=1.2, p=0.32). Similarly, just examining the CN and MCI groups separately did not reveal a significant interaction effect between groups Aβ−/Aβ+ and gender in the CN (F1,255=0.64, p=0.42) or MCI (F1,28=1.2, p=0.28). These results suggest that although there seems to be a general effect of gender on self-awareness of memory it does not seem to relate to amyloid burden or clinical group. However, future studies might examine other pathological markers such as neurodegenerative imaging markers, e.g. FDG and Tau PET, to determine whether gender might contribute to differential changes in self-awareness as individuals progress to AD dementia.

Some limitations of this work need to be acknowledged. To date, there is no consensus on how to optimally assess anosognosia in AD, but see discussion in Starkstein (2014). Here, we use a discrepancy score between the participant’s self-assessment and objective task performance, an approach that has been used in several previous publications investigating anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. Reis et al., (2011), 2012, Perrotin et al., (2015)). In addition, we are aware that the accuracy of reported concerns may be affected by confounding factors, for instance mood symptoms of the participant. Further complicating the picture is that depressive symptoms could represent early Alzheimer’s disease-related changes. With regard to anosognosia, previous studies have found increasing anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease to be associated with less severe depression (Starkstein, 2014), whereas studies on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease have found evidence of subthreshold symptoms of depression (Jessen, Amariglio, et al., 2014). To address this issue, although all of our participants were at subsyndromal levels, we controlled for depressive symptom in all our statistical models. Another limitation of this study is the fact that we had fewer MCI individuals as compared to CN. To ensure our results were not due to these unequal n sizes, we performed a set of sub-analyses using a smaller CN group matched to the MCI group using age, gender and education. Reassuringly, we found that our main results remained the same.

This is the first study to use in vivo amyloid imaging to assess the pathological substrates of altered memory self-awareness in clinically normal adults and MCI patients. Our results demonstrate “a flip” in the self-awareness of memory function that tracks with amyloid pathology across the preclinical and prodromal stages of AD. The findings of variability of awareness could have implications to the reliability of a person’s complaints of memory dysfunction. Discordant subjective and objective measures may provide an important piece of information to the clinician and should be considered in the diagnostic criteria of preclinical and prodromal AD.

Highlights.

Altered self-awareness of memory tracks with amyloid (Aβ) burden.

Normal adults harboring Aβ demonstrated heightened awareness (hypernosognosia).

MCI patients with increased Aβ pathology demonstrated anosognosia.

MCI patients with low Aβ burden have normal insight into their memory functions.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institute of Health under Award number K01AG048287 [PV], AG042228 [DML], K24 AG035007 [R.A.S.], R01 AG027435-S1 [R.A.S and K.A.J.], P01AG036694 [R.A.S. and K.A.J.], P50AG00513421 [R.A.S. and K.A.J.], and K24AG035007 [R.A.S.]. This research was carried out in whole or in part at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41EB015896, a P41 Regional Resource supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Beta amyloid

- CN

Clinically normal

- MCI

Mild Cognitive Impairment

- PiB

Pittsburgh Compound B

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: PV, RS, RA

Analysis and interpretation of data: PV, RS, RA, DML, BH

Drafting of the manuscript: PV

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: PV, RA, BH, KJ, JC, DML, AP-L, DR, RS

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. McLaren is currently a Biospective, Inc. employee; however, Biospective, Inc. did not contribute resources or have any involvement in this study. All other authors report no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnew SK, Morris RG. The heterogeneity of anosognosia for memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of the literature and a proposed model. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sullivan C, Maye J, Gidicsin C, Pepin LC, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Rentz DM. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amariglio RE, Mormino E, Pietras A, Marshall GA, Vannini P, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Subjective cognitive concerns, amyloid-B and neurodegeneration in clinically normal elderly. Neurology. 2015;85:1–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinski MJ. Contibution a l’etudedes troubles mantaux dans l’hemiplegie organique cerebrale (Anasognosie) Revue neurologique. 1914;12:845–848. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner R, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: Anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Krienen FM, Liu H, Hedden T, Andrews-Hanna JR, Sperling RA, Johnson KA. Cortical Hubs Revealed by Intrinsic Functional Connectivity: Mapping, Assessment of Stability, and Relation to Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1860–1873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5062-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Whitaker C, Nelis S. Appraisal of memory functioning and memory performance in healthy ageing and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2010;17:462–491. doi: 10.1080/13825580903581558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagley A, LaPoint M, Huijbers W, Hedden T, McLaren DG, Chatwal JP, Papp KV, Amariglio RE, Blacker D, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Schultz AP. Harvard Aging Brain Study: Dataset and accessibility. Neuroimage. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.069. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Barba G, La Corte V, Dubois B. For a cognitive model of subjective memory awareness. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease. 2015;48:S57–S61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison PM, Archer HAM, Hinz RP, Hammers AP, Pavese NM, Tai YFM, Hotton GM, Cutler DB, Fox NP, Kennedy AM, Rossor MMDD, Brooks DJMDD. Amyloid, hypometabolism, and cognition in Alzheimer disease: An [11C]PIB and [18F]FDG PET study. Neurology. 2007;68:501–508. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244749.20056.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Forsberg A, Almkvist O, Blomquist G, Larsson E, Savitcheva I, Wall A, Ringheim A, Langstrom B, Nordberg A. Two-year follow-up of amyloid deposition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006;129:2856–2866. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHough PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading cognit9ive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg A, Engler H, Almkvist O, Blomquist G, Hagman G, Wall A, Ringheim A, Långström B, Nordberg A. PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of aging. 2008;29:1456–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeone F, Pappalardo S, Chieffi S, Iavarone A, Carlomagno S. Anosognosia for memory deficit in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26:695–701. doi: 10.1002/gps.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerlings MI, Jonker C, Bouter LM, Schmand B. Association between memory complaints and incident Alzheimer’s disease in elderly people with normal baseline cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:531–537. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW. The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for Assessment of Memory Complaints in Adulthood and Old Age. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomperts SNMDP, Rentz DMP, Moran EB, Becker JAP, Locascio JJP, Klunk WEMDP, Mathis CAP, Elmaleh DRP, Shoup TP, Fischman AJM, Hyman BTMDP, Growdon JHM, Johnson KAM. Imaging amyloid deposition in Lewy body diseases SYMBOL. Neurology. 2008;71:903–910. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326146.60732.d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Mormino EC, Amariglio RE, Younger AP, Schultz AP, Becker JA, Buckner RL, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Rentz D. Cognitive profile of amyloid burden and white matter hyperintensities in cognitively normal older adults. J Cogn Neurosci. 2012;32:16233–16242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F. Subjective and objective cognitive decline at the pre-dementia stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:S3–S7. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0539-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, Dubois B, Dufouil C, Ellis KA, van der Flier WM, Glodzik L, van Harten AC, de Leon MJ, McHugh P, Mielke MM, Molinuevo JL, Mosconi L, Osorio RS, Perrotin A, Petersen RC, Rabin LA, Rami L, Reisberg B, Rentz DM, Sachdev PS, de la Sayette V, Saykin AJ, Scheltens P, Shulman MB, Slavin MJ, Sperling RA, Stewart R, Uspenskaya O, Vellas B, Visser PJ, Wagner M Group SCDISIW. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement. 2014;10:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Feyen L, Freymanna K, Tepest R, Maier W, Heunb R, Schild HH, Scheef L. Volume reduction of the entorhinal cortex in subjective memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1751–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, et al. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: Effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:414–422. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Wolfsgruber S, Wiese B, Bickel H, Mösch E, Kaduszkiewicz H, Pentzek M, Riedel-Heller SG, Luck T, Fuchs A, Weyerer S, Werle J, van den Bussche H, Scherer M, Maier W, Wagner M. AD dementia risk in late MCI, in early MCI, and in subjective memory impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, Smith EE, Rosand J, Rentz DM, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, DeKosky ST, Fischman AJ, Greenberg SM. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Annals of Neurology. 2007;62:229–234. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Ries ML. Functional Imaging of Self-Appraisal. In: Prigatano GP, editor. The Study of Anosognosia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Ger Psych. 2000;15:983–991. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<983::aid-gps238>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Mackinnon A. Do cognitive complaints either predict future cognitive decline or reflect past cognitive decline? A longitudinal study of an elderly community sample. Psychol Med. 1997;27:91–98. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbe E, Salmon E, Perani D, Holthoff V, Sorbi S, Elsner A. Anosognosia in very mild Alzheimer’s disease but not in mild cognitive impairment. Dem Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:349–356. doi: 10.1159/000084704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalbe E, Salmon E, Perani D, Holthoff V, Sorbi S, Elsner A, Weisenbach S, Brand M, Lenz O, Kessler J, Luedecke S, Ortelli P, Herholz K. Anosognosia in Very Mild Alzheimer’s Disease but Not in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:349–356. doi: 10.1159/000084704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen NMMDP, Aalto SM, Wilson IAP, Nagren KP, Helin SM, Bruck AMDP, Oikonen VM, Kailajarvi MMDP, Scheinin MMDP, Viitanen MMDP, Parkkola RMDP, Rinne JOMDP. Voxel-based analysis of PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1575–1580. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240117.55680.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang GF, Estrada S, Ausén B, Debnath ML, Barletta J, Price JC, Sandell J, Lopresti BJ, Wall A, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Annals of Neurology. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, Christman DR. Graphical Analysis of Reversible Radioligand Binding from Time-Activity Measurements Applied to [N−11C-methyl]-(−)-Cocaine PET Studies in Human Subjects. J Cereb blood flow metab. 1990;10:740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis CA, Bacskai BJ, Kajdasz ST, McLellan ME, Frosch MP, Hyman BT, Holt DP, Wang Y, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Klunk WE. A Lipophilic Thioflavin-T Derivative for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging of Amyloid in Brain. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2002;12:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis CA, Wang Y, Holt DP, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Klunk WE. Synthesis and Evaluation of 11C-Labeled 6-Substituted 2-Arylbenzothiazoles as Amyloid Imaging Agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;46:2740–2754. doi: 10.1021/jm030026b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn SM, Schacter DL. Unawareness of deficits in neuropsychological syndromes. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology. 1989;11:143–205. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, LaRossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: Potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino E, Betensky RA, Hedden T, Schultz AP, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA. Synergistic effect of β-amyloid and neurodegeneration on cognitive decline in clinically normal individuals. JAMA Neurology. 2014;71:1379–1385. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino E, Betensky RA, Hedden T, Schultz AP, Ward A, Huijbers W, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Sperling RA Initiative, t. A. s. D. N., ageing, t. A. I. B. a. L. f. s. o., & Study, t. H. A. B. Contributions of amyloid and APOE4 to cognitive and functional decline in aging. Neurology. 2014;82:1760–1767. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Bermpohl F. Cortical midline structures and the self. Trends Cogn Science. 2004;8:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain: a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage. 2006;31:440–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm WM, Ferrarini L, van der Flier WM, Westendorp RGJ, Bollen ELEM, Middelkoop HAM, Milles JR, van der Grond J, van Buchem MA. Cerebral Atrophy in Elderly With Subjective Memory Complaints. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jmri.23977. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotin A, Mormino EC, Madison CM, Hayenga AO, Jagust WJ. Subjective Cognition and Amyloid Deposition Imaging A Pittsburgh Compound B Positron Emission Tomography Study in Normal Elderly Individuals. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:223–229. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Lu X, Hoge JA, Ziolko SK, Holt DP, Meltzer CC, DeKosky ST, Mathis CA. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb blood flow metab. 2005;25:1528–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigatano GP. The study of anosognosia. Oxford: Pxford university press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raji C, Becker J, Tsopelas N, Price J, Mathis C, Saxton J, Lopresti B, Hoge J, Ziolko S, DeKosky ST, Klunk W. Characterizing regional correlation, laterality and symmetry of amyloid deposition in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound B. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;172:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: Relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology. 1993;15:231–244. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentz DM, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, Moran EK, Eng E, Buckner RL, Sperling RA, Johnson KA. Cognition, reserve, and amyloid deposition in normal aging. Annals of Neurology. 2010;67:353–364. doi: 10.1002/ana.21904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JL, Clare L, Woods RT. Subjective memory complaints and awareness of memory functioning in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dem Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28:95–109. doi: 10.1159/000234911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ. Anosognosia in neurodegenerative disease. Neurocase: the neural basis of cognition. 2011;17:231–241. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2010.522588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Terry RD, Fuld PA, Katzman R, Peck A. Pathological verification of ischemic score in differentiation of dementias. Annals Neurol. 1980;7:486–488. doi: 10.1002/ana.410070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, McHugh TL, Mamourian AC. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67:834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheef L, Spottke A, Daerr M, Joe A, Striepens N, Kolsch H, Popp J, Daamen M, Gorris D, Heneka MT, Boecker H, Biersack HJ, Maier W, Schild HH, Wagner M, Jessen F. Glucose metabolism, gray matter structure, amd memory decline in subjective memory impairment. Neurology. 2012;79:1332–1339. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826c1a8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmand B, Jonker C, Geerlings M, Lindeboom J. Subjective memory complaints in the elderly: depressive symptoms and future dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;171:373–376. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz TW, Johnson SC. Relevance to self: A brief review and framework of neural systems underlying appraisal. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2007;31:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan A, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Jr, Kaye JA, Montine TJ, Park D, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster M, Phelphs CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: Diagnosis, frequency, mechanism and clinical correlates. Cortex. 2014;61:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, Power BD. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: Neuroimaging correlates. In: Prigatano GP, editor. The Study of Annosognosia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 171–187. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Dufouil C, Godin O, Ritchie K, Maillard P, Delcroix N, Crivello F, Mazoyer B, Tzourio C. Neuroimaging correlates of subjective memory deficits in a community population. Neurology. 2008;70:1601–1607. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310982.99438.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepens N, Scheef L, Wind A, Popp J, Spottke A, Cooper-Mahkorn D, Suliman H, Wagner M, Schild HH, Jessen F. Volume Loss of the Medial Temporal Lobe Structures in Subjective Memory Impairment. Dem Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000264630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepens N, Spottke A, Scheef L, Wind A, Popp J, Cooper-Mahkorn D, Sulimana H, Schild HH, Jessen F. Volume loss in of the medial temporal lobe structures in subjective memory impairment. Dem Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000264630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabert MH, Albert SM, Borukhova-Milov L, Camacho Y, Pelton G, Liu X, Stern Y, Devanand DP. Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: Prediction of AD. Neurology. 2002;58:758–764. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Flier WM, van Buchem MA, Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Mutsaers ER, Bollen ELEM, Admiraal-Behloul F, Westendorp RGJ, Middelkoop HAM. Memory complaints in patients with normal cognition are associated with smaller hippocamal volumes. J Neurol. 2004;251:671–675. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Harten AC, Visser PJ, Pijnenburg YAL, Teunissen CE, Blankenstein MA, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is the best predictor of clinical progression in patients with subjective complaints. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Norden AGW, Fick WF, de Laat KF, van Uden IWH, an Oudheusden LJB, Tendolkar I, Zwiers MP, de Leeuw FE. Subjective cognitive failures and hippocampal volume in elderly with white matter lesions. Neurology. 2008;71:1152–1159. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327564.44819.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PJ, Saykin AJ, Flashman LA, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, McHugh TL, MacDonald JW, Mamourian AC. Regionally specific atrophy of the corpus callosum in AD, MCI and cognitive complaints. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale - revised manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corp; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- West RL, Dennehy-Basile D, Norris MP. Memory self-evaluation: The effects of age and experience. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. 1996;3:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsgruber S, Wagner M, Schmidtke K, Frölich L, Kurz A, Schulz S, Hampel H, Heuser I, Peters O, Reischies FM, Jahn H, Luckhaus C, Hüll M, Gertz HJ, Schröder J, Pantel J, Rienhoff O, Rüther E, Henn F, Wiltfang J, Maier W, Kornhuber J, Jessen F. Memory Concerns, Memory Performance and Risk of Dementia in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink T, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale. Psych Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]