Abstract

Broadband spectroscopy is an invaluable tool for measuring multiple gas-phase species simultaneously. In this work we review basic techniques, implementations, and current applications for broadband spectroscopy. We discuss components of broad-band spectroscopy including light sources, absorption cells, and detection methods and then discuss specific combinations of these components in commonly-used techniques. We finish this review by discussing potential future advances in techniques and applications of broad-band spectroscopy.

Molecular spectroscopy has been shown to be a powerful analytical tool with a wide range of applications. The invention of the spectrograph by Fraunhofer in 1814 [1] led to the first broad bandwidth and high-resolution (at the time) studies of the spectra of atoms and molecules [2]. For many years, dispersive spectrometers (and later Fourier Transform spectrometers) continued to be the primary measurement technique due to the lack of high spectral brightness light sources. With the advent of lasers, in particular continuous-wave (cw) lasers, the focus shifted from broad bandwidth to high sensitivity and resolution. More recently, there has been renewed effort to develop systems that can provide the sensitivity and resolution of cw laser-based techniques over a broad spectral bandwidth. Here, we discuss some of the recent developments and hopefully give some insight into future directions the field may take. Because the general field of broadband spectroscopy is so broad, we limit this review to gas-phase transmission spectroscopy techniques using active light sources where sensitivity, bandwidth, spectral resolution, and accuracy are all important. We consider tunable laser sources to be outside the scope of this work.

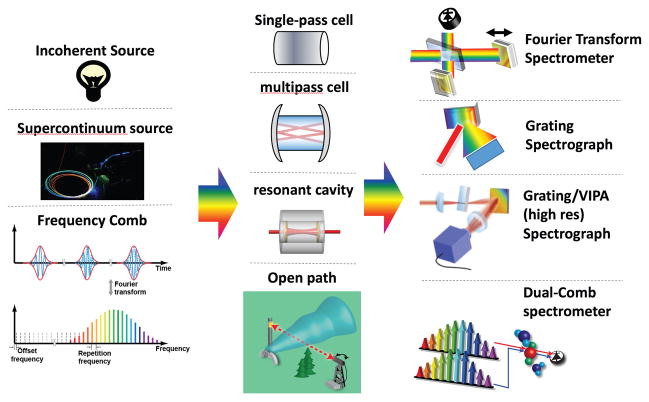

There are several primary motivations for using broadband spectroscopy as an analytical tool. First and foremost, a large spectral bandwidth allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple species. This enables a single instrument to serve many purposes and also provides a more complete understanding of complex processes. In addition, broad bandwidth enables accurate measurements in complex systems, where interfering absorption from unexpected features can cause significant errors for measurements with a limited spectral bandwidth. However, there are also significant challenges involved with developing sources and detection techniques that can provide the necessary resolution and sensitivity while operating over a wide bandwidth. Figure 1 summarizes the type of broadband source and detection approaches that are considered here. These have been combined in different ways to yield the long list of broadband spectroscopy techniques in Table 1 and discussed in this review.

Fig. 1.

Overview of broadband spectroscopy systems. Left column: broad-band light sources. Middle column: absorption cells. Right column: broad-band detectors.

Table 1.

List of acronyms for techniques discussed in this paper.

| Acronym | Definition | Section |

|---|---|---|

| BB-CRDS | Broad-Band Cavity Ring Down Spectroscopy | 3.D |

| CE-DOAS | Cavity-Enhanced Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy | 3.B |

| CE-DFCS | Cavity-Enhanced Direct Frequency Comb Spectroscopy | 3.E |

| DCS | Dual Frequency Comb Spectroscopy | 3.F |

| DOAS | Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy | 3.B, 3.C |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | 3.A |

| FTS | Fourier Transform Spectroscopy | 3.A |

| IBB-CES | Incoherent Broad Band Cavity-Enhanced Spectroscopy | 3.B |

| LP-DOAS | Long-Path Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy | 3.C |

| ML-CEAS | Mode-Locked Cavity Enhanced Absorption Spectroscopy | 3.E |

| THz-TDS | Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy | 3.G |

| TRFCS | Time-Resolved Frequency Comb Spectroscopy | 3.E |

Because these are all absorption spectroscopy techniques at some level, quantification of trace gases relies on Lambert-Beer’s law convolved with the instrument line shape (ILS):

| (1) |

where ν is an optical frequency, wavelength, or wavenumber, I0 is the initial intensity, L is the path length, and k are the different absorbers with absorption cross section σk(ν) (cm2/molecule) and number density Nk (molecules/cm3). For resolved molecular transitions, the cross section can be written as σ(ν) = ΣnSng(ν − ν0n), where the sum is over all n lines, Sn is the linestrength, and g(ν − ν0n) is the area-normalized lineshape function for a line with center frequency ν0n (see Tennyson et al. [3] for recommended lineshape functions). Finally, the number density is often converted to a volume mixing ratio, which gives the mole fraction of the measured species within the sample, and is then expressed typically as part-per-million by volume (ppmv), part-per billion by volume (ppbv), or part-per-trillion by volume (pptv).

The rest of the review is organized as follows. Section 1 provides an introduction to different applications of broadband spectroscopy and their associated requirements. In Section 2, we summarize the different sources, transmission geometries, detection systems used for broadband spectroscopy. Section 3 covers current systems and their applications. Finally, in Section 4 we discuss some of the future directions and applications of broadband spectroscopy.

1. APPLICATIONS

1.A. Atmospheric

Atmospheric measurements are made to monitor air quality and track changes in concentrations of pollutants over timescales of hours to decades. A selection of the important tropospheric species and their corresponding concentration is given in Table 2. Different broad-band techniques are better suited to measuring different classes of trace gases, see Table 2 in [4]. It is often desirable to measure multiple species simultaneously in order to correlate the changes in concentrations of different species to identify sources, such as identifying whether methane emissions are the result of oil and natural gas drilling (in which case it correlates strongly with ethane [5]) or from bovine feed lots (in which case it often correlates with ammonia [6]). Broadband spectroscopy is an obvious method for this task. In principle, it can provide real-time, in situ measurements of multiple gas species. The challenge though is to measure all of the desired species with high enough sensitivity and accuracy in the presence of time-varying absorption from other species (including aerosols), and to make these measurements in the field.

Table 2.

Example trace species in the boundary layer (lowest part of the troposphere). Greenhouse gases are significant contributors to climate change. Biogenic species are emitted from plants while anthropogenic species are emitted from human activities, and these react in the atmosphere with e.g. OH and O3 to form oxidation products. Halogen oxides are often found in the marine boundary layer from e.g. seaweed, and ozone-depleting species contribute to the Antarctic ozone hole. From [23–26].

| Compound | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Greenhouse Gases | |

| CH4 | 1.7 ppmv |

| N2O | 300 ppbv |

| SF6 | 4 pptv |

| Biogenic Species | |

| Terpenes (e.g. α-pinene) | 0.03–2 ppbv |

| Isoprene | 0.6–2.5 ppbv |

| Anthropogenic Species | |

| Alkanes | 1–300 ppbv |

| Alkenes/Alkynes | 0.01–10 ppbv |

| Aromatics | 0.01–3 ppbv |

| H2S | 0–800 pptv |

| NH3 | 0.02–100 ppbv |

| Oxidation Products | |

| HCHO | 0.1–60 ppbv |

| Acetone | 0.2–9 ppbv |

| Glyoxal (CHOCHO) | 0.01–1 ppbv |

| NO2 | 0.01–2000 ppbv |

| NO3 | 1–500 ppbv |

| N2O5 | < 15 ppbv |

| Nitric Acid | 0.1–50 ppbv |

| SO2 | 0.01–10 ppbv |

| CO | 200 ppbv |

| Halogen Oxides | |

| BrO | 0.1–10 pptv |

| IO | 0.1–2 pptv |

| Ozone-Depleting Species | |

| CFCl3 | 268 pptv |

| CF2Cl3 | 533 pptv |

| CH3Cl | 500 pptv |

| Other halocarbon species | 10–100 pptv |

Atmospheric gas sensing can be accomplished by point sensors that use a gas sampling cell or open-path sensors that use a long air path terminated by the detection system or a retroreflector (in principle, back scatter from a surface could be used, but the sensitivity is too low for broadband systems).

Point sensor measurements have been made with IBB-CES and CE-DOAS (Section 3.B) as well as BB-CRDS (Section 3.D). Point sensor techniques are well-suited to mobile platforms (e.g. aircraft) and can be used to measure the source strength of a particular area by driving or flying around the area (e.g. [7–10]).

Open-path measurements average over small-scale turbulent eddies and thus are more representative of the atmospheric composition in an area. In addition, open-path measurements avoid biases due to reactions or losses during sample handling. Historically, open-path measurements have been performed with FTIR (Section 3.A) and with LP-DOAS (Section 3.C); however, these systems have limited path length because of the spatial incoherence of the sources. More recently, quantitative long open-path greenhouse gas measurements have been demonstrated using dual frequency comb spectroscopy (DCS, Section 3.F) over paths of 2 km round trip.

In addition to trace gas detection, isotopic ratios can provide useful data. For example, the CO2 isotope ratio can track sources of pollution and help identify sources and sinks in the global carbon cycle. Methane isotope ratios can distinguish between anthropogenic and biogenic sources and can provide information about the source of methane in the crust (e.g. microbial vs thermogenic) [11] or in the atmosphere (e.g. fossil fuel vs. biogenic) [12]. Water isotope ratios can track water through the atmosphere, including dehydration methods of water moving from the tropical tropopause to the stratosphere [13] and movement of water through the hydrologic cycle [14, 15]. Comparison of water and CO2 isotopes between Mars and Earth provides information about gas transfer processes to the Martian atmosphere [16]. Currently, most isotope ratio measurements are performed using mass spectrometry or cw-laser spectroscopy to obtain high sensitivity; however, the ability to measure multiple isotope ratios simultaneously in the field could be a useful application of broadband spectroscopy.

For modeling, it is often not the concentration but rather the flux that is the quantity of interest. The technique of eddy covariance flux measures air-surface exchange of gases [17–21] by correlating the changes in the vertical wind velocity and the concentration of a particular species to determine if the surface is a source or sink of the gas. The measurements need to be at least several Hz in order to capture the small eddies that carry the trace gas in or out of the surface. Because of this requirement, it has only recently been done with broadband spectroscopy when Coburn et al. used a CE-DOAS system (Section 3.B) to measure the fluxes of glyoxal and NO2 between the ocean and the marine boundary layer [21].

Finally, in addition to the trace gases, the atmosphere includes atmospheric aerosols which are tiny liquid or solid particles suspended in the air. Those with diameters of few microns or smaller are most important for atmospheric chemistry. Sources are both natural (e.g. sea spray produces NaCl aerosols) and anthropogenic (e.g. combustion processes produce soot aerosols). Aerosols both scatter and absorb sunlight with spectra that depend on size and chemical composition. A basic understanding of their scattering and absorption cross sections is needed to accurately model their impact on the climate. Washenfelder et al. used IBB-CES (Section 3.B) to measure the scattering of several different model aerosols including those generated from solutions of ammonium sulfate, fulvic acid, and nygrosin dye [22].

1.B. Chemical Kinetics

Laboratory measurements of kinetics are important to support a variety of fields from atmospheric chemistry [27–29] to combustion [30–34] to fundamental chemistry. These processes are typically complex, with a large number of possible pathways and reactive intermediates that are potentially important drivers of further chemistry. In order to obtain accurate branching ratios for the different paths, the reactants, intermediates, and products all need to be measured. Thus, broadband spectroscopy is an attractive tool if the required bandwidth, sensitivity, and time resolution can be obtained. Example reactions include isoprene chemistry, peroxy radical reactions, ozonolysis of alkenes, and OH radical reactions.

Isoprene is one of the most abundant biogenic VOCs [25]; therefore understanding its reactions and products are important because even species with a small yield from isoprene will be abundant. While the oxidation of isoprene with OH is one of the most well-studied atmospheric reactions (e.g. [35] and references therein), this multi-generation reaction is complex and the chemistry changes with temperature and pollution conditions, leading to unexpected results [36]. Recently, broadband spectroscopy techniques (FTIR and CE-DOAS) were used to measure the first and second generation products from the reaction of isoprene + OH under high NOx and low NOx conditions [37].

Organic peroxy radicals (R–O–O•) are important intermediates in atmsopheric and combution reactions and can react with HO2 to form three different products: organic hydroperoxides (ROOH), alcohols (ROH) and alkoxy radicals (R–O•). The rates and branching ratios for each of these reactions determines the ultimate product distribution for this reaction and these values have been determined using FTIR [38, 39].

The reaction of alkenes with O3 to form stabilized Criegee intermediates was predicted over 50 years ago, but was finally detected by time-resolved FTS only very recently [40] (see Section 3.A).

In order to observe reactive intermediates, high time resolution (on the order of microseconds) is often required. Two broadband techniques have been demonstrated with microsecond time resolution: step-scanned FTS (Section 3.A) and time-resolved frequency comb spectroscopy (TRFCS, Section 3.E). The TRFCS system was used to track the photodissociation of deuterated acrylic acid to form trans-DOCO with 25 μs time resolution [41] and to measure the trans-DOCO radical formed from OD+CO [42].

1.C. Breath Analysis

Human breath contains hundreds to thousands of different compounds in a wide range of concentrations from a few percent for H2O to parts-per-quadrillion for many volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Some of the most prevalent species are given in Table 3. While many of the molecules in breath are byproducts from daily metabolism, some potentially arise (or change in abundance) due to diseases. The potential use of these molecules as markers for diseases is currently an active area of research, see, e.g. [43–51] for some reviews; however, as highlighted in many of these reviews, there are number of complications such as the lack standardized breath collection procedures and natural variability that cause significant challenges for reliable disease detection. As a result there are currently only a few FDA approved breath tests. Research in medical breath analysis can be divided into two primary directions: detection of a single or a few small species, and detection of many VOCs simultaneously.

Table 3.

| Compound | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Methane | 1–100 ppmv |

| CO | 1–5 ppmv |

| Acetone | 0.3–2.5 ppmv |

| N2O | 0.3–1.6 ppmv |

| Ammonia | 0.1–1 ppmv |

| Methanol | ~500 ppbv |

| Isoprene | 30–300 ppbv |

| NO | 1–80 ppbv |

| 2,3–Butanedione | 1–200 ppbv |

| Ethane | 2–20 ppbv |

| Other VOCs | 0.1–40 ppbv |

All current FDA-approved breath tests rely on small molecules: NO for asthma, CO for neonatal jaundice, and methane for gastrointestinal issues [51, 55]. Other small molecules are current topics of investigation as potential tracers for diseases, including (see also [48]): NO, CO, CO2, and N2O [52] or ethane [56] for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acetone for diabetes [57–59], ethane for lung cancer [60], and NH3 (and possibly methylamines) for kidney function [61, 62]. As in atmospheric chemistry, isotopic ratios can also provide unique information. For example, a change in the abundance of δ13CO2 can be detected after the ingestion of 13C-labeled substances [51]. Currently, a breath test for gastric infection by Helicobacter pylori using 13C-labeled urea is FDA approved with future potential for monitoring liver metabolism [63] and acute liver disease [64].

Unlike for the small molecules, the origin of many of the VOCs in breath is unknown, thus studies tend to look at a large number of VOCs. A number of studies have found tentative correlations between a selected subset of VOCs and diseases [50] such as tuberculosis [65], cancer (see [66, 67] and references therein), and COPD [68]. To date though, no studies have demonstrated robust enough results to provide a clinically useful test.

Despite the potential, breath analysis using broadband spectroscopy has only been preliminarily demonstrated a few times using FTIR (Section 3.A) and near-IR CE-DFCS (Section 3.E). This is at least partially due to the required combination of real-time results, high sensitivity in a low sample volume, and high selectivity against a complex and cluttered spectral background.

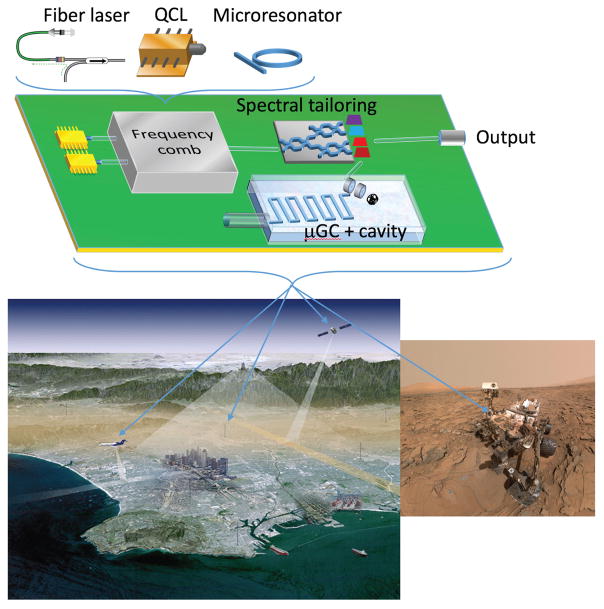

1.D. Astrochemistry

The atmospheric composition and chemistry of solar system planets [69] and moons [70, 71] is of interest for understanding planetary formation and can be used to track planetary geophysical processes (e.g., see [72–75]). While it is possible to study these atmospheres using earth-based telescopes, more precise information can often be obtained with in situ measurements [76]. Isotopic measurements of CO2 and H2O on Mars [16, 77] show large enrichment of δ18O for both gases as well as enrichment of δ13C (which are defined as , where X′ is the tracer isotope (13C or 18O) and X is the standard isotope (12C or 16O) and the reference sample is Peedee belemnite for 13C and Standard Mean Ocean Water for 18O). This, combined with isotope ratio measurements from meteorites, provides evidence for atmospheric loss and ongoing volcanic activity. Active broadband spectroscopy could provide new information on future missions to Mars or other planets, if the system can be made small and compact while maintaining high sensitivity.

Broadband spectroscopy is also important for earth-based observational astronomy. Despite being cold, dilute, and primarily composed of atomic ions, the interstellar medium (ISM) contains a large number of molecules as well, including complex organic molecules [29, 78–81]. Its exact composition is still unknown, as evidenced by a collection of broad bands, collectively called the diffuse interstellar bands [82]. While these have been seen in observational data since the 1920s, only H2CCC and have conclusively been identified as the source of a few of the diffuse interstellar bands [83, 84]. The challenge for laboratory experiments is to replicate conditions in the ISM (i.e. temperature, pressure and concentrations) while maintaining high sensitivity for a wide range of potential molecules. Such laboratory-based studies can both provide reference spectra to support observations and a better understanding of the kinetics of reactions at low temperatures [85–87] to support models of chemical reactions in the ISM. In addition to the ISM, the dense gas and dust that forms stars, and the disks around young stars, are so opaque/cold that only THz and longer wavelength photons can penetrate them. Thus, laboratory THz spectroscopy is necessary to support observations from new observatories such as the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astonomy (SOFIA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

1.E. Industrial applications

In industrial processes, gases must be monitored for purity to avoid contamination for health and/or environmental purposes. Arsine gas (AsH3) is used in the production of semiconductors. Impurities in the gas at the 10–100 ppbv level can result in lattice structure defects from unintentional doping and currently a combination of different instruments are used to measure all important impurities [88–91]. Reducing this monitoring function to a single broadband system will require a technique with high sensitivity even in the presence of extremely strong absorption from the carrier gas. In a first effort towards this, a CE-DFCS system was developed to measure trace quantities of water in arsine [92].

The combustion of hydrocarbons is an extremely complicated process. Improving the efficiency of combustion systems while simultaneously reducing the emissions of pollutants such as CO, NOx, and unburned hydrocarbons requires an interplay between laboratory-based kinetics measurements (Section 1.B), modeling, and in situ measurements [30–33]. These measurements often must deal with high temperatures and turbulent, fast-flow conditions while maintaining high sensitivity. A step towards rapid, broadband in situ measurements was recently demonstrated using DCS [93].

Broadband spectroscopy also has significant potential for helping industry report emissions of regulated gases and helping regulators monitor and verify the emissions reporting. These emissions include potential health hazards (e.g., VOCs such as benzene, toluene, etc.), clorinated hydrocarbons (CFCs and HCFCs) that deplete stratospheric ozone, and strong greenhouse gases such as CH4, N2O, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), per fluorocarbons (PFCs, from semiconductor manufacturing), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). Such measurements have sometimes been performed using FTIR (Section 3.A); however, to measure emissions after abatement systems are in place typically requires higher sensitivity than FTIR can provide.

1.F. Fundamental laboratory spectroscopy

All of these applications – and indeed any other applications of spectroscopy, broadband or otherwise – rely on having accurate line parameters or cross sections that can be scaled to the measurement conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure, other species present) for use in the Beer-Lambert equation (Equation 1). Only with accurate spectral models can complicated spectra be fit to accurately identify weak absorption from a trace species in the presence of strong absorption from other species (e.g., water in the atmosphere or in breath, trace contaminants in high-purity gases). For these measurements, the instrument lineshape (ILS) causes additional complications for determining the cross section or line parameters and thus needs to be known precisely.

Spectral databases such as those listed in Table 4 exist and contain a truly vast collection of spectral information. The gas-phase spectral information has been provided over decades of careful measurements typically with FTIR or grating spectrometers using an incoherent light source. As broadband techniques continue to develop and improve in resolution, sensitivity, and coverage, there is both a need and an opportunity to continue to improve these databases. For example, most of the databases have been developed for standard atmospheric conditions on Earth (with the notable exception of HITEMP [95]), and thus are not accurate for the temperature conditions encountered in combustion systems and on other planets. Frequency combs in particular might be well suited to providing additional high-resolution data beyond those available from FTS because of the inherent combination of high resolution and absolute frequency accuracy. In particular, systems that resolve individual comb modes can have a spectral accuracy at the kHz level (3 × 10−8 cm−1) with no instrument line shape contribution [103–105].

Table 4.

List of databases useful for high-resolution broad-band spectroscopy.

| Database | Wavelength Region | Data Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HITRAN and HITEMP | UV to THz | Line parameters | [94, 95] |

| MPI UV/Vis Spectral Database | UV to near IR | Measured cross sections | [96] |

| NIST Quantitative Infrared | IR | Measured cross sections | [97] |

| PNNL Northwest Infrared Database | near IR to far IR | Measured cross sections | [98] |

| Cologne Database for Molecular Spectroscopy | far IR and THz | Line parameters | [99, 100] |

| JPL Molecular Spectroscopy Database | sub-millimeter to microwave | Line parameters | [101] |

| GEISA | UV to THz | Line parameters | [102] |

The THz region is also of interest for fundamental laboratory studies because it contains information about intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding dynamics [106, 107], which is critical for a complete understanding of liquid water and solvation dynamics [108]. One of the primary challenges in studying the THz region so far has been the lack of good sources and detectors, although new broadband sources have recently been developed (see Section 3.G).

2. TECHNIQUES

Given the array of possible sources and detection methods, many broadband techniques exist. No one technique is best in all cases, and there is always a complicated tradeoff between system parameters that include: system complexity, spectral coverage (bandwidth and center frequency), frequency resolution, frequency accuracy, and sensitivity at both short times and long times. Sensitivity is often highlighted, however broadband systems will never attain the sensitivity of a single-frequency cw laser system and indeed the whole point is to achieve sufficient sensitivity but across a wide spectrum at high frequency resolution and/or accuracy. In that sense, quantitative comparisons between system sensitivities operating for different purposes and in different spectral regions should be regarded with caution.

2.A. Spectral bands and Sources

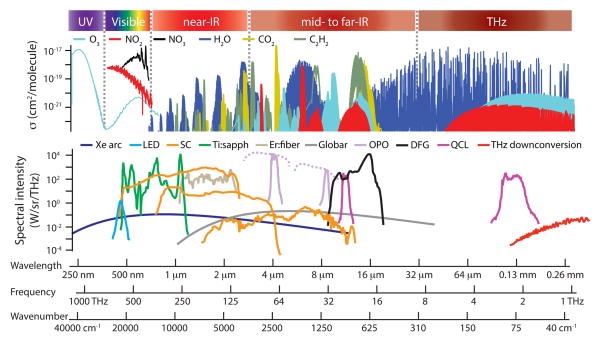

Figure 2 displays the regions of the electromagnetic spectrum of interest to molecular spectroscopy, along with available broadband sources. In general, the molecular absorption signals are stronger and richer in the mid-IR and THz and in the UV to visible, but sources and detectors are best developed in the visible and near-IR.

Fig. 2.

Example molecular cross sections and available sources in different spectral regions. For the laser based sources, we assume a 1 mrad divergence. For tunable sources, the tuning range is given by dashed lines. Cross-section data: [95] (NIR to THz), [148] (UV/Vis O3), [149] (vis NO2), [150] (vis NO3). Spectral source data: Xe arc lamp (blackbody at 6000 K, ε = 0.4, 450 W total power), blue LED (5W blue LedEngin LZ1-00B205), visible supercontinuum (estimate), Ti:sapphire comb with nonlinear fiber ([151]), Er:fiber comb with nonlinear fiber ([152]), near-IR supercontinuum ([120]), mid-IR supercontinuum ([122]), globar thermal source (blackbody at 1000 K, ε = 0.8, 140 W total power), periodically-poled litium niobate (PPLN) optical parametric oscillator (OPO) frequency comb ([141]), gallium phosphide (GaP) OPO comb ([142]), difference-frequency generation (DFG) ([146]), QCL frequency comb (two different sources, [153]), THz downconversion ([154]).

In addition to spectral coverage, sources differ in their spatial coherence, frequency coherence, spectral flatness, cost, size, relative intensity noise (RIN), and so on. Below we summarize these differences for the three important classes of sources.

2.A.1. Incoherent Broadband Sources: lamps, LEDs, Globars

The most readily available thermal light source is sunlight and many systems for atmospheric measurements use scattered or direct sunlight including DOAS, satellite-based spectrometers (e.g. the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 [109] and the Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment-FTS [110]), and ground-based FTS (e.g. the Total Carbon Column Observing Network [111, 112] and mobile FTS instruments, e.g. [113]). These systems have been used extensively; however, for obvious reasons they are limited to daytime operation during clear days and are less flexible in terms of measurement path and configuration. For this review, we limit the discussion to active sources.

Broadband spatially incoherent light sources include Xe-arc lamps, deuterium arc lamps (D-arc lamps), tungsten filament lamps, Globar, discharge lamps, or light-emitting diodes (LED) [24]. These sources have the advantage of simplicity and a broad spectrum, but the disadvantage of limited power per frequency and per spatial mode (i.e., high divergence). Blackbody sources such as globars and arc lamps cover the widest wavelength region but require significant power and often have an unstable spectrum (especially for arc lamps). LEDs can provide higher brightness, require significantly lower power, and have a stable spectrum but have a narrower spectrum and are only available in select wavelength regions (mostly in the visible to near-IR).

2.A.2. Supercontinuum

Supercontinuum sources are typically based on a high-power nanosecond- or picosecond-pulsed laser (e.g. Ti:sapphire or Er- or Yb-based lasers), which is amplified and injected into nonlinear optical fiber to create a supercontinuum of light [114–117]. There are a number of different supercontinuum sources (several of which are commercially available) in the visible and near infrared, which are summarized in Ref. [115, 118, 119], and recent work extends them to the UV and across the mid-infrared [115, 120–124]. Supercontinuum sources have a spectral brightness far in excess of the non-laser-based sources and, moreover, have a spatially coherent output that can support long interaction paths in a cavity or open-path configuration. However, it has been known for a while that they can be substantially noisier than an incoherent source due to technical noise amplification and fundamental limitations from the nonlinear broadening (see, e.g., [116, 125–129]). In particular, the spectrum can vary in shape so that the noise within a narrow spectral bin far exceeds the noise integrated across the spectrum. While the noise does depend on fiber and laser parameters, typically values are ~0.1% to 2% noise in a one second time window for a 0.1 nm bin, see, e.g. [130, 131], with significantly larger shot-to-shot fluctuations [132, 133]. In comparison, a thermal source will have a RIN ~1/bandwidth [134, 135], which corresponds to < 0.01% in a 0.1 nm bin in one second for many thermal sources. Neverthless, supercontinuum sources are an important new tool and have been used in a number of broadband spectrometers discussed later [130, 136–139].

2.A.3. Frequency comb

A frequency comb can be loosely defined as a laser source that produces a spectrum of equally-spaced, phase-coherent lines (or “teeth”) at well-defined and controllable frequencies (see e.g. [140]). Most frequency combs are generated from mode-locked lasers, which emit a series of ultrashort (⪷1 ps) pulses at a well-defined repetition rate (typically 100 MHz to 10 GHz). The repetition rate sets the spacing between the teeth in the frequency domain. New, less traditional comb sources that do not necessarily produce pulses (for example, mode-locked quantum cascade lasers, modulator-based combs, and microresonators) are being developed, see Section 4.B for a summary.

The ultrashort pulses from a mode-locked laser result in high peak power, which enables efficient nonlinear effects for spectral broadening or shifting to the UV or the mid-IR using an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) [141–144] or difference-frequency generation [145, 146]. (See [147] for an overview of comb sources for spectroscopy.) The mode-locking process reduces pulse-to-pulse amplitude fluctuations, which typically results in lower RIN even after spectral broadening than a supercontinuum source. However, the spectrum is often significantly more structured with 10 dB or more variation common. Even after spectral broadening, frequency comb sources are also still typically less broad than supercontinuum sources. The advantage of frequency combs though is the lower noise and the increased spectral resolution and accuracy from the comb structure. In addition, the comb structure enables efficient cavity coupling for increased path length (Section 3.E).

2.B. Absorption cells

There are four different types of gas cells shown in the center of Figure 1: a single-pass cell, multipass cell, a resonant cavity, and an open-path system. A single-pass cell is clearly the simplest, might have an effective length of 10 cm to 1 meter and has a spectral bandwidth limited only by the cell windows. A multipass cell uses aligned concave mirrors with an effective path length of 1 m to 400 m [155–157]. The spectral bandwidth and transmission is limited by the multiple mirror bounces. It is relatively easy to couple in to and out of these cells. In addition, they are relatively insensitive to mechanical vibrations, which makes them attractive for field systems.

A resonant cavity can provide 10 km or more of effective path length but requires well-aligned, high-reflectivity mirrors. The effective path length L(λ) is set by the optical losses within the cavity (mirror transmission, scattering, absorption) and is parameterized by the finesse, ℱ(λ) = π/(losses(λ)): L(λ) varies between ℱ(λ)/π to 2ℱ(λ)/π depending on the configuration [158, 159]. Spectroscopy systems use either the fundamental spatial mode, particularly if used with a spatially coherent source, or multiple spatial modes of the cavity, particularly if used with a spatially incoherent source. The challenge for broadband spectroscopy lies in the tradeoff between spectral bandwidth and mirror reflectivity (or path length); typically high finesse can only be maintained for ~10% of the center wavelength. This tradeoff becomes more challenging as one moves from the visible/near infrared into the mid infrared and UV, where the quality of mirrors degrades, which also results in lower throughput for a given mirror reflectivity.

Open-path systems replace the cell with a long open-air sample, often with a reflector so that the light returns to the source where the spectrometer is also located. These systems typically have absorption paths ranging from several hundred meters to 10+ kilometers. The introduction of a long open path is complicated by the presences of atmospheric turbulence, which will both reduce the return power through beam pointing effects and add noise through scintillation. This scintillation is a concern for any scanning system, unless the scan speed is significantly faster than the time scale of scintillation (typically on the order of 10–100 ms, see e.g. [160]), and can result in RIN in the spectrum.

2.C. Detection approaches

In general, the detection systems for broadband spectroscopy can be divided into two broad categories: time-domain acquisition as in Fourier transform spectroscopy, dual-comb spectroscopy, or THz-time domain spectroscopy, and frequency-domain systems as in grating spectrometers or more complicated spectrographs. Each of these systems provide different combinations of wavelength coverage, spectral resolution, number of resolved spectral elements, and time resolution.

The technique of Fourier transform spectroscopy is extremely well developed and discussed in detail in several textbooks [161, 162]. Essentially, one measures the time-domain response of the gas; a Fourier transform then provides the spectrum. Such systems can operate with a single photodetector, which makes them very versatile in terms of spectral coverage. The resolution for a scanning system is typically 0.01–1 cm−1(0.3–30 GHz), with the highest resolution laboratory systems around 0.0003 cm−1(10 MHz). The number of spectral elements is flexible and can be up to 100,000 or more.

The spectrograph category ranges from a low-resolution grating spectrometer to a high-resolution two-dimensional spectrometer that combines a high-dispersion element such as a virtually-imaged phase array (VIPA) etalon [163] (or an Echelle grating [164]) to achieve superior resolution as illustrated in Figure 1. A low resolution spectrometer might have a resolution of ~1 – 10 cm−1(or 0.025 – 2.5 nm at 500 nm) in the visible and near infrared, while a high-resolution spectrometer can reach 0.03 cm−1 resolution. In either case, the dispersed output of the spectrometer is directed to a focal plane array for simultaneous detection of multiple spectral channels (typically 1000–3000, limited by the size of the array). In the visible and near infrared, relatively inexpensive, robust, and high sensitivity Si or InGaAs focal plane arrays are available. Further into the infrared, focal plane arrays are significantly more expensive and have reduced performance.

Regardless of the spectrometer type, if used with a frequency comb source then there is a qualitative difference between situations where multiple comb teeth fall within a single resolution element versus situations where at most one comb tooth falls within a resolution element. In the former, the frequency resolution is set by the spectrometer ILS (instrument line shape) and any frequency accuracy is derived from calibration against known spectra. In the latter, the resolution is set by the narrow comb tooth width (at least for the full width half maximum) and the accuracy is derived directly from the frequency comb. This comb tooth resolution has been achieved for highly coherent dual-comb systems (e.g., [165]), in VIPA-based spectrographs (e.g. [163]), and in Fourier transform spectrometers, particularly if the sampling is synchronous with the comb repetition rate ([166]).

2.D. Sensitivity limits

There are many ways to define the sensitivity of a broadband spectrometer. Research geared towards specific applications will often quote the minimum detectable concentration of the target species which is useful when comparing optical instruments to mass spectrometers. However, this depends on the cross section for that molecule (see Equation 1), which makes comparison between optical systems that measure different species difficult. Instead, in Table 5, we quote the minimum detectable absorbance signal – the quantity (Nσ(ν)L)min – which is the inverse of the mean signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) over a normalized acquisition time (e.g. 1 second).The sensitivity will be wavelength dependent and is often quoted at its peak or averaged over some central portion of the spectrum. It is possible to further normalize by the effective path length to yield an absorbance sensitivity in units of cm−1, which is often done for systems with long interaction lengths through the use of resonant cavity. Finally, in order to compare with swept laser systems, researchers sometimes further normalize by the square root of the number of spectral elements. However, because broadband systems typically cover a much larger spectral range than a swept cw laser, such a comparison is not particularly useful. Indeed, it is important to accept that the spectral SNR of a broadband system will never rival that of a single-frequency system because of spectral brightness limitations. (This reduction is ameliorated to some extent by the fact it is the integrated area of a gas spectrum rather than a peak absorbance that sets its minimum detectable concentration.) Finally, we note that sensitivity is just one feature of any broadband spectrometer and there are always tradeoffs in path length, central wavelength, overall bandwidth, resolution, sensing geometry etc. A system optimized for sensitivity is not as useful, for example, as compared to a fieldable system optimized for the detection of a particularly important trace gas against a cluttered background.

Table 5.

Comparison of system sensitivity (both incoherent and laser-based using a variety of detection methods). They are given in approximately chronological order. SC: Supercontinuum light source. FC: Frequency Comb. We have selected a high sensitivity example from each type of system (e.g. CE-DFCS + VIPA detection) to give a general idea for the sensitivity but these numbers will vary some for each system depending on the exact configuration.

| Ref | System | Light Source | Absorption Cell | Detection system |

|

Eff. Path (km) | Resolution (GHz) | Bandwidth/Center λ (nm)/(nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [167] | OP-FTIR | Thermal | Open Path | FTS | 1.7×10−2 | ~ 0.4 | 30 | 22000/13600 | |

| [168] | BB-CRDS | Dye Laser | High-finesse cavity | Grating + CCD | 4.1×10−2 | 30 | 140 | 20/660 | |

| [169] | LP-DOAS | Xe-arc | Open path | Grating + PDA | 1.6×10−2 | 4.4 | 620 | 45/440 | |

| [130] | IBB-CES | SC | High-finesse cavity | Grating + CCD | 4.3×10−3 | 19 | 70 | 30/670 | |

| [170] | CE-DFCS | FC | High-finesse cavity | VIPA | 6.0×10−3 | 14 | 0.8 | 25/1600 | |

| [171] | CE-DOAS | LED | High-finesse cavity | Grating + PDA | 1.6×10−3 | 13 | 810 | 50/460 | |

| [172] | CE-DFCS | FC | High-finesse cavity | FTS | 7.2×10−4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 200/3760 | |

| [173] | CE-DFCS | FC | High-finesse cavity | Grating + CCD | 8.6×10−5 | 9.2 | 13.5 | 4/430 | |

| [174] | DCS | FC | Single-pass cell | Dual Comb | 9.3×10−4 | 7.5×10−4 | 0.1 | 100/1562 | |

| [175] | NICE-OFCS | FC | High-finesse cavity | FTS | 2.0×10−3 | 0.66 | 2 | 30/1575 | |

| [176] | DCS | FC | Open Path | Dual Comb | 3.4×10−2 | 2 | 0.1 | 70/1635 |

With these caveats, we note there are two types of noise that limit the spectral SNR: (i) white noise that varies randomly across spectral bins as might result from detector noise, shot noise, broadband laser relative intensity noise (RIN), or digitization noise and (ii) structured or baseline noise that might result from etalon effects, slow variations in the broadband spectrum between normalizations, or other optical and electrical 1/f noise. The former will dominate for short averaging times and the latter for long averaging times. Practically, the baseline noise sets the final sensitivity limit. It depends strongly on system design and thus it is difficult to make any general statements.

On the other hand, the random white noise contribution can be analyzed. Discussions of sensitivities for different broadband systems have been presented elsewhere (e.g., Chapter 6 of [161] and [177–179]), so we highlight only a few points here. First, while broadband spectrometers have historically been light limited, as in FTIR or DOAS, that same limit is generally not true with the advent of laser-based broadband sources. In these systems, the maximum signal-to-noise is obtained by increasing the power until detector saturation occurs or relative intensity noise (RIN) becomes the dominant noise source. Both of these cases effectively reflect a “dynamic range” limit. Because of this limit, in non-light-limited situations broadband spectrometers often do not realize the full sensitivity advantage that should be possible due to the higher spectral brightness of laser-based sources (see Figure 2). Instead, researchers can exploit the high spectral brightness by incorporating a much longer effective path length or open path, which is “penalty-free” since the additional insertion loss simply reduces the total power but does not degrade the dynamic-range limited SNR. Second, there is a fundamental difference in the sensitivity between dispersive spectrometers and Fourier transform spectrometers, which arises from the fact that noise is re-distributed across spectral elements after the Fourier transform [161]. Depending on the noise limit, a Fourier spectrometer can result in an improved spectral SNR (if detector-noise limited) or lower SNR (if dynamic-range limited) compared to dispersive detection [161, 180]. However, the gain in wavelength coverage and number of spectral elements from an FTS often outweighs this potential loss.

3. SPECIFIC IMPLEMENTATIONS

3.A. Fourier transform spectroscopy (FTS)

Fourier transform spectroscopy (FTS) using incoherent light sources (including sunlight) was developed in the 1950s [181, 182], see Refs [183, 184] for an interesting history, and soon became the standard infrared spectrometer. In fact, the interest in broadband spectroscopy stems in large part from the remarkable success of FTIR spectrometers, and FTIR data forms the basis for many molecular databases. In addition, FTIRs with incoherent sources have been used to support many of the applications discussed earlier. Commercially available spectrometers can cover up to 5–50,000 cm−1by interchanging detectors and light sources (typically incoherent, thermal sources). The resolution varies between 1 cm−1 for small, portable systems to ~0.001 cm−1 for the highest resolution instruments with 10-m optical delay paths. However, because of the incoherent source, there is a tradeoff between sensitivity, path length, and spectral resolution. In particular, path length enhancement with optical cavities typically results in low sensitivity. Additionally accurate measurements require periodic recalibration [185, 186].

In breath analysis, FTIR was able to detect several VOCs (including hexane, methyl ethyl ketone, toluene, ethanol) in breath [187] at a detection limit of ~1 ppmv using a 4.8-m absorption path. This sensitivity level is suitable for assessing environmental exposure but below the VOCs concentration in normal breath. FTIR was also used to measure δ13CO2 (using the strong CO2 band at 4.3 μm) with a precision of ~0.1 ‰(after a correction for temperature drifts) in both atmospheric and breath samples [186] in measurement times of ~2–6 min, although the accuracy (with frequent re-calibration) was not given. In addition, the resolution is not sufficient for many isotopes.

Open path FTIR (see [188, 189] for brief introductions) has been used for several decades in a variety of different applications such as quantification of VOC pollution from manufacturing facilities (e.g., [167, 190, 191]), mapping of NH3 emissions from agricultural facilities (e.g., [192, 193], measurement of greenhouse gases (e.g., [194, 195]), and quantifying biogenic VOC emissions [196]. These systems typically have 100–1000 m path lengths and achieve an integrated absorption sensitivity of 1–10 × 10−3 at a resolution of 0.5–1 cm−1 with measurement times on the order of several minutes (limited by the incoherent light sources), longer paths or higher resolution result in reduced sensitivities. This gives detection limits typically in the range of 10s of ppbv for a range of VOCs; however, even with calibration, absolute quantification and agreement between instruments is limited to 10–30% due to uncertainties in the baseline level and the instrument line shape [197, 198].

The time resolution of a continuously-scanning FTS is limited by the time required to scan the optical delay, which is too slow to support chemical kinetic studies. However, higher time resolution can be obtained by using a time-resolved step-scan FTS [199, 200] for repetitive events that can be triggered at a precise time (for example, chemical reactions initiated with laser photolysis). Time-resolved FTS has been used to measure the kinetics of Criegee intermediates, which are formed during the reaction between ozone and alkenes and are thought to be important oxidizers of SO2 and NO2 [201–203]. The small Criegee intermediates (CH2OO and CH3CH2OO) formed from the photo-initiated reaction of iodine-substituted hydrocarbons with O2 were found to have an unexpectedly fast self-reaction rate [204] and conformer-dependent reaction rates in a mixture NO/NO2 [205]. In addition, the first direct observation of the stabilized Criegee intermediate formed during the ozonolysis of any alkene (in this case β-pinene) was recently accomplished using time-resolved FTS [40].

FTIR systems are commonly used because of the wide wavelength coverage and relative simplicity; however, the sensitivity is not as high as possible due to the the spatially incoherent light source, which limits the path length, and the temporally-multiplexed detection. Given the ubiquity of FTIRs, it is natural to consider replacing the conventional source with either a super-continuum source or frequency comb for increased path length, added sensitivity, or added speed. There have indeed been a number of systems that have done this, e.g., [137, 206–209]; however, some disadvantages of coupling a coherent source with FTIR are that coherent sources are not truly as broad-band as, e.g., a globar and that detection electronics need to be modified to use the additional light available from these sources. In addition, the high RIN of supercontinuum sources can result in lower sensitivity [137]. The sensitivity limitations of FTIR systems have led to the continued development of other techniques as discussed below.

3.B. Incoherent Broad-Band Cavity-Enhanced Spectroscopy (IBB-CES) and Cavity-Enhanced Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (CE-DOAS)

Incoherent Broad-Band Cavity-Enhanced Spectroscopy (IBB-CES) and Cavity-Enhanced Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (CE-DOAS) are two physically identical measurement techniques based on coupling incoherent broad-band light sources to high finesse cavities. IBB-CES is also called Incoherent Broad-Band Cavity-Enhanced Absorption Spectroscopy (IBB-CEAS) or Broad-Band Cavity-Enhanced Absorption Spectroscopy (BB-CEAS). However, these measurements are actually extinction measurements rather than absorption, i.e. include Rayleigh scattering so we favor IBB-CES. In addition, we prefer to leave “incoherent” in the name to differentiate these LED-based instruments from the cavity-enhanced laser-based instruments discussed later.

These techniques are most often used in the visible and the near-UV, where there exist good detectors and mirrors and strong molecular cross sections, though some systems have recently been built in the near-IR. Initially an Xe-arc lamp was used for the light source [210]. Supercontinuum light sources have also been used more recently e.g. [130, 138]. However, LEDs are most often used since their power requirements are quite low. LED-based instruments tend to be small –with cavities of < 1 meter in physical length – simple, and portable. Typically spectra are recorded on temperature-controlled grating spectrometers. Wavelength calibration is provided by measuring a solar spectrum and instrument line shapes are often determined by measuring lines from e.g. a Hg-line lamp. The instruments do generally require gas cylinders for measuring the mirror reflectivity, calculating the path length, and recording the reference spectrum. They have successfully been deployed on ships and aircraft [21, 211].

These systems, particularly those using LEDs as light sources, are light-limited and photon shot noise or detector noise set the noise limits. This typically limits them to at best minute time resolution. Despite the low photon level, the sensitivity can be excellent because the high finesse of these cavities translates to very long path lengths, often in the range of several to tens of kilometers. For example, the system by Thalman et al. [171] has a path length of up to 18 kilometers. These long path lengths translate to very sensitive detection limits, down to single-digit parts per trillion by volume (depending on molecular cross section strength). Accurate concentration retrievals require careful calibration of the wavelength-dependent path length [171, 212]. Finally, while these systems have several orders of magnitude of linearity, the signal can saturate at concentrations of tens of parts per billion by volume (depending on cross section strength and path length) so they are most commonly used for measuring trace gases with very low mixing ratios.

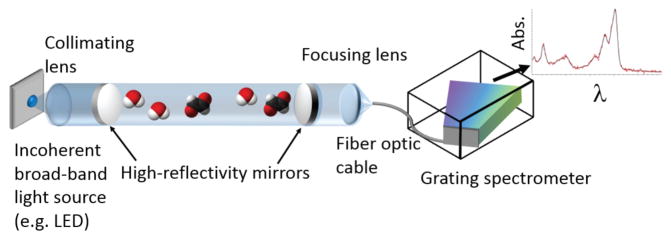

Figure 3 shows a typical instrument that was designed to measure glyoxal (CHOCHO), methylglyoxal (CH3COCHO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and the collision-induced oxygen dimer (O4) in the blue spectral region [171]. The broad-band light source was a blue LED centered at 465 nm that is collimated with a 2” f/1 lens, and filtered with a 420-nm long-pass filter (to prevent UV light from entering the cavity and photolyzing trace gases or initiating reactions). A portion of the light is coupled into a 100-cm resonant cavity. The light exiting is the cavity is filtered with a band pass filter to remove the green light in the tails of the LED spectrum and focused into a f/4 single-core glass optical fiber and analyzed with a Czerny-Turner grating spectrometer.

Fig. 3.

Example simplified schematic of IBB-CES and CE-DOAS setups. These consist of an incoherent light source, a collimating lens, a cavity made of a pair of highly reflective mirrors, a focusing lens after the cavity, and a fiber optic cable to transfer the light to the grating spectrometer. Data: example CE-DOAS glyoxal measurement (red: measured spectrum, black: fitted cross section).

The distinction between IBB-CES and CE-DOAS lies in the data analysis. They are both based on Beer-Lambert’s law (Eq. (1)). In IBB-CES, the entire broadband spectrum is analyzed after correcting for the mirror reflectivity and Rayleigh scattering [212] and measuring I0 using purified atmospheric air. In contrast, DOAS retrievals remove the broad-band part of the spectrum through a polynomial baseline fit and fit only the narrow band absorbers, thereby relaxing the need for a reference spectrum but limiting detection to molecules that have absorption cross sections that vary rapidly with wavelength. These different processing methods highlight an important issue in any broadband spectrometer, namely the flatness of the spectral response over broad frequency bands and the stability of the light source. This also results in slightly different data acquisition methods: reference spectra are taken significantly more frequently for data that will be analyzed via IBB-CES and significantly less frequently for data that will be analyzed via DOAS.

These systems have found many applications in atmospheric monitoring, both in the lab and in the field. LED-based systems have been used in the UV to measure aerosol extinction [22] and O3 [213]. They have been used in the blue to measure O4, NO2, IO, glyoxal, methylglyoxal, H2O [171, 214–217] and in the green spectral region to measure NO3, NO2, and I2 [218]. Xe-arc lamps have also be used in the green to measure I2, IO, and OIO [219]. LEDs have been used in the red spectral region to measure O2, H2O, NO2, NO3, NO3 + N2O5 [215, 218, 220, 221]. Supercontinuum light sources have also been used in the red [130] and near-IR to to measure CO2, H2O, and C2H2 [138, 139]. Very recently, a diode laser-pumped Xe plasma was used for measurements from 315–350 nm, below the range of LEDs [222].

3.C. Long-path Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (LP-DOAS)

In LP-DOAS, the cell is replaced by a 100-m to 5-km open air path terminated by a retroreflector array [24, 223]. Xe-arc lamps are needed to supply sufficient spectral brightness, but then limit measurements to fixed locations with sufficient electrical power. The DOAS processing reduces sensitivity to the exact I0 spectrum, which is measured directly at the light source. This DOAS technique measures species with strong differential cross sections, essentially small molecules in the UV and visible, including HONO, NO2, HCHO, O3, and NO3. Unlike the cavity-based system, LP-DOAS is also free of wall losses and sampling line losses, providing a true path-averaged in situ measurement. These instruments also tend to be light-limited so photon statistics determine the detection limit although other systematics (such as residual structure) also play a role. Typical systems can achieve a minimum detectable optical density of 5×10−4 in ~5 min [24], which gives detection limits in the few to hundreds of parts per trillion by volume for trace gases, including 160 pptv for NO2, 830 pptv for formaldehyde, and 78 pptv for HONO.

LP-DOAS has been used for atmospheric measurements for decades (e.g. [224–226]). It was used to measure O3, NO2, SO2, HCHO, HONO, BrO, ClO, and IO in the marine boundary layer in Mace Head, Ireland [227]. During a large campaign in Mexico City in the spring of 2003 LP-DOAS measured glyoxal, HCHO, NO2, and O3 across a 4.42 km path in the blue and UV spectral regions [169]. Another LP-DOAS instrument measured formaldehyde and a number of aromatics during the same campaign [228]. This technique was also used to measure vertical profiles of NO2, NO3, O3, HONO, and HCHO in Phoenix, Arizona [229] and to obtain vertical profiles of O3, SO2, NO2, HCHO, and HONO over Pasadena, California during CalNex 2010 [230]. Detection limits for this technique range from 3.2 pptv for NO3 to 2.3 ppbv for O3 (measurement time not specified) [230].

3.D. Broad-Band Cavity Ringdown Spectroscopy (BB-CRDS)

Cavity ringdown spectroscopy (CRDS) uses a laser source coupled into a high finesse cavity. The laser is turned on for a period of time to let light build up in the cavity, and then turned off at which point an exponential decay of the light is detected. The decay rate is compared in the presence and absence of an absorber, which allows the concentration of the absorber to be calculated [231, 232]. The advantage of this ring-down approach is that is insensitive to amplitude noise of the source. However because traditional CRDS is done at a single wavelength, it is subject to interferences by other species that absorb at the same wavelength and cannot be used to retrieve multiple species simultaneously.

Broad-band CRDS can circumvent this limitation. BB-CRDS has been achieved in a number of ways by coupling lasers to high-finesse cavities, see the comprehensive review of early techniques in [168]. The first demonstration measured the O2 A band. They used a pumped dye laser with a 400 cm−1 spectral bandwidth, coupled to a cavity with an effective path length of 560 meters. Light exiting the cavity was coupled to a FTS followed by a photomultiplier tube, which allowed the users to collect ring-down spectra for individual wavelengths by setting the mirror position on the FTS [233]. A second demonstration presented a technique called ringdown spectral photography (RSP) to measure propane. This also used a Nd:YAG-pumped dye laser that was then directed onto a mirror that rotates, scanning the light across a diffraction grating which then directs the diffracted light onto a 2-D CCD camera using streak detection [234]. This was the first implementation to achieve simultaneous time and wavelength resolution, as the work in [233] measured single wavelengths at a time from a broad-band source. Another demonstration used a Nd:YAG-pumped dye laser coupled to an imaging spectrometer plus a clocked 2-D CCD camera to measure NO3 and H2O [168, 235]. Yet another demonstration coupled a frequency comb to a cavity and aligned the comb pulses with the cavity modes. This used a detection system very similar to the RSP system [236].

3.E. Cavity-Enhanced Direct Frequency Comb Spectroscopy (CE-DFCS)

In cavity-enhanced direct frequency comb spectroscopy (CE-DFCS) or mode-locked cavity enhanced absorption spectroscopy (ML-CEAS), a frequency comb is coupled into a high-finesse cavity, as discussed in several recent reviews [147, 158, 209]. The advantage of using frequency combs is that the cavity mode spacing and comb mode spacing can be matched, so a significant fraction of the comb light is coupled into and out of the cavity. However, due to dispersion in the enhancement cavity, this matching is only possible over some limited bandwidth. Moreover, it is technically challenging. There are two primary ways of ensuring this matching of comb and cavity modes: the first is a swept lock where the comb teeth and cavity modes are periodically swept into resonance with each other [158, 237], while the second is to maintain a tight lock between the comb teeth and the cavity modes, typically using a Pound-Drever-Hall locking scheme [172]. In the latter, frequency noise can be mapped to amplitude noise, thus reducing the sensitivity unless this noise is suppressed, e.g. [175, 179]. The swept approach removes this problem by rapidly integrating over the cavity transmission peak, avoids the cavity-dispersion limitation to the spectral bandwidth, and avoids the problem of lineshape distortion [172]. However, the swept approach reduces the transmitted light and adds a temporal variation to the transmitted intensity, which can be problematic for some detection methods.

The cavity-transmitted light must then be spectrally detected. Several different detection systems have been used for CE-DFCS: dispersive spectrographs using a grating spectrometer (e.g., [173, 237]) or a VIPA spectrometer (e.g., [41, 92, 170]), scanning Fourier-transform spectrometer (e.g., [172, 179, 238]), and dual comb spectroscopy ([239, 240]). Each measurement system has its own set of compromises for spectral coverage, resolution, measurement speed, and noise performance (i.e., suppression of amplitude noise from the cavity-comb coupling). A summary of some demonstrated CE-DFCS systems illustrating these tradeoffs is given in Table 5.

In support of breath analysis, Thorpe et al. performed an initial demonstration of the measurement of NH3, CO, and CO2, as well as isotope ratio measurements for CO2 in breath using near-IR CE-DFCS [170]. They obtained an absorbance sensitivity of 2 × 10−3 in a 30 s measurement time using a 1.5-m-long cavity with an effective path length of 27 km. This provides a detection limit of 900 ppbv for CO and a projected sensitivity for NH3 (determined by measuring NH3 in N2 and comparing with the breath spectrum) of 18 ppbv. Because of the low linestrengths in the near-IR, these detection limits could be improved by moving to other wavelength regions.

CE-DFCS has been applied to atmospheric measurements in the field. In Ref. [241, 242] IO, BrO, and NO2 were measured for several months at a coastal East Antarctic site. In this system, the frequency comb source was coupled into two ~90-cm long cavities with a finesse of 6,000 at 338 nm or 32,000 at 436 nm using the swept lock and detected with a 0.45 cm−1(5 pm) resolution spectrometer. The system achieved a minimum detectable absorbance of ~9 × 10−5 in 1 min, which is an order of magnitude lower than the comparable LED-CE-DOAS system [217] and two orders of magnitude lower than comparable IBB-CES systems [212, 214]. The tradeoff here is increased weight, power consumption, and complexity. The measured 1σ detection limits were 1 pptv for BrO, 100 pptv for H2CO, 40 ppqv for IO, and 10 pptv for NO2 with 1 min acquisition time.

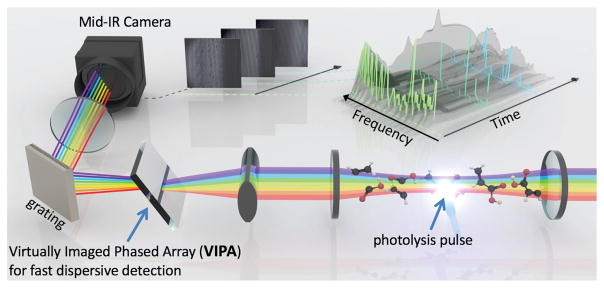

CE-DFCS has also recently be adapted to measure rapid chemical kinetics in a technique called time-resolved frequency comb spectroscopy (TRFCS), as shown in Figure 4. In the first demonstration of this technique [41], the production of the trans-DOCO radical from the photodissociation of deuterated acrylic acid was measured with a time resolution of 25 μs. This system is based on a mid-IR frequency comb source plus a VIPA spectrometer for frequency resolution and obtains high time resolution by gating the integration time of the camera. The simultaneous bandwidth is limited by the spectrometer to 65 cm−1 and is tunable over a wide range. The broad spectral bandwidth enabled the measurement of the precursor (i.e., deuterated acrylic acid) depletion, reactive radical (trans-DOCO), and final products (HDO and D2O). In addition, a completely unexpected species, deuterated acetylene, was observed as a prompt photodissociation product. This suggests that even this fairly simple photodissocation process is not well understood and illustrates the advantage of broad bandwidth for kinetics measurements. Subsequent measurements applied this system to studies of the OD+CO reaction, which is important in both atmospheric chemistry and combustion dynamics, and provided the first direct measurement of the trans-DOCO radical formed during this reaction [42].

Fig. 4.

TRFCS. Laser light enters the cavity where a pulse starts the reaction through photolysis. Here, a VIPA spectrometer is used for detection. By measuring spectra at varying delays after the pulse, a complete kinetic picture can be determined (inset). Figure credit: The Ye Lab and Brad Baxley/JILA

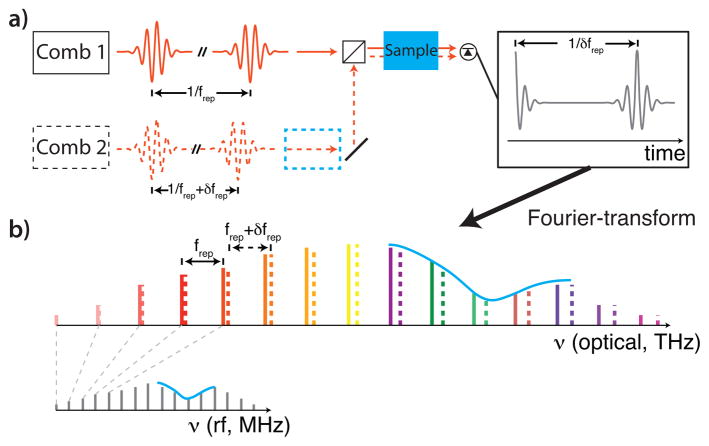

3.F. Dual comb spectroscopy (DCS)

The basic concept of a coherent dual comb spectrometer is illustrated in Figure 5 and is reviewed in [178]. This technique relies on the interference between two combs with slightly different repetition rates. In the frequency-domain picture, the two combs have slightly different tooth spacings so that their heterodyne beat signal leads to a comb in the rf domain, thus mapping the optical information to easy-to-measure rf signals. In the time-domain picture, the two comb sources produce pulse trains with different periods. As the pulses from one comb “walk through” the pulses of the second comb, the pulse-by-pulse overlap is digitized. This results in a scanning much like the interferometer used in FTS, but with the scanning done optically. The resulting interferogram is a down-sampled measurement of the source pulse after transmission through the gas; any gas absorption signature appears as a trailing free-induction decay. For high SNR, the dual comb spectrometer requires high coherence between the combs [177, 243], which can be accomplished with optical locking or signal processing. Most DCS systems are currently limited to the near-IR, where robust comb sources exist, but there is ongoing work to develop systems in the mid-IR to access the larger molecular cross sections [178].

Fig. 5.

Dual comb spectroscopy, see text for details: (a) time-domain picture, (b) frequency-domain picture. The sample can be placed either before the combiner (dashed blue box) to measure both phase and absorbance or after the combiner (solid box) to measure only absorbance.

The time required to acquire a single interferogram is given by the difference in the comb repetition rates, 1/δfrep, and can be on the order of milliseconds. However the Nyquist sampling criterion limits this interferogram acquisition rate to , where frep is the comb repetition rate and δν is the spectral bandwidth. Only then is there the desired one-to-one correspondence between the rf comb teeth and pairs of optical comb teeth. In other words, the broader the spectrum or lower the comb repetition rate difference, the longer the interferogram takes. Higher time resolution can be obtained with apodization, but this results in lower spectral resolution and prevents mode-resolved measurements.

DCS is potentially well-suited to atmospheric measurements since the high frequency resolution makes it possible to measure multiple species simultaneously in a complex background. Additionally, the coherent and collimated laser light allows significantly lower optical powers of light to be used in comparison to long-path DOAS (see Section 3.C). The rapid acquisition rate also eliminates potential spectral distortions due to atmospheric turbulence. However, the added complexity of the system has resulted in a limited number of demonstrations of open-path DCS. The first demonstration was used to temporally resolve NH3 plumes from an open gas cylinder outside of a lab [244] across a 44-m-long path. This experiment used two mid-IR combs created from difference-frequency generation of 125-MHZ Ti:sapphire lasers focused in to Ga:Se crystals. This produced 10 μW of mid-IR light covering 840–1120 cm−1(8.9 to 11.9 μm). Spectra were measured at 2 cm−1 resolution with a 70 μs update rate; however, the sensitivity and accuracy were limited due to the unstabilized combs.

The first quantitative demonstration of open-path DCS was used to measure the greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, H2O, and HDO over a 2-km round-trip path [176] using laboratory-based combs. This work was done in the near-IR (6000 to 6250 cm−1or 1.60 to 1.67 μm) using overtone bands of the gases. Two erbium fiber-frequency combs with 100 MHz repetition rates were used as the light source. They were combined and launched off a telescope to a 50-cm diameter plane mirror located 1 km away from the light source. The light was reflected back to the source, collected in a fiber, and sent to a detector. This system was also used to measure spectral phase by launching only a single comb (see Figure 5 and [245]). An open-path measurement over ~26 meters round-trip was also done with a single comb (rather than a dual comb setup) in the mid-IR to measure CH4 and H2O [246]. They used a pumped OPO to created the comb spectrum, sent the light over 13 meters to a retroreflector, and collected the light with a telescope before sending it to a VIPA and camera for detection.

Dual frequency comb spectroscopy with coherent, stabilized combs is also a new tool for generating precise spectra in support of improved molecular databases because of the negligible instrument line shape. Zolot et al. [104] demonstrated broadband, high accuracy measurements of C2H2 and CH4 using dual frequency comb spectroscopy cover 5800–6700 cm−1(1.5–1.7 μm). They determined a systematic uncertainty on the line centers of 0.2 MHz (7 × 10−6 cm−1) and an SNR-limited precision of ~ 10−4 of the line width on the strongest lines. DCS has also be used to simultaneously cover 5260–10000 cm−1(1.9–1.0 μm) [105] while still maintaining high precision and accuracy, allowing retrieval of line centers of C2H2, CH4, and H2O. Baumann et al. [103] have demonstrated a line center accuracy of 0.3 MHz for CH4 using DCS in the mid-infrared, which is an order of magnitude below the accuracy of FTIR measurements. DCS can also provide new information about line broadening parameters; for example, Iwakuni et al. [247] recently measured nuclear-spin-dependent pressure broadening in acetylene in the near-IR.

3.G. THz Time-Domain Spectroscopy (THz TDS)

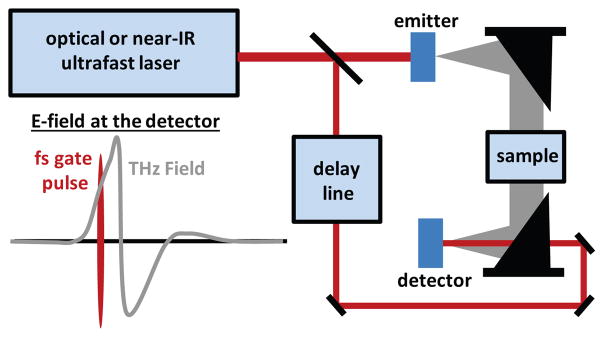

The most widely used broadband THz spectroscopy is likely THz time domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS). In THz-TDS, one measures the electric field of a THz pulse in the time domain after transmisison through a sample. This enables the direct determination of the broadband optical constants of a material [248]. Additionally, THz-TDS can be used in studies of ultrafast dynamics, as the THz pulses are single-cycle and near transform limited in the time domain [249]. The spectral coverage, given by the Fourier transform of the THz pulses, can be very broad, often covering 10 THz or more for a particular source/detector combination, with a high peak dynamic range (>60 dB) [248]. Another common feature of THz-TDS pulses is their fixed carrier envelope phase (CEP) offset, which is a requirement for repetitive time domain electric field sampling. The resolution of THz-TDS instruments is typically ~1 GHz (limited by the length of mechanical delay lines), but the fixed CEP of oscillator-based systems can be exploited for resolutions of <10 kHz, particularly in asynchronous optical sampling (ASOPS) designs [154, 250, 251].

A typical THz-TDS setup is shown in Figure 6, and consists of an ultrafast laser (often Ti:Sapphire or fiber based), THz emitter, optical delay line, and THz detector. Here, we discuss several emitter/detector methods that have been used for THz-TDS, and emphasize the inherent trade-offs of each. Most emitter techniques can also be used for detection, but the emitter and detector need not be based on the same proceess. For example, a plasma emitter can be used with a nonlinear crystal detector, or vice versa.

Fig. 6.

A generalized THz-TDS setup. The ultrafast pulses from an optical or near-IR laser are used to generate and detect THz transients. Detection is performed in the time domain with an optical delay line, and is sensitive to the THz electric field. This allows the measurement of the real and imaginary optical constants of a sample.

The earliest THz-TDS designs used a photoconductive antenna (PCA) switch as both emitter and detector [252]. This method is still used in oscillator-based systems for moderate bandwidths of several THz [251], and can be extended to 20 THz of generation bandwidth with sufficiently short optical pulses [253]. The active area is often improved with an interdigitating arrangement [254].

Nonlinear crystals comprise the second major class of THz-TDS emitters and detectors. Inorganic crystals with a large second-order (nonlinear) susceptibility, such as ZnTe, GaP, LiNbO3, GaAs and GaSe, are most commonly used for THz generation via optical rectification and difference frequency generation [255–260]. Organic crystals, such as DSTMS, DAST, and OH1, have also been used due to their exceptionally large nonlinear coefficients [261]. Phase-matching between the optical or near-infrared pump light and THz light as well as crystal phonon absorptions can limit the bandwidth and conversion efficiency attainable with a particular nonlinear crystal. This leads to an inherent tradeoff between bandwidth and conversion efficiency for different nonlinear crystals in various sections of the THz. Nevertheless, THz generation from nonlinear crystals pumped by amplified ultrafast laser systems have yielded some of the largest THz pulse energies (~270 μJ ) [261] and focused field strengths (50 MV/cm) [262] of any THz technique, enabling the first demonstrations of broadband multidimensional THz spectroscopies of gases [263], liquids [264, 265]. and solids [266].

The third, and most broadband, class of THz-TDS techniques is two-color plasma filamentation [267, 268] and the related air-based coherent detection [269, 270]. The main difficulty of these techniques is their reliance on ultrafast amplified laser systems with mJ level pulse energies. For generation, a focused, high intensity pulse with frequency ω ionizes the molecules or atoms in a gas, creating a plasma. By spatially and temporally overlapping a second ultrafast pulse of frequency 2ω on the plasma, broadband THz radiation is generated that can span >100 THz of bandwidth [271]. For plasma detection, an intense gating pulse of frequency ω is focused to generate a second gas plasma and overlapped with the THz radiation between a pair of biased electrodes [269]. The mechanisms of THz generation are still under active investigation, but involve a combination of four-wave mixing, asymmetric photo-induced currents, and current oscillations [272]. The broadband pulses from two-color plasma filamentation are attractive for linear spectroscopic applications, as they provide continuous coverage from the microwave to the mid-infrared regions of the spectrum. Their subcycle temporal profile and relatively intense pulse energy are also ideal for studies of the coherent control of materials.

As in other spectral regions, broadband THz sources can also form frequency combs, either by downconversion of a modelocked near-infrared oscillator (often in a THz-TDS setup) [154, 250, 251, 273], directly from a THz quantum cascade laser [274–276] or from coherent synchrotron radiation [277]. Downconversion to a THz comb is typically accomplished with a photoconductive antenna (PCA) or a nonlinear crystal. A PCA emitter driven by an 800 nm 80 MHz oscillator can generate a THz comb spanning 2.5 THz with ~10 μW total power spread over ~30,000 comb teeth (~300 pW/tooth). Broadband detection of a THz comb has been demonstrated with ASOPS THz-TDS [154, 250, 251, 273], and is directly analogous to dual comb techniques used at higher frequency (see Section 3.F).

THz combs can also be generated from coherent synchrotron radiation (CSR), which can provide total powers of 60 μW over bandwidths of ~1 THz. In an initial demonstration, a comb tooth spacing of only 846 kHz was reported (20 pW/tooth), due to the long revolution period of the electron bunches in the synchrotron storage ring [277]. This spacing is well-suited for molecular spectroscopy, as it is near the Doppler linewidth of small molecules in the THz range. However, unlike other approaches, a CSR source requires a dedicated user facility.

Finally, new laser sources have recently been developed in the THz region. In particular, quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) can directly emit in the THz region with milliwatt output powers and octave spanning bandwidths [278]. QCLs can also be quite compact, which could lead to monolithic THz comb sources. Modelocked THz QCLs should form a comb, have so far been limited to narrow bandwidths (0.1 THz) [279]. QCL combs generated from four-wave mixing can generate larger bandwidths (0.6 THz), with integrated dispersion compensation [274, 276]. In these designs, 70–80 teeth can be produced with milliwatt power levels, or individual tooth powers of ~50 μW. They are only suitable for frequency domain applications, however, as they do not form time-domain pulses [274].

The absorbance sensitivity at 1 s of averaging of THz TDS instruments is ~ 5.0 × 10−1 for 1 GHz frequency resolution [280]. Dual THz comb systems achieve much higher frequency resolution with lower sensitivities [154, 251]. This is due to the longer delay times needed to resolve individual comb teeth. Overall, the sensitivity of oscillator-based THz-TDS systems is limited by detector noise.

Compared with broadband spectroscopy in the near-and mid-infrared, THz-TDS is still in its infancy. Initial demonstrations in trace gas sensing, however, highlight some possible future applications of THz-TDS [280–282]. For example, in 2016 Hsieh et al. used ASOPS THz-TDS to measure acetonitrile gas at atmospheric pressure in the presence of smoke from a burned incense stick [280]. Scattering losses from smoke particulates make this a challenging measurement at higher frequencies, but Hsieh et al. reported no measured loss in the longer wavelength THz transmission. At 1 s of integration the detection limit of acetonitrile was 200 ppmv, while they also estimated higher detection limits of HCN (200 ppmv) and SO2 (700 ppmv). While these detection limits are higher than in the near- or mid-infrared, the recent development of plasmonic photoconductive emitters should improve measurement sensitivities by 10–100× [283]. The transmission of THz light through samples opaque in the infrared and visible is also attractive for sensing of concealed explosives, and THz-TDS has been demonstrated as an effective tool for differentiating explosives based on their characteristic vibrational and phonon absorptions [284]. A related application is the non destructive examination of space shuttle tiles with THz-TDS, particularly in corrosion and defect detection [285].

4. FUTURE DIRECTIONS