Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study was to document clinical features of inguinal hernia (IH) in the pediatric population. It provides data to evaluate associated risk factors of incarcerated hernia, its recurrence as well as the occurrence of contralateral metachronous hernia.

Materials and Methods:

We report a retrospective analytic study including 922 children presenting with IH and operated from 2010 to 2013 in our pediatric surgery department.

Results:

We managed 143 girls (16%) and 779 boys (84%). The mean age was 2 years; the right side was predominantly affected (66.8%, n = 616). Incarcerated hernia was documented in 16% of cases with an incidence of 33% in neonates. The incarceration occurrence was 15.5% in males versus 2.09% in females. The surgical repair was done according to Forgue technique. Postoperatively, four cases of hernia recurrence were documented, and contralateral metachronous hernia was reported in 33 children with 7.7% females versus 2.8% males. Forty-five percent of them were infants. The mean follow-up period was 4 years. We think that incarceration can be related to several risk factors such as feminine gender, prematurity, and the initial left side surgical repair of the hernia.

Conclusion:

IH occurs mainly in male infants. Prematurity and male gender were identified as risk factors of incarceration. Contralateral metachronous hernia was reported, especially in female infants and after a left side surgical repair of the hernia.

KEYWORDS: Children, inguinal hernia, recurrence, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Inguinal hernia (IH) is the most common surgical condition of childhood, affecting 1%–2% of mature infants and up to 30% of premature infants.[1]

One of the major complications of IH is incarcerated hernia. The risk of incarceration in children with IH ranges from 3% to 16%, with the highest incidence estimated to be 30% in premature children.[2]

In this study, we reviewed 922 children to assess clinical features of IH in the pediatric population and to evaluate associated risk factors of incarcerated hernia, its recurrence as well as the occurrence of contralateral metachronous hernia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted an analytic retrospective study of children's medical charts with IH managed in the Pediatric Surgery Department from 2010 to 2013.

Data were gathered through a standardized form including age at surgery, hernia side, circumstances of surgery (incarcerated or not incarcerated), postoperative complications, and the occurrence of metachronous hernia. Patients presenting with crural hernia or undescended testis with a surgical repair of a persistent peritoneal-vaginal duct were excluded from the study. Children were managed by herniotomy with direct inguinal approach according to Forgue technique. The so-called Barker artifice was performed in all female infants to repair the round ligament. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel Microsoft office 2013 (codenamed office 15) license trialware, and variables were compared with Chi-squared test.

RESULTS

Descriptive data

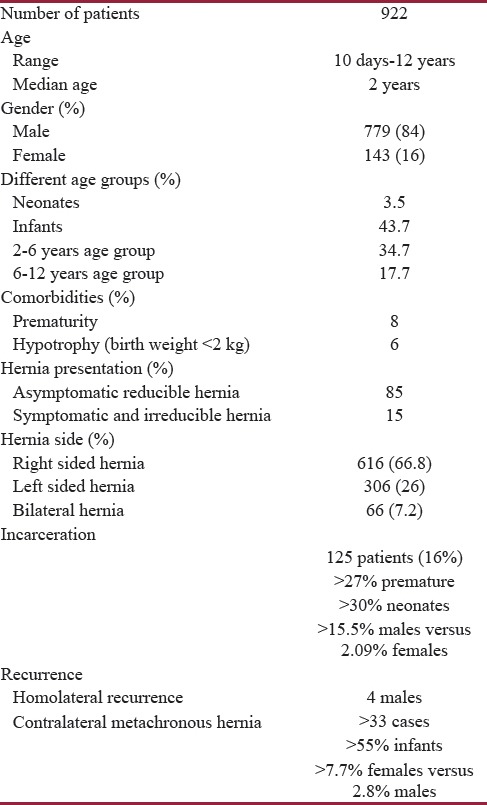

Demographic data of the studied population are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of all patients

Epidemiologic data

The median age in our study group was 2 years (range 10 days to 12 years). Males are predominantly affected (84%, n = 779). The rate of IH was more important in the youngest group (age < 2 years); thus, we accounted 43.7% (n = 403) infants. The cumulative incidence of hernia in the 2–6-year age group was 34.7% (n = 320).

Clinical data

Sixteen percent (n = 125) of these patients presented with an incarceration mainly on the right side (66.8%, n = 616). We identified that the overall rate of incarcerated hernia occurrence in premature group was evaluated at 27%. This rate was high, especially in neonates and infants. Prematurity and hypotrophy were documented, respectively, in 8% and 6%.

Surgical management

Uncomplicated IH was managed with an elective surgical repair. Once diagnosed, timing of herniotomy for asymptomatic hernia ranged from 1 to 5 weeks in our group study.

Regarding infants presenting with incarcerated hernia, a manual attempt of hernia reduction, according to “Taxis technique,” was successfully done in most cases.

Otherwise, after an intrarectal administration of a muscle relaxant drug such as “midazolam” at the dose of 0.3 mg/kg, a gentle precision led subsequently in most cases to hernia reduction.

However, we documented two infants who were presenting initially as an emergency (irreducible hernia), those cases had undertaken an emergency operation. Thus there was an intestinal ischemia, but intestinal resection was not necessary. Patients achieved postoperatively full recovery.

Herniotomy, for incarcerated hernia that could be reduced according to “Taxis,” was performed within 72 h.

All hernia repairs were carried out under general anesthesia. The surgeon was a specialist senior in 543 cases (58.9%) versus a resident in 373 cases (40.5%). The mean operation timing was 21 min (range: 11–140 min).

On surgical exploration, there were particularities in young females; In fact, generally, the hernia sac is freed, and once the surgeon is certain that the sac does not contain any ovarian or intestinal content, it is closed. In our study group, we found an ovarian content in 6%, intestinal content (appendix or intestinal loop) in 2%, bladder corn in 1%, and fallopian tube in 1%. All patients received postoperative pain relief as well as postoperative surgical wound care. The mean follow-up period was 4 years.

Postoperative complication analysis

Postoperative complications were identified. Thus, we reported a postoperative peritonitis, due to bowel perforation, in one child who subsequently required an intestinal resection-anastomosis. The patient recovered well. An abdominal distension with a good spontaneous recovery was also documented in one case.

Postoperative evaluation

We report four cases of recurrence, for unilateral herniotomy within 12 months postoperatively. Recurrence on the opposite side occurred in 33 patients (3.6%). Most of them were female infants who were initially operated on the left side with 7.7% versus 2.8% (in males).

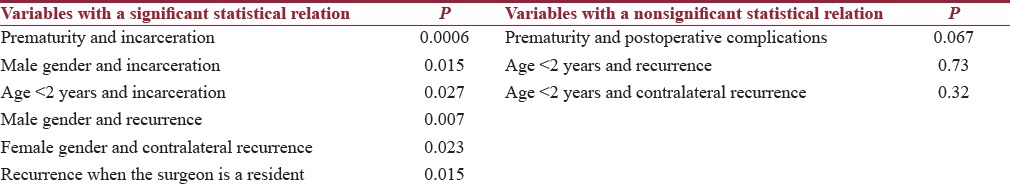

Analytic study

The statistical study is detailed in Table 2. In fact, risk factors of incarceration identified in this study are essentially: Prematurity, male gender as well as age <2 years. Hernia recurrence is not related to patient age, recurrence on the operated side is much more observed in males, and we noted a significant statistical relation between recurrence and trainee surgeons (P = 0.015). Thus, cases of recurrence were noted essentially when the surgeon is a resident. However, risk of hernia recurrence on the opposite side is significantly high in females and was not age specific. We found that the statistical relation between prematurity and postoperative complications was not significant with P = 0.067.

Table 2.

Statistical relations between variables studied

DISCUSSION

From this study, the cumulative incidence of IH was 11%, and this rate is higher than that quoted in the literature with an incidence of approximately 0.8%–4.4%.[3,4]

The male-to-female ratio of 5/1 noted in this article agrees with that reported in the literature (3/1–10/1) as does the higher incidence of right-sided occurrence.[3]

The median age in our study group was 2 years (range 10 days to 12 years). Most of the hernias in this series occurred in the younger patients; thus, the incidence of IH was more important in the youngest group (age <2 years), i.e., 43.7% and decreases as children age.

Otherwise, in pediatrics survey and according to Nataraja and Mahomed[5] and Ron et al.,[6] the hernia occurrence in children is closely related to age and the risk is particularly increased in children under 2 years of age.

Published data documented that levels of prematurity and dysmaturity were included among potential risk factors of IH.[7,8] In fact, prematurity in our study was evaluated at 8%. The evidence for the optimal management of IH in premature infants was not well established in our department. In these fragile newborns, we believed that surgical repair might expose them to high risk of perioperative and postoperative complications. Therefore, in our procedure, we were reluctant toward avoidable emergency operations to minimize potential surgical and anesthetic complications. That made us adopt elective surgical repair.

Reported survey data described the eventual minor risk of IH development in females as compared to males with an incidence of 1.9%.[8] In the current study, we reported an incidence of 16% versus 84% in males.

Once IH diagnosis in a female is made, repair should be carried out promptly because incarceration occurs in the 1st year of life. Reduction of an incarcerated ovary is not as urgent as a reduction of incarcerated intestinal loop, but still, it should be done at the earliest.[8] Bilateral exploration in all female patients has been recommended by some authors. However, routine contralateral exploration is felt unjustified since only 10% of children with unilateral repair subsequently developed a contralateral hernia.[9] In this series, any contralateral herniotomy was systematically done.

Incarceration occurred in 12% at a mean age of 1.5 years, mostly in boys and mostly on the right side.[3] The occurrence of complicated IH has been documented in about 30% of cases in the age group under 2 months.[10]

Stylianos et al.[11] aimed to assess the incidence of incarcerated IH in their series and they concluded that 85% of incarceration occurred before the 1st birthday.

Nonetheless, our analysis demonstrated that complication occurred in 125 patients (16%), about one-third of strangulation were noted in children under 1 year old, 27% were premature. We also reported that the risk of incarceration decreased with age.

For this group of patients, we attempted a manual reduction; it led generally to the hernia reduction. Herniotomy was then carried out within 72 h.

As described in the literature, for children who presented with incarcerated hernia, early surgical intervention is indicated due to high re-incarceration rates.[2]

Reports exist with regard to the association between prematurity and incarcerated IH. Our results found a significantly higher rate of incarcerated hernia in premature children (with significative P value).

These findings were compatible with early reports which revealed that incarceration was mostly encountered in preterm infants with a relatively high rate of 30%.[2]

In fact, Erdogan et al.[12] found that the incidence rate of hernia strangulation in premature children was 9.6% versus 5.9% in full-term children.

According to Canadian Paediatric Surgeons Guideline,[13] there were recommendations for optimal timing of surgical hernia repair. It was demonstrated that surgical management should be performed 1 week after the diagnosis. Otherwise, several studies reported that the risk of incarceration doubles after a prolonged delay.[14]

Decision concerning the suitable timing of IH repair in fragile pediatric population should be particularly well considered. In fact, surgeons have to balance surgical complications associated with earlier management with the potential for hernia incarceration if repair is delayed. Thus, the risk of hernia incarceration in patients admitted for delayed repair has been demonstrated to be between 0% and 41%, while the need for postoperative respiratory support following early repair has been reported to be as high as 38%.[8,14]

In addition to that, current guidelines from the Committee on Fetus and Newborn and the Section on Surgery of the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded that a prompt management of IH in such vulnerable population should be considered against the risk of postoperative complications.[15] In our study, age was not significantly related to postoperative complications.

The trend to a higher incidence of metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia (MCIH) in female patients in our review (7.7% vs. 2.8%) is in accordance with Ron et al.[6] as well as with Nataraja and Mahomed[5] Steven et al.[16] found a moderate rate of metachronous hernia (14%).

Kalantari et al.'s study[17] shows similar results with 10% of metachronous contralateral hernia.

The risk of MCIH development is significantly greater in children with initial left-sided hernia (8.5% vs. 3.3%). Further risk factors may well include female gender (8.2 vs. 4.1%) and young age (<1 year) (6.9% vs. 4.5%).[18]

Although our series showed that a girl with an hernia on the left side had 7% chance of developing an opposite-side hernia on her right side (which was not age related), the fact that 7.7% of girls ever developed an opposite side hernia lead us to conclude that routine contralateral exploration is not indicated. Much controversy about controlateral exploration continues to exist from many authors.[3]

The recurrence rate in our series was 0.4%, and it occurred within 12 months postoperatively. It was documented, especially in cases that were managed by a resident and not a senior surgeon.

Our recurrence rate falls between other reports in the literature of 0% and 3.8%.[3] We believe that recurrences occurred because of the dissolvable suture used for the high ligation of the sac which dissolved early or because of the sac being completely missed, incompletely repaired, or not being ligated high enough.

Recently, some authors adopted a laparoscopic approach as an alternative to the open procedure. Laparoscopic repair provides an excellent visual exposure. It is able to allow better evaluation of the contralateral side as well as minimal dissection to avoid vas deferens and spermatic vessels, bladder injuries, and iatrogenic ascent of the testis. In addition, the well-known excellent cosmetic results of this approach encourage authors to apply this technique widely in pediatrics.[19]

Furthermore, transinguinal laparoscopic exploration can be used for identification of contralateral IHs in pediatric patients; this method proved to be safe and efficient that some surgeons recommend to use it routinely.[20]

The present work has several strengths. First, the nationwide database comprises a relatively huge population; there are also several limitations. Our data only included participants who were covered in our hospital; nonetheless, we believe that the data are reliable because the coverage rate of our hospital is almost 60% of the population. However, the exact number of undiagnosed and untreated patients is unknown.

CONCLUSION

IH occurs mostly in boys <2 years old. Prematurity and hypotrophy are described as risk factors of IH. Premature boys should be promptly managed because of the high risk of incarceration. Metachronous IH occurs essentially in females; thus, laparoscopic approach can be helpful to detect contralateral hernia with better cosmetic results. We recommend also that the resident should be assisted by a senior to avoid postoperative complications such as hernia recurrence.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education, research laboratory: LR12SP13.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Timberlake MD, Herbst KW, Rasmussen S, Corbett ST. Laparoscopic percutaneous inguinal hernia repair in children: Review of technique and comparison with open surgery. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11:262.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang SJ, Chen JY, Hsu CK, Chuang FC, Yang SS. The incidence of inguinal hernia and associated risk factors of incarceration in pediatric inguinal hernia: A nation-wide longitudinal population-based study. Hernia. 2015;30:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ein SH, Njere I, Ein A. Six thousand three hundred sixty-one pediatric inguinal hernias: A 35-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:980–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan ML, Chang WP, Lee HC, Tsai HL, Liu CS, Liou DM, et al. A longitudinal cohort study of incidence rates of inguinal hernia repair in 0 to 6 year-old children. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:2327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nataraja RM, Mahomed AA. Systematic review for paediatric metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia: A decreasing concern. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011;27:953–61. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2919-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ron O, Eaton S, Pierro A. Systematic review of the risk of developing a metachronous contralateral inguinal hernia in children. Br J Surg. 2007;94:804–11. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Goede B, Verhelst J, van Kempen BJ, Baartmans MG, Langeveld HR, Halm JA, et al. Very low birth weight is an independent risk factor for emergency surgery in premature infants with inguinal hernia. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SL, Gleason JM, Sydorak RM. A critical review of premature infants with inguinal hernias: Optimal timing of repair, incarceration risk, and postoperative apnea. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:217–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla S. Inguinal hernia in females. Med J Armed Forces India. 2001;57:306–8. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(01)80009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aboagye J, Goldstein SD, Salazar JH, Papandria D, Okoye MT, Al-Omar K, et al. Age at presentation of common pediatric surgical conditions: Reexamining dogma. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:995–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stylianos S, Jacir NN, Harris BH. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:582–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90665-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erdogan D, Karaman I, Aslan MK, Karaman A, Cavusoglu YH. Analysis of 3,776 pediatric inguinal hernia and hydrocele cases in a tertiary center. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1767–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gawad N, Davies DA, Langer JC. Determinants of wait time for infant inguinal hernia repair in a Canadian children's hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:766–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sulkowski JP, Cooper JN, Duggan EM, Balci O, Anandalwar SP, Blakely ML, et al. Does timing of neonatal inguinal hernia repair affect outcomes? J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang KS. Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics. Assessment and management of inguinal hernia in infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:768–73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steven M, Greene O, Nelson A, Brindley N. Contralateral inguinal exploration in premature neonates: Is it necessary? Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:703–6. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalantari M, Shirgir S, Ahmadi J, Zanjani A, Soltani AE. Inguinal hernia and occurrence on the other side: A prospective analysis in Iran. Hernia. 2009;13:41–3. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0411-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenk K, Sick B, Sasse T, Moehrlen U, Meuli M, Vuille-dit-Bille RN. Incidence of metachronous contralateral inguinal hernias in children following unilateral repair – A meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:2147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shalaby R, Ismail M, Samaha A, Yehya A, Ibrahem R, Gouda S, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair; experience with 874 children. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:460–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazar DA, Lee TC, Almulhim SI, Pinsky JR, Fitch M, Brandt ML. Transinguinal laparoscopic exploration for identification of contralateral inguinal hernias in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:2349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]