Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

In response to the reviewers comments, we modified figure 5 and 6 (error bars, size bars have been added). We also provide more information regarding the in vivo experiments and tuned down the interpretation regarding virulence of mic2KO parasites. Furthermore, supplementary information for the RNAseq analysis has been added. New data added: RH FPKM, MIC2 KO FPKM and AMA1 FPKM, contain the FPKM of the three triplicates for all Toxoplasma genes for RH, mic2 KO and ama1 KO strains. MIC2KO-RH and AMA1KO-RH total results obtained after Cutdiff analysis between RH and mutants. The addition of these data will allow to access the whole RNA sequencing results and perform independent analysis.

Abstract

Background: Micronemal proteins of the thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) family are believed to play essential roles during gliding motility and host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites, and currently represent major vaccine candidates against Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria. However, recent evidence suggests that they play multiple and different roles than previously assumed. Here, we analyse a null mutant for MIC2, the TRAP homolog in Toxoplasma gondii. Methods: We performed a careful analysis of parasite motility in a 3D-environment, attachment under shear stress conditions, host cell invasion and in vivo virulence. Results: We verified the role of MIC2 in efficient surface attachment, but were unable to identify any direct function of MIC2 in sustaining gliding motility or host cell invasion once initiated. Furthermore, we find that deletion of mic2 causes a slightly delayed infection in vivo, leading only to mild attenuation of virulence; like with wildtype parasites, inoculation with even low numbers of mic2 KO parasites causes lethal disease in mice. However, deletion of mic2 causes delayed host cell egress in vitro, possibly via disrupted signal transduction pathways. Conclusions: We confirm a critical role of MIC2 in parasite attachment to the surface, leading to reduced parasite motility and host cell invasion. However, MIC2 appears to not be critical for gliding motility or host cell invasion, since parasite speed during these processes is unaffected. Furthermore, deletion of MIC2 leads only to slight attenuation of the parasite.

Keywords: Toxoplasma, Microneme, Gliding motility, Host cell invasion, TRAP, MIC2, Plasmodium

Introduction

Apicomplexan parasites are obligate intracellular parasites that invade the host cell in an active process that involves the parasite’s own acto-myosin system acting in concert with parasite-derived surface ligands ( Meissner et al., 2013). These ligands are derived from secretory organelles, the micronemes, which are unique to apicomplexan parasites. Indeed, microneme secretion has been demonstrated in several studies to be linked to efficient parasite invasion and gliding motility, and it has been suggested that micronemal proteins act as force transmitters for the acto-myosin system, similar to the role of integrins in amoeboid cells ( Bargieri et al., 2014; Tardieux & Baum, 2016). These proteins are then cleaved by rhomboid proteases (ROMs) to release the force ( Rugarabamu et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2014a).

One crucial family of micronemal proteins is the thrombospondin-related proteins, such as TRAP, MTRAP, TSP and CTRP, which have been suggested to be essential for gliding motility and invasion in diverse life stages of Plasmodium spp. ( Bartholdson et al., 2012; Baum et al., 2006; Dessens et al., 1999; Morahan et al., 2009; Moreira et al., 2008; Sultan et al., 1997). Similarly, the Toxoplasma gondii homolog of TRAP, MIC2, is thought to be required for gliding motility and invasion, and a conditional knockdown mutant for mic2 suggested that MIC2 is an important component of this machinery ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). However, recent results questioned the importance of MIC2, since it is relatively straightforward to obtain clonal mic2 null mutants using reverse genetic tools, such as a conditional recombinase system ( Andenmatten et al., 2013). Furthermore, a recent genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screen indicated a relatively minor contribution of mic2 to parasite fitness in vitro ( Sidik et al., 2016). Given the huge repertoire of micronemal proteins, it is thus tempting to speculate that multiple redundancies exist among these proteins. Such a situation has been described for AMA1, a micronemal protein that is involved in host cell invasion, but is not essential ( Bargieri et al., 2013; Lamarque et al., 2014).

A recent systematic dissection of other proteins involved in gliding motility, such as parasite actin, myosin A and its light chain MLC1, GAP45 and GAP40 has identified novel functions for these proteins and demonstrated that the gliding machinery is involved in the formation and release of attachment sites ( Bargieri et al., 2014; Egarter et al., 2014a; Harding et al., 2016; Periz et al., 2016; Whitelaw et al., 2017). Furthermore, MIC2 is thought to interact with parasite F-actin via a connector protein that has been recently described and suggested to bind both the cytosolic tail of MIC2 and parasite F-actin ( Jacot et al., 2016), which might well be involved in the regulation of attachment sites.

Given our evolving understanding of parasite motility mechanisms, we set out to re-analyse the functions of mic2 during the parasite’s asexual life cycle, both in vitro and in vivo. We confirm previous findings, demonstrating that MIC2 is involved in gliding motility and invasion ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). This involvement is best demonstrated in attachment assays that suggest an important role for MIC2 in the generation of attachment sites that are required for efficient motility. However, while mic2KO parasites exhibited less motility and move on shorter distance, they reach the same maximal speeds as WT parasites. Similarly, fewer parasites lacking MIC2 invade host cells, but when they do invade they do so at speeds comparable to WT parasites. Like parasites deficient in other components of the acto-myosin system, with which MIC2 interacts, the mic2 KO parasites show delayed host cell egress. Mice have been widely use and an in vivo model of toxoplasmosis to test virulence of T. gondii in mammalian hosts. Unexpectedly, in vivo analysis demonstrates that they are only mildly attenuated and still induce lethal disease in mice. RNA sequencing analysis revealed that deletion of mic2 has a minor impact on the transcription levels of other micronemal, ROMs and motor complex proteins, as well as several proteins with no obvious connection to invasion or motility, suggesting a multifactorial adaptation to loss of MIC2.

Results

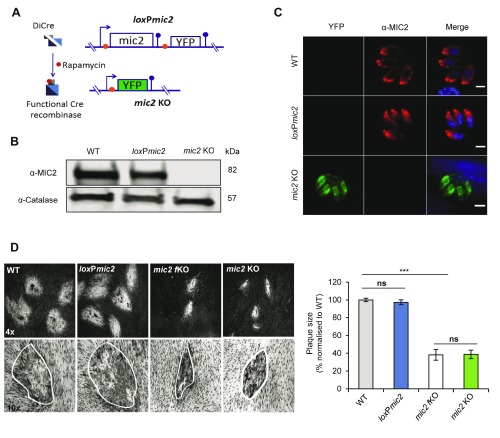

mic2 is an important but non-essential gene

We previously described the generation and initial characterisation of a null mutant for mic2 using the DiCre system ( Andenmatten et al., 2013). In this mutant, the native mic2 gene has been replaced by loxP-flanked mic2 cDNA ( loxP mic2). Upon Cre-mediated site-specific recombination, the mic2 cDNA was removed, and the reporter gene YFP placed under the control of the endogenous promoter, resulting in green fluorescent mic2 KO parasites ( Figures 1 A–C). Despite forming smaller plaques when compared to the WT RH strain, mic2 KO parasites can be easily isolated and maintained in culture, demonstrating that mic2 is an important, but non-essential gene in the Toxoplasma lytic cycle, as described previously ( Andenmatten et al., 2013). No significant differences in plaque size were observed between loxP mic2 and WT T. gondii parasites ( Figure 1D). To address the possibility of adaptation to mic2 loss, we compared freshly induced mic2 KO (1 lytic cycle, mic2 FKO) to mic2 KO parasites cultured for more than one year after induction. No significant difference in plaque size was observed between the two strains ( Figure 1D). Proteolytic processing and trafficking of the MIC2-associated protein (M2AP) was previously shown to depend on MIC2 ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). We confirmed that depletion of MIC2 leads to M2AP mislocalisation and constitutive secretion of unprocessed M2AP ( Figure S1) with no significant effects on the localisation or secretion of other tested micronemal proteins.

Figure 1. Generation of a mic2KO clonal line using DiCre recombinase system.

A) Schematic representation of the construct used for generating mic2 KO parasites. The endogenous mic2 was replaced by mic2 cDNA flanked with loxP sites (orange circles). Upon addition of rapamycin, the gene was excised and YFP expressed. Stop codons are represented by blue circles. B) Immunoblot analysis of MIC2 expression in WT, loxP mic2 and mic2 KO parasites. Catalase was used as a loading control. C) IFA of MIC2 and YFP expression in WT, loxP mic2 and mic2 KO parasites. Scale bars: 2 µm. n=6, total number of vacuoles observed >450. D) Representative examples and analysis of plaque assays comparing WT, loxP mic2, mic2 FKO and mic2 KO. *** p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student's t-test.

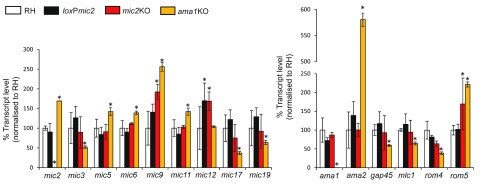

Deletion of mic2 leads to only minor changes in the expression of other known invasion machinery components

In the case of ama1, the removal of the gene leads to the upregulation of its homologue ama2, allowing compensation of the loss of ama1 function ( Bargieri et al., 2013; Lamarque et al., 2014). To test if removal of mic2 leads to up- or downregulation of known components of the invasion machinery (i.e. other micronemal or glideosome proteins, actin, etc.), RNA sequencing analysis was performed to compare relative gene expression levels in RH, loxP mic2, mic2 KO and ama1 KO. RH was used as a reference (100%) ( Figure 2, Figure S2). In parallel, we confirmed for ama1 KO that transcription levels of ama2 were upregulated. We also observed increased transcription levels of various other genes in ama1 KO that are implicated in invasion, such as mic2, mic5, mic6, mic9, mic11, and rom5, as well as downregulation of mic3, mic17a, mic19, gap45, mlc1 and rom4, suggesting that adaptation to ama1 disruption in culture is multifactorial. Although ama2 shows the strongest upregulation, the overall expression level of ama2 remains very low compared to ama1 ( Figure S2, Table S1).

Figure 2. Transcriptional analysis of MIC expression levels in the mic2 KO parasites.

Graphical representation of percentage of mean FPKM value normalised to RH value for RH (White), loxP mic2 (Black), mic2 KO (Red) and ama1KO (Yellow) strains. Differences between each mutant and RH were calculated using CutDiff with a comparison of three independent biological replicates, using the quartile library normalization method, a “pooled” dispersion estimation method with the three replicates and a false discovery rate of 0.05. Statistically significant differences from RH are indicated by *. Error bars indicate the FPKM standard deviation within the replicate.

Fewer differences were seen between loxP mic2 and mic2 KO parasites than were seen in ama1 KO ( Figure S2, Table S1). Other than mic9 and rom5, deletion of mic2 had little effect on the transcription level of the known MICs, glideosome or rhomboid genes examined. Furthermore, when we compared the whole transcriptomes, we observed similar changes in ama1 KO and mic2 KO, suggesting a potential multifactorial and overlapping adaptation process. The genes whose expression changed include several proteases, surface antigens and hypothetical proteins ( Table S2 and Table S3). However, based on this analysis we were unable to identify a clear candidate that could compensate for los of mic2.

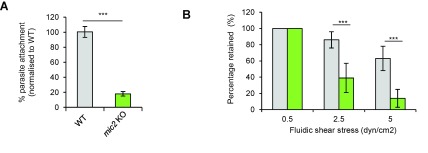

Attachment is impaired in mic2 KO parasites

We previously demonstrated that the acto-myosin system of the parasite is important for surface attachment and required for efficient initiation of gliding motility ( Whitelaw et al., 2017). Since MIC2 is connected to this system, we wished to investigate if a similar phenotype can be observed in mic2 KO parasites. Using a standard attachment assay ( Whitelaw et al., 2017), we observed that the percentage of mic2 KO parasites attached to host cells dropped to 20% in comparison to WT ( Figure 3A), consistent with previous studies ( Harker et al., 2014; Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). We also estimated attachment strength using a fluidic shear stress assay on surfaces coated with collagen IV ( Figure 3B). Parasites were incubated without flow to allow them to attach to the surface. An initial flow of 0.5 dyn/cm 2 was applied to wash off unattached parasites and the remaining number of parasites for each strain was considered as the initial value (100%). In contrast to control parasites, mic2 KO parasites were washed off rapidly at low shear stress (39% vs. 86.6% parasites remaining for mic2 KO and WT, respectively at 2.5 dyn/cm 2), consistent with previous results using the mic2 conditional knockdown ( Harker et al., 2014). In summary, mic2 KO parasites have a deficiency in their capacity for surface attachment, which will inevitably affect gliding motility and host cell invasion.

Figure 3. mic2KO parasites show impaired attachment to host cells and collagen IV.

A) Percentage of parasites attached to host cells after 30 min. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM, *** p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student's t-test. B) Percentage of parasites retained on a collagen IV-coated surface under fluidic shear stress relative to 0.5 dyn/cm 2 flow for RH and mic2 KO. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM, *** p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student's t-test.

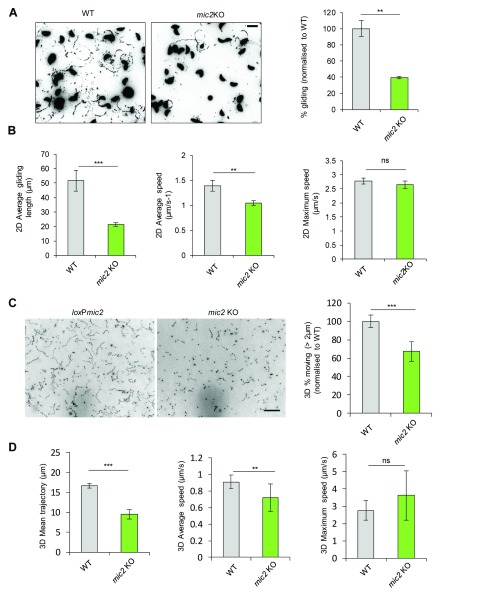

Depletion of MIC2 has little impact on gliding speed

To analyse the role of MIC2 during gliding motility, we performed standard trail assays to determine the ratio of gliding to immotile parasites. Using this analysis, we confirmed that the majority (~60%) of mic2 KO parasites are incapable of initiating gliding compared to WT ( Figure 4A), as previously reported ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). By video microscopy, the three types of motility (circular, helical and twirling) ( Håkansson et al., 1999) were observed ( Video S1– Video S6). Time lapse analysis showed that once motility was initiated, depletion of MIC2 has an effect on both the average speed and average distance travelled by helically gliding parasites, while the maximal speed was not affected ( Figure 4B). In the case of circularly gliding parasites, a reduction in the average distance travelled was seen for mic2 KO parasites, consistent with previous data ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). Surprisingly, the average and maximum speeds of circular gliding increased compared to WT parasites ( Figure S3).

Next, we wished to investigate gliding motility in a more physiological 3D environment ( Figure 4C). In good agreement with the 2D-motility assays, fewer mic2 KO parasites initiated motility in a 3D matrix when compared to WT parasites. Furthermore, a significant reduction in average displacement (9.54 ± 1.17 µm vs. 16.66 ± 0.58 µm) and average speed (0.72 ± 0.16µm/s -1 vs. 0.91 ± 0.08 µm/s -1) was observed in mic2 KO vs. WT parasites, respectively ( Figure 4D). Again, no reduction in maximal speed was observed, indicating an “all-or-nothing” response ( Figure 4D). Together, these data suggest that, similar to MyoA, MLC1 and F-Actin, the predominant function of MIC2 is in the establishment of attachment sites required for effective initiation of motility.

Figure 4. Gliding initiation and gliding distance are affected by mic2 KO attachment defect but not maximal speed.

A) Trail deposition assay of WT parasites compared to mic2 KO. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM and ** p-value <0.01 in a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Scale bar 5 μm B) Kinetic analysis of 2D helical gliding. Data were analysed using auto-tracking software. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM, ***: p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student’s t-test. C) Representative maximum intensity projections of 3D Matrigel-based motility assays comparing WT to mic2 KO parasites (left) and % of parasites moving (right) normalised to WT. Scale bar 50 μm D) Analysis of 3D trajectories; mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SD, ***: p-value <0.001 in two-way Anova with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

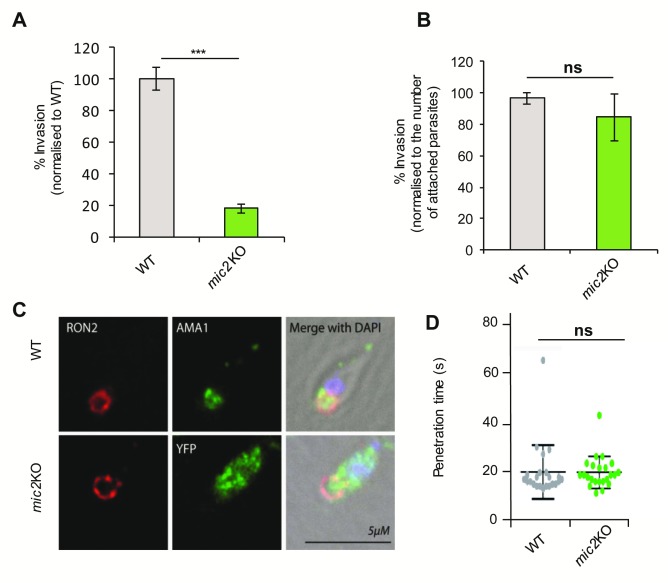

Depletion of MIC2 results in lower invasion rates, but has no influence on invasion speed

Next, we investigated the invasion process of mic2 KO parasites ( Figure 5A) and found, as previously described ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006), that invasion is strongly inhibited, at 18 ± 3% relative to WT invasion levels. In this assay the overall failure of invasion is measured, which could be due to defects in host cell attachment, junction formation or host cell penetration. To differentiate between these individual steps, invasion rates were normalized to the total number of interacting parasites ( i.e., attached plus invaded). Interestingly, in this case the invasion rates of WT and mic2 KO parasites are similar, demonstrating that the reduced invasion of mic2 KO parasites relative to WT parasites is mainly due to their failure to attach to the host cell ( Figure 5B). Next, we assessed junction formation and penetration speeds ( Figures 5C and D) and were unable to detect significant differences between WT and mic2 KO parasites. mic2 KO parasites invaded through a normal junction and penetrated the host cell at speeds similar to those of WT parasites (21.3 ± 11.7 s and 21.0 ± 6.9 s for WT and mic2 KO, respectively) ( Video S7 and Video S8). These results lead us to conclude that the invasion deficiency observed for mic2 KO parasites is due to impaired attachment to the host cell, as suggested previously ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006).

Figure 5. The mic2 KO defect in invasion is due to diminished attachment capacity.

A) mic2 KO and WT parasites were incubated for 1h with HFF cells, and invasion rate was calculated by comparing the number of mic2 KO vs. WT parasites invaded. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM, ***: p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student's t-test. B) Normalised invasion assays. For each strain ( mic2 KO and WT), the number of invaded parasites was normalized to the total number of parasites observed (attached + invaded). Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM. C) IFA of the junction protein RON2 and AMA1/YFP in mic2 KO and WT tachyzoites, scale bar 5 μm. n=3, total number of parasites observed >50. D) Penetration kinetics of mic2 KO and WT tachyzoites determined by time-lapse microscopy (n=25).

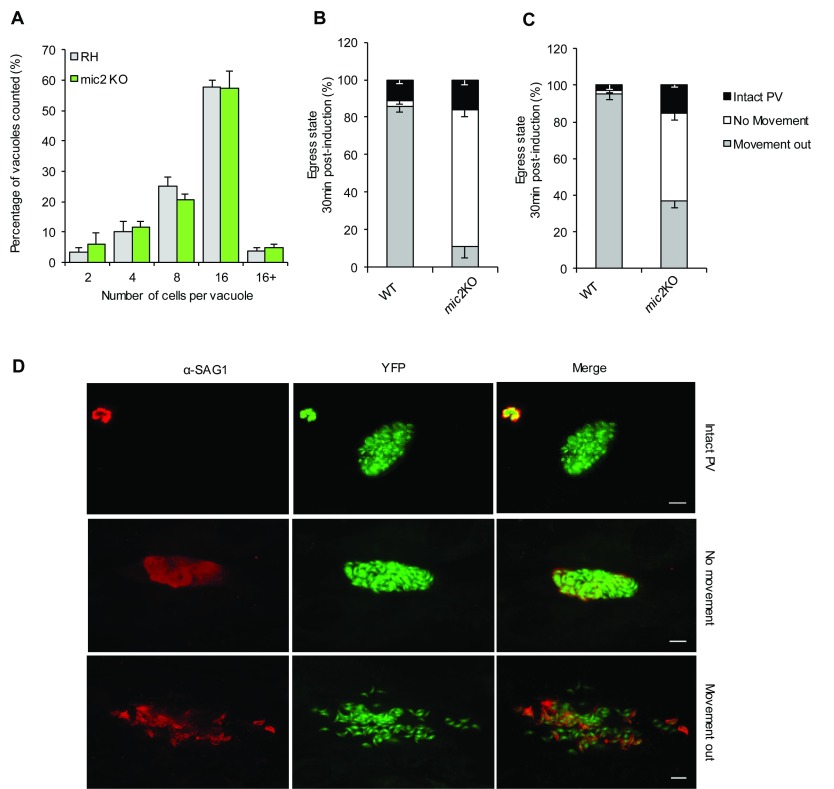

Effect of mic2 deletion on intracellular parasites

We also readdressed the function of MIC2 in intracellular development and egress. While intracellular replication of mic2 KO parasites appeared normal ( Figure 6A), disruption of mic2 caused a significant delay in host cell egress ( Figure 6B–D). When egress was artificially triggered with a Ca 2+ ionophore (A23187), mic2 KO parasites were able to rupture the parasitophorous vacuole at levels comparable to WT (89 ± 2 % vs. 84 ± 5% for WT and mic2 KO respectively) ( Figure 6B). However, a higher proportion of mic2 KO parasites were unable to leave the host cell after lysing the parasitophorous vacuole membrane, suggesting a defect in initiating motility ( Figure 6C and D, and Video S9– Video S10). This defect was still evident even at 30 min after induction, as only 37 ± 3 % of mic2 KO had moved out of the vacuole compared to 95 ± 3 % for WT.

Figure 6. Parasites lacking MIC2 replicate normally, but are defective in host cell egress.

A) Replication analysis of mic2 KO parasites. Parasites were allowed to invade for 1 h prior to intracellular growth for 24 h and the number of parasites per parasitophorous vacuole was counted. Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM. B and C) Parasite egress was artificially induced with Ca2+ ionophore (A23187) for 10 ( B) and 30 min ( C). For quantification, three outcomes were scored: parasites failed to lyse the vacuole (Intact PV), parasites lysed the vacuole but did not move (No movement) or classical egress (Movement out). Mean values of three independent egress assays are shown ± SEM. D) IFA illustrating a newly lysed vacuole (30 minutes post-induction) where antibody against SAG1 can only access part of the vacuole (top panels) and two fully lysed vacuoles, one showing little to no movement of mic2 KO parasites out of the vacuole (middle) and the other showing normal egress (bottom) Scale bar 5 μm.

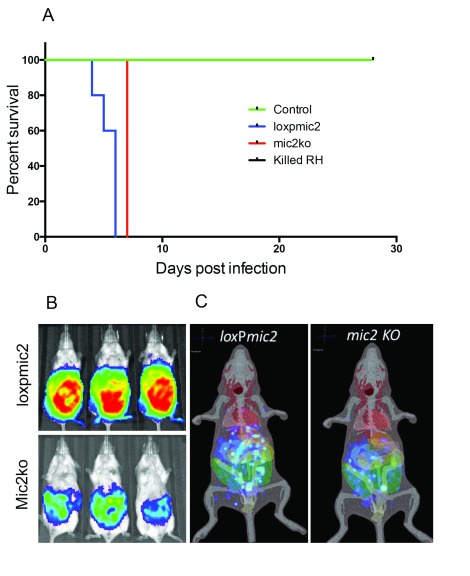

mic2 KO parasites are less virulent than WT parasites but still lethal in mice

Previous data indicated that mic2 knockdown parasites are avirulent in mice ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). To test whether this is also the case for the mic2 KO parasites, mice were infected intraperitoneally with mic2 KO, loxP mic2, killed WT tachyzoites (1×10 4) or PBS. The mic2 KO parasites caused severe disease in mice leading to death or necessitating their euthanasia at humane endpoints by day 7 ( Figure 7A). To verify that the cause of severe disease was due to parasite replication and to allow visualization of parasite burden in real time in vivo, we generated mic2 KO parasites stably expressing a red shift luciferase. Five days post-infection, the mic2 KO parasites were observed at similar anatomical locations, but with a less heavy parasite burden compared to similarly transfected loxP mic2 parasites ( Figures 7B and C).

Figure 7. mic2 KO parasites induce lethal disease in mice and have a similar distribution in infected mice as WT parasites.

A) Mice were infected with 2×10 4 tachyzoites intraperitoneally with PBS, killed T. gondii RH strain or mic2KO RH strain T. gondii and disease followed. Mice infected with the RH strain of T. gondii succumbed to infection by day 7 post infection. B) The localisation of loxP mic2 T. gondii RH strain parasites and mic2 KO T. gondii strain parasites transfected with luciferase were broadly similar at day 5 post infection with parasites evident predominantly in the peritoneal cavity. Heat map represents the intensity of the detected luciferase signal. C) This localisation was supported by 3D diffuse tomographic reconstruction.

Discussion

Gliding motility and host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites have been thought to critically depend on members of the thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) family, which are transmembrane proteins derived from the micronemes ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006; Sultan et al., 1997). A huge body of research on these proteins led to the widely accepted model that they act as a link between the parasite’s cytoskeleton and the host cell by binding to surface receptors with their extracellular domain, and to parasite aldolase, which in turn interacts with parasite actin, via their C-terminal domain ( Jewett & Sibley, 2003; Morahan et al., 2009). Aldolase was recently shown to be dispensable for gliding motility and invasion ( Shen & Sibley, 2014b), but a new “connector” protein postulated to link the tail of MIC2 to actin has been described ( Jacot et al., 2016). Nevertheless, recent re-analysis of TRAP mutants suggested that these proteins do not necessarily function during motility as force transmitters, but rather in the regulated formation and release of adhesion sites ( Hegge et al., 2010; Münter et al., 2009), since Plasmodium sporozoites remain motile in the absence of TRAP or TLP and can be chemically complemented on tuneable substrates ( Hellmann et al., 2013). Furthermore, other members of the TRAP family have been demonstrated to have unexpected functions, unrelated to gliding motility or invasion. For example MTRAP has long been seen as the merozoite specific TRAP homolog that is required for merozoite invasion ( Baum et al., 2006), but recent studies demonstrate that its crucial function lies in gametocyte egress ( Bargieri et al., 2016; Kehrer et al., 2016). Furthermore, reassessment of other components of the gliding machinery in T. gondii, such as actin or MyoA, demonstrated that they play a crucial role in the formation of attachment sites, but not necessarily in force production per se ( Whitelaw et al., 2017), and our current view of the mechanics of this complex system requires further analysis ( Tardieux & Baum, 2016).

In the case of the TRAP-family protein MIC2, previous attempts to knock out the gene failed, suggesting an essential function ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). A conditional knockdown mutant was therefore generated and used to demonstrate important roles for MIC2 in gliding motility, attachment to host cells, host cell invasion and virulence in vivo ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). Using a conditional recombination system, however, we showed that it was possible to generate clonal null mutants for mic2 ( Andenmatten et al., 2013), demonstrating that MIC2 is not an essential gene. This finding was corroborated by a recent genome-wide phenotypic screen based on CRISPR/Cas9, indicating that disruption of mic2 has only a mild phenotypic defect (phenotypic score = -1.17; ( Sidik et al., 2016)).

Here, we assessed the functional consequences of deleting mic2. In contrast to other conditional null mutants generated using the DiCre system, such as the myoA KO, the isolation of clonal mic2 KO mutants was straightforward, indicating only minor competition between non-induced ( mic2 +) parasites and mic2 KO parasites (data not shown). Interestingly, we could not identify any long-term phenotypic adaptation due to prolonged culturing of mic2 KO parasites, since the phenotypes appear to remain unchanged over time. When we performed a comparative transcriptomic analysis, we found that deletion of mic2 had little effect on the transcription level of known MICs, motor or ROM proteins, while multiple proteases (lipases, methionine aminopeptidase), an uncharacterized EGF and PAN domain containing protein, SAG-related proteins and hypothetical proteins were found to be slightly upregulated in the mic2 KO ( Table S2). These data suggest that the deletion of mic2 may result in a multifactorial adaptation that involves small differences in expression levels of seemingly unrelated genes. How rapidly such an adaptation occurs is not known; it is possible that the presence of other microneme proteins with partially overlapping functions immediately enables the parasite to tolerate the loss of mic2. Intriguingly, many of the seemingly unrelated genes upregulated in mic2 KO were also upregulated in ama1 KO ( Table S2 and Table S3).

Like the parasites depleted of MIC2 by conditional knockdown ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006), mic2 KO parasites showed no defect in the trafficking and localization of other microneme proteins (with the notable exception of M2AP) and no effect on intracellular replication, but dramatic effects on host cell invasion, which are due primarily to decreased attachment. Both the conditional knockdown and the KO showed that the loss of MIC2 results in reduced 2D motility, likely through an effect on attachment, and that helical motility is more affected than circular motility. We have extended the motility analysis and shown that in both 2D and 3D, the defect appears to be one of motility initiation; once mic2 KO parasites start moving, they can reach the same maximal speeds as WT parasites. Interestingly a recent study compared adhesion of mic2 knockdown parasites under fluidic stress and concluded that only initial attachment, but not strengthening of attachment sites was affected ( Harker et al., 2014). The invasion phenotype of the mic2 KO is similar to that of ama1 KO parasites, which also show reduced attachment to host cells, but penetration into the host cell at speeds similar to that of WT parasites ( Bargieri et al., 2013). It remains to be seen if redundant proteins can compensate for gliding/invasion motility, but NOT attachment in the absence of MIC2, as suggested for AMA1 ( Lamarque et al., 2014).

In contrast to the MIC2 conditional knockdowns ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006), we find that mic2 KO parasites have a significant delay in host cell egress. The reduced egress is not likely due to a complete inability of the parasite to move, since kinetic analysis of mic2 KO parasites demonstrates only partial motility defects in a 2D and 3D environment. Rather it appears that motility is initiated with a significant delay, and that the parasites stay connected to each other (data not visualised). Future experiments will be required to elucidate the role of MIC2 during egress in more detail and to determine whether the reduced ability of mic2 KO parasites to egress compared to the conditional knockdowns is due to residual expression of MIC2 in the conditional knockdown or to some other effect.

Most surprisingly, and in contrast to the results obtained for the MIC2 conditional knockdown ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006), we find that mic2 KO parasites are only mildly attenuated compared to WT RH parasites. The mic2 KO line (at least at the doses used in these studies) induces lethal disease in BALB/c mice. One explanation for the different findings could be that RH TATi ΔHX, the parasite line used to generate a knockdown for mic2 is already severely attenuated due to the expression of the Tet-transactivator. Indeed, in the study by Huynh & Carruthers, 2006, high doses (5 × 10 4 tachyzoites) with RH TATi ΔHX were required to achieve normal time-to-death kinetics. It is thus possible that knockdown of mic2 in this strain reflects an enhancement of the already attenuated phenotype, while depletion in a WT background has only mild effects on parasite virulence. Alternatively, in our studies a reduced virulence of mic2KO parasites is not evident because of the relatively high numbers of tachyzoites used to facilitate in vivo imaging. Consequently to fully compare the virulence LD50 studies would be required. Nonetheless our studies demonstrate unequivocally that MIC2 is not necessary for in vivo infection and lethality in BALB/c mice. In vivo imaging and 3D diffuse tomographic reconstruction of mice infected with MIC2 deficient parasites transfected with a luciferase gene demonstrated that they grow in similar anatomical locations in mice as control parasites. However, dissection and histopathological analyses would be necessary to rule out any potential differences in tissue trophism.

In summary, we find here that MIC2 acts as important, but not essential, attachment factor, and that reduced invasion and gliding rates are due to a decreased ability to initiate rather than to sustain motility. This is similar to the findings for other components of the acto-myosin system, such as actin, MyoA or MLC1, where it appears that formation of adhesion sites is one of the critical functions of this complex machinery ( Whitelaw et al., 2017). Finally, our finding that deletion of mic2 causes only a mild attenuation of virulence in vivo will have implications for future vaccine design.

Materials and methods

Cloning DNA constructs: All primers used in this study were synthesised by Eurofins (UK) and are listed in Table S4. A red shift luciferase (Bruce Branchini, Connecticut College, USA) was amplified using Luc fw/rv primers and cloned under the p5RT70 promoter with a chloramphenicol resistant cassette.

Mic2 inducible KO vector: As previously described ( Andenmatten et al., 2013), to generate loxPMic2loxP-YFP- HX, the mic2 3′ UTR was amplified from genomic DNA using the primer pair 3′ UTR Mic2 fw/rv, and the PCR fragment was cloned into p5RT70loxPKillerRedloxPYFP-HX via SacI. The mic2 ORF (TGME49_201780) was amplified from cDNA using the primers Mic2 ORF fw/rv and was cloned into the parental vector p5RT70loxPKillerRedloxPYFP-HX using EcoRI and PacI. Finally, the mic2 5′ UTR containing the endogenous promoter was amplified from genomic DNA using the primer pair 5′ UTR Mic2 fw/rv and cloned into the final vector using ApaI and EcoRI.

Culturing of parasites and host cells: Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) were grown on TC treated plastics plates and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 mg/ml gentamycin. Parasites were cultured in HFFs and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO 2.

T. gondii transfection and selection: The conditional mic2 knockout strain ( ku80::diCre/endogenous mic2::loxPmic2loxP, referred to here as loxPMic2) was generated as previously described ( Donald et al., 1996) by transfecting 60 μg of the plasmid loxPMic2loxPYFP-HX into the ku80di::Cre parasites to replace the endogenous copy of mic2, and parasites containing stable integration of this construct were selected using xanthine and mycophenolic acid, as previously described ( Donald et al., 1996). The resulting loxPMic2 strain carries only one copy of mic2, which can be excised by adding rapamycin (50 nM in DMSO for 4 h before washout) to generate the mic2 null mutant ( ku80::diCre/mic2 −, referred to here as mic2 KO). The clonal mic2 KO line was isolated by performing serial dilutions on the clonal induced loxPMic2 strain after 4 h induction and subsequent removal of rapamycin. After verification of the integration, protein expression was checked by western blotting using anti-MIC2 and anti-catalase antibodies and IFA using anti-MIC2 antibodies and YFP expression. Red shift luciferase expressing loxP mic2 and mic2 KO were obtained by transfecting a Red-shift luciferase expressing plasmid using random integration. Parasites were then selected for chloramphenicol resistance and luciferase expression.

RNA extraction and sequencing: RH, loxP mic2, mic2 KO and ama1 KO RNA was extracted using the RNeasy ® Mini Kit (Qiagen) in a biological triplicate. Eluate RNA concentration was determined by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). For sequencing, 4ug per sample was sent to NGS Laboratory, Glasgow Polyomics (University of Glasgow, Bearsden, UK). RNA was analysed after polyA library preparation using paired-end with a depth of sequencing of 25M bases on a Next Seq 500 sequencer. Results were analysed on Galaxy server, with software provided ( http://heighliner.cvr.gla.ac.uk/login?redirect=%2F). After trimming, data were aligned to the T. gondii genome using TopHat2. After mapping, differential expression compared to RH was determined using Cutdiff. For each analysis, data for the three biological triplicates were carried out under the same condition ( loxP mic2, mic2 KO, ama1 KO) and compared to the triplicate of RH parasites using a quartile library normalization method, a pooled dispersion estimation method with a false discovery rate of 0.05. Individual FPKM of each sample was also extracted to control the analysis.

Immunofluorescence analysis: IFA was carried out as previously described ( Egarter et al., 2014b). Briefly, parasites were allowed to invade and replicate in a HFF monolayer grown on glass coverslips. The intracellular parasites were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Afterwards coverslips were blocked and permeabilised in 2% BSA and 0.2% Triton X–100 in PBS for 20 min at RT. The staining was performed using the indicated combinations of primary antibodies for 1 h at RT, followed by the incubation with AlexaFluor 350-, AlexaFluor 488-, AlexaFluor 594- or AlexaFluor 633-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000, Invitrogen–Molecular Probes) for another 45 min at RT. For a list of all antibodies used in this study see Table S5.

Western-blot: Freshly egress RH, loxP mic2 and mic2 KO parasites were harvested, filtered and washed before being resuspendend in PBS containing Pierce™ Protease Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA Free (Thermo Scientific) and Triton X-100 0.2%. Western blots were processed using the indicated combination of primary antibodies for 1h at RT, followed by three washes and incubation with IRDye LiCor secondary antibodies (680RD and 800W, 1:20 000) for another hour at RT. Labeled membranes were visualized using Li Cor Odyssey Clx. For a list of all antibodies used in this study see Table S5.

Phenotypic characterisations

Plaque assay: Plaque assays were conducted as described previously ( Egarter et al., 2014b). 1×10 3 parasites were inoculated on a confluent monolayer of HFFs and incubated for 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO 2, after which the HFFs were washed once with PBS and fixed with ice cold MeOH for 20 minutes. HFFs were stained with Giemsa with the plaque area measured using Fiji software version 1.8.0_66 ( https://fiji.sc/). Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

Secretion assays: Microneme secretion was assayed by monitoring the release of MIC2, M2AP and MIC4 into the culture medium, as described previously ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006). Secretion was observed in absence (constitutive secretion) or presence of 2 μM A23187 (induced secretion) at 37°C.

Attachment assay: 1 ×10 6 parasites were allowed to invade a confluent monolayer of HFF cells for 10 min. Cells were washed and fixed with cold 4% PFA (4°C). The total numbers of parasites within 15 fields of view (Objective 40X) were counted and compared between mic2 KO and WT. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

Attachment under fluidic shear stress: Fresh extracellular parasites (4 × 10 5 in total consisting of approximately equal numbers of control and KO) were loaded into collagen IV coated fluidic chambers (Ibidi IB-80192) and allowed to attach at 37°C for 20 minutes. PBS was pumped through the chamber using an “open loop flow” microfluidic pump (KD Scientific Legato 200 syringe pump) system, similar to that described by ( Harker et al., 2014), to control flow rates and generate fluidic shear stress. In our setup, a flow rate of 1 ml/min achieves 3 dyn/cm 2 shear stress at the surface of the channel. Flow at 0.1 ml/min (equivalent to 0.3 dyn/cm 2) was used to remove all non-attached parasites. At each fluidic shear stress level, control and mutant parasites were counted from 5 fields of view per experiment. Parasite count after the 0.1 ml/min wash was taken as 100% of attached parasites. Counts at all other rates of flow were normalised to the 100%. Data collected was analysed using Excel to assess significance of differences between control and mutants using Student’s t-test and further analysed using GraphPad Prism v. 6.01 software to display data as trends. Parasites in the chamber were monitored via a Zeiss Axio Vert.A1 microscope setup with a 40x objective combined with an AxioCam ICm1 camera and Zen capture software. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

Trail deposition assay: Gliding assays were performed as described previously ( Håkansson et al., 1999). Briefly, freshly lysed parasites were allowed to glide on FBS-coated glass slides for 30 min before they were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with α-SAG1 under non-permeabilising conditions. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

2D video motility assay: Time-lapse video microscopy was used to analyse the kinetics over a 2D surface similar as previously described. Briefly a glass-bottom live cell dish (Ibidi μ-dish 35mm-high) was coated in 100% FBS for 2 hours at room temperature. Freshly egressed parasites were added to the dish. Time-lapse videos were taken with a 20X objective at 1 frame per second using a DeltaVision ® Core microscope. Analysis was done using Fiji version 1.8.0_66 with the wrMTrckr version 1.04 tracking plugin ( http://www.phage.dk/plugins/wrmtrck.html). For analysis, 20 parasites were tracked during both helical and circular gliding with the corresponding distance travelled, average and maximum speeds determined. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

3D motility assay: Tachyzoites were prepared and assayed as previously described ( Leung et al., 2014). Three independent biological replicates, each with three technical replicates, were performed. Parameters calculated from 3D motility assays were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, with GraphPad Prism v. 6.01. Where statistically significant, multiplicity adjusted P values for comparisons are indicated with asterisks.

Invasion and replication assay: 5×10 4 freshly lysed parasites were allowed to invade a confluent layer of HFFs for 1 hour. Subsequently, five washing steps were performed for removal of extracellular parasites. Cells were then incubated for a further 24 hours before fixation with 4% PFA. Subsequently, parasites were stained with α-IMC1 antibody.

For invasion, the number of vacuoles in 15 fields of view (Objective 40X) was counted. Invasion rates were normalised to RH Δhxgprt at 100%. For replication, 200 vacuoles were counted for the number of parasites per vacuole. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

Red/Green assay: Classical “red/green” assays were performed as previously described by Huynh & Carruthers, 2006 to determine the percentage of invasion, independent of the attachment defect of mic2 KO. 1 ×10 6 parasites were allowed to invade a confluent monolayer of HFF cells for 1 hour. Extracellular parasites were stained with α-SAG1 under non-permeabilising conditions. For both strains ( mic2 KO and WT) independently of the other, the number of invaded parasites was compared to the total number of parasites observed (attached + invaded), allowing us to mitigate the attachment phenotype of mic2 KO. Mean values of three independent experiments +/- SD were determined.

Junction formation: 1× 10 6 parasites were artificially released from their vacuole and allowed to invade for 10 minutes, after which the media was removed and 4% PFA was added, fixing the parasites mid-penetration. Coverslips were blocked under non-permeabilising conditions and stained for the rhoptry neck protein, RON2, and AMA1.

Penetration time of invading parasites: Freshly egressed parasites were added to a confluent monolayer of HFFs grown on a glass-bottom live cell dish (Ibidi μ-dish 35mm-high). Time-lapse images were taken at 1 image per second using a 40X objective in DIC for both RH Δhxgprt and mic2 KO parasites. For penetration times, 20 invasion events were analysed and scored from the initial start point of a visible junction to complete parasite internalisation.

Egress assay: Egress assays were performed as previously described ( Black et al., 2000). Briefly, 5×10 4 parasites were grown on HFF monolayers for 36 hours. Media was exchanged for pre–warmed, serum–free DMEM supplemented with 2 µM A23187 (in DMSO) to artificially induce egress. After 5 minutes the cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with anti-SAG1 antibody without detergent permeabilization. 200 vacuoles were counted for parasite egress. Mean values of three independent assays +/- SEM were determined.

In vivo infection model

All animal procedures conformed to guidelines from The Home Office of the UK Government under the Animals [Scientific Procedures] Act 1986. All work was covered by Licence PPL60/3929, “Mechanism of control of parasite infection” with approval by the University of Strathclyde ethical review board. BALB/c mice were bred in house at the Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, Glasgow, UK under specific pathogen free conditions. Mice were housed in polypropylene cages (13cm×35cm), containing Ecopure flakes and sizzle nest bedding (SDS Services) with access to water and CRM mouse chow (SDS Services) ad libatim. Care was taken to minimise suffering through provision of water soaked mouse chow. The minimum number of mice were used to give reliable qualitative results. Six to eight week old female mice (13.4–17.6g, mean 16.1g), grouped in cages of five, were used for infection studies. Mice were assigned randomly to groups by an independent worker with no knowledge of their experimental purpose. Prior to infection, all mice were weighed and subsequently monitored daily for morbidity and weight loss. Mice were euthanised when they reached the humane endpoints set out in the licence.

In initial phenotype studies, groups of five mice were each infected with 2×10 4 WT or loxP mic2 control or mic2 KO tachyzoites in 200μl sterile PBS via intraperitoneal injection (IP). In vivo parasite burden was followed by bioluminescent imaging using loxP mic2 and mic2 KO expressing firefly luciferase. Mice were infected with 2×10 4 tachyzoites via intraperitoneal injection in a volume of 400μl sterile PBS between 10.00–12.00 hrs). For imaging, the mice were dosed with 150mg/kg D-luciferin potassium salt solution (PerkinElmer), anesthetised with isoflurane and imaged (between 10.00 and 12.0 hrs) using an IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer). Isoflurane was used as this is the standard and recommended procedure by PerkinElmer the manufacturer of the IVIS. One minute exposures were taken twenty minutes post luciferin injection. Radiance data were quantified using Living Image software 4.0 (Perkin Elmer) and statistical significance determined by Mann-Whitney test.

Data availability

The data referenced by this article are under copyright with the following copyright statement: Copyright: © 2017 Gras S et al.

Complete Western blots for Figure 1 and Figure S1; raw count for all the assays (Plaque size, Attachment, Invasion, Replication, Egress, Flow, 2D video); raw galaxy results for ama1 KO-RH comparison; raw galaxy results for mic2 KO-RH comparison; raw galaxy results for loxP mic2- mic2 KO comparison are available on OSF: DOI, 10.17605/OSF.IO/FASQG ( Meissner, 2017; https://osf.io/fasqg/).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the Meissner lab for thoughtful discussions. We would also like to thank Prof. Dominque Soldati-Favre (University of Geneva), Prof. Vern Carruthers ( University of Michigan), Dr Maryse Lebrun (University of Montpellier) and Dr Bruce Branchini (Connecticut College) for generously providing antibodies, parasite strains and the luciferase construct. We would like to thank Dr Nicholas Dickens and Dr Mussa Hassan (University of Glasgow) for help with the RNA preparation and sequencing analysis.

Funding Statement

This work was supported the Wellcome Trust [087582], [103875] and [085349]; an European Research Council-Starting grant [ERC-2012-StG 309255-EndoTox] to MM; US Public Health Service [AI105191] and [AI054961] to GW.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; referees: 3 approved]

Supplementary material

Figure S1: Loss of mic2 impacts localization and secretion of M2AP, but not other micronemal proteins. A) Localization by IFA of MIC proteins in mic2 KO and WT tachyzoites; only M2AP localisation is altered. Scale bar: 2 μm. n=3, total number of vacuoles observed >300 B) mic2 KO and WT tachyzoites were incubated in the absence (- ; constitutive secretion) or presence (+ ; induced secretion) of calcium ionophore, and the amount of MIC4 and M2AP secreted into the culture supernatant was determined by western blotting. Actin was used as a loading control. Black arrowhead indicates proM2AP and the empty arrowheads the processed forms ( Huynh & Carruthers, 2006); note that proM2AP is not properly processed in the mic2 KO.

Figure S2: Mean FPKM of MICs in the different KO strains. Graphic representation of the mean FPKM value variation between RH (White), loxP mic2 (Black), mic2KO (Red) and ama1KO (Yellow) strains. The difference between each mutant and RH was calculated using CutDiff with a comparison of three independent biological replicates, using quartile library normalization method, a dispersion estimation method using “pooled” with the tree replicate and a false discovery rate of 0.05. Statistically significant differences are indicated by *. Error bar indicates the FPKM standard deviation within the replicate. MIC5* FPKM value was divided by 2 for graphical purpose.

Figure S3: Kinetic analysis of 2D circular gliding. Kinetic analysis obtained from live records of parasites undergoing circular gliding. Data were analyzed using Analysis was done using Fiji with the wrMTrckr version 1.04 tracking plugin ( http://www.phage.dk/plugins/wrmtrck.html). Mean values of three independent assays are shown ± SEM. ***: p-value <0.001 in a two-tailed Student's t-test.

Supplementary Videos: Representative gliding, invading and egressing parasites. Video S1–S6, mic2 KO and RH parasites making circular, helical and twirling motion; Video S7–S8, mic2 KO and RH parasites invading host cells; Video S9–S10 mic2 KO and RH parasites egressing from host cells. Video were recorded at 1 frame per second.

Supplementary Tables: RNA seq data and primer list. Table S1, RNA sequencing FPKM value of MICs in all strains (RH, loxP mic2, mic2 KO, ama1 KO). Table S2, RNA sequencing Accepted Hits between mic2 KO and RH. Table S3, RNA sequencing Accepted Hits between ama1 KO and RH. Table S4, Primers list used in the study. Table S5, antibodies used in the study. RH FPKM, MIC2 KO FPKM and AMA1 FPKM, contain the FPKM of the three triplicates for all Toxoplasma genes for RH, mic2 KO and ama1 KO strains. MIC2KO-RH and AMA1KO-RH total results obtained after Cutdiff analysis between RH and mutants.

References

- Andenmatten N, Egarter S, Jackson AJ, et al. : Conditional genome engineering in Toxoplasma gondii uncovers alternative invasion mechanisms. Nat Methods. 2013;10(2):125–127. 10.1038/nmeth.2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargieri D, Lagal V, Andenmatten N, et al. : Host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites: the junction conundrum. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(9):e1004273. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargieri DY, Andenmatten N, Lagal V, et al. : Apical membrane antigen 1 mediates apicomplexan parasite attachment but is dispensable for host cell invasion. Nat Commun. 2013;4: 2552. 10.1038/ncomms3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargieri DY, Thiberge S, Tay CL, et al. : Plasmodium Merozoite TRAP Family Protein Is Essential for Vacuole Membrane Disruption and Gamete Egress from Erythrocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(5):618–630. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholdson SJ, Bustamante LY, Crosnier C, et al. : Semaphorin-7A is an erythrocyte receptor for P. falciparum merozoite-specific TRAP homolog, MTRAP. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1003031. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum J, Richard D, Healer J, et al. : A conserved molecular motor drives cell invasion and gliding motility across malaria life cycle stages and other apicomplexan parasites. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(8):5197–5208. 10.1074/jbc.M509807200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MW, Arrizabalaga G, Boothroyd JC: Ionophore-resistant mutants of Toxoplasma gondii reveal host cell permeabilization as an early event in egress. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(24):9399–9408. 10.1128/MCB.20.24.9399-9408.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessens JT, Beetsma AL, Dimopoulos G, et al. : CTRP is essential for mosquito infection by malaria ookinetes. EMBO J. 1999;18(22):6221–6227. 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RG, Carter D, Ullman B, et al. : Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene. Use as a selectable marker for stable transformation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(24):14010–14019. 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egarter S, Andenmatten N, Jackson AJ, et al. : The toxoplasma Acto-MyoA motor complex is important but not essential for gliding motility and host cell invasion. PLoS One. 2014a;9(3):e91819. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egarter S, Andenmatten N, Jackson AJ, et al. : The toxoplasma Acto-MyoA motor complex is important but not essential for gliding motility and host cell invasion. PLoS One. 2014b;9(3):e91819. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson S, Morisaki H, Heuser J, et al. : Time-lapse video microscopy of gliding motility in Toxoplasma gondii reveals a novel, biphasic mechanism of cell locomotion. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(11):3539–3547. 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CR, Egarter S, Gow M, et al. : Gliding Associated Proteins Play Essential Roles during the Formation of the Inner Membrane Complex of Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(2):e1005403. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harker KS, Jivan E, McWhorter FY, et al. : Shear forces enhance Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite motility on vascular endothelium. MBio. 2014;5(2):e01111–01113. 10.1128/mBio.01111-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegge S, Münter S, Steinbüchel M, et al. : Multistep adhesion of Plasmodium sporozoites. FASEB J. 2010;24(7):2222–2234. 10.1096/fj.09-148700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann JK, Perschmann N, Spatz JP, et al. : Tunable substrates unveil chemical complementation of a genetic cell migration defect. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2(8):1162–1169. 10.1002/adhm.201200426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh MH, Carruthers VB: Toxoplasma MIC2 is a major determinant of invasion and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(8):e84. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacot D, Tosetti N, Pires I, et al. : An Apicomplexan Actin-Binding Protein Serves as a Connector and Lipid Sensor to Coordinate Motility and Invasion. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(6):731–743. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett TJ, Sibley LD: Aldolase forms a bridge between cell surface adhesins and the actin cytoskeleton in apicomplexan parasites. Mol Cell. 2003;11(4):885–894. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00113-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer J, Frischknecht F, Mair GR: Proteomic Analysis of the Plasmodium berghei Gametocyte Egressome and Vesicular bioID of Osmiophilic Body Proteins Identifies Merozoite TRAP-like Protein (MTRAP) as an Essential Factor for Parasite Transmission. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15(9):2852–2862. 10.1074/mcp.M116.058263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarque MH, Roques M, Kong-Hap M, et al. : Plasticity and redundancy among AMA-RON pairs ensure host cell entry of Toxoplasma parasites. Nat Commun. 2014;5: 4098. 10.1038/ncomms5098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JM, Rould MA, Konradt C, et al. : Disruption of TgPHIL1 alters specific parameters of Toxoplasma gondii motility measured in a quantitative, three-dimensional live motility assay. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85763. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M: Mic2KO Raw Data. Open Science Framework. 2017. Data Source [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M, Ferguson DJ, Frischknecht F: Invasion factors of apicomplexan parasites: essential or redundant? Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16(4):438–444. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morahan BJ, Wang L, Coppel RL: No TRAP, no invasion. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25(2):77–84. 10.1016/j.pt.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira CK, Templeton TJ, Lavazec C, et al. : The Plasmodium TRAP/MIC2 family member, TRAP-Like Protein (TLP), is involved in tissue traversal by sporozoites. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10(7):1505–1516. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01143.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münter S, Sabass B, Selhuber-Unkel C, et al. : Plasmodium sporozoite motility is modulated by the turnover of discrete adhesion sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6(6):551–562. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periz J, Whitelaw J, Harding C, et al. : Toxoplasma gondii establishes an extensive filamentous network consisting of stable F-actin during replication. bioRxiv. 2016. 10.1101/066522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rugarabamu G, Marq JB, Guérin A, et al. : Distinct contribution of Toxoplasma gondii rhomboid proteases 4 and 5 to micronemal protein protease 1 activity during invasion. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97(2):244–262. 10.1111/mmi.13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Buguliskis JS, Lee TD, et al. : Functional analysis of rhomboid proteases during Toxoplasma invasion. MBio. 2014a;5(5):e01795–01714. 10.1128/mBio.01795-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Sibley LD: Toxoplasma aldolase is required for metabolism but dispensable for host-cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014b;111(9):3567–3572. 10.1073/pnas.1315156111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidik SM, Huet D, Ganesan SM, et al. : A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Toxoplasma Identifies Essential Apicomplexan Genes. Cell. 2016;166(6):1423–1435.e1412. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan AA, Thathy V, Frevert U, et al. : TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90(3):511–522. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80511-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieux I, Baum J: Reassessing the mechanics of parasite motility and host-cell invasion. J Cell Biol. 2016;214(5):507–515. 10.1083/jcb.201605100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw JA, Latorre-Barragan F, Gras S, et al. : Surface attachment, promoted by the actomyosin system of Toxoplasma gondii is important for efficient gliding motility and invasion. BMC Biol. 2017;15(1):1. 10.1186/s12915-016-0343-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]