Abstract

Gender-based bias and conflation of gender and status are root causes of disparities in women’s health care and the slow advancement of women to leadership in academic medicine. More than a quarter of women physicians train in internal medicine (IM) and its subspecialties, and women physicians almost exclusively constitute the women’s health focus within IM. Thus, IM has considerable opportunity to develop women leaders in academic medicine and promote women’s health equity.

To probe whether holding an endowed chair—which confers status—in women’s health may be an effective way to advance both women leaders in academic medicine and women’s health, the authors explored the current status of endowed chairs in women’s health in IM. They found that the number of these endowed chairs in North America increased from 7 in 2013 to 19 in 2015, and all were held by women. The perceptions of incumbents and other women’s health leaders supported the premise that an endowed chair in women’s health would increase women’s leadership, the institutional stature of women’s health, and activities in women’s health research, education, and clinical care.

Going forward, it will be important to explore why not all recipients perceived that the endowed chair enhanced their own academic leadership, whether providing women’s health leaders with fundraising expertise fosters future success in increasing the number of women’s health endowed chairs, and how the conflation of gender and status play out (e.g., salary differences between endowed chairs) as the number of endowed chairs in women’s health increases.

In this Perspective, we contend and seek to demonstrate that increasing the number of endowed chairs in women’s health can be an effective way to both advance women in academic leadership and also have a positive effect on women’s health through increased research, education, and clinical initiatives.

The Unbroken Glass Ceiling

Gender disparities persist in health care, and women remain underrepresented in clinical research.1–5 For example, compared with men, women have been less likely to receive recommended treatments of cardiovascular disease and risk factors, 6–9 spirometry for establishing the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,10 or joint replacements for comparable osteoarthritis.11,12 Despite mandates from the Institute of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to include both men and women in clinical research on health conditions that have an impact on both sexes, and to analyze data by sex, 13–15 women remain underrepresented in clinical research on common conditions such as cardiovascular disease.6,7,16

Advancements in women’s health are integrally related to the advancement of women into leadership in academic medicine. 17–19 In 1995, the Commission on Graduate Medical Education in its fifth report on women and medicine20 stated that issues of equity in the status of women physicians and improvements in the quality of health care for women were so tightly bound that they could not be evaluated separately. The inextricable link between the advancement of women’s health and the advancement of women in academic medicine is fundamental to the mission of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, which seeks not only to advance research related to women’s health and increase numbers of women participants in clinical research, but also to support the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in biomedical research careers.21 Similarly, the Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health, through its National Center of Excellence initiative from 1996–2007, encouraged participating institutions to address and redress the multiple complex issues that are impeding the advancement of women’s health in education, research, and clinical practice and are preventing the realization of women physicians’ full potential for leadership.22,23

Despite representing almost half of all medical school matriculates for over 20 years, only 13% of all female full-time faculty are full professors compared with 30% for male full-time faculty.24 Furthermore, women’s representation as medical school deans and department chairs has seen little growth in the last decade,24 even in fields where the overwhelming majority of physicians have been women for quite some time.25,26 Deeply embedded gender-based biases and assumptions may underpin both the continued disparities in women’s health and the slow pace of progress of women into leadership in academic medicine.18,23,27–33 Internal medicine and its subspecialties are well positioned to address both issues because these disciplines provide the vast majority of medical care to adult women, are leading the academic growth of sex and gender based medicine,34 and in 2014 encompassed 27% of all women physicians.24 Furthermore, within internal medicine, academic and clinical programs devoted to women’s health are led almost exclusively by women.23,30,35

Endowed Chairs: A Way to Break Through the Glass Ceiling

Academic health centers can receive gifts or can allocate funds for an endowment from which the annual income is used to support a specific individual or a theme of research or clinical care. These are typically referred to as endowed chairs or endowed professorships, depending on the amount of the initial endowment, with the former representing a larger amount. When the name of the individual who provides the endowment is attached to the title, these may be referred to as named professorships. For convenience, we will refer to all of these situations as endowed chairs.

Holding an endowed chair confers status. In nearly all cultures, the roles, behaviors, or characteristics associated with women are of lower status than those associated with men.33,36–40 Recognition by a high-status group can increase social capital and confer legitimate power.41–43 Women may be particularly benefited from the external conferral of status. Amanatullah and Tinsley43 demonstrated this experimentally in two studies that found a high-status title benefited women but not men in a negotiation task. Moreover, this body of research would predict that the status of an individual female faculty member and her ability to effectively negotiate would increase when she receives an endowed chair. If the endowed chair is specifically in women’s health, academic initiatives in women’s health should benefit both from this external conferral of status and also from the increased effectiveness of the endowed chair to negotiate on behalf of women’s health programs.

Testing the Premise

To test the premise stated above, we undertook a series of efforts to assess the current status of endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine and whether holding an endowed chair appeared to support the dual goals of increasing the presence of women in academic leadership and advancing women’s health. We chose internal medicine as the focus of our efforts because more than a quarter of women physicians train in internal medicine and its subspecialties, and women physicians almost exclusively comprise the women’s health focus within internal medicine. Thus, internal medicine has considerable opportunity to develop women leaders in academic medicine and to advance the field of women’s health in medicine.

Specifically, we

identified and convened the extant internal medicine endowed chairs in women’s health in North America (in 2013),

convened an expanded community of women’s health leaders (in 2014),

queried incumbent endowed chairs and other women’s health leaders to ascertain their perspectives on endowed chairs in women’s health (in 2014), and

queried incumbent endowed chairs regarding the structure and perceived impact of their women’s health endowed chairs (in 2015).

We describe these efforts below.

Convening of internal medicine endowed chairs in women’s health in North America (2013)

In May 2013 in Boston, one of us (P.J.) sought to identify and convene, for the first time, all endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine or its subspecialties that existed in the United States or Canada. The purpose was to raise awareness of the existence of such endowed chairs and generate discussion to determine whether a case could be made for organized efforts to promote the development of more endowed chairs in women’s health within internal medicine. Endowed chairs were identified using online searches with phone calls to validate that the endowed chair was in women’s health and resided within internal medicine in a school of medicine, at the university level, or in a teaching hospital. There were 7 endowed chairs, of which 5 had incumbents, all women. These 5 endowed chairs met for a 1-day conference at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a major teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Each endowed chair presented a brief overview of her research with an emphasis on how it was improving the health of women, and indicated important questions for future research. There were opportunities for junior faculty and trainees interested in women’s health and sex and gender based medicine to meet with these leaders. The organizer led the invitees in discussions regarding their endowed chairs and whether and how holding the chair had influenced the invitees’ ability to advance the field of women’s health, the study of sex and gender differences in health and disease, and women’s academic careers. The content of these discussions made clear the benefits of organizing efforts to increase the number of endowed chairs in women’s health.

Convening an expanded community of women’s health leaders (2014)

Capitalizing on the momentum from the 2013 meeting, we (the authors) became a working group (led by C.N.B.M.) to further explore the benefits of endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine and its subspecialties. In October 2014 we convened the growing number of such endowed chairs and included other leaders whose work was at the nexus of women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine. We repeated efforts from 2013 to capture all of North America’s current endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine and its subspecialties and identified other invitees through personal queries and electronic searches. All were women. We invited 38 individuals (13 endowed women’s health chairs and 25 other leaders) to attend the meeting, titled “Women’s Health Leadership Summit: An Initiative to Increase Women’s Health Endowed Chairs in Internal Medicine and its Subspecialties,” and sent them a premeeting questionnaire capturing themes that had emerged from the first convening.

Sixteen attendees (7 endowed chairs) met for a 1.5 day conference at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Each received a packet that included several topic-relevant articles18,44–47 and an informational book on women’s philanthropy.48 Presentations and small-group discussions focused on topics concerning endowed chairs in women’s health, including

current status of women’s endowed chairs and results of the premeeting questionnaire about such chairs,

how gender stereotypes impede women’s advancement in academic medicine,

successful case studies of women’s health chairs endowed by grateful patients, philanthropists, industry, and targeted institutional initiatives,

strategies for successful philanthropy, and

individual and collective plans for action following the meeting.

The participants uniformly expressed a desire to meet again the following year and the need for more information about the current endowed chair positions.

Query of endowed chairs and other women’s health leaders (2014)

The premeeting survey based on the themes from the initial convening in 2013 was sent to the 38 invitees to the meeting just described. It asked them whether they agreed, disagreed, or were unsure whether women’s health is an opportunity for advancing women in academic leadership. They were also asked to rank-order the benefits of an endowed chair in women’s health on the following 5 areas:

helping advance women into leadership positions,

including women’s health issues in clinical care, education, and research,

raising the stature of women’s health as a discipline within internal medicine,

increasing recognition that women’s health is broader than reproductive health, and

encouraging women philanthropists.

Because a number of incumbents shared that they had needed to raise their own endowment, we included questions about experience with and perceived barriers to fundraising, the level of experience they had with grateful-patient fundraising, and their attitudes on academic–industry collaborations. Respondents rank-ordered the following barriers to fundraising for endowed chairs in women’s health within internal medicine, from most important to least:

marginalization of women’s health endowed chairs,

concern with framing women’s health in fundraising efforts,

institutional policies that determine themes for fundraising initiatives,

difficulty convincing local leaders to include women’s health endowed chairs in fundraising efforts, and

resistance to endowments for women’s health in internal medicine from departments of obstetrics–gynecology, the field historically associated with care of women, especially their reproductive health.

Of the 25 (66%) who responded to the premeeting survey, 23 (92%) agreed that women’s health provides an opportunity for advancing women in academic leadership. When asked to rank the benefits of an endowed chair in women’s health, the benefit ranked as number 1 in the list of 5 by the greatest number of respondents (8; 32%) was “increase the stature of women’s health as a discipline within internal medicine”; 16 respondents (64%) ranked this benefit within the top 2 in that list. The ability of endowed chairs in women’s health to include women’s health issues in clinical care, education, and research was ranked number 1 by 7 respondents (28%); 16 (64%) ranked this benefit within the top 2 benefits.

As mechanisms to fundraise for an endowed chair in women’s health, 13 respondents (52%) reported negligible experience with grateful-patient fundraising experience. In ranking barriers to fundraising for endowed chairs in women’s health, prohibitive institutional policies were perceived as the greatest barrier by 8 respondents (32%) and to be within the top 2 barriers by 13 respondents (52%). Pushback from the more traditional women’s health field of obstetrics–gynecology and marginalization of women’s health endowed chairs were also ranked within the top 2 barriers by 10 respondents (40%) and 9 respondents (36%), respectively.

Query of incumbent endowed chairs (2015)

The consensus of the attendees at the 2014 conference was that we needed more descriptive information on the current endowed chairs. With input from participants at the 2014 meeting, we developed a questionnaire to ascertain (1) the structure and types of endowed chairs, (2) the perceived impact of the current endowed chairs on women’s health education, research, and clinical care, and (3) the perceived ability of the position to advance women’s academic leadership (oneself and others). The methods were approved by the Cedar-Sinai Institutional Review Board with waiver of signed informed consent.

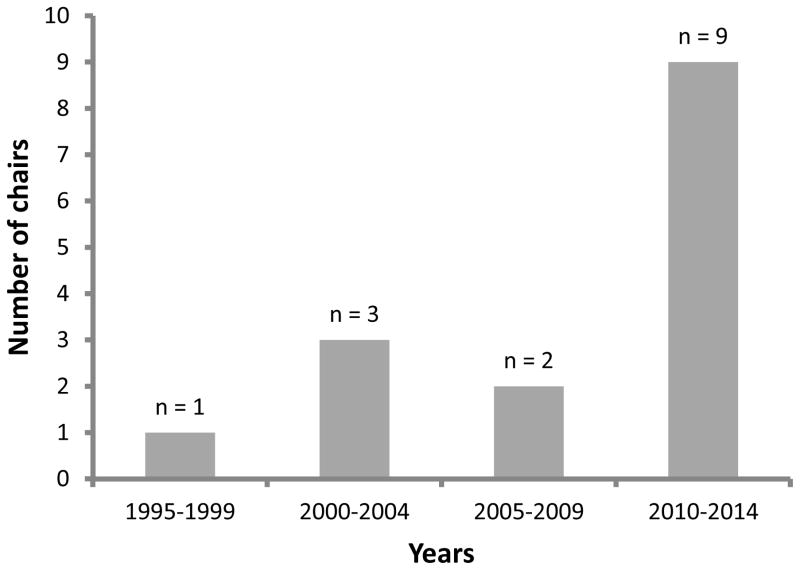

In 2015, we e-mailed an invitation to take the survey to the 18 previously identified internal medicine endowed chairs in women’s health plus one newly identified such chair, followed by two reminders. Voluntarily clicking the link to the online survey indicated informed consent. Fifteen of the 19 endowed women’s health chairs (74%) responded to the survey. The greatest number of endowed chairs among respondents (9; 60%) were established during the period 2010–2014 (see Figure 1). Tables 1 and 2 provide information about the endowed chairs. Each was the first recipient to hold the position, and a third of the respondents (5; 33%) had developed their own endowed chairs. The dollar amount of the endowment for the 9 respondents who reported that information ranged from $1.2 million to $3.0 million, and the rules for spending and access to funds varied considerably from receiving salary support only (for 4 respondents) to having access to a wide range in the amount of discretionary funds. Eight of the 9 respondents said that the source for the endowment was most often a donor.

Figure 1.

Numbers of endowed chairs in women’s health in North American departments of internal medicine in recent years. In 2015, the authors, through online searches, identified 19 endowed chairs in women’s health in departments of medicine. Fifteen responded to a survey and indicated the year in which their endowed chair in women’s health was established. In all cases, the respondent was the first occupant to hold the position.

Table 1.

Description of Endowed Chairs in Women’s Health Provided by Incumbents (N=15)

| Descriptor | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Formal letter of appointment | 14 (93) |

| Requires reappointment | 5 (33) |

| Incumbent developed the chair | 5 (33) |

| Provides salary | 6 (40) |

| Provides discretionary or research funds | 9 (60) |

| Does not require fulfillment of institutional duties | 8 (53) |

| Development office with expertise or interest in raising funds for women’s health | 6 (40) |

| Descriptor (number of respondents) | Responses |

| Current dollar amount of endowment (9) |

|

| Amount Chair can spend (15) |

|

| Funding source for endowment (13) |

|

Table 2.

Financial Characteristics of Endowed Chairs in Women's Health in Departments of Internal Medicine, North America, 2015a

| Characteristic | No. (%) respondentsb |

|---|---|

| Current dollar amount of endowment | 9 |

|

9 (100) |

| Amount chair can spend | 15 |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

3 (20) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

4 (26) |

| Funding source for endowment | 13 |

|

8 (61) |

|

2 (15) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

|

1 (7) |

The authors e-mailed a survey to the 19 North American incumbent endowed chairs in women's health in departments of internal medicine, whom they were able to identify through online searches. Fifteen respondents (74%) supplied the information in this table.

Percentages of respondents for the items within each of the three characteristics are based on the number of respondents to each characteristic overall; the numbers were not the same. For example, there were 13 respondents overall for questions in the category “Funding source for endowment” but 15 respondents overall for questions in “Amount chair can spend.”

Table 3 shows the numbers and percentages of the 15 out of 19 women’s health endowed chairs who responded affirmatively in 2015 to questions about the impact of their position, along with examples they provided. Being able to advance sex and gender based research was endorsed by 14 of the 15 respondents (93%), and the remaining respondent indicated that she was new to her position but anticipated that it would advance such research. Over half of the respondents indicated that the endowed chair had enabled them to increase sex and gender based content in the education of medical students (8; 73%), the education of residents (9; 82%), and the education of faculty (9; 82%). Many, but not all, of the respondents indicated that holding the chair had promoted their own leadership (7; 47%), facilitated new grant funding (10; 67%) and allowed recruitment of new faculty (many of whom were women) who would further advance women’s health (6; 40%).

Table 3.

Perceived Impact of Endowed Chair in Women’s Health by 15 of 19 Incumbents in 2014

| Perceived Impact by Incumbent | Number Responding Yes (%) | Examples (excerpted quotes from written responses) |

|---|---|---|

| Promoted your institutional executive leadership | 7 (47) |

|

| Allowed you to advance sex and gender based research | 14 (93) |

|

| Facilitated new grant funding | 10 (67) |

|

| Increased sex and gender based medicine in medical school curriculum | 8 (73) |

|

| Increased sex and gender based medicine in resident training | 9 (82) |

|

| Increased sex and gender based medicine into faculty CME | 9 (82) |

|

| Enhanced clinical care of women | 11 (73) |

|

| Allowed you to recruit new faculty with the goal of advancing women’s health | 6 (40) |

|

| Improved ability to raise funds to advance the field of women’s health | 6 (40) |

|

Questions Answered, Questions Remaining

Across these 4 initiatives to assess the current status of endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine, we found the number of chairs is growing and the consensus is that organized efforts for further increasing the number are warranted. Although their accomplishments may have been the reason for their receiving an endowed chair rather than its result, the impact of the current cohort of endowed chairs in women’s health has been far-reaching, encompassing professional career development, novel curricular offerings, new women’s health and sex and gender based research, and improved access to clinical care for women. Multiple different strategies appeared to have been successful in establishing endowed chairs in women’s health; however, most of the current endowed chairs and women leaders in women’s health had no fundraising experience. Increasing competencies in fundraising among women’s health leaders in academic internal medicine may be an important area for education and skill-building—especially since one third (5 of 15) of the women’s health endowed chairs who responded to our survey had established their own positions. Institutional restrictions on fundraising priorities were seen as a major barrier to establishing endowed chairs in women’s health, indicating that discussions with those who set fundraising priorities are important in making the case for the institutional benefits of endowed chairs in women’s health. The examples we presented of the impact of the current women’s health endowed chairs may be useful as persuasive evidence of what can be accomplished by developing an endowed chair in women’s health in internal medicine.

Title IX did much to eliminate explicit institutional structures, such as quotas, that historically prevented women’s entry into high-status occupations and positions.49 However, gender is such a diffuse and automatically triggered status cue that the assumption of low status can and does tacitly influence judgment and decision making in ways that disadvantage women physicians in hiring,50 salary,51–54 grant funding,27,55–58 and leadership opportunities.28,59,60 Even the percentages of women physicians in medical specialties and subspecialties correlate with the prestige and remuneration of the specialty: the alignment of gender and status resulting in higher percentages of female physicians entering relatively low-status, lower paying specialties and higher percentages of male physicians entering high-status, higher paying specialties.29,61,62

Receiving an endowed chair in women’s health should be an effective way to increase social capital, confer legitimate power, and foster effective negotiation outcomes—to the benefit of both the recipient and women’s health.41–43 Therefore, we found it interesting that more than half of the current endowed chairs (8 out of 15) did not perceive that holding the position had promoted their own leadership. Some offered that they were already in a leadership position when they received the endowed chair. We do not have explanations for the negative response from others, but this provides an area for more in-depth exploration. It is possible that rather than receiving the status benefit of an endowed chair, the opposite is occurring. That is, the low status imbued to anything associated with the female gender may be lowering the status of an endowed chair that is designated for women’s health and held by a woman. One of us (M.C.) cited similar concerns regarding the enthusiasm by some to seek accreditation for women’s health fellowships.30

Even though our investigation was descriptive and had a small sample size, we captured almost the entire population of endowed chairs in women’s health in departments of internal medicine in North America. From our sequence of efforts, we believe that our initial premise is conceptually sound and borne out by the experiences of current women’s health endowed chairs. Increasing the number of endowed chairs in women’s health in internal medicine can be an effective way to both advance women in academic leadership and also have a positive effect on women’s health through increased research, education, and clinical initiatives. Going forward, it will be important to explore why not all recipients perceived that the endowed chair enhanced their own academic leadership, whether providing women’s health leaders with fundraising expertise fosters future success in increasing the number of women’s health endowed chairs, and how the conflation of gender and status play out as the number of endowed chairs in women’s health increases (e.g., will endowed chairs in women’s health have lower salaries than endowed chairs in other areas of internal medicine?).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the endowed women’s health chairs and other leaders in academic women’s health and leadership for their participation in this work and for all they have done to improve the lives of women.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by (1) the Edythe L. Broad Women’s Heart Research Fellowship, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; the Barbra Streisand Women’s Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Los Angeles, California; the Linda Joy Pollin Women’s Heart Health Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; the Constance Austin Fellowship Endowment, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; and the Erika Glazer Women’s Heart Health Project, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; and (2) the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Visiting Professorship in Women’s Health, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and the Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: Not applicable. The 2015 questionnaire was approved by the Cedar-Sinai Institutional Review Board with waiver of signed informed consent.

Contributor Information

Molly Carnes, Director, Center for Women’s Health Research; professor, Departments of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin; and director, Women’s Health, William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

Paula Johnson, At the time this article was written, was executive director, Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology and Division of Women’s Health, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and professor of epidemiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. She is now president, Wellesley College, Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Wendy Klein, Senior deputy director emerita, Institute for Women’s Health, and associate professor emerita, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia.

Marjorie Jenkins, Director and chief science officer, Laura W. Bush Institute for Women’s Health, and professor of medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Amarillo, Texas.

C. Noel Bairey Merz, Director, Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center, and professor of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute, Los Angeles, California.

References

- 1.Carnes M. Health care in the US: Is there evidence for systematic gender bias? WMJ. 1999;98:15, 17–19, 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kent JA, Patel V, Varela NA. Gender disparities in health care. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79:555–559. doi: 10.1002/msj.21336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller SE, Koch A, Pellettieri B, Carnes M. Inclusion, analysis, and reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials: Have we made progress? J Women’s Health. 2011;20:315–320. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller SE, Adams MG, Carnes M. Adherence to federal guidelines for reporting of sex and race/ethnicity in clinical trials. J Women’s Health. 2006;15:1123–1131. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhruva SS, Bero LA, Redberg RF. Gender bias in studies for Food and Drug Administration premarket approval of cardiovascular devices. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:165–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bairey Merz CN, Regitz-Zagrosek V. The case for sex- and gender-specific medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1348–1349. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McSweeney JC, Rosenfeld AG, Abel WM, et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Preventing and experiencing ischemic heart disease as a woman: State of the science. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:1302–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvie JL, Foody JM. Recognizing and improving health care disparities in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2010;12:488–496. doi: 10.1007/s11886-010-0135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AM, Mumma B, Sease KL, Robey JL, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Gender bias in cardiovascular testing persists after adjustment for presenting characteristics and cardiac risk. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:599–605. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.03.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delgado A, Saletti-Cuesta, Lopez-Fernandez LA, Gil-Garrido N, Luna del Castillo JD. Gender inequalities in COPD decision-making in primary care. Respir Med. 2016;114:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, et al. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1016–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Wright JG. Patient gender affects the referral and recommendation for total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1829–1837. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institutes of Health. Better Oversight Needed to Help Ensure Continued Progress Including Women in Health Research. United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountbility Office; 2015. GAO-16-13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wizemann TM, Pardue ML, editors. Committee on Understanding the Biology of Sex and Gender Differences, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler NE, Adashi EY, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Committee on Women’s Health Research; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine. Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melloni C, Berger JS, Wang TY, et al. Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:135–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.868307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisman CS. Women’s Health Care: Activist Traditions and Institutional Change. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller S. Women’s health and women in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health. 2008;17:1453–1462. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haseltine FP, Jacobson BG, editors. Women’s Health Research: A Medical and Policy Primer. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Council on Graduate Medical Education. Fifth Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Health Resources and Services Administration; 1995. Women and Medicine: Physician Education in Women’s Health and Women in the Physician Workforce. [Google Scholar]

- 21.NIH Office for Research on Women’s Health. Women in Biomedical Careers: Dynamics of Change, Strategies for the 21st Century. Bethesda, MD: 1992. NIH No. 95-3565. [Google Scholar]

- 22.United States Public Health Service Office on Women’s Health. Action Plan for Women’s Health. Washington, DC: 1991. DHHS No. 91-50214. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carnes M, VandenBosche G, Agatisa PK, et al. Using women’s health research to develop women leaders in academic health sciences: The National Centers of Excellence in Women’s Health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:39–47. doi: 10.1089/152460901750067106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed July 20, 2016];The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership, 2013–2014. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/

- 25.Hofler LG, Hacker MR, Dodge LE, Schutzberg R, Ricciotti HA. Comparison of women in department leadership in obstetrics and gynecology with those in other specialties. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:442–447. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stapleton FB, Jones D, Fiser DH. Leadership trends in academic pediatric departments. Pediatrics. 2005;116:342–344. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carnes M, Bland C. Viewpoint: A challenge to academic health centers and the National Institutes of Health to prevent unintended gender bias in the selection of clinical and translational science award leaders. Acad Med. 2007;82:202–206. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d939f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinze SW. Gender and the body of medicine or at least some body parts: (Re)constructing the prestige hierarchy of medical specialties. Sociol Q. 1999;40:217–239. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carnes M, Vogelman B. Women’s health fellowships: Examining the potential benefits and harms of accreditation. J Womens Health. 2015;24:341–348. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1504–1510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henrich JB. Women’s health education initiatives: Why have they stalled? Acad Med. 2004;79(4):283–288. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, Kolehmainen C. Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2015;126:197–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkins M, Chin EL, editors. Sex and Gender Medical Education Summit: A Roadmap for Curricular Innovation. Conference Proceedings; Oct 18–19, 2015; [Accessed July 20, 2016]. http://sgbmeducationsummit.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tilstra SA, Kraemer KL, Rubio DM, McNeil MA. Evaluation of VA Women’s Health Fellowships: Developing leaders in academic women’s health. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:901–907. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2306-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridgeway CL. Gender, status, and leadership. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glick P, Wilk K, Perreault M. Images of occupations: Components of gender and status in occupational stereotypes. Sex Roles. 1995;32:565–582. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alksnis C, Desmarais S, Curtis J. Workforce segretation and the gender wage gap: Is “women’s” work valued as highly as “men’s”? J Appl Soc Psychol. 2008;38:1416–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goff BA, Muntz HG, Cain JM. Is Adam worth more than Eve? The financial impact of gender bias in the federal reimbursement of gynecological procedures. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:372–377. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goff BA, Muntz HG, Cain JM. Comparison of 1997 Medicare relative value units for gender-specific procedures: Is Adam still worth more than Eve? Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:313–319. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raven BH. The bases of power and the power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2008;8:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Portes A. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amanatullah ET, Tinsley CH. Ask and ye shall receive? How gender and status moderate negotiation success. Negot Confl Manag R. 2013;6:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaatz A, Carnes M. Stuck in the out-group: Jennifer can’t grow up, Jane’s invisible, and Janet’s over the hill. J Womens Health. 2014;23:481–484. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nattinger AB. Promoting the career development of women in academic medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:323–324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jagsi R, Butterton JR, Starr R, Tarbell NJ. A targeted intervention for the career development of women in academic medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:343–345. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bickel J, Wara D, Atkinson BF, et al. Increasing women’s leadership in academic medicine: Report of the AAMC Project Implementation Committee. Acad Med. 2002;77:1043–1061. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw-Hardy S, Taylor MA. Women & Philanthropy: Boldly Shaping a Better World. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C., Chapter 38, Section 1681 – 1688. Title 20 Education. 1972.

- 50.Isaac C, Lee B, Carnes M. Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84:1440–1446. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ba00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lo Sasso AT, Richards MR, Chou CF, Gerber SE. The $16,819 pay gap for newly trained physicians: The unexplained trend of men earning more than women. Health Aff. 2011;30:193–201. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in salary in a recent cohort of early-career physician-researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88:1689–1699. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a71519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Stewart A, Sambuco D, DeCastro R, Ubel PA. Gender differences in the salaries of physician researchers. JAMA. 2012;307:2410–2417. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:486–490. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carnes M, Geller S, Fine E, Sheridan J, Handelsman J. NIH Director’s Pioneer Awards: Could the selection process be biased against women? J Womens Health. 2005;14:684–691. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. Sociology. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science. 2008;322:1472–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1165878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pohlhaus JR, Jiang H, Wagner RM, Schaffer WT, Pinn VW. Sex differences in application, success, and funding rates for NIH extramural programs. Acad Med. 2011;86:759–767. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821836ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaatz A, Magua W, Zimmerman DR, Carnes M. A quantitative linguistic analysis of National Institutes of Health R01 application critiques from investigators at one institution. Acad Med. 2015;90:69–75. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: Patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one U.S. College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78:500–508. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koenig AM, Eagly AH, Mitchell AA, Ristikari T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol Bull. 2011;137:616–642. doi: 10.1037/a0023557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isaac C, Chertoff J, Lee B, Carnes M. Do students’ and authors’ genders affect evaluations? A linguistic analysis of Medical Student Performance Evaluations. Acad Med. 2011;86:59–66. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318200561d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carnes M, Bartels CM, Kaatz A, Kolehmainen C. Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:197–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]