Abstract

Objective

There have been hypotheses that early life adiposity gain may influence blood pressure (BP) later in life. We examined associations between timing of height, body mass index (BMI) and adiposity gains in early life with BP at 48 months in an Asian pregnancy-birth cohort.

Methods

In 719 children, velocities for height, BMI and abdominal circumference (AC) were calculated at five intervals [0-3, 3-12, 12-24, 24-36 and 36-48 months]. Triceps (TS) and subscapular skinfold (SS) velocities were calculated between 0-18, 18-36 and 36-48 months. Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was measured at 48 months. Growth velocities at later periods were adjusted for growth velocities in preceding intervals as well as measurements at birth.

Results

After adjusting for confounders and child height at BP measurement, each unit z-score gain in BMI, AC, TS and SS velocities at 36-48 months were associated with 2.3 (95% CI:1.6, 3.1), 2.1 (1.3, 2.8), 1.4 (0.6, 2.2) and 1.8 (1.0, 2.6) mmHg higher SBP respectively, and 0.9 (0.4, 1.4), 0.9 (0.4, 1.3), 0.6 (0.1, 1.1) and 0.8 (0.3, 1.3) mmHg higher DBP respectively. BMI and adiposity velocities (AC, TS or SS) at various intervals in the first 36 months however, were not associated with BP. Faster BMI, AC, TS and SS velocities, but not height, at 36-48 months were associated with 0.22 (0.15, 0.29), 0.17 (0.10, 0.24), 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) and 0.15 (0.08, 0.23) units higher SBP z-score respectively, and OR=1.46 (95% CI: 1.13-1.90), 1.49 (1.17-1.92), 1.45 (1.09-1.92) and 1.43 (1.09, 1.88) times higher risk of prehypertension/hypertension respectively at 48 months.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that faster BMI and adiposity (AC, TS or SS) velocities only at the preceding interval before 48 months (36-48 months), but not at earlier intervals in the first 36 months, are predictive of BP and prehypertension/hypertension at 48 months.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have been identified as the leading global cause of death, with 63% of deaths attributable to NCDs such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes (1). As projected NCD rates continue to rise worldwide, their burden is rising across all income groups (2). Raised blood pressure (BP) has been estimated to cause about 12.8% of all NCD-related deaths (1). More recently, the prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension has also increased markedly among children and adolescents (3). Given that high BP in childhood is a risk factor for later CVD (4, 5), insights into its early life risk factors are important for developing preventive strategies to reduce the premature mortality associated with hypertension and CVD.

Many observational studies have linked rapid postnatal weight gain with increased risk of later CVD and metabolic syndrome, in line with the “growth acceleration hypothesis” proposed by Singhal et al (6). The hypothesis postulated that faster weight gain during early infancy may adversely program components of metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, suggesting that rapid postnatal weight gain may increase BP later in life. During critical periods of the early life course, accelerated weight gain may increase later BP and CVD risk. Rapid increases in weight and height in the first few months of life have been associated with higher systolic BP in early childhood (7–10), adolescence (11) and adulthood (12, 13). Recent cohort studies in Belarus, the United Kingdom and the United States however, have shown associations between faster weight gain during early childhood (between 1-5 years) and higher BP (9, 10, 14), with stronger effect sizes observed closer to the age of BP measurement.

The current literature linking timing of postnatal weight or adiposity gain with childhood BP is based primarily on Western populations (7–11, 13, 14). To our knowledge, only one study (12) has examined the timing of postnatal weight gain in relation to later BP in Asian populations, despite their higher risk of metabolic disease (15). We therefore examined the associations between gains in height, BMI and adiposity in infancy and early childhood and later BP in an Asian birth cohort, the Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) study.

Methods

Study population

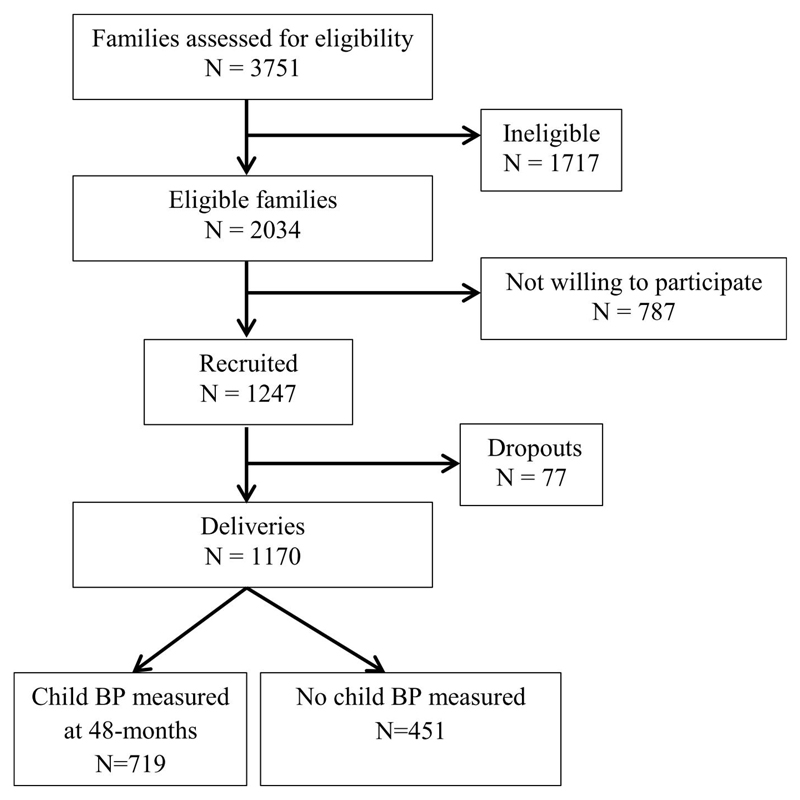

The GUSTO study has been previously described in detail (16, 17). Briefly, pregnant women in their first trimester were recruited from two major public hospitals in Singapore with obstetric services (KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and the National University Hospital) between June 2009 and September 2010. Eligible women were Singapore citizens or permanent residents who were of Chinese, Malay, or Indian ethnicity with homogeneous parental ethnic backgrounds (mother and father of infant). Women receiving chemotherapy, taking psychotropic drugs, or with diabetes mellitus were excluded. Of 3751 screened women, 2034 mothers met these criteria, of whom 1247 (response rate: 61.3%) were recruited and 1170 had singleton deliveries (Figure 1). The women gave informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by both the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board and the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

GUSTO recruitment chart and eventual study sample

Antenatal data

Socio-demographic data (age, ethnicity (self-reported), education level and parity) were obtained at recruitment, Gestational age (GA) was assessed at the first ultrasound dating scan during recruitment. Scans were conducted in a standard manner at both hospitals by trained ultrasonographers, with GA reported in completed weeks. At 26–28 weeks of gestation, maternal weight and height were measured with the use of SECA 803 Weighing Scale (SECA Corp, Hamburg, Germany) and SECA 213 Stadiometer (SECA Corp.), respectively. Maternal body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by the square of height.

Infant anthropometry measurements

All anthropometric measurements were obtained using standardized protocols (18). Measurements of child weight, length/height and abdominal circumference (AC) were obtained at birth and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months of age. Weight was measured to the nearest gram using calibrated scales [SECA 334 Weighing Scale (birth to 18 months) and SECA 803 Weighing Scale (24 to 48 months)]. Recumbent length (from birth to 24 months) was measured from the top of the head to soles of feet using an infant mat (SECA 210 Mobile Measuring Mat) to the nearest 0.1 cm. Standing height (at 24 to 48 months) was measured using a stadiometer (SECA stadiometer 213) from the top of participant’s head to his or her heels. Both measures of recumbent length and standing height were obtained the 24-month visit, even for infants who were seen before or after 24 months. AC was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm, using a non-stretchable measuring tape (SECA 212 Measuring Tape, SECA Corp.). For reliability, all measurements were taken in duplicates and averaged. Body mass index (BMI) at each age was calculated by weight divided by the square of length or height.

Triceps (TS) and subscapular (SS) skinfold thicknesses were measured at birth and at 18-, 24-, 36- and 48-months in triplicates using Holtain skinfold calipers (Holtain Ltd, Crymych, UK) on the right side of the body, recorded to the nearest 0.2 mm. Anthropometric training and standardization sessions were conducted quarterly (once every 3 months), and observers were trained to obtain anthropometric measurements that, on average, were closest to the values measured by a master anthropometrist. Assessment of reliability was estimated by inter-observer technical error of measurement (TE) and coefficient of variation (CV) (Supplementary Table 1) (19). In addition, the TE and CV of the various anthropometric measures do not suggest a larger error at ages below 24 months (Supplementary Table 2). As the TE for length and height at age 24 months showed no differences between length (0.01cm) and height (0.01cm) (Supplementary Table 2), we utilized measures of recumbent length at age 24 months for the analyses reported in this paper.

Blood pressure measurements

Based on a standardized protocol (20), maternal BP at 26-28 weeks of gestation was taken by trained research coordinators. Mothers rested for at least 10 minutes prior to BP measurement, and the peripheral systolic (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) were measured thrice from the upper arm at 30 to 60 second intervals with an oscillometric device (MC3100, HealthSTATS International Pte Ltd, Singapore). An average of the three readings was calculated if the difference between readings was less than 10 mmHg; otherwise, measurements were repeated.

Child BP was measured by trained research personnel during the clinic visits. The child was required to sit with the mother for at least 5 minutes in a quiet room. Peripheral SBP and DBP were measured twice from the right upper arm using a Dinamap CARESCAPE V100 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI), with the arm resting at the chest level. An average of both BP readings was calculated if the difference between readings was less than 10 mmHg; otherwise, a third reading was taken and the average of the three readings used instead. The decision to use this method of BP measurement in children was made a priori during development of the study protocol. It was chosen over manual measurement of BP because of its ease of use in young children and its applicability when a number of research personnel take the measurements. The feasibility and validity of using the Dinamap device for blood pressure measurement in young children has been demonstrated before in other cohort studies (21, 22).

Prehypertension/hypertension was defined as SBP or DBP above the 90th percentile for the child’s sex, age and height. BP z-scores were calculated based on age-, sex-, and height-specific reference values published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (23). As there is currently no reference for blood pressure percentiles in the Singapore population, we utilized the U.S reference values published by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Height, BMI and AC velocities were analyzed as rate of change per month across five intervals [0 to 3, 3 to 12, 12 to 24, 24 to 36 and 36 to 48 months]. Skinfold thickness (TS or SS) gain velocities were analyzed as rate of change per month across 0 to 18, 18 to 36 and 36 to 48 months. Birth anthropometry and growth velocities were standardized to z-scores within the study cohort to allow direct comparison of effect estimates across different time intervals.

Multivariable linear regression was used to analyze associations between birth anthropometry and growth velocities with child BP at 48 months, adjusting for the following potential confounders: maternal age, parity, education level, height and BMI at 26-28 weeks of gestation, ethnicity, BP and child sex. The child’s exact age at the 48-month visit was also included as a covariate to improve precision. Given their tendency to track over time, growth velocities at later periods were additionally adjusted for growth velocities in preceding intervals (i.e., conditional on earlier time intervals). The adjusted estimates reflect how an individual child deviates from his or her own previous growth trajectory. The main advantage of this approach is that growth during a given interval is analyzed independently from the earlier growth trajectory (24). The correlations for each growth velocity variable at different intervals with measured height at 48 months is presented in Supplementary Table 3, with all correlations (except for height gain velocities) being less than 0.20. As height is a strong determinant of childhood BP (25, 26), all analyses (except for those involving height gain velocities) included height at age 48 months as a covariate. The analyses were also repeated using age-, sex- and height-specific BP z-scores as the outcome.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze associations between birth anthropometry and growth velocities with prehypertension/hypertension risk at 48 months, adjusting for ethnicity, maternal age, parity, education level, height, BMI and BP at 26-28 weeks gestation. Potential effect modification by birth weight-for-GA, sex and ethnicity were investigated by adding interaction terms with the growth variables to the fully-adjusted model. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of our findings, by determining age- and sex-specific z-scores for height, BMI, triceps and subscapular skinfolds using the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards (27), while z-scores for AC were calculated internally using the GUSTO cohort. We then reran the analyses with child BP, BP z-score and prehypertension/hypertension as outcomes, using the z-score velocities across the same intervals as the exposure variable. Multiple imputation was used to account for missing values of maternal height (n=15), BMI (n=23), education level (n=4), SBP and DBP (n=133 for both), with 20 imputations based on the Markov-chain Monte Carlo technique, using MI IMPUTE to impute the missing values and MI ESTIMATE to analyze the imputed datasets. All analyses were performed using Stata 13 software (StataCorp LP, TX).

Results

Complete BP measurements were available for 719 children at 48 months (Figure 1). No significant differences in baseline characteristics were seen between those with (n=719) and without (n=451) child BP measurements, with the exception of maternal age (p=0.003) and birth length (p=0.021) (Supplementary Table 4). Characteristics of subjects included in the study are summarized in Table 1. Compared to Chinese mothers, Malay mothers tend to be younger, have lower educational attainment, have higher BMI, SBP and DBP (all p<0.01). Child characteristics also differed significantly across the three ethnic groups, including GA at delivery, birth length, SBP and DBP at 48 months (all p<0.05). 12.8% of children (n=92) had prehypertension/hypertension at age 48 months. Growth velocities for all measures monotonically declined through childhood (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of study subjects

| Maternal characteristics | Chinese (n = 406) | Malay (n = 186) | Indian (n = 127) | p value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 32.1 ± 4.6 | 329.3 ± 5.5** | 30.1 ± 5.0 | <0.001 |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||

| < 12 years | 117 (29.0%) | 126 (68.5%) | 34 (26.8%) | |

| ≥ 12 years | 287 (71.0%) | 58 (31.5%)** | 93 (73.2%) | |

| Parity | 0.012 | |||

| Primiparous | 199 (49.0%) | 78 (41.9) | 44 (34.6%) | |

| Multiparous | 207 (51.0%) | 108 (58.1%) | 83 (65.4%)** | |

| Maternal anthropometry | ||||

| Height (cm) | 158.9 ± 5.6 | 157.0 ± 5.7** | 157.4 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 3.4 | 28.4 ± 5.3** | 27.7 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Maternal BP1 | ||||

| SBP1 (mmHg) | 107.3 ± 11.8 | 113.9 ± 15.5** | 111.0 ± 10.6 | <0.001 |

| DBP1 (mmHg) | 65.1 ± 9.3 | 68.9 ± 10.0** | 67.4 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Sex | 0.777 | |||

| Male | 202 (49.8%) | 88 (47.3%) | 65 (51.2%) | |

| Female | 204 (50.2%) | 98 (52.7%) | 62 (48.8%) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.4 ± 1.4 | 38.1 ± 1.3* | 38.1 ± 2.2* | 0.028 |

| Age at BP measurement (months) | 49.4 ± 1.4 | 49.3 ± 0.9 | 49.5 ± 1.1 | 0.522 |

| Birth anthropometry | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 0.053 |

| Height (cm) | 48.9 ± 2.3 | 48.2 ± 2.0** | 48.7 ± 2.5 | 0.008 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 28.3 ± 2.2 | 28.6 ± 2.5 | 28.1 ± 2.4 | 0.208 |

| Triceps skinfolds (mm) | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 0.298 |

| Subscapular skinfolds (mm) | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 0.101 |

| BP measurement | ||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 96.9 ± 8.8 | 98.3 ± 9.4** | 98.9 ± 8.6 | 0.043 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 57.6 ± 5.3 | 58.2 ± 5.7* | 59.2 ± 5.5* | 0.012 |

BP: blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure DBP: diastolic blood pressure

p value across 3 ethnic groups were determined with the use of a chi-square analysis (categorical) or 1-factor ANOVA (continuous)

*p<0.05 or **p<0.01 compared with Chinese [determined with the use of a chi-square analysis (categorical) or 2-sample t-test]

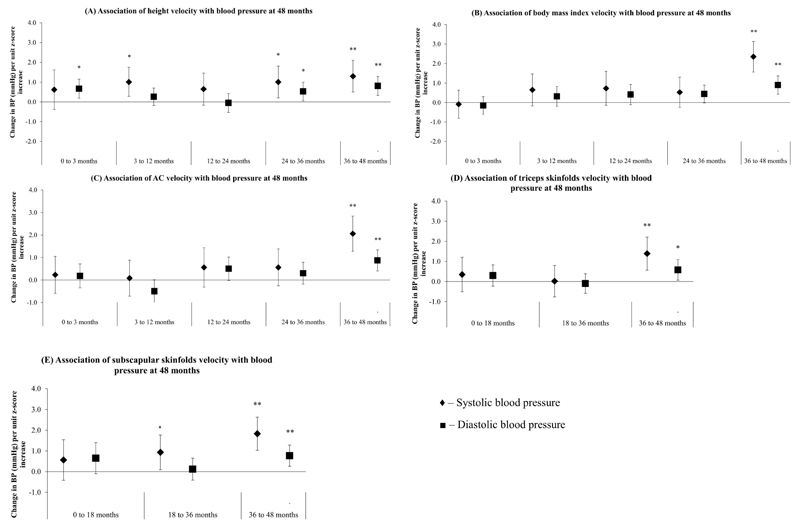

Associations of height gain velocities with child BP

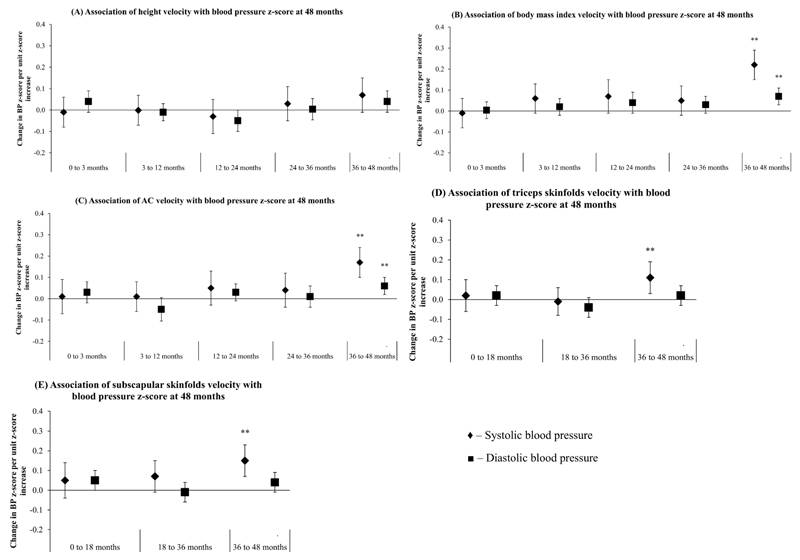

Faster gains in height at ages 3 to 12, 24 to 36 and 36 to 48 months were positively associated with SBP, with each unit z-score increase in height gain velocity associated with 1.0 (0.3, 1.7), 1.0 (0.2, 1.8) and 1.3 (0.5, 1.9) mmHg higher SBP, respectively (Figure 2A). Faster height gain velocities at ages 24 to 36 and 36 to 48 months were also positively associated with DBP: 0.5 (0.05, 1.0) and 0.8 (0.3, 1.3) mmHg (Figure 2A). Faster gains in height velocity at 0 to 3 months were associated with increased DBP only: 0.7 (0.2, 1.2) mmHg. No significant associations however, were observed between height gains across all intervals with BP z-score at age 48 months (Figure 3A).

Figure 2.

Associations between (A) height gain velocity, (B) body mass index gain velocity, (C) abdominal circumference velocity, (D) triceps skinfolds velocity and (E) subscapular skinfolds velocity with systolic (♦) and diastolic (■) blood pressure at age 48 months. All models were adjusted for maternal age, parity, education level, height, BMI, ethnicity, blood pressure, child’s age and sex. Growth velocities at later periods were additionally adjusted for growth velocities at preceding intervals as well as measurement at birth. Models with body mass index, abdominal circumference, triceps and subscapular skinfolds gain velocities were additionally adjusted for child height at age 48 months. **p<0.01; *p<0.05

Figure 3.

Associations between (A) height gain velocity, (B) body mass index gain velocity, (C) abdominal circumference velocity, (D) triceps skinfolds velocity and (E) subscapular skinfolds velocity with systolic (♦) and diastolic (■) blood pressure z-score at age 48 months. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure z-scores were derived from age-, sex- and height-specific reference values from American Academy of Pediatrics. All models were adjusted for maternal age, parity, education level, height, BMI, ethnicity and blood pressure. Growth velocities at later periods were additionally adjusted for growth velocities at preceding intervals as well as measurement at birth. **p<0.01; *p<0.05

Associations of BMI gain velocities with child BP

No significant associations were noted between birth weight-for-GA z-score and child BP at 48 months. After adjusting for potential confounders, faster BMI gain velocities at age 36 to 48 months was significantly associated with BP, with each unit z-score increase associated with 2.3 (95% CI:1.6, 3.1) mmHg higher SBP and 0.9 (0.4, 1.4) mmHg higher DBP respectively (Figure 2B). No significant associations were observed however, between BMI gains at 0 to 3, 3 to 12, 12 to 24 and 24 to 36 months with BP. Only faster BMI gain velocities at 36 to 48 months were associated with higher SBP and DBP z-score: 0.22 (0.15, 0.29) and 0.07 (0.02, 0.11) units respectively (Figure 3B).

Associations of AC gain velocities with child BP

No significant associations were noted between birth AC, and AC gain velocities at ages 0 to 3, 3 to 12, 12 to 24 and 24 to 36 months with child BP at 48 months. At age 36 to 48 months however, each unit z-score increase in AC gain velocity was associated with 2.1 (1.3, 2.8) mmHg higher SBP and 0.9 (0.4, 1.3) higher DBP respectively (Figure 2C). Faster AC gain velocities at age 36 to 48 months were also associated with higher SBP and DBP z-score: 0.17 (0.10, 0.24) and 0.06 (0.02, 0.10) units respectively (Figure 3C).

Associations of skinfold gain velocities with child BP

No significant associations were observed between birth TS and SS with BP. Faster TS gain velocities at age 36 to 48 months, but not 0 to 18 and 18 to 36 months, were significantly associated with higher SBP and DBP: 1.4 (0.6, 2.2) and 0.6 (0.1, 1.1) mmHg respectively (Figure 2D). Faster SS gain velocities at ages 18 to 36 and 36 to 48 months was associated with higher SBP [0.9 (0.1, 1.8) and 1.8 (1.0, 2.6) mmHg respectively] (Figure 2E). Faster TS and SS gain velocities at age 36 to 48 months were also associated with higher SBP z-score: 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) and 0.15 (0.08, 0.23) units respectively (Figures 3D-E).

Furthermore, no significant interactions between sex, ethnicity or birth weight-for-gestational age with gains in height, BMI, AC or skinfolds were observed during any time interval on later BP.

Associations of growth velocities with child prehypertension/hypertension

No associations were observed between birth anthropometry, height, BMI and adiposity gain at age 0 to 3 months with prehypertension/hypertension risk at 48-months (Table 2). Each unit z-score gain in height velocity at 3 to 12 months however, was associated with a higher risk of prehypertension/hypertension: OR (95% CI) = 1.45 (1.12, 1.88). Faster gains in BMI and AC velocities during 12 to 24 months were also associated with a higher risk of prehypertension/hypertension: 1.40 (1.04, 1.90) and 1.46 (1.11, 1.93) respectively. Faster gains in BMI, AC, TS and SS velocities, but not height, at age 36 to 48 months were associated with higher risk of prehypertension/hypertension at 48-months: 1.46 (1.13, 1.90), 1.49 (1.17, 1.92), 1.45 (1.09, 1.92) and 1.43 (1.09, 1.88) respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between height, BMI, abdominal circumference, triceps and subscapular skinfold velocities with prehypertension/hypertension at 48 months

| OR1 | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| low | high | ||

| Height gain velocity | |||

| 0 to 3 months | 1.20 | 0.92 | 1.55 |

| 3 to 12 months | 1.45 | 1.12 | 1.88 |

| 12 to 24 months | 1.13 | 0.85 | 1.49 |

| 24 to 36 months | 1.08 | 0.83 | 1.42 |

| 36 to 48 months | 1.16 | 0.88 | 1.52 |

| BMI gain velocity2 | |||

| 0 to 3 months | 1.02 | 0.79 | 1.32 |

| 3 to 12 months | 1.23 | 0.92 | 1.65 |

| 12 to 24 months | 1.40 | 1.04 | 1.90 |

| 24 to 36 months | 1.19 | 0.93 | 1.51 |

| 36 to 48 months | 1.46 | 1.13 | 1.90 |

| AC gain velocity2 | |||

| 0 to 3 months | 1.09 | 0.83 | 1.46 |

| 3 to 12 months | 1.08 | 0.83 | 1.42 |

| 12 to 24 months | 1.46 | 1.11 | 1.93 |

| 24 to 36 months | 0.92 | 0.71 | 1.21 |

| 36 to 48 months | 1.49 | 1.17 | 1.92 |

| TS gain velocity2 | |||

| 0 -18 months | 1.09 | 0.79 | 1.51 |

| 18- 36 months | 1.13 | 0.84 | 1.49 |

| 36-48 months | 1.45 | 1.09 | 1.92 |

| SS gain velocity2 | |||

| 0 -18 months | 1.02 | 0.70 | 1.48 |

| 18- 36 months | 1.26 | 0.97 | 1.65 |

| 36-48 months | 1.43 | 1.09 | 1.88 |

All models adjusted for maternal age, parity, education level, height, BMI, ethnicity and blood pressure. Growth velocities at later periods were additionally adjusted for growth velocities at preceding intervals as well as measurement at birth

BMI=body mass index; AC=abdominal circumference; TS=triceps skinfolds; SS=subscapular skinfolds

Sensitivity analyses

Similar patterns of association were noted when the analyses were re-ran using age- and sex-specific z-scores for height, BMI, AC, TS and SS across the same intervals for the outcomes of BP (Supplementary Table 6), BP z-score (Supplementary Table 7) and prehypertension/hypertension (Supplementary Table 8). The sensitivity analyses showed that faster BMI and adiposity velocities (AC, TS or SS velocities) at age 36 to 48 months, but not at earlier intervals in the first 36 months, are predictive of BP and prehypertension/hypertension risk at 48 months.

Discussion

We found significant associations between timing of BMI and adiposity gains with BP later in childhood. Children who gained BMI and adiposity (AC, TS or SS) at a faster rate than their peers, especially at age 36 to 48 months, had higher mean BPs and risk of prehypertension/hypertension. These associations remained when BP was analyzed as age-, sex- and height-specific z-scores, suggesting that the observed relationship between BMI and adiposity velocity with child BP is independent of the child’s attained height. There have been speculations and hypotheses that early life adiposity gain may exert significant influence on BP later in life (6). Our results however, add to the evidence that BP is more associated with recent adiposity gain rather than adiposity gain during earlier ages, where we demonstrated that changes in BMI and adiposity at various intervals in the first 36 months were not associated with later BP. In comparison, height gains at all intervals showed no significant associations with BP z-score at age 48 months, suggesting that effects of height gains on later BP may be channeled through final attained height. We also found no evidence of effect modification by sex, ethnicity or birth weight. The stronger effect sizes on BP observed at age 36 to 48 months is consistent with recent investigations (7, 10, 14, 28), that showed gains closer to age of BP measurement was a stronger predictor of future BP than were gains in earlier periods. Given that we analyzed growth as rate of change per month across the different periods rather than absolute change, the stronger late effects we observed are not due to the longer period of growth during late infancy and early childhood compared to early infancy.

Our findings are in line with those from cohort studies in Belarus, the United States and the UK. Positive associations between weight gain at ages 3-12 and 12-60 months with child BP at 6.5 years were observed in a cohort of healthy, term children in Belarus, with stronger effect sizes observed during later periods of weight gain closer to 5 years (10). In Project Viva, an ongoing US birth cohort, BMI gain between 2 and 3 years was found to be associated with higher SBP during mid-childhood (6-10 years), with no evidence of effect modification by birth weight (14). A study of 761 infants in the Southampton Women’s Survey reported that greater weight gains between 12-24 and 24-36 months were associated with higher SBP and DBP at 3 years (9). In addition, Chiolero et al noted that weight gains during any age period after birth have substantial impact on BP during childhood and adolescence, with BP being more responsive to recent compared to earlier weight changes (28). Positive associations between weight gain at ages 1 to 5 years (13), and 2 to 4 years (29) with adult BP have also been reported. The stronger size of the associations observed between adiposity velocities and later BP, closer to the age of BP measurement, appear to contrast with Singhal’s “growth acceleration” hypothesis, which found that early infancy weight gain was associated with later BP (6).

Relatively little is known on the role of adiposity gain during infancy and early childhood, on later childhood BP. Higher AC, TS and SS gain at age 36 to 48 months (which reflect central, peripheral and truncal fat deposition, respectively) were found to be associated with child BP in our cohort. Nowson et al had reported that greater conditional gains in AC and subscapular skinfolds during early childhood were associated with higher BP at 3-years (9). A recent cross-sectional survey of school children aged 7-17 years in China reported that those with higher skinfold thicknesses had significantly higher BPs than those with lower skinfold thicknesses (30). Fat mass and waist circumference were also found to be positively and significantly associated with absolute blood pressure and hypertension in a cohort of African-American and European-American children (31). Fat mass is a strong determinant of BP in both children (32) and adults (33). Fat distribution as a risk factor for elevated BP is also well-documented, for central (30, 34), truncal (35) and peripheral fat (34). The positive relationship between accelerated AC, TS and SS velocities with later BP suggests that additional measurements of AC or skinfolds during childhood may be useful to identify children at risk of elevated BP later in life.

Only one study has investigated the relationship between timing of child growth with later BP explicitly in Asian populations(12), where the risk of metabolic disease is higher than in Western populations(15). A longitudinal study of a Hong Kong Chinese cohort reported that growth faltering in ponderal index from 6 to 18 months was inversely associated with systolic blood pressure in adult life(12). However, this was attributed to poor nutrition and environmental conditions at the time of the study. Our study findings are consistent with other studies in Western cohorts, as the socioeconomic settings are similar in Singapore.

Strengths of our study include its prospective design, which is essential to assess the relationship between infant and childhood BMI and adiposity velocities with later BP. To date, only one study has explicitly assessed this relationship in Asian populations. Our study also benefited from detailed anthropometric measures at multiple time points, allowing us to elucidate the associations between the timing of infant and early childhood adiposity velocities and later BP. Limitations to consider include the fact that some children in our cohort did not have their 48-month BP measured, although no differences in baseline characteristics were observed between those with and without measured BP. Secondly, child BP was measured using the Dinamap device, which may have overestimated BP compared with the manual method of measurement (36, 37). Reference values published by the American Academy of Pediatrics are based on manual BP measurement (23), and standardization of BP using this reference may therefore have led to an overestimation of BP z-scores and false-positive diagnosis of prehypertension/hypertension. However, as we also analyzed BP as a continuous variable, we expect the relative rank of individual BP measurements to be preserved. Lastly, our study lacked other cardiovascular risk markers such as plasma insulin, triglyceride and C-peptide, which would be helpful in understanding the associations we observed.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that accelerated BMI and adiposity gains only at the preceding interval before 48 months (age 36 to 48 months), but not at earlier intervals in the first 36 months, are predictive of BP and prehypertension/hypertension risk at 48 months. Our results add to the evidence that BP is more responsive to recent compared to earlier BMI and adiposity velocities, and provide impetus that measures of adiposity gain may be a useful predictor of elevated BP later in childhood. Interventions that could contribute to the management of accelerated adiposity gain, such as targeting modifiable prenatal factors (e.g. gestational weight gain (38), gestational hyperglycemia (39)), other dietary changes, or increases in physical activity may be useful to reduce the risks of elevated BP and related cardiovascular outcomes later in life.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available at International Journal of Obesity’s website

Acknowledgements

The GUSTO study group includes Allan Sheppard, Amutha Chinnadurai, Anne Eng Neo Goh, Anne Rifkin-Graboi, Anqi Qiu, Arijit Biswas, Bee Wah Lee, Birit F.P. Broekman, Boon Long Quah, Borys Shuter, Carolina Un Lam, Chai Kiat Chng, Cheryl Ngo, Choon Looi Bong, Christiani Jeyakumar Henry, Claudia Chi, Cornelia Yin Ing Chee, Yam Thiam Daniel Goh, Doris Fok, E Shyong Tai, Elaine Tham, Elaine Quah Phaik Ling, Evelyn Xiu Ling Loo, Falk Mueller- Riemenschneider, George Seow Heong Yeo, Helen Chen, Heng Hao Tan, Hugo P S van Bever, Iliana Magiati, Inez Bik Yun Wong, Ivy Yee-Man Lau, Jeevesh Kapur, Jenny L. Richmond, Jerry Kok Yen Chan, Joanna D. Holbrook, Joanne Yoong, Joao N. Ferreira, Jonathan Tze Liang Choo, Joshua J. Gooley, Kenneth Kwek, Kok Hian Tan, Krishnamoorthy Niduvaje, Kuan Jin Lee, Leher Singh, Lieng Hsi Ling, Lin Lin Su, Lourdes Mary Daniel, Lynette Pei-Chi Shek, Marielle V. Fortier, Mark Hanson, Mary Foong-Fong Chong, Mary Rauff, Mei Chien Chua, Melvin Khee-Shing Leow, Michael Meaney, Neerja Karnani, Ngee Lek, Oon Hoe Teoh, P. C. Wong, Paulin Tay Straughan, Pratibha Agarwal, Queenie Ling Jun Li, Rob M. van Dam, Salome A. Rebello, See Ling Loy, S. Sendhil Velan, Seng Bin Ang, Shang Chee Chong, Sharon Ng, Shiao-Yng Chan, Shirong Cai, Sok Bee Lim, Stella Tsotsi, Chin-Ying Stephen Hsu, Sue Anne Toh, Swee Chye Quek, Victor Samuel Rajadurai, Walter Stunkel, Wayne Cutfield, Wee Meng Han, Yin Bun Cheung, Yiong Huak Chan, and Zhongwei Huang.

Funding

This study is under Translational Clinical Research (TCR) Flagship Programme on Developmental Pathways to Metabolic Disease, NMRC/TCR/004-NUS/2008; NMRC/TCR/012-NUHS/2014 funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and administered by the National Medical Research Council (NMRC), Singapore. KMG is supported by the National Institute for Health Research through the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), project EarlyNutrition under grant agreement n°289346.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Keith M Godfrey, Yap Seng Chong and Yung Seng Lee have received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products. Keith M Godfrey and Yap Seng Chong are part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbot Nutrition, Nestec and Danone. The remaining authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Clinical Trial Registration

This study is registered under the Clinical Trials identifier NCT01174875; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01174875?term=GUSTO&rank=2

References

- 1.Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dans A, Ng N, Varghese C, Tai ES, Firestone R, Bonita R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in southeast Asia: time for action. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):680–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61506-1. Epub 2011 Jan 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahern D, Dixon E. Pediatric Hypertension: A Growing Problem. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2015;42(1):143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauer RM, Clarke WR. Childhood risk factors for high adult blood pressure: the Muscatine Study. Pediatrics. 1989 Oct;84(4):633–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels SR, Pratt CA, Hayman LL. Reduction of risk for cardiovascular disease in children and adolescents. Circulation. 2011 Oct 11;124(15):1673–86. doi: 10.161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.016170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singhal A, Cole TJ, Fewtrell M, Deanfield J, Lucas A. Is slower early growth beneficial for long-term cardiovascular health? Circulation. 2004 Mar 9;109(9):1108–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118500.23649.DF. Epub 2004 Mar 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones A, Charakida M, Falaschetti E, Hingorani AD, Finer N, Masi S, et al. Adipose and height growth through childhood and blood pressure status in a large prospective cohort study. Hypertension. 2012 May;59(5):919–25. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187716. Epub 2012 Apr 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lurbe E, Garcia-Vicent C, Torro MI, Aguilar F, Redon J. Associations of birth weight and postnatal weight gain with cardiometabolic risk parameters at 5 years of age. Hypertension. 2014 Jun;63(6):1326–32. doi: 10.161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03137. Epub 2014 Mar 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowson CA, Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Godfrey KM, Lawrence WT, Law CM, et al. Association of early childhood abdominal circumference and weight gain with blood pressure at 36 months of age: secondary analysis of data from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014 Jul 3;4(7):e005412. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005412. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-. Epidemiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilling K, Davies N, Windmeijer F, Kramer MS, Bogdanovich N, Matush L, et al. Is infant weight associated with childhood blood pressure? Analysis of the Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2011 Oct;40(5):1227–37. doi: 10.093/ije/dyr119. Epub 2011 Sep 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Primatesta P, Falaschetti E, Poulter NR. Birth weight and blood pressure in childhood: results from the Health Survey for England. Hypertension. 2005 Jan;45(1):75–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150037.98835.10. Epub 2004 Nov 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung YB, Low L, Osmond C, Barker D, Karlberg J. Fetal growth and early postnatal growth are related to blood pressure in adults. Hypertension. 2000 Nov;36(5):795–800. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law CM, Shiell AW, Newsome CA, Syddall HE, Shinebourne EA, Fayers PM, et al. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth and adult blood pressure: a longitudinal study from birth to 22 years of age. Circulation. 2002 Mar 5;105(9):1088–92. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perng W, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kramer MS, Haugaard LK, Oken E, Gillman MW, et al. Early Weight Gain, Linear Growth, and Mid-Childhood Blood Pressure: A Prospective Study in Project Viva. Hypertension. 2016 Feb;67(2):301–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06635. Epub 2015 Dec 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurpad AV, Varadharajan KS, Aeberli I. The thin-fat phenotype and global metabolic disease risk. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011 Nov;14(6):542–7. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834b6e5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soh SE, Chong YS, Kwek K, Saw SM, Meaney MJ, Gluckman PD, et al. Insights from the Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort study. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64(3–4):218–25. doi: 10.1159/000365023. Epub 2014 Oct 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soh SE, Tint MT, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Rifkin-Graboi A, Chan YH, et al. Cohort profile: Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) birth cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014 Oct;43(5):1401–9. doi: 10.093/ije/dyt125. Epub 2013 Aug 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 Aug 1;174(3):253–60. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193. Epub 2011 Jul 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leppik A, Jurimae T, Jurimae J. Reproducibility of anthropometric measurements in children: a longitudinal study. Anthropol Anz. 2004 Mar;62(1):79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim WY, Lee YS, Yap FK, Aris IM, Ngee L, Meaney M, et al. Maternal Blood Pressure During Pregnancy and Early Childhood Blood Pressures in the Offspring: The GUSTO Birth Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015 Nov;94(45):e1981. doi: 10.097/MD.0000000000001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Aguayo A, Aglony M, Bancalari R, Avalos C, Bolte L, Garcia H, et al. Birth weight is inversely associated with blood pressure and serum aldosterone and cortisol levels in children. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012 May;76(5):713–8. doi: 10.1111/j.365-2265.011.04308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Aguayo A, Aglony M, Campino C, Garcia H, Bancalari R, Bolte L, et al. Aldosterone, plasma Renin activity, and aldosterone/renin ratio in a normotensive healthy pediatric population. Hypertension. 2010 Sep;56(3):391–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155135. Epub 2010 Aug 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004 Aug;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tu YK, Tilling K, Sterne JA, Gilthorpe MS. A critical evaluation of statistical approaches to examining the role of growth trajectories in the developmental origins of health and disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2013 Oct;42(5):1327–39. doi: 10.093/ije/dyt157. Epub 2013 Sep 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cruickshank JK, Mzayek F, Liu L, Kieltyka L, Sherwin R, Webber LS, et al. Origins of the "black/white" difference in blood pressure: roles of birth weight, postnatal growth, early blood pressure, and adolescent body size: the Bogalusa heart study. Circulation. 2005 Apr 19;111(15):1932–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161960.78745.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauer RM, Anderson AR, Beaglehole R, Burns TL. Factors related to tracking of blood pressure in children. U.S. National Center for Health Statistics Health Examination Surveys Cycles II and III. Hypertension. 1984 May-Jun;6(3):307–14. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.6.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Onis M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006 Apr;450:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiolero A, Paradis G, Madeleine G, Hanley JA, Paccaud F, Bovet P. Birth weight, weight change, and blood pressure during childhood and adolescence: a school-based multiple cohort study. J Hypertens. 2011 Oct;29(10):1871–9. doi: 10.097/HJH.0b013e32834ae396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adair LS, Martorell R, Stein AD, Hallal PC, Sachdev HS, Prabhakaran D, et al. Size at birth, weight gain in infancy and childhood, and adult blood pressure in 5 low- and middle-income-country cohorts: when does weight gain matter? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 May;89(5):1383–92. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27139. Epub 2009 Mar 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang YX, Wang SR. Distribution of subcutaneous fat and the relationship with blood pressure in obese children and adolescents in Shandong, China. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015 Mar;29(2):156–61. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12178. Epub 2015 Feb 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willig AL, Casazza K, Dulin-Keita A, Franklin FA, Amaya M, Fernandez JR. Adjusting adiposity and body weight measurements for height alters the relationship with blood pressure in children. Am J Hypertens. 2010 Aug;23(8):904–10. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.82. Epub Apr 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drozdz D, Kwinta P, Korohoda P, Pietrzyk JA, Drozdz M, Sancewicz-Pach K. Correlation between fat mass and blood pressure in healthy children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009 Sep;24(9):1735–40. doi: 10.007/s00467-009-1207-9. Epub 2009 May 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siervogel RM, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Morris JG, Webb P, Knittle JL. Blood pressure, body composition, and fat tissue cellularity in adults. Hypertension. 1982 May-Jun;4(3):382–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shear CL, Freedman DS, Burke GL, Harsha DW, Berenson GS. Body fat patterning and blood pressure in children and young adults. The Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 1987 Mar;9(3):236–44. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He Q, Horlick M, Fedun B, Wang J, Pierson RN, Jr, Heshka S, et al. Trunk fat and blood pressure in children through puberty. Circulation. 2002 Mar 5;105(9):1093–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flynn JT, Pierce CB, Miller ER, 3rd, Charleston J, Samuels JA, Kupferman J, et al. Reliability of resting blood pressure measurement and classification using an oscillometric device in children with chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr. 2012 Mar;160(3):434–40.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.071. Epub Nov 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whincup PH, Bruce NG, Cook DG, Shaper AG. The Dinamap 1846SX automated blood pressure recorder: comparison with the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer under field conditions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992 Apr;46(2):164–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hivert MF, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Oken E. Greater early and mid-pregnancy gestational weight gains are associated with excess adiposity in mid-childhood. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016 Jul;24(7):1546–53. doi: 10.002/oby.21511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aris IM, Soh SE, Tint MT, Saw SM, Rajadurai VS, Godfrey KM, et al. Associations of gestational glycemia and prepregnancy adiposity with offspring growth and adiposity in an Asian population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Nov;102(5):1104–12. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.117614. Epub 2015 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.