Abstract

Background:

The literature on international medical graduates (IMGs) in Canada is growing, but there is a lack of systematic analysis of the literature.

Objectives:

To examine (1) the major themes in academic and grey literature pertaining to professional integration of IMGs in Canada; and (2) the gaps in our knowledge on integration of IMGs.

Methods:

This paper is based on the scoping review of academic and grey literature published during 2001–2013 about IMGs in Canada.

Results:

The literature on IMGs focuses on (1) pre-immigration activities; (2) early-arrival activities; (3) credential recognition/professional recertification; (4) bridging and residency training; (5) workplace integration; and (6) alternative paths to integration. The gaps in the literature include pre-immigration and early-arrival activities, and alternative paths for integration for those IMGs who do not pursue medical license.

Conclusion:

Pre-immigration and early-arrival activities and alternative career paths for IMGs should be addressed in academic and policy research.

Abstract

Contexte:

Il existe de plus en plus de littérature sur les diplômés internationaux en médecine (DIM) au Canada, mais il y a un manque d'analyse systématique de cette littérature.

Objectifs:

Examiner (1) les principaux thèmes de la littérature scientifique et grise au sujet de l'intégration professionnelle des DIM au Canada; et (2) les lacunes en matière de connaissances sur l'intégration des DIM.

Méthode:

Cet article se fonde sur un examen de portée de la littérature scientifique et grise sur les DIM au Canada publiée entre 2001 et 2013.

Résultats:

La littérature sur les DIM porte principalement sur (1) les activités avant l'immigration et (2) dans les premiers temps après l'arrivée; (3) la reconnaissances des titres de compétence/la recertification professionnelle; (4) la formation de transition et en résidence; (5) l'intégration au milieu de travail; et (6) les autres parcours d'intégration. Les lacunes de la littérature touchent aux activités avant l'immigration et dans les premiers temps après l'arrivée ainsi qu'aux autres parcours d'intégration pour les DIM qui ne convoitent pas un permis de pratique médicale.

Conclusion:

Les activités avant l'immigration et dans les premiers temps après l'arrivée, ainsi que les autres parcours de carrière, devraient faire l'objet de recherches universitaires et politiques.

Introduction

The status of international medical graduates (IMGs) and the role they play in provincial and territorial health systems have been a consistent topic within public and policy dialogues for over a decade. On the one hand, IMGs are seen as a pool of highly skilled professionals, who, with the right assessment and/or upgraded training, can practise medicine in Canada. On the other hand, concerns about the ethical aspects of recruiting IMGs have been raised with the corollary focus on domestic production towards the goal of self-sufficiency (ACHDHR 2009). Reflecting these tensions has been a growing literature on the role of IMGs in Canada. Synthesizing this literature is both timely and necessary for informed policy making.

This paper summarizes the key findings from the knowledge synthesis conducted by the Canadian Health Human Resources Network (CHHRN) on the role of Internationally Educated Health Professionals (IEHPs) in Canada with a focus on IMGs. Specifically, it synthesizes the existing academic and grey literature on the professional integration of IMGs in Canada and addresses the following questions:

What are the major themes in the academic and grey literature pertaining to professional integration of IMGs in Canada?

What are the gaps in our knowledge on integration of IMGs that can be addressed in policy and research?

Generating this knowledge can help inform better health human resources policies.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of academic and grey literature about IMGs in Canada as part of a large review of IEHPs. Our work was guided by an updated version of Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) six-step methodological framework for scoping reviews. Using the keywords (alone and in combination) physicians, foreign-trained, foreign-graduate, international medical graduate, health professionals, internationally educated, migrant, immigrant and Canada, we searched CINHAL, EMBASE and PubMed electronic databases for academic and peer-reviewed literature that was published from 2001 to 2013 about IMGs in Canada. The same keywords' strategy was used to identify grey literature via the Canadian Electronic Library and the Canadian Health Human Resources Network (CHHRN) Library – an online repository of academic and grey literature on health human resources in Canada. We also conducted Internet searches of federal, provincial and territorial governments and professional and immigrant associations' websites and hand-searched the bibliographic information of both the grey and academic literature. Both French and English sources were collected for the analysis.

An advisory council of stakeholders (experts from academia, government and professional organizations on the integration of IEHPs [and IMGs]) was consulted throughout the project and near the conclusion. The stakeholders recommended additional literature not identified in the formal searches and provided feedback that we used to interpret the findings.

To be included in the analysis, the identified sources had to be about IMGs in Canada, published during 2000–2013, and written in either English or French. We reviewed the abstract (or first page/executive summary) of each source to ensure it followed our inclusion criteria. Our coding scheme was developed inductively from the literature (Bradley et al. 2007) and was operationalized in the form of a literature extraction tool created in Microsoft Excel. A team of five researchers worked on the coding scheme and analysis using the literature extraction tool. Each source was coded under one of the following six major themes: pre-immigration activities, early arrival, credential recognition and professional recertification, bridging and residency, workforce integration and alternative paths to integration, and, if warranted, under one or more minor themes. To confirm the reliability of the coding scheme, each investigator independently coded 10 sources (Zhang and Wildemuth 2009). We then compared our results and discussed discrepancies in our coding until consensus was reached; we refined our coding scheme accordingly (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006).

Results

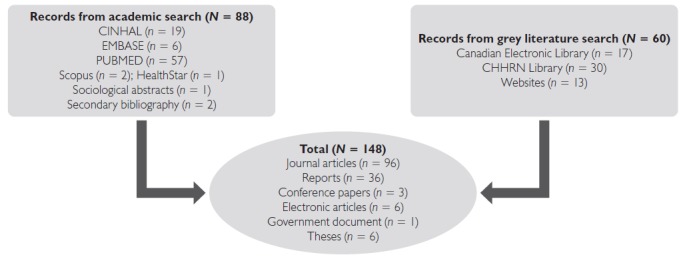

In total, 148 sources were retained for analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search

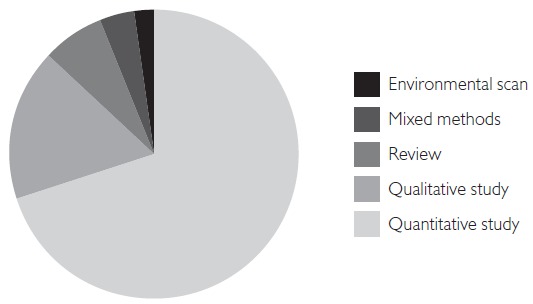

Articles in academic journals were the most common source for information about IMGs (N = 96). They were followed by academic and government-issued reports (N = 36). More than half (58.1%) of the literature summarized empirical studies (see Figure 2 for breakdown of empirical methods used).

Figure 2.

Empirical studies (N = 86)

Over half of all literature (55%) was focused on Canada in general or multiple jurisdictions across Canada. This was followed by the literature focused specifically on the provinces of Ontario (14%, N = 21), British Columbia (8%, N = 12) and Alberta (7%, N = 11). The rest of the provinces and territories were discussed much less often (each <5%).

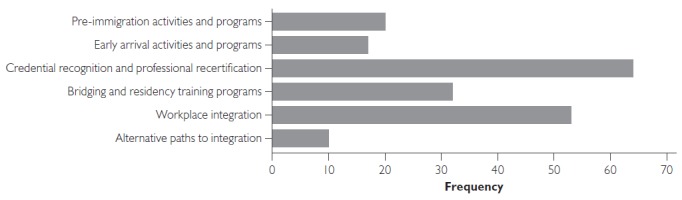

We found that the literature on IMGs can be broadly mapped into the following six major categories: (1) pre-immigration activities and programs; (2) early-arrival activities; (3) credential recognition and professional recertification; (4) bridging and residency training programs; (5) workforce integration; and (6) alternative paths to integration. Because some sources were coded in more than one theme, a total of 196 sources were coded in these thematic categories (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency of thematic categories of the Canadian IMG literature

IMG = international medical graduate.

In what follows, we provide a brief overview of each of the major themes, identify gaps in our knowledge and offer recommendations for research and policy.

Pre-immigration Activities and Programs

In this thematic category, we coded the literature that examined the recruitment of IMGs, push and pull factors that drive IMGs to leave their home country and/or choose Canada as a country of destination, and the activities that are or should be undertaken before IMGs arrive in Canada to facilitate the process of professional integration. In terms of the push and pull factors that motivate physicians to move to Canada, most of the literature links the decision to immigrate to the poor economic and social conditions that IMGs experience in their home country (de Carvalho 2007; Klein et al. 2009). It seems that Canada is chosen by IMGs because of its political and economic stability, professional opportunities and personal considerations (Bourgeault et al. 2010). Other than noting these factors, the literature does little to enumerate which of these factors are the most important causes for either push or pull.

The literature does, however, problematize the “pull” factors. Much of it condemns the practice of “poaching” physicians from abroad, finding it ethically problematic (College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario 2010; Dauphinee 2005). It is also evident that the gaps in the distribution of physicians have driven many provinces to recruit physicians from abroad (Audas et al. 2004; Physician Recruitment Agency of Saskatchewan 2012; Shuchman 2008; Urowitz et al. 2008). Finally, some literature explores the implications of poor health human resources (HHR) planning and “boom–bust cycles”, where the perceived shortages of physicians are followed by the cycles of perceived oversupply (Dauphinee 2005; Deber 2010).

The literature also examines IMGs' pre-arrival activities or lack thereof. The Foreign Credentials Referral Office (2011), for example, notes the importance of initiating the process of professional recognition early. Although the Medical Council of Canada offers Evaluating Examination (MCCEE) at more than 500 centres worldwide (Medical Council of Canada 2010), at the time of the review only about half of IMGs attempted to write it before arriving in Canada. This may be because some newcomers are led to believe that the immigration point system that is implemented to assess their eligibility to immigrate to Canada reflects their employability (de Carvalho 2007). Therefore, many are disillusioned once they arrive in Canada and begin the process of professional integration (Neiterman and Bourgeault 2012).

Early-arrival Activities and Integration Programs

Only a relatively small proportion (8.67%) of the literature addressed the particular immigration route that IMGs took and the role of government organizations, settlement agencies and professional associations in facilitating the process of professional integration of IMGs early in their arrival process. Generally, the literature suggests that, upon arrival, IMGs are often experiencing confusion and lack of knowledge about the system navigation in Canada, which can result in unnecessary delays in the process of professional recertification (Bourgeault et al. 2010). In addition to these issues, one of the major barriers for professional recertification is a financial one (Johnson and Baumai 2011). Overall, the reports from the literature indicate that physicians recruited under Provincial Nominee Programs or those holding provisional licenses are more rapidly integrated than those who arrive as skilled workers (or through other immigration categories, such as family class or refugees) and are trying to certify independently (Johnson and Baumai 2011). The literature also raises concerns about physicians' “brain waste” and calls for better integration between federal and provincial immigration/labour policies (Dove 2009; Nelson et al. 2011). To address this problem, some provincial programs subsidize IEHPs by repaying up to 50% licensure process costs (Prince Edward Island ANC 2011).

Although the importance of providing support to the newcomer IEHPs is recognized in research and policy, the literature discusses only a handful of government programs and organizations that cater to the needs of newly arrived healthcare professionals (Health Force Ontario 2012; Jablonski 2012). Generally, such programs and organizations have been found to be very effective and highly beneficial to the integration of IMGs. For instance, the Access Centre for Internationally Educated Health Care Professionals run by Health Force Ontario (2012) addresses the needs of newly arrived IMGs and other IEHPs by providing counselling, orientation and information services, as well as some on-site courses. The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada provides training to IMGs and their teachers about the experiences of IMGs and the challenges on their route to professional integration (Armson and Crutcher 2006). Many services are also offered by local associations of immigrant physicians, such as the Association of International Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (AIPSO) or Alberta International Medical Graduates Association (AIMGA) (AIPSO 2013; Bobrosky 2010; McMahon 2009). These organizations may also advocate on behalf of IMGs with provincial governments (AIPSO 2000; McMahon 2009). These efforts notwithstanding, the literature on early-arrival activities and system navigation is not particularly rich, and we need to learn more about the experiences of IMGs upon their arrival in Canada.

Credential Recognition and Professional Recertification

In this largest thematic category (32.7%, N = 64), the literature focused on credential recognition, national examinations, Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) and various barriers that may complicate the process of licensure for IMGs. Most of this literature discusses the many challenges experienced by IMGs, including credential verification, financial barriers, limited assessment options and (lack of) bridging opportunities; however, the key challenge for IMGs at this juncture seems to be the national licensure examinations (Boyd and Shellenberg 2008; Kogo 2012; Office of the Fairness Commissioner 2009; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 2013). Canadian Medical Graduates (CMGs) significantly outperform IMGs on the Medical Council of Canada professional exams (MCCEQ1 and MCCEQ2) (MCC 2013). CMGs also do much better than IMGs on the certification examinations of the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) (e.g., 90.4% versus 66% for 2007) and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (95% versus 75% for 2005–2009) (Walsh et al. 2011). The reasons for these differences have been attributed to IMGs' unfamiliarity with such types of examinations (MacLellan et al. 2010; Peters 2013; Vallevand and Violato 2012), problems with communication skills and different training (Baig et al. 2009; Peters 2013), as well as financial burden, problems with self-esteem and cultural competency (Bourgeault et al. 2010; Sharieff and Zakus 2006).

The Medical Council of Canada Evaluating Examination (MCCEE) received the most controversy in the literature because this exam has been written only by IMGs as a prerequisite for regular examinations (Boyd and Shellenberg 2008). Some IMGs suggested that this examination is expensive and discriminatory (Ahmed 2003; AIPSO 2013). It is worth to note, however, that there is significant correlation between IMGs' success on the MCCEE and their subsequent performance on MCC and certifying examinations – there is 70% more likelihood of passing MCC qualifying exams for IMGs who passed the MCCEE on their first attempt (McMahon 2009). The fact that Canadians Studying Medicine Abroad (CSAs) and some IMGs have a much higher passing rate of the MCCEE than others suggests that medical school and culture play a role in the success at the MCCEE (McMahon 2009). A number of studies note that racial and ethnic background and the country of graduation can determine one's likelihood of receiving professional license (Boyd and Shellenberg 2008; Foster 2008; McDonald and Worswick 2010).

The need to achieve some national standards for assessment of IMGs' training and education has been recognized by federal and provincial stakeholders, including the Federation of Medical Regulatory Authorities of Canada (FMRAC), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) and the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC). In 2009, the Pan-Canadian Framework for the Assessment and Recognition of Foreign Qualifications was established with a promise to assess medical education starting 2012, with the goal to streamline the process of credential assessment for IMGs in Canada (McMahon 2009). The literature identifies other promising practices, such as an establishment of national Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) and the new electronic process that simplifies the application for licensure for IMGs by allowing immigrant physicians to apply to all provinces simultaneously (Doyle 2010). The report of the IMGs national database provides statistics and data for IMGs' registration for each province (AFMCC 2006).

In sum, IMGs face cultural, financial, structural and organizational barriers during the process of professional integration (Banner et al. 2013; Neiterman and Bourgeault 2012). The literature highlights the sense of confusion that IMGs report when navigating the system (Matejicek 2009; Wong and Lohfeld 2008). Policy makers are evidently aware of these challenges and work towards streamlining the process of credential recognition for IMGs (Bowmer 2005; Canadian Medical Association 2008; Doyle 2010; Masalmeh 2009).

Bridging Programs & Residency Training

A small proportion of literature on IMGs (16.3%) examined the bridging programs and residency training available to immigrant physicians. The number of IMGs entering postgraduate residency positions increased from 77 in 2000 to 407 in 2012, over a 528% increase (CaRMS 2013), but IMGs are still less likely to obtain residency training than CMGs (Table 1). It is interesting to note that one of the key bottlenecks to IMG integration – securing a residency – while certainly present, is not reflected in the frequency of its treatment in the literature.

Table 1.

CaRMS results for IMGs 2006–2012

| Year | IMG participation | Match results | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 932 | 111 | 11.9 |

| 2007 | 1,125 | 69 | 6.2 |

| 2008 | 1,299 | 305 | 23.5 |

| 2009 | 1,387 | 294 | 21.2 |

| 2010 | 1,497 | 274 | 18.3 |

| 2011 | 1,920 | 380 | 19.8 |

| 2012 | 2,156 | 407 | 18.9 |

CaRMS = Canadian Resident Matching Service; IMG = international medical graduate. Source: CaRMS 2013.

In addition to the notable difficulties in obtaining residency positions, IMGs also face challenges once in residency. These include cultural or ethnic discrimination (Bates and Andrew 2001; Crutcher et al. 2011), lack of cultural capital and communication barriers (Allan et al. 2007; Childs and Herbert 2007; Jain et al. 2012). To address the challenges faced by IMGs in residency, some provinces established mandatory or voluntary pre-residency educational and/or bridging programs (Curran et al. 2008; Stenerson et al. 2009). For instance, in Ontario, a four-month program for family medicine residents is offered through the Centre for the Evaluation of Health Professionals Educated Abroad (CEHPEA, now referred to as the Touchstone Institute) (Thomson and Cohl 2011).

A growing body of literature focuses on the Canadian students studying in overseas medical schools (CSAs). The number of CSAs is reported to be as high as 3,600 (Dhalla 2011). Literature suggests that CSAs typically study in the Caribbean, Ireland and the UK and that >90% of CSAs plan to return to Canada for residency training (Banner et al. 2013; Keenan 2005). The voices of CSAs reflected in the literature call for a distinct path for integration that would recognize their unique set of skills and qualifications (Evangelista 2000; Keenan 2005; Violato et al. 2011).

Workplace Integration

The second largest category of the literature on IMGs (27%, N = 53) examines the integration and retention of IMGs, their mobility after licensure and their adaptation to the Canadian clinical practice. The literature on workplace integration identifies a number of facilitating factors that contribute to retention of IMGs. These include successful workplace and social integration, difficulties in obtaining full license, remuneration and (if applicable) spouse's satisfaction (Kogo 2012; Mayo and Mathews 2006). Clearly, larger social integration is a key factor for the successful retention of IMGs (Curran 2008).

While IMGs are often recruited to underserviced/rural areas, the literature suggests that they do not provide long-term sustainability to rural practice, as they tend to move to urban centres once fully certified (Audas et al. 2009; Landry et al. 2010; Mathews et al. 2008). Evidently, IMGs follow the patterns of interprovincial migration of CMGs (Dauphinee 2006; Watanabe 2008). In addition to interprovincial migration, a small proportion of IMGs (<1% throughout 1995–2005) is leaving Canada to go back to their home countries or to the US (Watanabe 2008). Approximately one-third of these IMGs return to Canada within five years, which suggests complex and non-linear health workforce migration paths.

Literature also examines the differences and similarities between CMGs' and IMGs' clinical practice. It was found that IMGs and CMGs differ in the rates of referrals to some medical tests (colonoscopy), provision of preventative and maternity care, and prescription of antibiotics and other medications (Cadieux et al. 2007; Jacob et al. 2011; Thind et al. 2007, 2008). In general, literature is dominated by the focus on the location of IMGs' practice and not the content of their clinical work.

Alternative Paths to Integration

There is very little information available about IMGs who have not been certified as physicians in Canada. It is estimated that in 2006, there were almost 14,500 such individuals in Canada (McDonald and Worswick 2010). Given that so many IMGs are unable to integrate professionally in Canada for various personal and structural reasons, it is of concern that we know so little about the alternative paths for integration of IMGs. Only 10 sources were coded in this thematic category, most of which focused on what should be done (as opposed to what is done) to provide IMGs with alternative employment opportunities (Broten 2008). The physician assistant (PA) programs have been found to be popular among IMGs (Bhimji 2010; Magnus 2008); however, representatives of PA programs are reluctant to accept IMGs as students because they are often construed as choosing PA training as a transition stage (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006).

Discussion

The goals of this research were to consolidate the growing literature on IMGs, identify knowledge gaps and provide recommendations for policy and research. Overall, the literature on IMGs is generated by academics, policy makers, professional associations and government bodies and is unevenly spread across Canadian provinces. The key themes identified in our analysis follow the trajectory of professional integration of IMGs from arrival planning to workplace integration (or alternative paths for employment).

Our findings on the state of knowledge about IMGs in Canada are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

State of knowledge on IMGs in Canada

| What we know | Gaps in research and policy |

|---|---|

| Push/pull factors model is often used to explain international mobility of IMGs | Which push/pull factors are most critical for migration-related decision-making? |

| Pre- and early arrival activities and programs facilitate professional integration | How to improve accessibility of pre-and early arrival activities and programs for IMGs? |

| Professional integration remains a challenge for IMGs | What is our state of knowledge about the access to residency training for IMGs? |

| Compared to CMGs, IMGs do not do well on professional examinations | How to ensure that current licensure requirements are transparent and not informed by practices that could be considered discriminatory? |

| Thousands of IMGs are not successful in obtaining licensure in Canada | What are the alternative career paths for IMGs who are unable to practice medicine? |

CMGs = Canadian medical graduates; IMGs = international medical graduates.

We found that the literature on professional certification and workplace integration dominates the field of research on IMGs. Surprisingly, despite its significance as a key barrier for IMGs' integration, the access to residency training is not discussed in the literature as frequently as other integration themes. We also found that pre-immigration activities and programs and early-arrival activities of IMGs do not receive sufficient attention in the literature and policy. Engaging in pre-arrival and early-arrival activities that facilitate professional licensure has been shown to considerably improve the IMG's professional success (FCRO 2011). Another gap in the literature and policy is the lack of literature about (and, possibly, options for) alternative paths of professional integration for those IMGs who do not pursue medical license. Given that thousands of IMGs do not become licensed physicians, it is important to identify how and where their valuable skills can be utilized.

The systematic, transparent and rigorous methods we used to identify the literature, gaps in evidence and future areas for research, as well as our consultation with community representatives, are major strengths of this review (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). The limitation of our methodological approach is that we did not evaluate the quality of the literature we collected (Grimshaw 2014). Future research can address this by conducting more focused literature synthesis on any of the key themes identified in this review.

In conclusion, we would like to offer a number of recommendations for policy and research. First, there is a need to communicate the importance of pre- and early-arrival activities for IMGs' professional recertification. This includes not only providing IMGs with an opportunity to write professional examinations in their home country but also communicating the pivotal implications of these activities and improving access to early-arrival programs once in Canada. A more contested area for policy discussion is IMGs' demand to reconsider some of the existing requirements for professional integration (e.g., MCCEE). These debates touch upon the fairness of the existing approach and hint at (un)intentional discrimination of internationally trained physicians. Reviewing licensure requirements for IMGs and CSAs may prove useful in making the rationale for their existence more transparent, demonstrating their effectiveness and identifying any redundancies if such exist. Finally, there is a need to pay much more attention in policy and research to IMGs who do not obtain professional license. Providing alternative forms of employment to these highly skilled healthcare professionals can benefit the Canadian healthcare system and give IMGs a sense of fulfillment and a hope that there still is a future for them in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Network Catalyst Grant. We would like to thank Alison Quartaro and Kate Kienapple for their help in conducting this research.

Contributor Information

Elena Neiterman, Lecturer, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON.

Ivy Lynn Bourgeault, Professor, Telfer School of Management, CIHR Research Chair in Gender, Work and Health Human Resources, Lead Coordinator, Canadian Health Human Resource Network @CHHRN, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON.

Christine L. Covell, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

References

- ACHDHR (Advisory Community on Health Delivery and Human Resources). 2009. “How Many Are Enough? Redefining Self-Sufficiency for the Health Workforce – A Discussion Paper.” Retrieved July 5, 2016. <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/alt_formats/pdf/pubs/hhrhs/2009-self-sufficiency-autosuffisance/2009-hme-eng.pdf>.

- Ahmed S.N. 2003. “MCC Evaluating Examination and the International Medical Graduate.” Canadian Medical Association Jounrnal 169(11): 1146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIPSO. 2000. “Barriers to Licensing in Ontario for International Physicians.” Retrieved January 19, 2013. <http://tools.hhr-rhs.ca/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=att_download&link_id=3828&cf_id=68&lang=fr>.

- AIPSO. 2013. “Association of International Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario.” Retrieved January 19, 2013. <http://aipso.webs.com/>.

- Allan G.M., Manca D., Szafran O., Korownyk C. 2007. “EBM a Challenge for International Medical Graduates.” Family Medicine 39(3): 160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Armson H., Crutcher R. 2006. Orienting Teachers and International Medical Graduates. A Faculty Development Program for Teachings of International Medical Graduates. Calgary, AB: The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; Retrieved January 3, 2017. <https://afmc.ca/timg/OTI_en.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada and Canadian Post-M.D. Education Registry (AFMCC). 2006. National IMG Database: Tracking the Acquisition of Canada Credentials and Access to Practice. Preliminary Report 2006. Retrieved May 9, 2017. <http://tools.hhr-rhs.ca/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=viewlink&link_id=6140&Itemid=109&lang=fr>.

- Audas R., Ross A., Vardy D. 2004. The Role of International Medical Graduates in the Provision of Physician Services in Atlantic Canada. St John's, NL: Leslie Harris Centre of Regional Policy and Development, Memorial University. [Google Scholar]

- Audas R., Ryan A., Vardy D. 2009. “Where Did the Doctors Go? A Study of Retention and Migration of Provisionally Licensed International Medical Graduates Practising in Newfoundland and Labrador between 1995 and 2006.” Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 14(1): 21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig L., Violato C., Crutcher R. 2009. “Assessing Clinical Communication Skills in Physicians: Are the Skills Context Specific or Generalizable?” BMC Medical Education 9: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banner S.R., Walsh A., Schabort I., Armson H., Bowmer M.I., Granata B. 2013. International Medical Graduates – Current Issues. Retrieved January 12, 2013. <https://www.afmc.ca/pdf/fmec/05_Walsh_IMG%20Current%20Issues.pdf>.

- Bates J., Andrew R. 2001. “Untangling the Roots of Some IMG's Poor Academic Performance.” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 76(1): 43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhimji A. 2010. “International Medical Graduates: The Medicentres Experience.” Healthcare Papers 10(2): 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrosky W. 2010. Towards Creating a Fair and Equitable Fast Track Assessment Process for Alberta International Medical Graduates. Calgary, AB: The Alberta International Medical Graduates Association (AIMGA). [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeault I.L., Neiterman E., LeBrun J., Viers K., Winkup J. 2010. Brain Gain, Drain & Waste: The Experiences of Internationally Educated Health Professionals in Canada. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa; Retrieved July 5, 2016. <http://www.threesource.ca/documents/February2011/brain_drain.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Bowmer I. 2005. Canadian Initiatives: Assessment and Integration of International Medical Graduates and Other Internationally Educated Health Professionals (IEHP). Retrieved January 24, 2013. <http://rcpsc.medical.org/publicpolicy/documents/2005/9_migration_can.pdf>.

- Boyd M., Shellenberg G. 2008. “Re-Accreditation and the Occcupations of Immigrant Doctors and Engineers.” Canadian Social Trends. Statistics Canada – Catalogue No 11-008.

- Bradley E.H., Curry L.A., Devens K.J. 2007. “Qualitative Data Analysis for Health Services Research: Developing Taxonomy, Themes, and Theory.” Health Services Research 42(4): 1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broten L. 2008. Report on Removing Barriers for International Medial Doctors. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; Retrieved July 5, 2016. <http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.alphaweb.org/resource/collection/E663A143-8C25-4E1B-92E2-B55FE9A61B1B/GBHU_resolution_healthcare_PhysShortage_03-07-2008.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Cadieux G., Tamblyn R., Dauphinee D., Libman M. 2007. “Predictors of Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing among Primary Care Physicians.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 177(8): 877–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO). 2010. Ethical Recruitment of International Medical Graduates. Retrieved November 24, 2010. <http://www.cpso.on.ca/policies/positions/default.aspx?id=1732>.

- Canadian Medical Association. 2008. International Medical Graduates in Canada. Retrieved July 5, 2016. <https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/international-medical-graduates.aspx>.

- CaRMS. 2013. Match Results for International Medical Graduates. Second Iteration R-1 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2013. <http://www.carms.ca/en/data-and-reports/r-1/reports-2014/>.

- Childs R., Herbert M. 2007. Assessing IMG performance at Ontario Medical Schools, 2002–2006: Final Report. Toronto, Ontario: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Crutcher R.A., Szafran O., Woloschuk W., Chatur F., Hansen C. 2011. “Family Medicine Graduates Perceptions of Intimidation, Harassment, and Discrimination during Residency Training.” BMC Medical Education 11: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran V., Hollett A., Hann S., Bradbury C.A. 2008. “A Qualitative Study of the International Medical Graduate and the Orientation Process.” Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 13(4): 163–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho M. 2007. The Implications of Being an International Medical Graduate (IMG) in Canadian Society: A Qualitative Study of Foreign Trained Physicians' Resettlement, Sense of Identity and Health Status. St. Catharines, ON: Brock University; Retrieved July 5, 2016. <https://dr.library.brocku.ca/handle/10464/1381>. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinee W.D. 2005. “Physician Migration to and from Canada: The Challenge of Finding the Ethical and Political Balance between the Individual's Right to Mobility and Recruitment to Underserved Communities.” Journal of Continuing Education in Health Professions 25(1): 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinee W.D. 2005. “The Circle Game: Understanding Physician Migration Patterns within Canada.” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 81(12 Suppl.): S49–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deber R. 2010. “Internationally Educated Workers Jeopardy: Answers and Questions” Healthcare Papers 2(10): 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla I.K.B. 2011. “Why Are so Many Canadians Going Abroad to Study Medicine?” Healthy Deabte. Retrieved June 24, 2013. <http://healthydebate.ca/2011/03/topic/politics-of-health-care/why-are-so-many-canadians-going-abroad-to-study-medicine>.

- Dove N. 2009. “Can International Medical Graduates Help Solve Canada's Shortage of Rural Physicians?” Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 14(3): 120–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle S. 2010. “One-Stop Shopping for International Medical Graduates.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 182(15): 1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista D. R. 2000. “Attitudinal Problems Facing International Medical Graduates.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 163(6): 697–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J., Muir-Cochrane E. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(1): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Foreign Credentials Referral Office (FCRO). 2011. Strengthening Canada's Economy: Government of Canada Progress Report 2011. Retrieved July 05, 2016. <http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/pub/progress-report2011.pdf>.

- Foster L. 2008. “Foriegn Trained Doctors in Canada: Cultural Contingency and Cultural Democracy in the Medical Profession.” International Journal of Criminology and Sociology Theory 1(1): 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J. 2014. A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis. A Knowledge Sythesis Chapter. Retrieved June 12, 2014. <http://www.chir-irsc.gc.ca/e/41382.html>.

- Health Force Ontario. 2012. Working in Ontario. Retrieved January 23, 2012. <http://www.healthforceontario.ca/>.

- Jablonski I. 2012. Employment Status and Professional Integration Outcomes of IMGs in Ontario. Interdisciplinary School of Health Studies. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob B.J., Baxter N.M., Moineddin R., Sutradhar R., Del Giudice L., Urbach D.R. 2011. “Social Disparities in the Use of Colonoscopy by Primary Care Physicians in Ontario.” BMC Gastroenterology 11: 102. 10.1186/1471-230X-11-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain G., Mazhar M.N., Uga A., Punwani M., Broquet K.E. 2012. “Systems-Based Aspects in the Training of IMG or Previously Trained Residents: Comparison of Psychiatry Residency Training in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, India, and Nigeria.” Academic Psychiatry 36(4): 307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K., Baumai B. 2011. “Assessing the Workforce Integration of Internationally Educated Health Professionals.” Retrieved September 12, 2015. <https://www.caot.ca/pdfs/WFI_Report_E.pdf>.

- Keenan M. 2005. “To Ireland and Back.” Canadian Family Physician 51: 1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D., Hofmeister M., Lockyear J., Crutcher R., Fidler H.J. 2009. “Push, Pull and Plant: The Personal Side of Physician Immigration to Alberta, Canada.” International Family Medicine 41(3): 107–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogo S. 2012. Migration of African-Trained Physicians Abroad: A Case Study of Saskatchewan, Canada. Retrieved January 15, 2012. <http://library.usask.ca/theses/available/etd-04282009-120057/unrestricted/SeraphinesThesis2009.finalRSedit.pdf>.

- Landry M.D., Gupta N., Tepper J. 2010. “Internationally Educated Health Professionals and the Challenge of Workforce Distribution.” Healthcare Papers 10(2): 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan A.M., Brailovsky C., Rainsberry P., Bowmer I., Desrochers M. 2010. “Examination Outcomes for International Medical Graduates Pursuing or Completing Family Medicine Residency Training in Quebec.” Canadian Family Physician 56(9): 912–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus B. 2008. “Foreign-Trained Doctors Dominate Pilot Project.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 178(11): 1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masalmeh S. 2009. Integrating International Medical Graduates: Nova Scotia Resources and Gap. Retrieved January 14, 2013. <http://www.isans.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/IMGsNSResourcesGaps2009.pdf>.

- Matejicek A.J. 2009. (Re)Constructing the Meaning of Work: Experiences of Internationally Trained Female Physicians Who Immigrate to Canada. Guelph, ON: University of Guelph. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews M., Edwards A.C., Rourke J.T. 2008. “Retention of Provisionally Licensed International Medical Graduates: A Historical Cohort Study of General and Family Physicians in Newfoundland and Labrador.” Open Medicine 2(2): e62–e69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo E., Mathews M. 2006. “Spousal Perspectives on Factors Influencing Recruitment and Retention of Rural Family Physicians.” Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine 11(4): 271–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J.T., Worswick C. 2010. The Determinants of the Migration Decisions of Immigrant and Non-Immigrant Physicians in Canada. Hamilton, ON: Program for Research on Social and Economic Dimensions of an Aging Population, McMaster University; Retrieved July 5, 2016. <http://socserv.mcmaster.ca/sedap/p/sedap282.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S. 2009. Preliminary Report on Canadian Models for IMG Competency Assessment: Creating a Fair and Equitable Fast Track Assessment Process for International Medical Graduates. Calgary, AB: Alberta International Medical Graduates Association (AIMGA). [Google Scholar]

- Medical Council of Canada (MCC). 2010. Prometric Centres – List of Countries. Retrieved September 12, 2015. <http://mcc.ca/examinations/mccee/list-of-countries-for-prometric-centres/>.

- Medical Council of Canada (MCC). 2013. MCC Annual Report. Accessed January 12, 2013 <www.mcc.ca>.

- Neiterman E., Bourgeault I.L. 2012. “Conceptualizing Professional Diaspora: International Medical Graduates in Canada.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 13(1): 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S., Verma S., Hall L., Gastaldo D., Janjua M. 2011. “The Shifting Landscape of Immigration Policy in Canada: Implications for Health Human Resources.” Healthcare Policy 7(2): 60–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Fairness Commissioner. 2009. Study of Qualifications Assessment Agencies. Ontario, ON: Office of the Fairness Commissioner; Retrieved January 12, 2013. <http://www.fairnesscommissioner.ca/files_docs/content/pdf/en/study_of_qualifications_assessment_agencies_print_pdf_english.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 2013. How to Become a Doctor in Ontario: Information for International Medical Graduates. Retrieved January 23, 2013. <http://www.ontla.on.ca>.

- Peters C. 2013. The Bridging Education and Licensure of International Medical Doctors in Ontario: A Call For Commitment, Consistency, and Transparency. Retrieved January 14, 2013. <http://hdl.handle.net/1807/31896>.

- Physician Recruitment Agency of Saskatchewan. 2012. Physician Recruitment Agency of Saskatchewan: 11-12 Annual Report 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2015. <http://www.saskdocs.ca/web_files/PRAS%20Printed-Tabled%20Annual%20Report%20(July%202011).pdf>.

- Prince Edward Island ANC. 2011. “Microcredit Report – Development of a Microcredit Model for IEHPs Living in Atlantic Canada.” Retrieved June 20, 2013. <http://www.peianc.com/content/lang/en/page/resources_iehpmicrocredit>.

- Sharieff W., Zakus D. 2006. “Resource Utilization and Costs Borne by International Medical Graduates in Their Pursuit for Practice License in Ontario, Canada.” Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 22(2): 110. [Google Scholar]

- Shuchman M. 2008. “Searching for Docs on Foreign Shores.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 178(4): 379–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenerson H.J., Davis P.M., Labash A.M., Procyshyna M. 2009. “Orientation of International Medical Graduates to Canadian Medical Practice.” Journal of Continuing Higher Education 57(1): 29–34. 10.1080/07377360902804051. [Google Scholar]

- Thind A., Feightner J., Stewart M., Thorpe C., Burt A. 2008. “Who Delivers Preventive Care as Recommended? Analysis of Physician and Practice Characteristics.” Canadian Family Physician 54(11): 1574–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thind A., Freeman T., Cohen I., Thorpe C., Burt A., Stewart M. 2007. “Characteristics and Practice Patterns of International Medical Graduates: How Different Are They from Those of Canadian-Trained Physicians?” Canadian Family Physician 53: 1330–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson G., Cohl K. 2011. IMG Selection: Independent Review of Access to Postgraduate Programs by International Medical Graduates in Ontario. Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; Retrieved July 05, 2016. <http://cou.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/COU-Independent-Review-of-IMG-Selection-Volume-I.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Urowitz M.B., Rothman A., Mikhael N. 2008. Physician Assistant Opportunities for International Medical Graduates. International Medical Workforce Collaborative Conference Edinburgh, UK, September 16–20, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vallevand A., Violato C. 2012. “A Predictive and Construct Validity Study of a High-Stakes Objective Clinical Examination for Assessing the Clinical Competence of International Medical Graduates.” Teaching & Learning in Medicine 24(2): 168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violato C., Watt D., Lake D.A. 2011. A Longitudinal Cross-Sequential Study of the Professional Integration of International Medical Graduates (IMGs) from Application to Liscensure. Retrieved June 24, 2013. <http://www.m-cap.ca/pdf/IMGStudyInterimReport_Apr2011.pdf>.

- Walsh A., Banner S., Schabort I., Armson H., Bowmer I., Granata B. 2011. International Medical Graduates – Current Issues. Members of the FMEC PG Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M. 2008. “Analysis of International Migration Patterns Affecting Physician Supply in Canada.” Nursing Leadership 3(3): e129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A., Lohfeld L. 2008. “Recertifying as a Doctor in Canada: International Medical Graduates and the Journey from Entry to Adaptation.” Medical Education 42: 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wildemuth B.M. 2009. “Qualitative Analysis of Content.” In Wildemuth B., ed. Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited. [Google Scholar]