Abstract

Glutamine plus glutamate (Glx), as well as N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc, N-acetylaspartate plus N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate), a marker of neuronal viability, can be quantified with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). We used 1H-MRS imaging to assess Glx and NAAc, as well as total-choline (glycerophospho-choline plus phospho-choline), myo-inositol and total-creatine (creatine plus phosphocreatine) from an axial supraventricular slab of gray matter (GM, medial-frontal and medial-parietal) and white matter (WM, bilateral-frontal and bilateral-parietal) voxels. Schizophrenia subjects (N = 104) and healthy controls (N = 97) with a broad age range (16 to 65) were studied. In schizophrenia, Glx was increased in GM (P < .001) and WM (P = .01), regardless of age. However, with greater age, NAAc increased in GM (P < .001) but decreased in WM (P < .001) in schizophrenia. In patients, total creatine decreased with age in WM (P < .001). Finally, overall cognitive score correlated positively with WM neurometabolites in controls but negatively in the schizophrenia group (NAAc, P < .001; and creatine [only younger], P < .001). We speculate the results support an ongoing process of increased glutamate metabolism in schizophrenia. Later in the illness, disease progression is suggested by increased cortical compaction without neuronal loss (elevated NAAc) and reduced axonal integrity (lower NAAc). Furthermore, this process is associated with fundamentally altered relationships between neurometabolite concentrations and cognitive function in schizophrenia.

Keywords: glutamate, N-acetylaspartate, total-choline, creatine, 1H-MRS, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia is characterized by psychosis and psychosocial deterioration. Cognitive impairment is also common and predicts psychosocial deficits better than psychotic symptoms.1 Understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of cognitive impairment is critical to develop therapeutic strategies that go beyond the resolution of psychosis. It has been postulated that a glutamate-related process accounts for cognitive impairment in schizophrenia.2 The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) hypo-function model of schizophrenia postulates dysfunction of these receptors in gamma-amino-butyric acid interneurons.2 Presumably, this results in disinhibition of pyramidal neurons and a paradoxical increase in presynaptic glutamate release across multiple cortical fields and subsequent dendritic and axonal damage.2

Glutamine plus glutamate (Glx), as well as N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc), a marker of neuronal viability, can be quantified with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM). However, both tissue composition and age have prominent effects on each metabolite’s concentrations.3 Although many studies have measured these metabolites in schizophrenia, samples have been small and brain coverage restricted to a few regions resulting in limited ascertainment of age and tissue composition effects.4–6 For example, GM Glx concentration is about twice as high as in WM.7 In schizophrenia, a disease with subtle but broad GM and WM involvement and progressive structural changes,81H-MRS imaging (1H-MRSI) is potentially a more powerful tool since it enables measurement in a much larger brain region.

In the largest sample of schizophrenia subjects to date, we used a reliable 1H-MRSI9 method at 3 Tesla (T), from a supraventricular tissue slab, to assess Glx and NAAc, as well as total-choline, myo- inositol, and total-creatine from GM and WM voxels. Consistent with the NMDAR hypofunction model we hypothesized: (1) Glx group differences in GM; (2) progressive reduction in WM NAAc as previously described.7 Finally (3) we expected different associations between Glx and cognition in schizophrenia and healthy control groups.7

Methods

Subjects

Schizophrenia patients (SP) were recruited from the University of New Mexico (UNM) Hospitals. Inclusion criteria were: (1) DSM-IV-TR schizophrenia made through consensus by 2 research psychiatrists using the SCID-DSM-IV-TR; (2) if treated, clinically stable on the same antipsychotic medications >4 weeks. Exclusion criteria were diagnosis of neurological or current substance use disorder (except nicotine). Healthy controls (HC) were excluded if they had: (1) any DSM-IV-TR axis-I disorder (SCID-DSM-IV-TR Non-Patient-Version); (2) first-degree relatives with psychotic disorders; (3) history of neurological disorder. The study was approved by the UNM Institutional Review Board. Subjects gave written informed consent.

Magnetic Resonance Studies

Acquisition.

Scanning was performed on a 3 Tesla scanner (VB-17; 12 channel head-coil). T1-weighted anatomical images were obtained with 3D-MPRAGE for voxel tissue segmentation (time to echo/time to repetition/time to inversion [TR/TE/TI] 1500/3.87/700ms, flip angle 10°, field-of-view [FOV] = 256×256mm, 1-mm-thick slice). 1H-MRSI was performed with a phase-encoded version of a point-resolved spectroscopy sequence both with and without water pre-saturation as described.9 The following parameters were used: TE = 40ms, TR = 1500ms, slice thickness = 15mm, FOV = 220×220mm, circular k-space sampling (radius = 12), Cartesian k-space size = 32×32 after zero filling, k-space Hamming filter with 0.5 width and number of averages = 1, total scan time = 582 seconds. A TE of 40ms was chosen to improve detection of the Glx signal.10 The nominal voxel size was 0.71cm3 but the effective voxel volume was 2.4cm3. The 1H-MRSI volume of interest (VOI) was prescribed from an axial T2-weighted image to lie immediately above the lateral ventricles and parallel to the anterior–posterior commissure axis, and included portions of the cingulate gyrus and the medial frontal and parietal lobes (figure 1A). To minimize the chemical shift artifact, the transmitter was set to the frequency of the NAA methyl-peak during the acquisition of the metabolite spectra and to the frequency of the water-peak during the acquisition of the unsuppressed water spectra. Additionally, the outermost rows and columns of the VOI were excluded from analysis.

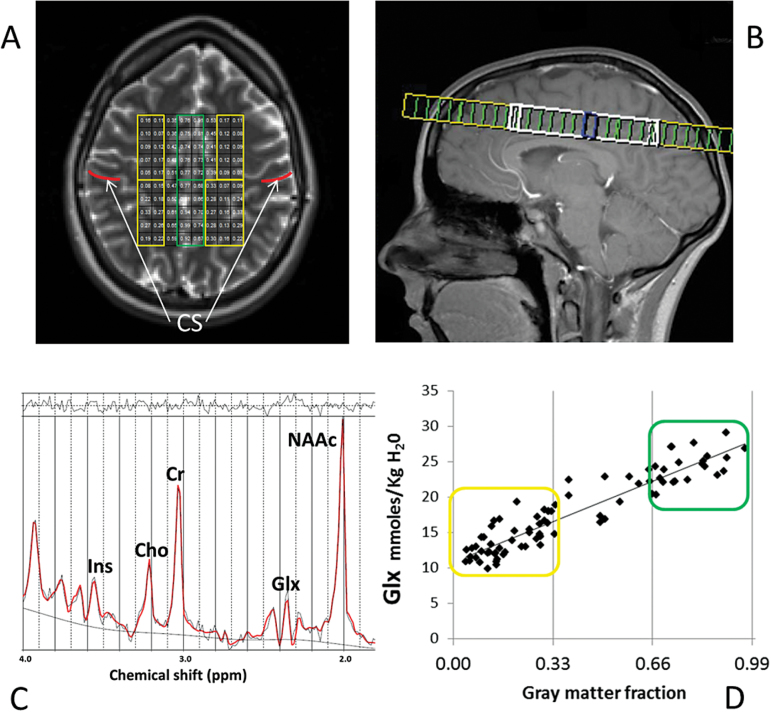

Fig. 1.

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging (1H-MRSI). A: 1H-MRSI supraventricular axial slab with predominantly white matter (WM, yellow) and gray matter (GM, green) voxels. Regions anterior to central sulcus (CS, in red) are frontal. Regions posterior to CS are parietal. B: Sagittal view of A. C: Fitted spectrum (red line) from a predominantly GM voxel. Peak areas for glutamine plus glutamate (Glx), N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc), Cr (total-creatine), Ins (myo-inositol), and Cho (total-choline) are labeled. Top irregular line represents the residual signal. Lower continuous line represents the baseline used for fitting. D: Distribution of Glx values corresponding to the individual voxel’s GM tissue-fraction for the 1H-MRSI from A; in yellow are predominantly WM and in green predominantly GM Glx values.

Spectral Fitting.

Data was automatically preprocessed and fitted using LCModel (Version 6.111). The simulated basis-sets for sequence parameters included the following metabolites: alanine, aspartate, creatine (Cr), phosphocreatine (PCr), gamma-amino-butyric acid, glutamine, glutamate, glycerophosphol-choline (GPC), phospho-choline (PCh), myo-inositol, lactate, N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA), N-acetyl-aspartylglutamate (NAAG), scyllo-inositol and guanidine. The following sums were also reported by the fitting program: Cr+PCr (total-creatine), GPC+PCh (total-choline), NAA+NAAG (NAAc) and Glx. Lipids (2ppm – Lip 20) and macromolecules (2.0ppm – MM20) were simulated using default settings, which include soft constraints for peak position and line width and prior probabilities of the ratios of macromolecule and lipid peaks. Spectra were fitted in the range between 1.8 and 4.2ppm in reference to the non-water-suppressed data using “water-scaling”.9 Only metabolite values with goodness of fit, as measured by the SD, of ≤20% were further analyzed. This resulted in consistently good quality data for Glx, NAAc, total-creatine, total-choline, and myo-inositol for all subjects (figures 1B and 1C).

Partial Volume Correction.

The results from LCModel for the metabolites were corrected for partial volume (using SPM-5 segmented T1 images) and relaxation effects (from literature values), and estimated as concentrations in millimoles per kg of 1H-MRS-visible tissue water (mM).12 There was no need to reposition the 1H-MRSI grid. In order to minimize bias by small errors of cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) segmentation, voxels were classified as “predominantly” gray (100*GM/GM+WM > 66%), “predominantly” white (100*GM/GM+WM < 34%) or mixed (the remaining voxels; figure 1D). Finally, regions-of-interest (ROIs) were selected from “predominantly” GM and WM voxels in each hemisphere, anterior (frontal) and posterior (parietal) to the central sulcus. This resulted in 6 ROI’s: frontal medial GM, left and right frontal WM, parietal medial GM, left and right parietal WM (figure 1A).

Clinical Assessments.

SP and HC completed the Measurement-and-Treatment-Research-to-Improve-Cognition-in-Schizophrenia (MATRICS)13 battery. Patients were assessed for psychopathology with the Positive-and Negative-Syndrome-Scale (PANSS14), the Simpson-Angus-Scale (SAS15) for parkinsonism, the Barnes-Akathisia-Rating-Scale (BARS16) and the Abnormal-Involuntary-Movement-Scale (AIMS17). Inter-rater reliabilities were 0.8 (ICC) for PANSS positive and 0.6 for negative symptoms. Neuropsychological and clinical assessments were completed within 1 week of scan acquisition.

Statistical Analyses.

We implemented PROC-MIXED (SAS version-9) because it uses all available data, accounts for correlation between repeated measurements in the same subject, and can handle missing data more appropriately than other methods.18 The main dependent variables of interest were partial-volume corrected Glx and NAAc. We also examined total-choline, myo-inositol, and total-creatine (Bonferroni-corrected P = .05/3 = .018), other metabolites frequently reported in the schizophrenia literature.4 Because tissue type and age are known variables to affect the metabolites of interest3 and there are progressive tissue changes in schizophrenia,8 the overall approach for each metabolite for all voxels (dependent variable), involved diagnosis as the grouping factor, tissue type (predominantly GM or WM voxels) as the within group factor, and age as a covariate (omnibus test; we also examined if the quadratic effect of age improved the model). If the groups differed in other relevant demographic, substance use or spectral quality measures, these where entered into the model as additional covariates. The potential confound of antipsychotic medication was examined by adding the olanzapine equivalents—OLZ19 to the relevant model in the schizophrenia group.

As suggested,20 the study was powered (80%) to detect a 5% difference in NAAc, with a sample N = 200. To protect against type-1 errors, only the highest order significant interactions or main effects (if no interactions) involving diagnosis are presented in the “Results” and followed-up with PROC-MIXED post hoc tests.21,22 Interactions involving age were followed with a median split of 35 (analyses using age 30 or 40 yielded similar results). Interactions involving tissue type were followed with tests for all the voxels in each of the 2 GM (Bonferroni-corrected, P = .05/2 = .025) and the 4 WM ROIs (P = .05/2 = .0125). Relationships with cognition, positive and negative symptoms, were examined in GM and WM, in younger and older subjects, for the metabolites that differed between SP and HC, also with PROC-MIXED (Bonferroni-correction, 7 tests, P = .05/7 = .007). For all tests, we used Satterthwaite’s correction for unequal variances.

Results

Demographic

One hundred 4 SP and 97 HC participated (table 1 and supplementary table 1). There were no significant differences between the groups in age (P = .66) or familial socioeconomic status (SES; P = .80). The SP had fewer females (Fisher’s P = .02), more smokers (P = .04) and greater histories of cannabis P < .001), stimulant (P < .001), and hallucinogen use disorders (P = .01). The SP group had worse personal SES (t194 = 8.4, P ≤ .001) and lower MATRICS overall t score (t189 = 11.4, P ≤ .001). Finally, all measures of spectral quality as well as GM fraction (GM/GM+WM), differed slightly but significantly between the groups (Ps between .05 and .001; supplementary table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Schizophrenia (n = 104) | Healthy (n = 97) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age (y) | 36.3±13.8 | 37.1±12.3 | .7 |

| Range | 16–64 | 17–65 | |

| Gender (male/female) | 89/15 | 69/28 | .02 |

| SESa | 5.6±1.5 | 3.9±1.3 | .001 |

| Familial SES | 4.4±1.8 | 4.4±1.7 | .8 |

| Vascular risk scoreb | 0.4±0.8 | 0.2±0.5 | .07 |

| MATRICS-overall T | 30.5±13.9 | 50.1±9.5 | .001 |

| Smoker (yes/no) | 34/65 | 20/77 | .04 |

| Alcohol (yes/no) | 30/71 | 19/78 | .1 |

| Cannabis (yes/no) | 36/65 | 6/91 | .001 |

| Stimulant (yes/no) | 13/88 | 0/97 | .001 |

| Opioid (yes/no) | 5/96 | 0/97 | .2 |

| Sedative (yes/no) | 0/101 | 0/97 | 1.0 |

| Cocaine (yes/no) | 5/96 | 1/96 | .2 |

| Hallucinogens (yes/no) | 7/94 | 0/97 | .01 |

| Psychosis onset (y) | 21.1±8.1 | — | — |

| Positive symptoms | 15.8±5.8 | — | — |

| Negative symptoms | 15.8±5.6 | — | — |

| Tardive dyskinesia | 1.6±0.8 | — | — |

| Akathisia | 0.2±0.6 | — | — |

| Parkinsonism | 9.8±2.4 | — | — |

| Antipsychotic (yes/no) | 97/7 | — | — |

| Antipsychotic dose (mg)c | 13.9±11.7 | — | — |

| Antipsychotic 1st/2nd generation | 16/81 | — | — |

| Clozapine (yes/no) | 12/92 | — | — |

| Mood stabilizer (yes/no) | 5/99 | — | — |

| Antidepressant (yes/no) | 28/76 | — | — |

| Antitotal-cholinergic (yes/no) | 17/87 | — | — |

| Benzodiazepine (yes/no) | 21/83 | — | — |

| Beta-blocker (yes/no) | 7/97 | — | — |

Note: MATRICS, Measurement-and-Treatment-Research-to-Improve-Cognition-in-Schizophrenia.

aSocioeconomic status.

bVascular risk score, 0–4 (score of 1 each for cardiac illness, hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes).

cAntipsychotic dose, as olanzapine equivalents.19

Neurometabolite Group Differences

Glutamate ± Glutamine.

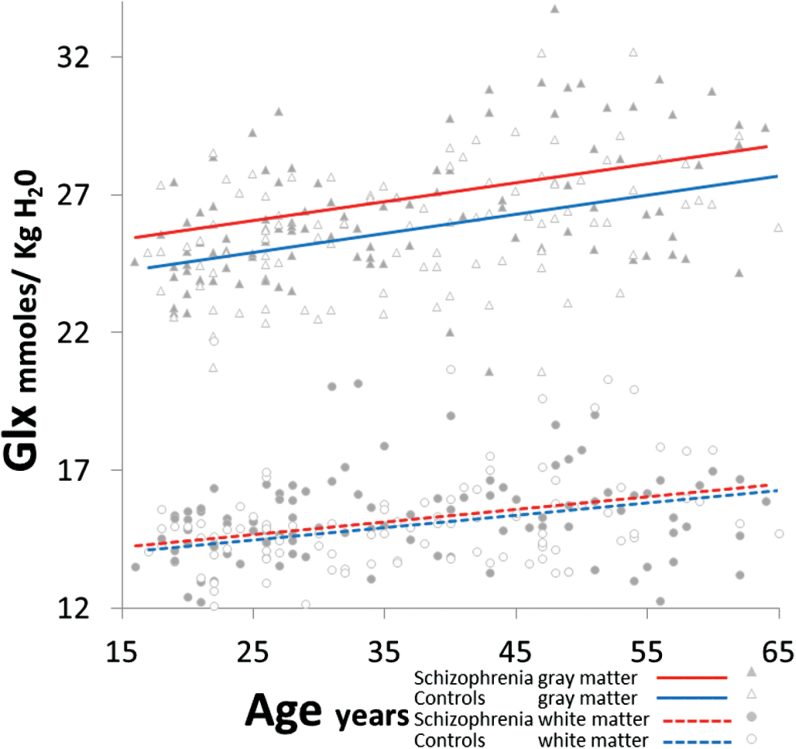

There was a group-by-tissue interaction (F1,197 = 5.3, P = .02; figure 2; see supplementary text for full statistical model), which remained adjusting for smoking-status (P < .001), gender (P = .007), GlxCRLB (P = .005), SNR (P = .01), FWHM (P = .03), GM-fraction (P = .007), cannabis (P = .008), stimulant (P = .009), and hallucinogen abuse (P = .008). There were no group-by-age interactions after adjusting for smoking (P = .5) and gender (P = .8). Also, in SP Glx was not related to OLZ (P = .3). In post hoc PROC-MIXED, Glx was increased in SP vs HC in both GM (F1,197 = 19.5, P < .001) and WM (F1,197 = 5.9, P = .01; see supplementary e-Table 3 for neurometabolite concentrations). For GM, Glx increases in SP vs HC were apparent in medial frontal (F1,197 = 20.3, P < .001) and marginally in medial parietal (F1,196 = 4.0, P = .05) regions. For WM, Glx elevations in SP vs HC were present in the right frontal region (F1,196 = 8.1, P = .005; other Ps = .1–.2).

Fig. 2.

Increased glutamine plus glutamate (Glx) in schizophrenia compared to healthy controls in gray matter (F1,197 = 19.5, P < .001) and white matter (F1,197 = 5.9, P = .01), across age.

NAAc.

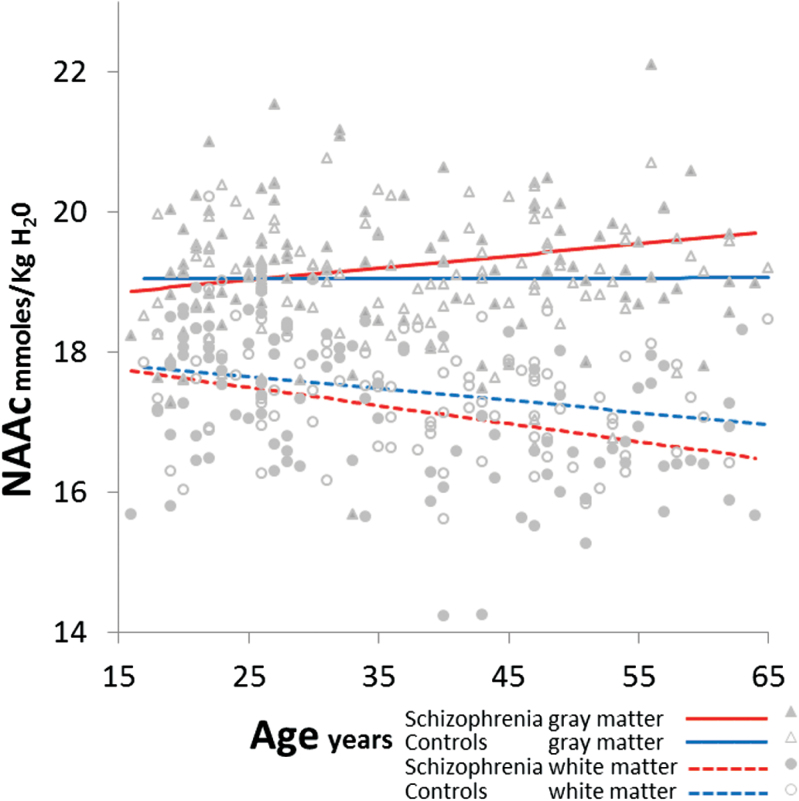

There was a group-by-age-by-tissue interaction (F1,9945 = 21.0, P ≤ .001; figure 3); this remained after controlling for gender (P < .001), smoking (P < .001), NAAcCRLB (P = .007), SNR (P < .001), FWHM (P < .001), GM-fraction (P < .001), cannabis (P < .001), stimulant (P < .001), and hallucinogen abuse (P < .001). Also in SP, the tissue-by-age interaction remained (P < .001) accounting for OLZ. Post hoc PROC-MIXED confirmed that in older SP vs older HC, NAAc was increased in GM (F1,101 = 14.3, P < .001) but reduced in WM (F1,101 = 62.2, P < .001; supplementary table 2). In younger SP vs younger HC NAAc was also reduced in WM (F1,96 = 12.1, P < .001), but not in GM (F1,96 = 0.0, P = .99). Amongst the older subjects, NAAc was increased in medial frontal GM in SP vs HC (F1,101 = 8.8, P = .004). In WM, NAAc was reduced in older SP vs older HC in all 4 regions: frontal left (F1,101 = 28.2, P < .001) and right (F1,101 = 13.1, P < .001) and parietal left (F1,101 = 13.2, P < .001) and right (F1,101 = 14.8, P < .001). However, in the younger SP vs younger HC, NAAc was reduced in only one WM region: right frontal (F1,96 = 21.9, P < .001; other Ps = .09–.7).

Fig. 3.

Increased N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc) in gray matter (GM, F1,101 = 14.3, P < .001) but reduced in white matter (WM, F1,101 = 62.2, P < .001) in older (≥35 y) schizophrenia compared with healthy controls. In younger schizophrenia subjects WM NAAc is also decreased (F1,96 = 12.1, P < .001).

Other Metabolites.

For total-creatine there was a group-by-age2-by-tissue interaction (the quadratic [F1,9897 = 32.2, P < .001] but not the linear effect of age [P = .1], was significant). This interaction remained after controlling for gender, smoking, cannabis, stimulant, hallucinogen, total-creatineCRLB, SNR, FWHM and GM-fraction (all Ps < .001). Also in SP, the tissue-by-age2 interaction remained (P < .001) accounting for OLZ. In post hoc PROC-MIXED amongst older subjects, total-creatine was reduced in SP vs HC only in WM (F1,101 = 11.2, P = .001). These reductions were apparent only in right parietal WM (F1,101 = 13.7, P < .001; other Ps = .1–.8). For myo-inositol and total-choline there were no interactions or main effects involving group (Ps = .06–.6; see supplementary text). Also, for Glx, NAAc and total-creatine, analyses with duration of illness in the SP group failed to detect effects independent of age (age and duration of illness were highly correlated, r102 = .89, P < .001). Finally, results did not change in analyses with GM tissue-fraction as continuous and age as dichotomous variables.

Cognitive/ Clinical and Metabolite Relationships

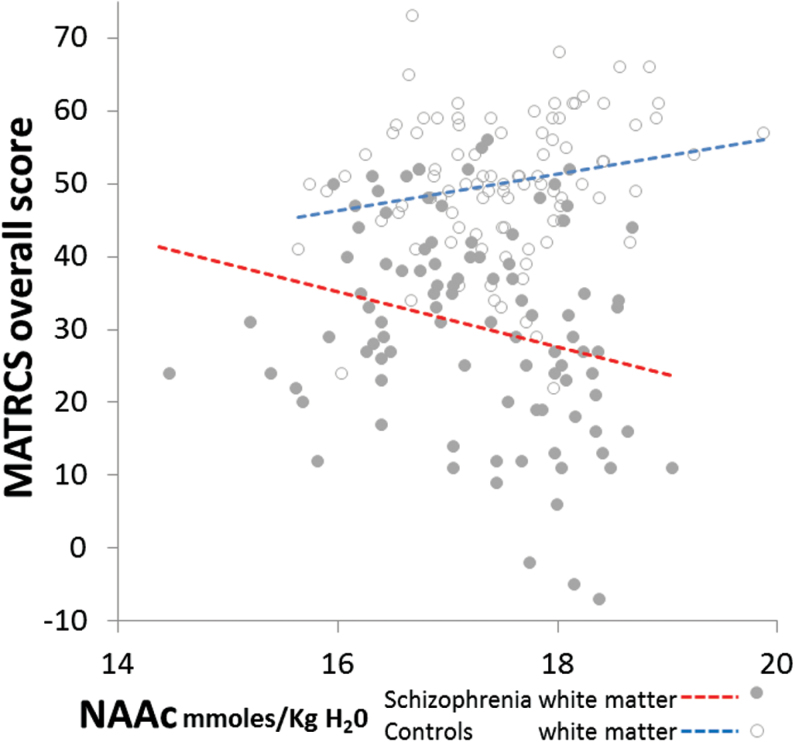

Because of the complex relationships between group, age and tissue, we examined whether neurochemicals affected in SP related to cognition and symptoms in 4 subject subgroups: younger and older, in GM and WM each (corrected P = .007). For MATRICS-overall t-score, the subgroups had different correlations with 2 metabolites (positive in HC and negative in SP), only in WM regions. For NAAc: in younger (F1,283 = 14.1, P < .001), and in older (F1,286 = 13.5, P < .001; figure 4); and for total-creatine, in younger subjects (F1,283 = 19.8, P < .001). These 3 interactions remained after adjusting for smoking-status, gender, NAACCRLB, total-creatineCRLB, SNR, FWHM, GM-fraction, cannabis, stimulant, and hallucinogen abuse (all Ps < .001). Although suggestive in WM, the hypothesized group differences in MATRICS vs Glx relationships did not survive Bonferroni corrections: F1,283 = 3.8, P = .05 in younger and F1,280 = 3.9, P = .05 in older subjects.

Fig. 4.

Opposite relationship between white matter N-acetylaspartate compounds (NAAc) (age-adjusted) and Measurement-and-Treatment-Research-to-Improve-Cognition-in-Schizophrenia (MATRICS) overall score in schizophrenia and healthy controls (F1,571 = 27.9, P < .001).

Positive symptoms were positively correlated with WM Glx in older SP (F1,134 = 8.0, P = .005) and negatively correlated with WM NAAc in older SP (F1,140 = 9.4, P = .003). These correlations remained after adjusting for OLZ, smoking-status, gender, NAACCRLB, GlxCRLB, FWHM, GM-fraction, cannabis, stimulant, and hallucinogen abuse (Ps = .04 to <.001), but not after controlling for SNR (P = .3 and .08 for WM NAAc and Glx, respectively). Negative symptoms were not related to the metabolites (Ps = .1–1.0), but were negatively related with MATRICS-score (r96 = −.42, P < .001). Positive symptoms were not related to MATRICS-score (P = .3).

Discussion

In the largest 1H-MRS study of schizophrenia to date, we find increased levels of GM Glx in medial frontal and marginally in medial parietal cortex. Glx was also elevated in right frontal WM. However, NAAc varied with age in schizophrenia in more complex ways: higher in frontal GM but lower in WM (in all 4 regions), in older subjects. Also total-creatine was lower in older SP in right-sided parietal WM. Myo-inositol and total-choline did not differ between the groups. For NAAc and total-creatine (only in WM), the relationships with overall cognition were fundamentally different between the groups: negative in SP and positive in HC. Finally, among older SP, positive symptoms were negatively correlated with WM NAAc but positively correlated with WM Glx.

The 1H-MRS schizophrenia literature has been summarized in 3 meta-analyses: 1 focused on glutamate and glutamine6 and 2 on NAAc and other metabolites.4,5 When discussing this literature, 1H-MRS methods (eg, spectral quality), brain region examined and state vs trait issues must be considered. The glutamate meta-analysis reported increased glutamine and reduced glutamate, in medial frontal single-voxel studies,6 with progressive reductions with age. These results did not appear related to a more ventral23–25 or dorsal frontal placement.26–30 However, the quality of the spectral fits is not always clear in these reports (except for27–29) and the samples were small (9 to 30 for the schizophrenia groups6). More recent studies reported increases,31–35 reductions25,36–38 and no differences39 in Glx or glutamate. Two33,34 of the 5 recent studies documenting elevations involved more ventral regions. Of particular interest are studies in unmedicated patients which consistently report higher Glx (in striatum,34 hippocampal33 and medial frontal regions35) and normalization with antipsychotic treatment. We previously reported increased glutamine but normal glutamate in the dorsal anterior cingulate.40 We included 72 medicated SP and 76 HC whom also participated in the present study. Since glutamine involves about one-third to one-fifth of the Glx signal41 we speculate that our current results of increased Glx may represent primarily elevations in glutamine. Also, our present findings document a much smaller increase in Glx (2.6% in GM and 1.4% in WM) than most previous studies. For example, in the striatum of antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia, a 10% increase in Glx was reported.34 Following a 4-week treatment the elevation was only 6% (not statistically significant, with N = 40). The short-term longitudinal studies33,34 strongly support that antipsychotic treatment has a normalizing (reducing) effect on Glx. However, our findings support that at least in more dorsal medial frontal cortex, a small increase in Glx persists, despite antipsychotic treatment, suggesting a trait effect.

Many schizophrenia studies have examined NAAc mostly in large single-voxels with mixtures of GM and WM. The meta-analyses4,5 are generally consistent in supporting NAAc reductions in the hippocampus, thalamus, frontal and temporal lobe, with no apparent differences between GM and WM nor differences related to stage of illness. However, these analyses did not consider criteria for quality of spectral fits nor partial-volume tissue correction, factors known to affect metabolite values.42 In addition to the unaddressed methodological heterogeneity, only 8 of the 103 studies were powered to detect a 10% difference in NAAc (with SP, N ≥ 39).4,5 Furthermore, there were only 8 1H-MRSI studies, and only 2 with SP samples ≥39,4 both of which focused only on one structure: the thalamus43 and the hippocampus.44 Hence the likelihood of detecting subtle cortical GM vs WM tissue differences in the current literature is slim. We detected a 2% WM NAAc reduction and a 1.3% GM increment, but only in older (>35 y) SP. In addition, we found that WM reduction (1%) is apparent early in the illness (these NAAc differences represent small effect sizes, supplementary table 2). Our results converge with the first 1H-MRSI study45: in supraventricular WM, NAAc was reduced (9%) among SP (age range 34–54); GM NAAc was increased (3.8%), though not significantly (N = 19).

The meta-analysis that examined total-choline and total-creatine in frontal, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and thalamus found no group differences.4 In our study of the dorsal anterior cingulate, we did find higher total-choline in SP but no differences in total-creatine.40 Again, the current study is by far the largest to examine these 2 neurometabolites in schizophrenia.

What is the biological meaning of these admittedly small group differences? A glutamatergic-mediated excitotoxic process has been postulated in schizophrenia2 and 6 genes involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission were identified in the largest genetic study (however, the 108 total loci identified only accounted for 3.4% of diagnostic variance, highlighting the frustratingly small biological effects often seen in schizophrenia46). Early in the illness we find an increase in Glx in GM and WM, consistent with greater glutamatergic turnover.47 Later in the illness this process remains, but additional differential tissue-specific changes occur: in GM, higher NAAc suggestive of neuronal compaction47; in WM, reduced NAAc and total-creatine, suggestive of axonal dysfunction and altered energy metabolism, respectively. Longitudinal GM (0.6%/y) and WM (0.3%/y) volume reductions (which decrease with age) have been documented in schizophrenia8 as well as in un-affected twins,48 suggestive of disease progression. However, there is no widespread neuronal loss or gliosis49 suggestive of classic neuro-degeneration. Still, cortical neuropil reductions (23% but only in deep layer III50) and increased neuronal density (17% in layers III–VI51), have been found. Furthermore, glutamatergic excitotoxicity can selectively retract dendritic spines in animal models52 and sub-chronic NMDA blockade leads to spine reduction as well as an increase in astroglial processes.53 Axonal dysfunction could be a consequence of the cortical glutamatergic process. However, increased Glx in right frontal WM early in the illness could directly affect axons and result in NAAc reductions.47 Overall, our findings are consistent with an NMDAR hypofunction process of glutamatergic sub-lethal excitotoxicity in GM and WM, which progresses but without neuronal loss. Effective antipsychotic treatment probably reduces glutamatergic turnover but not enough to completely arrest the underlying process.

In terms of potential clinical significance, the disrupted neurometabolic pattern is associated with broad cognitive impairment, a core deficit in schizophrenia. The normal positive relationships between NAAc and total-creatine (in WM), and cognition are inverted. The fact that these relationships are present early in the illness, regardless of whether the neurometabolite is decreased (WM NAAc) or unchanged (WM total-creatine), suggest that tissue adaptations underlying cognition precede the evolving excitotoxic process. In a subsample of 64 SP and 64 HC included in these analyses, we reported that despite reductions in fractional anisotropy (FA), the schizophrenia group had a negative correlation between FA and MATRICS-score, while the HC had a positive relationship.54 Hence, the microstructural organization of WM in schizophrenia appears to support cognition in a fundamentally different way. The relationships with psychosis are not consistent with our previous report of a direct correlation between dorsal cingulate glutamine and positive symptoms.40 Hence findings with respect to correlations of neurometabolites with positive symptoms need replication.

This study has several strengths. 1H-MRSI allowed examination of supraventricular GM and WM regions known to be involved in schizophrenia.55 The large sample included a broad age range. Voxel tissue-composition and age are known to have large effects on the concentrations of 1H-MRS neurometabolites. By accounting for these factors we detected subtle differences between groups, but also in relationships with cognition. However, limitations must be acknowledged. First, spectral resolution did not allow separation of glutamine from glutamate or NAA from NAAG. It may be that NAAG increases in GM latter in the illness to down-regulate a higher turnover of glutamate in these subjects,56 resulting in elevated NAAc. Also Glx levels do not measure the rate of glutamatergic metabolism. Second, brain coverage was limited to supraventricular tissue excluding outer cortical and ventral GM. Although not systematically evaluated, other studies with smaller samples have failed to detect abnormalities in dorsal regions.7,35,57–59 Also, several studies suggest that glutamatergic increases may be more robust in ventral brain regions23,24,33–35,60–62 with effect sizes larger than here reported. We are currently implementing a whole-brain 1H-MRSI sequence.63 Third, the SPs received antipsychotic medication. Though covariance with antipsychotic dosage did not change the findings, antipsychotics can reduce hippocampal33 and striatal34 glutamate. Hence, the small elevations we report may be moderated by treatment. Fourth, a minority of SP also were taking other psychotropics. Though the available literature is generally mixed, some studies reported that lithium may increase NAAc, valproate may decrease Glx and antidepressants may reduce total-choline (reviewed in64). Fifth, smoking and prior illegal substance use were more frequent among SP and could contribute to increased Glx; however, co-variation of these measures did not change the results. Six, we did not measure water T2 so age-by-group effects could be confounded by errors in water quantification. Seventh, a shorter TE acquisition may have been more sensitive to potential myo-inositol group differences. Finally, this was a cross-sectional study, so mechanistic interpretations are inherently limited.

In summary 1H-MRSI spectra from a large cohort of SP and HC revealed subtle neurometabolic abnormalities superimposed on larger tissue and age-related effects. During the course of the illness, GM and WM abnormalities are consistent with greater glutamatergic turnover. Later in the illness, additional differential tissue-related changes take place, consistent with neuronal compaction in GM and axonal dysfunction in WM. These findings supplement the large morphometric literature in schizophrenia that documents neuro-progressive changes.8 Longitudinal studies examining whole brain 1H-MRSI early in the illness will further clarify the mechanism by which increased glutamatergic metabolism contributes to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. This line of translational investigation may identify subgroups of patients, for whom drugs, such as metabotropic MGluR2-3 agonists65 may be particularly helpful to prevent cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Supported by NIMH R01MH084898 to J. R. Bustillo and 1 P20 RR021938-01A1 and DHHS/NIH/NCRR 3 UL1 RR031977-02S2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

J.R.B. has received honoraria for non-promotional talks from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals North America Inc.

References

- 1. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olney JW, Farber NB. Glutamate receptor dysfunction and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maudsley AA, Domenig C, Govind V, et al. Mapping of brain metabolite distributions by volumetric proton MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:548–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kraguljac NV, Reid M, White D, et al. Neurometabolites in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;203:111–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steen RG, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA. Measurement of brain metabolites by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1949–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of ¹H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:120–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bustillo JR, Chen H, Gasparovic C, et al. Glutamate as a marker of cognitive function in schizophrenia: a proton spectroscopic imaging study at 4 Tesla. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olabi B, Ellison-Wright I, McIntosh AM, Wood SJ, Bullmore E, Lawrie SM. Are there progressive brain changes in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis of structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gasparovic C, Bedrick EJ, Mayer AR, et al. Test-retest reliability and reproducibility of short-echo-time spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mullins PG, Chen H, Xu J, Caprihan A, Gasparovic C. Comparative reliability of proton spectroscopy techniques designed to improve detection of J-coupled metabolites. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:964–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gasparovic C, Song T, Devier D, et al. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buchanan RW, Davis M, Goff D, et al. A summary of the FDA-NIMH-MATRICS workshop on clinical trial design for neurocognitive drugs for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:5–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schooler NR, Kane JM. Research diagnoses for tardive dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:486–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch General Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:686–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Venkatraman TN, Hamer RM, Perkins DO, Song AW, Lieberman JA, Steen RG. Single-voxel 1H PRESS at 4.0 T: precision and variability of measurements in anterior cingulate and hippocampus. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Day BA. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research Volume I - The Analysis of Case-control Studies. Lyon, France:IARC Publications; 1980:196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koopman L. An Introduction to Contemporary Statistics. Kent, England: PWS Kent Publishers; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartha R, Williamson PC, Drost DJ, et al. Measurement of glutamate and glutamine in the medial prefrontal cortex of never-treated schizophrenic patients and healthy controls by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Theberge J, Bartha R, Drost DJ, et al. Glutamate and glutamine measured with 4.0 T proton MRS in never-treated patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1944–1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lutkenhoff ES, van Erp TG, Thomas MA, et al. Proton MRS in twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:308–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bustillo JR, Rowland LM, Mullins P, et al. 1H-MRS at 4 tesla in minimally treated early schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ongur D, Jensen JE, Prescot AP, et al. Abnormal glutamatergic neurotransmission and neuronal-glial interactions in acute mania. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shirayama Y, Obata T, Matsuzawa D, et al. Specific metabolites in the medial prefrontal cortex are associated with the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2783–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stone JM, Day F, Tsagaraki H, et al. Glutamate dysfunction in people with prodromal symptoms of psychosis: relationship to gray matter volume. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tayoshi S, Sumitani S, Taniguchi K, et al. Metabolite changes and gender differences in schizophrenia using 3-Tesla proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Schizophr Res. 2009;108:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ota M, Ishikawa M, Sato N, et al. Glutamatergic changes in the cerebral white matter associated with schizophrenic exacerbation. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Egerton A, Brugger S, Raffin M, et al. Anterior cingulate glutamate levels related to clinical status following treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2515–2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kraguljac NV, White DM, Reid MA, Lahti AC. Increased hippocampal glutamate and volumetric deficits in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1294–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Leon-Ortiz P, Azcarraga M, et al. Glutamate levels in the associative striatum before and after 4 weeks of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1057–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kegeles LS, Mao X, Stanford AD, et al. Elevated prefrontal cortex gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate-glutamine levels in schizophrenia measured in vivo with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stan AD, Ghose S, Zhao C, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and tissue protein concentrations together suggest lower glutamate signaling in dentate gyrus in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Natsubori T, Inoue H, Abe O, et al. Reduced frontal glutamate + glutamine and N-acetylaspartate levels in patients with chronic schizophrenia but not in those at clinical high risk for psychosis or with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1128–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rowland LM, Summerfelt A, Wijtenburg SA, et al. Frontal glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels and their associations with mismatch negativity and digit sequencing task performance in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:166–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kraguljac NV, Reid MA, White DM, den Hollander J, Lahti AC. Regional decoupling of N-acetyl-aspartate and glutamate in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2635–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bustillo JR, Chen H, Jones T, et al. Increased glutamine in patients undergoing long-term treatment for schizophrenia: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 3 T. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Govindaraju V, Young K, Maudsley AA. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13:129–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kreis R. Issues of spectral quality in clinical 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy and a gallery of artifacts. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:361–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martinez-Granados B, Brotons O, Martinez-Bisbal MC, et al. Spectroscopic metabolomic abnormalities in the thalamus related to auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;104:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Callicott JH, Egan MF, Bertolino A, et al. Hippocampal N-acetyl aspartate in unaffected siblings of patients with schizophrenia: a possible intermediate neurobiological phenotype. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Spielman D, Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of cortical gray and white matter in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rae CD. A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brans RG, van Haren NE, van Baal GC, Schnack HG, Kahn RS, Hulshoff Pol HE. Heritability of changes in brain volume over time in twin pairs discordant for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1259–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Harrison PJ. The neuropathology of schizophrenia. A critical review of the data and their interpretation. Brain. 1999;122:593–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glantz LA, Lewis DA. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Selemon LD, Rajkowska G, Goldman-Rakic PS. Abnormally high neuronal density in the schizophrenic cortex. A morphometric analysis of prefrontal area 9 and occipital area 17. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:805–818; discussion 19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McEwen BS, Magarinos AM. Stress effects on morphology and function of the hippocampus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;821:271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hajszan T, Leranth C, Roth RH. Subchronic phencyclidine treatment decreases the number of dendritic spine synapses in the rat prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Caprihan A, Jones T, Chen H, et al. The paradoxical relationship between white matter, psychopathology and cognition in schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor and proton spectroscopic imaging study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2248–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PC, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1129–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Neale JH, Olszewski RT, Zuo D, et al. Advances in understanding the peptide neurotransmitter NAAG and appearance of a new member of the NAAG neuropeptide family. J Neurochem. 2011;118:490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stanley JA, Williamson PC, Drost DJ, et al. An in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ohrmann P, Siegmund A, Suslow T, et al. Evidence for glutamatergic neuronal dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex in chronic but not in first-episode patients with schizophrenia: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Schizophr Res. 2005;73:153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bernier D, Cookey J, McAllindon D, et al. Multimodal neuroimaging of frontal white matter microstructure in early phase schizophrenia: the impact of early adolescent cannabis use. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Theberge J, Williamson KE, Aoyama N, et al. Longitudinal grey-matter and glutamatergic losses in first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. de la Fuente-Sandoval C, Leon-Ortiz P, Favila R, et al. Higher levels of glutamate in the associative-striatum of subjects with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia and patients with first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1781–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Aoyama N, Theberge J, Drost DJ, et al. Grey matter and social functioning correlates of glutamatergic metabolite loss in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Verma G, Woo JH, Chawla S, et al. Whole-brain analysis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by using echo-planar spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2013;267:851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bustillo JR. Use of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: a critical update. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patil ST, Zhang L, Martenyi F, et al. Activation of mGlu2/3 receptors as a new approach to treat schizophrenia: a randomized Phase 2 clinical trial. Nat Med. 2007;13:1102–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.