Abstract

We investigated relative clause (RC) comprehension in 44 Russian-speaking children with typical language (TD) and developmental language disorder (DLD); M age = 10.67, SD = 2.84, and 22 adults. Flexible word order and morphological case in Russian allowed us to isolate factors that are obscured in English, helping us to identify sources of syntactic complexity and evaluate their roles in RC comprehension by children with typical language and their peers with DLD. We administered a working memory and an RC comprehension (picture-choice) task, which contained subject- and object-gap center-embedded and right branching RCs. The TD group, but not adults, demonstrated the effects of gap, embedding, and case. Their lower accuracy relative to adults was not fully attributable to differences in working memory. The DLD group displayed lower than TD children overall accuracy, accounted for by their lower working memory scores. While the effect of gap and embedding on their performance was not different from what was found for the TD group, children with DLD exhibited a diminished effect of case, suggesting reduced sensitivity to morphological case markers as processing cues. The implications of these results to theories of syntactic complexity and core deficits in DLD are discussed.

Keywords: developmental language disorder, syntactic complexity, working memory, relative clause, sentence comprehension

1. Introduction

This study investigated comprehension of sentences with Relatives Clauses (RC) by Russian-speaking children with and without Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). We will use the term DLD to refer to the clinical condition commonly referred to as Specific Language Impairment (SLI)1, i.e., persistent difficulties in the acquisition and use of language not attributable to sensory impairment, motor dysfunction, or another medical or neurological condition and not better explained by intellectual disability or global developmental delay (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). By examining patterns of accuracy in comprehension of various types of RCs by typically developing children, children with DLD and healthy Russian-speaking adults, we sought evidence for (or against) those theoretical accounts of syntactic complexity that attribute differential amount of cognitive effort required for processing different types of RCs to working memory demands as opposed to other, non-resource capacity related factors. Secondly, we asked whether the core deficits underlying sentence comprehension difficulties in children with DLD are best understood as missing/incomplete syntactic knowledge (the view we will refer to as the syntactic deficit view), consequences of reduced working memory capacity (processing deficit view), and/or the facility with deploying morphological knowledge during sentence comprehension (morphological deficit view).

The juxtaposition between the syntactic, processing, and morphological views of DLD mirrors the debate about the factors underlying syntactic-complexity-related phenomena, i.e., the fact that certain types of sentences and regions within a given sentence educe differential degrees of difficulty for comprehension. In the remainder of the paper, we will review the main views on the role of working memory capacity in syntactic complexity, present major approaches to syntactic complexity of RCs, briefly discuss major approaches to language deficits in DLD, give a brief overview of typical RC acquisition research, and present an experimental study of RC comprehension by Russian-speaking children with DLD, their TD age peers, and healthy adults. We will argue that according to our findings, working memory capacity must be at least part of the theory of syntactic complexity. Secondly, we will argue that our results support the multifactorial view of DLD, as a disorder characterized by both limitations in working memory and a deficit directly traceable to using morphological markers during sentence comprehension. Thus, we will maintain that to account for the wide range of effects in acquisition and processing of RCs, theoretical accounts need not choose between working memory capacity and the facility in using grammatical knowledge, but should appeal to both.

1.1 Working Memory and Syntactic Complexity

The role of working memory in sentence processing has long been recognized. Classic work by Baddeley and Hitch (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974) revealed that language comprehension and simultaneous digit recall draw on shared resources. A widely cited theory built on this discovery (Just & Carpenter, 1992)2 construed working memory as a system supporting both storage and processing by providing finite amount of available activation. As each representational unit (from morphemes to syntactic and semantic structures, propositions and discourse entities) becomes activated during sentence comprehension, and, as computations are performed on these elements altering their activation levels, the amount of available activation may become insufficient, rendering old elements deactivated. This theory implies that individual differences in working memory are directly related to the level of accuracy with which individuals process complex syntactic structures (e.g., center embedded object-gap RCs). Various mechanisms relating working memory capacity and grammatical computation have been proposed by demonstrating effects of syntactic complexity on the performance of adults and children within the normal range of language processing capacity and with acquired and developmental language disorders (King & Just, 1991; MacDonald, Just, & Carpenter, 1992). One approach examined the effects of similarity-based interference on working memory, a constraint on information processing posited by Gordon, Hendrick, & Jonson (2001). In their study, Gordon and colleagues found that comprehension of cleft sentences was significantly hampered if the critical NPs in the sentence were of the same semantic type (both were either names or descriptions). They also found that this similarity-based interference effect was greater for more syntactically complex Object-gap sentences (relative to the easier Subject-gap).

Even though the idea that the efficiency with which we deploy linguistic knowledge during sentence comprehension is constrained by our working memory capacity has been widely accepted, it has also been disputed. It has been argued that working memory, typically measured by sentence span tasks, is not the system deployed during “interpretive processing” (Caplan & Waters, 1998), i.e., operations performed to extract meaning from the linguistic signal (recognizing words, retrieving their meanings and syntactic features, constructing syntactic and semantic representations, computing information structure and other aspects of propositional and discourse-level semantics). In contrast, “post-interpretive” processing (storing semantic information to be used for reasoning, planning, etc.), engages working memory. This view calls for alternative explanations of syntactic complexity.

Mutiple explanations of syntactic complexity effects unrelated to memory capacity have indeed been proposed, including 1) non-canonical word order requiring one to rely on grammatical markers rather than a general interpretive heuristic when assigning thematic roles to arguments (Caplan & Waters, 1999); 2) greater representational complexity (Lin & Bever, 2006; O’Grady, 1997) or 3) lower frequency (MacDonald & Christiansen, 2002) of certain structural configurations; 4) violation of expectations during parsing (Levy, 2008; Levy & Smith, 2013); 5) perspective shift (MacWhinney & Pléh, 1998); and 6) structural constraints on syntactic representation of phrasal movement (the Relativized Minimality account; Adani, van der Lely, Forgiarini, & Guasti, 2010).

The role played by memory capacity limitations in syntactic processing is a fundamental question in both psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics and is essential to our understanding of normal language acquisition and the nature of linguistic deficits in children with Developmental Language Disorders.

1.2 Relative Clauses as a Probe into Language Processing Capacity

RCs have been recognized as an important probe into sentence processing and language acquisition because their grammatical properties allow the notion of syntactic complexity to be precisely defined. Although the structure of RC sentences allows cross-linguistic variation, the basic type of RC sentences used in the majority of studies contains a noun phrase, i.e., the relativized RC head, modified by a subordinate clause restricting its reference. The syntactic position of the RC head may vary, e.g., the subject of the matrix verb (as in 1 and 2) with the RC interrupting the matrix clause (henceforward, center-embedded or CE), or the object of the matrix verb (as in 3 and 4), with the RC embedded at the right periphery of the matrix clause (henceforward, right-branching or RB).

A key element of the RC structure that makes it an interesting tool for studying human capacity for sentence processing is that it contains a gap, i.e., the position where a thematic role is assigned by the RC verb to a phonologically empty constituent (e in the examples below) co-referring with the RC head (indicated by co-indexation), joined with the matrix clause by a pronominal (as the English “who/whom”) or non-pronominal (as the English “that”) relativizer. The syntactic position of the gap may vary, e.g., the subject, as in (1) and (3) or direct object, as in (2) and (4) of the RC, hence the terms subject-gap and object-gap RCs.

| (1) | The authori that [ei interviewed the journalist] won the Pulitzer Prize. |

| (2) | The authori that [the journalist interviewed ei] won the Pulitzer Prize. |

| (3) | The author interviewed the journalisti that [ei won the Pulitzer Prize.] |

| (4) | The Pulitzer Prize was given to the journalisti that [the author interviewed ei.] |

The complex relationship between the RC head, the relative pronoun and the gap has been conceptualized as syntactic movement (or feature-passing), e.g., positing an underlying structure in which the relativized constituent is generated in an argument position within the RC (e.g., as the internal or external argument of the RC verb), moves to the left edge of the RC, the surface position of the relativizer, from where the NP is raised to its surface position in the matrix clause (Bianchi, 2002).

Thus, a defining property of RCs is that they contain a syntactically and semantically complex constituent, called the pivot, shared by the matrix and the relative clause (Alexiadou, Law, Meinunger, & Wilder, 2000; de Vries, 2002). A source of semantic complexity of RCs is that the pivot plays a double role by being interpreted separately in the relative and the matrix clause. Thus, in (1) the pivot (“author”) is understood as both the agent of the matrix verb (“won”) and the RC verb (“interviewed”). In examples like (2), the pivot is understood as the agent of the matrix verb, but also as the theme of the RC verb.

To interpret an RC sentence, one has to build a complex syntactic structure containing a potentially recursive subordinate clause, identify the syntactic position and thematic role of the gap, establish its reference by linking it to the RC head, and complete the interpretation of the matrix clause. This involves both sophisticated representational knowledge and extensive processing resources making RCs a sensitive tool for identifying areas of vulnerability in both a normal and disordered linguistic system.

1.3 Approaches to Relative Clause Complexity

Much of the RC literature focuses on identifying the key factors underlying variable difficulty of various RC types to understand the nature of the human language processor and the constraints under which it operates. Among the most widely discussed determinants of RC complexity are the syntactic position of the RC head, the congruency of the theta-roles of the RC head and RC gap, and the syntactic position of the gap.

With respect to the syntactic position of the RC head, the contrast between CE and RB structures involving multiple embeddings is well attested (Gibson, 1998; King & Just, 1991; Miller & Chomsky, 1963), although there are inconsistent findings with respect to the effect of single embeddings (MacWhinney & Pleh, 1988). The higher processing complexity of center-embedded (CE) RCs relative to right-branching (RB) RCs was argued to be due to their greater working memory demands, i.e., requiring one to retain a representation of the RC head in working memory, while processing the interrupting RC clause, before merging the RC head with the matrix verb (Gibson, 1998; King & Just, 1991).

Another complexity factor thought to be related to differential working memory demands was a parallelism between the thematic roles of the head and that of the gap, with a higher complexity observed in those RCs in which the two are not parallel. Thus CE (subject modifying) RCs with object-gap and RB (object modifying) RCs with subject-gap were shown to have higher complexity than the other types (King & Just, 1991; Sheldon). This was attributed to greater processing demands imposed by sentences with non-parallel functions. In languages with overt Case marking, this effect was suggested to be related to Case morphology. Thus, according to the Case Matching hypothesis (Sauerland & Gibson,1998), RCs in which the case of the extracted element does not match the head noun of the RC are associated with greater complexity.3

The most widely discussed issue in RC literature is the asymmetry in processing complexity of subject- versus object-gap RCs. The explanations of this asymmetry are very diverse (for a recent comprehensive review of theories of RC complexity see Levi, Fedorenko, Gibson, 2013; Gibson, Tily, & Fedorenko, 2014).

A common explanation of this phenomenon is that the filler-gap dependency in subject-gap RCs is shorter than in object-gap ones (in head-initial languages). Various mechanisms for implementing the valuation of the filler-gap distance and for how this length affects RC processing have been proposed. One influential approach connects the length of the filler-gap dependency with working memory demands for storage and integration of linguistic material (Gibson, 1998, 2000; Just & Carpenter, 1992). The length is measured by the number of elements (e.g., full NPs) intervening between the filler and the gap (Babyonyshev & Gibson, 1999; Gibson, 1998, 2000). This correctly captures the contrast in the linear distance between subject- and object-gap RCs in English, as in the former there are no intervening NPs, while in the latter, the subject NP intervenes. This contrast can be eliminated in languages with a flexible word order, such as Russian, thus predicting no subject-object-gap asymmetry with respect to storage and integrations costs for sentences without an intervening argument.

An alternative, unrelated to resource capacity, approach treats the greater complexity of object-gap RCs as a consequence of a violation of expectations. Under this approach, it is stipulated that the parser posits shorter dependencies by default but upon encountering cues signaling a need for re-analysis abandons them (Frazier & Clifton, 1989). Thus, the default interpretation is subject-gap, while the object-gap interpretation involves reanalysis. This approach works well for English, where, in the absence of case marking, RC sentences contain a temporary structural ambiguity; i.e. the string “the author who” is compatible with both subject- and object-gap reading. In languages with overt case marking, RCs may be disambiguated at their onset by the case of the relativizer, and, therefore, object-gap interpretation should not automatically involve reanalysis and thus not be more difficult than subject-gap, except for individuals with a deficiency in using morphological markers as disambiguating cues, such as certain clinical populations.

An alternative non-resource capacity approach attributes the greater difficulty of object-gap RCs to their non-canonical word order, making them more challenging for individuals with impaired ability to represent grammatical information (Caplan & Waters, 1999). According to this approach, sentences with a canonical word order can be interpreted without relying on grammatical markers by using a default heuristic, i.e., assigning two successive arguments the roles of Agent and Theme respectively based on their linear order. In sentences with an altered word order, without semantic cues (e.g., as in fully semantically reversible RCs), grammatical markers must be solely relied on for syntactic and semantic analysis, making them more error-prone.

Another non-resource-based approach attributes the greater difficulty of the object-gap RCs to a frequency/regularity effect, i.e., complexity arising from lower frequency and greater irregularity of non-canonical word orders (Kidd, Brandt, Lieven, & Tomasello, 2007; MacDonald & Christiansen, 2002). This approach maintains that individual differences in comprehension accuracy are an emergent property of the network architecture (its overall efficiency and the quality of its individual facets) interacting with experience (exposure to input of varying frequency and regularity). In English, subject-gap RCs have the same word order as active declarative clauses, unlike object-gap RC. Consequently, the former have higher frequency and regularity than the latter, and are expected to give rise to higher accuracy.

In sum, higher processing complexity of certain RC types has been explained by greater memory demands, violations of expectations, non-canonical word order, and lower frequency4. In English, both resource- and non-resource-based approaches predict greater complexity of object- versus subject-gap RCs. Fixed word order and the absence of overt case markers make it difficult to differentiate the effects of working memory from the effects of other potential sources of syntactic complexity. Languages with rich morphology and a flexible word order allow us to remove these confounds and isolate the roles of these factors, thus offering more precisely targeted probes into language processing in young TD children and clinical populations, including children with DLD.

1.4 Relative Clause comprehension in Children with DLD

Children with DLD exhibit deficits in production of grammatical morphology (Bedore & Leonard, 2001; Dromi, Leonard, Adam, & Zadunaisky-Ehrlich, 1999; Leonard & Bortolini, 1998; Leonard & Eyer, 1996; Penke, 2009) as well as in comprehension and production of complex structures, including RCs, demonstrated in a variety of languages, such as English, Hebrew, Greek, and Swedish (Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004, 2007; Hakansson & Hansson, 2000; van der Lely & Harris, 1990; Novogrodsky & Friedmann, 2006; Schuele & Nicholls, 2000; Stavrakaki, 2001). They were found to underperform to a greater extent on object-gap RCs (Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004; Adani, Forgiarini, Guasti, & van der Lely, 2014), and exhibit no on-line gap-filling effects during a cross-modal priming task, unlike TD controls (Hestvik, Schwartz, & Tornyova, 2010). However, they showed greater accuracy for sentences with dissimilar number features (i.e., one singular, one plural) on the head noun and the embedded DP (Adani et al., 2014).

Other complex structures comprehension of which is difficult for children with DLD include object wh-questions (Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2011; van der Lely, 1996; van der Lely & Battell, 2003; van der Lely, Jones, & Marshall, 2011; Marinis & van der Lely, 2007), verbal passives (Adams, 1990; Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2007; Marshall, Marinis, & van der Lely, 2007), topicalization, focalization, and dative shift (van der Lely & Harris, 1990). These structures are typically analyzed as derived by phrasal movement, i.e., characterized by a non-canonical order of arguments requiring linking the gap and the NP in its displaced position via a chain. A deficit in the representational knowledge of the linguistic mechanisms involved in establishing grammatical relations in such sentences would lead to impaired comprehension.

Indeed, a number of studies have attributed difficulties with interpreting RCs and other complex structures in children with DLD to a syntactic deficit, henceforth the syntactic deficit view. These proposals include an optionality of syntactic movement (van der Lely, 1998), an inability to assign θ-roles through the trace to the moved element (Friedmann & Novogrodsky, 2004; Stavrakaki, 2001) or a general deficit in computing/representing complex syntactic dependencies (van der Lely, 2005)5.

In opposition to the syntactic deficit view is a view attributing linguistic difficulties in DLD to deficits in the general perceptual or cognitive processing systems (e.g., Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990; Ullman & Pierpont, 2005), henceforth processing deficit view. The studies within the processing deficit view of DLD mainly focus on the aspects of language other than comprehension of complex syntax, e.g., deficits in grammatical morphology and vocabulary. However, insufficient phonological or verbal working memory resources (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990) have been used as an explanation for the diminished capacity to process complex syntactic structures in children with DLD (Montgomery, 2000).

Another approach explains grammatical difficulties of children with DLD as a consequence of their weakness in extracting patterns and making generalizations with respect to surface morphology (henceforth, morphological deficit view), attributed to a deficit in the procedural memory system (Conti-Ramsden & Jones, 1997; Lum, Gelgic, & Conti-Ramsden, 2010; Ullman & Pierpont, 2005). Under this view, a less well-developed system of morphological categories or exponents would interfere with sentence comprehension, particularly, in languages with rich morphological systems and structures with a non-canonical word order and where interpretive heuristics cannot be relied on (i.e., interpretation cannot rely solely on lexical semantic and encyclopedic knowledge), but one must rely on grammatical morphology to perform syntactic and semantic analysis.

RCs can serve as an effective probe into language capacity of children in DLD, as they afford us with an opportunity to observe whether specific complexity inducing factors of RC structure as discussed above (e.g., clause interruption, case mismatch, and/or non-canonical word order) induce a greater processing detriment in children with DLD relative to their typically developing age peers.

1.5 Relative Clause Acquisition in Typically Developing Children

Typically developing (TD) children use RCs, initially in a structurally simplified form, in their spontaneous speech as early as 2.5–3 years of age (Diessel & Tomasello, 2000), but in experimental studies display difficulties in RC comprehension until 5–6 years of age and beyond (for a review, see Adani, 2011; Kidd, 2003). The acquisition literature on RC is extensive and includes discussions on the age at which (and via what mechanisms) children develop full competence of the RC grammar and the factors that influence children’s performance on RC comprehension in addition to syntactic knowledge. The early literature was focused on whether 4–6-year-old children possess the capacity to build complex recursive structures and whether they were sensitive to the factors identified as sources of processing complexity for adults. Early studies were somewhat inconsistent (de Villiers, Tager Flusberg, Hakuta, & Cohen, 1979). One study (Sheldon, 1974) found no effect of gap position or the grammatical function of the RC head, but found an effect of parallel function. These findings, however, were not fully replicated (Tavakolian, 1981). Non-adult-like performance of young children was attributed to relying on parsing heuristics (de Villiers et al., 1979) or analyzing the RC and a conjoint clause (Tavakolian, 1981).

Subsequently, however, the greater difficulty of object-gap compared to subject-gap RCs in head-initial languages was amply documented (e.g., Adani, 2011; Arosio, Guasti & Stucchi, 2011; Corrêa, 1995). Although the age at which TD children develop full syntactic knowledge of RCs is not fully resolved (cf. Goodluck & Stojanovic, 1996; Goodluck & Tavakolian, 1982; Hamburger & Crain, 1982; Kidd & Bavin, 2002; Labelle, 1996; Sheldon, 1974), there is converging evidence that children’s knowledge of RC grammar is likely to be underestimated in experiments if certain factors complicating RC processing are not controlled for. For example, Hamburger and Crain (1982) argued that children’s performance is hindered by having to interpret restricted RCs in contexts that do not satisfy the presuppositions associated with restrictive RCs, namely that the set of entities referred to by the RC head contains more than one entity. In addition, since the event denoted by the RC verb is interpreted as having occurred before the event denoted by the matrix verb, for young children this complicates processing RCs with the surface order of the relative and matrix clause predicates being the reverse of the temporal order of the two events (i.e., right-branching RCs), particularly if the required response must incorporate both events. It was also found that RC sentences with two rather than three NPs (Goodluck & Tavakolian, 1982), inanimate RC heads, and pronominal RC subjects (Arosio, Guasti, & Stucchi, 2011; Friedmann, Belletti, & Rizzi, 2009) are easier to process, and that working memory, measured by digit span, modulates children’s performance (Arosio, Guasti, & Stucchi, 2011). Finally, there is evidence that children apply the same parsing strategies as adults, e.g., reactivate displaced constituents at gap positions when processing syntactic dependencies (Felser & Clahsen, 2009).

In sum, it appears, that TD children around the age of 6 (or possibly before) develop full knowledge of RC grammar and adult-like parsing strategies, but lack pragmatic skills and resource capacity to process them efficiently (see Clahsen & Felser, 2006; Felser & Clahsen, 2009, for a review).

1.6 Relative Clause Acquisition in Morphologically Rich Languages

Cross-linguistic studies of RC acquisition largely corroborated the complexity effects of the structural factors observed in English, including clause interruption, non-parallel function, filler-gap distance, word order, and construction frequency (Özge, Marinis, & Zeyrek, 2009; Kas & Lukács, 2012; Macwhinney & Pleh, 1988). Such studies also documented a relationship between structural factors influencing sentence processing and children’s working memory capacity (e.g., Kas & Lukács, 2012; Arosio, Yatsushiro, Forgiarini, & Guasti, 2012).

One issue that received much attention in recent literature was the role of morphological markers as disambiguating cues during RC processing by young children. The results of this line of work have been somewhat mixed. Thus, a study of Romanian-speaking preschool-aged children compared their performance on object-gap RCs with an overtly case-marked relative pronoun with those in which the relative pronoun was not case-marked and found no difference in accuracy (Bentea, 2012). In contrast, Greek-speaking 4–6-years old children showed an improved comprehension accuracy of object-gap RCs when the RC subject was unambiguously, rather than ambiguously, case-marked (Guasti, Stavrakaki, & Arosio, 2012). Evidence that children use morphological marking as a disambiguating cue in interpreting subject- and object-gap RCs was also obtained in German (Arosio, Yatsushiro, Forgiarini, & Guasti, 2012). Furthermore, a study of Japanese found that although object-gap RCs in this head-final language generally present less difficulty to preschool-aged children than subject-gap RCs, this contrast disappears in those children who perform well on a case-marker test in which children had to use nominative and accusative case markers as interpretive cues in a picture selection task (Suzuki, 2011).

A number of studies within the syntactic framework of Relativised Minimality (Rizzi, 1990) examined the role of grammatical dissimilarity between the RC head and the embedded DP, including the effect of number (Adani et al., 2010) and gender (Belletti et al., 2012) features dissimilarity. In a study comparing Hebrew and Italian by Belletti and colleagues (Belletti, Friedmann, Brunato, & Rizzi, 2012), differential gender marking facilitated RC comprehension in Hebrew, a language in which verbs have gender agreement marking, but not in Italian, a language in which they don’t. These results suggest that it is not merely the grammatical similarity of the two NPs, but also the featural composition of the clausal functional head that plays a facilitative role in RC comprehension by TD children.

Literature on the comprehension of RCs in Russian is rather scarce and is focused on monolingual adults (Levy, Fedorenko, & Gibson, 2013) and English-dominant heritage speakers of Russian, adults and children (Polinsky, 2011). The latter study included Russian-speaking TD children as controls and found that by the age of 6, monolingual children showed mastery of both subject- and object-gap RCs (over 85% correct). The high level of performance of this study can be attributed to the experimntal design: the stimuli were semantically reversible RC sentences containing two NPs, animate and inanimate (e.g., “Where is the cat that is chasing the dog?”; “Where is the bicycle that is circling the car?”) each paired with 2 picture options. Further research is needed to understand more fully what structural factors influence RC processing in Russian-speaking children and the extent to which they are related to working memory demands.

1.7 Russian Sentences with Relative Clauses

Like in English, Russian RCs are modifying clauses with an external head preceding the RC. They contain a gap at the relativization site and a relative pronoun linked with the gap. However, there are important differences between Russian and English RCs. First, unlike English, Russian nouns and their dependents are inflected for gender/number. The relative pronoun shares gender/number features with the RC head, providing a morphological cue helping establish reference for the gap. Next, all nouns and their modifiers are case marked, making their grammatical/thematic roles identifiable even when NPs are displaced from their canonical positions. The head NP is case marked according to its syntactic role in the matrix clause, and. the relative pronoun according to the syntactic position of the gap – with the nominative case in subject-gap RCs and accusative case in object-gap RCs. If its grammatical function is parallel to that of the RC head, the two are case-matched (e.g., both nominative, as in (5) or accusative, as in (6)). If, however, their functions are non-parallel, they would be case-mismatched: with a nominative head - accusative relative pronoun in object-gap CE, as in (7), and accusative head - nominative relative pronoun in subject-gap RB, as in (8). Thus, unlike in English, in Russian RCs do not contain a local ambiguity, as case marking of the relative pronoun immediately indicates the gap position.

| (5) |

Case match in subject-gap CE Kuritsa kotoraja klyunula gus’a uščipnula utku chickenfem_nom which-fem_nom peckedfem goose-masc_acc pinchedfem duckfem-acc “The chicken that pecked the goose pinched the duck.” |

| (6) |

Case match in object-gap RB Kuritsa klyunula gus’a kotorogo uščipnula utka chickenfem_nom peckedfem goosemasc_acc whichmasc_acc pinchedfem duckfem_nom “The chicken pecked the goose that the duck pinched.” |

| (7) |

Case mismatch in object-gap CE: Kuritsa kotoruju klyunul gus’ uščipnula utku chickenfem_nom whichfem_acc peckedmasc goosemasc_nom pinchedfem duckfem_acc “The chicken that the goose pecked pinched the duck.” |

| (8) |

Case mismatch in subject-gap RB: Kuritsa klyunula gus’a kotoryj uščipnul utku chickenfem_nom peckedfem goosemasc_acc whichmasc_nom pinchedmasc duckfem_acc “The chicken pecked the goose that pinched the duck.” |

Another relevant aspect of Russian grammar is the word order. The basic word order in Russian is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO; Bailyn, 1995; Kondrashova, 1996); however, any order of the verb and its arguments is possible. RCs, either object- or subject-gap, allow various word orders, but the pragmatically neutral and the most frequent word order (Levy, Fedorenko, & Gibson, 2013)6 for subject-gap RCs is SVO, as in (9), and for object-gap OVS, as in (10).

| Subject Verb Object | |

| (9) | Kuritsa1 kotoraja1 klyunula utku …. chickenfem_nom whichfem_nom peckedfem duckfem_acc “The chicken that pecked the duck…” |

| Object Verb Subject | |

| (10) | Kuritsa1 kotoruju1 klyunula utka2 …. chickenfem_nom whichfem_acc peckedfem duckfem_nom “The chicken that the duck pecked…” |

Thus, as in English, subject-gap RCs have the canonical SVO, while object-gap RCs a non-canonical OVS word order. Like in English, the two RC types differ with respect to the depth of embedding, with the subject-gap being less deeply embedded. However, unlike in English, both types of RCs are “local” in the sense that no NP intervenes between the relative pronoun and the gap, with the verb immediately following the relative pronoun in both types of RC.

Since both subject- and object-gap RCs are equalized with respect to intervening NPs, the factor of gap in Russian, rather than tapping into memory-capacity effects, can be considered an indicator of the word order effects. Case/thematic-role mismatch effect would be consistent with the effect of non-parallel function (previously related to resource capacity (King & Just, 1991), but in a language like Russian, likely to also be related to morphological processing. Finally, embedding type can be treated as an index of working memory load.

2. Goals and Predictions

The first aim of the present study was to evaluate various (non-mutually exclusive) theories of syntactic complexity, as discussed above by examining performance of Russian-speaking children and adult controls on various types of RCs. In particular, we sought to test resource capacity, word order, and Case matching theories. The four types of RCs in Russian (subject-gap CE, object-gap CE, subject-gap RB, and object-gap RB) with their neutral word order allow us to examine the relative contribution of two fully crossing factors - position of the gap and embedding type. The four types of RCs vis-a-vis the potential complexity factors they contain are summarized in Table 1. We can formulate the following predictions with regards to expected complexity effects:

If extra complexity is triggered by the non-canonical word order, object-gap sentences (conditions 2 and 4 in Table 1) are expected to present greater difficulty relative to subject-gap (conditions 1 and 3). This would be manifested as a main effect of gap.and would not be attributable to a greater memory load, as these sentences contain no intervening NPs, similar to subject-gap sentences, and hence are equalized with them in terms of storage and integration costs.

If extra complexity is due to a greater memory load associated with clause interruption, we expect center-embedded sentences (conditions 1 and 2) to be of greater difficulty relative to right branching (conditions 3 and 4). This would be manifested as a main effect of embedding.

The factor of Case Mismatch is interwoven with the other two factors and cannot be systematically varied within each combination of Embedding and Gap factors, i.e., Case Mismatch is limited to subject-gap RB and object-gap CE, while Case Match is limited to subject-gap CE and object-gap RB. Therefore, the Case Matching theory (Sauerland & Gibson, 1998) would predict greater difficulty of RCs with non-parallel cases (nominative-accusative and accusative-nominative; conditions 2 and 3) relative to conditions with parallel (nominative-nominative and accusative-accusative cases; conditions 1 and 4). This would be manifested as an interaction between Gap and Embedding.

Because multiple effects may be present, they may additive impact making Object-gap CE condition markedly more difficult than the other three condition, as it combines all three complexity features, while the other three types of RCs are characterized by one complexity feature each: center-embedding for subject-gap CE, case-mismatch for subject-gap RB, and non-canonical word order for object-gap RB.

Table 1.

Properties of four different types of RCs in Russian

| Type | Gap Position | Embedding | Intervener between the gap and the filler | Non-canonical Word Order | Case Mismatch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Subject-gap | Center-embedded | No | No | No |

| 2. | Object-gap | Center-embedded | No | Yes | Yes |

| 3. | Subject-gap | Right-branching | No | No | Yes |

| 4. | Object-gap | Right-branching | No | Yes | No |

Note: Greater difficulty of object-gap sentences relative to subject-gap (manifested as a main effect of Gap) would provide support for the impact of non-canonical word order; greater difficulty of center-embedded sentences relative to right branching (manifested as a main effect of embedding) would indicate that extra complexity is due to clause interruption and consequently a greater working memory load; greater difficulty of RCs with non-parallel cases (i.e., manifested as an interaction between Gap and Embedding) would provide support for the Case Matching theory.

Our second aim was to identify sources of language deficits in DLD by comparing the effects of various complexity factors on two groups of age matched children: those with and without DLD. Given previously reported deficits in working memory, grammatical morphology, and comprehension of syntactic structures with long-distance dependencies, we expect them to underperform overall. In addition, we can formulate the following predictions:

-

1a

If a core deficit in DLD is related to processing non-canonical word orders (displaced constituents), or, more generally, representing long-distance dependencies, the DLD group should be disproportionately more error-prone on object-gap RCs, manifested as a Group-by-Gap interaction.

-

2a

If the core problem in DLD is reduced working capacity, the DLD group should have disproportionate difficulty interpreting sentences with higher storage/integration costs and underperform on the CE conditions, manifested as a Group-by-Embedding interaction.

-

3a

If children with DLD have special difficulties processing non-parallel function and/or a sequence of incongruently case marked NPs, we expect them to have extra difficulty with Case-mismatch sentences, manifested as a Group-by-Gap-by Embedding interaction.

These predictions would also apply to the TD children when compared to adults, and we can ask whether it is the capacity to process non-canonical word orders, center-embedded structures or case mismatch/non-parallel functions that has to develop for TD children to reach adult-like level of performance. We explored these predictions cross-sectionally comparing the performance of children with DLD with that of typically developing children, and the latter with a normative sample of adults.

3. Method

3.1 Population

Children with DLD in the current study come from a small Russian-speaking population, which has been the focus of a genetic and epidemiological study of DLD described elsewhere (Rakhlin et al., 2012) because of the unusually high rates of atypical language development despite the absence of apparent other developmental, neurobiological or sensory pathology, as ascertained by medical records, neurological and psychiatric screenings, and an evaluation by a certified clinical geneticist. At the time of this study, the population consisted of 861 individuals, including 138 children between the ages of 3 and 18. Our investigation revealed that about 30% of school-aged children have expressive grammar deficits, in contrast to the 8% impaired in the comparison population (a rural population from the same geographic region matched on dialectal, educational, cultural and socio-economic variables).

3.2 Participants

For the present study, we have recruited three samples: 1) children with DLD from the population described above, 2) their TD peers recruited from a comparison population, and 3) a healthy group of adults. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Out of the 44 participating schoolchildren (17 girls, 27 boys; age range: 5.08 to 15.83; M = 10.67, SD = 2.84), 22 were TD (age range: 7.08 – 15.25; M = 10.69, SD = 1.86; 10 girls, 12 boys) and 22 were identified as DLD (age range = 5.08 – 15.83; M = 10.67, SD = 3.62; 7 girls, 15 boys). Children with DLD were recruited based on their performance on a narrative task (see below), absence of co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorders or hearing impairment, and non-verbal IQ above the cut-off for intellectual disability. The groups did not differ with respect to their mean age, t(42) = .02, p = .99, and gender distribution, χ2(1) = .86, p = .35. The sample of TD children was recruited following teachers’ referrals of children with no language, reading or academic difficulties. Recruitment of both samples was carried out through the local kindergartens, elementary and secondary schools.

All of the children included in the DLD group displayed standardized nonverbal intelligence scores above 75 (M = 92.18, SD = 10.33), measured by either the Cattell’s Culture-Fair Intelligence Test Scale 2 (CFIT; Cattell & Cattell, 1973) or the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT; Bracken & McCallum, 1998). Both tests assess nonverbal (or fluid) intelligence and were administered individually. Because CFIT Scale 2 is for children 7 to 18 years old, UNIT was used with five children below the age of 7, whereas CFIT was used with the remaining thirty-nine children. None of the children were diagnosed with autism, Down syndrome, hearing impairment or any other genomic and/or developmental disorder.

To establish the normative adult-level performance on the RC comprehension task and to be able to comparatively evaluate TD children’s performance, we recruited a sample of 22 adults (age 17.42 to 31.42, M = 21.36, SD =3.57, 7 male, 15 female).

3.3 Language assessment

Since no published validated standardized language development assessments were available for Russian at the time of the study, we used a narrative task, a valid measure of language development (e.g., Botting, 2002; Norbury & Bishop, 2003), as the main tool of language assessment for ascertaining children’s DLD status. We used two wordless storybooks, Frog, Where Are You? and One Frog Too Many (Meyer, 1969) for children under 13 and Free Fall (Wiesner, 2008) and Tuesday (Wiesner, 1997) for those over 13. The audio and the transcripts were rated on a number of characteristics relative to the performance of age peers from a comparison normative population (Rakhlin et al., 2012). For the purposes of the present study, we used children’s scores on the two measures of expressive grammar: Wellformedness (frequency of ill-formed sentences) and Syntactic Complexity (frequency of embedded and conjoined clauses, passives, and participial constructions) using age-adjusted robust z-scores. The DLD group was comprised of the children who performed at the level below −1 SD from the mean of the normative comparison group on Wellformedness (n=17) or Syntactic Complexity (n=4), or both (n=1).

3.4 Working memory assessment

To assess working memory span, we used a forward and backward Digit Span task (Cronbach’s α = .89) modeled after the analogous subtest of Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III; Wechsler, 1991). Each sub-task included 2 practice items, passed by all children, and 16 test items split into 8 blocks of 2 items each (32 items in total for both parts of the task). The items were progressively increasing sequences of digits (from 2 to 8), with the sum of all correctly repeated sequences comprising the total score. The test was discontinued after an error in both items within a block.

3.5 RC comprehension task

To measure comprehension of RCs, we used fully semantically reversible RC sentences of the four types listed in Table 1: CE subject-gap, CE object-gap, RB subject-gap, and RB object-gap illustrated in (11)–(14).

| (11) | Kuritsa kotoraja klyunula utku uščipnula voronu chickenfem_nom whichfem_nom peckedfem duck-fem_acc pinchedfem crowfem_acc “The chicken that pecked the duck pinched the crow” |

| (12) | Kuritsa kotoruju klyunula utka uščipnula voronu chicken-fem_nom which-fem_acc peckedfem duck-fem_nom pinched-fem crow-fem_acc “The chicken that the duck pecked pinched the crow.” |

| (13) | Kuritsa klyunula utku kotoraja uščipnula voronu chickenfem_nom peckedfem duckfem_acc whichfem_nom pinchedfem crowfem_acc “The chicken pecked the duck that pinched the crow.” |

| (14) | Kuritsa klyunula utku kotoruju uščipnula vorona chickenfem_nom peckedfem duckfem_acc whichfem_acc pinchedfem crowfem_nom “The chicken pecked the duck that the crow pinched.” |

Each sentence had transitive verbs in both the matrix clause and the RC, and thus contained 3 NPs. The gender was kept uniform across all NPs in each sentence to eliminate gender agreement cues on the verb. All NPs were animate and fully reversible thus presenting a high level of processing complexity, appropriate for the participants in our age range. The items were balanced between feminine and masculine, as well as between action and perception verbs.

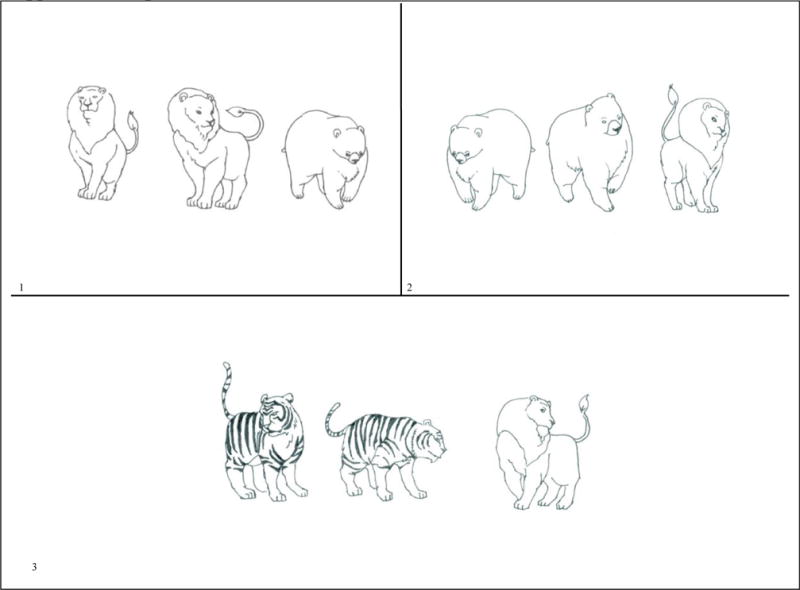

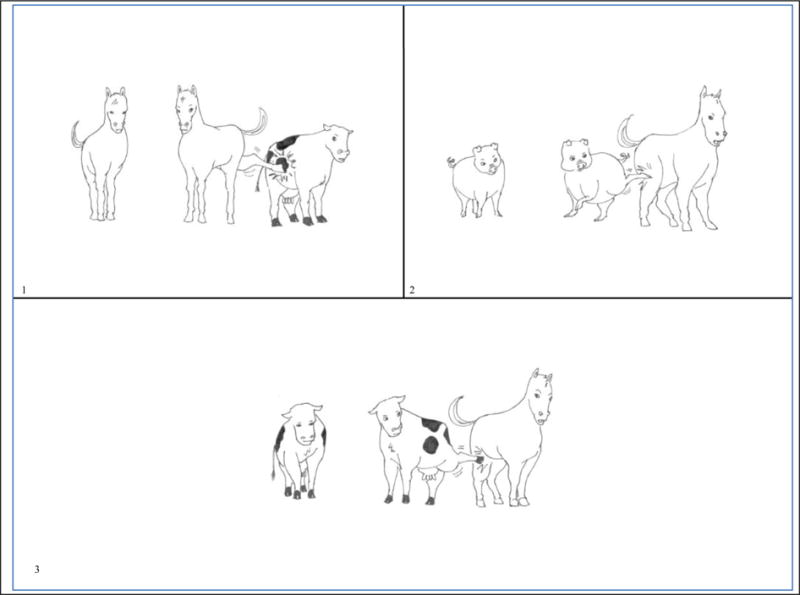

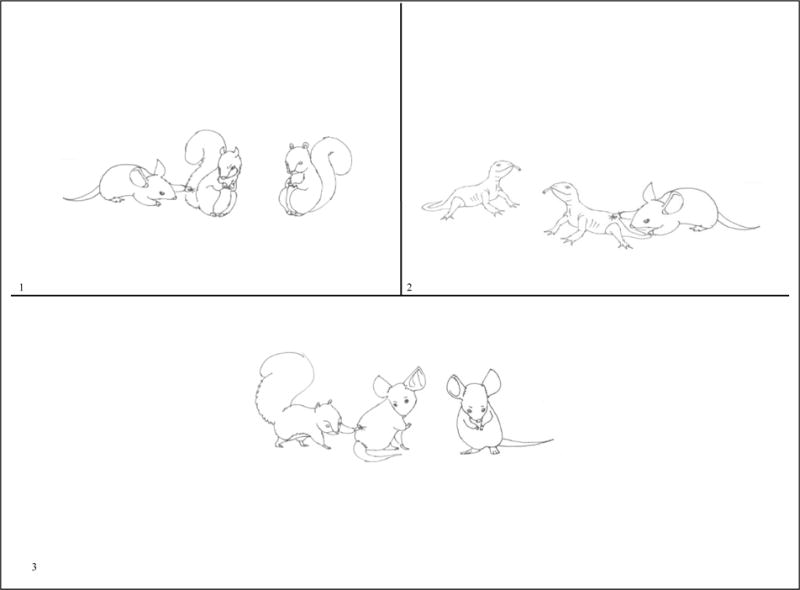

Each trial consisted of an auditorily presented sentence (read by a native Russian speaker) paired with three pictures: 1) the RC agent performing an action on the RC theme, 2) the same action but with the roles reversed, and 3) a foil. The target picture depicted only the event denoted by the RC verb (and its respective participants), and did not include the event demoted by the matrix verb (and an additional participant), to alleviate the difficulty of having to depict two events with potentially different temporary orders. Thus, the target picture for the test item analogous to (11) would only depict the RC part of the sentence, i.e., a chicken pecking a duck, with an extra individual of the type denoted by the RC head (an additional chicken in this case) added to the picture to satisfy the presupposition associated with a restrictive RC and to make the use of restricted RC sentences pragmatically felicitous (Hamburger & Crain, 1982). To keep the structure of all picture options uniform, each picture contained an additional individual corresponding to one of the other two NPs in the sentence (one contained in the RC clause and another one irrelevant to the interpretation of the RC clause). See the Appendix for the sample items.

The children were instructed to listen to each sentence and choose the picture that goes best with its meaning. They were also told that the picture would only show some, but not all, of the characters described in each sentence. There were eight items in each of the four conditions with a total of 32 items, plus three training items: simple sentences with di-transitive verbs. The same methodology was used with adults.

The experiment had a 3 × 2 × 2 design: Group (adults, TD, DLD) × Embedding (center embedded and right branching) × Gap (subject-gap and object-gap), with Case (match/mismatch) naturally interlaced in the embedding/gap crossing. Including NP gender (masculine vs. feminine) and verb type (action vs. perception) as factors in the analysis did produce significant effects and did not improve model fit (all p’s > .200). Therefore, we will only report the main results with Embedding, Gap Position, and Group as factors.

4. Results

The descriptive statistics representing raw scores are presented in Table 2. The at-chance level of performance was 33%. The groups significantly differed from each other on working memory, F(2,63) = 85.63, p < .001, η2partial = .73, with the lowest scores in the DLD group and the highest in the adults (all pairwise FDR-adjusted p’s < .001).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Measures

| Adults | Children with TD | Children with DLD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 21.36 | 3.57 | 10.69 | 1.86 | 10.67 | 3.45 |

| vSTM | 23.50 | 4.02 | 14.82 | 2.38 | 9.18 | 4.27 |

| Sub CE | 6.73 (84%) | .98 (12%) | 5.18 (65%) | 1.87 (23%) | 3.36c (42%) | 1.87 (23%) |

| Obj CE | 6.91 (86%) | .87 (11%) | 3.18c (40%) | 1.94 (24%) | 2.09bc (26%) | 1.11 (14%) |

| Sub RB | 6.14 (77%) | 1.58 (20%) | 3.45 (43%) | 1.63 (20%) | 3.36 (42%) | 1.47 (18%) |

| Obj RB | 6.77 (85%) | 1.15 (14%) | 4.45 (56%) | 1.89 (24%) | 3.63 (45%) | 2.01 (25%) |

Note. vSTM – verbal short term memory (digit span); Sub CE – Subject Center-embedded relative clauses, Obj CE – Object Center-embedded, Sub RB – Subject Right-branching, Obj RB – Object Right-branching. The values represent average accuracy scores; % correct responses are given in parentheses.

– performance not significantly different from chance based on a set of 2-tailed one-sample t-tests performed separately for each group and condition.

- performance below chance.

We analyzed the data using a mixed 2 (Embedding) × 2 (Gap) × 3 (Group) mixed logit model fitted at the item-level data with crossed random effects for items and subjects. Mixed effects logit models are generalized linear mixed models, which employ a logit link function designed for binomially distributed dependent variables, such as accuracy. Each model describes the outcome as a linear combination of fixed effects (e.g., substantive independent variables and covariates, the effects of which are thought to hold across the whole sample) and random effects (e.g., subject- and item-specific effects that model the variability at the respective levels). This approach has several key advantages over traditional ANOVA approaches (for more details, see Dixon, 2008; Jaeger, 2008; Quené & van den Bergh, 2008) applied to (transformed) average accuracy scores. Although all of the effects were examined in the framework of a single statistical model, for ease of exposition, we will first present and discuss the baseline results for the TD children relative to adults, before presenting the results for the DLD relative to the TD group.

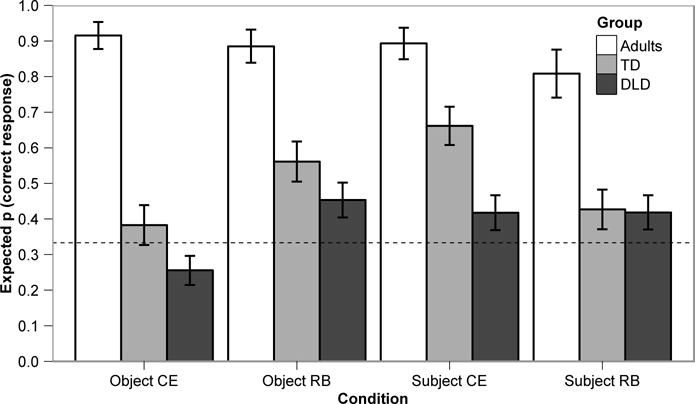

The modeling of conditional response probabilities for dichotomous accuracy variable (0=incorrect, 1=correct) at the item level was performed in R using the lmer function from the lme4 library (Bates & Maechler, 2010) with Laplace approximation. The effect of Gap was dummy-coded7 as 0=Object, 1=Subject, while that of Embedding was dummy coded as 0=Center-Embedded, 1=Right-Branching. Working memory scores were centered prior to being included in the models as a continuous predictor using the mean of TD children. Thus, the intercept represented the estimated log odds of a correct response of TD children on the Object CE condition at the average level of working memory, and the regression parameters for the fixed effects represented changes in the log odds that corresponded to the respective changes in the levels of within- and between-subjects dichotomous experimental and continuous predictors. Expected probabilities of correct responses of the three groups (adults, children with TD, and children with DLD) on the four types of RC sentences based on the models presented in Table 3, performed separately for each group, are shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Summary of the fixed effects in two mixed logit models (with and without memory as a covariate)

| Model | Fit | Predictor | Coef. | SE | Wald Z | p > |Z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not controlling for vSTM M2 | −2LL = 2439 | |||||

| χ2(11) = 110.15 | Intercept | −.454 | .246 | −1.843 | .065 | |

| p < 2.2e−16 | Embedding = RB | .708 | .311 | 2.275 | .023* | |

| Gap = Sub | 1.146 | .316 | 3.624 | <.001*** | ||

| Group = Adults | 2.453 | .318 | 7.705 | <.001*** | ||

| Group = DLD | −.656 | .282 | −2.324 | .020* | ||

| RB : Sub | −1.699 | .443 | −3.835 | <.001*** | ||

| RB : Adults | −.849 | .385 | −2.209 | .027* | ||

| RB : DLD | .204 | .323 | .633 | .527 | ||

| Sub : Adults | −1.265 | .389 | −3.250 | .001** | ||

| Sub : DLD | −.406 | .331 | −1.227 | .220 | ||

| RB : Sub : Adults | 1.256 | .530 | 2.371 | .018* | ||

| RB : Sub : DLD | .813 | .454 | 1.788 | .074 | ||

| Controlling for vSTM M3 | −2LL = 2435 | |||||

| χ2(15) = 114.98 | Intercept | −.454 | .246 | −1.845 | .065 | |

| p < 2.2e−16 | Embedding = RB | .707 | .311 | 2.271 | .023* | |

| Gap = Sub | 1.147 | .317 | 3.621 | <.001*** | ||

| Group = Adults | 1.977 | .431 | 4.583 | <.001*** | ||

| Group = DLD | −.352 | .340 | −1.036 | .300 | ||

| vSTM | .056 | .035 | 1.583 | .114 | ||

| RB : Sub | −1.698 | .443 | −3.830 | <.001** | ||

| RB : Adults | −.172 | .518 | −.331 | .743 | ||

| RB : DLD | −.227 | .391 | −.579 | .562 | ||

| Sub : Adults | −.757 | .523 | −1.447 | .148 | ||

| Sub : DLD | −.730 | .399 | −1.831 | .067 | ||

| RB : vSTM | −.079 | .041 | −1.938 | .053 | ||

| Sub : vSTM | −.060 | .041 | −1.451 | .147 | ||

| RB : Sub : Adults | .728 | .717 | 1.015 | .310 | ||

| RB : Sub : DLD | 1.144 | .548 | 2.087 | .037* | ||

| RB : Sub : vSTM | .061 | .055 | 1.108 | .268 |

Note. ‘:’ indicates an interaction term.

- p < .05,

- p < .01,

- p < .0001.

−2LL - −2 log-likelihood (deviance). RB - right-branching, Sub - subject gap, vSTM – verbal short-term memory (Digit Span), DLD – Developmental Language Disorder. Fit indices are presented relative to the null model with just random effects of items and subjects on the intercept.

Figure 1.

Expected probabilities of correct responses of three groups (adults, children with TD, and children with DLD) on the four types of RC sentences (with standard error bars; based on individual models presented in Table 4): Subject CE – subject-gap center-embedded, Object CE – object-gap center-embedded, Subject RB – subject-gap right-branching, Object RB – object-gap right-branching. The horizontal dashed line represents chance level of performance.

The first model (M1) included the fixed effects of Embedding, Gap, and Group, as well as random effects of subjects and items on the intercept. The model displayed a significantly better fit than the null model (M0) with just random intercepts (log-likelihood = −1220; χ2(11) = 110.15, p < .0001). To investigate the effects of working memory on RC performance, we fit the second model (M2) to the data. M2, in addition to the fixed effects of Gap, Embedding, and Group, included the fixed effect of working memory and its interactions with Gap and Embedding, to allow for specificity in the effects of working memory on performance in different experimental conditions. We will now describe the results from both models separately comparing the performance of the adults and TD children and that of TD children and children with LD. Table 3 summarizes the fixed effects in the two mixed logit models (with and without memory as a covariate).

4.1 RC Comprehension in Typically Developing Children and Adults

Adults showed a markedly higher accuracy than TD children (Estimate = 2.45, p < .001). All possible group interactions were also significant (at p < .05) suggesting that the effects of Gap and Embedding differed between the TD children and adults. For the TD children, the effect of Embedding was significant (Estimate = .71, p = .023) indicating better accuracy on RB compared to CE conditions. The effect of Gap was also significant (Estimate = 1.15 p < .001), with better performance on the subject-gap compared to object-gap conditions. The interaction between Gap and Embedding (representing Case effect) was also significant (Estimate = −1.70, p < .001) and indicated lower accuracy on the case-mismatch conditions. The magnitude of the parameter estimates for the significant interactions between Group=Adults and Embedding (Estimate = −.85 p = .027), Gap (Estimate = −1.27 p < .001) and Gap-by-Embedding interaction (Estimate = 1.26 p = .018) is nearly identical to the magnitude of these effects for the TD children, but opposite in direction, indicating that adults do not show these effects (corroborated by the analyses performed separately for adults; data not shown), and their performance on all conditions is essentially the same.

After controlling for memory (Estimate = .06, p = .113), the effect of Group=Adults remained significant (Estimate = 1.98, p = .006) suggesting that the differences in overall performance between TD adults and children could not be fully explained by the differences in their working memory capacity. The inclusion of working memory as a covariate in the model rendered the group-related interactions described above insignificant, indicating that group differences in working memory accounted for the differences in the patterns of performance between the TD children and adults and suggesting that both groups were sensitive to the same grammatical and processing constraints, when differences in working memory are controlled for.8 At the same time, working memory differences could not fully account for the overall quantitative difference in accuracy between the two groups, suggesting that achieving a full adult-like performance level on RC processing involves additional aspects of cognitive development, not captured in the present study design.

In sum, these results indicate that: 1) TD children with the mean age of ≈10.6 still did not reach adult-level RC processing; 2) their performance was negatively affected by object-gap, center-embedding, and case mismatch, while the adults were not affected by any of these features; 3) differences in working memory accounted for the qualitative differences in RC performance between TD children and adults; however, the overall lower performance of children relative to adults was not fully explained by their lower working memory.

4.2 RC Comprehension in Children with DLD and TD

With respect to differences in accuracy between the two groups of children, an examination of parameter estimates for M1 revealed a significant main effect of Group (Estimate = −.66, p = .020), indicating that children with DLD underperformed on RC comprehension overall compared to TD children. No Group=DLD-related interactions were significant.

When controlled for working memory (model M2), the main effect of group lost significance and decreased in size (Estimate = −.35, p = .300), suggesting that the overall quantitative difference between the DLD and TD groups was to a large extent attributable to differences in working memory. However, this analysis also revealed that, after controlling for working memory, the two groups displayed some qualitative differences in performance. Specifically, the three-way interaction between Embedding, Gap and Group=DLD reached statistical significance (Estimate = 1.14, p = .037). Taken together with the estimate for the two-way interaction between Embedding and Gap, i.e. the effect of Case (dummy-coded in the model as an interaction term for children with TD; Estimate = −1.70, p < .001), this result indicated that the effect of Case was substantially smaller for children with DLD compared to children with TD. Thus, while children with TD displayed a marked decrease in accuracy in the case mismatch conditions relative to the case match, children with DLD did not exhibit such contrast. These results are further supported by the differences in the magnitudes and statistical significance of respective parameters from the models ran separately for each group (data not shown).

In sum, our results indicate that: 1) children with DLD significantly underperformed on RC processing relative to their TD age-matched peers; 2) the quantitative difference between the two groups could be largely explained by the differences in working memory; 3) however, after controlling for working memory differences, qualitative dissimilarities in the pattern of RC processing between the two groups emerged, namely the effect of Case was found to be smaller in children with DLD compared to the TD group. This suggests that what underlies group differences in RC processing accuracy between TD and DLD groups is not only differences in working memory, which drive overall accuracy disparity, but also certain additional factors, which render children with DLD less sensitive to case-(mis)match.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed at clarifying how certain aspects of Russian RC structure affect comprehension for TD children and their peers with DLD. Examining the pattern of performance of our participants on various RC types allowed us to identify three aspects of RC structure - a non-canonical word order, center-embedding, and case-mismatch – that engender extra cognitive effort during processing. Examining how these aspects of RC structure affect TD children allows us to clarify the role of working memory resources as opposed to non-resource-capacity factors in sentence processing. As we discussed in section 2, extra complexity triggered by the non-canonical word order (phrasal displacements) should result in lower accuracy of object-gap sentences (in both center-embedded and right-branching conditions) relative to subject-gap sentences. This greater difficulty cannot be attributed to additional memory demands, as these sentences contain no intervening NP between the head of the RC and the gap, and the verb immediately follows the relative pronoun. On the other hand, an effect of greater memory load should be observed as a lower accuracy of center-embedded sentences (both subject- and object-gap) relative to right branching sentences. A cognitive cost of case matching (Sauerland & Gibson, 1998), i.e., processing a sequence of two NPs (the RC head and the relative pronoun) with non-parallel functions and, consequently, non-congruent morphological case, should lead to greater difficulty of RCs with non-parallel cases (object-gap CE and subject-gap RB) relative to conditions with parallel cases.

Our analytical approach allows us to isolate each effect and entertain the possibility that processing of RC sentences is affected by multiple factors simultaneously, as there is no logical necessity for only one complexity factor to be at play. Our analyses revealed that the children indeed exhibited all three effects – Embedding, Gap, and Case (while our off-line comprehension task was not sensitive enough to assess the effects of various aspects of RC structure on adult performance).

With respect to the effect of gap, our experimental design does not allow us to determine more precisely what underlies the greater complexity of the object-gap word order because object-gap RCs are less frequent than subject-gap based on a Russian corpus study (Levy et al. 2013), involve greater representational complexity measured by the depth of gap embedding (O’Grady, 1997), and, because of phrasal displacement, require relying on morphological cues for identifying syntactic and semantic relations to a greater extent than subject-gap RCs (Caplan & Waters, 1999). However, it is reasonable to expect that any of these properties may drive the gap effect. The importance of working memory resources for RC comprehension is underscored by the greater complexity of center-embedded RCs relative to RB RCs. Greater processing complexity of case-mismatch RCs is likely a morphological processing effect; i.e., an anti-priming effect of incongruent case marking. However, it is also possible that case-mismatch, overlapping with non-parallel function, involves greater working memory costs, as previously suggested by King & Just (1991).

Given that we detected significant effects of all three factors of interest, syntactic complexity does not seem reducible to just one mechanism, but involves multiple sources. This finding is in keeping with other studies of RC comprehension in children from morphologically rich languages, such as Hungarian (Kas & Lukács, 2012; Macwhinney, & Pleh, 1988). What our study adds to this literature is the finding that sources of syntactic complexity are likely related to working memory capacity and at the same time directly linked to grammatical processing unrelated to memory capacity.

In support of the importance of working memory in sentence comprehension, we found that the group-by-experimental effect interactions we observed when comparing the performance of TD children and adults all lost significance after controlling for working memory, suggesting that differences in memory capacity were largely responsible for the qualitatively different performance of children relative to adults. Thus, our results underscore the important role of working memory maturation in acquiring adult-level facility in sentence processing. This seems to extend to the structural aspects that should not depend on working memory capacity according to certain theoretical accounts, such as object-gap in RCs with the “local” (in the sense of the locality theory of Gibson, 2000) OVS word order. Thus, it appears that even if the interpretation of displaced constituents gives rise to syntactic complexity effects independently from imposing extra demands on working memory, this does not exclude the influence of working memory on this aspect of sentence interpretation.

There may be an additional source of overall processing complexity related to working memory resources present in all of our stimuli, namely similarity-based interference (Gordon, Hendrick, & Jonson, 2001). Given the semantic similarity of the three NPs in all of our stimuli, this is likely a factor that affected the overall level of accuracy in all of our groups to the extent commensurate with their working memory resource capacity. Similarity-based interference, however, cannot explain the full pattern of results we obtained, as sentences of all conditions were equally complex with respect to semantic similarity of the NPs in each sentence.

Despite of the important role of working memory in RC comprehension our study confirmed, we also found that it cannot be the whole story. Even after controlling for working memory, the effect of group remained significant, with TD children’s performance being significantly less accurate than that of adults. This suggests that increases in working memory are not sufficient for reaching adult-like level of RC processing. A likely source of overall lower performance in children is the speed, efficiency and automaticity of the sentence processing system. As is attested in the literature, during processing, adults efficiently integrate incoming constituents into the representation, as it gets constructed, concurrently accessing various sources of information and integrating both bottom-up and top-down information (Altmann & Mirkovic, 2009; Tanenhaus & Brown-Schmidt, 2008). In contrast, children have more difficulty than adults accessing different knowledge sources, i.e., have a weaker ability to use top-down information, are less efficient in evaluating different types of information in parallel, have a slower speed of lexical access and retrieval. All of these factors may interfere with children’s ability to perform syntactic analysis in real time leading to relatively frequent misinterpretations (Clahsen & Felser, 2006).

Our second goal was to evaluate the syntactic, processing and morphological deficit views of DLD by comparing the effects of the complexity factors in question on the performance of the two groups of children – those with and without DLD. The significantly lower overall accuracy rate in the DLD group compared to the TD group we found could be fully explained by the group differences in working memory scores. This strongly suggests that working memory capacity must be part of the theory accounting for comprehension deficits of complex syntactic structures in DLD. However, as in the comparison between TD children and adults, we found that certain differences between children with and without DLD could not be easily explained by the differences in working memory. To clarify what factors may be involved, we will consider the specific predictions we made earlier and repeated below:

If a core deficit in DLD is related to processing non-canonical word orders (displaced constituents), or, more generally, representing long-distance dependencies, the DLD group should be disproportionately more error-prone on object-gap RCs, manifested as a Group-by-Gap interaction.

If the core problem in DLD is reduced working capacity, the DLD group should have disproportionate difficulty interpreting sentences with higher storage/integration costs and underperform on the CE conditions, manifested as a Group-by-Embedding interaction.

If children with DLD have special difficulties processing non-parallel function and/or a sequence of incongruently case marked NPs, we expect them to have extra difficulty with Case-mismatch sentences, manifested as a Group-by-Gap-by Embedding interaction.

First, we did not obtain a significant Group by Gap interaction. Thus, although we found clear evidence that both groups of children had substantially more difficulty with object-gap RCs compared to subject-gap RCs, we failed to observe a larger detrimental effect of object-gap on the DLD group. Thus, it appears that our data does not support the syntactic deficit view, attributing difficulties in comprehension of complex structures in children with DLD to a representational/computational deficit, such as difficulty representing syntactic movement (van der Lely, 1998), an inability to assign θ-roles through the trace to the moved element (Stavrakaki, 2001), or a general deficit in computing/representing complex syntactic dependencies (van der Lely, 2005). The lack of Gap by Group interaction also contradicts a scenario, in which children with DLD, to a greater extent than TD children, unable to cope with syntactic complexity of RCs, do not perform morphological analysis and a fully articulated syntactic parse and instead resort to a “rough-and ready” or shallow parse relying on a default heuristic (i.e., assigning the roles Agent-Theme to two successive arguments based on their linear order), a successful strategy in sentences with canonical word order, but a failing strategy when the word order is altered, and where one must rely on functional elements to deduce their grammatical and semantic roles (Caplan & Waters, 1999; Ferreira, 2003; Townsend & Bever, 2001). In the absence of a significant Gap-by-Group interaction, we have to conclude that children with DLD follow the same processing procedures as their TD counterparts when interpreting RCs type with a non-canonical word order.

Similarly, we did not find evidence that children with DLD are disproportionately affected by center-embedding, despite of the importance of working memory in explaining the overall differences between the two groups we found. This may be a consequence of a relatively weak effect of single center-embedding with no additional co-occurring complexity features, such as case-mismatch or object-gap. This would explain contradictory earlier findings with respect to single center-embedding, with some studies failing to find detrimental effects of single center-embedding on sentence comprehension (see de Villiers et al., 1979, for a review).

Finally, we found that controlling for working memory scores revealed different performance patterns of the two groups of children with respect to the Case effect. The TD group accuracy was significantly lower on the case-mismatching sentences relative to their case-matching counterparts, in concert with a German study with adults (Sauerland & Gibson, 1998). In a striking contrast, for the children with DLD, there was no comparable disparity between case-matching and case-mismatching conditions. This pattern of performance lends itself well to the account of DLD that considers acquisition and use of grammatical morphology to be a core DLD deficit, i.e., a weakness in extracting patterns and making generalizations, perhaps attributable to a deficit in the procedural memory system (Conti-Ramsden & Jones, 1997; Lum, Gelgic, & Conti-Ramsden, 2010; Ullman & Pierpont, 2005). If this is correct, children with DLD would have a less well-developed system of morphological categories or exponents and/or less well developed morphological analysis skills. This would interfere with processing complex structures in general, but also would render case-match less beneficial (or the complexity feature of case-mismatch less detrimental). Furthermore, as this phenomenon only became apparent after we controlled for working memory, we have to treat it as a syntactic processing phenomenon independent from children’s deficient working memory.

The latter finding is in keeping with the previous cross-linguistic research that showed that TD children actively use case markers as interpretive cues in RCs. Thus, in a study of German-speaking children, Arosio and colleagues (Arosio et al., 2012) compared the effect of a disambiguating case-marked DP with that of the number-marked DP and the verb agreement in Object-gap examples like 14–15 below. In both of these examples, the temporal ambiguity extends to the relative pronoun. In (16), it is disambiguated by the case marking on the determiner, while in (15) by the verb agreement at the end of the sentence. Arosio et al. reported that children’s accuracy on Object-gap RCs disambiguated by case was significantly higher than on sentences in which the disambiguation was on the verb at the end of the sentence - above chance (albeit still relatively low at 59%) versus a chance-level performance respectively.

| (15) | Die Frau die die Kinder gesehen haben. the woman-SG who the children-PL seen have-PL “The woman who the children have seen.” |

| (16) | Die Frau, die der Clown gesehen hat the woman who the-NOM clown seen has “The woman who the clown has seen.” |

Our results confirm the role of morphological processing in RC comprehension in keeping with Arosio and colleagues’ results, as we also found an effect of case marking, albeit with a twist. While we did not contrast Case effect with another morphological effect, by crossing the gap position with the embedding type, we were able to add a different dimension, namely case-match/mismatch in fully disambiguated sentences. We found that the mismatch adds complexity for TD children, but this complexity factor was not significant for our DLD group. Given that the latter had a documented difficulty with morphosyntactic processing (anonymous), the lack of the Case mismatch effect has important implications for understanding the nature of comprehension difficulties in children with DLD. It shows that a key deficit in children with DLD lies not with syntactic computation, but with morphological processing, in addition to their deficits in working memory resources.

Our study had several limitations. One major limitation was a wide age-range of children in our sample. This was a consequence of working with a unique small population (anonymous) and having to recruit children with a documented DLD from this population. Despite this limitation, we believe that children in our sample provide a unique opportunity not only to study the manifestations of DLD in a rarely studied in clinical literature language, but also allow us to avoid difficulties that come from studying clinical samples from typically highly heterogeneous clinically referred populations of children with DLD used in the majority of DLD/SLI studies.

A second limitation was the use of an off-line comprehension measure rather than a more sensitive, time-course measure of sentence processing allowing a more fine-grained analysis of the effects of each complexity factor. However, our method, which had the advantage of technical simplicity, important for a study conducted in a remote rural setting, yielded interesting observations. Third, as revealed by the floor-level performance of both groups of children on the most complex condition, the linguistic materials we used in our comprehension task were exceedingly challenging for them. Perhaps, sentences with two, rather than three, NPs would have allowed us to get additional qualitative differences in performance of the two groups of children. Finally, the working memory measure we used (Digit Span), one of the most frequently used in research with children, may not be tapping into all relevant aspects of the construct of verbal working memory. It, however, has the advantage of being easily adapted for use with speakers of other languages.

6. Conclusions

Our results support the view that maintains that language comprehension is directly constrained by working memory capacity and that variation in this capacity is a major source of variance observed in language comprehension. We found that working memory capacity is an important source of group differences in RC comprehension accuracy between adults and TD children, as well as between children with and with DLD. We also found that working memory maturation does not fully account for the observed quantitative differences in RC comprehension accuracy between adults and TD children. Thus, a complete account of RC comprehension in typical development must also include additional explanations, such as children’s still maturing capacity for efficient deployment of linguistic knowledge in real time. Secondly, our results support a multifactorial view of DLD, as a disorder characterized by both limitations in working memory and a deficit traceable to using morphological markers as processing cues, two independent sources of difficulties with comprehension of complex structures, such as RCs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01 DC007665 to Elena L. Grigorenko. Grantees undertaking such projects are encouraged to express freely their professional judgment. This article, therefore, does not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the National Institutes of Health, and no official endorsement should be inferred. We thank Roman Koposov from Northern State Medical Academy (Arkhangelsk, Russia) for his help with data collection, and Jodi Reich from Yale University for help with the stimuli preparation. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions to this research by the late Dr. Maria Babyonyshev.

FUNDING: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, R01 DC007665

Appendix. Sample Items

Item 1.