Abstract

Dual-targeted imaging agents have shown improved targeting efficiencies in comparison to single-targeted entities. The purpose of this study was to quantitatively assess the tumor accumulation of a dual-labeled heterobifunctional imaging agent, targeting two overexpressed biomarkers in pancreatic cancer, using positron emission tomography (PET) and near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging modalities. A bispecific immunoconjugate (heterodimer) of CD105 and tissue factor (TF) Fab′ antibody fragments was developed using click chemistry. The heterodimer was dual-labeled with a radionuclide (64Cu) and fluorescent dye. PET/NIRF imaging and biodistribution studies were performed in four-to-five week old nude athymic mice bearing BxPC-3 (CD105/TF+/+) or PANC-1 (CD105/TF−/−) tumors xenografts. A blocking study was conducted to investigate the specificity of the tracer. Ex vivo tissue staining was performed to compare TF/CD105 expression in tissues with PET tracer uptake to validate in vivo results. PET imaging of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 in BxPC-3 tumor xenografts revealed enhanced tumor uptake (21.0 ± 3.4 %ID/g; n = 4) compared to the homodimer of TRC-105 (9.6 ± 2.0 %ID/g; n=4; p < 0.01) and ALT-836 (7.6 ± 3.7 %ID/g; n=4; p < 0.01) at 24 h post-injection. Blocking studies revealed that tracer uptake in BxPC-3 tumors could be decreased by four-fold with TF blocking and two-fold with CD105 blocking. In the negative model (PANC-1), heterodimer uptake was significantly lower than that found in the BxPC-3 model (3.5 ± 1.1 %ID/g; n=4; p < 0.01). The specificity was confirmed by the successful blocking of CD105 or TF, which demonstrated the dual targeting with 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 provided an improvement in overall tumor accumulation. Also, fluorescence imaging validated the PET imaging, allowing for clear delineation of the xenograft tumors. Dual-labeled heterodimeric imaging agents, like 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, may increase the overall tumor accumulation in comparison to single-targeted homodimers, leading to improved imaging of cancer and other related diseases.

Keywords: positron emission tomography (PET), copper-64 (64Cu), heterodimer, tissue factor, CD105, dual-targeting

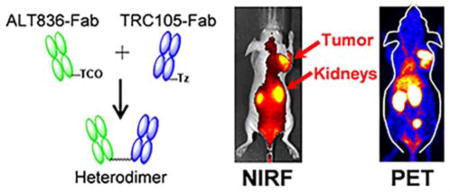

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Despite significant advancements in surgical intervention, pharmacological therapy, and radiotherapy, pancreatic cancer remains a highly lethal disease accounting for more than 250,000 deaths worldwide each year.1 To improve the dismal survival rates associated with pancreatic cancer, significant research efforts have been devoted to the development of new imaging tracers for cancer imaging and improved treatment options.2, 3 Currently, multisection computed tomography (CT) is utilized for imaging patients with suspected pancreatic cancer due to its optimal enhancement, high spatial resolution, speed, and wide availability. Molecular imaging modalities like 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are utilized in patients with equivocal findings by CT or ultrasound for detection, staging, and monitoring the progression and regression of the disease. While 18FDG-PET imaging has improved the detection of pancreatic malignancies, the tracer fails to reliably detect small primary lesions of less than 6 mm or liver metastases of less than 1 cm. Also, the tracer can accumulate in nonmalignant tissues, such as inflammatory tissues.4, 5

Dual-modality imaging has shown improvements over single modality imaging, yet few tracers are available for these studies. For example, the high spatial resolution of optical imaging can compensate for the low spatial resolution of PET imaging.6, 7 Also, optical imaging enables real-time detection of malignancies and permits imaging-guided resection of diseased tissue in an intraoperative setting.8 Dual-labeled imaging agents combining radioactive and fluorescent contrast entities into a single tracer may improve the diagnosis, staging, operational guidance, and therapeutic monitoring of disease.9 Development of dual-modality imaging agents with high targeting specificity will allow for researchers to combine the advantages of PET and optical imaging to improve pancreatic cancer patient outcomes in the future. Near-infrared optical imaging has become readily available for clinical studies due to the advent of flexible confocal laser microscopes for fluorescence laparoscopy, which when used with highly effective imaging agents, allows for surgical-guided excision of pancreatic tumors.10

Owing to their particular tumor-homing and high antigen specificity properties, monoclonal antibodies and their fragments have been broadly exploited as an imaging tool for detection of cancer.11 Bispecific antibody fragments for the simultaneous targeting of two different antigens have been shown to enhance tumor uptake.12 For example, Razumienko et al. evaluated a 177Lu-labeled bispecific heterodimer that binds to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on breast cancer cells. The heterodimer was shown to accumulate two-fold higher in tumor-bearing mice than the corresponding homodimers.13 Later, Kwon et al. evaluated the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and tumor imaging of the bispecific HER2 and EGFR heterodimer in tumor-bearing mice.14 Previously, the same group investigated another heterodimer targeting both HER2 and HER3 and discovered similar findings.15 While heterobifunctional tracers can be designed using various methods, bioorthogonal click chemistry provides a reliable, rapid, highly selective, and efficecient strategy to obtain high yields and minimal purification.16, 17 In reference to click chemistry, the high specificity of the TCO:Tz reaction yeilds the heterodimer (given Fab:TCO and Fab:Tz molar ratios of >1) that may be readily separable from the two Fab′ fragments. Moreover, click chemistry reactive moieties do not hydrolyze or participate in side reactions, which is of great advantage to obtain highly stable product with excellent yields. 18, 19

CD105 and TF are two biomarkers known to be upregulated in pancreatic cancer. CD105, also known as endoglin, is a cell surface glycoprotein expressed on endothelial cells and its overexpression in cancer has been linked to angiogenesis, metastasis, and cancer progression.20 In pancreatic cancer, CD105 expression is localized to the endothelial cells of small capillary-like vessels and lymphatic endothelial cells.21–23 TF is a transmemebrane glycoprotein known to initiate the coagulation cascade, yet the frequent upregulation of the receptor on cancer cells contributes to several pathologic processes, including angiogenesis, thrombosis, metastasis, and tumor growth in pancreatic cancer.24, 25 TRC105 is a human/murine chimeric IgG1κ monoclonal antibody targeting CD105. ALT-836 is a human-murine chimeric monoclonal antibody (IgG4) that targetsTF. In this study, we constructed a heterodimer from the Fab′ fragments of TRC105 and ALT-836 through click chemistry. This agent was radiolabeled with 64Cu and injected into pancreatic cancer mouse models to quantitatively assess the tumor accumulation of a dual-labeled heterobifunctional imaging agent, targeting two overexpressed biomarkers in pancreatic cancer, using positron emission tomography (PET) and near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging modalities.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis and Purification of Heterodimer and Homodimers

ALT836 is a chimeric IgG4 monoclonal antibody developed by Altor Bioscience Corporation (Miramar, FL, USA) and TRC105 is chimeric IgG1κ monoclonal antibody developed by TRACON Pharmaceuticals (San Diego, CA, USA). As shown in Fig. 1, ALT836 and TRC105 were digested in immobilized papain, purified by HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-100 HR and protein A column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), and respectively mixed with trans-Cyclooctene (TCO)-PEG4-NHS ester and tetrazine (Tz)-PEG5-NHS ester (Click Chemistry Tools, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 8.5 for 2 h incubation at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were individually passed through PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) to collect the ALT836-Fab and TRC105-Fab. Collected Fab′ units were mixed at an equimolar ratio in PBS buffer and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Heterodimers were separated by gel filtration on a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-100 HR. ALT836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2 homodimers were generated using the same procedure.

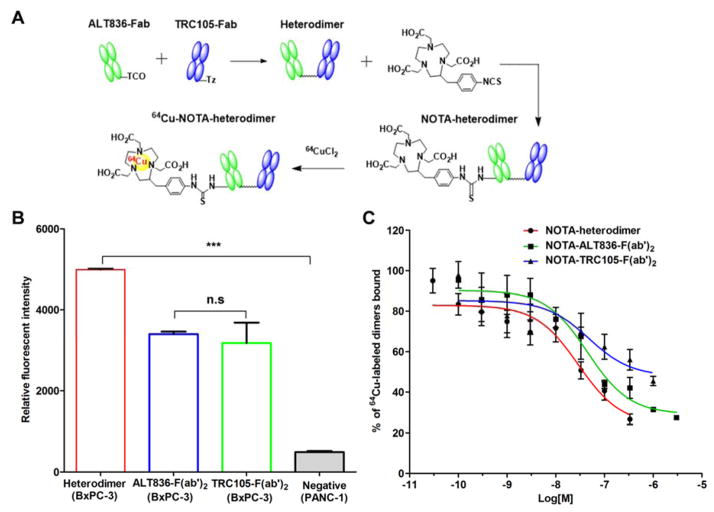

Figure 1.

Synthesis and in vitro characterization of 64Cu-labeled heterodimer and homodimers of ALT836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2. (A) Schematic representation of the synthesis of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer. (B) Flow cytometry analysis in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells after 30 min incubation of FITC-labeled heterodimer and homodimer conjugates. (C) Competitive binding assay comparing the binding affinities of NOTA-heterodimer, NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2 and NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2 in BXPC-3 cells.

Fluorescent and 64Cu-Labeling of Heterodimer

64Cu was produced in a CTI RDS 112 cyclotron via 64Ni(p,n)64Cu reaction using an established protocol.12 Conjugation of the chelator p-SCN-Bn-NOTA (Macrocyclic, Dallas, Texas, USA) was performed at pH 9.0 with a reaction ratio of ten p-SCN-Bn-NOTA per heterodimer. NOTA-heterodimers were purified using PD-10 columns with PBS and conjugated with the zwitterionic fluorophore ZW800-1 (ZW800) (λex=773 nm, λem=790 nm; Curadel ResVet Imaging, Marlborough, Massacheuttes, USA) in a 1:2 molar ratio through the primary amines of lysine amino acid residues. Next, 50–100 μg of NOTA-heterodimers or NOTA-heterodimers-ZW800 with 74–148 MBq (2–4 mCi) of 64CuCl2 in 300 μL of sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5), at 37 °C for 30 min under constant agitation (400 rpm) and purified via PD-10 columns.

Cell Lines and Animal Model

All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The human pancreatic cancer cell lines, BxPC-3 and PANC-1, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia, USA) and cultured according to the supplier’s protocol using Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 for BxPC-3 and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) for PANC-1. The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin, both obtained from Gibco of ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). A 1:1 solution of 5 × 106 tumor cells and Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) was subcutaneously injected into the front flank of four-to-five week old female athymic nude mice. When the tumor diameters reached 5–8 mm, mice were used for experiments.

Flow Cytometry

TF and CD105 binding affinity and specificity of heterodimers were evaluated in vitro by flow cytometry in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 cells. Briefly, cells were harvested, suspended in PBS supplemented with 2% BSA at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL, and incubated with 50 nM fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dimer conjugates for 30 min at room temperature. The FITC-labeled dimers were synthesized by mixing FITC with the dimer at a molar concentration of 20:1 in a carbonate buffer (pH 8.5) for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation, the FITC-labeled dimers were purified via PD-10 columns. Samples were washed and analyzed with the FACSCalibur 4-color analysis cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Competitive Cell Binding Assay

BxPC-3 cells (5 × 105) were seeded into each well of 96-well filter plates. Next, 20,000 cpm of 64Cu-labeled heterodimer, ALT836-F(ab′)2, or TRC105-F(ab′)2 were separately added into the wells. Next, increasing concentrations, in the range of 30 pM to 3 μM, of NOTA-heterodimer, NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2, or NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2 was added to the wells and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Plates were then rinsed with cold 0.1% BSA in PBS, dried, and PVDF filters were obtained, and the activity was counted using an automated γ-counter. Competitive binding curves were plotted, and IC50 calculated using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA). All data points were collected in triplicate.

PET/NIRF Imaging and Biodistribution Studies

PET scans were performed using an Inveon microPET/microCT rodent scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA). BxPC-3 or PANC-1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with 5–10 MBq (150 – 300 μCi) of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, or 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800, and sequential static PET scans with 20 million coincidence events were acquired at 3, 12, and 24 h post-injection. NIRF imaging of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 was performed immediately after each PET scan. After the last PET scan at 24 h post-injection, mice were euthanized, and the radioactivity was measured in the blood, tumors, and major organs/tissues using an automated γ-counter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Tracer uptake was reported as percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g; mean ± SD). For blocking studies, BxPC-3 tumor-bearing mice were injected with 40 mg/kg of intact ALT836 or TRC105 at 12 h before administration of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800.

Histology

Frozen tissue sections (5 μm) were fixed with cold acetone for 10 min and allowed to air dry. Sections were blocked with 10% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature and incubated with dual NOTA and ZW800-conjugated heterodimer or homodimers overnight at 4ºC. Next, sections were stained with Alexa Fluor488-labeled goat anti-human IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 4ºC for 2 h. Rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody and Cy3-labeled donkey anti-rat IgG (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used for CD31 staining (red). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used to stain cell nuclei, and images were acquired using the Nikon A1R confocal laser microscope system (Melville, NY, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Means were compared using the unpaired Student’s t-test with p values of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Evaluation of the Heterodimer Bispecificity

The ALT836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2 homodimers and the heterodimer, which combined a single Fab′ of both ALT836 and TRC105, were synthesized using click chemistry (Fig. 1). Analysis of flow cytometry data revealed a stronger binding capacity of the heterodimer to BxPC-3 cells (TF/CD105+/+) compared to ALT836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2 homodimers (Fig. 1B). Also, the fluorescence signal of the heterodimer in BxPC-3 cells (TF/CD105+/+) was significantly stronger than that of PANC-1 cells (TF/CD105−/−), which further confirmed the specificity of the heterodimer.26 Together, these results prove that dual targeting of TF and CD105 exhibited an improved effect. Next, the binding affinity of the heterodimer was compared to the homodimers using a competitive binding assay (Fig. 1C). The binding isotherm showed that the IC50 values of 64Cu-labeled heterodimer, ALT-836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2 were 29.17 ± 1.51, 44.9 ± 1.0, and 47.71 ± 2.53 nM, respectively.

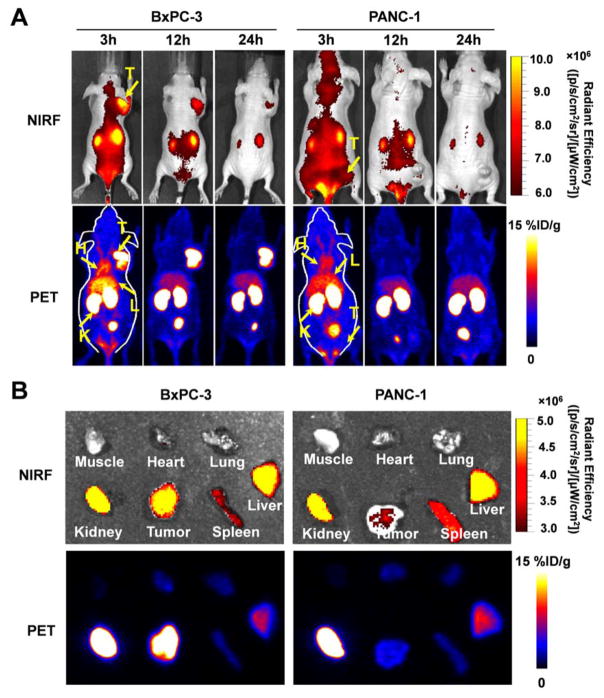

PET Imaging of Heterodimer Reveals Enhanced Targeting Capabilities

To evaluate the dual targeting capacity and combined specificity of the heterodimer in vivo, ALT836-F(ab′)2 and TRC105-F(ab′)2 homodimers were synthesized as controls and dual labeled with 64Cu and ZW800 (Supplemental Fig. S1). After radiolabeling with 64Cu, 200–300 μCi of either 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, or 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 were administered into BxPC-3-derived tumor-bearing mice and imaged at 3, 12, and 24 h post-injection. For comparison, 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 was also injected into mice bearing PANC-1 tumors. Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) images of BxPC-3 tumor-bearing mice revealed rapid tumor accumulation of all three tracers that allowed for the clear delineation of tumor xenografts. 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 presented significantly higher tumor accumulation (21.0 ± 3.4 %ID/g at 24 h post-injection; n=4) than the CD105-targeted homodimer (9.6 ± 2.0 %ID/g; n=4, P<0.01) or TF-targeted homodimer (7.6 ± 3.7 %ID/g; n=4, P<0.01) at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 2, Table 1).

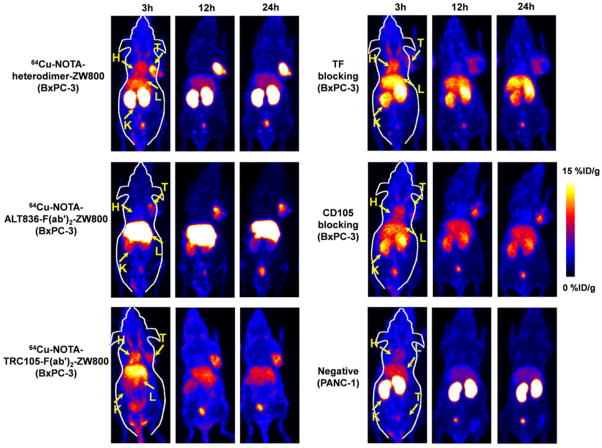

Figure 2.

PET imaging of CD105 and tissue factor (TF) expression using dual-labeled heterodimer and homodimers in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 tumor xenograft-bearing mice. Maximum intensity projections (MIPs) of mice with BxPC-3 tumors with 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 at 3, 12 and 24 h post-injection (n≥3). Both TF and CD105 blocking resulted in decreased tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 in BxPC-3 tumors. MIPs of mice bearing PANC-1 tumors with 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 at 3, 12 and 24 h post-injection (n≥3). H=heart, K=kidney, L=liver, T=tumor

Table 1.

Quantitative PET data of tracer uptakes in BxPC-3 or PANC-1 bearing nude mice

| Imaging group | Tissue | Time post-injection of the tracer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 3 h | 12 h | 24 h | ||

| 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 (Positive; n=4) | BxPC-3 | 19.4 ± 3.4 | 22.1 ± 2.3 | 21.0 ± 3.4 |

| Blood | 11.8 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | |

| Liver | 14.6 ± 1.2 | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 7.9 ± 0.3 | |

| Kidney | 27.8 ± 2.9 | 28.9 ± 1.0 | 22.3 ± 1.6 | |

| Muscle | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | |

|

| ||||

| 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800 (n=4) | BxPC-3 | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 7.5 ± 2.9 | 7.6 ± 3.7 |

| Blood | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Liver | 31.7 ± 3.3 | 22.8 ± 1.6 | 24.3 ± 2.2 | |

| Kidney | 10.3 ± 1.1 | 10.8 ± 3.4 | 7.4 ± 2.3 | |

| Muscle | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | |

|

| ||||

| 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 (n=4) | BxPC-3 | 7.6 ± 1.6 | 10.3 ± 1.9 | 9.6 ± 2.0 |

| Blood | 12.2 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | |

| Liver | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 10.6 ± 0.7 | |

| Kidney | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | |

| Muscle | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

|

| ||||

| 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 (Negative; n=3) | PANC-1 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 1.1 |

| Blood | 10.6 ± 2.5 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Liver | 13.0 ± 2.5 | 7.9 ± 1.4 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | |

| Kidney | 25.3 ± 4.3 | 29.9 ± 2.1 | 24.8 ± 1.2 | |

| Muscle | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | |

Values are reported as %ID/g (mean ± SD)

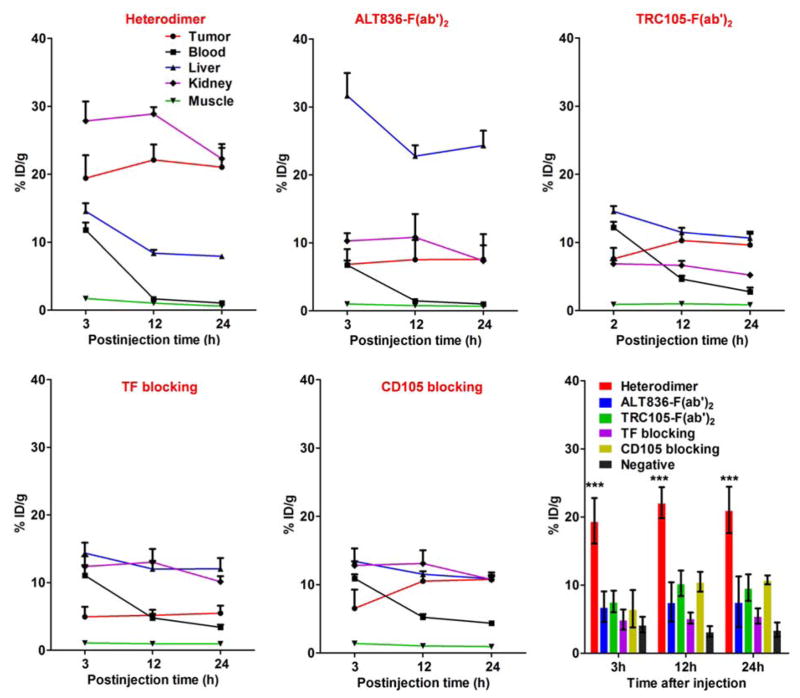

Region-of-interest (ROI) analyses of the images were performed for quantification of tracer uptake in BxPC-3 and PANC-1 tumors, as well as non-target tissues, including the blood pool, liver, kidney, and muscle. As clearly depicted in the PET images (Fig. 2), 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 displayed high tumor accumulation from early time points, with 18.4 ± 3.4 %ID/g at 3 h post-injection, which peaked (22.1 ± 2.3 %ID/g) at 12 h post-injection of the tracer (n=4). Interestingly, kidney uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800 and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 was lower than that of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, suggesting renal clearance as the major excretion pathway of the heterodimer (Fig. 3, Table 1). Liver uptake was comparable between 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800; however, two-fold higher values were registered for 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, indicating a more dominant hepatic clearance of the ALT836-F(ab′)2 homodimer (Table 1). A comparison of blood activity at the final imaging time point (24 h post-injection) revealed similar values for the heterodimer and each homodimer.

Figure 3.

Quantitative region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of in vivo imaging data. Time-activity curves of the PET signal in BxPC-3 tumor, blood, liver, kidney and muscle following intravenous administration of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800, and 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 after TF or CD105 blocking (n≥3). Comparison of tumor uptake in all groups and the negative control by quantitative analysis of the PET data (n≥3).

To demonstrate that 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 retained its specificity towards both TF and CD105 in vivo, a significant blocking dose (40 mg/kg) of intact ALT836 or TRC105 antibody was administered into mice 12 h before injection of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 to block the TF and CD105 receptors, respectively. 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 accumulation in BxPC-3 tumors was significantly decreased upon blocking of TF (5.5 ± 1.1 %ID/g; n=3) or CD105 (10.8 ± 0.7 %ID/g; n=3) at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 3, Table 2). Tracer uptake in all major organs was similar between 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 and 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 with TF or CD105 blockade, except for increased kidney signal. Low tracer uptake in PANC-1 tumors at the background level further confirmed the TF and CD105 dual-specificity of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Supplemental Fig. S2). These data suggest that dual targeting of TF and CD105 with a heterobifunctional tracer improved absolute tumor uptake and target-specificity while decreasing off-target accumulation in non-diseased tissues, as compared to homodimeric tracers.

Table 2.

Quantitative PET data of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 tracer uptakes after TF or CD105 blocking in BxPC-3-bearing nude mice

| Blocking group | Tissue | Time post-injection of the tracer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 3 h | 12 h | 24 h | ||

| TF blocking (n=3) | BxPC-3 | 4.9 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 1.1 |

| Blood | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | |

| Liver | 14.4 ± 1.5 | 12.0 ± 1.2 | 12.0 ± 1.6 | |

| Kidney | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 10.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Muscle | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | |

|

| ||||

| CD105 blocking (n=3) | BxPC-3 | 6.5 ± 2.7 | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 10.8 ± 0.7 |

| Blood | 10.9 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |

| Liver | 13.4 ± 1.9 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | |

| Kidney | 12.8 ± 0.6 | 13.1 ± 1.9 | 10.7 ± 0.5 | |

| Muscle | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | |

Values are reported as %ID/g (mean ± SD)

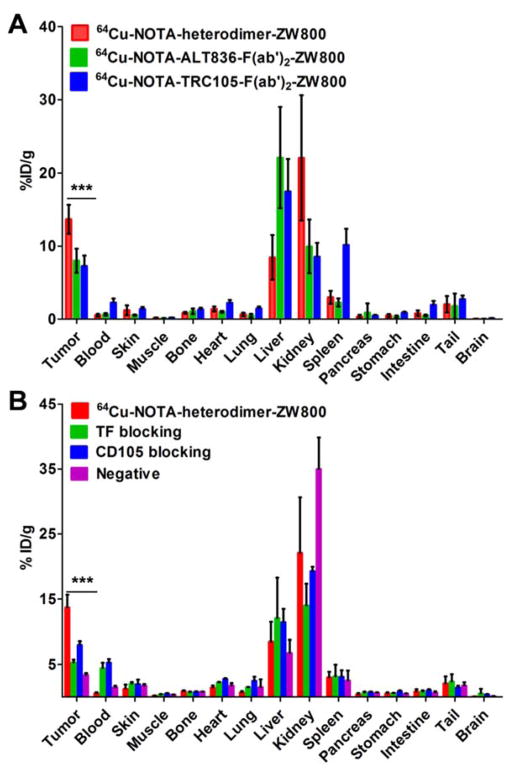

Ex Vivo Biodistribution Validates PET Findings

Ex vivo biodistribution and histology studies were executed after last PET scans at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 4A, Fig. 4B, Supplemental Table 1), which further validated the PET findings. An excellent tumor-to-muscle ratio of 90.8 ± 50.3 was calculated for 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 in the BxPC-3 tumor model at 24 h post-injection, due to the enhanced uptake of the heterodimer with low off-target signal (Supplemental Table 2). While the tumor-to-blood ratio was also high at 28.3 ± 12.6, this value was lower than the tumor-to-muscle ratio. From these data, the high tumor-to-muscle ratios were likely due to very low muscle uptake rather than high tumor uptake. Despite this fact, the tumor-to-muscle ratios of 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800 and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 were lower in comparison to the heterodimer at 69.5 ± 29.5 and 39.6 ± 28.1, respectively. The tumor-to-blood ratios for 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800 and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 were 11.9 ± 0.90 and 3.76 ± 28.1, respectively. In the negative tumor model (PANC-1), tumor-to-muscle and tumor-to-blood ratios of 9.74 ± 1.0 and 2.36 ± 0.61 were achieved, suggesting that tumors expressing low levels of CD105 and TF may still be imaged using this tracer (Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 4.

Ex vivo biodistribution validates the results of PET imaging. (A) Biodistribution of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, and 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 in BxPC-3 tumor-bearing mice after 24 h post-injection (n ≥ 3). (B) Biodistribution of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 after TF or CD105 blocking in BxPC-3 tumor-bearing mice and PANC-1 tumor-bearing mice (n ≥ 3).

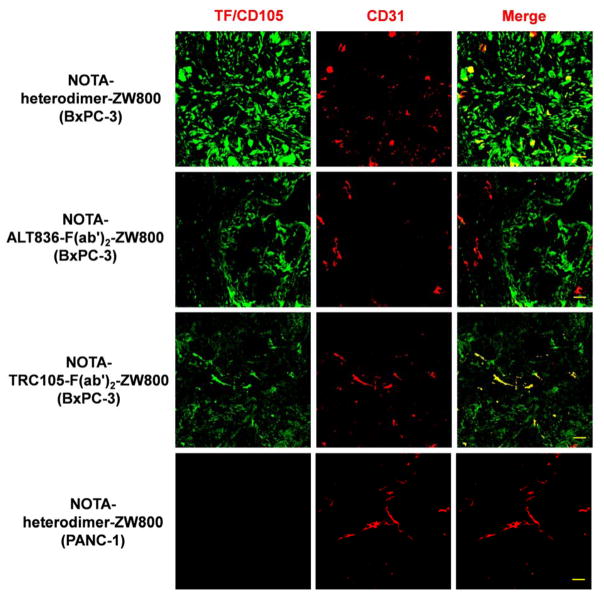

Immunofluorescence staining of resected BxPC-3 and PANC-1 tumor sections was performed to correlate PET-tracer uptake with in situ TF/CD105 expression (Fig. 5). 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 staining of the BxPC-3 tissue showed a strong fluorescent signal that was distributed on both tumor cells and tumor-associated vasculature, which was significantly higher than that in PANC-1 tissue sections. 64Cu-NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800 uptake was primarily on the membrane of TF-expressing BxPC-3 cells, whereas 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800 was found on both the cells and vasculature, which was confirmed by the colocalization of CD31. Together, these results confirm that 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 provides higher sensitivity and specificity for noninvasive imaging of TF/CD105-expressing malignancies.

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections validates the high expression of CD105 and tissue factor (TF) in a BxPC-3 xenograft model. Tissue sections were incubated with either NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, NOTA-ALT836-F(ab′)2-ZW800, or NOTA-TRC105-F(ab′)2-ZW800. Next, Alexa Fluor488-labeled anti-human IgG was used for TF/CD105 staining (green) of tumor sections. CD31 staining (red) was accomplished using a rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody with a Cy-3 labeled secondary antibody, while DAPI was used to stain cell nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 30 μm

Dual-Labeled Heterodimer for PET/NIRF Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer

To investigate the potential of dual-labeled 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 for sensitive detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in vivo, the dual-labeled tracer was separately administered into BxPC-3 and PANC-1 tumor-bearing mice, and PET/NIRF imaging was completed (Fig. 6). The mice underwent NIRF imaging of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 immediately after each PET scan. Similar to our findings from PET imaging, the signal detected in BxPC-3 tumors was much higher than that of PANC-1 tumors (Fig. 6A). Ex vivo imaging was employed to confirm the in vivo fluorescence imaging data at 24 h post-injection (Fig. 6B); however, tumors were clearly visualized at 3 h post-injection. While the highest fluorescence intensity of the heterodimer was detected at 3 h post-injection, the tumors could be better delineated at 12 h post-injection; thus, 3 to 12 h post-injection may be the best time-frame for intraoperative imaging. The NIRF and PET imaging of the excised organs and tissues revealed similar biodistribution profiles, further validating the biodistribution of the tracer and demonstrating the potential utilization of dual-labeled heterodimeric tracer for dual-modality imaging of pancreatic cancer.

Figure 6.

PET/NIRF imaging in mice bearing BxPC-3 or PANC-1 tumors with 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800. (A) Serial maximum intensity projections (MIPs) PET/NIRF images of mice bearing BxPC-3 or PANC-1 tumors at 3, 12 and 24 h following injection of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800. (B) Ex vivo PET/NIRF imaging of excised tumors, muscle, heart, lung, kidney, spleen and kidney from mice bearing BxPC-3 or PANC-1 tumors at 24 h post-injection. As shown, PET imaging provides better delineation of tumors due to its superior sensitivity, tissue penetration capabilities, and quantifiability, while optical imaging is hindered by its low spatial resolution and attenuation caused by overlying tissues.

DISCUSSION

Dual-modality PET/NIRF imaging provides a new perspective for in vivo imaging of pancreatic cancer. Antibodies are excellent candidates for creating high-affinity, dual-labeling imaging agents because of their high endogenous specificity.27 While therapeutic antibodies can actively accumulate in tumors, targeting a single biomarker often leads to suboptimal tumor accumulation due to the phenotypic heterogeneity and genetic complexity of cancer.28 Previously, it was shown that bispecific immunoconjugates displayed enhanced tumor uptake when compared to single targeted imaging agents, suggesting that heterodimeric constructs may be useful in both imaging and therapeutic studies.29 At this time, there is no report on dual-targeting antibody agents for multimodality imaging of cancer or related diseases.

Dual-modality imaging has become increasingly important in cancer diagnostics. As a newer imaging modality, optical imaging has become a key player in the real time imaging of diseases, while posing minimal health risks as it does not require patient exposure to radiation. In particular, the use of fluorescence-based laparoscopy for detection of pancreatic cancer has been assessed by several researchers using fluorescent-labeled proteins to aid in the surgical resection of malignant tissues.30–33 Most of these studies found that fluorescence laparoscopy provided a simple and real-time approach for imaging to localize primary and possibly metastatic pancreatic lesions.

In this study, we developed a dual receptor-targeting dual-modality PET and NIRF imaging probe, 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800, for imaging of pancreatic cancer. Noninvasive PET imaging with 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 showed significantly higher tumor uptake in comparison to either Fab fragment homodimer (Fig. 3), suggesting that dual-targeting provides an advantage in targeting tissues co-expressing TF and CD105. While both PET and NIRF imaging allowed for clear delineation of the tumor, it was interesting to note that NIRF signal was significantly weaker than that of PET (Fig. 6). This signal difference was attributed to the attenuation caused by overlying tissues, as ex vivo imaging showed comparable signal. Also, NIRF dyes easily lose fluorescence through in vivo degradation and efflux from the cells, whereas 64Cu has been shown to become trapped inside the cells once internalized.34, 35

While full antibodies are eliminated from the body through intracellular catabolism, antibody fragments are typically cleared through the hepatobiliary and renal pathways, which are largely dependent on their chemical structure, molecular size, and hydrophobicity of the protein.36 While PET imaging revealed that 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer was cleared predominantly by the liver,29 the 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 conjugate showed initial high liver and kidney signal, followed by gradual excretion through the kidneys (Fig. 2). The clearance pathway of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800 is consistent with a recent report on ZW800-labeled hyaluronate conjugated interferon-α (HA-IFNα),37 suggesting that ZW800 may be unstable when attached to the tracer. Since ZW800-1 had a net charge of zero and been reported to be cleared out through kidneys to bladder without nonspecific uptake in the main organs,38 the high kidney accumulation of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800-1 may challenge its potential clinical translation. However, the increased kidney uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-heterodimer-ZW800-1 was attributed to the expression of both CD105 and TF found in kidney tissues, which was reduced in the blocking groups (Fig. 3). Additionally, this also accounts for the increased liver signal in the blocking groups. Therefore, selection of optimal radionuclide/dye combinations is essential for improving the performance of dual-labeled probes for multimodality imaging, required. In future studies, several other NIRF dyes, including MHI-148, IR-783, and 800CW, displaying appropriate tumor-specific fluorescent properties may be investigated for improvement of multimodality imaging contrast and sensitivity.39 While the fusion of optical or photoacoustic imaging with other more quantitative imaging modalities can compensate for the low spatial resolution of PET or SPECT imaging, NIRF imaging remains limited by its low depth penetration, attenuation caused by overlapping tissues, and lack of quantitative methods for signal quantification.40

There have been numerous reports on the preclinical usefulness of antibodies and antibody fragments for immunoPET imaging using various radionuclides, including 18F, 64Cu, and 89Zr.11 Recently, Houghton et al. reported that immunoPET imaging of CA19.9 in pancreatic cancer using dual 89Zr and NIRF dye-labeled anti-CA19.9 antibody 5B1 via a site-specific labeling method.41 Blinatumomab, a bispecific T-cell engager antibody, was recently approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for therapeutic intervention in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which has inspired a renewed interest in the application of bispecific antibodies. 42

While this study was performed in a murine model of pancreatic cancer, there are several applications of this study that can be employed for future investigations. First, the biodistribution found in animals may be extrapolated to predict the overall distribution of the tracer in clinical patients. Also, this study provides insight into the improved effect of dual-targeting agents, which may lead to the developed of more heterodimeric imaging constructs with enhanced imaging capabilities in the future. In the future, bispecific imaging agents may assist researchers in evaluating complex biological interactions occurring in vivo by targeting two or more receptors at the same time, possibly bringing two proteins into close proximity with each to monitor and mediate these interactions. For example, a heterodimer targeting receptors on both tumor cells and T-cells may provide insight into tumor immunology. Additionally, previous studies have shown that antibody resistance may be reduced by using bispecific agents instead of monospecific antibodies.43–45 Lastly, the development of novel dual-labeled bispecific antibody agents for preclinical and clinical detection and characterization of malignancies may improve patient outcomes, allowing for more efficient imaging of tumors, which can improve intraoperative surgical guidance, provide insight into disease stage and progression, and improve patient stratification.

Herein, this study proved that dual-labeled heterodimeric imaging agents might show greater targeting capabilities than their corresponding homodimer constructs, suggesting that dual-targeting provides an advantage in targeting tissues expressing the antigens being targeted. Through dual PET and optical imaging, both TF and CD105 were simultaneously targeted using an antibody-based heterodimer radiolabeled with 64Cu. These data may assist researchers in the development of novel imaging agents that show enhanced targeting capabilities for cancer imaging in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365, 1R01EB021336, P30CA014520, T32CA009206), and the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE).

Footnotes

Notes:

Disclosure: Bai Liu and Hing C. Wong are employees of Altor BioScience Corporation and Charles P. Theuer is an employee of TRACON Pharmaceuticals Incorporation. The other authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information. Biodistribution values, a schematic representation of reaction, and time-activity curves.

References

- 1.Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 2. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamboni G, Hirabayashi K, Castelli P, Lennon AM. Precancerous Lesions of the Pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27(2):299–322. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heestand GM, Murphy JD, Lowy AM. Approach to Patients with Pancreatic Cancer without Detectable Metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(16):1770–1778. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frohlich A, Diederichs CG, Staib L, Vogel J, Beger HG, Reske SN. Detection of Liver Metastases from Pancreatic Cancer Using Fdg Pet. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(2):250–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoder H, Gonen M. Screening for Cancer with PET and PET/CT: Potential and Limitations. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(Suppl 1):4S–18S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gambhir SS. Molecular Imaging of Cancer with Positron Emission Tomography. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(9):683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallamini A, Zwarthoed C, Borra A. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in Oncology. Cancers (Basel) 2014;6(4):1821–1889. doi: 10.3390/cancers6041821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the Era of Molecular Oncology. Nature. 2008;452(7187):580–589. doi: 10.1038/nature06917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azhdarinia A, Ghosh P, Ghosh S, Wilganowski N, Sevick-Muraca EM. Dual-Labeling Strategies for Nuclear and Fluorescence Molecular Imaging: A Review and Analysis. Mol Imaging Biol. 2012;14(3):261–276. doi: 10.1007/s11307-011-0528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Burstin J, Eser S, Seidler B, Meining A, Bajbouj M, Mages J, Lang R, Kind AJ, Schnieke AE, Schmid RM, Schneider G, Saur D. Highly Sensitive Detection of Early-Stage Pancreatic Cancer by Multimodal Near-Infrared Molecular Imaging in Living Mice. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(9):2138–2147. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.England CG, Hernandez R, Eddine SB, Cai W. Molecular Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer with Antibodies. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(1):8–24. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo H, Hernandez R, Hong H, Graves SA, Yang Y, England CG, Theuer CP, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Noninvasive Brain Cancer Imaging with a Bispecific Antibody Fragment, Generated Via Click Chemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(41):12806–12811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509667112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razumienko EJ, Chen JC, Cai Z, Chan C, Reilly RM. Dual-Receptor-Targeted Radioimmunotherapy of Human Breast Cancer Xenografts in Athymic Mice Coexpressing HER2 and EGFR Using 177lu- or 111in-Labeled Bispecific Radioimmunoconjugates. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(3):444–452. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.162339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon LY, Scollard DA, Reilly RM. 64Cu-Labeled Trastuzumab Fab-Peg24-EGF Radioimmunoconjugates Bispecific for HER2 and EGFR: Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, and Tumor Imaging by PET in Comparison to Monospecific Agents. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(2):492–501. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razumienko EJ, Scollard DA, Reilly RM. Small-Animal SPECT/CT of Her2 and Her3 Expression in Tumor Xenografts in Athymic Mice Using Trastuzumab Fab-Heregulin Bispecific Radioimmunoconjugates. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(12):1943–1950. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.106906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hein CD, Liu XM, Wang D. Click Chemistry, a Powerful Tool for Pharmaceutical Sciences. Pharm Res. 2008;25(10):2216–2230. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9616-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon HY, Shin ML, Shim MK, Lee S, Na JH, Koo H, Lee H, Kim JH, Lee KY, Kim K, Kwon IC. Artificial Chemical Reporter Targeting Strategy Using Bioorthogonal Click Reaction for Improving Active Targeting Efficiency of Tumor. Mol Pharm. 2017 doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b01083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng D, Zeglis BM, Lewis JS, Anderson CJ. The Growing Impact of Bioorthogonal Click Chemistry on the Development of Radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(6):829–832. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.115550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wangler C, Schirrmacher R, Bartenstein P, Wangler B. Click-Chemistry Reactions in Radiopharmaceutical Chemistry: Fast & Easy Introduction of Radiolabels into Biomolecules for in Vivo Imaging. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(11):1092–1116. doi: 10.2174/092986710790820615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonsatti E, Altomonte M, Nicotra MR, Natali PG, Maio M. Endoglin (Cd105): A Powerful Therapeutic Target on Tumor-Associated Angiogenetic Blood Vessels. Oncogene. 2003;22(42):6557–6563. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshitomi H, Kobayashi S, Ohtsuka M, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Miyazaki M. Specific Expression of Endoglin (CD105) in Endothelial Cells of Intratumoral Blood and Lymphatic Vessels in Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37(3):275–281. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181690b97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SJ, Tilly H, Ward JH, Macarthur DC, Lowe J, Coyle B, Grundy RG. Cd105 (Endoglin) Exerts Prognostic Effects Via Its Role in the Microvascular Niche of Paediatric High Grade Glioma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(1):99–110. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0952-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H, Chen F, Zhang Y, Cai W. New Radiotracers for Imaging of Vascular Targets in Angiogenesis-Related Diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;76:2–20. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasthuri RS, Taubman MB, Mackman N. Role of Tissue Factor in Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(29):4834–4838. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas SL, Jesnowski R, Steiner M, Hummel F, Ringel J, Burstein C, Nizze H, Liebe S, Löhr JM. Expression of Tissue Factor in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Is Associated with Activation of Coagulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(30):4843–4849. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, Zhang Y, Nayak TR, Engle JW, Wong HC, Liu B, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Immuno-PET of Tissue Factor in Pancreatic Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(11):1748–1754. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olafsen T, Wu AM. Antibody Vectors for Imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2010;40(3):167–181. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo H, Hong H, Yang SP, Cai W. Design and Applications of Bispecific Heterodimers: Molecular Imaging and Beyond. Mol Pharm. 2014;11(6):1750–1761. doi: 10.1021/mp500115x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo H, England CG, Shi S, Graves SA, Hernandez R, Liu B, Theuer CP, Wong HC, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Dual Targeting of Tissue Factor and CD105 for Preclinical PET Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3821–3830. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran Cao HS, Kaushal S, Menen RS, Metildi CA, Lee C, Snyder CS, Talamini MA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Submillimeter-Resolution Fluorescence Laparoscopy of Pancreatic Cancer in a Carcinomatosis Mouse Model Visualizes Metastases Not Seen with Standard Laparoscopy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21(6):485–489. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran Cao HS, Kaushal S, Lee C, Snyder CS, Thompson KJ, Horgan S, Talamini MA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorescence Laparoscopy Imaging of Pancreatic Tumor Progression in an Orthotopic Mouse Model. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(1):48–54. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metildi CA, Kaushal S, Lee C, Hardamon CR, Snyder CS, Luiken GA, Talamini MA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. An Led Light Source and Novel Fluorophore Combinations Improve Fluorescence Laparoscopic Detection of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer in Orthotopic Mouse Models. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214(6):997–1007. e1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouvet M, Wang J, Nardin SR, Nassirpour R, Yang M, Baranov E, Jiang P, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM. Real-Time Optical Imaging of Primary Tumor Growth and Multiple Metastatic Events in a Pancreatic Cancer Orthotopic Model. Cancer Res. 2002;62(5):1534–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Progatzky F, Dallman MJ, Lo Celso C. From Seeing to Believing: Labelling Strategies for in Vivo Cell-Tracking Experiments. Interface Focus. 2013;3(3):20130001. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y, Baidoo KE, Brechbiel MW. Mapping Biological Behaviors by Application of Longer-Lived Positron Emitting Radionuclides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(8):1098–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal Antibody Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(5):548–558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim KS, Hyun H, Yang JA, Lee MY, Kim H, Yun SH, Choi HS, Hahn SK. Bioimaging of Hyaluronate-Interferon Alpha Conjugates Using a Non-Interfering Zwitterionic Fluorophore. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16(9):3054–3061. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi HS, Nasr K, Alyabyev S, Feith D, Lee JH, Kim SH, Ashitate Y, Hyun H, Patonay G, Strekowski L, Henary M, Frangioni JV. Synthesis and in Vivo Fate of Zwitterionic near-Infrared Fluorophores. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(28):6258–6263. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Shi C, Tong R, Qian W, Zhau HE, Wang R, Zhu G, Cheng J, Yang VW, Cheng T, Henary M, Strekowski L, Chung LW. Near Ir Heptamethine Cyanine Dye-Mediated Cancer Imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(10):2833–2844. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herranz M, Ruibal A. Optical Imaging in Breast Cancer Diagnosis: The Next Evolution. J Oncol. 2012;2012:863747. doi: 10.1155/2012/863747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houghton JL, Zeglis BM, Abdel-Atti D, Aggeler R, Sawada R, Agnew BJ, Scholz WW, Lewis JS. Site-Specifically Labeled Ca19.9-Targeted Immunoconjugates for the PET, NIRF, and Multimodal PET/NIRF Imaging of Pancreatic Cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(52):15850–15855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506542112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheridan C. Amgen’s Bispecific Antibody Puffs across Finish Line. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):219–221. doi: 10.1038/nbt0315-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banta S, Dooley K, Shur O. Replacing Antibodies: Engineering New Binding Proteins. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2013;15:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071812-152412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cochran JR. Engineered Proteins Pull Double Duty. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(17):17ps15. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JM, Lee SH, Hwang JW, Oh SJ, Kim B, Jung S, Shim SH, Lin PW, Lee SB, Cho MY, Koh YJ, Kim SY, Ahn S, Lee J, Kim KM, Cheong KH, Choi J, Kim KA. Novel Strategy for a Bispecific Antibody: Induction of Dual Target Internalization and Degradation. Oncogene. 2016;35(34):4437–4446. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.