Abstract

Obstetric traumatic separation of the distal humeral epiphysis is a very uncommon injury, which presents a diagnostic challenge. These case serials reviewed the functional outcomes of 5 patients who had sustained a fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis at birth. The diagnosis was made at a mean time of 40.8 h after delivery. All the patients were treated with gentle close manipulation, reduction under fluoroscopy and above-elbow cast application. After discharge, the patients were followed up for a mean of 30 months. Clinico-radiological results were excellent in four patients. One case necessitated closed reduction and percutaneous K-wire fixation at one week follow-up due to failed reduction. Cubitusvarus deformity was the only complication noted in 1 case. Good functional outcome can be expected in newborns with fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis wherein the physis is anatomically reduced.

Keywords: Infant, newborn; Humerus; Separation of epiphysis

Introduction

Obstetric traumatic separation of the distal humeral epiphysis is a rare injury that follows a traumatic delivery, often secondary to an abnormal presentation.1, 2 In a historical review of 30 years of experience, Madsen3 documented only one case of distal humeral epiphysis separation in 105,119 neonates. In the literature there is only sporadic cases or small case series reported.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 This lesion may be easily missed at birth, due to clinical and radiographic difficulty in diagnosis.13 From a clinical point of view, swelling, instability and limited range of motion (ROM) at the elbow are signs suggestive of fracture separation, however, these signs do not allow a definitive differential diagnosis with elbow dislocation. Moreover, when pseudoparalysis of the upper limb is present, it may justify the suspicion of an obstetric brachial plexus injury or other obstetric skeletal injuries.

Plain radiographs are difficult to interpret because the epiphyses of the elbow joint are unossified at birth.14 For these reasons, to confirm the diagnosis, many authors have suggested further investigations, such as sonography,5, 6, 7 MRI15, 16 and arthrography.17, 18 Till date the management of this lesion is not yet well established though most authors agree that the outcomes are satisfactory.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

In this paper we report our experience and treatment management concerning 5 cases of newborns who sustained a distal separation of epiphysis of the humerus at birth. Informed consent has been requested to the parents of the children involved in this case series.

Cases report

We present a series of 5 male neonates with traumatic separation of epiphysis of the distal humerus sustained at birth in two different Paediatric Orthopaedic Units. The collected clinical information included days at presentation after birth, type of delivery, affected side, type of injury and treatment. The clinical and radiographic outcomes were retrospectively analysed (Table 1). No comorbidities were reported in any of them. The vertex position of the fetus was confirmed by a pre-delivery ultrasonography. Four in five of the patients experienced vaginal delivery with cephalic presentation; while the other one was a premature neonate (24 weeks) born from a caesarean section with a low weight.

Table 1.

Data of patients with features and characteristics of fracture and treatment.

| Case | Side | Delivery and birth weight (g) | Initial diagnosis | Age at diagnosis (h) | Imaging | Treatment | Callus formation (days) | Follow-up (month) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L | VD/3125 | Elbow fracture | 72 | XR | Cast with closed reduction | 13 | 60 | Complete ROM |

| 2 | R | VD/2150 | Elbow fracture | 12 | XR, US | Cast with closed reduction/K-wire fixation | 15 | 15 | Complete ROM |

| 3 | R | VD/3460 | Elbow fracture | 48 | XR | Cast with closed reduction | 14 | 27 | Complete ROM |

| 4 | R | CS/700 | Elbow fracture | 48 | XR, US | Cast with closed reduction | 16 | 36 | Complete ROM |

| 5 | R | VD in water/2425 | Elbow fracture | 24 | XR | Cast with closed reduction | 18 | 12 | 5° of cubitus varus |

Note: All the patients were male gender. L = left, R = right, VD = vaginal delivery, CS = cesarean section, XR = plane radiographs, US = ultrasound scan, ROM = range of motion.

On clinical examination, no macroscopic signs of fractures were detected just after birth. The neonates underwent a paediatric orthopaedic evaluation at a mean time of 40.8 h after delivery (12–72 h from birth). Clinical presentation was typical for fracture separation in 4/5 patients (injured elbow grossly swollen and painful, motionless upper limb, palpable crepitius).

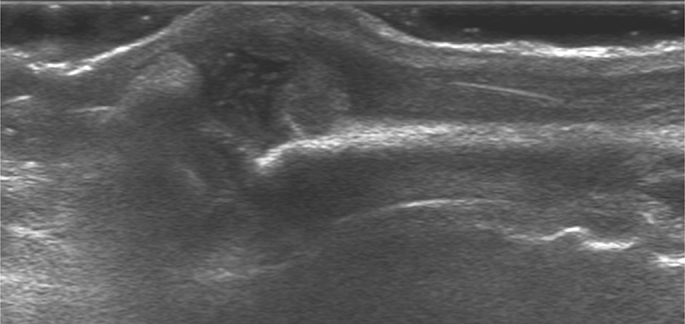

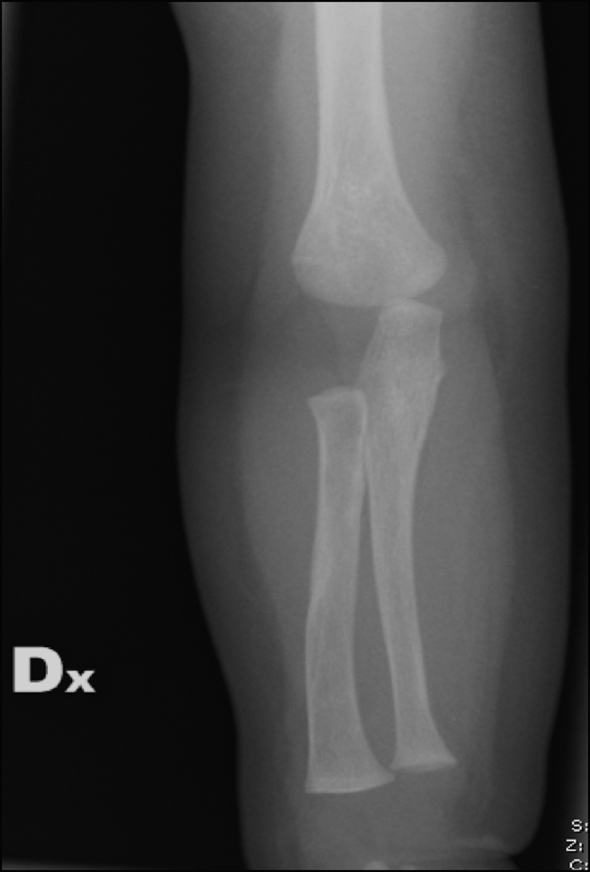

All the patients had standard radiographs of the arm and the elbow joint (Fig. 1). Two cases needed an added ultrasound for diagnosis (Fig. 2). In the premature neonate, the injury was erroneously diagnosed as an elbow dislocation but subsequent ultrasound examination revealed a postero-medial displacement of the distal epiphysis of the humerus.

Fig. 1.

Radiographs of elbow in newborn can often be interpreted as normal.

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound examination of the same patient in Fig. 1, showing a displaced fracture of the distal physis.

All the patients underwent gentle close manipulation, reduction under fluoroscopy and cast application. The above-elbow cast was applied with the elbow at 90 degrees of flexion. The cast was removed once adequate callus formation was seen on radiographs at a mean of 2 weeks, subsequent to which active elbow joint motion was permitted. In case No. 2 (Table 1), following a failed reduction, closed reduction and K-wire fixation was carried out, followed by recasting.

All the patients were followed up at the outpatient department with serial radiographs at 1, 2, 4 weeks, 6 months and 1 year (Fig. 3) where the functional outcome and the carrying angle of the elbow were clinically assessed (Fig. 4). Complications were also evaluated.

Fig. 3.

Follow-up radiographs at one year.

Fig. 4.

Full range of movements at one year follow-up.

Patients were followed up for a mean duration of 30 months (range 12–60 months). All of them showed full ROM of the elbow joint and a complete radiographic healing of the fracture. The fractures healed at a mean time of 15.5 days (range 13–18 days). One fracture healed with a varus of 5°. No other complications were noticed.

None of the patients had any rotational malalignment or deformity on follow-up examination. All the deformities observed at fracture healing were completely remodelled within 6 months with an anatomical radiographic alignment on both anterior-posterior and lateral views. No neurovascular damage or other complications were found. None of the parents reported unsatisfactory outcomes.

Discussion

Neonatal separation of the distal epiphysis of the humerus at birth, first reported in 1926 by Camera,19 is a rare and often misdiagnosed injury. A recent study by Sherr-Lurie et al20 reported an incidence of humerus fracture at birth of 0.09/1000 births and according to their study, only 2 of 92,882 live patients reviewed sustained a traumatic separation of the distal epiphysis of the humerus. In 2009 Jacobsen et al4 reviewed a series of 6 neonatal chondroepiphyseal injury in addition to 22 previous cases reported in the literature. Since then there have been only 14 cases further quoted.5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 20

The mechanism of injury usually described for separation of the epiphysis is hyperextension of the elbow or a backward torsion of the forearm with the elbow flexed.21 Because the physeal region is the weakest part of the distal humerus, rotational shear forces or excessive traction applied to extract the baby during the delivery could cause this kind of fracture. Consequently, it has been reported that following caesarean or a difficult dystocic vaginal delivery, the incidence is higher.2, 4 The clinical findings that may suggest displacement of the epiphysis of the distal humerus in a newborn are soft tissue swelling around the joint, instability, limitation of elbow movements and even pseudoparalysis of the upper limb.22 Typical of the chondro-epiphyseal injuries is the classical sign of “muffed crepitus” due to cartilaginous surfaces scratching together.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis is made with traumatic elbow dislocation, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, brachial plexus injury and genetic bone diseases (e.g. osteogenesis imperfecta). Child abuse should be also considered. In differentiating elbow dislocation and distal humeral epiphysis fracture, the three-point technique using the relationship between the medial humeral epicondyle, the olecranon process and the lateral humeral epicondyle has been suggested. However, when the elbow has an important swelling, these landmarks are difficult to find.

Plain radiographs are very difficult to be interpreted in newborns as the unossified distal humeral epiphysis is not visible and it is not possible to check the right alignment of the proximal radius and the capitellum, whose ossification centre often begins to ossify by 6 months of age.14 Nevertheless in neonates the typical medial displacement of radius and ulna seen at X-ray images may be considered diagnostic of fracture-separation because elbow traumatic dislocation has been never described in children under four years of age.4

Definitive confirmation of the suspicion of fracture separation is obtained by performing an X-ray examination at one week, when the periosteal reaction is clearly visible at the fracture site.5 For these reasons the diagnosis of fracture separation of distal humeral epiphysis may be sometime missed at birth as reported by Jacobsen et al.4 Four of their six patients described in their paper were in fact late diagnosed (9–30 days after being discharged from the hospital). In our series the diagnosis was made at a mean time of 40.8 h after birth.

Ultrasonography, which is able to visualize the cartilaginous epiphysis and its relationships with the ossified metaphysis,5 is a simple, noninvasive, easily available useful tool in differentiating elbow dislocation from fracture-separation. Ultrasound examination should be performed by a skilled radiologist without sedation but it may require uncomfortable and painful manipulation for positioning the injured limb.5, 6 MRI is the most accurate examination as it provides detailed visualization of the cartilage, bone and soft tissue in sagittal, coronal or oblique axis planes. However, this exam needs the baby to be under sedation or general anaesthesia,15, 16 which may require important organizing efforts that allow long waiting time and consequent delay in treatment. None of our patients needed MRI to confirm the right diagnosis. Nowadays a marginal role is left to arthrography because it has some drawbacks as invasivity and risk of infection.4, 22

Treatment

The treatment options for separation of distal humeral epiphysis differs among different authors but closed reduction and cast application under anaesthesia is the most frequent choice.20 Anatomical reduction is not difficult when the diagnosis is early performed,23 so that open surgery associated to pinning is very rarely reported in difficult reductions.22, 24 In our series percutaneous pinning was performed in a case of failed reduction that was estimated at risk for permanent deformity. Nevertheless, differently from what observed in childhood when an anatomical reduction of the fracture separation at the distal humerus always recommended, in newborns the spectacular remodelling properties of the neonatal bone allows a great tolerance.

Jacobsen et al4 reported excellent results in four patients with delayed diagnosis (underwent from 9 to 30 days after birth) whose fracture was not reduced but only immobilized in a cast for 2–4 weeks. The mode of immobilization may differ among different authors. Sherr-Lurie et al20 prefer reduction and cast application for 2 weeks with the upper limb held against the body. Similarly Dias et al6 reported a single case of full elbow movement with no deformity after conservative management with collar and cuff. Kasser and Beaty25 recommended treatment with closed reduction and cast with the elbow in 90° of flexion. Catena and Sénès9 suggested closed reduction under general anaesthesia, followed by immobilization for 2–3 weeks or sometimes a simple bandage as a good alternative to the classical cast. In the same series in one case, due to an important swelling of the elbow, a Dunlop traction was instituted for four days, followed by closed reduction and cast.

When, particularly in late diagnosed fracture, closed reduction is unstable, percutaneous pin fixation may be considered. De Jager and Hoffman26 performed K-wire fixation through a lateral approach in three cases with initial wrong diagnosis of lateral condylar fracture. Mizuno et al27 reported good results with no complication using an open reduction through a posterior approach with pinning. In our series we performed percutaneous pin fixation in a severely displaced fracture dated one week. The reduction was improved but it was not anatomical. Trusting in the spontaneous remodelling, the open approach was avoided obtaining a good clinical and radiological result at the follow-up.

Complication

A mild cubitusvarus, sporadically reported in literature, is the most common complication associated to fracture separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in neonates.4, 26 However it is not progressive because of not being caused by a permanent physeal injury.4 In our series we reported a 5° varus angle in only one patient. De Jager and Hoffman26 suggested that cubitusvarus is probably due to inadequate reduction, especially when the medial cortex is involved in the fracture and if the distal fragment is internally rotated. The substantially benign outcome, always reported for this lesion at birth, suggest that a conservative approach has to be preferred. This is particularly true in late diagnosed fracture when forceful manipulation may damage the physis. On this basis, reduction by open surgery seems unnecessary and hardly justified.

Conclusion

Distal humerus physeal separation at birth is extremely rare injuries. The clinician must always differentiate them from elbow dislocations since the two injuries can be easily confused. It is very important to pay attention to the clinical examination. Conventional radiographs are often difficult to interpret in the newborn and most of them would need additional imaging modalities such as ultrasonography or MRI for definitive diagnosis. Prompt closed reduction and casting gives excellent outcomes.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Daping Hospital and the Research Institute of Surgery of the Third Military Medical University.

References

- 1.Kim S.H., Szabo R.M., Marder R.A. Epidemiology of humerus fractures in the United States: nationwide emergency department sample, 2008. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:407–414. doi: 10.1002/acr.21563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhat B.V., Kumar A., Oumachigui A. Bone injuries during delivery. Indian J Pediatr. 1994;61:401–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02751901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madsen E.T. Fractures of the extremities in the newborn. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1955;34:41–74. doi: 10.3109/00016345509158066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsen S., Hansson G., Nathorst-Westfelt J. Traumatic separation of the distal epiphysis of the humerus sustained at birth. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2009;91:797–802. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navallas M., Díaz-Ledo F., Ares J. Distal humeral epiphysiolysis in the newborn: utility of sonography and differential diagnosis. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dias J.J., Lamont A.C., Jones J.M. Ultrasonic diagnosis of neonatal separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1988;70:825–828. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B5.3056949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Supakul N., Hicks R.A., Caltoum C.B. Distal humeral epiphyseal separation in young children: an often-missed fracture-radiographic signs and ultrasound confirmatory diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:W192–W198. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker A., Methratta S.T., Choudhary A.K. Transphyseal fracture of the distal humerus in a neonate. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catena N., Sénès F.M. Obstetrical chondro-epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus: a case report and review of literature. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:418–419. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabat D., Maini L., Gautam V.K. Neonatal separation of distal humeral epiphysis during Caesarean section: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011;19:376–378. doi: 10.1177/230949901101900325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Söyüncü Y., Cevikol C., Söyüncü S. Detection and treatment of traumatic separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in a neonate: a case report. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamaci S., Danisman M., Marangoz S. Neonatal physeal separation of distal humerus during cesarean section. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2014;43:E279–E281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph P.R., Rosenfeld W. Clavicle fractures in neonates. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:165–167. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150260043024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fader L.M., Laor T., Eismann E.A. MR imaging of capitellar ossification: a study in children of different ages. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-2921-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawant M.R., Narayanan S., O'Neill K. Distal humeral epiphysis fracture separation in neonates–diagnosis using MRI scan. Injury. 2002;33:179–181. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa M., Owen-Johnstone S., Tucker J.K. The value of MRI in the assessment of an elbow injury in a neonate. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2001;83:544–546. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White S.J., Blane C.E., DiPietro M.A. Arthrography in evaluation of birth injuries of the shoulder. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1987;38:113–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen P.E., Barnes D.A., Tullos H.S. Arthrographic diagnosis of an injury pattern in the distal humerus of an infant. J Pediatr Orthop. 1982;2:569–572. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camera U. Total, pure, traumatic detachment of inferior humeral epiphysis. Chir Org Mov. 1926:294–316. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherr-Lurie N., Bialik G.M., Ganel A. Fractures of the humerus in the neonatal period. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:363–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siffert R.S. Displacement of the distal humeral epiphysis in the newborn. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1963;45:165–169. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett W.P., Almquist E.A., Staheli L.T. Fracture separation of the distal humeral physis in the newborn. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:617–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen R.K., Bedi G.S., Nagi O.N. Fracture epiphyseal separation of the distal humerus. Australas Radiol. 1998;42:271–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1998.tb00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman J.M., Weiner D.S. Neonatal fracture-separation of the distal humeral chondroepiphysis: a case report. Orthopedics. 1980;3:875–879. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19800901-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaty J.H., Kasser J.R., editors. Rockwood and Wilkins' Fractures in Children. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. Fractures involving the entire distal humeral physis; pp. 533–593. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Jager L.T., Hoffman E.B. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1991;73:143–146. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizuno K., Hirohata K., Kashiwagi D. Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis in young children. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1979;61:570–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]