Abstract

The discovery of large, complex, internal canals within the rostra of fossil reptiles has been linked with an enhanced tactile function utilised in an aquatic context, so far in pliosaurids, the Cretaceous theropod Spinosaurus, and the related spinosaurid Baryonyx. Here, we report the presence of a complex network of large, laterally situated, anastomosing channels, discovered via micro-focus computed tomography (μCT), in the premaxilla and maxilla of Neovenator, a mid-sized allosauroid theropod from the Early Cretaceous of the UK. We identify these channels as neurovascular canals, that include parts of the trigeminal nerve; many branches of this complex terminate on the external surfaces of the premaxilla and maxilla where they are associated with foramina. Neovenator is universally regarded as a ‘typical’ terrestrial, predatory theropod, and there are no indications that it was aquatic, amphibious, or unusual with respect to the ecology or behaviour predicted for allosauroids. Accordingly, we propose that enlarged neurovascular facial canals shouldn’t be used to exclusively support a model of aquatic foraging in theropods and argue instead that an enhanced degree of facial sensitivity may have been linked with any number of alternative behavioural adaptations, among them defleshing behaviour, nest selection/maintenance or social interaction.

Introduction

Neovenator salerii is an allosauroid theropod from the Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight, UK (Barremian, Early Cretaceous)1, 2, known from a partial skeleton (Museum of Isle of Wight Geology (MIWG) 6348) that comprises extensive cranial, axial, and appendicular material preserved in excellent three-dimensional condition. Neovenator is a member of the tetanuran clade Allosauroidea, as evidenced by a suite of cranial and postcranial characters2–5. Within Allosauroidea, recent work identifies it a basal member of Neovenatoridae6.

A deep, laterally compressed (oreinirostral) skull, large, ziphodont teeth, and a facial and mandibular skeleton considered typical for large, predatory theropods indicate that Neovenator was a terrestrial predator that attacked and dispatched vertebrate prey in a manner typical for allosauroids. Neovenator has been assumed to have been an apex terrestrial predator, like its carcharodontosaurian close relatives7. Analysis of the feeding dynamics of the closely-related Allosaurus fragilis indicate powerful ventroflexive angular acceleration of the skull, coupled with minimal shake feeding8. Minimal tooth-to-bone contact and the targeting of smaller/juvenile individuals are also predicted9. There are no indications that Neovenator was unusual in ecology or prey choice with respect to other allosauroids and it is assumed to have been a predator of ornithopods and other mid-sized dinosaurs, a hypothesis supported by bite marks on an associated specimen of the iguanodontian Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis.

The osteology of Neovenator is well-understood2. However, we were intrigued by enlarged foramina present on both the lateral surface of the premaxilla, occasionally set within shallow grooves2, and on the anterior ramus of the maxilla and hypothesised that they might be indicative of a rostral neuroanatomy similar to that reported in spinosaurids10, and more recently, tyrannosaurids11. Complex neuroanatomical systems present in the rostra of many vertebrates have been associated with a function in prey detection. However, poor preservation typically means that they are not sufficiently well-preserved to allow detailed examination12. Mini-focus medical CT imaging of the Cretaceous spinosaurid Spinosaurus aegyptiacus was previously employed to investigate the internal structure of the enlarged foramina on the surface of its premaxilla. The exceptional volume of these neuroanatomical structures has been linked to an aquatic tactile ability, consistent with narial position, jaw and tooth shape, limb proportions, and reduced medullary cavities in the long bones which have been regarded as indicative of an amphibious or aquatic mode-of-life10. These rostral structures of Spinosaurus were thus regarded as analogous to the dermal pressure receptors (DPR)10 present in crocodylians.

Here, we revisit the cranial morphology of the Isle of Wight theropod Neovenator using microfocus μCT to investigate the distribution of its rostral foramina and any internal preservation. We use these data to inform inferences about the palaeobiology and behaviour of Neovenator and other large tetanuran theropods, whilst standardising our results to facilitate further analysis of theropod/dinosaurian cephalic vasculature.

Results

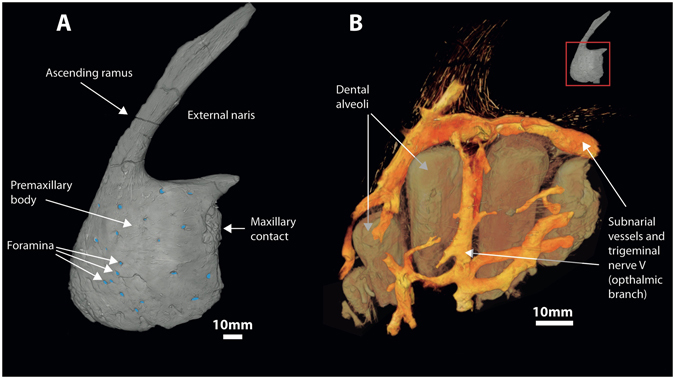

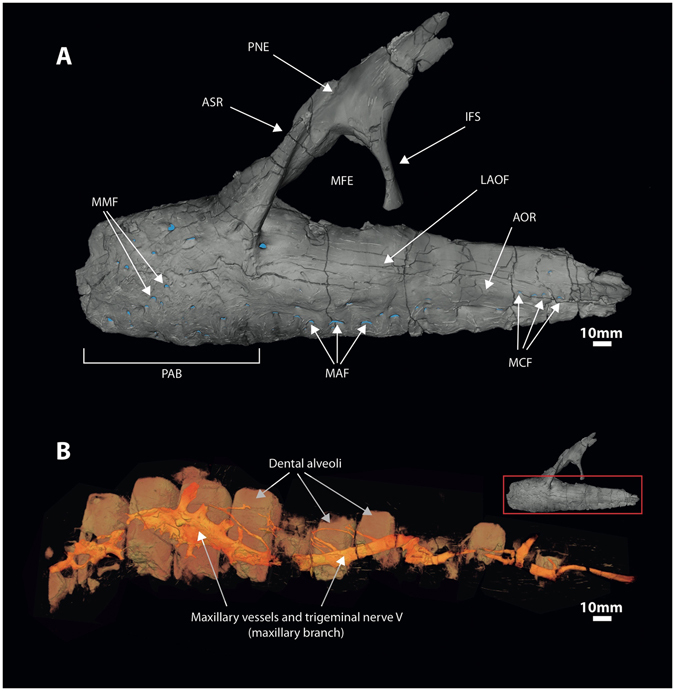

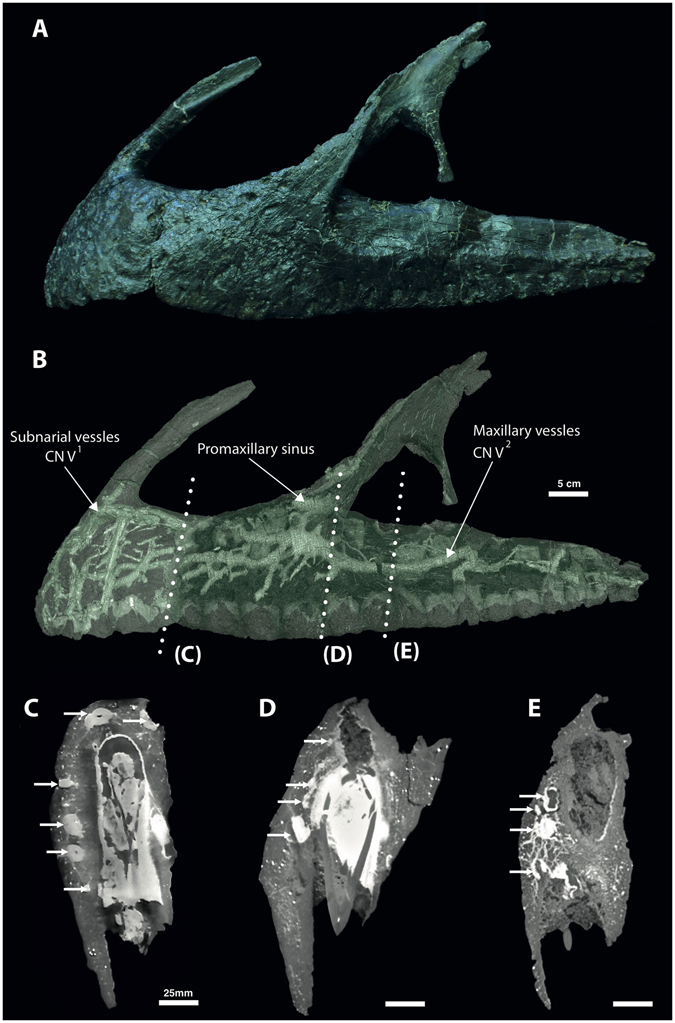

Of the material scanned, the left premaxilla and maxilla revealed the best internal preservation. A complex network of canals branch extensively in both elements (Figs 1, 2 and 3); these canals are located lateral to the dental alveoli (they are absent from the medial side), terminating on the external surfaces of the bones (Fig. 3, I-III). In both bones, several canals exit via foramina on the bone surface (Figs 1A and 2B), with the premaxilla and preantorbital body presenting the most (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Complex anastomosing neurovasculature surrounding infilled dental alveoli of the premaxilla of Neovenator. (A) Volume rendering of left premaxilla in lateral view with foramina highlighted (blue). (B) Volume rendering of infilled voids.

Figure 2.

Complex anastomosing neurovasculature surrounding infilled dental alveoli of the maxilla of Neovenator. (A) Volume rendering of left maxilla in lateral view with foramina highlighted (blue). (B) Volume rendering of infilled voids. Abbrevations: aor: antorbital ridge; asr: ascending ramus; ifs: interfenestral strut; laof: lateral antorbital fossa; maf: maxillary alveolar foramina; mcf: maxillary circumfenestra foramina; mfe: maxillary fenestra; mmf: medial maxillary foramina; pab: preantorbital body; pne: pneumatic excavation.

Figure 3.

(A) Articulated premaxilla and maxilla of Neovenator holotype MIWG 6348 in left lateral view (Credit: Roger Benson). (B) Volume rendering of the segmented neurovascular network overlaid on the articulated premaxilla and maxilla. (C–E) μCT virtual sections showing lateral placement of the neurovasculature (white arrows).

Table 1.

Foramina count, neurovascular volume, bone volume, and ratio (%) in the premaxilla and maxilla of Neovenator.

| Element | Bone Anatomy | Foramina count | Nerve volume (cm3) | Bone volume (cm3) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premaxilla | Premaxillary body | 47 | 1.1 | 15.0 | 7.3 |

| Maxilla | Preantorbital body | 40 | 9.2 | 164.0 | 5.6 |

| Anterior body | 61 | 11.7 | 261.3 | 4.5 | |

| Jugal ramus | 17 | 1.5 | 67.8 | 2.2 |

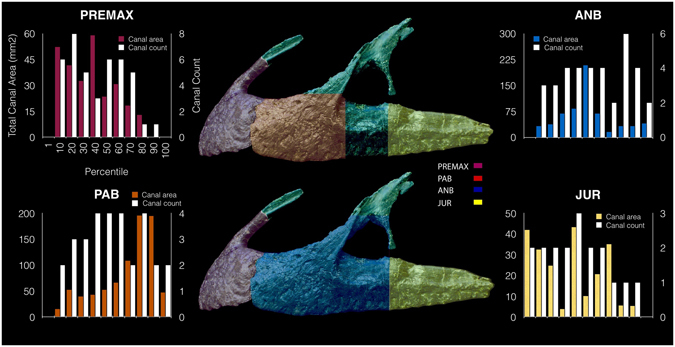

We interpret all of these branching structures as part of the neurovascular system, independent of and separate from the pneumatic system. Branching is most complex in the premaxilla where much of the premaxillary body is occupied by canals of a complex, dendritic or anastomosing form (Figs 1 and 3B). One premaxillary canal appears to ascend dorsally through at least the base of the nasal process of the premaxilla, although its dorsal extent is unclear. Much of the length of the maxilla is occupied by a large, serpentine canal that extends through the maxillary body at mid-height (Figs 2B and 3B). At a point ventral to the base of the ascending ramus, the canal is more dorsally positioned and possesses a ganglion-like thickening that sends off dendritic branches dorsally, ventrally, and anteriorly. This thickening is denoted in Fig. 4 as the elevated plateau within the area data for the preantorbital body, coupled with a decrease in dendricity. It is associated with the presence of especially large foramina near the base of the ascending ramus, while ventral branches pass dorsal and lateral to the alveoli. The majority of the foramina associated with this maxillary branch are found on the preantorbital body, forming medial maxillary foramina, mirroring the most dendritic sections of the maxillary neurovascular canals (Figs 2B, 3B and 4). This is reflected by the increased canal:bone ratio seen in Table 1 compared to the anterior body as a whole. The remainder of the foramina are found ventrally along the tooth row (maxillary alveolar foramina), as well as along the antorbital ridge (maxillary circumfenestra foramina) (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the latter two foramina types appear to have very little interaction with the maxillary branch of the canals (Figs 2 and 3B), and these various canals and their sub-branches are highly variable in size. Taken together, these structures occupy at least 7.3% and 6.7% of the internal volume of the premaxilla and maxilla, respectively (Table 1), and an accessory sinus is linked to the premaxillary fenestra at the base of the ascending ramus of the maxilla. Several branches of these maxillary neurovascular structures closely approach the sinus although they do not appear to interact with it directly.

Figure 4.

Lateral view of left premaxilla and maxilla, denoting maxillary anatomy as suggested by Hendrickx and Mateus56. Graphs denote changes in canal area versus canal count (i.e. number of observable canals per slice) at various regions of premaxillary and maxillary anatomy, based on data from Supplementary Table S1. Abbreviations: premax: premaxilla; pab: preantorbital body; anb: anterior body; jur: jugal ramus.

Discussion

The presence of foramina on the lateral surfaces of the premaxilla and maxilla are typical, widespread amniote features13 and only rarely are they given more than fleeting mention in descriptions and analyses. Nevertheless, a long-standing debate concerns the size, number, and distribution of these foramina in non-avialan dinosaurs as well as the presence of either keratinous rhamphotheca or lip-like and/or cheek-like extraoral tissues14–22. It is currently thought that keratinous rhamphotheca were present in ornithischians and in such theropods as ornithomimosaurs, therizinosaurs, oviraptorosaurs and some ceratosaurs; the condition in other lineages of non-avialan theropods remains ambiguous but the absence in Neovenator of osteological correlates linked to the presence of rhamphotheca, including bone spicules and shallow, obliquely oriented foramina23, indicates that such tissues were absent. Typically, fewer and larger foramina are seen in organisms with extensive extraoral tissues (e.g. lips, 13), and the presence of a large number of foramina on the premaxilla and maxilla in Neovenator suggests that whatever extraoral tissue was present was immobile. The rugosity of bones in this region is comparable to that of abelisaurids and carcharodontosaurids2, although Neovenator is somewhat atypical regarding foramina count being most comparable to abelisaurids such as Majungasaurus 24 where sculpted cranial morphology and foramina count have been linked with dermal specialisations. It is important to note that the presence of cornified, specialised dermal tissue is not itself incompatible with the presence of enhanced sensory capabilities; the crocodylian face is covered by an extensively cracked epidermis, nearly twice as thick as anywhere else on the body25, yet these archosaurs are capable of extraordinary facial sensitivity. Furthermore, the presence of a sensitive scaly integument has been suggested for the tyrannosaurid Daspletosaurus horneri 11.

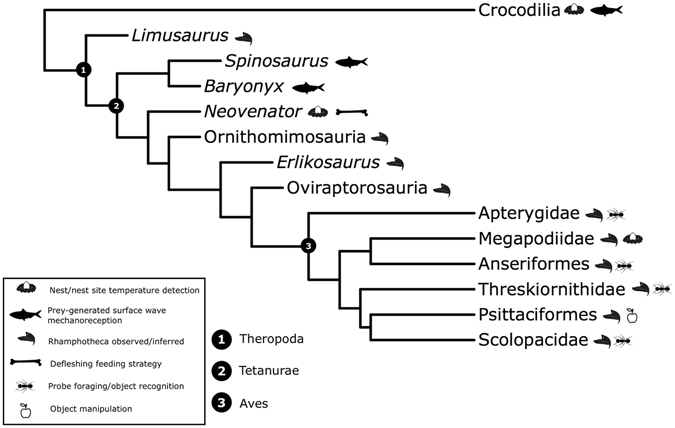

In modern archosaurs, the function of foramina is easier to ascertain as they are often associated with mechanoreceptors (Fig. 5). In the rostrum of birds for example, Grandry and Herbst corpuscles give probe foragers (i.e., Apterygidae, Scolopacidae, and Threskiornithidae) the tactile ability to recognise prey items during foraging26. In Anseriformes, neurovascular foramina on the tips and ridges of the beak allow for the detection, recognition, and transport of food27, while enhanced object manipulation is seen in Psittaciformes28. Several ratite species also show advanced bill sensitivity, however the extent of this is yet to be tested histologically29. In crocodylians, aforementioned mechanoreception is similarly present in the rostrum, with neurovascular foramina representing an exit for the highly sensitive branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V)30. The existence of substantial innervation within the rostrum, associated with foramina, has also been associated with hunting and foraging in several other Mesozoic fossil reptiles10–12. A similar structure is seen in extant varanids30, 31, however, it is less dendritic than is the case in Neovenator, and squamate’s premaxillae lack the foramina seen in archosaurs. Varanids were thus not considered further for the purpose of this study.

Figure 5.

A schematic phylogeny representing the archosaurs mentioned in the text, and their inferred palaeoecology as a result of the presence of mandibular foramina an/or internal neurovascular structures.

We suggest that the structures we have described in Neovenator represent branches of the trigeminal nerve similar to those seen in extant crocodylians30. These neurovascular canals can be divided into two branches; in the premaxilla, they form part of the ophthalmic (CN V1) division of the trigeminal nerve, specifically, the premaxillary branch of its medial nasal ramus (Fig. 1)24. This is the smallest of the three divisions and has a purely sensory function32. The maxillary (CN V2) branch occupies the maxilla, relaying information from the upper jaw and teeth (Fig. 2)9, 32. Our identification of this structure in Neovenator as the ophthalmic and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve is consistent with its termination at numerous neurovascular foramina that pepper the bones of the skull (Figs 1A and 2A)9, 12, 13.

A portion of the subnarial artery and vein, as well as maxillary vessels, are most likely also present in Neovenator (Fig. 2B), with the latter merging with the nerve to form the maxillary canal33. However, it should be noted that making comparisons with the cranial vasculature of extant archosaurs is hindered by the highly modified nature of their skulls relative to those of Mesozoic theropods; for example, the crocodylian skull is platyrostral as opposed to oreinirostral, the antorbital fenestra is absent, and a secondary palate is present34. In addition, it is difficult to discern differences between neural and vascular tissue in fossils due to issues of preservation. Furthermore, the large size discrepancy present between extinct dinosaurs like Neovenator and extant taxa increases the difficulty in assigning functions to extinct taxa based on osteological structures present in the latter, arguably requiring “extrapolation beyond empirical data”35.

The extensive cephalic vasculature of crocodylians has a thermoregulatory function, as both the oral and nasal regions act as major cranial sites of thermal exchange, with the latter particularly vascularised34. Similarly, many extant birds employ cephalic vasculature for thermoregulatory means36. In both of these extant archosaur groups, a highly vascularised oral region can form a palatal plexus, with arterial and venous branches of the palatine blood vessels anastomosing to form a large surface area for thermal exchange34, 36. The highly vascularised nasal regions in birds have also been shown to be areas of thermal exchange36–38; a similar pattern is present in crocodylians where a thermoregulatory function has yet to be rigorously tested34. It is possible that a similar function was present in Neovenator. However, although the narrow rostrum would have reduced the surface area for palatal heat exchange, anteroventral distribution of the canals and their associated foramina is surprising within the context of a thermoregulatory function as this position would not make use of the entirety of the lateral surfaces of these two bones. Furthermore, there is currently no evidence for a plexus-type complex in Neovenator. For these reasons we consider it unlikely that temperature control was an important function of these neurovascular structures.

Returning to our trigeminal nerve hypothesis, innervation linked to external integumentary sensory organs (ISO) in extant crocodylians allows the snout to perform as a specialised tactile organ that perhaps possesses ‘sensitivity greater than primate fingertips’39. Tests on juvenile alligators have shown how ISOs aid mechanoreception, the detection of prey-generated ripples, accurate biting, and ‘tactile discrimination of items held within the jaws’39. Erickson et al.40 also regarded ISOs as a tool to determine the application of bite force when feeding. However, mechanoreception is not the only function of ISOs in crocodylians; these organs also have a combined thermo- and chemosensory role as well as responding to pressure41.

Within some Mesozoic theropods, the presence of enlarged foramina on the rostrum as well as a large neurovascular cavity in Spinosaurus (and potentially Baryonyx 12), documented via μCT-scanning, have been linked to a specialised nervous system and correlated with a semi-aquatic lifestyle (Fig. 5)10, 12. However, despite the significant number of theropod skulls that have now been subjected to μCT scanning, neurovascular anatomy linked with exceptional tactile ability has only been described in spinosaurids. The new data presented here, coupled with the recent finding in tyrannosaurids11, indicate that spinosaurids were not exceptional within Theropoda in terms of their facial neuroanatomy, and that Neovenator, apparently a ‘typical’ terrestrial theropod lacking any specialisations for amphibious or aquatic life, possessed a comparable degree of neuroanatomy and presumed rostral/facial sensitivity. Although it remains possible that Neovenator was a specialized aquatic forager and that this unusual configuration can be linked to such a lifestyle, this inference is not reflected in any other aspect of Neovenator’s anatomy, or from the palaeoecological and palaeoenvironmental context in which Neovenator, other neovenatorids, carcharodontosaurians, and allosauroids are preserved. While opportunistic foraging of aquatic prey remains possible for Neovenator, combined evidence contradicts a fundamental reinterpretation of this animal’s palaeoecology.

What appears much more parsimonious is that a previously under-appreciated degree of rostral and facial sensitivity was typical for large tetanurans, and that this played a role in how and where bites were applied, as well as in other aspects of prey-handling and behaviour. Two-dimensional analysis of dental microwear (Barker et al. in preparation) suggests that Neovenator actively avoided tooth-bone contact; two maxillary teeth bear scratch-dominated enamel with minimal pitting, a configuration characteristics of extant carnivores that avoid bone contact (e.g. cheetahs)42, 43. We therefore speculate that a sensitive snout would be useful when defleshing a carcass, imparting enhanced sensitivity to allow the animal to carefully differentiate between meat and bone when feeding. In addition, this ability would help explain the rarity of evidence for tooth-bone contact in the non-tyrannosaurid Mesozoic fossil record9, 44. We also note that enhanced facial sensitivity may potentially have played a role in intraspecific communication, consistent with data suggesting that ritualised face-biting – and thus facial contact in general – was part of theropod behavioural repertoire11, 45. Coronal CT slices are also known for a ventrally compressed Tyrannosaurus rex 46 specimen and reveal a (presumably deformed) maxillary channel and nerve (V2). Tyrannosaurids show evidence of cranio-facial biting, this presumably reflecting intraspecific combat behaviour45, 47–49. It would be of interest to compare the size of the neurovasculature in tyrannosaurids to the other theropods discussed here (e.g. Neovenator) and assess whether this is simply a retained plesiomorphic trait or was reduced, perhaps as an evolutionary response either to this aggressive behaviour or to the unusual feeding strategy (involving increased tooth-bone contact) of this clade. A thermosensory role also remains possible, responses to thermal stimuli potentially proving useful within the context of finding and maintaining a nest environment by analogy with behaviour present in crocodylians50–53 as well as megapode birds54. It is feasible to envisage Neovenator employing its snout whilst engaging in nesting behaviour, especially given that crocodylians and most non-avian theropods appear to share mound building behaviour55.

In conclusion, the identification of a complex and highly developed neurovascular network in the rostrum of Neovenator, an otherwise ‘typical’ allosauroid theropod, places previous inferences of such structures in spinosaurids in a new context. While it is possible that spinosaurids secondarily adapted the neuroanatomy described here for aquatic foraging56, it is also possible that the relevance of facial sensitivity to this behaviour has been over-stated. Further analyses on the morphology and distribution of cranial nerves within Dinosauria, using their extant archosaur cousins as reference, is required in order to better understand and quantitatively assess the use of facial sensitivity in these animals, a concept supported by foramina studies in extant ratites29. By standardising our results using percentiles across key anatomical references, our data can be used to facilitate such further analysis.

Material and Methods

Both left and right premaxillae, the left maxilla, and the right nasal from the Neovenator holotype (MIWG 6348) were scanned at the μ-VIS X-Ray Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton (UK), using the custom designed Nikon/Metris dual source high energy micro-focus walk-in enclosure system. A 450 kVp source was used, coupled with a 1621 PerkinElmer cesium-iodide detector. Peak voltage was set at 400 kVp and the current at 314 μA (125.6 W). A total of 3142 projections (16 frames per projection) were collected during a 360° rotation, with each projection occurring over an exposure time of 177 ms. The raw projection data were reconstructed into 3D volumes (32-bit raw) using isotropic voxels (voxel dimension = 124.7 µm3) by means of Nikon’s reconstruction software (CT Pro 3D, v. XT 2.2 SP10), which uses a filtered back projection algorithm.

Subsequently the reconstructed 32-bit volumes were downsampled to 8-bit (raw) volume files to reduce processing power and computational load of the processing workstations. The 8-bit volumes were then imported to VG Studio Max (version 2.1 Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) for further processing and visualisation. Segmentation in Avizo® was predominantly performed manually on a slice-by-slice basis using the “Brush” tool, although semi-automatic segmentation was possible on certain elements using the “Magic wand” tool, at grey-scale values of 197 with the tolerance set at 45. Due to resolution limitations, we focused our quantitative analyses on the lower boundary estimate of the structure and volume of the neurovascular canals. Our results and discussion are mainly based on the left premaxilla and maxilla, where the relevant internal structures are best preserved (Figs 1, 2 and 3). Figures were compiled and annotated in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, California), using terminology based on Torvosaurus material57. Percentiles (Supplementary Table S1) were generated using the scan slice numbers in order to standardise our results.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the μ-VIS X-Ray imaging centre of the University of Southampton for provision of tomographic imaging facilities, supported by EPSRC grant EP-H01506X. Thanks to Alex Peaker, Dinosaur Isle (Sandown, Isle of Wight), for access to the specimen.

Author Contributions

C.T.B., G.D., and D.N. conceived the study. O.L.K. developed the imaging protocol, carried out the μCT scans and wrote the methodology. C.T.B., with the help of E.N., prepared the data. C.T.B., E.N. and D.N. guided the data analysis. All five authors contributed to writing the paper, and all approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-03671-3

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hutt S, Martill DM, Barker MJ. The first European allosaurid dinosaur (Lower Cretaceous, Wealden Group, England) N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Mb. 1996;1996:635–644. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brusatte, S. L., Benson, R. B. J. & Hutt, S. The osteology of Neovenator salerii (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Wealden Group (Barremian) of the Isle of Wight. Monograph of the Palaeontographical Society London. 162(631), 1–75, pls 1–45 (2008).

- 3.Holtz TR. A new phylogeny of the carnivorous dinosaurs. Gaia. 2000;15:5–61. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauhut OWM. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 2003;69:1–213. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtz, T. R., Molnar, R. E. & Currie, P. J. Basal Tetanurae in The Dinosauria 2nd edition (eds. Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., Osmolska, H.) 71–110 (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2004).

- 6.Benson RBJ, Carrano MT, Brusatte SL. A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic. Naturwissenschaften. 2010;97:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00114-009-0614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanno L. E. & Makovicky, P. J. Neovenatorid theropods are apex predators in the Late Cretaceous of North America. Nat. Commun. 4 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Snively, E., Cotton, J. R., Ridgely, R. & Witmer, L. M. Multibody dynamics model of head and neck function in Allosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda), Palaeontol. Elect. 16(2), 11A 29p (2013).

- 9.Hone DWE, Rauhut OWM. Feeding behaviour and bone utilization by theropod dinosaurs. Lethaia. 2010;43:232–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.2009.00187.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim N, et al. Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science. 2014;345(6204):1613–1616. doi: 10.1126/science.1258750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr TD, Varricchio DJ, Sedlmayr JC, Roberts EM, Moore JR. A new tyrannosaur with evidence for anagenesis and crocodile-like facial sensory system. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44942. doi: 10.1038/srep44942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foffa D, Sassoon J, Cuff AR, Mavrogordato MN, Benton MJ. Complex rostral neurovascular system in a giant pliosaur. Naturwissenschaften. 2014;101(5):453–456. doi: 10.1007/s00114-014-1173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morhardt, A. C. Dinosaur smiles: Do the texture and morphology of the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary bones of sauropsids provide osteological correlates for inferring extra-oral structures reliably in dinosaurs? (Master’s thesis) Western Illinois University. (2009).

- 14.Weishampel DB, Jianu. C, Csiki Z, Norman DB. Osteology and phylogeny of Zalmoxes (ng), an unusual euornithopod dinosaur from the latest Cretaceous of Romania. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2003;1(2):65–123. doi: 10.1017/S1477201903001032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witmer LM, Ridgely RC. The paranasal air sinuses of predatory and armored dinosaurs (Archosauria: Theropoda and Ankylosauria) and their contribution to cephalic structure. Anat. Rec. 2008;291(11):1362–1388. doi: 10.1002/ar.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett, P. M. Tooth wear and possible jaw action of Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen and a review of feeding mechanisms in other thyreophoran dinosaurs in The Armored Dinosaurs (ed. Carpenter, K.) 45 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

- 17.Kobayashi, Y. & Barsbold, R. Anatomy of Harpymimus okladnikovi Barsbold and Perle 1984 (Dinosauria; Theropoda) of Mongolia in The carnivorous dinosaurs (ed. Carpenter, K.) 97–126 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005).

- 18.Norell MA, Makovicky P, Currie PJ. The beaks of ostrich dinosaurs. Nature. 2001;412:873–874. doi: 10.1038/35091139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lautenschlager S. Cranial myology and bite force performance of Erlikosaurus andrewsi: a novel approach for digital muscle reconstructions. J. Anat. 2013;222:260–272. doi: 10.1111/joa.12000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lautenschlager S, Witmer LM, Altangerel P, Zanno LE, Rayfield EJ. Cranial anatomy of Erlikosaurus andrewsi (Dinosauria, Therizinosauria): new insights based on digital reconstruction. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2014;34(6):1263–1291. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2014.874529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuff A, Rayfield EJ. Retrodeformation and muscular reconstruction of ornithomimosaurian dinosaur crania. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1093. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yates AM, Bonnan MF, Neveling J, Chinsamy A, Blackbeard MG. A new transitional sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and the evolution of sauropod feeding and quadrupedalism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Bio. 2010;277(1682):787–794. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hieronymus TL, Witmer LM, Tanke DH, Currie PJ. The facial integument of centrosaurine ceratopsids: morphological and histological correlates of novel skin structures. Anat. Rec. 2009;292(9):1370–1396. doi: 10.1002/ar.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampson SD, Witmer LM. Craniofacial anatomy of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the late Cretaceous of Madagascar. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2007;27(S2):32–104. doi: 10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[32:CAOMCT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milinkovitch MC, et al. Crocodile head scales are not developmental units but emerge from physical cracking. Science. 2013;339(6115):78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1226265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham SJ, et al. The anatomy of the bill tip of kiwi and associated somatosensory regions of the brain: comparisons with shorebirds. PLoS one. 2013;8(11):e80036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkhoudt H. The morphology and distribution of cutaneous mechanoreceptors (Herbst and Grandry corpuscles) in bill and tongue of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos L.) Neth. J. Zool. 1980;50:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demery ZP, Chappell J, Martin GR. Vision, touch and object manipulation in Senegal parrots Poicephalus senegalus. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Bio. 2011;278(1725):3687–3693. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crole, M. R. & Soley, J. T. (2017), Bony pits in the ostrich (Struthio camelus) and emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) bill tip. Anat. Rec.. Accepted Author Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.George ID, Holliday CM. Trigeminal nerve morphology in Alligator mississippiensis and its significance for crocodyliform facial sensation and evolution. Anat. Rec. 2013;296:670–680. doi: 10.1002/ar.22666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellairs ADA. Observation on the snout of Varanus, and a comparison with that of other lizards and snakes. J. Anat. 1949;83:116–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shankland WE. The trigeminal nerve. Part II: the ophthalmic division. Cranio. 2001;19(1):8–12. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2001.11746145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benoit J, Manger PR, Rubidge BS. Palaeoneurological clues to the evolution of defining mammalian soft tissue traits. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25604. doi: 10.1038/srep25604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porter WR, Sedlmayr JC, Witmer LM. Vascular patterns in the heads of crocodylians: blood vessels and sites of thermal exchange. J. Anat. 2016 doi: 10.1111/joa.12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourke JM, Witmer LM. Nasal conchae function as aerodynamic baffles: Experimental computational fluid dynamic analysis in a turkey nose (Aves: Galliformes) Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2016;234:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter WR, Witmer LM. Avian cephalic vascular anatomy, sites of thermal exchange, and the rete ophthalmicum. Anat. Rec. 2016;299(11):1461–1486. doi: 10.1002/ar.23375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Midtgård U. Scaling of the brain and the eye cooling system in birds: a morphometric analysis of the rete ophthalmicum. J. Exp. Zool. 1983;225:197–207. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402250204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Midtgård U. Blood vessels and the occurrence of arteriovenous anastomoses in the cephalic heat loss areas of mallards, Anas platyrhynchos (Aves) Zoomorphology. 1984;104:323–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00312014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leitch DB, Catania KC. Structure, innervation and response properties of integumentary sensory organs in crocodylians. J. Exp. Biol. 2012;215:4217–4230. doi: 10.1242/jeb.076836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erickson GM, Gignac PM, Steppan SJ, Lappin AK, Vliet KA, Brueggen JD, Inouye BD, Kledzik D, Webb GJW. Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodylians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di-Poï N, Milinkovitch MC. Crocodylians evolved scattered multi-sensory micro-organs. EvoDevo. 2013;4(19):1. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Valkenburgh B, Teaford MF, Walker A. Molar microwear and diet in large carnivores: inferences concerning diet in the sabertooth cat, Smilodon fatalis. J. Zool. Lond. 1990;222(2):319–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb05680.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schubert BW, Ungar PS, DeSantis LRG. Carnassial microwear and dietary behaviour in large carnivorans. J. Zool. 2010;280(3):257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00656.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Amore DC, Blumenschine RJ. Komodo monitor (Varanus komodoensis) feeding behavior and dental function reflected through tooth marks on bone surfaces, and the application to ziphodont paleobiology. Paleobiology. 2009;35(4):525–552. doi: 10.1666/0094-8373-35.4.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanke DH, Currie PJ. Head-biting behavior in theropod dinosaurs: paleopathological evidence. Gaia. 1998;15:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brochu CA. Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2003;22(sup4):1–138. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2003.10010947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hone DWE, Tanke DH. Pre-and postmortem tyrannosaurid bite marks on the remains of Daspletosaurus (Tyrannosaurinae: Theropoda) from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. PeerJ. 2015;3:e885. doi: 10.7717/peerj.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson JE, Henderson MD, Scherer RP, Vittore CP. Face biting on a juvenile tyran- nosaurid and behavioural implications. Palaios. 2009;24:780–784. doi: 10.2110/palo.2009.p09-056r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bell PR, Currie PJ. A tyrannosaur jaw bitten by a confamilial: scavenging or fatal agonism? Lethaia. 2010;43:278–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1502-3931.2009.00195.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith, A. M. A. The sex and survivorship of embryos and hatchlings of the Australian freshwater crocodiles, Crocodylus johnstoni. (PhD thesis) Australian National University, Canberra (1987).

- 51.Webb G. & Manolis C. Crocodiles of Australia. (Reed Books Pty. Ltd., Sydney) (1998).

- 52.Murray, J. D. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction, Third Edition (Springer-Verlag, New York) 112 (2002).

- 53.Somaweera R, Shine R. Nest-site selection by crocodiles at a rocky site in the Australian tropics: Making the best of a bad lot. Austral Ecol. 2013;38:313–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2012.02406.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones, D. N., Dekker, R. W. R. J & Roselaar, C. S. The Megapodes 1–262 (Oxford) (1995).

- 55.Tanaka K, Zelenitsky DK, Therrien F. Eggshell Porosity Provides Insight on Evolution of Nesting in Dinosaurs. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Läng E, et al. Unbalanced food web in a Late Cretaceous dinosaur assemblage. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2013;381:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hendrickx C, Mateus O. Torvosaurus gurneyi n. sp., the Largest Terrestrial Predator from Europe, and a Proposed Terminology of the Maxilla Anatomy in Nonavian Theropods. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e88905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.