Abstract

Humans and other large-brained hominins have been proposed to increase energy turnover during their evolutionary history. Such increased energy turnover is plausible, given the evolution of energy-rich diets, but requires empirical confirmation. Framing human energetics in a phylogenetic context, our meta-analysis of 17 wild non-human primate species shows that daily metabolizable energy input follows an allometric relationship with body mass where the allometric exponent for mass is 0.75 ± 0.04, close to that reported for daily energy expenditure measured with doubly labelled water in primates. Human populations at subsistence level (n = 6) largely fall within the variation of primate species in the scaling of energy intake and therefore do not consume significantly more energy than predicted for a non-human primate of equivalent mass. By contrast, humans ingest a conspicuously lower mass of food (−64 ± 6%) compared with primates and maintain their energy intake relatively more constantly across the year. We conclude that our hominin hunter–gatherer ancestors did not increase their energy turnover beyond the allometric relationship characterizing all primate species. The reduction in digestive costs due to consumption of a lower mass of high-quality food, as well as stabilization of energy supply, may have been important evolutionary steps enabling encephalization in the absence of significantly raised energy intakes.

Keywords: allometry, food intake, energy balance, seasonal variation, hominins

1. Background

Humans and other large-brained hominins have been proposed to undergo an increased energy turnover during their evolutionary history and/or to evolve peculiar energy allocation trade-offs between growth, maintenance and reproduction relative to other primates [1–3]. Comparison of basal metabolic rate between modern humans and chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, suggests that basal energy requirements increased by approximately 19% during hominin evolution, though the available data are very limited [1,2]. Similarly, the available data on total daily energy expenditure (TEE) in humans and apes have been interpreted as indicating greater energy turnover in humans compared with non-human primates (e.g. 27% greater than chimpanzees and bonobos, [2]). At some point of hominin evolution, a shift towards an energy-rich diet [1,4,5] and later towards cooked foods, with an increased energy extraction per unit mass compared with raw foods [6,7], could have sustained the increased energy demand of a larger brain (among other possible sources of energy [2]).

Nonetheless, our understanding of the extent to which human energy turnover deviates from that of other primates remains incomplete. The recent comparison of TEE between humans and great apes [2] is influenced by the very low TEE values of orangutans, among the lowest observed in any mammal. Furthermore, the TEE data for chimpanzees and bonobos in this study showed much greater variability and imprecision than that typical of human studies, with a large difference in the mass-controlled TEE of the two ape species between two different studies [2,8].

Clearly, additional data are needed to understand the evolution of hominin energetics and its proposed link [1–3] to the peculiar life-history traits that modern humans exhibit relative to other primates. From an ecological perspective, the functioning of the brain requires continuous energy fuelling, but the majority of non-human primates inhabit, and evolved, in unpredictable seasonal environments that greatly challenge their energy strategy. Some authors have emphasized relationships between environmental unpredictability and the cognitive skills, brain organization and brain size [9,10], while others suggested that hominins may initially have evolved greater stability of energy metabolism, which subsequently allowed encephalization [11].

In this study, we use an energy intake-based approach to test the hypothesis of a substantial difference in total energy turnover between humans and non-human primates. Specifically, we address the issue of whether human traditional societies living at subsistence level have higher food intake and metabolizable energy intake for their body mass, compared with a representative set of 17 free-living non-human primate species. We also test whether these human populations have more stable energy supply year-round compared with other primates.

2. Material and methods

(a). Non-human primate data

Daily food intake data were selected from field studies undertaken since the 1970s, updated with new data (electronic supplementary material, note S1). We excluded intake data that have been pooled among adult/subadult individuals and other age classes or lactating/gestating females. We selected studies that provided an estimate of metabolizable energy intake (17 spp.; electronic supplementary material, table S1). These studies commonly assess the proportion of the different macronutrients in primate diets [12]: protein, fat, structural carbohydrates including cellulose and hemicelluloses among cell wall constituents, non-structural carbohydrates including soluble sugars and storage reserve compounds. Fibre digestibility, especially neutral detergent fibres (NDF, which include cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin), is determined in captivity for the species under investigation, or from primate models sharing similar fermenting digestive systems. In many cases, the calculation of readily digestible sugars or total non-structural carbohydrates (TNC) in the diet is estimated as the difference between 100% and the sum of all other nutrients (protein, fat, NDF, ash). We used results obtained with this mode of calculation as a first dataset for analysing the metabolizable energy input : body mass relationship across primates. We also used results of a second method for calculating metabolizable energy intake because TNC determined by subtraction potentially severely overestimates the true proportion of non-structural carbohydrates (electronic supplementary material, note S2). In the second method, we assessed the energy contribution of TNC to metabolizable energy intake based on a review of published data on the concentration of water-soluble sugars and soluble fibres in primate foods and other tropical fruits and leaves. Results from the two ways of calculating metabolizable energy intake were referred to as the ‘high energy value of the diet’ (HEVD, involving TNC determined by subtraction in the original papers) and ‘low energy value of the diet’ (LEVD, using a correction for TNC; electronic supplementary material, note S2 and tables S1 and S3). Additional information on study sites and feeding ecology of primates tested is provided in the electronic supplementary material, table S2.

(b). Human data

For consistency of comparisons and to reduce methodological heterogeneity in the evaluation of food intake, we focused on populations in which direct quantitative methods were applied. Strict methodological criteria were retained, including procedures in which foods or dishes consumed during a meal by adult men and women (above 20 years old) were weighed [13] (details in [14]). These criteria were met for five forest and savannah populations from tropical Africa (Yassa, Mvae, Bakola, Duupa and Koma) and three Nepalese populations from mid-altitude temperate areas (considered to be a single sample in the original study). Depending on the population, the diet combines farming products, natural plant resources and/or animal matter from hunting/fishing activities (electronic supplementary material, table S4). They all live at subsistence level, that is they broadly rely on self-sufficiency modes of food production/provisioning and have relatively stable energy balance in the long term (despite seasonal variations, they do not experience substantial increase in body mass throughout most of their adult lifespan, as indicated by cross-sectional measurements across wide age ranges [15]). They do not appear nutritionally deprived according to surveys of their health status and body mass index [15–17]. We discarded populations under nutritional transition from their traditional lifestyle, rural populations practicing substantial cash agriculture or populations showing excessive body mass index and inadequate energy balance. For consistency, we also did not retain studies that approximated individual daily food intake by weighing the mass of foodstuff brought to the village. Food measurements were made at three distinct seasons, and these data were averaged to avoid potential energy imbalance that may occur seasonally, often during the peak season of agriculture [18]. Metabolizable energy intake (electronic supplementary material, table S1) is calculated from classical nutritional composition tables for raw and cooked foods, as well as from complementary analyses made for specific foods when required.

(c). Data analysis

We tested which of the HEVD and LEVD models best reflected the actual amount of metabolizable energy available to primates and hence provided the most accurate set of data to be contrasted with human energy intake measurements. Specifically, we tested which of these models best equated TEE measured with doubly labelled water, the gold-standard method for measuring TEE in free-ranging animals (published data for primates and analyses in the electronic supplementary material, note S3 and table S5). The basic assumption underlying this comparison was: (i) that energy fluxes should broadly equate to a balanced energy budget, and (ii) that energy expenditure is maintained within a narrow physiological range, making it possible to use it as a reference value (as evidenced by a growing number of mammal studies [8,19,20]).

As for non-human primates, energy input estimates in humans are subject to some degree of inaccuracy. To assess data consistency, energy input was contrasted with the daily energy expenditure measured during three seasons alongside with the food intake studies on four of the populations tested (Douglas bag technique [21] in this case; published data on these populations and analyses in the electronic supplementary material, note S3 and table S5).

A phylogenetically controlled method (or phylogenetic least-squares regression) was used to assess the effect of phylogenetic relatedness in the allometric analysis of food and energy intake across species (electronic supplementary material, note S4 and figure S1).

3. Results

(a). Energy intake in non-human primates and humans

The LEVD model much more closely matched doubly labelled water measurements of TEE than the HEVD model (electronic supplementary material, note S3 and figure S2); therefore, we only focus on the former model in the subsequent analyses. Energy intake in our human sample was consistent with energy expenditure measured in parallel using time-activity-weighted indirect calorimetry, both calculated as the three-season average ([21]; electronic supplementary material, note S3 and table S5).

Plotting the non-human primate LEVD energy intake data (electronic supplementary material, table S1) against species body mass yields the following phylogenetically controlled equation:

|

where BM is the body mass. A disproportionate part (96%) of the variation of energy input was explained by body mass variation (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Results of the phylogenetic generalized least-square models testing the strength of the phylogenetic signal (λ) for various Y parameters plotted against body mass (logY = α + β logBM, with BM in g). (Best-fitting models occur where log-likelihood (Lh) is maximal. The allometric exponent (β) and coefficient (α) and their standard error (s.e.) are reported for various Lh and λ values. The proportion of the variance explained is indicated (r2). λ estimations were found to be 0 (as in ordinary least-square regressions). Figures in brackets indicate λ values forced to be equal to 1 (as in independent contrast analyses). LEVD and HEVD refer to two different primate databases for estimating energy input (Material and methods; electronic supplementary material, notes S2 and S4).)

| Y | Lh | α | s.e. (α) | β | s.e. (β) | r2 | λ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wet matter intake, g d−1 | |||||||

| non-human and human (n = 15) | −6.309 | −0.312 | 0.996 | 0.832 | 0.242 | 0.44 | [1] |

| 4.345 | 0.106 | 0.259 | 0.727 | 0.065 | 0.89 | 0 | |

| non-human (n = 14) | −5.367 | 0.151 | 0.987 | 0.717 | 0.240 | 0.39 | [1] |

| 6.463 | −0.046 | 0.225 | 0.774 | 0.057 | 0.93 | 0 | |

| dry matter intake, g d−1 | |||||||

| non-human (n = 20) | 2.766 | −0.761 | 0.520 | 0.822 | 0.129 | 0.67 | [1] |

| 13.185 | −0.467 | 0.163 | 0.740 | 0.042 | 0.94 | 0 | |

| daily energy input | |||||||

| LEVD, kJ d−1 | 1.396 | −0.151 | 0.576 | 0.896 | 0.137 | 0.72 | [1] |

| non-human (n = 17) | 14.084 | 0.412 | 0.138 | 0.749 | 0.035 | 0.96 | 0 |

| HEVD, kJ d−1 | 4.772 | 0.406 | 0.592 | 0.779 | 0.145 | 0.72 | [1] |

| non-human (n = 11) | 12.731 | 0.683 | 0.146 | 0.703 | 0.037 | 0.97 | 0 |

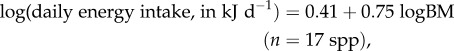

Figure 1.

Scaling of daily energy intake and TEE with species body weight in non-human primates and subsistence-level humans. Main figure: the solid orange regression line, y = 0.75(±0.04)x + 0.42(±0.15), refers to the LEVD (filled circles) database for non-human primates (averaged for each species where seasonal data or different population data are available; electronic supplementary material, table S1). The solid black line shows the scaling of TEE (measured using doubly labelled water; diamonds) with body mass in primates, y = 0.73(±0.03)x + 0.45(±0.12) (after [8]). Recent additional TEE results for apes [2] include data combined for chimpanzees and bonobos (Pan*). The average energy intake of human populations tested in this study (blue circle; n = 6) is shown. Regressions using best-fit models are derived from phylogenetically controlled analysis (table 1). The dotted lines show the 95% CI for each of the two regression lines. Box: details of human deviation from the TEE : body mass relationship (populations averaged for men and women; Y, Yassa; M, Mvae; D, Duupa; T, Nepalese; B, Bakola; K, Koma).

The data show that humans do not consume significantly more energy than other primates with similar mass. The averaged observed value for humans is 10% above the expected LEVD value (electronic supplementary material, table S5), but it clearly falls within the confidence interval (CI) of the slope (figure 1). Calculation of the 95% prediction limits of the LEVD regression for an additional datum [20,22], energy intake of humans should be greater than 79% above the predicted value to produce a significant difference (two-tailed t-test; greater than 62% with a one-tailed t-test). Similarly, with a 18% positive deviation from the TEE expected from the TEE : body mass regression published for primate species using doubly labelled water [8], the mean energy intake of the humans studied remains largely below the upper limit at 54% of the 95% prediction interval (two-tailed test) calculated for this regression line (43% with a one-tailed test).

Seasonal data available show that human populations exhibit minor variations of energy intake (median 7%, range 2–18%) relative to the nine primate species for which data are available (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Non-human primates show large seasonal variation regardless of their dietary adaptations, body size and phylogenetical relatedness (median 118%, range 0–547%). Exceptions (no variation observed) are the folivorous mountain gorillas that inhabit a relatively stable montane forest environment.

(b). Food intake in humans versus other primates

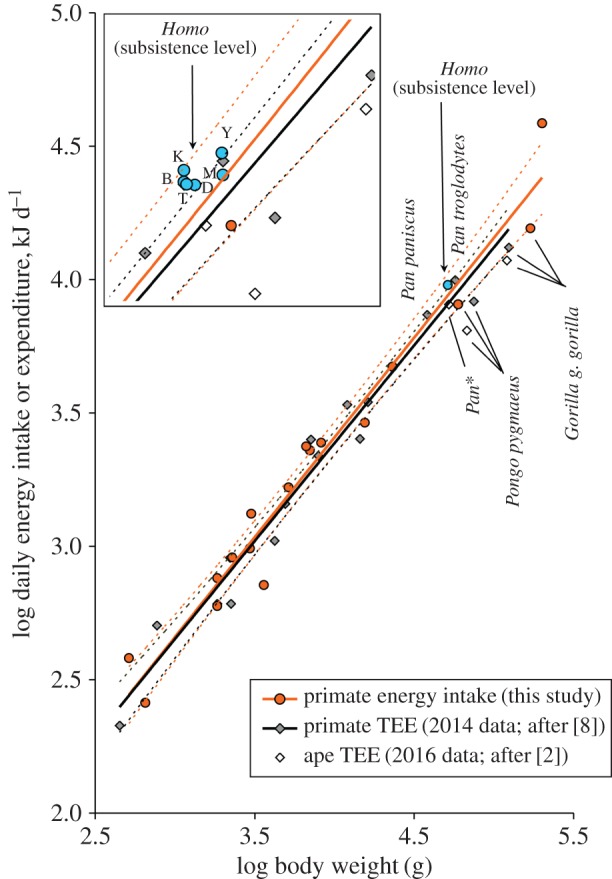

Food intake in primates including humans (averaged from six populations) follows an allometric relationship in which the equation is

according to phylogenetic least-square regression (table 1). An allometric exponent of 0.74 ± 0.16 is found using dry matter intake (database only available for non-human primates in this case; electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Each human population falls as a low outlier in the regression analysis using wet matter (with Homo residual >−3 standard deviations). Figure 2 shows, besides the phylogenetically controlled regression for non-human primates alone, daily food intakes measured in the various human populations studied. All human groups studied consistently ingest remarkably less food than predicted from their body mass, with a conspicuously low mean value of only 36 ± 6% (i.e. 2600 g less, on average) than expected in a non-human primate of the same body size. Only Propithecus coronatus consumes very little food relative to its body mass, but periods of observations were biased towards the long dry season when animals exhibited a thrifty energy strategy (reference in the electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Figure 2.

Relationship between daily food intake and body weight of primates. The regression line is calculated for free-ranging non-human primate species using the best-fit model derived from the phylogenetically controlled analysis (table 1). Human populations are figured separately. The dotted lines show the 95% CI for the regression line. (Online version in colour.)

The average energy density of the human diets (population mean ± s.d.: 6.8 ± 1.6 kJ g−1 of wet diet including raw and cooked foods) was 178% greater than that of wild non-human primates (species mean ± s.d.: 2.4 ± 0.6 kJ g−1 of wet matter).

4. Discussion

Our key finding is that, with a far more rich and energy-dense diet compared with other primates, humans consume much less food to obtain the amount of calories expected relative to their mass. At first glance, these results contradict the hypothesis that the costs of brain enlargement could be compensated by extra energy input. A recent study [2] stated that humans have 27% greater total energy expenditure relative to chimpanzees and bonobos, but, as shown in figure 1, the greater energy expenditure of humans relative to apes [2] emerges in part because the three ape species have similar (Pan) or lower TEE (Gorilla, Pongo) than predicted for their body mass. Other relatively large-brain monkeys show only moderate increase in TEE relative to the expected value (e.g. Sapajus apella; [23]), and their TEE adjusted for body mass is much smaller than that observed in several primates with a smaller brain—e.g. some small-brain species fall above the 95% confidence limits of the slope, with a deviation of 22–36% above expectations (see the grey symbols and solid black line in figure 1).

All data available therefore suggest that humans do not stand out as a major outlier in the primate data. We acknowledge that measurements of food intake have shortcomings that challenge comparisons of daily energy intake across human groups or primate species. For instance, part of the variance observed in the energy intake : body mass relationship for primates probably reflects measurement errors. In food intake surveys of humans associated with food weighing, there are inter-observer errors, and some study subjects may omit to declare the food they consumed outside their regular meals. There is also some uncertainty in the energy value of some cooked foods, and potentially large day-to-day variation in energy balance through variation in food intake and physical activity. However, this latter effect is reduced in the case of weekly monitoring [24], the method we used here. On the positive side, low costs of the method allow energy intake to be measured in larger sample sizes than usual in isotope studies and in different seasons, which collectively improves the accuracy of habitual energy turnover at the population level. Of note, our analysis of seasonal data averaged for the year showed that energy intake estimates did not differ significantly from energy expenditure measurements in the subsample we analysed (electronic supplementary material, note S3 and table S5). This suggests that any inaccuracy in our method should not markedly affect our conclusions.

In the same way, the variability around the allometric regression line drawn for energy intake does not necessarily result mainly from methodological inaccuracy but may also reflect species or population biological characteristics. We note, for example, the important variance in the scaling of primate TEE data with body mass (see above) despite the use of a rigorous method (doubly labelled water). Clearly, greater accuracy in future energy intake studies and standardization of these methods relative to isotopic studies should increase the robustness of comparative analyses.

Keeping in mind these methodological issues, our meta-analysis of primate energy intake suggests that ‘reorganization’ of the energy budget, rather than substantially increasing its total value, was probably an important step in brain evolution in the genus Homo [1,3]. There are several different ways in which such reorganization could have been achieved. First, the classic ‘expensive tissue hypothesis’ proposed that energy was diverted to the brain through reducing size of the gut [25], but this hypothesis has not been supported across mammals in general, and across primates in particular [3,26]. However, other tissues that may have traded off against the brain include muscle or liver [1,27]. The decreased cost of digestion owing to the remarkable diminution of food intake (see below) may also have contributed to the assignment of the released energy to maintaining a larger brain. Second, humans have thrifty life histories, with slow growth profiles, reducing energy demands of both juveniles and parents supporting them [28]. Third, humans may distribute energy costs socially, both overall and through cooperative breeding [29–31]. Social capital can provide ‘energy insurance’ protecting individuals from foraging failure [11]. Finally, humans may also benefit from somatic insurance, in the form of body fat stores. In contrast with social capital, body fat ring-fences energy for individual use [32]. Each of social and somatic capital can smooth over fluctuations in energy supply, reducing the need for routinely high energy intakes [33]. This generic strategy may initially have been favoured to resolve the stress of seasonality, potentially permitting the onset of encephalization in the absence of raised energy intakes [11]. Whereas subsistence human populations are able to maintain energy intake relatively stable across the year, the great seasonal variability in energy intake observed in non-human primates—possibly implying periods of negative energy balance [34–36] (electronic supplementary material, table S1)—is a telling example of the constraints imposed by natural food resources on the expansion of energy budgets.

The reduction in the quantity of food ingested to as low as 36% that of a primate with similar mass, the second main result of our study (figure 2, see also [37]), suggests that humans may have targeting foraging at energy-dense foods which in turn may have reduced the energy costs of digestion. An extensive analysis of the activity budget among primates is beyond the scope of this paper, nonetheless the total time devoted to subsistence activities in the humans tested (5 h 30 ± 1 h 00, calculated from ([21,38], P. Pasquet 1984–1988, personal observation)) is not markedly different from that spent feeding/foraging by chimpanzees, i.e. 5 h ± 1 h 30 in various habitats (and is less than that in orangutans and lowland gorillas; [39]). By contrast, the specific duration of harvesting and processing food relative to feeding time is considerable in humans. In some hunter–gatherer societies, the cost of ranging is estimated to be 31% greater than in chimpanzees owing to longer distances travelled daily and larger body mass [2,8,40].

We calculate that the increased energy costs of harvesting/processing foods (300–700 kJ d−1 according to the hunter–gatherer societies considered; electronic supplementary material, note S5) could easily be offset by lower costs of digesting smaller food volumes. In humans, digestion costs represent approximately 10% of TEE [41,42] and increase basal energy expenditure by approximately 25% [43]. On the basis of predictive equations incorporating meal size and body mass, a human consuming the reduced amount of food we report here, relative to the primate-predicted amount (−64%), would experience approximately 600 kJ d−1 lower costs of digestion (electronic supplementary material, note S5). Experimental studies on animal models with a digestive physiology similar to humans, such as pigs, indicate that further meal reductions can reduce digestion costs much more (approx. 1600 kJ d−1; [44]). We note that this energy saving could compensate for both the higher cost of foraging for energy-dense foods and for maintaining a large brain (the increased energy cost of the human brain compared with a chimpanzee is estimated at approximately 800 kJ d−1 [2]; electronic supplementary material, note S5) among other metabolically costly organs. Moreover, on an evolutionary scale, the transition from a relatively fibrous diet towards softer edible foods in the genus Homo [4] probably led to an additional decrease in the energy cost of digestion [45].

In conclusion, greater stability of energy use may have been important for human evolution, as others argued, while total energy budget does not seem to have increased to unusual proportions relative to other primates. We hypothesize that the calories saved by using readily digestible foods may have been one of the various means of reallocating energy to energy-demanding organs or costly life-history traits specific to humans. Future studies should investigate the variation of digestion costs in different nutritional contexts in humans and non-human primates to tackle this evolutionary biology issue in a more appropriate phylogenetic perspective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Laurent Tarnaud for providing plant materials for supplementary nutrient analyses on primate food; and Pierre Darlu for helping in the building of phylogenetic trees. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their help in improving the manuscript.

Data accessibility

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

B.S. designed the study, analysed data and drafted the manuscript. B.S. and S.M. contributed to new data collection in the field. All authors interpreted the data and wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version before publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), MnHn (Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle de Paris) and London Institute of Child Health.

References

- 1.Isler K, van Schaik CP. 2014. How humans evolved large brains: comparative evidence. Evol. Anthropol. 23, 65–75. ( 10.1002/evan.21403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pontzer H, et al. 2016. Metabolic acceleration and the evolution of human brain size and life history. Nature 533, 390–392. ( 10.1038/nature17654) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarrete AF, van Schaik CP, Isler K. 2011. Energetics and the evolution of human brain size. Nature 480, 91–93. ( 10.1038/nature10629) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wrangham R. 2009. Catching fire: how cooking made us human. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laden G, Wrangham R. 2005. The rise of the hominids as an adaptive shift in fallback foods: plant underground storage organs (USOs) and australopith origins. J. Hum. Evol. 49, 482–498. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmody RN, Weintraub GS, Wrangham RW. 2011. Energetic consequences of thermal and nonthermal food processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19 199–19 203. ( 10.1073/pnas.1112128108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy K, Brand-Miller J, Brown KD, Thomas MG, Copeland L. 2015. The importance of dietary carbohydrate in human evolution. Q. Rev. Biol. 90, 251–268. ( 10.1086/682587) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pontzer H, et al. 2014. Primate energy expenditure and life history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1433–1437. ( 10.1073/pnas.1316940111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sol D. 2009. Revisiting the cognitive buffer hypothesis for the evolution of large brains. Biol. Lett. 5, 130–133. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0621) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barks SK, et al. 2014. Brain organization of gorillas reflects species differences in ecology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 156, 252–262. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22646) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells JCK. 2012. Ecological volatility and human evolution: a novel perspective on life history and reproductive strategy. Evol. Anthropol. 21, 277–288. ( 10.1002/evan.21334) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman JM, Chapman CA, Van Soest PJ. 2012. Methods in primate nutritional ecology: a user's guide. Int. J. Primatol. 33, 542–566. ( 10.1007/s10764-011-9568-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koppert GJA, Hladik CM. 1990. Measuring food consumption. In Food and nutrition in the African rainforest (eds Hladik CM, Bahuchet S, de Garine I), pp. 59–61. Paris, France: UNESCO/MAB. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koppert GJA. 1996. Méthodologie de L'enquête alimentaire. In Bien manger et bien vivre. Anthropologie alimentaire et développement en Afrique intertropicale: du biologique au social (eds Froment A, de Garine I, Binam Bikoi C, Loung JF), pp. 89–98. Paris, France: ORSTOM/L'Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Froment A, Koppert GJA. 1996. État nutritionnel et sanitaire en zone de forêt et de savane au Cameroun. In Bien manger et bien vivre. Anthropologie alimentaire et développement en Afrique intertropicale: du biologique au social (eds Froment A, de Garine I, Binam Bikoi C, Loung JF), pp. 271–288. Paris, France: ORSTOM/L'Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koppert GJA, Rikong Adié H, Sajo Nana E, Tounkang P. 1997. Exploitation des écosystèmes et équilibre du milieu dans les sociétés à économie d’auto-subsistance en Afrique centrale: le cas de la plaine Tikar du Mbam (Cameroun)—Alimentation, anthropométrie et hématologie. Paris, France: ORSTOM/MINREST/MINSUP. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koppert GJA. 1993. Alimentation et croissance chez les Tamang, les Ghale et les Kami du Népal. Bull. Mém. Soc. Anthropol. Paris 5, 379–400. ( 10.3406/bmsap.1993.2369) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasquet P, Brigant L, Froment A, Koppert GA, Bard D, de Garine I, Apfelbaum M. 1992. Massive overfeeding and energy balance in men: the Guru Walla model. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 56, 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pontzer H. 2015. Energy expenditure in humans and other primates: a new synthesis. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 44, 169–187. ( 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013925) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagy KA, Girard IA, Brown TK. 1999. Energetics of free-ranging mammals, reptiles, and birds. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 19, 247–277. ( 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasquet P, Koppert GJA. 1993. Activity patterns and energy expenditure in Cameroonian tropical forest populations. In Tropical forest, people and food: biocultural interactions and applications to development. Man and the biosphere series, vol. 13 (eds Hladik CM, Hladik A, Pagezy H, Linares OF, Koppert GJA, Froment A), pp. 311–320. Paris, France: Parthenon-UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper CE, Withers PC. 2006. Numbats and aardwolves—how low is low? A re-affirmation of the need for statistical rigour in evaluating regression predictions. J. Comp. Physiol. B 176, 623–629. ( 10.1007/s00360-006-0085-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards W, Lonsdorf EV, Pontzer H.. 2017. Total energy expenditure in captive capuchins (Sapajus apella). Am. J. Primatol. 79, e22638 ( 10.1002/ajp.22638) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edholm OG, Fletcher JG, Widdowson EM, McCance RA. 1955. The energy expenditure and food intake of individual men. Br. J. Nutr. 9, 286–300. ( 10.1079/BJN19550040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aiello LC, Wheeler P. 1995. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 36, 199–221. ( 10.1086/204350) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hladik CM, Chivers DJ, Pasquet P. 1999. On diet and gut size in non-human primates and humans: is there a relationship to brain size? Curr. Anthropol. 40, 695–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard WR, Robertson ML, Snodgrass JJ, Kuzawa CW. 2003. Metabolic correlates of hominid brain evolution. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 136, 5–15. ( 10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00132-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurven M, Walker R. 2006. Energetic demand of multiple dependents and the evolution of slow human growth. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 835–841. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3380) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee PC. 1999. Comparative primate socioecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sussman RW, Garber PA, Cheverud JM. 2005. Importance of cooperation and affiliation in the evolution of primate sociality. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 128, 84–97. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20196) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hrdy SB. 2009. Mothers and others: the evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Cambridge, MA: Belknap. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells JCK. 2012. The capital economy in hominin evolution: how adipose tissue and social relationships confer phenotypic flexibility and resilience in stochastic environments. Curr. Anthropol. 53, S466–S478. ( 10.1086/667606) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells JCK. 2010. The evolutionary biology of human body fatness: thrift and control. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knott CD. 1998. Changes in orangutan caloric intake, energy balance, and ketones in response to fluctuating fruit availability. Int. J. Primatol. 19, 1061–1079. ( 10.1023/A:1020330404983) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia C, Huffman MA, Shimizu K, Speakman JR. 2011. Energetic consequences of seasonal breeding in female Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 146, 161–170. ( 10.1002/ajpa.21553) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert JE, Rothman JM. 2015. Fallback foods, optimal diets, and nutritional targets: primate responses to varying food availability and quality. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 44, 493–512. ( 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102313-025928) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barton RA. 1992. Allometry of food intake in free-ranging anthropoid primates. Folia Primatol. 58, 56–59. ( 10.1159/000156608) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasquet P, Koppert GJA, Matze M. 1996. Activités et dépenses énergétiques dans des économies de subsistance en milieu forestier et de savane montagneuse au Cameroun. In Bien manger et bien vivre. Anthropologie alimentaire et développement en Afrique Intertropicale: du biologique au social (eds Froment A, de Garine I, Binam Bikoi C, Loung JF), pp. 289–300. Paris, France: ORSTOM/L'Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masi S. 2008. Seasonal influence on foraging strategies, activity and energy budgets of western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) in Bai-Hokou, Central African Republic. PhD thesis, University of Rome La Sapienza, Rome. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Wood BM, Mabulla AZP, Racette SB, Marlowe FW. 2012. Hunter–gatherer energetics and human obesity. PLoS ONE 7, e40503 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0040503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westerterp KR, Wilson SAJ, Rolland V. 1999. Diet induced thermogenesis measured over 24 h in a respiration chamber: effect of diet composition. Int. J. Obes. 23, 287–292. ( 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinabo JL, Durnin JVGA. 1990. Thermic effect of food in man: effect of meal composition and energy content. Br. J. Nutr. 64, 37–44. ( 10.1079/BJN19900007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Secor SM. 2009. Specific dynamic action, a review of the postprandial metabolic response. J. Comp. Physiol. B 179, 1–56. ( 10.1007/s00360-008-0283-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovatto PA, Sauvant D, Noblet J, Dubois S, van Milgen J.. 2006. Effects of feed restriction and subsequent refeeding on energy utilization in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 84, 3329–3336. ( 10.2527/jas.2006-048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barboza PS, Bennett A, Lignot J-H, Mackie RI, McWhorter TJ, Secor SM, Skovgaard N, Sundset MA, Wang T. 2010. Digestive challenges for vertebrate animals: microbial diversity, cardiorespiratory coupling, and dietary specialization. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 83, 764–774. ( 10.1086/650472) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material.