Abstract

Objective

Suicide is a leading cause of death. New data indicate alarming increases in suicide death rates, yet no treatments with replicated efficacy/effectiveness exist for youths with self-harm presentations, a high-risk group for fatal and nonfatal suicide attempts. We addressed this gap by evaluating Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths (SAFETY), a cognitive-behavioral dialectical behavior therapy-informed family treatment designed to promote safety.

Method

Randomized controlled trial for adolescents (12–18) with recent (past 3 months) suicide attempts or other self-harm. Youth were randomized to SAFETY or treatment as usual enhanced by parent education and support accessing community treatment (E-TAU). Outcomes were evaluated at baseline, 3 months/end of treatment period, and followed through 6–12 months. The primary outcome was youth-reported incident suicide attempts through the 3-month follow-up.

Results

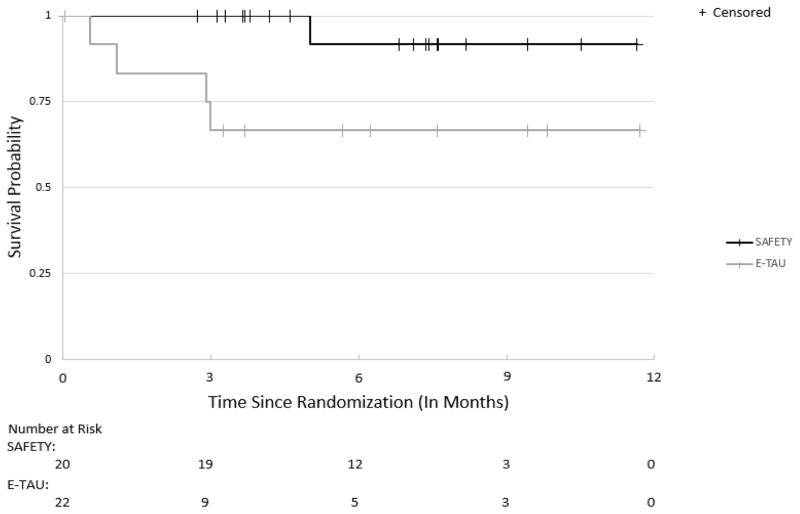

Survival analyses indicated a significantly higher probability of survival without a suicide attempt by the 3-month follow-up point among SAFETY youths (1.00, SE 0), compared to E-TAU youths ([0.67, SE 0.14], Z=2.45, p=.02, number needed to treat=3) and for the overall survival curves (Wilcoxon X2 [1]=5.81, p=.02). Sensitivity analyses using parent-report when youth-report was unavailable and conservative assumptions regarding missing data yielded similar results for 3-month outcomes.

Conclusion

Results support the efficacy of SAFETY for preventing suicide attempts in adolescents presenting with recent self-harm. This is the second randomized trial to demonstrate that treatment including cognitive-behavioral and family components can provide some protection from suicide attempt-risk in these high-risk youths.

Clinical trial registration information

Effectiveness of a Family-Based Intervention for Adolescent Suicide Attempters (The SAFETY Study); http://clinicaltrials.gov/; NCT00692302

Keywords: suicidal attempts, adolescents, treatment, self-harm, non-suicidal self-injuries

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is the second leading cause of adolescent deaths in the United States (US), responsible for more deaths than any single medical illness in youths.1 Despite strong research and clinical/public health efforts and reductions in other mortality sources, age-adjusted suicide death rates increased 24% from 1999 through 2014 (from 10.5 to 13.0 per 100,000 population). Moreover, in 2014, suicide death rates exceeded those from motor vehicle accidents among youths ages 10–14: 2.1, 425 suicide deaths versus 1.9, 384 accident deaths.1

Nonfatal suicide attempts (SAs), defined as self-directed behaviors resulting in injury or potential for injury with explicit or implicit suicidal intent, and the broader self-harm (SH) category including SAs plus undetermined SH and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI),2 are more common than suicide deaths. Prior research indicates SAs and broadly-defined SH rank among the strongest predictors of future SAs and suicide deaths, with data also indicating NSSI is a potent predictor of future SAs.3–6 Yet we still lack treatments with replicated efficacy,5,6 and analyses of community treatment as usual (TAU) suggests minimal benefits,7 underscoring the critical need to identify and test treatments for youth SAs and SH and to implement effective treatments within our health systems/communities.8

Despite limited evidence on effective treatments for adolescent SAs/SH,5 a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating treatments targeting SH found a small, statistically significant effect for tested interventions, compared to TAU/controls.6 Analyses restricted to SAs yielded non-significant effects; those restricted to NSSI mirrored results for the overall meta-analysis (just missing statistical significance), underscoring the challenges of reducing SA risk.

Currently, the interventions with the strongest RCT support for reducing adolescent SH include dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)9 and mentalization-based therapy (MBT),10 but data on SAs were not reported for either study. Based on a preliminary RCT,11 integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy (I-CBT) for youths with co-occurring suicidality and substance abuse is the only treatment demonstrating reductions in SAs. Another RCT demonstrated that multi-systemic therapy (MST, an intensive community-based treatment) with youths presenting for emergency hospitalization led to fewer SAs, compared to hospitalization12; however, the advantage for MST was not significant in youths initially presenting with suicidality.13 Developmental group therapy showed positive results on repeat SH in one RCT, relative to TAU.14 Later trials failed to replicate treatment benefits.6 Another RCT reported benefits of a parenting intervention added to TAU, compared to TAU alone, on a suicidal tendency scale.15 Promising CBT and family-centered treatments have also been evaluated using open trial/quasi-experimental designs (e.g. Treatment for Adolescent Suicide Attempters CBT, specialized emergency intervention plus cognitive-behavioral family treatment).16,17

SAFETY (Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths), a cognitive-behavioral DBT-informed family treatment aimed at reducing SA risk, has been evaluated using an open trial/quasi-experimental design.18 Grounded in social-ecological cognitive-behavioral theory, the treatment emphasizes strengthening protective supports within the family and other social systems and building skills in youths and parents that lead to safer behaviors/stress reactions.18 This emphasis on strengthening protection and healthy connections within the family and extended social ecological systems combined with CBT is consistent with the approach used in the two RCTs demonstrating significant effects on SAs.11,12 Results of our open trial supported feasibility and safety and demonstrated improved social functioning and reductions in SAs, suicidal ideation, and youth and parent depression, with medium-to-large effect sizes.18

This is a first preliminary RCT of the SAFETY program. We predicted that compared to TAU, enhanced with parent education plus support in accessing community treatment (E-TAU), SAFETY would be associated with reduced SA risk, indexed by lower probability of an SA at the end of the 3-month treatment period (primary outcome) and a correspondingly longer time to first SA. Because the strongest treatment effects were predicted at the 3-month posttreatment point, this was our primary outcome. We also explore treatment effects on NSSI, emergency department (ED) visits for suicidality, and hospitalizations for suicidality.

METHOD

All procedures were approved by the institutional review board. Youths gave written informed assent (consent if ≥ 18 years), and parents gave written informed consent. A data and safety monitoring board oversaw the study.

Participants

To obtain a sample with recent SAs/SH, participants were recruited through ED, inpatient/partial hospitalization, and outpatient services. Inclusion criteria required a recent (past 3 months) SA or NSSI as primary problem, with the additional requirement of repetitive SH, defined as ≥ 3 lifetime SH episodes. Other inclusion criteria were: age 11–18; living in stable family situation (no plans for residential placement); ≥ 1 parent willing to participate in treatment. Exclusion criteria were: symptoms interfering with participation in assessments/intervention (e.g. psychosis, substance dependence); language/not English-speaking. Recruitment occurred from: March–November 2011; August–November 2012; February 2013–May 2014; and September 2014–January 2015 (gaps due to staff/funding changes).

Randomization

Eligible participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to SAFETY or E-TAU using a computerized algorithm. To improve balance across conditions, the randomization procedure was stratified on gender and SA versus NSSI-only status at presentation. Enrollment and assessment staff were masked to randomization status.

SAFETY Program

The SAFETY program is designed to address challenges identified in treating self-harming youths. First, SAFETY is a family-centered treatment, based on the need for youth protection and demonstrated benefits of family approaches.11,12,17–19 Two therapists work with each family – one focuses primarily on the youth, the other on the parents/caregivers (hereafter referred to as parents). Sessions begin with simultaneous individual youth and parent components with their respective therapists, and conclude with all participants coming together to practice skills and address identified issues.

Second, due to the heterogeneity in pathways to SAs/SH, treatment is structured using a cognitive-behavioral fit analysis (CBFA), which identifies the chain of: triggering events; cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and environmental processes/reactions leading to the target SA/SH; and SA/SH consequences. Youth/family treatment targets are identified based on risk and protective processes identified through the CBFA, resulting in an individually tailored and principle-guided approach addressing the unique strengths and challenges of each youth/family, while also maintaining core features across participants.

Third, treatment benefits often dissipate over time, and 12 weeks may be too short to address the needs of high suicide-risk patients. Consequently, linkage to follow-up care and resources at end of treatment is a critical intervention component.

Modeled after the crisis therapy session in our emergency/ED intervention,7,17 the initial session poses a series of behavioral challenges aimed at assessing/enhancing youth’s ability to produce SA-incompatible behaviors including: recognizing/sharing personal strengths/positive attributes; identifying ≥3 persons from whom to seek support; discriminating emotional states using an “emotional thermometer” and identifying high-risk situations for SA/SH urges/behaviors; developing a SAFETY plan with concrete steps for safe coping (activities, thoughts, behaviors) and a SAFETY card/screenshot to prompt/guide safe responses; and committing to using the SAFETY plan versus SA/SH for a specified period, at least until the next appointment. Psychoeducation was provided on the importance of restricting access to dangerous SA/SH methods and the risks of disinhibition associated with substance use. Parents were counseled regarding the need for protective support, connectedness, and monitoring, and to promote generalization, youths practiced using the SAFETY plan, with parents present (unless counter-indicated).

To reduce barriers to treatment attendance and strengthen understanding of the home/community environment, this session was conducted in families’ homes. Therapists brought a lock-box and worked individually with parents and youths encouraging them to lock up/remove potentially dangerous SA/SH methods (e.g. medications). Time was spent with youth alone, parents alone, and all together, allowing flexibility to ensure optimal completion of session tasks.

The CBFA was formulated, further developed throughout subsequent sessions, and used to develop a collaborative treatment plan that considered youth and parent perspectives/preferences and specified the treatment modules used. The treatment plan was organized around a SAFETY pyramid emphasizing: 1) SAFE SETTINGS (the pyramid base)–restricting access to dangerous SA methods and attending to risk and protective factors across key settings (home, school, peer, community); 2) strengthening interactions with SAFE PEOPLE; 3) encouraging SAFE ACTIVITIES AND ACTIONS; 4) SAFE THOUGHTS; and 5) SAFE STRESS REACTIONS. Modules emphasized skills from CBT, DBT, and family-centered approaches.7,9,17,18,20,21 Frequently used modules for youths were: developing a “hope box” filled with reminders of reasons for living and cues/facilitators of the safety plan; activity scheduling; helpful thoughts; problem-solving; emotion regulation; distress tolerance; and understanding depression and emotional spirals. Skills emphasized with parents included: active listening/validation; communication; problem-solving; parent safety plan; education about depression/emotional regulation; self-care; and developing a family album.

Subsequent sessions were in the clinic. Standard session format included: agenda setting; bridging to prior session; safety check; practice/homework review; work on session-specific skill or topic; addressing youth/parent-identified issues; review/updating SAFETY plan; and practice assignments. Therapists worked as a team, jointly selecting session foci. When SA/SH urges/behaviors were reported, the therapist quickly communicated this to the other therapist to ensure safety issues were addressed with youth and parents. Practices/homework included: a mood monitoring/diary card for youths, designed to provide a regular safety check and focus youths on identifying/using strategies/skills for safe, effective coping; and practices to reinforce skills emphasized in session.

The final family-session component brought youths, parents, and therapists together to practice using “safety skills/behaviors,” with the goals of enhancing generalization and the likelihood that youths would turn to their parents at high-risk times. The family session agenda included: 1) “thanks notes,” an exercise designed to enhance family support and communication, with each participant giving short thanks notes expressing something they appreciated about each family member (e.g. “thanks for listening”); 2) capsule summaries where youths and parents shared what they worked on during individual session components, providing opportunities for skill consolidation/generalization; 3) practicing a specific skill/discussing an issue; and 4) assigning family practices, including giving family thanks notes, and sometimes other skills.

The final three weeks of treatment emphasized skill consolidation, relapse prevention, and linkage to needed services. Because most youths have access to primary care services, this plan always included connections to primary care. If desired and indicated, youths were also linked to mental health, school-based, and/or other community services.

Enhanced TAU

The E-TAU condition aimed to increase youth safety and enhance linkage to outpatient treatment. E-TAU included an in-clinic parent session, followed by ≤3 telephone calls aimed at supporting motivation/actions to obtain follow-up treatment. Consistent with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Practice Parameters,22 therapists educated parents about the risk of repeat SA/SH behavior, steps to reduce risk (restrict access to dangerous SA/SH methods, protective monitoring/support, danger associated with disinhibiting effects of alcohol/drug use), and importance of follow-up care, and worked with parents to develop plans for maintaining youth safety and establishing follow-up treatment. Modeled after the parent telephone calls in Spirito et al.’s compliance enhancement intervention,23 calls included a check on youth’s mood, safety, outpatient treatment attendance, barriers to beginning/continuing treatment, and work to enhance motivation and address treatment-attendance barriers. Calls were scheduled for roughly one week after the in-person session, two weeks after the first call, and four weeks after the second call, with calls stopping when youths were attending treatment regularly.

Treatment Adherence

SAFETY

Youth sessions were rated (J.A., J.L.H.) for CBT adherence using the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS) and parent/family sessions for adherence to MST principles using the MST Therapist Adherence Measure-Revised (TAM-R).18 Ratings on roughly a third of randomly selected sessions revealed excellent adherence: 100% of CTRS ratings exceeded the CTRS adherence score of 40 (mean 63.74, SD 4.41)24; MST adherence ratings indicated that MST principles were generally rated as present (adherence score ≥4): Mean 4.76, SD 0.25. Parent-rated MST adherence ratings at mid-treatment (6 weeks) and end of treatment (12 weeks) also indicated strong MST adherence: mid-treatment Mean 4.34, SD 0.45; end of treatment Mean 4.46, SD 0.39.

E-TAU

E-TAU adherence was rated for the presence of 13 treatment components (e.g. psycho-education on SA risk factors, steps to reduce risk, importance of follow-up treatment) using a 3-point scale (1 = clearly present, 3 = not present). Ratings on roughly a third of randomly selected sessions indicated strong adherence, mean item score 1.05, SD 0.08.

Assessment

Following brief screening, baseline assessments with youths and parents determined eligibility. Posttreatment assessments were conducted at roughly 3 and 6 months after baseline, with the 6-month assessment window remaining open through 12 months postbaseline. Assessments were conducted in person, with briefer telephone evaluations done when there were difficulties scheduling in-person visits. Assessment staff were naive to treatment condition. Parent assessments were conducted with the identified primary caretaking parent (usually mothers).

Measures

SAs/SH were assessed using a slight modification of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), which contains probes/scales for rating severity of suicidal behavior plus a parallel scale assessing NSSI, and the Suicide History Interview, which provided information on dates, classification (SA vs. NSSI), methods, and lethality of all SA/SH episodes.18,25 Because youths are considered the best reporters of internal states such as intent to die,26 youth self-report was used in primary analyses of SA/SH outcomes. The mood and psychosis modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and Adolescents (NIMH DISC IV) assessed diagnoses. This structured computer-assisted interview designed for lay-interviewer administration has demonstrated adequate reliability.27 Quality assurance monitoring by a senior staff member trained by the DISC development team on 20% of randomly selected interviews indicated strong quality (Mean =1.2, SD=0.54, 3-point scale 1=good to 3=poor). The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA), adapted for youths presenting with suicidality/self-harm,7 provided parent-reported information about ED visits, hospitalizations, and other services. Research documents high agreement between parent and youth report on the SACA.7,28 Demographic information was assessed through youth (age, gender, race, ethnicity) and parent report (income, health insurance). Youth and parent past-week depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D), a psychometrically adequate adolescent and adult depression measure. The Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI)29 assessed youth substance abuse. Youth externalizing (e.g. stealing, aggression) and internalizing symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety) were assessed using the Youth Self-Report (YSR) and parent-report (Child Behavior Checklist, CBCL). These empirically-based measures yield standardized scores based on national norms and provide an indication of clinical significance.30

Statistical Analysis

Primary analyses were intent to treat, incorporating data from all participants regardless of degree of participation. Outcomes were evaluated using survival analytic techniques to account for censoring. Nonparametric Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival functions were used to characterize the probability of the event of interest (SA, NSSI, ED, hospitalization) over time for each group, and between-group differences in survival curves were evaluated. In this small first RCT, the 3-month posttreatment point, defined as 91 days postbaseline, was our primary outcome point. We also compared groups over the entire assessment interval to check for overall differences in timing of events. Because the strongest intervention effects were predicted during and immediately posttreatment, we used both the Wilcoxon test, a nonparametric rank-based procedure that more heavily weights earlier events in the survival distribution, and the log-rank test, which weights all timepoints evenly. Length of follow-up for each participant was represented by the number of days between the date of the baseline assessment and either the date of the event-of-interest or last assessment, whichever came first. Youth report was used in our primary SA and NSSI analyses. Sensitivity analyses were performed, first by using parent report when youth report was unavailable, and then by adopting conservative assumptions regarding participants who dropped out early. While standard survival models assume that censoring is non-informative so that censored individuals will have the same time-to-event distribution as non-censored participants, more severely ill participants could have been more likely to remain in the study, which, given the higher attrition rate among E-TAU youths, could bias results in favor of SAFETY. We therefore fit a much more conservative model, assuming that all E-TAU youths lost to follow-up before 3 months were “SA free” and uncensored through 3 months, the strictest primary treatment comparison.

We report standard descriptive statistics and estimate intervention parameters such as attrition rates, event rates, and number needed to treat (NNT) to inform the design of future studies. Analyses used SAS, Version 9.4 (copyright 2013, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Statistical Power

This study aimed to obtain preliminary data for designing a larger-scale evaluation. With the proposed n=30/group, α=.05 and an expected SA rate of 30–40% in E-TAU, the SA rate in SAFETY would need to be 4–10% to yield 80% power. Because additional time was needed for treatment development, we were unable to reach this recruitment target.

RESULTS

We screened 140 youths whose parents expressed interest in RCT participation, consented 53 potentially eligible youths, completed baseline assessments on 49, and excluded 7, resulting in 42 youths in the randomized intent-to-treat sample: SAFETY (n=20); E-TAU (n=22) (Figure 1). Enrolled youths were referred from EDs (n=5), inpatient/partial hospital programs (n=17), outpatient services (n=18), and schools (n=2). Most youths (28/42, 67%) had recent ED visits and/or hospitalizations. At baseline, youths averaged 14.62 years of age, were 88.1% female, and varied in ethnicity, race, and income (Table 1). Lesbian, gay, or bisexual orientation was reported by 21.5% of youths. Half the sample reported SAs, and half reported NSSI-only within the preceding 3 months. Lifetime SAs were reported by 66.7% of youths, 21.4% reported multiple SAs, 88.1% reported lifetime SH, and 57.1% reported both lifetime SAs and NSSI. Hospitalizations and ED visits (past 3 months) were reported by 50.0% and 64.3% of youths respectively, 54.8% met past-year DISC major depressive disorder (MDD) criteria, and 61.9% reported severe past-week depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥ 24). Youths presented with a range of symptoms/problems including substance use and externalizing behavior (Table 1). Clinically elevated depressive symptoms were reported in 52.4% of primary caretaking parents (mostly mothers, 85.7%). SAFETY and E-TAU youths were similar on demographic and clinical variables, with no statistically significant between-group differences.

Figure 1.

Participant flow. Note: NSSI = non-suicidal self-injury; SA = suicide attempt; SAFETY = Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths. aUnstable living situation, n = 13; psychosis, n = 3; substance abuse, n = 2; language, n = 2; age, n = 5; medical condition, n = 1; left emergency department/unit, n = 11; unknown/not reachable, n = 11. b n = 6 based on early report, within first 30 days.

Table 1.

Sample Description at Baseline

| Overall (N=42) | SAFETY (n=20) | Enhanced TAU (n=22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

|

| |||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 14.62±1.83 | 14.35±1.81 | 14.86±1.86 |

| Female | 37 (88.1%) | 18 (90.0%) | 19 (86.4%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 35 (83.3%) | 18 (90.0%) | 17 (77.3%) |

| Black | 2 (4.8%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.6%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9 (21.4%) | 4 (20.0%) | 5 (22.7%) |

| Asian | 5 (11.9%) | 1 (5.0%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| Other | 3 (7.1%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (9.1%) |

| Family annual income | |||

| $15,000 to $29,999 | 5 (11.9%) | 2 (10.0%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 5 (11.9%) | 3 (15.0%) | 2 (9.1%) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 7 (16.7%) | 5 (25.0%) | 2 (9.1%) |

|

| |||

| Clinical Variables | |||

|

| |||

| SA, past 3 months | 21 (50.0%) | 10 (50.0%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| Nonsuicidal self-injury, past 3 months | 21 (50.0%) | 10 (50.0%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| >1 Lifetime SA | 9 (21.4%) | 4 (20.0%) | 5 (22.7%) |

| Major depression, past year | 21 (54.8%) | 8 (40.0%) | 15 (68.2%) |

| Problematic substance use | 20 (47.6%) | 10 (50.0%) | 10 (45.5%) |

| Youth Self-Report | |||

| Externalizing behavior, clinical range | 13 (30.95%) | 7 (35.0%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| Internalizing behavior, clinical range | 30 (71.7%) | 13 (65.0%) | 17 (77.3%) |

| Parent Child Behavior Checklist | |||

| Externalizing behavior, clinical range | 16 (38.1%) | 5 (25.0%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| Internalizing behavior, clinical range | 30 (71.7%) | 13 (65.0%) | 17 (77.3%) |

Note: SA = suicide attempt; SAFETY = Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths; TAU = treatment as usual.

Treatment Received

SAFETY

SAFETY youths received a mean of 9.90 sessions (SD=2.95), over a range of 82.7 days (SD=20.22). Number of sessions ranged from 3–15; 70% received 9–12 sessions (3–7, n=4; 14–15, n=2). All families had a home visit.

E-TAU

All but one youth (95.5%) received in-person parent sessions, with a mean of 1.56 follow-up calls (SD 0.78, range: 0–3). Based on follow-up calls, 81.8% were in treatment at the last call.

Attrition

Survival analyses provided an ITT comparison of event rates over time, appropriately accounting for censoring. We used sensitivity analyses to confirm whether findings were robust to conservative assumptions regarding participants lost to follow-up. These conservative analyses were important due to the different patterns of censoring across conditions. While data were available for 100% of the sample using any report, youth-report data were available for 55% of E-TAU youths vs. 100% of SAFETY youths. Any report data for 6 E-TAU youths were obtained early (within first 30 days).

SA Outcomes

At 3 months/posttreatment, four youths had made SAs; two made single attempts (1 overdose, 1 jumping from high place), another made an SA (hanging) plus interrupted attempt (electrocution), and another made three attempts (2 overdoses, 1 hanging). This resulted in a total of six SAs, all in the E-TAU condition. Three of the four youths making SAs also reported ≥ one NSSI incident.

Two additional youths engaged in preparatory behavior but did not initiate SAs (1 E-TAU; 1 SAFETY). At about 5 months postbaseline, one SAFETY youth who had reported preparatory SA behavior at 3 months reported an SA (overdose).

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan Meier estimates of the survival curves for time to first youth-reported SA. While no SAFETY youths made SAs by 3 months, E-TAU youths had a cumulative estimated probability of SA survival of 0.67 (SE 0.14), a significant between-group difference at this primary outcome point (Z = 2.45; p = .01, NNT=3.0). Comparison of overall survival curves showed a significant difference favoring the SAFETY condition, both by the Wilcoxon (χ2[1] =5.81, p=.02) and Log-Rank tests (χ2 [1]=4.564, p=.04), with results driven by the early part of the study window. Sensitivity analyses using parent report when youth report was unavailable yielded similar results, with a statistically significant group difference at the 3-month point (Z=2.27, p=.02, NNT=4.17), and the comparison of the overall survival curves just missing statistical significance (Wilcoxon χ2[1]=3.33, p=.07, Log-Rank χ2[1]=2.88, p=.09). Additional sensitivity analyses assuming that all E-TAU youths who dropped out early reached the 3-month time point SA-free also yielded comparable results, with a significant difference at the end of acute treatment (Z=2.09, p=.04, NNT= 4.35) and just missing significance in the overall survival curves (Wilcoxon χ2[1]=3.4956, p=.06, Log-Rank χ2[1]=2.71, p=.099).

Figure 2.

Probability of survival without a suicide attempt. Note: E-TAU = enhanced treatment as usual; SAFETY = Safe Alternatives for Teens and Youths.

NSSI

NSSI was frequent across groups; estimated probabilities of survival without an NSSI episode by 3 months were 0.55 (SE 0.11) for SAFETY and 0.43 (SE 0.14) for E-TAU. Survival analyses evaluating time to first NSSI event yielded a non-significant group difference at the 3-month assessment point (Z=0.64, p=.524, NNT=8.33), and for the overall curves (Wilcoxon χ2[1]=0.07, p=.797, Log Rank χ2[1]=.037, p=.846).

Suicide-Related ED Visits and Hospitalizations

The probability of survival to the 3-month posttreatment point without an ED visit for suicidality was significantly lower for E-TAU (0.71, SE 0.11) compared to SAFETY youths (0.90, S E 0.07, Z=2.00, p=.045, NNT = 5.26). Because all these ED visits led to hospitalizations, survival analyses evaluating time to suicide-related hospitalizations yielded identical results. The overall difference in the survival functions for ED visits was significant using the Log Rank test (χ2 [1]=3.89, p=.049); marginal with the Wilcoxon test (χ2[1]=3.20, p=.074); and in conservative sensitivity analyses (Z=1.80, p=.071, overall Log-Rank test χ2[1]= 2.94, p=.086, Wilcoxon χ2[1]= 2.23 [1], p=.135), and not statistically significant for hospitalizations.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present results provide only the second RCT demonstrating the efficacy of a psychosocial treatment for reducing SA risk among youths with recent SAs/SH. When compared to E-TAU, the SAFETY treatment lowered the probability of an SA (lengthened the SA-free survival time), with no SAs in the SAFETY condition and an estimated SA-risk of 0.33 in the E-TAU group at the 3-month follow-up point. The NNT estimate suggests that treating roughly three youths with SAFETY could prevent one SA. These data combined with those from the I-CBT RCT11 demonstrate that psychosocial treatments can reduce SA risk in these youth with elevated risk for fatal and nonfatal SAs.

Both SAFETY and I-CBT11 combined strong family and CBT interventions. While adolescence is a period when youths’ focus shifts to peers, brain regions in areas responsible for planning and inhibitory control are still developing, and parents/other adults can play key protective roles.31 Restricting access to dangerous SH methods and protective monitoring/support can offer some protection when adolescents experience intense emotional distress and SH urges (like seatbelts). This was a primary goal of the SAFETY treatment, which aimed to strengthen parents’ abilities to protect and support their children’s and youths’ abilities to accept support and protection.

Study results underscore the longer-term and possibly chronic risk among self-harming youths. While SAFETY appeared to protect against SAs during the treatment period, benefits weakened after treatment ended, suggesting the need for longer and/or continuation and maintenance treatments. It merits note that I-CBT11 was 12 months in duration, DBT, which has demonstrated efficacy for reducing SAs in adults, is a 12-month treatment,20 and CBT for suicidal adults includes 10 sessions delivered over a variable time interval until patients successfully complete a relapse prevention task.21

Our 3-month treatment period was selected with guidance from community partners for feasibility within emergency services. Among SAFETY youths, there was only one SA between 3–6 months, and this youth had shown preparatory SA behavior during the treatment period. An approach, therefore, that evaluates risk at end of acute treatment and triages youth using stepped-care algorithms to more or less intense services based on assessed need could provide one strategy for addressing more chronic risk.

Contrasting with results from other trials,6,9,10 results were strong for SA but weaker for NSSI outcomes. While results suggested an advantage for SAFETY, power was weak, and between-group differences were not statistically significant. A longer and/or more intensive treatment period may be required to alleviate this often-entrenched behavior pattern, such as that provided in DBT (weekly psychotherapy, 2-hour skills training groups, and as-needed phone coaching).

Study results indicate that E-TAU was a non-optimal comparator, with high attrition, particularly for youth assessments. Despite this study limitation, the survival analyses considered all available data, taking censoring into account, and primary results (group comparison of SAs at end of acute treatment) were robust even to the most conservative assumptions about participants who dropped out. Ethically, the E-TAU condition was chosen based on the known need to improve linkage to follow-up treatment8,17 and desire to link youths to the best available community care without restrictions. Indeed, 81.8% of E-TAU youths were successfully linked to treatment. Identifying an optimal comparator condition for high SA-risk youths is challenging given other reports of differential attrition and reluctance to accept randomization,16 underscoring the potential value of using strong active comparators and alternatives to classical RCTs.32,33

Another study limitation is the small sample/limited statistical power. Replication and larger studies are needed to confirm study findings. Consistent with the higher SA rates in females and samples in trials recruiting suicide-attempting youths primarily through mental health services,11,16,18 the sample was mostly female, limiting data on males, a group with higher suicide death risk. Alternative approaches to identifying high suicide-risk males are needed, perhaps including indicators other than SAs, which are more common in females, or recruiting through non-mental health sites (e.g. juvenile justice). Because the study used a single site, results may not generalize more broadly, although the sample was relatively diverse in ethnic and racial composition given the geographic location. The sample was underpowered to compare treatment effects among youths with recent SAs versus NSSI; future research is needed to clarify optimal criteria for determining need for intense SH-focused treatments such as SAFETY. Although group differences were not statistically significant, some symptom measures were somewhat higher in E-TAU youths, which could have contributed to observed effects. Intensity of the study treatments also varied. For this first RCT, we chose to exclude youths with psychosis and substance abuse/dependence. As expected given the frequent co-occurrence of suicidal behavior and substance use, nearly half of youths endorsed some problematic use. Consistent with the SAFETY approach of individually tailoring treatment modules to address the heterogeneity in pathways to SAs/SH, future work might develop strategies for addressing the needs of a broader population of youths with SAs/SH.

Study results provide evidence that SAFETY, a DBT-informed cognitive-behavioral family intervention, is beneficial for treating youth presenting with SAs/SH. In conclusion, the present results support the safety and efficacy of the SAFETY treatment for reducing SA risk among youths presenting with SA/SH episodes. Future research is needed to further evaluate efficacy, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness. The value of SAFETY might be enhanced by including continuation and/or maintenance treatment strategies to address longer-term risk in this population, and incorporating algorithms and treatment strategies/modules to meet the needs of the broader SA/SH population, including those with substance abuse/dependence and psychosis.

Clinical Guidance.

Study results provide evidence that SAFETY, a DBT-informed cognitive-behavioral family intervention, is beneficial for treating youth presenting with SAs/SH.

Strengthening bonds and feelings of connectedness between youths and their parents or other responsible figures can provide protection, like seatbelts, when youths experience suicidal impulses or urges.

Enhancing parent and youth communication skills enables youths to accept protection and builds hope in parents that they can successfully guide their children through suicidal/self-harm episodes as well as hope in youths that their parents can help them through what feels like unbearable pain and unsolvable problems.

Teaching skills for regulating emotions, tolerating distress, building lives that youths want to live, and addressing mental health and psychosocial problems are key treatment components.

Assessment of the unique risk and protective processes for each youth/family and tailoring of intervention targets/modules provides an alternative to a one-size-fits-all approach to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH078082) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). The funding agencies have no involvement in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Dr. Sugar served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors wish to thank the youth, families, staff, and colleagues who made this project possible, including members of the Data Safety and Management Board: Donald Guthrie, PhD, Retired, Seattle, Washington; Gabrielle Carlson, MD, of SUNY at Stony Brook; and Mark Rapaport, MD, of Emory University.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Asarnow has received grant or research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the American Psychological Association (APA) Committee on Division/APA Relations, and the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Division 53 of the APA). She has served as a consultant on quality improvement interventions for depression and suicidal/self-harm behavior. Dr. Hughes has received grant or research support from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. She has served as a consultant on quality improvement interventions for depression and suicidal/self-harm behavior in youth. Dr. Sugar has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through multiple divisions including the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); the US Department of Veterans Affairs; and the John Templeton Foundation. She has served on technical expert panels for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Data Safety and Monitoring Boards for both academic institutions and Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Babeva reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Joan Rosenbaum Asarnow, University of California Los Angeles School of Medicine, Los Angeles.

Dr. Jennifer L. Hughes, Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care (CDRCC), University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dallas.

Dr. Kalina N. Babeva, University of California Los Angeles School of Medicine, Los Angeles.

Dr. Catherine A. Sugar, University of California Los Angeles School of Medicine, Los Angeles.

References

- 1.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. [Accessed March 3, 2017];NCHS Data Brief. 2016 (241) http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6543a8. [PubMed]

- 2.Crosby AE, Ortega L, Melanson C. Self-directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, Goldstein TR, Mayes TL, Douaihy AB. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: A critical review of intervention studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(12):1260–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):97–107. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1303–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: Author; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: A randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(10):1082–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A, Kahler CW, Hunt J, Monti P. Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: A randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:728–739. doi: 10.1037/a0026074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, et al. Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:183–190. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Pickrel SG. Predictors of treatment response for suicidal youth referred for emergency psychiatric hospitalization. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34:582–589. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood A, Trainor G, Rothwell J, Moore A, Harrington R. Randomized trial of group therapy for repeated deliberate self-harm in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1246–1253. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineda J, Dadds MR. Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: A randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brent D, Greenhill L, Compton S, et al. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters (TASA) Study: Predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Piacentini J, Cantwell C, Belin TR, Song J. The 18-month impact of an emergency room intervention for adolescent female suicide attempters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:1081–1093. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asarnow JR, Berk M, Hughes JL, Anderson NL. The SAFETY Program: A treatment-development trial of a cognitive-behavioral family treatment for adolescent suicide attempters. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:194–203. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.940624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:563–570. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaffer D, Pfeffer CR, Bernet W, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:24S– 51S. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D, Bishop D, Lewander W. An intervention trial to improve adherence to community treatment by adolescents after a suicide attempt. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brent DA, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901–913. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berk MS, Asarnow JR. Assessment of suicidal youth in the emergency department. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2015;45:345–359. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, et al. The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1032–1039. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200008000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Tarter R. Norms and sensitivity of the adolescent version of the drug use screening inventory. Addict Behav. 1995;20:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Form and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet (London, England) 2016;387:2423–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cwik MF, Walkup JT. Can randomized controlled trials be done with suicidal youths? Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:177–182. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson JL, Stanley B, King CA, Fisher CB. Intervention research with persons at high risk for suicidality: Safety and ethical considerations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(SUPPL 25):17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]