Abstract

Mitochondrial dynamics and quality control plays a critical role in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis and function. Pathogenic mutations of many genes associated with familial Parkinson’s disease (PD) caused abnormal mitochondrial dynamics, suggesting a likely involvement of disturbed mitochondrial fission/fusion in the pathogenesis of PD. In this study, we focused on the potential role of mitochondrial fission/fusion in idiopathic PD patients and in neuronal cells and animals exposed to paraquat (PQ), a commonly used herbicide and PD-related neurotoxin, as models for idiopathic PD. Significantly increased expression of dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1) and a trend towards reduced expression of Mfn1 and Mfn2 were noted in the substantia nigra tissues from idiopathic PD cases. Interestingly, PQ treatment led to a similar changes in the expression of fission/fusion proteins both in vitro and in vivo which was accompanied by extensive mitochondrial fragmentation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Blockage of PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation by Mfn2 overexpression protected neurons against PQ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro. More importantly, PQ-induced oxidative damage and stress signaling as well as selective loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra and axonal terminals in striatum was also inhibited in transgenic mice overexpressing hMfn2. Overall, our study demonstrated that disturbed mitochondrial dynamics mediates PQ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and neurotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo and is also likely involved in the pathogenesis of idiopathic PD which make them a promising therapeutic target for PD treatment.

Keywords: mitochondrial dynamics, DLP1, Drp1, Mfn2, paraquat, Parkinson’s disease

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease and affects as many as one million Americans. Rest tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and loss of postural reflexes are cardinal clinical signs of the disease [1]. PD is characterized by selective loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SN) region of the midbrain and accumulation of Lewy bodies comprised principally of misfolded α-synuclein in the surviving neurons. Only a small fraction of PD patients report a positive family history, and about 95% of PD cases are idiopathic during which environmental factors must play an important role in the pathogenesis [2]. Epidemiological studies found that rural living, farming as an occupation, drinking well water, and pesticide/herbicide exposure, each were associated with an increased risk for developing PD [3–5]. Among various pesticides/herbicides that may be involved, paraquat (PQ) is more clearly indicated since it is associated with two-fold increased risk for PD [6, 7] and more importantly, there are known cases of PD directly linked to PQ toxicity [8]. Paraquat is an herbicide that is structurally similar to the active metabolite form of neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and accumulates in DA neurons in the monovalent cation form [9]. It is a very efficient redox cycling compound that likely exerts its deleterious effects through oxidative stress. Treatment of rodents with PQ successfully replicates some of the key features of PD including DA neuronal loss in the SN region, α-synuclein aggregates, and motor behavioral deficits, etc. [10, 11], and is a widely used model to study environmental contribution to the development of PD.

Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a critical event during the pathogenesis of PD, although the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles with the ability to continuously fuse and divide so as to maintain the shape, number and proper distribution of mitochondria, which plays a critical role in the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis and function that is essential to neuronal function and survival. Mitochondrial dynamics is regulated by several large GTPases including mitofusin 1/2 (Mfn1/2) and optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) on the fusion side, and dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1) on the fission side assisted by mitochondrial outer membrane receptors such as mitochondrial fission 1 (Fis1) and mitochondrial fission factor (Mff) [12–15]. Disturbed mitochondrial dynamics are implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple neurological diseases [16]. Notably, multiple lines of evidence suggested that proteins encoded by previously identified genes associated with familial PD are localized to mitochondria and involved in the regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and homeostasis: PINK1, a Ser/Thr kinase located on mitochondrial outer membrane, senses mitochondrial functional state and acts in cooperation with Parkin to mark damaged mitochondria for disposal, a process that involves interactions/modifications with fission/fusion factors and interconnects with and impacts mitochondrial dynamics [17–19]; α-synuclein causes mitochondrial fragmentation by enhancing mitochondrial DLP1 translocation either through ERK pathway [20] or by directly binding to and inhibiting membrane fusion which could be rescued by PINK1/Parkin/DJ-1 [21]; LRRK2, VPS35 and DJ-1 impact mitochondrial dynamics by interacting with the mitochondrial fission machinery [22–24]. Therefore, it is clear that an altered balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion plays a critical role in mitochondrial dysfunction and pathogenesis of familial PD associated with these genes.

In the current study we aimed to determine whether a tipped balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion also occurs in idiopathic PD by investigating the expressional change of mitochondrial fusion/fission proteins in the SN tissues from idiopathic PD patients and exploring the cause-effect relationship between disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death in PQ treatment-based in vitro and in vivo models of idiopathic PD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cell culture and transfection

The human dopaminergic neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (Human, Female, 4 years. ATCC® CRL-2266) were grown in Opti-MEM I medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 31985088), supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, 10438026) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, 15140122). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 11668019) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primary neurons from E18 rat cortex (BrainBits, Springfield, IL) were seeded at 30 000–40 000 cells per well on 8-well chamber slides coated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, P6407) in neurobasal medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, 21103049) supplemented with 2% B27/0.5 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, 17504044/25030081). Half the culture medium was changed every 3 days. All cultures were kept at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2-containing atmosphere. More than 90% of the cells were neurons after they were cultured for seven DIV, which was verified by positive staining for the neuronal-specific markers microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2, dendritic marker). At DIV5, primary cortical neurons were transfected using NeuroMag transfection reagent (OZ Biosciences, San Diego, CA, NM51000) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For co-transfection, a 9:1 (Myc-Mfn2: mitoDsRed2/GFP) was applied.

2.2 Expression vectors, antibodies, chemicals, and measurements

MitoDsRed2 construct (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, 632421) were obtained and stored in the lab. The expression plasmid for myc-tagged Mfn2 were constructed based on the pCMV-Tag3 Vector (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, 211173). Thy1.2-hMfn2 construct was based on a modified mouse Thy1.2 promoter cassette [25]. Antibodies used in this study included mouse anti-Myc epitope tag antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, MA1-21316), mouse anti-DLP1/OPA1 (BD, San Jose, CA, 611112/612606), mouse anti-Mfn1/Mfn2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, sc-50330/ sc-100560), mouse anti-β-Actin (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 12262), mouse anti-TH (Millipore, Temecula, CA, MAB318), rabbit anti-MFF (Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, 17090-1-AP), rabbit anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 2118), rabbit anti-4-HNE (Alpha diagnostics, San Antonio, TX, HNE11-S), rabbit anti-MAP2 (Millopore, Millipore, Temecula, CA, AB5622), rabbit anti-pJNK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 9251), anti-mouse/rabbit HRP-linked secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 7076 or 7074), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Life technologies, Eugene, OR, A21202). Paraquat (PQ) dichloride hydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 856177) was purchased and dissolved in culture medium for cell treatment. MitoSOX and TMRM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, M36008/T668) were used to analyze mitochondrial superoxide production and mitochondrial membrane potential according to manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3 Animals and treatment

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Case Western Reserve University. Selective human Mfn2 overexpression in mice neurons was achieved under the control of Thy-1.2 promoter. The hMfn2 transgenic (Tg) mice were maintained under constant environmental conditions in the Animal Research Center of Case Western Reserve University with free access to food and water. The development of hMfn2 Tg mice appeared normal compared with the non-Tg littermates. Male 12-week old non-Tg mice (n=23) and heterozygous hMfn2 Tg mice (n=29) were used in all of the experiments. PQ administered to the animals were dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline and injected intraperitoneally. hMfn2 Tg mice and nontransgenic littermate controls received either a dose of 10 mg/kg PQ twice a week for 4 consecutive weeks an equal volume of vehicle. 7 days after final injection, mice were sacrificed for tissue collection. Half brains were fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry. Substantia nigra and striatal tissues were dissected from the other half brains for western blot analysis.

2.4 Western blot analysis

Human midbrain tissue samples were collected at time of autopsy and stored at −80°C. Samples were obtained from the University Hospital Case Medical Center under an approved IRB protocol or from the Harvard Brain Bank through the Neurobiobank program. For this study, a small area of the substantia nigra from PD patients (n=4, one female and three males) and age-matched control patients (n=4, one female and three males) was carefully dissected out and homogenized with RIPA lysis buffer plus protease inhibitor mixture (Roche, Penzberg, Germany, 5892791001/4906837001). There are no significant difference in the age and post mortem interval between PD cases (78.5 ± 11.7 years; 14.0 ± 6.7 hours) and controls (80.5 ± 5.1; 17.5 ± 4.4). Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatants collected and protein level determined using BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, 23225). Equal amounts of total protein extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore, Temecula, CA, IPVH00010). Following blocking with 10% nonfat milk, appropriate primary and secondary antibodies were applied, and the blots were developed with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Millipore, Temecula, CA, WBKLS0500). All the experiments were repeated at least three times.

2.5 Immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy

For immunofluorescence, cells cultured on 8-well chamber slides were fixed and stained as described previously [22]. All fluorescence images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 inverted fluorescence microscopy. For immunohistochemistry, mouse brains were fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Then paraffin-embedded brains were sliced into consecutive sections of 6 μm for the midbrain and striatum. The sections were sequentially incubated overnight at 4°C with appropriate primary antibodies. The sections were then incubated with either goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit (Millipore, Temecula, CA, AP124 or AP132) peroxidase conjugated antibody, followed by species-specific peroxidase anti-peroxidase complex (Jackson, West Grove, PA, 223005024 or 323005024). 3–3’-Diaminobenzidine (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, K3468) was used as a chromogen. For quantification of dopaminergic neurons, at least 4 sections of the SN region were immunostained for each mouse using tyrosine hydrolase antibody. The numbers of TH positive neurons were counted in a blinded manner using Axiovision software. Densitometric analysis of TH immunostained striatum area was performed using Axiovision software on mouse sections also blinded as to genotype and treatment. Electron microscopic analysis was performed as previously described [26]. Taken briefly, mouse brains were perfused with EM fixative (the quarter strength Karnovsky-1.25% DMSO mixture) and tissue blocks were postfixed in 1% osmium-1.25 % ferrocyanide mixture. Then specimens were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 embedding resin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Thin sections were sequentially stained with 2 % acidified uranyl acetate followed by Sato’s triple lead staining and examined in an FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope equipped with a Gatan single tilt holder and a CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). Mitochondrial were well separated in the raw EM images, making it possible to measure the mitochondrial length and width directly. At least 160 mitochondria and 4–5 neurons from each animal were measured.

2.6 Image analysis

ImageJ was used to quantify mitochondrial morphology in neurons as described previously [27, 28]. The fluorescent images were background corrected, linearly contrast optimized, applied with a 7 × 7 ‘top hat’ filter, subjected to a 3 × 3 median filter, and then thresholded to generate binary images. Most of the mitochondria were well separated in binary images and thus can be analyzed by Image J to provide the information of mitochondria aspect ratio. For primary neurons, mitochondria are well separated from each other and mitochondria length were measured directly from raw pictures. At least 100 SH-SY5Y cells/condition and 30 primary neurons/condition were analyzed in each experiment, and experiments were repeated at least three times.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The error bars on figures represent the mean ± SD of all determinations. For analysis of statistical difference between three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests were applied. p values are indicated by asterisks (**p < 0.01; *p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1 DLP1 is increased in SN from idiopathic PD patients

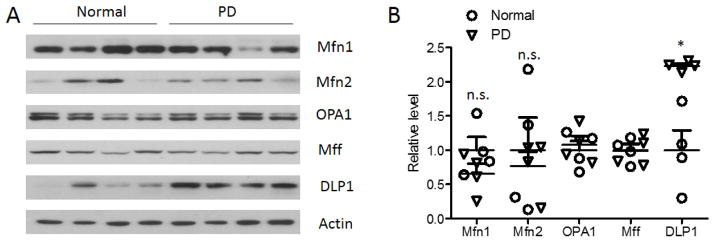

We investigated the expression of mitochondrial fission proteins (i.e., DLP1 and Mff) and fusion proteins (i.e., OPA1, Mfn1, and Mfn2) in SN tissues from idiopathic PD patients and age-matched normal subjects (Fig.1A, B) by western blot. The levels of Mfn1 and Mfn2 varied among different cases, and both appeared decreased in PD compared with age-matched control cases but did not reach significance. The expression of Mff and OPA1 was consistent among different cases but no significant changes were found in PD. However, the levels of DLP1 were consistently increased in all the PD cases examined and the quantitative analysis confirmed a significant increase in the levels of DLP1 in PD compared with controls, which suggest a likely impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in idiopathic PD cases.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial fusion and fission protein expression in the substantia nigra (SN) from PD and age-matched controls. Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification analysis (normalized to actin) (B) revealed significantly increased levels of DLP1 in the SN from PD patients. (*p<0.05, Student’s t test). Equal protein amounts (30 μg) of lysates were loaded and actin was blotted as an internal loading control. Each experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

3.2 PQ induces mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in neuronal cells

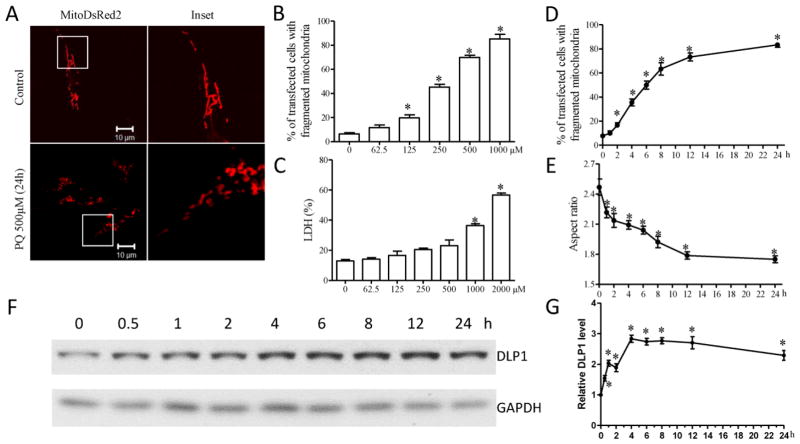

To study the roles of an altered mitochondrial dynamics in idiopathic PD, we used PQ, a PD-related environmental neurotoxin, to treat neuronal cells and rodents to model idiopathic PD. We first investigated the effect of PQ on mitochondrial dynamics in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with mitoDsRed2, a red fluorescent protein that specifically targets the mitochondrial matrix. Two days after transfection, cells were treated with a range of concentrations of PQ (0–2000 μM) for 24 h. Cells were fixed and mitochondrial morphology was visualized by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2A). In control SH-SY5Y cells, mitochondria demonstrated a tubular and filamentous morphology. However, PQ treatment at concentrations greater than 125 μM induced a significant dose-dependent increase in the percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria appearing as small and round structures (Fig. 2B). Significant cell death was only observed in cells treated by PQ at concentrations of 1000 μM and higher (Fig. 2C), suggesting that PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation is not an artifact due to increased cell death. We next performed a time-course study to determine the effect of PQ on mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 2D, E). Two days after transfection with mitoDsRed2, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 500 μM PQ and fixed at different time points between 0–24 h. PQ exposure led to significant mitochondrial fragmentation as evidenced by the appearance of small and round mitochondria in 17.0 ± 2.2% of cells at 2 h (Fig. 2D). The percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria increased to over 63 ± 4.2% by 8 h, reaching over 82 ± 1.2% by 24 h exposure to PQ. We also observed significantly decreased mitochondrial aspect ratio (ratio of length width as an index of mitochondria morphology) during the first hour of PQ incubation (Fig. 2E), which was further reduced at a relatively slower pace until 12 h post PQ treatment and plateaued thereafter. Consistently, western blot also revealed significantly increased DLP1 protein levels within 30 min of 500 μM PQ treatment which was further increased until 4 h post PQ treatment and plateaued thereafter (Fig. 2F, G).

Fig. 2.

PQ induces mitochondrial fragmentation in cultured SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. (A–C) SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with mitoDsRed2 to label mitochondria. Two days after transfection, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with different concentrations of PQ for an additional 24 h. Representative pictures (A) of mitoDsRed2-positively transfected cells treated with or without 500 μM PQ are shown. (B) Quantification of mitochondrial morphology revealed PQ induced mitochondrial fragmentation in a dose-dependent manner. (C) The LDH release assay was performed to evaluate cell death induced by 24 h treatment of different concentrations of PQ. (D,E) Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in SH-SY5Y cells treated with 500 μM PQ at different time points. The aspect ratio of a mitochondrion is a ratio between the major and the minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondria. (F,G) Time course study of the changes in the expression of DLP1 in SHSY5Y cells by the treatment of 500 μM PQ. At least 100 cells/condition were analyzed in each experiment, and experiments were repeated three times. (*p<0.05, when compared with control cells without PQ treatment.)

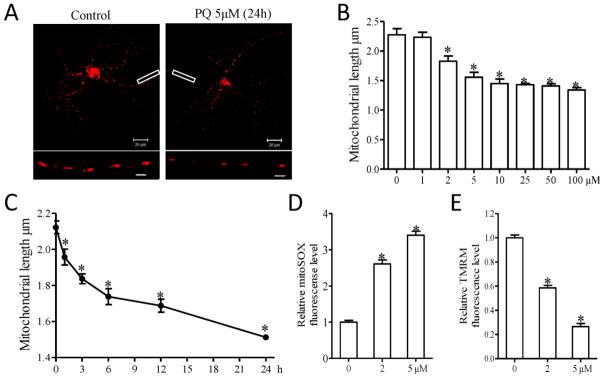

The effects of PQ on mitochondrial dynamics were also investigated in primary neurons. In fact, much lower concentration of PQ was needed to exert similar effects on mitochondrial fragmentation in primary rat E18 neuronal cultures (Fig. 3A): PQ treatment starting at concentrations as low as 2 μM caused a significant dose-dependent increase in mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 3B). In the time course study, 5 μM PQ treatment led to a rapid decrease of mitochondrial length in primary cortical neurons within the first 3 h which continued at a relatively slower pace until 24 h of PQ treatment (Fig. 3C). Importantly, changes in mitochondrial function were also observed at these conditions: by using MitoSOX, a fluorescence red dye to measure mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, we found a more than 2.5 fold significant increase in mitochondrial ROS levels in neurons treated with 2 μM PQ which was further increased by treatment with 5 μM PQ (Fig. 3D). There was a similar PQ-induced dose-dependent decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), another important marker of mitochondrial function, measured by using the fluorescence dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

PQ induces mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in primary rat cortical neurons. (A–C) Primary rat cortical neurons (DIV4) were transfected with mitoDsRed2 to label mitochondria. Two days after transfection, neurons (DIV6) were treated with different concentrations of PQ for an additional 24 h (B) or 5 μM PQ with different duration (C). Representative pictures (A) of mitoDsRed2-positively transfected neurons with or without 5 μM PQ for 24 h are shown. Insert scale bar, 3 μm. (B,C) Quantification of mitochondrial length in positively transfected neurons. (D,E) Primary cortical neurons (DIV6) were treated with indicated concentrations of PQ for 24 h, then mitochondrial superoxide production (D) and mitochondrial membrane potential (E) were measured. At least 30 primary neurons/condition were analyzed in each experiment, and experiments were repeated three times. (*p<0.05, when compared with control neurons without PQ treatment.)

3.3 PQ induces increased DLP1 and mitochondrial fragmentation in vivo

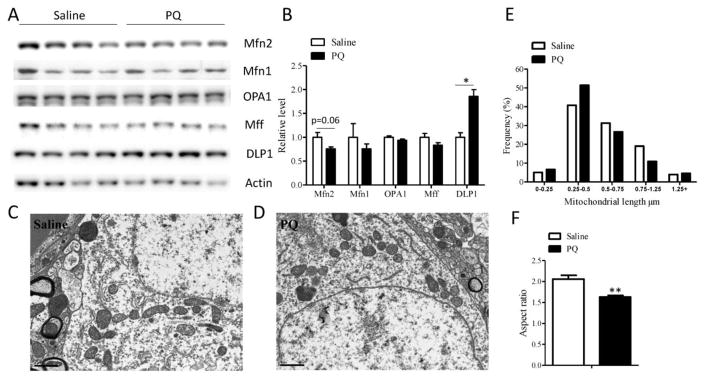

To study the PQ effect on mitochondrial dynamics in vivo, mice were treated with PQ (i.p. 10 mg/kg) or saline twice a week for four weeks and sacrificed one week after the last injection. SN tissues from these mice were used to study the expression of mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins by western blot (Fig. 4A, B). Similar to that of idiopathic PD, there was a trend toward reduced expression of Mfn1 and Mfn2 in the SN tissues in PQ-treated mice, in fact, the reduction of Mfn2 almost reach significance (p=0.06). No significant changes in the expression of OPA1 and Mff were found in PQ-treated mice. However, the levels of DLP1 were significantly increased in the SN from PQ-treated mice compared with controls, which is similar to the observation of elevated DLP1 levels in the idiopathic PD cases, suggesting a tipped balance of mitochondrial fission/fusion caused by PQ treatment in vivo.

Fig. 4.

PQ induces increased DLP1 expression and mitochondrial fragmentation in the substantia nigra in vivo. Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification analysis (normalized to actin) (B) revealed significantly elevated levels of DLP1 in SN from PQ-based PD mouse model. N=6 in each group for quantification in (B) although a representative immunoblot of four per group was shown in (A). Equal protein amounts (30 μg) of lysates were loaded and actin was used as an internal loading control. (C-F) Representative electron micrographs of midbrain neurons from SN of 12-week old WT mice treated by saline (C) or PQ (D). The mice received I.P. injections of 10 mg/kg PQ or equal amount of saline twice in a week. 3 days after last injection, brains were prepared for EM study. Quantification of frequency (E) and aspect ratio (F) of mitochondria in midbrain neurons of SN. Scale bar, 1 μm. At least 160 mitochondria and 4–5 neurons per animal were measured. (**p<0.01, when compared with control.)

To directly visualize PQ-induced mitochondrial morphological changes in the substantia nigra in vivo, ultrastructural study was performed by electron microscopy. Small round mitochondria were more frequently observed in the midbrain neurons of mice after PQ treatment compared with neurons from the saline-treated control mice (Fig. 4C, D). Analysis of the distribution of mitochondrial length demonstrated a higher percentage of short mitochondria less than 0.5 μm in PQ-treated mice (Fig. 4E). The average length of mitochondria in the neurons of saline treated mice was 0.60 ± 0.03 μm, which was significantly decreased to 0.54 ± 0.03 μm (p<0.05) in the neurons of PQ-treated mice. In PQ-treated mice, the mitochondrial aspect ratio (length/width of individual mitochondria) was also significantly decreased compared to the control mice (Fig. 4F), suggestive of mitochondrial fragmentation in vivo.

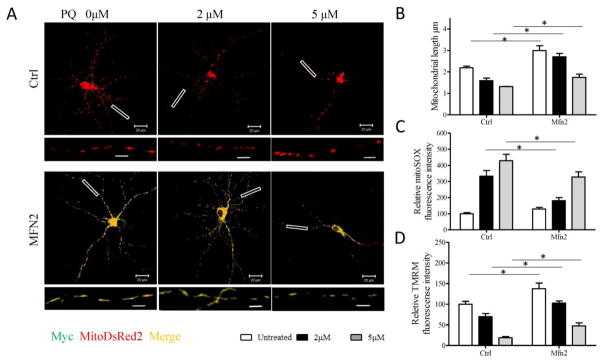

3.4 Inhibition of PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction in neuronal cells

To investigate the causal relationship between PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction, we determined whether overexpression of Mfn2, a critical mitochondrial fusion factor, protects primary cortical neurons from PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction. Primary cortical neurons were cotransfected with mitoDsRed2 and either myc-tagged-Mfn2 or myc-empty vector. 48 h after transfection, neuronal cells were treated with 2 and 5 μM PQ for an additional 24 h and fixed for confocal microscopy analysis of mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 5A). As expected, Mfn2 overexpression effectively inhibited mitochondrial fragmentation induced by PQ treatment in primary cortical neurons (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Mfn2 overexpression rescues PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction in primary rat cortical neurons. Primary rat cortical neurons (DIV4) were co-transfected with Myc-tagged Mfn2 and mitoDsRed2 (A,B) or GFP (C,D) at a 9:1 ratio to enable that most of mitoDsRed2 or GFP transfected neurons to be also Myc-positive. Two days after transfection, neurons were treated with 0, 2, or 5 μM PQ for 24 h. Representative pictures (A) of mitoDsRed2- (red) and Mfn2- (stained by Myc antibody shown in green) positively transfected neurons and quantification (B) of mitochondrial length in these neurons were shown. In another experiment, GFP positively transfected neurons were used to measure mitochondrial superoxide production (C) and mitochondrial membrane potential (D). Insert scale bar, 4 μm. (*p<0.05, when compared with control.) At least 30 primary neurons/condition were analyzed in each experiment, and experiments were repeated three times.

Next, primary neurons were cotransfected with GFP and either myc-tagged-Mfn2 or myc-empty vector for measuring mitochondrial superoxide production and mitochondrial membrane potential. Importantly, Mfn2 overexpression also alleviated PQ-induced increase of mitochondrial ROS as well as PQ-induced decrease of MMP (Fig. 5C, D).

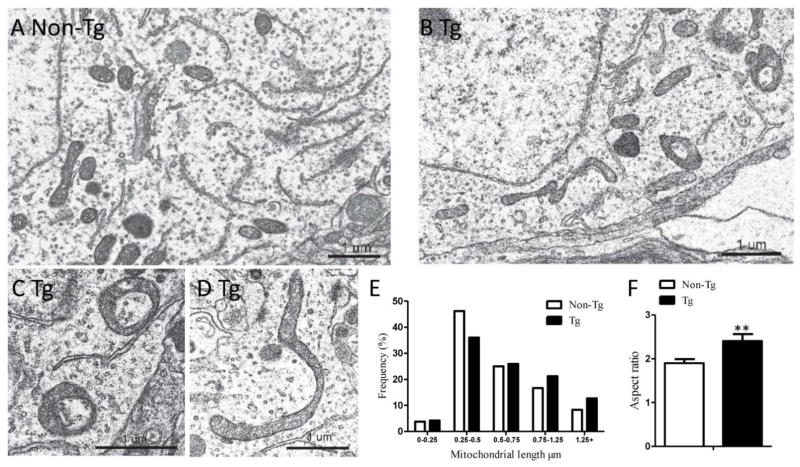

3.5 hMfn2 Tg mice demonstrated elongated mitochondria in the substantia nigra

To investigate whether inhibition of mitochondrial fragmentation protects DA neurons from PQ toxicity in vivo, we made use of a transgenic mouse model overexpressing human Mfn2 under the Thy1.2 promoter (hMfn2 Tg mouse) [26]. As expected, electron microscopy demonstrated that elongated mitochondria were more frequently observed in the midbrain neurons of the hMfn2 Tg mice compared with neurons from the non-Tg littermate control mice (Fig. 6A. B). Analysis of the distribution of mitochondrial length demonstrated a higher percentage of long mitochondria exceeding 0.75 μm in hMfn2 Tg mice (Fig. 6E). The average length of mitochondria in the non-Tg littermate control mice was 0.63 ± 0.02 μm and they exhibited a normal size distribution with many small, round mitochondria as well as longer, cylindrical shaped mitochondria (Fig. 6A, E). The average length of mitochondria in the hMfn2 Tg neurons was significantly increased to 0.76 ± 0.04 μm (p<0.01), with most mitochondria exhibiting the longer, sausage shape (Fig. 6B, E). Very elongated mitochondria were also seen, and many were curved with their ends connected appearing as a circular donut shapes (Fig. 6C, D). In the hMfn2 Tg mice, the mitochondria aspect ratio (length/width of individual mitochondria) was significantly larger compared to the control mice (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

EM analysis of mitochondrial morphology demonstrated mitochondrial elongation in the midbrain neurons of Mfn2 Tg mice. (A–D) Representative electron micrographs of midbrain neuron from SN of 16-week old non-Tg (A) and Mfn2 Tg mouse (B–D). Quantification of frequency (E) and aspect ratio (F) of mitochondria in midbrain neurons of SN. Scale bar, 1 μm. At least 200 mitochondria of more than 4 neurons per animal were measured. (**p<0.01, when compared with control.)

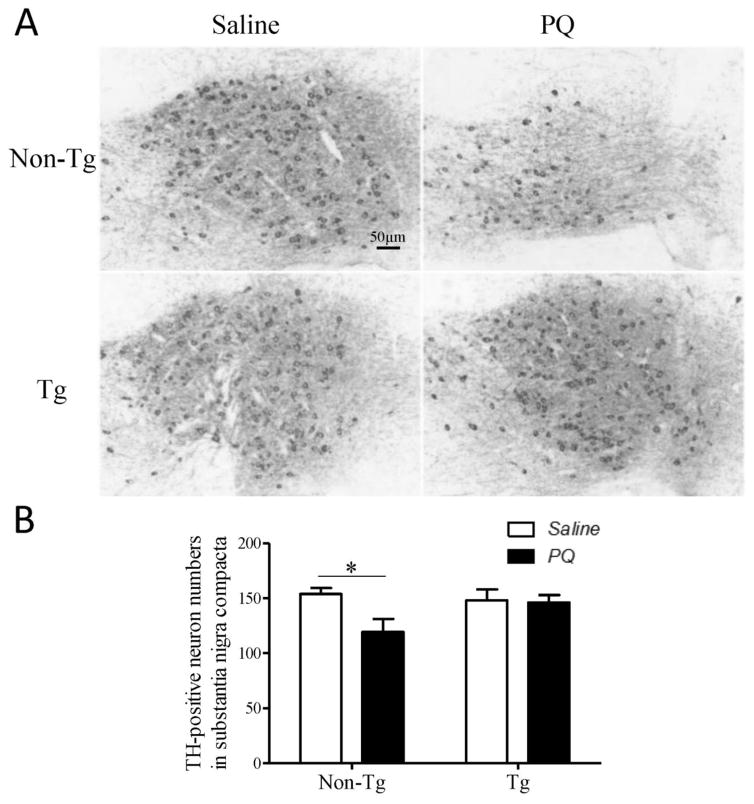

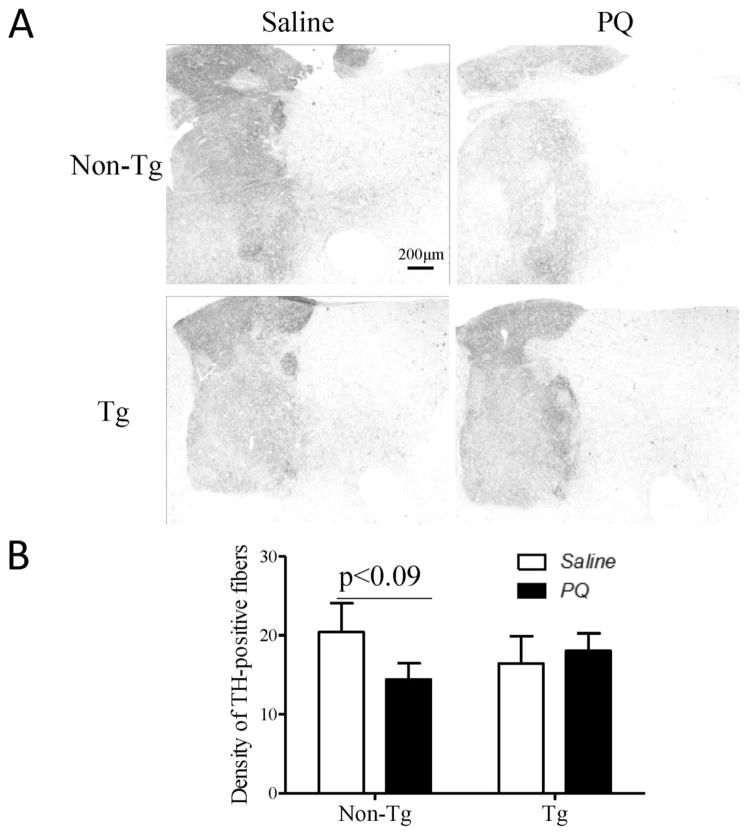

3.6 Mfn2 overexpression protects DA neurons against PQ toxicity in vivo

hMfn2 Tg and their Non-Tg littermate control mice were treated with PQ (i.p. 10 mg/kg) or saline twice a week for four weeks and sacrificed one week after the last injection. In mice treated with saline, no significant difference in the number of DA neurons in the SN was noted between hMfn2 Tg mice and their non-Tg littermate controls and the density of TH-positive axonal termini in the striatum was comparable between the two genotypes. The number of TH-positive neurons was significantly reduced by around 20% in the PQ-treated non-Tg mice as compared with that in the saline-treated non-Tg mice (Fig. 7A). By contrast, no reduction in the number of TH-positive neurons was noted in the hMfn2-Tg mice as compared with that in the saline-treated hMfn2 Tg mice (Fig. 7B). Similarly, while the density of striatal TH-positive axon termini was reduced by around 30% in PQ treated non-Tg mice as compared with that in the saline treated non-Tg mice, a comparable density of TH-positive axon termini was present in PQ- and saline-treated hMfn2 Tg mice (Fig. 8A, B).

Fig. 7.

Mfn2 protects dopaminergic neurons in SN against PQ toxicity in vivo. Mfn2 Tg mice and non-Tg mice were treated with PQ (10 mg/kg) or vehicle control saline twice a week for 4 weeks. 7 days after last injection, the half brains were fixed for TH immunostaining. Representative pictures (A) and quantification of dopaminergic neurons (B) in the SNpc were shown. (N=8/group, *p<0.05, when compared with control.)

Fig. 8.

Mfn2 rescues dopaminergic terminals in the striatum against PQ toxicity in vivo. Representative pictures of dopaminergic terminals (A) in the striatum and quantification of the TH staining intensity (B) in this area (N=4/group).

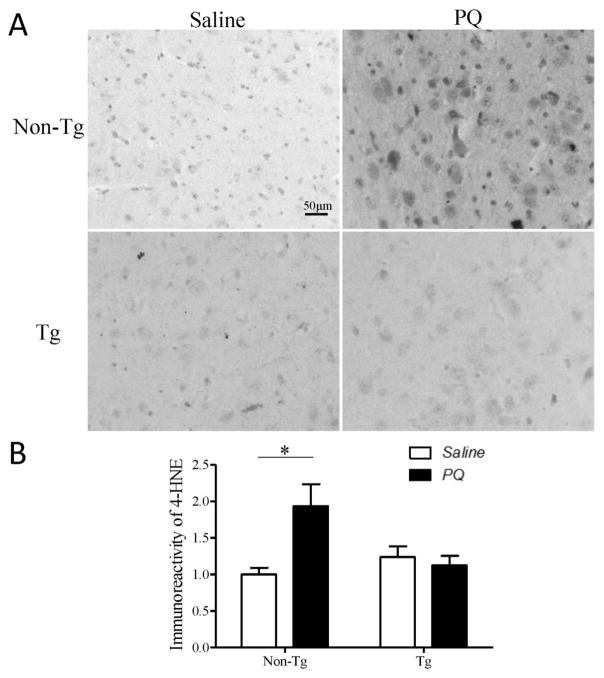

3.7 Mfn2 overexpression blocks PQ-induced oxidative stress signaling in vivo

Oxidative stress is believed to play a major role in mediating PQ-induced toxicity. We analyzed levels of 4-HNE, an α, β-unsaturated aldehyde produced during oxidation of membrane lipid polyunsaturated fatty acids, as a measure of oxidative damage in PQ-treated mice. PQ treatment led to a significant increase in 4-HNE immunoreactivity in SN of non-Tg control mice (Fig. 9A, B) which was almost completely blocked in hMfn2 Tg mice (Fig. 9A, B).

Fig. 9.

Mfn2 alleviates PQ-induced oxidative stress in the SN in vivo. Fixed brains of PQ- or saline-treated Mfn2 Tg and non-Tg mice were immunostained for 4-HNE. Representative pictures (A) and quantification (B) of 4-HNE immunoreactivity in SN (N=4/group). Scale bar, 50 μm. (*p<0.05, when compared with control.)

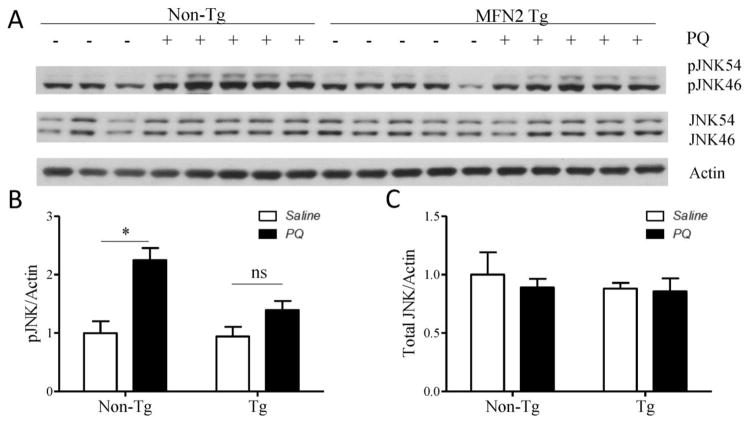

As a stress activated kinase, JNK activation is involved in PQ-induced DA neuronal death [29]. There was no difference in the levels of JNK phosphorylation between hMfn2 Tg mice and non-Tg littermate controls at basal levels (Fig. 10A). However, JNK phosphorylation was significantly increased in non-Tg mice treated with PQ compared to saline-treated non-Tg mice (Fig. 10A, B), but no increase in JNK phosphorylation was observed in PQ-treated hMfn2 Tg mice compared to saline-treated hMfn2 Tg mice.

Fig. 10.

Mfn2 alleviates PQ-induced pJNK activation in vivo. WT and Mfn2 mice were treated with PQ or saline. From each half brain, the striatum was dissected for immunoblotting analysis. Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification of pJNK (B) and JNK (C) protein levels in striatum. (*p<0.05, when compared with control.)

4. Discussion

In the current study, we focused on the balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in idiopathic PD and PQ-treated neuronal cells and mice as in vitro and in vivo models of idiopathic PD and reported several novel findings: 1) there is significant increase in the expression of mitochondrial fission protein DLP1 in the SN tissues from idiopathic PD patients compared with age-matched normal controls; 2) As an in vitro model of PD, PQ treatment led to increased DLP1 expression along with increased mitochondrial fragmentation and mitochondrial dysfunction in SH-SY5Y cells and primary cortical neurons; 3) Blocking PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation in vitro by overexpressing Mfn2 could alleviate PQ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction such as increased ROS production and decreased MMP; 4) PQ treatment led to increased DLP1 expression and decreased Mfn2 expression and increased mitochondrial fragmentation in the SN tissues in vivo along with loss of DA neurons; 5) PQ-induced DA degeneration and oxidative stress signaling was inhibited in the transgenic mice overexpressing hMfn2 in vivo.

Prior studies based on genetic factors associated with familial PD suggest that disturbed mitochondrial dynamics is likely involved in the pathogenesis of PD. More specifically, studies on mouse models of PD with manipulated expression of PD-related proteins, either transgenic or virus-based, revealed mitochondrial fragmentation in DA neurons in vivo caused by PD-associated pathogenic mutations. However, detailed studies on changes in mitochondrial fission/fusion in idiopathic PD is scarce. One recent study demonstrated reduced mitochondrial DLP1 levels in the astrocytes from the PD brains which likely impaired the ability of astrocytes to adequately protect neurons from glutamate excitotoxicity, but the total levels of DLP1 and expression of other fission/fusion proteins were not determined [30]. In this study, we found significantly increased levels of mitochondrial fission protein DLP1 and a trend toward reduced expression of mitochondrial fusion proteins Mfn1 and Mfn2 in SN from idiopathic PD patients compared with age-matched normal controls. Given that mitochondrial dynamic is regulated by the delicate balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins, these results suggest, like those familial PD, an enhanced mitochondrial fission likely also occurs in SN of idiopathic PD. However, the lack of biopsied tissues from idiopathic PD patients prevents us from obtaining more definite and direct ultra-morphometric evidence of mitochondrial morphology in DA neurons of PD. Since environmental factors likely play a larger role in the pathogenesis of idiopathic PD, studies on the role of mitochondrial dynamics in PD-associated neurotoxin models may provide valuable information. Among various pesticides/herbicides present in the environment, it is demonstrated that only pesticides/herbicides that cause either mitochondrial dysfunction or oxidative stress are unequivocally associated with PD or clinical features of parkinsonism in humans [4]. We previously demonstrated that MPP+, a selective and potent mitochondrial complex I inhibitor as a representative of those that exert toxicity through mitochondrial dysfunction, caused increased DLP1 expression and DLP1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation that works downstream or in parallel with MPP+-induced bioenergetics dysfunction to mediate its toxicity in neuronal cells. In this study, we focused on PQ, an efficient redox-cycling compound as a representative of those that exert toxic effects largely through increased oxidative stress: PQ exposure caused a rapid and significant increase in the DLP1 levels in SH-SY5Y cells within 30 min which was accompanied by a rapid and significant decrease in mitochondrial aspect ratio, suggestive of mitochondrial fragmentation likely due to enhanced fission, within the first hour of treatment. More importantly, PQ treatment in mice also led to increased DLP1 expression and a trend towards reduced Mfn1/2 expression in the SN tissues that closely resembles the biochemical changes observed in the SN tissues from idiopathic PD, which was also accompanied by extensive mitochondrial fragmentation as demonstrated by the electron microscopy and confirmed by significantly decreased mitochondrial aspect ratio in DA neurons in SN tissues of PQ-treated mice. Collectively, these data demonstrate that environmental factors such as PD-associated neurotoxins (i.e., MPTP and PQ) tip the balance of mitochondrial dynamics towards enhanced fission with the outcome of mitochondrial fragmentation both in vitro and in vivo which could contributes to the biochemical changes observed in the SN tissues of idiopathic PD and potentially elicit a similar mitochondrial fragmentation phenotype in the SN tissues of idiopathic PD.

In this study, we demonstrated that PQ caused significant mitochondrial fragmentation in neuronal cells both in vitro and in vivo along with changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins (i.e., increased DLP1 and reduced Mfn1/2 in vivo). Mitochondrial fragmentation induced by PQ occurs without apparent cell death in SH-SY5Y cells and primary cortical neurons which suggests that PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation is unlikely an artifact due to PQ-induced cell death. As an efficient redox cycling compound, PQ exerts its toxicity through enhanced ROS production. Indeed, we also found increased mitochondrial ROS production in PQ-treated cells. It is not uncommon that exposure to exogenous stresses including oxidative stress shifts the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion dramatically toward fission although the underlying specific mechanisms may vary. For example, H2O2 led to mitochondrial fragmentation and osteoblast dysfunction in a osteoblast injury model by increasing levels of phosphorylation and expression of DLP1 [31]; while in yeast and mouse embryonic fibroblasts, H2O2-induced mitochondrial fragmentation involves cytoplasmic translocation of cyclin c which enhances mitochondrial recruitment of DLP1 through direct interaction [32]. A variety of cellular stress could activate stress activated kinase JNK which in turn phosphorylates Mfn2 and triggers its ubiquitination and degradation through the ubiquitin proteasomal pathway [33]. Therefore, increased DLP1 levels and reduced Mfn1/2 levels likely mediated PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation although and mitochondrial fragmentation through enhanced ROS production although detailed mechanisms remain to be worked out.

To explore the causal role of mitochondrial dynamics in PQ-treated cells and animals as a way to explore its potential role in idiopathic PD, we chose to overexpress Mfn2 in PQ-treated models because 1) Mfn2 plays an essential role in maintaining the balance of mitochondrial dynamics in dopaminergic neurons since its depletion causes dopaminergic neuronal loss [34, 35]; 2) DLP1 knockdown may have unwanted negative effects on mitochondrial transport that may complicate the interpretation of results [36, 37]. Indeed, overexpression of Mfn2 blocks PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, and significantly inhibits PQ-induced mitochondrial superoxide production in primary cortical neurons in vitro. Moreover, PQ administration caused significantly increased oxidative damage and activated stress signaling in nigral neurons in vivo as indicated by elevated immunoreactivity of 4-HNE, and increased JNK phosphorylation, a likely response to increased ROS that mediates neurodegeneration signaling [38, 39], both of which are inhibited in the transgenic mice overexpressing hMfn2 in the brain. Given that excessive mitochondrial fission elicits increased ROS production [27, 40], these studies suggest that PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation amplifies PQ-induced oxidative stress. This is also consistent with the prior finding that mitochondria are a major source of ROS production induced by PQ in the brain [41]. More importantly, the blockage of PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation by Mfn2 overexpression rescues mitochondrial membrane potential decline in primary cortical neurons in vitro and significantly alleviates PQ-induced loss of DA neurons in SN and TH-positive axonal terminals in the striatum in vivo, which suggest that PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation plays a critical role in mediating its toxic effects on mitochondrial function and DA neuronal death. Our studies further demonstrated that restoring mitochondrial dynamics may be a valid intervention target to prevent mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction induced by environmental toxins.

Overall, our study demonstrates changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins in the substantia nigra of idiopathic PD, suggesting that impaired mitochondrial dynamics is likely involved in the course of idiopathic PD. We further demonstrated that PQ induces similarly changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins along with mitochondrial fragmentation both in vitro and in vivo which plays a critical role in amplifying ROS production and mediating mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death, suggesting that PD-associated environmental neurotoxins could contribute to changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion protein in idiopathic PD and cause mitochondrial dysfunction and DA neuronal death by disturbing mitochondrial dynamics. Therefore, also considering abundant evidence of the involvement of abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in models of familial PD, excessive mitochondrial fission could serve as a promising therapeutic target for both familial and sporadic PD.

Highlights.

Expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins was changed in the PD brain

PQ caused similar changes in the expression of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins

PQ caused mitochondrial fragmentation in vitro and in vivo

Mfn2 prevents PQ-induced mitochondrial fragmentation/dysfunction and neuronal loss

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Fangqiang Tang for helping with the characterization of the Mfn2 Tg mice

This work is partly supported by National Institute of Health [grant numbers NS083385 and NS083498 (to X. Zhu)] and by the Dr. Robert M. Kohrman Memorial Fund. Some tissues were provided by the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, which is supported in part by PHS contract, HHS-NIH-NIDA (MH)-13-265.

Abbreviations

- DA

dopaminergic

- DIV

days in vitro

- DLP1

dynamin-like protein 1

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- JNKs

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MAP2

microtubule-associated protein-2

- Fis1

mitochondrial fission 1

- Mff

mitochondrial fission factor

- Mfn2

mitofusin 2

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- Mfn1/2

mitofusin 1/2

- OPA1

optic atrophy 1

- PQ

paraquat

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SN

substantia nigra pars compacta

- TMRM

tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- Tg

transgenic

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jankovic J. Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenamyre JT, Betarbet R, Sherer TB. The rotenone model of Parkinson's disease: genes, environment and mitochondria. Parkinsonism relat Disord. 2003;9(Suppl 2):S59–64. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(03)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Maele-Fabry G, Hoet P, Vilain F, Lison D. Occupational exposure to pesticides and Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ Int. 2012;46:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priyadarshi A, Khuder SA, Schaub EA, Shrivastava S. A meta-analysis of Parkinson's disease and exposure to pesticides. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21:435–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pezzoli G, Cereda E. Exposure to pesticides or solvents and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80:2035–2041. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b3c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freire C, Koifman S. Pesticide exposure and Parkinson's disease: epidemiological evidence of association. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:947–971. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry C, La Vecchia C, Nicotera P. Paraquat and Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1115–1125. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappold PM, Cui M, Chesser AS, Tibbett J, Grima JC, Duan L, Sen N, Javitch JA, Tieu K. Paraquat neurotoxicity is mediated by the dopamine transporter and organic cation transporter-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20766–20771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115141108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks AI, Chadwick CA, Gelbard HA, Cory-Slechta DA, Federoff HJ. Paraquat elicited neurobehavioral syndrome caused by dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain Res. 1999;823:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormack AL, Thiruchelvam M, Manning-Bog AB, Thiffault C, Langston JW, Cory-Slechta DA, Di Monte DA. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson's disease: selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:119–127. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL, van der Bliek AM. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2245–2256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loson OC, Song Z, Chen H, Chan DC. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:659–667. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cipolat S, Martins de Brito O, Dal Zilio B, Scorrano L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15927–15932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407043101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics--fusion, fission, movement, and mitophagy--in neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R169–176. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang C, Cao JH, Huh JR, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Hay BA, Guo M. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Dorn GW., 2nd PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gui YX, Wang XY, Kang WY, Zhang YJ, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Quinn TJ, Liu J, Chen SD. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase is involved in alpha-synuclein-induced mitochondrial dynamic disorders by regulating dynamin-like protein 1. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2841–2854. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamp F, Exner N, Lutz AK, Wender N, Hegermann J, Brunner B, Nuscher B, Bartels T, Giese A, Beyer K, Eimer S, Winklhofer KF, Haass C. Inhibition of mitochondrial fusion by alpha-synuclein is rescued by PINK1, Parkin and DJ-1. EMBO J. 2010;29:3571–3589. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Yan MH, Fujioka H, Liu J, Wilson-Delfosse A, Chen SG, Perry G, Casadesus G, Zhu X. LRRK2 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and function through direct interaction with DLP1. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1931–1944. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Petrie TG, Liu Y, Liu J, Fujioka H, Zhu X. Parkinson's disease-associated DJ-1 mutations impair mitochondrial dynamics and cause mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurochem. 2012;121:830–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Wang X, Fujioka H, Hoppel C, Whone AL, Caldwell MA, Cullen PJ, Liu J, Zhu X. Parkinson's disease-associated mutant VPS35 causes mitochondrial dysfunction by recycling DLP1 complexes. Nat Med. 2016;22:54–63. doi: 10.1038/nm.3983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidal M, Morris R, Grosveld F, Spanopoulou E. Tissue-specific control elements of the Thy-1 gene. EMBO J. 1990;9:833–840. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Zhang F, Li L, Tang F, Siedlak SL, Fujioka H, Liu Y, Su B, Pi Y, Wang X. MFN2 couples glutamate excitotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction in motor neurons. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:168–182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.617167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Su B, Liu W, He X, Gao Y, Castellani RJ, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. DLP1-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation mediates 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in neurons: implications for Parkinson's disease. Aging Cell. 2011;10:807–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Vos KJ, Sheetz MP. Visualization and quantification of mitochondrial dynamics in living animal cells. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;80:627–682. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng J, Mao XO, Stevenson FF, Hsu M, Andersen JK. The herbicide paraquat induces dopaminergic nigral apoptosis through sustained activation of the JNK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32626–32632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoekstra JG, Cook TJ, Stewart T, Mattison H, Dreisbach MT, Hoffer ZS, Zhang J. Astrocytic dynamin-like protein 1 regulates neuronal protection against excitotoxicity in Parkinson disease. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:536–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan X, Huang S, Yu Q, Yu H, Yan SS. Blockade of Drp1 rescues oxidative stress-induced osteoblast dysfunction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;468:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang K, Yan R, Cooper KF, Strich R. Cyclin C mediates stress-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:1030–1043. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-08-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leboucher GP, Tsai YC, Yang M, Shaw KC, Zhou M, Veenstra TD, Glickman MH, Weissman AM. Stress-induced phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of mitofusin 2 facilitates mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2012;47:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, Sterky FH, Mourier A, Terzioglu M, Cullheim S, Olson L, Larsson NG. Mitofusin 2 is necessary for striatal axonal projections of midbrain dopamine neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4827–4835. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pham AH, Meng S, Chu QN, Chan DC. Loss of Mfn2 results in progressive, retrograde degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal circuit. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4817–4826. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Su B, Siedlak SL, Moreira PI, Fujioka H, Wang Y, Casadesus G, Zhu X. Amyloid-beta overproduction causes abnormal mitochondrial dynamics via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission/fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19318–19323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804871105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi WS, Abel G, Klintworth H, Flavell RA, Xia Z. JNK3 mediates paraquat- and rotenone-induced dopaminergic neuron death. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:511–520. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181db8100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunot S, Vila M, Teismann P, Davis RJ, Hirsch EC, Przedborski S, Rakic P, Flavell RA. JNK-mediated induction of cyclooxygenase 2 is required for neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:665–670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu T, Sheu SS, Robotham JL, Yoon Y. Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:341–351. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castello PR, Drechsel DA, Patel M. Mitochondria are a major source of paraquat-induced reactive oxygen species production in the brain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14186–14193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700827200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]