Abstract

Background & Aims

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in patients with cirrhosis that increases mortality. The most common causes of AKI in these patients are prerenal azotemia, acute tubular necrosis (ATN), and hepatorenal syndrome; it is important to determine the etiology of AKI to select the proper treatment and predict patient outcome. Urine biomarkers could be used to differentiate between patients with ATN and functional causes of AKI. We performed a systemic review and meta-analysis of published studies to determine whether urine levels of interleukin 18 (IL18) and lipocalin 2 (LCN2 or NGAL) associate with development of ATN in patients with cirrhosis.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Scopus, ISI Web of Knowledge, and conference abstracts, through December 31, 2015, for studies that assessed urine biomarkers for detection of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis or reported an association between urine biomarkers and all-cause mortality in these patients. We included only biomarkers assessed in 3 or more independent studies, searching for terms that included urine biomarkers, liver cirrhosis, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, NGAL, interleukin 18, and IL18. We calculated pooled sensitivities and specificities for detection and calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values using a bivariate logistic mixed-effects model. We used the χ2 test to assess heterogeneity among studies.

Results

We analyzed data from 8 prospective studies, comprising 1129 patients with cirrhosis. We found urine levels of the markers discriminated between patients with ATN and other types of kidney impairments, with AUC values of 0.88 for IL18 (95% CI, 0.79–0.97) and 0.89 for NGAL (95% CI, 0.84–0.94). Urine levels of IL18 identified patients who would die in-hospital or within 90 days (short-term mortality) with an AUC value of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.68–0.85); NGAL identified these patients with the same AUC (0.76; 95% CI, 0.71–0.82).

Conclusions

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that urine levels of IL18 and NGAL from patients with cirrhosis discriminate between those with ATN and other types of kidney impairments, with AUC values of 0.88 and 0.89, respectively. Urine levels of IL18 and NGAL identified patients with short-term mortality with an AUC value of 0.76. These biomarkers might be used to determine prognosis and select treatments for patients with cirrhosis.

Keywords: prognostic factor, prediction, survival, cytokine

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in patients with cirrhosis and is associated with significant mortality.1–3 The most common causes of AKI in this setting are prerenal azotemia (PRA), acute tubular necrosis (ATN), and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and accurately determining the etiology of AKI is paramount as treatments differ considerably.1–6 Moreover, prognosis of patients with cirrhosis differs markedly according to the etiology of AKI.1, 4, 7, 8 Current methods for distinguishing the cause of AKI involve urine microscopy and FENa. Because these methods are often inaccurate and can potentially lead to the administration of harmful treatments and misallocation of resources, novel diagnostic methods have been sought. Urine biomarkers have been developed as potential alternatives to standard tests for the differentiation of structural (ATN) and functional (HRS and PRA) causes of AKI.9, 10 Additionally, the most intensive therapies should ideally be reserved for those at greatest risk of short-term mortality. However, due to the lack of good prognostic tools in this setting, patients often receive multiple therapies irrespective of whether they are at risk for adverse outcomes. Therefore, urine biomarkers capable of predicting short-term mortality in patients with cirrhosis and AKI may allow for more rapid and targeted treatment.6, 11

Among the most promising urine biomarkers are interleukin 18 (IL18) and lipocalin 2 (LCN2 or NGAL). IL18 and NGAL are expressed in renal tubular cells and eliminated into the urine in response to tubular injury and have been shown to be strong predictors of mortality in multiple settings.9, 10, 12–14 Recently, several studies have examined the diagnostic and prognostic ability of IL18 and NGAL in patients with cirrhosis with AKI.15–25 To our knowledge, no study has comprehensively summarized the evidence surrounding the efficacy of these markers in this setting. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to assess the ability of urine IL18 and NGAL to differentiate ATN versus functional kidney disease and to assess the ability of these biomarkers to predict all-cause mortality.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

The systematic review and meta-analysis was prepared in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. We systematically searched MEDLINE, Scopus, and ISI Web of Knowledge without date or language restrictions. The last search was conducted on December 31, 2015. We also searched conference abstracts from the American Society of Nephrology, European Renal Association – European Dialysis and Transplant Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and European Association for the Study of the Liver from January 2010 to December 2015. In addition, bibliographies of review articles and all included studies were hand-searched to identify other relevant studies. We included studies if they assessed the accuracy of one or more urine biomarkers in detecting ATN in patients with cirrhosis. In addition, we included studies that reported the association of one or more urine biomarkers with all-cause mortality in patients with cirrhosis. We only included biomarkers assessed in three or more independent studies. Keywords used for the search were “urine biomarkers and liver cirrhosis”, “NGAL and liver cirrhosis”, “urine NGAL and liver cirrhosis”, “Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and liver cirrhosis”, “Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin”, “urine NGAL”, “urine IL18 and liver cirrhosis”, “interleukin 18 and liver cirrhosis”, and “urine IL18”.

Data Extraction and Assessment of Quality

Two investigators independently (X.A. and J.P.) extracted the data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or if necessary, they were resolved by referral to a third investigator. For each study, the following information was extracted: the first author’s last name, year of publication, country, study design, biomarkers assessed, patient setting, hospital type, sample size, age, gender, severity of liver disease, and details of the assays and cutoffs used. For studies using biomarkers to discriminate ATN from other types of kidney impairment, the definitions of kidney impairment and ATN used, number of patients with kidney impairment, and number of patients with ATN were extracted. For studies using biomarkers to predict all-cause mortality, the duration of follow-up, number of patients followed, and number of patients who died during the follow-up period were extracted. Each investigator also recorded the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) for each biomarker for each outcome. We contacted the corresponding authors if further information was needed. Six authors were contacted and five provided the requested information. We assessed the methodological quality of studies using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) tool (Supporting Table 1).26

Statistical Analysis

We performed meta-analyses for sensitivity and specificity using a bivariate logistic mixed-effects model. We calculated the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives for each study, and from these, we estimated the pooled sensitivity and specificity with its 95% confidence interval. We assumed random effects with a bivariate normal distribution.

In addition, we performed meta-analyses for the AUC for each outcome. If the study reported the AUC and 95% confidence interval instead of the standard error, we imputed the standard error by dividing the difference between the upper and lower confidence interval by 3.92.27 We pooled the individual study estimates under the random-effects model and expressed the overall estimate as a pooled AUC with its 95% confidence interval. When evaluating the pooled study estimates, we considered poor accuracy as less than 0.7, moderate accuracy as 0.7 to 0.8, excellent as 0.8 to 0.9, and outstanding accuracy as greater than 0.9.28 We calculated I2 to assess heterogeneity across studies. When evaluating heterogeneity, we considered no heterogeneity as less than 25%, low heterogeneity as 25% to 50%, moderate heterogeneity as 50% to 75%, and high heterogeneity as greater than 75%.29 Publication bias was assessed visually by inspecting funnel plots and statistically by using Egger’s regression model.30

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and MedCalc version 12.3 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

RESULTS

Study Identification and Selection

The study selection process is shown in Figure 1. Our database search identified 264 citations, from which 54 were selected for full-text evaluation. From these, we identified eight articles eligible to be included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Study Characteristics and Data Collection

The characteristics of the eight studies included in the meta-analysis are reported in Table 1. These prospective studies encompassed 1129 patients with cirrhosis enrolled from university-affiliated tertiary care centers. The sample sizes of individual studies ranged from 55 to 241, the mean age ranged from 53 to 63 years, the proportion of male patients ranged from 62% to 79%, and the mean MELD score ranged from 15 to 28. Most studies were done in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, and most were conducted in Europe or Asia. In each of the studies, urine samples were collected shortly after enrollment. In addition, urine IL18 and NGAL measurements were obtained using research-based assays, with the exception of the ARCHITECT platform (Abbott) used in Treeprasertsuk et al 25, which is a standardized clinical platform for urine NGAL measurement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies

| Study, Year | Country | Enrollment Period | Biomarkers Assessed | Study Measures | Patient Setting | No. Patients | Age (yrs) | Male (%) | MELD Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ariza, 2015 | Spain | Dec 2011 –July 2014 | IL18, NGAL | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis with Acute Decompensation | 55 | 58 | 78 | 23 |

| Barreto, 2014 | Spain | Nov 2011 – Mar 2013 | NGAL | Prognosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis with Bacterial Infections | 132 | 58 | 70 | 21 |

| Belcher, 2014 | US | Aug 2009 – Dec 2011 | IL18, NGAL | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis with AKI | 188 | 55 | 71 | 26 |

| Fagundes, 2012 | Spain | Jan 2009 – Apr 2011 | NGAL | Diagnosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis | 241 | 60 | 63 | 18 |

| Gungor, 2014 | Turkey | June 2010 – Oct 2011 | NGAL | Prognosis | Patients with Cirrhosis | 64 | 63 | NR | 211 |

| Qasem, 2014 | Egypt | July 2012 – Dec 2012 | IL18, NGAL | Diagnosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis | 160 | 53 | 64 | 19 |

| Treeprasertsuk, 2015 | Thailand | May 2011 – Dec 2013 | NGAL | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis with AKI-prone Conditions | 121 | 57 | 62 | 15 |

| Tsai, 2013 | Taiwan | June 2006 – Dec 2007 | IL18 | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Hospitalized Patients with Severe Sepsis in ICU | 168 | 56 | 79 | 28 |

NR, not reported

MELD-Na Score was reported

Study Quality and Publication Bias

Study quality is reported in Supporting Table 1. All studies used a prospective study design and avoided inappropriate exclusions. Five studies enrolled patients consecutively, while the others did not specify the manner of enrollment. Applicability concerns existed for three studies that enrolled patients in the intensive care unit or that enrolled patients with bacterial infection or acute decompensation of cirrhosis. No studies used a prespecified cutoff, but rather determined optimal cutoffs using ROC curve analysis. All studies used an immunoassay to measure biomarker levels.

Funnel plots were generated to assess publication bias (Supporting Figure 1). The funnel plots were not markedly asymmetric. Additionally, publication bias was not detected using Egger’s regression model (urine IL18 for the diagnosis of ATN, p = 0.32; urine NGAL for the diagnosis of ATN, p = 0.32; urine IL18 for predicting all-cause mortality, p = 0.35; urine NGAL for predicting all-cause mortality, p = 0.51).

Urine IL18 and NGAL for Diagnosis of ATN

Six studies used urine biomarkers to differentiate ATN from other types of kidney impairment in patients with cirrhosis. Of these, four studies used urine IL18 and five studies used urine NGAL (Supporting Table 2). The prevalence of ATN varied from 26% to 35%. Three studies used the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria for kidney impairment, two studies used serum creatinine with a higher threshold than the AKIN criteria, and one study used a combined HRS/ATN definition. The definitions of kidney impairment and ATN used are shown in Supporting Table 3.

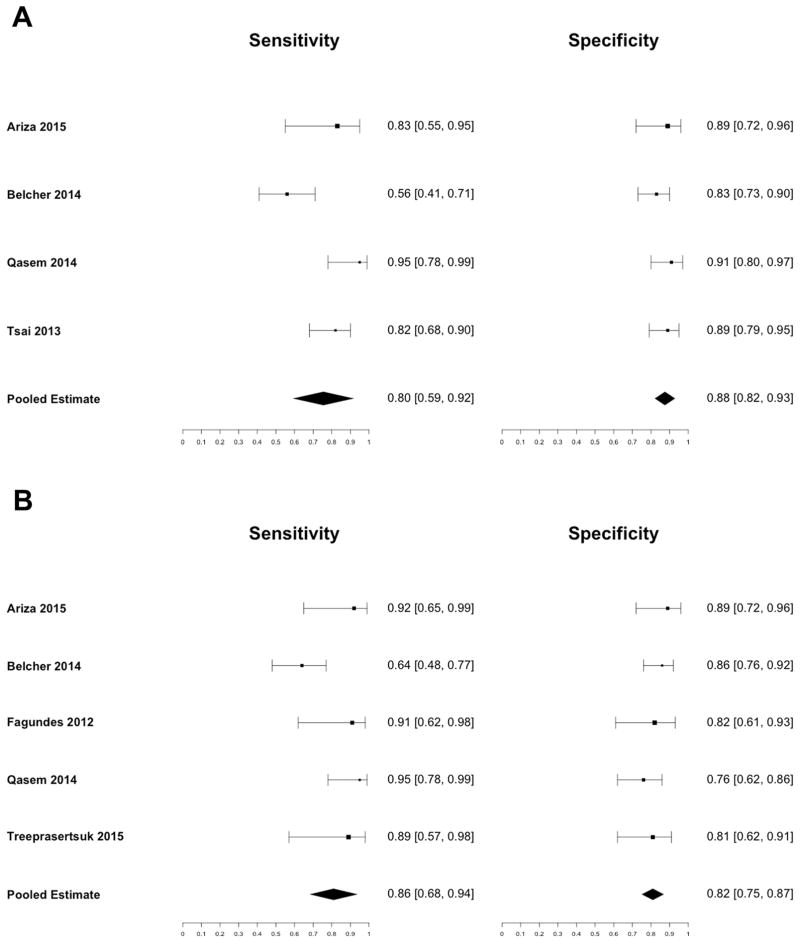

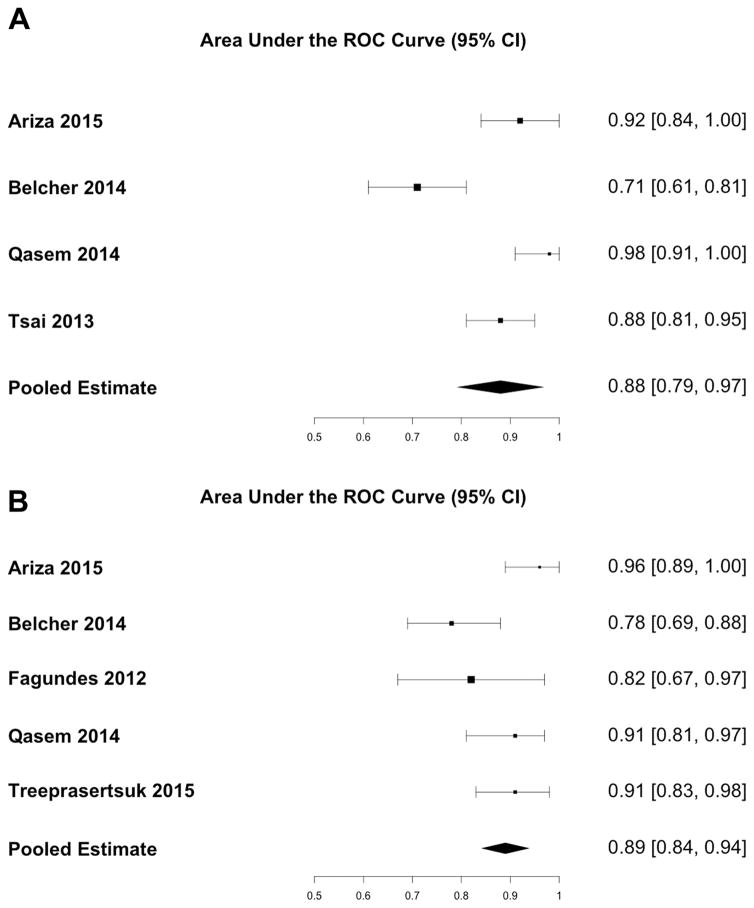

The pooled sensitivity for diagnosis of ATN for urine IL18 was 0.80 (95% CI: 0.59 – 0.92) and the pooled specificity was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.82 – 0.93) (Figure 2a). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.88 (95% CI: 0.79 – 0.97) (Figure 3a). The pooled sensitivity for urine NGAL was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68 – 0.94), and the pooled specificity was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.75 – 0.87) (Figure 2b). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.84 – 0.94) (Figure 3b). There was high heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 90%, p < 0.01) for urine IL18, and moderate heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 61%, p = 0.04) for urine NGAL. Each study identified optimal cutoffs for urine IL18 and NGAL concentration. The reported cutoffs for IL18 and NGAL to diagnose ATN varied considerably from 54 pg/mL to 1109 pg/mL and 137 ng/mL to 365 ng/mL, respectively.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity of (A) Urine IL18 and (B) Urine NGAL for Diagnosis of ATN

Figure 3.

AUC of (A) Urine IL18 and (B) Urine NGAL for Diagnosis of ATN

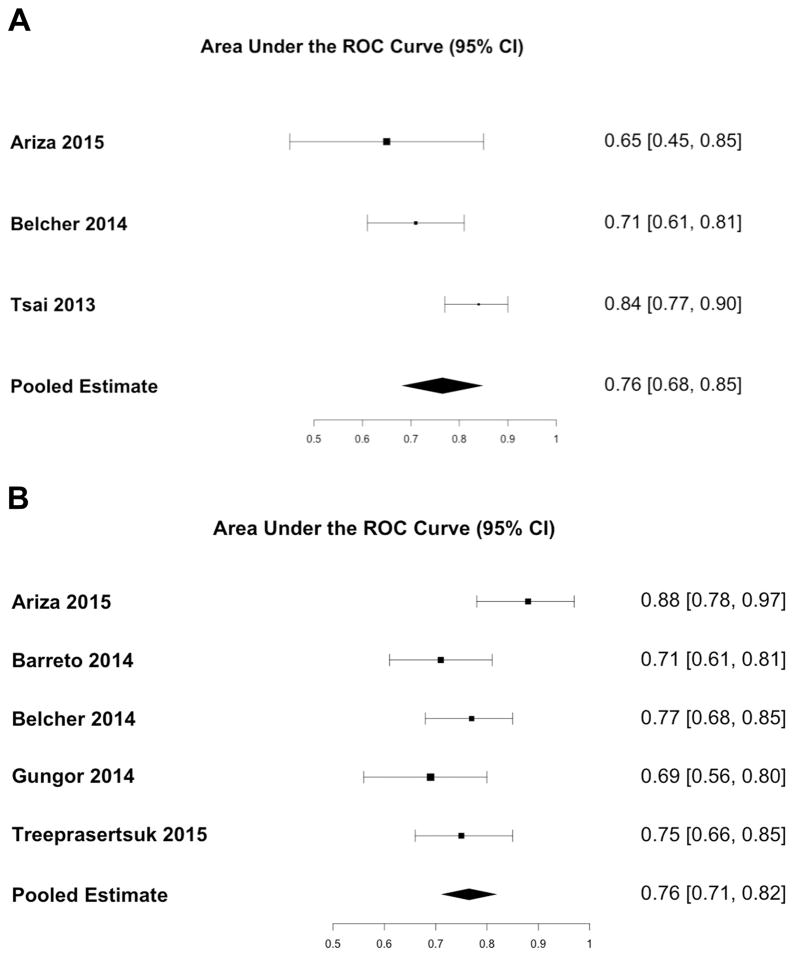

Urine IL18 and NGAL for Prediction of Mortality

Three studies assessed the accuracy of urine IL18 and five studies assessed the accuracy of urine NGAL for predicting all-cause mortality (Supporting Table 4). One study followed patients during hospitalization, and the other five studies followed patients one to six months after discharge. The number of patients followed ranged from 51 to 168. The overall mortality during follow-up ranged from 14% to 65%.

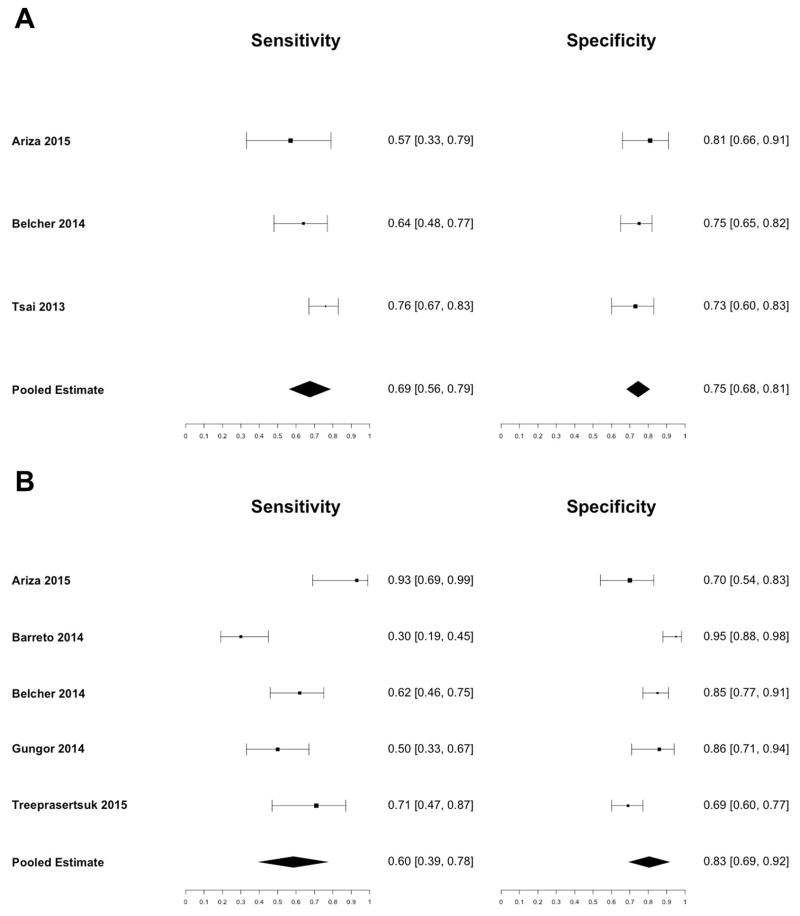

The pooled sensitivity for urine IL18 was 0.69 (95% CI: 0.56 – 0.79) and the pooled specificity was 0.75 (95% CI: 0.68 – 0.81) (Figure 4a). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.68 – 0.85) (Figure 5a). The pooled sensitivity for urine NGAL was 0.60 (95% CI: 0.39 – 0.78), and the pooled specificity was 0.83 (95% CI: 0.69 – 0.92) (Figure 4b). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.71 – 0.82) (Figure 5b). There was moderate heterogeneity between studies for both urine IL18 (I2 = 68%, p = 0.04) and urine NGAL (I2 = 51%, p = 0.08). The prognostic cutoff values for urine IL18 and NGAL concentration varied considerably from 53 pg/mL to 299 pg/mL and 72 ng/mL to 287 ng/mL, respectively.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity and Specificity of (A) Urine IL18 and (B) Urine NGAL for Predicting All-Cause Mortality

Figure 5.

AUC of (A) Urine IL18 and (B) Urine NGAL for Predicting All-Cause Mortality

DISCUSSION

One of the main challenges for physicians caring for patients hospitalized with complications of cirrhosis is unraveling the cause of severe AKI, particularly differentiating between HRS and ATN.31, 32 Serum creatinine is not helpful in this regard, and renal biopsies are usually not performed because of high risk due to marked coagulation abnormalities in patients with advanced cirrhosis. The inability to make the distinction between HRS and ATN is critical, as treatments differ considerably. HRS may be reversed with restoration of renal perfusion, through vasoconstrictor therapy plus intravenous albumin, while patients with ATN may be treated with dialysis or combined liver-kidney transplantation. Furthermore, the most aggressive therapies, such as transplantation, should be reserved for patients with the highest risk for progressive renal dysfunction and death.

In the last few years, there has been an increasing interest in assessing the potential usefulness of renal biomarkers in this setting and a number of studies have been published with this objective.15–25 The rationale for using biomarkers in the differential diagnosis between ATN and functional kidney impairment, particularly HRS, is straightforward. Biomarkers of kidney injury should be increased in the urine of patients with ATN, but not in those with HRS, a condition of functional kidney impairment due to arterial vasoconstriction, which lacks structural injury to kidney tubular cells.11, 32, 33

The current meta-analysis assesses the performance of two kidney injury biomarkers, IL18 and NGAL, for diagnosis and prognosis of AKI in patients with cirrhosis. IL18 is a mediator of inflammation and ischemic injury in many organs. In the kidney, tubular cells and interstitial macrophages produce IL18 in response to injury.34, 35 Human studies indicate that IL18 is a biomarker of tubular damage because urinary levels of IL18 are markedly increased in patients with ATN, whereas they are low in patients with AKI due to volume depletion and in patients without AKI. A number of prospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that urinary IL18 can predict the clinical onset of AKI moderately well across a wide range of clinical settings, including critically ill patients, patients undergoing cardiac surgery, and patients receiving kidney transplantation.36, 37 Moreover, urinary IL18 has also been shown to have a relatively good ability to predict the need for renal replacement therapy and mortality during hospitalization.9, 13, 36, 37

NGAL is a 25 kDa protein that derives from the lipocalin-2 gene.38 Under normal conditions, NGAL is very abundant in the cytosolic granules of neutrophils but barely expressed in other cells. However, as a result of tissue injury, NGAL is overexpressed in a variety of human tissues, including the kidneys, liver, and lungs.38–41 In patients with kidney injury, NGAL is detected in the urine before an increase in serum creatinine. Moreover, urine levels are markedly increased in AKI due to ATN but only minimally increased in AKI due to prerenal failure.12 In AKI due to ATN, urine NGAL appears to derive mainly from increased expression in epithelial cells of the distal nephron. However, it may also derive from filtration and decreased reabsorption due to proximal tubular injury.42 A number of large prospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that urine NGAL is a good diagnostic biomarker of AKI, specifically ATN. Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated the accuracy of NGAL for predicting the clinical onset of AKI in a number of patient settings, such as ICU, cardiopulmonary bypass surgery, and kidney transplantation, as well as for predicting renal replacement therapy and mortality.43, 44

Although several meta-analyses evaluate NGAL and IL18 in various clinical settings, none of these meta-analyses investigate the diagnostic and prognostic performance of IL18 and NGAL in patients with cirrhosis and AKI. This topic is of clinical relevance because, as mentioned previously, patients with cirrhosis frequently develop HRS, a severe functional form of AKI, not seen in patients without liver disease.11, 32 Making the distinction between HRS and ATN is very relevant for therapeutic purposes, particularly in candidates for liver transplantation.5, 6, 11, 31 The results of the current meta-analysis show that both urinary NGAL and IL18 have good sensitivity and specificity for identifying ATN in patients with cirrhosis and therefore differentiating ATN from HRS (IL18: 0.80 and 0.88; NGAL: 0.86 and 0.82, respectively). These values are similar or even better than those reported in different patient settings.13, 36, 37 Moreover, the AUC for diagnosis of ATN was 0.88 and 0.89 for IL18 and NGAL, respectively; these values are higher than those found in most studies in different patient settings.37, 43 As expected, values of biomarkers were lower in patients with HRS and higher in patients with ATN. Considering that both IL18 and NGAL are inflammatory mediators, it is worth mentioning that the origin of IL18 and NGAL found in the urine of patients with cirrhosis may not be exclusively related to kidney injury but also to the intensive systemic inflammation characteristic of patients with cirrhosis.45 Moreover, in addition to their ability to detect ATN, urine IL18 and NGAL predicted short-term mortality after AKI moderately well (IL18: AUC, 0.76; NGAL: AUC, 0.76). Furthermore, the assays used to measure both urine IL18 (Bio-Rad, MBL) and NGAL (Bio-Rad, BioPorto, BioVendor, Abbott) are commercially available worldwide.

This meta-analysis has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there were differences in study characteristics (e.g., age, gender, MELD score, sample collection time, biomarker assay), which may have contributed to the heterogeneity observed in the results.46 However, the number of available studies limited our ability to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analyses and meta-regression. Second, the criteria used to define ATN were slightly different across studies, and as expected, kidney biopsies were not performed in any study to confirm ATN. Third, duration of follow-up was different among studies so mortality at a specific time point could not be assessed. Fourth, we could not determine the ideal diagnostic and prognostic cutoffs for IL18 and NGAL because we did not have the raw data to perform ROC curve analysis. Finally, although these biomarkers are able to differentiate between structural (ATN) and functional (PRA and HRS) causes of kidney impairment, they are unable differentiate between PRA and HRS. However, other biomarkers such as FENa have been shown to distinguish HRS from PRA and ATN.21 Therefore, urine IL18 and NGAL used in conjunction with FENa may be able to make the clinically important distinction between ATN, HRS, and PRA. Despite these limitations, our meta-analysis provides the most comprehensive assessment and robust evidence to date of the accuracy of urine biomarkers for assessing AKI and prognosis in patients with cirrhosis.

In summary, this meta-analysis suggests that both urinary IL18 and NGAL are of value for distinguishing between AKI due to ATN and HRS. Moreover, both biomarkers show predictive value for all-cause mortality in patients with cirrhosis. These findings indicate that incorporating urine IL18 and NGAL into clinical decision-making has the potential to more accurately guide treatment. Furthermore, these biomarkers can also potentially be used to enrich clinical trials of AKI. For example, in a HRS trial, urine IL18 and NGAL could be used as diagnostic biomarkers to preferentially enroll individuals with HRS and reduce misclassification with ATN. In addition, they could be used as prognostic biomarkers to identify patients likely to reach trial end points (such as all-cause mortality). Further studies with standardized diagnostic criteria are needed for FDA and EMA qualification of these biomarkers for drug development and to identify relevant cutoffs for clinical application.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Ming-Hung Tsai for providing additional unpublished information from his study.

Grant Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant K24DK090203 awarded to Chirag Parikh. Chirag Parikh is also named a co-inventor on the IL18 patent licenced to the University of Colorado (no financial value).

This work was also supported by a grant awarded to Pere Ginès from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI12/00330), integrated in the Plan Nacional I+D+I and co-funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and European Regional Development Fund FEDER. Pere Ginès is the PI for the Agencia de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris I de Recerca (AGAUR) 2014 SGR 708. Pere Ginès is a recipient of an ICREA Academia Award. Isabel Graupera was supported by a grant from Plan Estatal I+D+I and Instituto Carlos III (Rio Hortega fellowship).

Abbreviations

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- PRA

prerenal azotemia

- ATN

acute tubular necrosis

- HRS

hepatorenal syndrome

- IL18

interleukin 18

- LCN2 or NGAL

lipocalin 2

- QUADAS-2

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2

- AUC

area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve

- AKIN

Acute Kidney Injury Network

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Pere Ginès declares that he has received research funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Grifols S.A., and Sequana Medical. He has participated on Advisory Boards for Noorik, Ikaria, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Promethera, and Sequana Medical. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Author Contributions: JP and XA drafted the report. CRP acquired funding for the study. All authors designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fagundes C, Barreto R, Guevara M, et al. A modified acute kidney injury classification for diagnosis and risk stratification of impairment of kidney function in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59(3):474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piano S, Rosi S, Maresio G, et al. Evaluation of the Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59(3):482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia–Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):2064–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.22605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allegretti AS, Ortiz G, Wenger J, et al. Prognosis of Acute Kidney Injury and Hepatorenal Syndrome in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Prospective Cohort Study. International journal of nephrology. 2015;2015:108139. doi: 10.1155/2015/108139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angeli P, Gines P, Wong F, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites. Gut. 2015;64(4):531–7. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadim MK, Durand F, Kellum JA, et al. Management of the critically ill patient with cirrhosis: A multidisciplinary perspective. Journal of hepatology. 2016;64(3):717–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Llahi M, Guevara M, Torre A, et al. Prognostic importance of the cause of renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(2):488–96. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, et al. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;57(2):753–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koyner JL, Parikh CR. Clinical utility of biomarkers of AKI in cardiac surgery and critical illness. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8(6):1034–42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05150512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alge JL, Arthur JM. Biomarkers of AKI: a review of mechanistic relevance and potential therapeutic implications. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2015;10(1):147–55. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12191213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durand F, Graupera I, Gines P, et al. Pathogenesis of Hepatorenal Syndrome: Implications for Therapy. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2016;67(2):318–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickolas TL, O'Rourke MJ, Yang J, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a single emergency department measurement of urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for diagnosing acute kidney injury. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;148(11):810–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-11-200806030-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Gebretsadik T, et al. Elevated urinary IL-18 levels at the time of ICU admission predict adverse clinical outcomes. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010;5(8):1497–505. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09061209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nickolas TL, Schmidt-Ott KM, Canetta P, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic stratification in the emergency department using urinary biomarkers of nephron damage: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;59(3):246–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verna EC, Brown RS, Farrand E, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts mortality and identifies acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012;57(9):2362–70. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2180-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagundes C, Pepin MN, Guevara M, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as biomarker in the differential diagnosis of impairment of kidney function in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2012;57(2):267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai MH, Chen YC, Yang CW, et al. Acute renal failure in cirrhotic patients with severe sepsis: value of urinary interleukin-18. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2013;28(1):135–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gungor G, Ataseven H, Demir A, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in prediction of mortality in patients with hepatorenal syndrome: a prospective observational study. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2014;34(1):49–57. doi: 10.1111/liv.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barreto R, Elia C, Sola E, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin predicts kidney outcome and death in patients with cirrhosis and bacterial infections. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qasem AA, Farag SE, Hamed E, et al. Urinary biomarkers of acute kidney injury in patients with liver cirrhosis. ISRN nephrology. 2014;2014:376795. doi: 10.1155/2014/376795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belcher JM, Sanyal AJ, Peixoto AJ, et al. Kidney biomarkers and differential diagnosis of patients with cirrhosis and acute kidney injury. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):622–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.26980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, et al. Urinary biomarkers and progression of AKI in patients with cirrhosis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9(11):1857–67. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09430913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhaddad OM, Alsebaey A, Amer MO, et al. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin: A New Marker of Renal Function in C-Related End Stage Liver Disease. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2015;2015:815484. doi: 10.1155/2015/815484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ariza X, Sola E, Elia C, et al. Analysis of a urinary biomarker panel for clinical outcomes assessment in cirrhosis. PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0128145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treeprasertsuk S, Wongkarnjana A, Jaruvongvanich V, et al. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a diagnostic and prognostic marker for acute kidney injury (AKI) in hospitalized cirrhotic patients with AKI-prone conditions. BMC gastroenterology. 2015;15:140. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;155(8):529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, England ; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. xxi.p. 649. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. New York: Wiley; 2000. p. xii.p. 373. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychological methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.European Association for the Study of the L. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2010;53(3):397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gines P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(13):1279–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gines P. Management of Hepatorenal Syndrome in the Era of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Telipressin and Beyond. Gastroenterology. 2016 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Siegmund B, et al. Neutrophil-independent mechanisms of caspase-1- and IL-18-mediated ischemic acute tubular necrosis in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2002;110(8):1083–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu H, Craft ML, Wang P, et al. IL-18 contributes to renal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2008;19(12):2331–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parikh CR, Mishra J, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Urinary IL-18 is an early predictive biomarker of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Kidney Int. 2006;70(1):199–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001527. Epub 2006/05/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Guo W, Zhang J, et al. Urinary interleukin 18 for detection of acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013;62(6):1058–67. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakraborty S, Kaur S, Guha S, et al. The multifaceted roles of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) in inflammation and cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1826(1):129–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borkham-Kamphorst E, Drews F, Weiskirchen R. Induction of lipocalin-2 expression in acute and chronic experimental liver injury moderated by pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1beta through nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2011;31(5):656–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu MJ, Feng D, Wu H, et al. Liver is the major source of elevated serum lipocalin-2 levels after bacterial infection or partial hepatectomy: a critical role for IL-6/STAT3. Hepatology. 2015;61(2):692–702. doi: 10.1002/hep.27447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ariza X, Graupera I, Coll M, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is a biomarker of acute-on-chronic liver failure and prognosis in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori K, Lee HT, Rapoport D, et al. Endocytic delivery of lipocalin-siderophore-iron complex rescues the kidney from ischemia-reperfusion injury. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115(3):610–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI23056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haase M, Bellomo R, Devarajan P, et al. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in diagnosis and prognosis in acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2009;54(6):1012–24. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang A, Cai Y, Wang PF, et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for acute kidney injury with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care. 2016;20:41. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1212-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S131–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Endre ZH, Pickering JW, Walker RJ, et al. Improved performance of urinary biomarkers of acute kidney injury in the critically ill by stratification for injury duration and baseline renal function. Kidney Int. 2011;79(10):1119–30. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.