Abstract

In the past 15 years, the cost of sequencing a genome has plummeted. Consequently, the number of sequenced bacterial genomes has exponentially increased, and methods for natural product discovery have evolved rapidly to take advantage of the wealth of genomic data. This review highlights applications of genome mining software to compare and organize large-scale data sets and methods for identifying unique biosynthetic pathways amongst the thousands of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP) gene clusters. We also discuss a small number of the many RiPPs discovered in the years 2014–2016.

Introduction

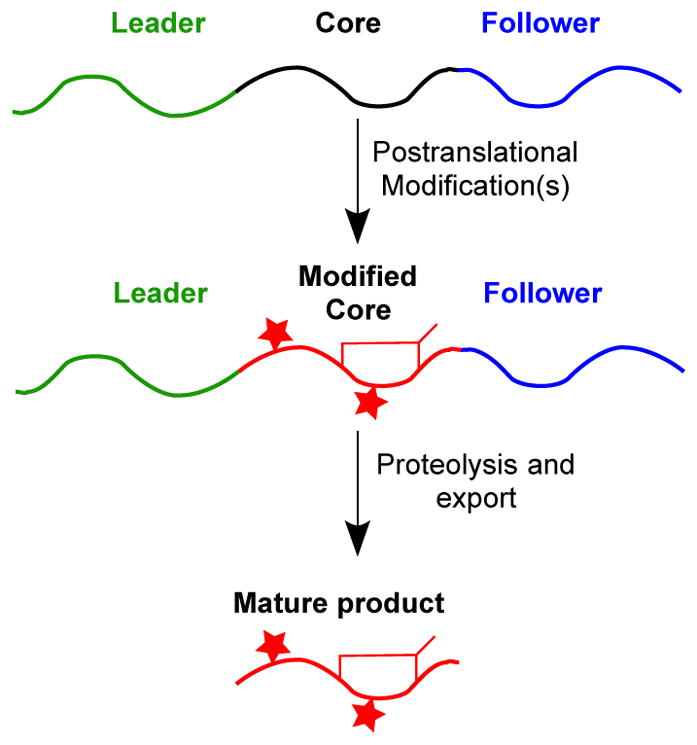

Peptides are an area of increasing attention for providing solutions to therapeutic challenges, including disrupting “undruggable” protein-protein interactions [1] and fighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria [2]. In this context, the family of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) has seen a growing interest. As illustrated in Figure 1, RiPPs follow a seemingly simple biosynthetic logic – a core peptide is fused to a leader peptide, a follower peptide, or both that aid installation of post-translational modifications (PTMs). Following modification of the core peptide, the leader and/or follower regions are removed to reveal the final product [3]. Various different RiPP classes are defined by the types of PTMs installed on the core peptide, as described in detail elsewhere [4], and the biosynthetic enzymes leverage a variety of mechanisms to install the wealth of PTMs [3,5]. The extensive modification of the core peptide endows RiPPs with advantages over linear peptides, such as resistance to proteolysis and a lower entropic cost of target binding. Some RiPPs have advanced to clinical trials or therapeutic use, such as the lanthipeptide duramycin to combat cystic fibrosis [6], the thiopeptide LFF571 to battle Clostridium difficile infection [7], and the conopeptide Prialt to treat neuropathic pain [8]. While engineering strategies have begun to allow optimization of RiPPs, discovery and characterization of novel RiPP biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) remains the primary means for attaining RiPPs with new or improved activity or unusual chemical structures.

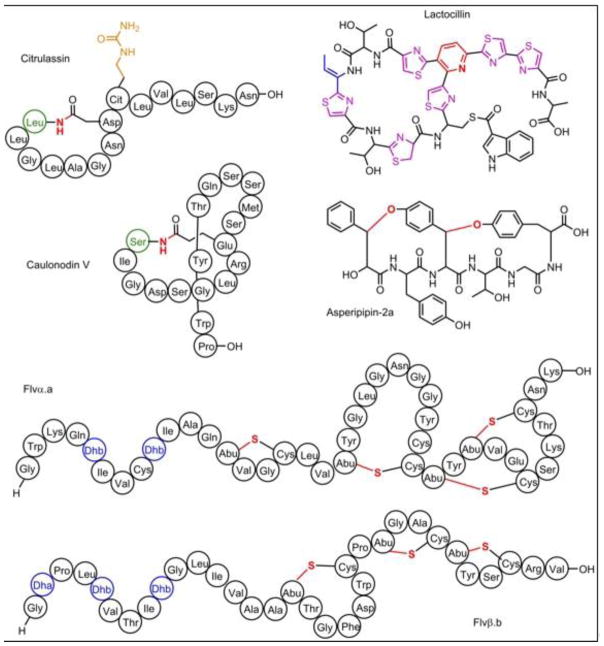

Figure 1.

General biosynthetic pathway for RiPPs. Note that the precursor peptides can contain a leader peptide, a follower peptide, or both.

The discovery methods for RiPPs have undergone a revolution in recent years due to the explosion of available genomic data [9–11] and the plummeting of the price of a sequenced genome [12]. Software enables identification of a gene cluster in silico and the natural product is then accessed through a combination of structure prediction, heterologous expression, or host manipulation – a “bottom-up” approach. At the same time, software facilitates top-down discovery, where the desired biological activity is first identified followed by sequencing of the producer’s genome. This interplay of classic discovery methodologies, such as activity-based screening, with genomic data and a variety of genome mining strategies has led to rapid expansion in the characterized numbers, chemical diversity, and activities of RiPPs. This review outlines the application of new genome mining software, highlights the discovery of RiPP classes in fungi, and notes a few of the many noteworthy additions to RiPP families attained through either a bottom-up or top-down approach. For biosynthetic pathways and classification schemes we refer to a recent comprehensive review [4].

Large scale RiPP identification using automated genome mining software

Many tools exist for RiPP genome mining [13,14]. The most commonly used methods are BLAST [15], BAGEL [16], antiSMASH [17], ClusterFinder [18], and RiPP-PRISM [19]. Many of these tools identify complete clusters of various RiPP families through comparison to a training set of known RiPP clusters, leveraging combinations of hidden Markov models, “rules” for precursor peptide identification (e.g., short open reading frames [ORFs] rich in residues that are acted on by the associated biosynthetic enzymes), and comparison to databases of known RiPP sequences. The identification of precursor peptides remains a challenge, and a recent approach called RODEO leverages a machine-learning based approach for this purpose [20].

BAGEL, antiSMASH, and BLAST were combined to explore the genomes of 211 anaerobic bacteria, long believed to be non-prolific producers of secondary metabolites, for RiPP-encoding clusters [21]. Over 25% of these bacteria were shown to encode at least one RiPP, and 10% encode only RiPP secondary metabolites. This analysis suggests that RiPPs are widespread and present in many under-characterized secondary metabolomes.

An assessment of the enrichment of RiPPs in the human microbiota has also been reported [22]. First, BGCs in 2,430 reference genomes of organisms known to be present in the human microbiota were identified using ClusterFinder, yielding >44,000 BGCs. These clusters were further classified into secondary metabolite families using antiSMASH (e.g., RiPPs, or products from nonribosomal peptide synthetases [NRPS] and and polyketide synthases [PKS]). More than 14,000 BGCs were thus identified. Comparison to BGCs that were found in metagenomic data acquired from 752 sites on healthy humans as part of the Human Microbiome Project revealed that 3,118 of these BGCs were present in healthy humans. RiPP clusters were found to be slightly enriched in human associated genomes compared to non-human associated genomes, and were observed in all sampled areas of the microbiome (e.g., oral cavity, skin, gut, airways) [22]. A previously unknown thiopeptide, termed lactocillin (Figure 3), and its associated biosynthetic gene cluster was thus discovered. Biochemical characterization revealed an unmodified C-terminus (thiopeptides C-termini are frequently modified to esters or amides [23]), strong bioactivity against Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis, but surprisingly weak activity against associated commensal organisms, suggesting a specific range of action [22].

Figure 3.

Structures of RiPPs characterized from a bottom-up discovery approach. Note that the tail of citrulassin is threaded through the ring similar to caulonodin V; however, to show the citrulline side chain it is shown unthreaded. Post-translational modifications are colored as follows. Red: bonds formed during cyclization, blue: dehydration, purple: thiazol(in)es/oxazol(in)es, orange: citrulline, green: novel Ser/Leu residue at position 1 in caulonodin V and citrulassin. Dhb: dehydrobutyrine, Abu: α-aminobutyric acid, Cit: citrulline.

Combining structural prediction and genome mining to identify unique RiPP clusters

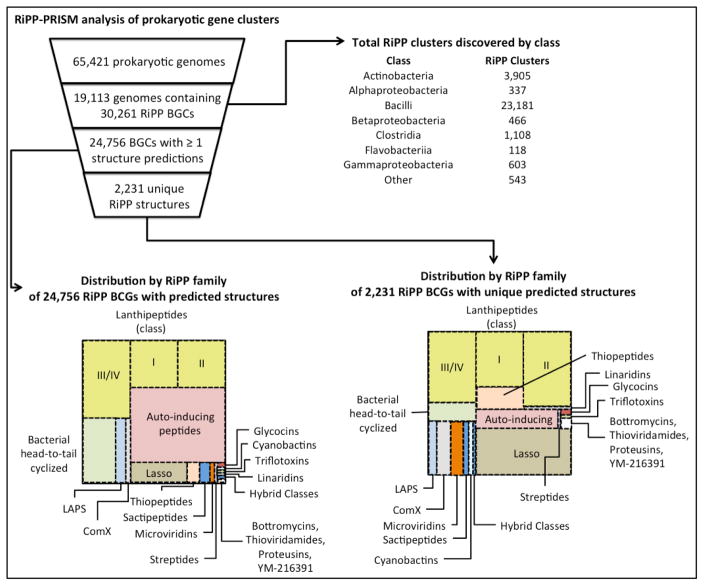

RiPP-PRISM identifies gene clusters, precursor peptides, and leader peptide cleavage sites, and predicts a library of potential structures of the final product. As illustrated in Figure 2, the authors applied the program to analysis of the 65,421 prokaryotic genomes available in NCBI. Approximately 20% of these genomes were determined to encode RiPPs, spread across a phylogenetically diverse range, and the relative abundance of different RiPPs was assessed. Moreover, the structural prediction capability of RiPP-PRISM allowed an analysis of the number of unique RiPP products in each class as a proxy for chemical diversity within each family of RiPPs. The analysis suggests that the majority of RiPP chemical diversity, even for known families, remains undiscovered. The same conclusion was reached in an analysis of 830 Actinobacteria genomes for just lanthipeptide gene clusters [24]. This survey made abundantly clear that the biosynthetic enzymes are much more diverse than previously realized, with identification of hybrids of the four previously recognized lanthipeptide classes. In addition, many tailoring enzymes of unknown function were observed that likely add to the chemical diversity of the final products.

Figure 2.

RiPP-PRISM genome mining results of 65,421 prokaryotic genomes. The area of the rectangles in the bottom half of the picture correspond to the relative number of clusters found. Figure generated using data from [19].

Shared biosynthetic machinery across RiPP families

The Enzyme Function Initiative’s Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFN-EST) allows users to visualize sequence relationships between individual members of a large protein family [25]. A tool that allows a similar analysis on the basis of genomic context, known as a genome neighborhood network (GNN), is also available [25]. Since some of the enzymes installing PTMs are shared across multiple RiPP families, these tools can both help identify the function of a RiPP-associated enzyme and map out members of a family that are not well characterized.

For example, analysis of the diversity of the YcaO cyclodehydratase family of enzymes (InterPro IPR003776, D protein) was performed using the EFI-EST tool [26]. These enzymes convert Ser into oxazoline and/or Cys into thiazoline during biosynthesis of various RiPP families including thiopeptides, microcins, linear azol(in)e-containing peptides (LAPs), bottromycins, and cyanobactins [4]. Bioinformatic analyses of members of the YcaO family were performed including cluster and precursor peptide identification. Use of the EFI-EST tool with the YcaO domains demonstrated they clustered largely by RiPP family or sub-family; for example, members involved in making microcin B17-like products clustered together, those involved in cyanobactin synthesis formed another cluster, etc. Of particular interest, several large clusters were identified without characterized members, and examination of the associated gene clusters revealed novel putative tailoring enzymes, truncated cyclodehydratases, and new precursor peptide families, illustrating the potential of using a characterized RiPP biosynthetic enzyme as a handle to bioinformatically discover unexplored RiPP chemical space [26].

Examples of bottom-up RiPP discovery

Lanthipeptides are characterized by the presence of dehydroalanine and/or dehydrobutyrine as well as at least one macrocycle formed by a thioether linkage [4]. Recent genome mining for lanthipeptides has been fruitful, leading to the discovery of bicereucin [27], the cerecidins [28], and stackepeptin [29], among others. An interesting BGC was discovered in Ruminococcus flavefaciens FD-1, a commensal bacterium occurring in the rumen of animals, that encoded two putative class II lanthipeptide synthetases and twelve putative lanthipeptide precursor peptides. Of the precursor peptides, four shared significant homology with one another and with known lipid II-binding lanthipeptides of two-component lantibiotics (α-peptides). The remaining eight precursors, presumed to form the partner β-component, were much more divergent. Heterologous expression of combinations of the precursor peptides and modifying enzymes revealed that each enzyme recognized a specific set of substrates and could install the characteristic dehydrations and thioether crosslinks. Bioactivity analysis of paired α + β peptides (Figure 3) revealed that four of the pairs were weakly active against an aerobic and two anaerobic Gram-positive species [30]. These findings support the idea that the multicomponent flavecins may have evolved to engage specific target bacteria in the complex microbiome of ruminants [30]. Further analysis of 225 ruminant-living bacteria using BAGEL3 and antiSMASH suggests that their microbiome may be a rich source of lanthipeptides and other RiPPs [31].

The RiPP-PRISM analysis indicates that lasso peptides are a large family of chemically diverse natural products. Biochemical characterization of lasso peptides has indeed born out that assertion as many of the original “rules” for lasso precursor identification have been greatly expanded [20,32]. Lasso peptides are characterized by a knotted structure where the C-terminus is threaded through a macrocycle formed by a covalent bond between the N-terminal amine and an aspartate or glutamate side chain [4]. A PSI-BLAST analysis using a known lasso peptide-processing enzyme revealed 102 putative lasso peptides from 87 proteobacteria. Twelve of these were heterologously produced and characterized [33]. It was also noted that Caulobacter sp. K31 was a particularly rich source of lasso peptides, termed caulonodins (Figure 3), encoding three putative clusters with a total of seven precursor peptides [34]. Three of these precursor peptides contained the typical glycine residue at the start of the core peptide; however, the core peptide of four others started with unusual serine or alanine residues. Heterologous expression in E. coli followed by characterization using NMR and mass spectrometry revealed that all four could be produced. Similar workflows have led to the discovery of xanthomonins [35], lasso peptides with a previously uncharacterized ring size, and paeninodin [36], a phosphorylated lasso peptide. Recent application of RODEO to the lasso peptides revealed >1,300 compounds in the genomes [20], of which six were characterized including citrulassin, a citrulline-containing family member (Figure 3), which represents a novel PTM in RiPPs. Citrulassin also further expanded the amino acids found at the first position with a Leu, and the RODEO analysis suggests that members exist with all amino acids except Pro at position 1 [20].

Fungi also produce a variety of RiPPs; however, genome mining is particularly challenging in fungi since gene transcripts are typically processed prior to protein production. Most fungal RiPPs have therefore been characterized through a top-down approach, leading to the identification of the amatoxins [37], phallotoxins [37], virotoxins (all reviewed in [38]), and more recently the epichloëcyclins [39], the ustiloxins [40], and the phomopsins [41]. Increasing knowledge of the biosynthetic enzymes associated with fungal RiPPs has revealed that the ustiloxins and phomopsins are widespread in the dikarya subkingdom [41,42]. Using in silico methods, Umemura and colleagues identified a predicted fungal RiPP in Aspergillus flavus that they termed asperipin-2a. The product was subsequently isolated from the native producer and characterized by NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3) [42].

Examples of top-down RiPP discovery aided by genomic data

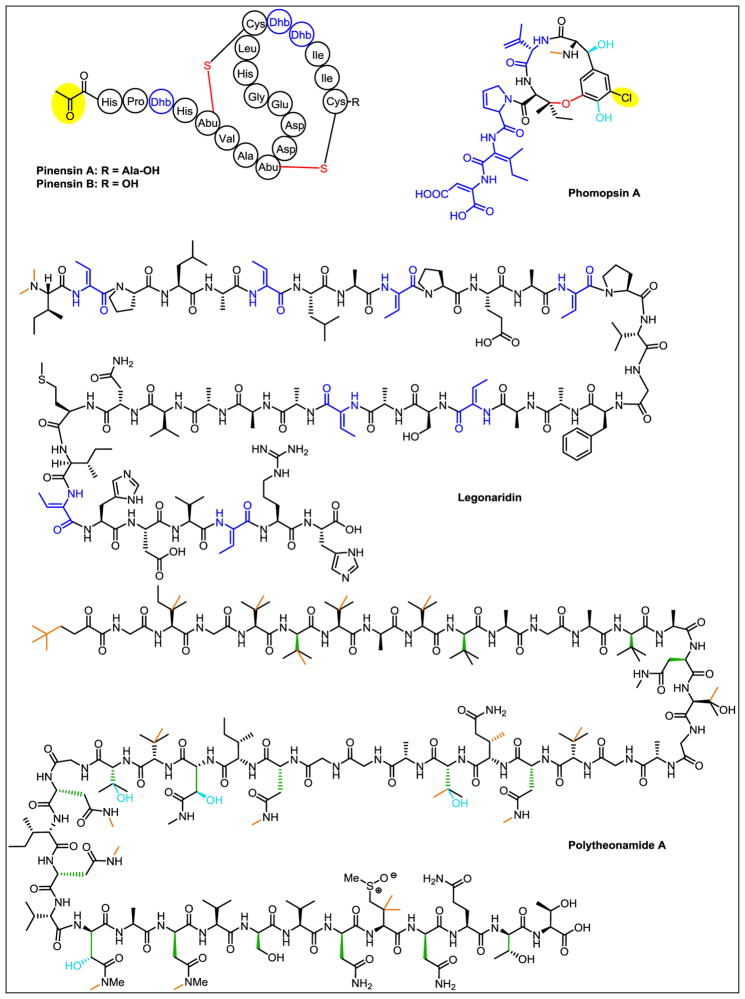

Using activity-guided fractionation, Müller and colleagues reported the first antifungal lanthipeptides, isolated from the Gram-negative proteobacteria Chitinophaga pinensis [43]. The two-component pinensins (Figure 4) were characterized via mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. The precursor gene was identified through a BLAST search of the producing organism’s genome using the core peptide sequence as a query, revealing a single ORF that encoded the pinensin A sequence. The gene cluster was then manually annotated around the precursor and the associated genes characterized by homology-based comparison to known enzymes. Three surprising insights emerged from the cluster. First, typical class I lanthipeptides contain a dehydratase, termed a LanB, that activates the hydroxyl residues of select serine/threonine residues by glutamylation, and then eliminates glutamate to form dehydroalanine/dehydrobutyrine. However, the pinensin dehydratase is “split,” similar to the dehydratases found in the thiopeptides [44], where PinB1 has homology to the glutamylation domain of full-length LanBs and PinB2 has homology to the Glu elimination domain. Cyclization is performed by a typical LanC-like cyclase, the enzyme that forms the thioether rings in lanthipeptides, but whereas class I lanthipeptides generally use a LanT transporter protein to export the natural product and a separate LanP protease to remove the leader peptides, proteolytic processing of the pinensins is accomplished through the action of a bifunctional LanT that both exports and proteolyses the peptide. Third, a single precursor gene encodes both components of the two-component system, suggesting a proteolytic step may be required for formation of the second component [43].

Figure 4.

Structures of RiPPs discovered via a genomics-aided top-down approach. Posttranslational modifications are colored as follows. Red: bonds formed during cyclization, blue: dehydrogenation (phomopsin A) or dehydration, green: epimerization, cerulean: hydroxylation, purple: thiazol(in)es/oxazol(in)es, orange: methylation, yellow oval: other post-translational modification. Dhb: dehydrobutyrine, Abu: α-aminobutyric acid.

The linaridins are a small but complex class of RiPPs [4], comprising cypemycin, grisemycin, and the most recently described member, legonaridin (Figure 4). Legonaridin was discovered through metabolite screening of a Streptomyces strain discovered in Legon, Ghana [45]. Analysis using the natural product peptidogenomics (NPP) tool [46] allowed determination of peptide sequences associated with the natural product. The producing organism’s genome was analyzed using antiSMASH, and a precursor peptide matching the peptide reads from NPP was identified. The structure was predicted based on the gene cluster and comparison to cypemycin, followed by spectroscopic verification. A BLAST search of the precursor peptide identified five homologs in other Streptomyces strains with similar gene clusters, suggesting this may be a new class of linaridins characterized by a free carboxy C-terminus rather than an aminovinyl-cysteine, as found in other characterized linaridins [45].

The structure of polytheonamides A and B was first described in 1994 (Figure 4) [47,48]. At the time, it was assumed these complex, 48-residue peptides were synthesized NRPS enzymes. However, subsequent work revealed the presence of a gene encoding a ribosomal peptide whose primary sequence matched that of polytheonamide A, and a cluster encoding potential tailoring enzymes was identified around the precursor gene [49]. Heterologous coexpression studies of the precursor peptide with surrounding genes, including a putative N-methyl transferase, amino acid epimerase, and dehydratase, verified that genes in the cluster indeed encoded enzymes that modified the precursor peptides. This gene cluster encodes proteins to perform an unprecedented 48 modifications – 17 carbon methylations, eight nitrogen methylations, four hydroxylations, one dehydration, and 18 amino acid epimerizations [50].

Other notable recent top-down RiPP discoveries include the first-in-class streptide, containing a carbon-carbon bond formed between lysine and tryptophan [51] and penisin, a lanthipeptide with activity against Gram-negative bacteria [52].

Conclusions

Sophisticated genome mining tools and the explosion in available genomic data has revolutionized RiPP discovery, allowing bottom-up characterization of novel RiPPs, even if they are not produced by their native organism or when the native organism is not culturable. At the same time, these tools have enabled BGC identification for top-down discovery. At present, identifying new RiPP families from genomic data, identifying those RiPP families with too few members to build a statistically representative model, and annotating the often-short precursor peptides are remaining challenges. Furthermore, the bottom-up discovery approach sometimes leads to new compounds without a readily identifiable activity given the wide array of potential functions for RiPPs, and the vast number of identified clusters presents a new challenge of choosing clusters worthy of further characterization. Structural prediction software, such as RiPP-PRISM, or clustering of biosynthetic enzymes into those characterized versus uncharacterized via the EFI-EST, provide two potential solutions. The availability of databases for characterized RiPP biosynthetic gene clusters, including MiBIG [53], Bactibase [54], and the Atlas of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (IMG-ABC) [55], will also aid in virtually de-replicating clusters. Further work will undoubtedly continue to refine the structure prediction function of genome mining software, expand the RiPP families the programs can identify, and refine methodology for identifying RiPP clusters in fungi and other more complex organisms. With these developments, RiPPs can be fully explored as lead compounds for next generation therapeutics.

Highlights.

Genome mining software rapidly identifies RiPP gene clusters from many families.

Such software has enabled surveys of RiPP abundance and chemical diversity.

Much of RiPP chemical diversity remains uncharacterized.

Discovery of new bioactivities and new chemical modifications in RiPPs continues.

Acknowledgments

Our work on RiPPs is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37 GM058822 to W.A.V. and F31 GM113486 to K.J.H.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Studies of particular interest to RiPP genome mining reported in the past 2 years have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Tsomaia N. Peptide therapeutics: Targeting the undruggable space. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;94:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortega MA, van der Donk WA. New Insights into the Biosynthetic Logic of Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptide Natural Products. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnison PG, Bibb MJ, Bierbaum G, Bowers AA, Bugni TS, Bulaj G, Camarero JA, Campopiano DJ, Challis GL, Clardy J, et al. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:108–160. doi: 10.1039/c2np20085f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truman AW. Cyclisation mechanisms in the biosynthesis of ribosomally synthesised and post-translationally modified peptides. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2016;12:1250–1268. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.12.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitlin PL, Boyle MP, Guggino WB, Molina L. A Phase I Trial of Intranasal Moli1901 for Cystic Fibrosis. Chest. 2004;125:143–149. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullane K, Lee C, Bressler A, Buitrago M, Weiss K, Dabovic K, Praestgaard J, Leeds JA, Blais J. Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial To Compare the Safety and Efficacy of LFF571 and Vancomycin for Clostridium difficile Infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1435–1440. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04251-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teichert RW, Olivera BM. Natural products and ion channel pharmacology. Futur Med Chem. 2010;2:731–744. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziemert N, Alanjary M, Weber T. The evolution of genome mining in microbes – a review. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:988. doi: 10.1039/c6np00025h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann BO, van Lanen SG, Baltz RH. Microbial genome mining for accelerated natural products discovery : is a renaissance in the making ? J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;41:175–184. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler MS, Blaskovich MAT, Owen JG, Cooper MA. Old dogs and new tricks in antimicrobial discovery. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;33:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden EC. The $1,000 genome. Nature. 2014;507:294–295. doi: 10.1038/507294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medema MH, Fischbach MA. Computational approaches to natural product discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:639–648. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber T, Kim HU. The secondary metabolite bioinformatics portal: Computational tools to facilitate synthetic biology of secondary metabolite production. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2016;1:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madden T. The NCBI Handbook. 2. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2013. The BLAST Sequence Analysis Tool; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Heel AJ, de Jong A, Montalbán-López M, Kok J, Kuipers OP. BAGEL3: Automated identification of genes encoding bacteriocins and (non-)bactericidal posttranslationally modified peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:448–453. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Müller R, Wohlleben W, et al. AntiSMASH. 3.0-A comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Cimermancic P, Medema MH, Claesen J, Kurita K, Brown LCW, Mavrommatis K, Pati A, Godfrey PA, Koehrsen M, Clardy J, et al. Insights into Secondary Metabolism from a Global Analysis of Prokaryotic Biosynthetic Gene Clusters. Cell. 2014;158:412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034. Analysis of a diverse set of bacterial genomes illustrates RiPP biosynthesis is widespread. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Skinnider MA, Johnston CW, Edgar RE, Dejong CA, Merwin NJ, Rees PN, Magarvey NA. Genomic charting of ribosomally synthesized natural product chemical space facilitates targeted mining. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:E6343–E6351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609014113. A new algorithm for annotation of an unprecendented number of RiPP families in genomic data was applied to over 65,000 prokaryotic genomes. The structural prediction function of the software was used to estimate the relative diversity of the RiPP families. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Tietz JI, Schwalen CJ, Patel PS, Maxon T, Blair PM, Tai H-C, Zakai UI, Mitchell DA. A new genome mining tool redefines the lasso peptide biosynthetic landscape. Nat Chem Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2319. In press A new bioinformatics tool that facilitiates the discovery of novel RiPPs. It uses machine learning to address the challenge of identifying RiPP precursor peptides. The tool was used to comprehensively describe the lasso peptide class encoded in the genomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Letzel A, Pidot SJ, Hertweck C. Genome mining for ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides ( RiPPs ) in anaerobic bacteria. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-983. Using multiple genome mining techniques, the authors establish that anaerobic bacteria are a rich source of RiPPs, contrary to the prior anticipation that these oxygen-starved organisms do not produce many secondary metabolites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Donia MS, Cimermancic P, Schulze CJ, Brown LCW, Martin J, Mitreva M, Clardy J, Linington RG, Fischbach MA. A Systematic Analysis of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in the Human Microbiome Reveals a Common Family of Antibiotics. Cell. 2014;158:1402–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.032. Focusing on BGCs found at the intersection of genomic data and metagenomic data from healthy microbiome samples, the authors identify abundant natural product classes present in the human microbiome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Just-Baringo X, Albericio F, Álvarez M. Thiopeptide antibiotics: Retrospective and recent advances. Mar Drugs. 2014;12:317–351. doi: 10.3390/md12010317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Zhang Q, Doroghazi JR, Zhao X, Walker MC, van der Donk Wa, van der Donka WA. Expanded natural product diversity revealed by analysis of lanthipeptide-like gene clusters in Actinobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:4339–4350. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00635-15. This study shows that the great majority of genome-encoded lanthipeptides are structurally very different from known family members. Since most lanthipeptides in clinical development are from Actinobacteria, this finding suggest that many therapeutically interesting compounds remain to be discovered. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerlt JA, Bouvier JT, Davidson DB, Imker HJ, Sadkhin B, Slater DR, Whalen KL. Enzyme function initiative-enzyme similarity tool (EFI-EST): A web tool for generating protein sequence similarity networks. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2015;1854:1019–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox CL, Doroghazi JR, Mitchell DA. The genomic landscape of ribosomal peptides containing thiazole and oxazole heterocycles. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:778. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huo L, van der Donk WA. Discovery and characterization of bicereucin, an unusual D-amino acid-containing mixed two-component lantibiotic. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5254–5257. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Zhang L, Teng K, Sun S, Sun Z, Zhong J. Cerecidins, novel lantibiotics from bacillus cereus with potent antimicrobial activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:2633–2643. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03751-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jungmann NA, Van Herwerden EF, Hügelland M, Süssmuth RD. The Supersized Class III Lanthipeptide Stackepeptin Displays Motif Multiplication in the Core Peptide. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:69–76. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X, Van Der Donk WA. Structural Characterization and Bioactivity Analysis of the Two-Component Lantibiotic Flv System from a Ruminant Bacterium. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azevedo AC, Bento CBP, Ruiz JC, Queiroz MV, Mantovani HC. Distribution and genetic diversity of bacteriocin gene clusters in rumen microbial genomes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:7290–7304. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01223-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegemann JD, Zimmermann M, Xie X, Marahiel MA. Lasso Peptides: An Intriguing Class of Bacterial Natural Products. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1909–1919. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegemann JD, Zimmermann M, Zhu S, Klug D, Marahiel MA. Lasso Peptides From Proteobacteria: Genome Mining Employing Heterologous Expression and Mass Spectrometry. Pept Sci. 2013;100:27–30. doi: 10.1002/bip.22326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann M, Hegemann JD, Xie X, Marahiel MA. Characterization of caulonodin lasso peptides revealed unprecedented N-terminal residues and a precursor motif essential for peptide maturation. Chem Sci. 2014;5:4032–4043. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hegemann JD, Zimmermann M, Zhu S, Steuber H, Harms K, Xie X, Marahiel MA. Xanthomonins I–III: A new class of lasso peptides with a seven-residue macrolactam ring. Angew Chemie - Int Ed. 2014;53:2230–2234. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paeninodin P, Zhu S, Hegemann JD, Fage CD, Zimmermann M, Xie X, Linne U, Marahiel MA. Insights into the Unique Phosphorylation of the Lasso Peptide Paeninodin. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:13662–13678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallen HE, Luo H, Scott-craig JS, Walton JD. Gene family encoding the major toxins of lethal Amanita mushrooms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19097–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707340104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang S, Zhou Q, He Z, Luo T, Zhang P, Cai Q, Yang Z, Chen J, Chen Z. Cyclopeptide toxins of lethal amanitas: Compositions, distribution and phylogenetic implication. Toxicon. 2016;120:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson RD, Lane GA, Koulman A, Cao M, Fraser K, Fleetwood DJ, Voisey CR, Dyer JM, Pratt J, Christensen M, et al. A novel family of cyclic oligopeptides derived from ribosomal peptide synthesis of an in planta-induced gene, gigA, in Epichloë endophytes of grasses. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015;85:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye Y, Minami A, Igarashi Y, Izumikawa M, Umemura M, Nagano N, Machida M, Kawahara T, Shin-ya K, Gomi K, et al. Unveiling the Biosynthetic Pathway of the Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptide Ustiloxin B in Filamentous Fungi. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;3:1–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding W, Liu W-Q, Jia Y, Li Y, van der Donk WA, Zhang Q. Biosynthetic investigation of phomopsins reveals a widespread pathway for ribosomal natural products in Ascomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3521–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522907113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42**.Nagano N, Umemura M, Izumikawa M, Kawano J, Ishii T, Kikuchi M, Tomii K, Kumagai T, Yoshimi A, Machida M, et al. Class of cyclic ribosomal peptide synthetic genes in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2016;86:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.010. First report of a RiPP biosynthetic pathway described first in silico and then characterized experimentally. The study also establishes the prevalence of related RiPPs in filamentous fungi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Mohr KI, Volz C, Jansen R, Wray V, Hoffmann J, Bernecker S, Wink J, Gerth K, Stadler M, Müller R. Pinensins: The First Antifungal Lantibiotics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:11254–11258. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500927. First characterized lanthipeptide from a Bacteroidete and first antifungal lanthipeptide. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hudson GA, Zhang Z, Tietz JI, Mitchell DA, van der Donk WA. In Vitro Biosynthesis of the Core Scaffold of the Thiopeptide Thiomuracin. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:16012–16015. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rateb ME, Zhai Y, Ehrner E, Rath CM, Wang X, Tabudravu J, Ebel R, Bibb M, Kyeremeh K, Dorrestein PC, et al. Legonaridin, a new member of linaridin RiPP from a Ghanaian Streptomyces isolate. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:9585–9592. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01269d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kersten RD, Yang Y-L, Xu Y, Cimermancic P, Nam S-J, Fenical W, Fischbach MA, Moore BS, Dorrestein PC. A mass spectrometry-guided genome mining approach for natural product peptidogenomics. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:794–802. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamada T, Sugawara T, Matsunaga S, Fusetani N. Polytheonamides, unprecedented highly cytotoxic polypeptides, from the marine sponge theonella swinhoei: 1. Isolation and component amino acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:719–720. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamada T, Sugawara T, Matsunaga S, Fusetani N. Polytheonamides, unprecedented highly cytotoxic polypeptides from the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei: 2. Structure elucidation. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:609–612. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freeman MF, Gurgui C, Helf MJ, Morinaka BI, Uria AR, Oldham NJ, Sahl H, Matsunaga S, Piel J. Metagenome Mining Reveals Polytheonamides as Posttranslationally Modified Ribosomal Peptides. Science. 2012;338:387–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1226121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Freeman MF, Helf MJ, Bhushan A, Morinaka BI, Piel J. Seven enzymes create extraordinary molecular complexity in an uncultivated bacterium. Nat Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nchem.2666. In press. The authors demonstrate through heterologous expression that seven enzymes are responsible for introducing 44 modifications during the biosynthesis of polytheonamides. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Schramma KR, Bushin LB, Seyedsayamdost MR. Structure and biosynthesis of a macrocyclic peptide containing an unprecedented lysine-to-tryptophan crosslink. Nat Chem. 2015;7:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2237. Discovery of an entirely new RiPP class. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baindara P, Chaudhry V, Mittal G, Liao LM, Matos CO, Khatri N, Franco OL. Characterization of the Antimicrobial Peptide Penisin, a Class Ia Novel Lantibiotic from Paenibacillus sp. Strain A3. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:580–591. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01813-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medema MH, Kottmann R, Yilmaz P, Cummings M, Biggins JB, Blin K, de Bruijn I, Chooi YH, Claesen J, Coates RC, et al. Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:625–631. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hammami R, Zouhir A, Hamida J, Ben Fliss I. BACTIBASE : a new web-accessible database for bacteriocin characterization. 2007;6:6–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadjithomas M, Chen IA, Chu K, Ratner A, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Huang J, Reddy TBK, Cimermanc P. IMG-ABC : A Knowledge Base To Fuel Discovery of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters and Novel Secondary Metabolites. 2015;6:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00932-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]