Abstract

Human filarial infections are a leading cause of morbidity in the developing world. While a small arsenal of drugs exists to treat these infections, there remains a tremendous need for the development of additional interventions. Recent genome sequences and transcriptome analyses of filarial nematodes have provided novel biological insight and allowed for the prediction of novel drug targets as well as potential vaccine candidates. In this review, we discuss the currently available data, insights gained into the metabolism of these organisms, and how the filaria field can move forward by leveraging these data.

Keywords: filaria, parasitic nematodes, genomics, transcriptomics

Introduction

Nematodes cause the most common parasitic infections in humans, and the tissue-dwelling filarial worms produce the most severe pathology associated with these infections. Current control programs, universally based upon the mass distribution of a small arsenal of drugs targeting microfilaria loads and transmission, will not be sufficient on their own to eliminate lymphatic filariae by 2020, especially where loasis is co-endemic. The programs are also threatened by the difficulties of repeatedly achieving high coverage rates necessary for elimination when using the currently available drugs, as well as by the specter of drug resistance to the limited selection of drugs now being used. No method to permanently sterilize the adult female worms or to kill the filarial parasite exists, sounding the call for additional research to discover novel macrofilaricidal drug candidates. Many filarial worm species carry a Wolbachia endosymbiont that can be eliminated through antibiotic treatments, interfering with development, reproduction, and survival of the worms within the host, a clear indicator that the Wolbachia are crucial for survival of the parasite. Recent advances in the sequencing of filarial genomes and transcriptomes, as well as those of their bacterial endosymbionts, have contributed greatly to our better understanding of the biology of these parasites. They have also enabled the identification of novel drug targets and potential vaccine candidates.

Current state of genome and transcriptome sequencing efforts

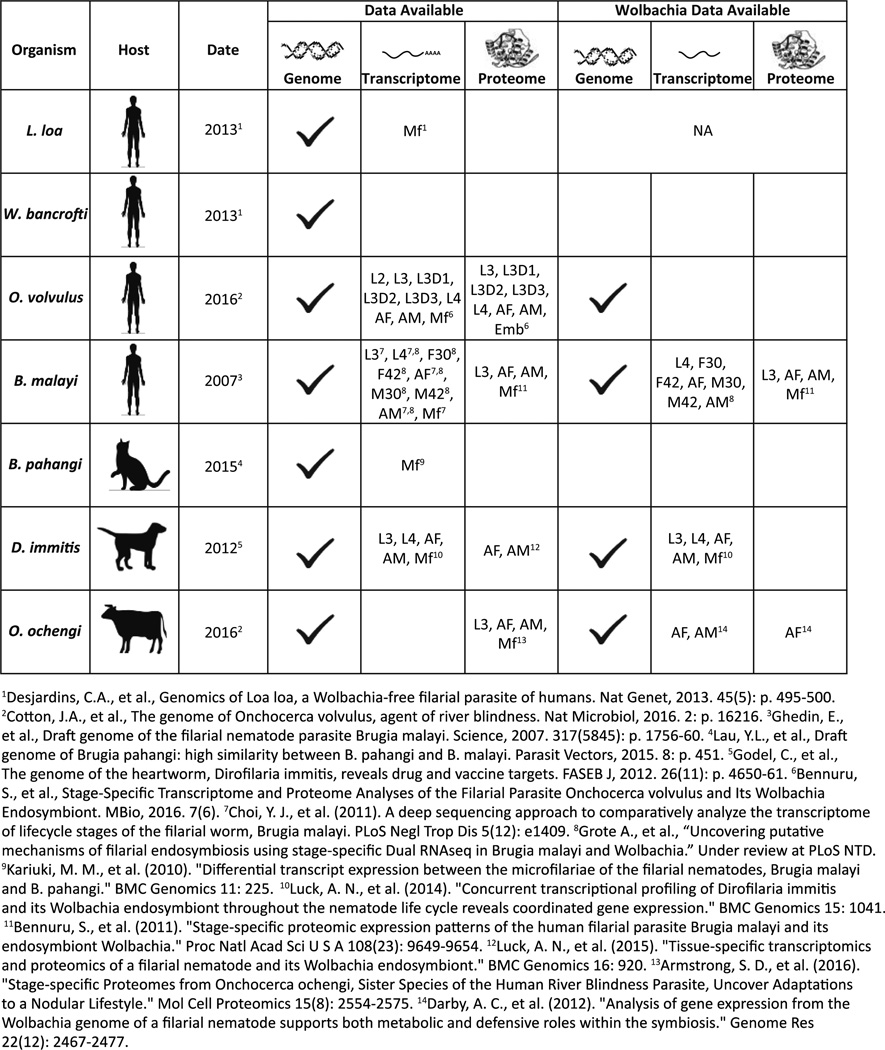

Filarial nematodes currently infect up to 54 million people worldwide, with many millions more at risk for infection, representing the leading cause of morbidity in the developing world [1, 2]. Lymphatic filariasis, due to Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori, represents the leading cause of morbidity. It is followed by onchocerciasis and loasis, caused respectively by Onchocerca volvulus and Loa loa. The study of these important pathogens is made particularly difficult due to the inability to maintain most of these parasites outside of the human host, requiring extraction from human blood or tissue. B. malayi remains the only human filarial parasite that can be maintained in small laboratory animals [3–6]. Thus, the generation of high- quality genomes and transcriptomes is essential to interpret critical proteomic information, and to study the unique biology of these different filarial parasites. To this end, sequencing efforts have led to the first high-quality genome assemblies with reconstructions of whole chromosomes for both O. volvulus [7] and B. malayi (WormBase.org) [Manuscript in preparation]. A number of draft genomes also exist for the other filarial nematodes including L. loa, W. bancrofti, B. pahangi, D. immitis, and O. ochengi [8–10] [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Summary of Omics data available for filarial parasites.

The genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data available for filarial nematodes with sequenced genomes. Stages for which transcriptomic and proteomic data exist are listed in each box, L2, L3, L4: larval stages, L3D1: L3 day 1 of molting, L3D2: L3 day 2 of molting, L3D3: L3 day 3 of molting. F30: juvenile female 30 days post infection (dpi), F42: juvenile female 42 dpi, M30: juvenile male 30 dpi, M42: juvenile male 30 dpi, AF: adult female, AM: adult male, Mf: microfilaria, Emb: embryo.

Genome Features

Filarial gene content

The evolution of a parasitic lifestyle is associated with a reduction in genome size, reflective of the parasite’s dependency on its host [11]. Sequenced genomes of filarial nematodes such as B. malayi and O. volvulus encode 13,865 and 12,143 genes, respectively, a little more than half the number of protein coding genes present in the C. elegans genome [7, 12]. Meanwhile, the genomes of L. loa and W. bancrofti are predicted to encode a slightly larger number, at 14,261 and 14,496-15,075, respectively [8]. While this means we can expect to find a number of reduced protein families, we would also expect to see expansion of gene families involved in the adaptation to parasitism. For example, as compared to the other filariae, the L. loa genome was found enriched for a number of protein domains including the pyridoxamine 5’-phosphate oxidases that synthesize vitamin B, as well as for chemoreceptors, potentially indicative of complex interactions between L. loa and its environment [8]. W. bancrofti was found to be enriched for domains related to cellular adhesion and the extracellular matrix, potentially involved in either mediating fibrosis associated with lymphatic filariasis, or establishment of infection in the lymphatics [8]. In O. volvulus using a comparative analysis approach it was found that the gene family encoding the alpha subunit of the enzyme collagen prolyl 4- hydroxylase (C-4PH alpha), an enzyme involved in collagen synthesis, was significantly expanded as compared to other filariae [7] Similarly, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) show a remarkable expansion in O. volvulus, with the Srx and Srsx GPCR families among the most duplicated gene families in the genome [7]. Conversely, the nuclear hormone receptor (NHR) gene family was found to be particularly depleted in filarial worms as compared to free living nematodes like the Caenorhabditis—B. malayi has 50 and O. volvulus has 24 classical NHRs and 8 orphan receptors, as compared to C. elegans which has over 270 NHRs. Interestingly, the O. volvulus ecdysone receptor (OVOC9104) was also gained at the base of the filarial lineage. Ecdysone and related hormones regulate molting and metamorphosis in arthropods, leading to speculation that this gain in NHRs may be an adaptation to the insect host [7].

Gene synteny among nematode genomes

Comparisons of the genome organization of the free living nematode C. elegans to that of parasitic nematodes reveal that while local synteny—or conservation of gene order—has been lost, linkage has been conserved on chromosomal units [7, 12, 13]. Among the filariae there is a relatively high level of conservation of gene order, with 40% of L. loa genes being syntenic with B. malayi genes and 13% relative to W. bancrofti [8]. However, because nearly all syntenic breaks occurred at scaffold ends, it is likely that the true level of synteny is actually much higher [8]. A study to analyze macro- and microsynteny across nematodes found that intra- rather than inter-chromosomal rearrangements were favored [13]. The relative syntenic conservation values were also shown to be consistent with the estimated evolutionary distance to C. elegans. For example, the syntenic conservation score is 0.752 between C. elegans and C. briggsae, and 0.508 between C. elegans and B. malayi. Whole genome analysis of B. malayi and B. pahangi revealed high synteny, with a genome coverage range of 70-75%, with 90% of predicted genes in B. pahangi containing orthologs in B. malayi [9]. The existence of syntenic blocks reveals a likely functional constraint on genome evolution [13].

The evolution of sex chromosomes

One unique observation from these sequenced genomes and the assembly of full filaria chromosomes is the presence of a Y chromosome in both B. malayi and O. volvulus, unlike the model nematode C. elegans which has an XX/X0 sex determinism [14]. Evidence for a Y chromosome in these organisms has existed for almost 30 years, however, until recently, we had been unable to determine its sequence, gene content and origin [15, 16]. It was hypothesized that the nematode ancestor had a Y chromosome that was eventually degraded and lost in C. elegans, requiring sex-determining genes to jump to autosomes. The absence of a Y chromosome in most other nematodes suggests the X0 sex chromosome system is the ancestral state, and the XY system is a derived, neo-XY system that evolved from the fusion of the X chromosome and an autosome [17, 18]. Currently, Y chromosomes have also been observed in 10 other filarial nematodes besides B. malayi and O. volvulus: Dirofilaria immitis, Brugia pahangi, Wuchereria bancrofti, Onchocerca gutturosa, Onchocerca lienalis, Onchocerca tarsicola, Onchocerca armilatta, Onchocerca dukei, Onchocerca ochengi, and Onchocerca gibsoni [15, 16, 19–23]. However, these observations were made through karyotyping; B. malayi and O. volvulus are the only genomes of sufficient quality to observe the sequence of the Y chromosome. In nematodes where the Y chromosome determines sex, it is hypothesized that the selection against chromosomal rearrangements in the X chromosome would be relaxed.

Wolbachia, the bacterial endosymbiont

Wolbachia genomes and lateral gene transfer

No discussion of filarial genomes and transcriptomes is complete without a mention of Wolbachia, the bacterial endosymbiont of most filaria. Wolbachia are intracellular bacteria found in both arthropods such as insects, mites, and crustaceans, as well as filarial nematodes. There is currently only one species in the genus Wolbachia, Wolbachia pipientis, divided into six supergroups, A-F. Wolbachia found in filarial nematodes belong to supergroups C and D [24]. The first filarial Wolbachia genome to be sequenced was that of the Wolbachia endosymbiont of B. malayi (wBm) of supergroup D, which was found to be 1.1 Mb with 805 protein coding genes [25], smaller than previously described Wolbachia genomes. Interestingly, the genome maintains complete pathways for the synthesis of heme, riboflavin, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), as well as pathways for de novo synthesis of purines and pyrimidines. This observation led to the speculation that because the B. malayi genome is lacking these complete synthesis pathways, wBm may be provisioning the nematode with these essential cofactors [12, 25]. Sequencing of the Wolbachia genome of O. ochengi (wOo) of supergroup C revealed a genome 11% smaller than that of wBm, with several regions of microsynteny with wBm, but generally large differences in chromosomal organization [26]. The wOo genome is the most reduced of all Wolbachia genomes sequenced to date, having lost features such as transposable elements; the genome contains only six insertion sequence (IS) copies, and has no group II introns, unlike the wBm genome and the Wolbachia of insects where they are found in high abundance [25]. The recent sequencing of the Wolbachia endosymbiont of O. volvulus (wOv) also of supergroup C, revealed a genome with 785 predicted protein-coding genes, nearly identical to wOo, but about 1,937-bp larger [7]. A large number of SNPs (4,400) were also identified, of which 57 may result in functional differences, potentially involved in the interaction of the endosymbionts with their filarial and/or mammalian hosts (i.e. cattle and humans) [7].

Nuclear Wolbachia transfers (nuwts) have been identified in all Wolbachia-colonized and Wolbachia-free filarial genomes sequenced thus far, suggesting that all filarial nematodes were once colonized by Wolbachia, with some having since lost the endosymbiont [8, 27]. The size and predicted functionality of these transfers are quite variable between filarial nematodes. While L. loa (a Wolbachia-free filaria) contains some presumably old nuwts, none are over 500 bp and there is no evidence that any of them are expressed and functional [8]. Conversely, nuwts are prevalent in two of the other Wolbachia-free filarial nematodes, Acanthocheilonema viteae and O. flexuosa, with average sizes of 173.6 and 158.9 bp respectively [27]. Of the 49 Wolbachia-like DNA sequences found in the A. viteae genome, 30 were detected by qRT-PCR to be expressed; of the 114 Wolbachia-like sequences found in the O. flexuosa genome, 56 were expressed [27]. There is also evidence of horizontal gene transfer in the genomes of filaria that have maintained Wolbachia infection, such as B. malayi. The B. malayi genome contains 227 Wolbachia genes and gene fragments, 32 of which contain open reading frames and thus potentially encode functional proteins. Evidence for the expression of 4 of the transfers was found in the B. malayi transcriptome [28]. The O. volvulus genome contains 531 putative nuwts, all but 4 of which were fragmented. While these 4 transfers were confirmed by amplification, cloning, and sequence verification of the Wolbachia-nematode junction, the nuwts in O. volvulus appear to be largely nonfunctional [7].

Concurrent transcriptional analysis

In addition to genome analyses, next generation sequencing has enabled the concurrent stage- specific transcriptional profiling of both the filarial nematode and the bacterial endosymbiont. Such studies have been completed in D. immitis, O. ochengi, and B. malayi [26, 29, 30] [Manuscript under review at PLoS NTD]. In all studies, the transcripts for the chaperonin and heat shock proteins including GroEL, GroES, and DnaK were among the most highly expressed. All three studies point to the potential stage-specific provisioning of metabolic products by Wolbachia to the filarial worms as well as correlated pathway expression. A better understanding of the specific mechanisms that define the mutualistic interplay between the filariae and their Wolbachia endosymbiont will facilitate the identification of pathways that could be targeted to ultimately kill the adult worms; such novel macrofilaricidal drugs would complement present MDA efforts to control and eventually eliminate filariasis.

Establishment of infection in the final host

Tissue migration strategies

Serine and cysteine proteases have been identified as integral to host invasion and migration in a number of parasitic nematodes. Trichuris muris—a parasitic nematode of mice—uses serine proteases to break down the mucus barrier of the host intestine to establish infection [31]. Cercarial elastases and trypsin-like serine proteases in Schistosoma mansoni have been shown to play a critical role in tissue invasion of the human host as well as egression from the intermediate snail host, while S. japonicum and Trichobilharzia regenti appear to use the Cathepsin B peptidase for their tissue invasion strategy [31–34]. Analysis of the newly sequenced O. volvulus genome reveals that while there are no cercarial elastase-like enzymes present, there are 8 trypsin-like serine proteases as well as one chymotrypsin-like protease in the genome [7]. Genome-wide analysis of filarial genomes shows that there are four duplications of trypsin-like serine proteases in the filarial nematodes. Analysis of their expression reveals stage-specific regulation wherein the chymotrypsin-like protease is expressed across the larval stages as well as in the microfilaria, while six of the trypsin-like serine proteases show significant upregulation in the adult males. This pattern of expression suggests the importance of trypsin-like proteases in certain stages, such as for O. volvulus adult males that must migrate through subcutaneous tissue of the host to fertilize females that reside in nodules.

Molting

The L3 to L4 molt in filarial parasites occurs immediately upon infection of the mammalian host marking the establishment of infection. Both the B. malayi and O. volvulus genomes contain homologs to most of the genes required for molting in C. elegans, including proteases, NHRs, cuticular collagens, and chitinases [12, 35]. As previously mentioned, analysis of NHRs in the O. volvulus genome revealed significantly fewer NHRs than in C. elegans. Despite this, O. volvulus has maintained orthologs to all 5 C. elegans NHRs exclusively involved in molting and metamorphosis [7]. Unlike C. elegans, the L3 to L4 molt in several filarial nematodes has additionally been shown to be dependent on the activity of CPL-1 and CPZ-1, members of the cathepsin L-like and cathepsin Z-like filarial proteases [36, 37]. Analysis of CPL gene families revealed an expansion of CPL-like enzymes in the filarial clade, and an additional expansion in the O. volvulus genome. Transcriptome analysis in O. volvulus also revealed significant regulation of CPL and CPZ molecules in the L2 and L3 larvae as compared to other stages [35]. Their increased expression in L2 larvae suggests that CPLs and CPZ also play a role in the L2 to L3 molt in the vector, similar to what was described in B. malayi 38].

Signaling

Another component of niche specificity has to do with how parasitic nematodes receive signals from their environments. To begin to understand this process, a genome-wide analysis of GPCRs in free-living and parasitic nematodes was performed [8]. It was found that filarial genomes were lacking a wide array of GPCRs as compared to free-living C. elegans—only the srab, srx, srsx, and srw families were conserved across all nematodes, suggesting that these GPCRs mediate vital nematode functions [8]. In common with other filaria, O. volvulus is missing three of the families present in C. elegans and C. briggsae, including Srj, Sra, and Srb. However, unlike other filaria, O. volvulus contains members of all other GPCR families represented in C. elegans and C. briggsae. We also find that the str family of GPCRs, hypothesized to be involved in the detection of volatiles or odorants, is lacking in all the filaria and other nematodes that live in only aqueous environments [8]. The maintenance of str and other families of GPCRs in O. volvulus that are lacking in other filariae suggests their importance in the O. volvulus lifecycle [7].

Insights into host-parasite interactions

Immunomodulation

Filarial parasites are natural immunomodulators, able to subvert the host immune responses in order to successfully persist in both their human and insect hosts. It is hypothesized that filaria use not only their own innate immune system, but are able to manipulate that of their host [8]. While the exact mechanisms of such manipulation remain largely unknown, genomic analysis has shed light on these processes. A comparative analysis of filarial genomes revealed the presence and expansion of a number of gene families implicated in immunomodulation in L. loa [8]. While adaptive immune molecules such as immunoglobulins and Toll-like receptors are absent in filarial genomes, there is evidence for a primitive Toll-related pathway in many filaria [7, 8]. Other members of the innate immune system of L. loa, B. malayi, and O. volvulus include lectins, galectins, jacalins, as well as scavenger receptors [7, 8, 12]. A number of serpins, small serine protease inhibitors (SPIs), and cystatins that are known to interfere with antigen presentation and processing in T cells, were also found in the genomes of L. loa, O. volvulus, B. malayi, and D. immitis [7, 8, 10, 12, 39]. SPIs also play an important role in controlling the molting process [40] and immune evasion [41]. Notably, the analysis of the O. volvulus genome revealed the presence of 10 additional SPIs beyond the 2 previously identified, Ov-SPI-1 and Ov-SPI-2 [35]. Other potential immune modulators including members of the macrophage migration inhibition (MIF) family and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) homologs have been identified in B. malayi, O. volvulus, L. loa, and D. immitis [7, 8, 10, 12]. In addition, a variety of human cytokine and chemokine mimics or antagonists were identified in filarial genomes [7, 8, 10, 12] So far, no filarial genomes have been found to encode the antibacterial peptidases seen in C. elegans and other non-filarial nematodes [7, 8, 12].

Kinases

Protein kinases, particularly those that are unique to nematodes and distinct from the ones in humans, represent attractive drug targets and their analysis can provide biological insight. A comparison of protein kinases in filarial and non-parasitic nematodes revealed many differences, particularly regarding those involved in meiosis. For example, the genome of L. loa contains the widely conserved TTK kinase (MSP1) involved in eukaryotic meiosis, which is absent in C. elegans. Conversely, filarial nematodes lack the highly conserved CHK-2 kinase, of the RAD53 family found in C. elegans [8]. The B. malayi genome was found to have 205 conventional and 10 atypical protein kinases, of which 142 are essential, based on RNAi evidence in C. elegans [12]. Analysis of protein kinases in O. volvulus revealed 168 kinases without significant human matches [7]. Analysis of the L. loa genome revealed six orthologs to targets of drugs already approved for use in humans, including the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, effective against schistosomes [8]. Initial studies have already shown the distinctive effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib on B. malayi at different stages in the life cycle, including adult males, adult females, L3 larvae, and microfilariae in vitro [42].

Where do we go from here?

Diseases caused by parasitic nematodes constitute the leading cause of morbidity in the developing world. Current microfilaricidal drugs appear to be insufficient for the ultimate goal of control and elimination of these parasitic infections, necessitating a better understanding of the basic biology of these worms and the development of new drugs and vaccines. With the nearly complete filarial genomes and the availability of stage-specific transcriptomic and proteomic data, there now exists a plethora of information and new tools with which to achieve these goals. By using the newly available genomic and transcriptomic data significant progress has already been made towards the identification of novel vaccine and drug targets. Some of these proteins are already the targets of already approved human drugs that have not yet been tested on the filariae but that could potentially be used as new therapies for filarial infections. A computational target-based approach to screen FDA-approved drugs across all World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Classes (WHO ATC) with the potential for use as anthelmintics has led to the identification of 16 O. volvulus proteins likely to be good drug targets; they are mostly enzymes and proteins involved in ion transport and neurotransmission [7].

Identification of novel drug targets

Metabolic potential has been shown to be a critical determinant of a pathogen’s ability to survive in an infected host [43–45]. Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction is a way to determine an organism’s metabolic potential as well as allow for in silico investigation of essential pathways. Flux balance analysis (FBA) is increasingly being used to create draft metabolic networks based on available enzyme annotation data to better understand the metabolic potential of a pathogen [46]. FBA enables the identification of metabolic fluxes that maximize certain functions such as growth potential, using a biomass equation describing the proportion of metabolites required by a system for growth. Metabolic reconstruction has been used to predict enzymes required for growth and virulence of a number of pathogens including Plasmodium falciparum [47], Leishmania major [48], and Toxoplasma gondii [44]. FBA was used for the first time to reconstruct the metabolism of filarial nematodes, comparing the essential reactions in L. loa and O. volvulus and the contribution of Wolbachia. For O. volvulus, only 71 reactions were predicted to be essential, while for L. loa, 112 reactions were predicted to be essential. O. volvulus benefits from Wolbachia contributions to fatty acid metabolism, heme synthesis, and purine and pyrimidine metabolism, which, unlike L. loa, does not require the salvage of precursors or biomass components involved in these pathways. Analysis of purine metabolism reveals that Wolbachia provides an alternate pathway for purine metabolism, whereas L. loa depends exclusively on adenine import. This pathway is an example of how the presence of Wolbachia can change the metabolic chokepoints in filaria and serves to identify selective drug targets [7].

Identification of novel vaccine candidates using immunomics

Newly available genomic and proteomic data for parasitic nematodes is making high-throughput vaccine antigen discovery, known as “immunomics”, now possible [49–52]. This approach allows for profiling of host immune antibody response to candidate parasitic antigens in a high throughput manner. This assay was employed to identify potential vaccine antigens in the genomes of S. mansoni [52, 53], S. Japonicum [50], Necator americanus [51], and for the first time also in the genome of O. volvulus [35]. Criteria for selecting O. volvulus candidate vaccine proteins on the array have included: 1) abundant expression in L3 and molting L3 or in microfilariae, the targets for prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines, respectively [54], 2) predicted secretion based on the presence of a leader sequence or other motifs, containing 0-3 transmembrane domains and below 50 kDa in size (to increase the probability of efficient expression using the cell-free in vitro transcription and translation systems), and 4) not having a significant human match. These selection criteria focused on proteins that are likely to be on the apical surface or secreted by targeted parasites, and are therefore more likely to come into contact with the host immune system [55]. There is evidence that natural immunity against certain parasitic nematodes, including O. volvulus, can be acquired in a few individuals in affected populations; these individuals are known as putatively immune [56]. It has been shown that this immunity is facilitated by a protective immune response against the infective stage (L3) larvae, suggesting that excretory-secretory products and surface proteins of L3 larvae are an important source of protective antigens [56]. The array was screened with sera samples from putatively immune individuals, infected individuals, and control individuals (individuals from non- endemic areas). The IgG1, IgG3 and IgE antibody/antigen recognition profiles were compared to naturally immune individuals and those infected. Elevated cytophilic IgG1 and/or IgG3 responses to L3 antigens were previously shown to be associated with protection [57]. Although IgE antibodies could also be protective [58], we tested IgE responses to reduce the risk that administration of such vaccine candidates in humans could generate atopic responses, an essential requirement for helminth-derived recombinant vaccine antigens [59]. A recent immunomic analysis in O. volvulus led to the identification of six novel vaccine candidates based on IgG1 and/or IgG3 reactivity, with little to no IgE reactivity [35] [Table 1]. Notably, the majority of these candidates are hypothetical, with no known function.

Table 1. Six novel vaccine candidates for O. volvulus.

Table of the six novel vaccine candidates identified by the immunomic analysis in O. volvulus. Expression values in Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (RPKMs) are shown for each developmental stage.

| Expression (RPKMs) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | Skin Mf | Nodular Mf |

L3 | L3 Day1 |

L3 Day3 |

Adult Male |

Adult Female |

| OVOC8619 | Adhesion regulating molecule conserved region family protein |

119.1 | 141.9 | 26.8 | 116.9 | 124.5 | 99.3 | 41.0 |

| OVOC7083 | hypothetical protein Bm1_50435 | 27.4 | 257.9 | 72.9 | 29.6 | 94.8 | 63.1 | 67.6 |

| OVOC11598 | hypothetical protein LOAG_10445 | 2.2 | 66.7 | 58.8 | 9.7 | 9879.0 | 1.2 | 23.4 |

| OVOC10819 | hypothetical secreted protein precursor | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 153.3 | 1.0 |

| OVOC5395 | hypothetical protein Bm1_06245 | 23.9 | 101.9 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 38.7 | 13.1 | 14.7 |

| OVOC12235 | hypothetical protein LOAG_18989 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 336.4 | 31.7 | 235.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

Conclusion

The abundance of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data has provided novel biological insight into filarial nematodes, as well as allowed for the identification of novel drug targets and vaccine candidates. However, most of these analyses rely on annotated genes with orthologs in other species, such as C. elegans. The next challenge will be to assign functions to the many genes annotated as “uncharacterized” or “hypothetical proteins” in both the filarial and Wolbachia genomes through the development of high-throughput methods. It is only with the understanding of these hypotheticals that we will be able to go even further in exploring the novel biology of filarial parasites and their bacterial endosymbionts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hotez PJ, et al. The global burden of disease study 2010: interpretation and implications for the neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(7):e2865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash LR, Riley JM. Development of Brugia pahangi in the jird, Meriones unguiculatus, with notes on infections in other rodents. J Parasitol. 1970;56(5):962–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash LR. Chronic Brugia pahangi and Brugia malayi infections in Meriones unguiculatus. J Parasitol. 1973;59(3):442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.el-Bihari S, Ewert A. Worm burdens and prepatent periods in jirds (Meriones unguiculatus) infected with Brugia malayi. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1973;4(2):184–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saeung A, Choochote W. Development of a facile system for mass production of Brugia malayi in a small-space laboratory. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(9):3259–3265. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotton JA, et al. The genome of Onchocerca volvulus, agent of river blindness. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16216. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desjardins CA, et al. Genomics of Loa loa, a Wolbachia-free filarial parasite of humans. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng.2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau YL, et al. Draft genome of Brugia pahangi: high similarity between B. pahangi and B. malayi. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:451. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1064-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godel C, et al. The genome of the heartworm, Dirofilaria immitis, reveals drug and vaccine targets. FASEB J. 2012;26(11):4650–4661. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-205096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pombert JF, et al. A lack of parasitic reduction in the obligate parasitic green alga Helicosporidium. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(5):e1004355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghedin E, et al. Draft genome of the filarial nematode parasite Brugia malayi. Science. 2007;317(5845):1756–1760. doi: 10.1126/science.1145406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitreva M, et al. The draft genome of the parasitic nematode Trichinella spiralis. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):228–235. doi: 10.1038/ng.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghlan A. Nematode genome evolution. WormBook. 2005:1–15. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirai H, et al. Chromosomes of Onchocerca volvulus (Spirurida: Onchocercidae): a comparative study between Nigeria and Guatemala. J Helminthol. 1987;61(1):43–46. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x0000969x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Underwood AP, Bianco AE. Identification of a molecular marker for the Y chromosome of Brugia malayi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White MJD. Animal cytology and evolution. 3d. Cambridge, Eng.: University Press; 1973. viii, 961 p. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Post R. The chromosomes of the Filariae. Filaria J. 2005;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delves CJ, Howells RE, Post RJ. Gametogenesis and fertilization in Dirofilaria immitis (Nematoda: Filarioidea) Parasitology. 1986;92(Pt 1):181–197. doi: 10.1017/s003118200006354x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi Y, et al. Karyotypes of Brugia pahangi and Brugia malayi (Nematoda: Filarioidea) J Parasitol. 1983;69(6):1090–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller MJ. Observations on spermatogenesis in Onchocerca volvulus and Wuchereria bancrofti. Can J Zool. 1966;44(6):1003–1006. doi: 10.1139/z66-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Post RJ, et al. Chromosomes of six species of Onchocerca (Nematoda: Filarioidea) Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;40(3):292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Post RJ, Bain O, Klager S. Chromosome numbers in Onchocerca dukei and O. tarsicola. J Helminthol. 1991;65(3):208–210. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00010725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor MJ, Bandi C, Hoerauf A. Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts of filarial nematodes. Adv Parasitol. 2005;60:245–284. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster J, et al. The Wolbachia genome of Brugia malayi: endosymbiont evolution within a human pathogenic nematode. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(4):e121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darby AC, et al. Analysis of gene expression from the Wolbachia genome of a filarial nematode supports both metabolic and defensive roles within the symbiosis. Genome Res. 2012;22(12):2467–2477. doi: 10.1101/gr.138420.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNulty SN, et al. Endosymbiont DNA in endobacteria-free filarial nematodes indicates ancient horizontal genetic transfer. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ioannidis P, et al. Extensively duplicated and transcriptionally active recent lateral gene transfer from a bacterial Wolbachia endosymbiont to its host filarial nematode Brugia malayi. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luck AN, et al. Concurrent transcriptional profiling of Dirofilaria immitis and its Wolbachia endosymbiont throughout the nematode life cycle reveals coordinated gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1041. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luck AN, et al. Tissue-specific transcriptomics and proteomics of a filarial nematode and its Wolbachia endosymbiont. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:920. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingram JR, et al. Investigation of the proteolytic functions of an expanded cercarial elastase gene family in Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(4):e1589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingram J, et al. Proteomic analysis of human skin treated with larval schistosome peptidases reveals distinct invasion strategies among species of blood flukes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(9):e1337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horn M, et al. Trypsin- and Chymotrypsin-like serine proteases in schistosoma mansoni-- 'the undiscovered country'. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(3):e2766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doleckova K, et al. The functional expression and characterisation of a cysteine peptidase from the invasive stage of the neuropathogenic schistosome Trichobilharzia regenti. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennuru S, et al. Stage-Specific Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses of the Filarial Parasite Onchocerca volvulus and Its Wolbachia Endosymbiont. MBio. 2016;7(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.02028-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lustigman S, et al. RNA interference targeting cathepsin L and Z-like cysteine proteases of Onchocerca volvulus confirmed their essential function during L3 molting. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;138(2):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guiliano DB, et al. A gene family of cathepsin L-like proteases of filarial nematodes are associated with larval molting and cuticle and eggshell remodeling. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;136(2):227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song C, et al. Development of an in vivo RNAi protocol to investigate gene function in the filarial nematode, Brugia malayi. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(12):e1001239. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kariuki MM, Hearne LB, Beerntsen BT. Differential transcript expression between the microfilariae of the filarial nematodes, Brugia malayi and B. pahangi. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:225. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford L, et al. Characterization of a novel filarial serine protease inhibitor, Ov-SPI-1, from Onchocerca volvulus, with potential multifunctional roles during development of the parasite. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(49):40845–40856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maizels RM, et al. Immune evasion genes from filarial nematodes. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31(9):889–898. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Connell EM, et al. Targeting Filarial Abl-like Kinases: Orally Available, Food and Drug Administration-Approved Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Are Microfilaricidal and Macrofilaricidal. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(5):684–693. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feist AM, et al. Reconstruction of biochemical networks in microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(2):129–143. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song C, et al. Metabolic reconstruction identifies strain-specific regulation of virulence in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:708. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blazejewski T, et al. Systems-based analysis of the Sarcocystis neurona genome identifies pathways that contribute to a heteroxenous life cycle. MBio. 2015;6(1) doi: 10.1128/mBio.02445-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orth JD, Thiele I, Palsson BO. What is flux balance analysis? Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(3):245–248. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huthmacher C, et al. Antimalarial drug targets in Plasmodium falciparum predicted by stage-specific metabolic network analysis. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:120. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chavali AK, et al. Systems analysis of metabolism in the pathogenic trypanosomatid Leishmania major. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:177. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Driguez P, et al. Schistosomiasis vaccine discovery using immunomics. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaze S, et al. An immunomics approach to schistosome antigen discovery: antibody signatures of naturally resistant and chronically infected individuals from endemic areas. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(3):e1004033. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang YT, et al. Genome of the human hookworm Necator americanus. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):261–269. doi: 10.1038/ng.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Assis RR, et al. A next-generation proteome array for Schistosoma mansoni. Int J Parasitol. 2016;46(7):411–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinheiro CS, et al. Computational vaccinology: an important strategy to discover new potential S. mansoni vaccine candidates. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:503068. doi: 10.1155/2011/503068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makepeace BL, et al. The case for vaccine development in the strategy to eradicate river blindness (onchocerciasis) from Africa. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(9):1163–1165. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1059281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lustigman S, et al. Towards a recombinant antigen vaccine against Onchocerca volvulus. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(3):135–141. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)02211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caffrey CR. Drug discovery in infectious diseases. Weinheim, German: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. Parasitic helminths : targets, screens, drugs, and vaccines; p. 516. xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turaga PS, et al. Immunity to onchocerciasis: cells from putatively immune individuals produce enhanced levels of interleukin-5, gamma interferon, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in response to Onchocerca volvulus larval and male worm antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68(4):1905–1911. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1905-1911.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abraham D, et al. Immunoglobulin E and eosinophil-dependent protective immunity to larval Onchocerca volvulus in mice immunized with irradiated larvae. Infect Immun. 2004;72(2):810–817. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.810-817.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diemert DJ, et al. Generalized urticaria induced by the Na-ASP-2 hookworm vaccine: implications for the development of vaccines against helminths. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(1):169–176. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]