Abstract

Using asymmetric catalysis to simultaneously form carbon–carbon bonds and generate single isomer products is strategically important. Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling is widely used in the academic and industrial sectors to synthesize drugs, agrochemicals and biologically active and advanced materials. However, widely applicable enantioselective Suzuki-Miyaura variations to provide 3D molecules remain elusive. Here we report a rhodium-catalysed asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura reaction with important partners including aryls, vinyls, heteroaromatics and heterocycles. The method can be used to couple two heterocyclic species so the highly enantioenriched products have a wide array of cores. We show that pyridine boronic acids are unsuitable, but they can be halogen-modified at the 2-position to undergo reaction, and this halogen can then be removed or used to facilitate further reactions. The method is used to synthesize isoanabasine, preclamol, and niraparib—an anticancer agent in several clinical trials. We anticipate this method will be a useful tool in drug synthesis and discovery.

Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura procedures often have difficulty incorporating heterocyclic reagents, despite the importance of these in the pharmaceutical industry. Here the authors report a rhodium catalysed cross-coupling that tolerates a wide variety of nucleophiles including a range of heterocycles.

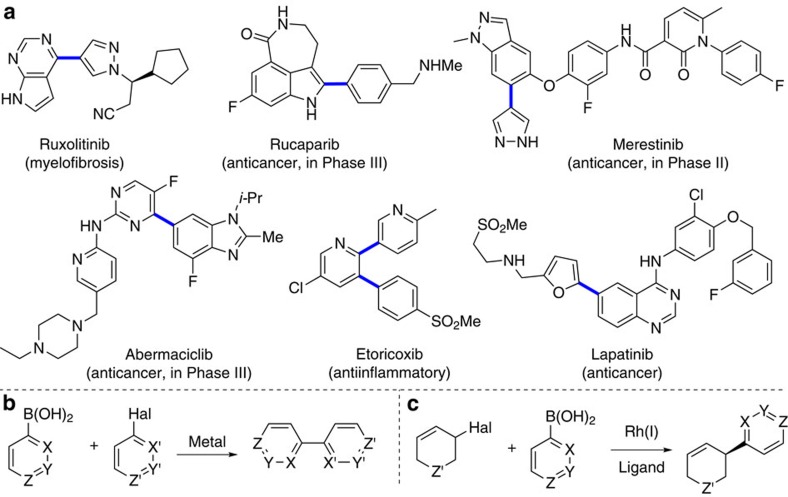

The ability to construct new bonds is important in chemical synthesis. A widely used approach is the metal catalysed cross-coupling of two simple molecules to create a more complex product1. In particular the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, which involves cross-coupling between an sp2-hybridized boronic acid and an sp2-hybridized halide, is robust and highly tolerant of varying the reaction partners. These features have made it arguably the most strategically important carbon–carbon bond forming reaction, and it is one of the top transformations used in drug discovery2. A key feature of Suzuki-Miyaura reactions is the ability to use heteroaromatic units as coupling partners. These are more difficult to work with than simple aromatics like benzene, but are essential components of many drugs and agrochemicals (Fig. 1a)3. It is now widely accepted that the exceptional reliability of Suzuki-Miyaura procedures to form Csp2–Csp2 bonds (Fig. 1b)4 has skewed drug development disproportionately toward materials which are essentially flat or planer and lack three-dimensionality—however, a major recent trend within drug discovery is to explicitly shift toward 3D molecules2,5.

Figure 1. Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling.

(a) Examples of drugs and late-stage drug candidates where Suzuki-Miyaura coupling is used to form key carbon–carbon bonds (shown in blue) with heterocyclic coupling partners. (b) The Suzuki-Miyaura reaction is strategically powerful in drug synthesis and design due to its robustness and tolerance of heterocycles. (c) This work: asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling to form Csp3–Csp2 bonds using heterocycles where X, Y or Z≠CH.

Efforts to extend Suzuki-Miyaura reactions to the preparation of enantiomerically pure compounds6 has led to a variety of enantiospecific methods using single-enantiomer alkylboron reagents7,8,9,10,11,12 or halide partners13. In terms of asymmetric methods, very few generally useful procedures have emerged, but desymmetrization strategies using meso-compounds are known14,15. Enantioselective Csp2–Csp2 coupling to form axially chiral biaryls is also well established16 and the Fu group pioneered stereoconvergent nickel-catalysed cross-coupling procedures between various nucleophiles and secondary coupling partners17,18. Despite this progress, relevant asymmetric procedures favour products with structural characteristics far from those typically seen in drugs and are generally restricted to aromatic or aliphatic partners. Methods that tolerate heterocycles have not been developed despite how heavily these feature in biologically active molecules3,5. As Suzuki-Miyaura coupling is the most widely used method for C–C bond forming heteroaryl elaboration19, the ability to use heterocycles is likely necessary for an asymmetric variations to become widely used20,21,22. Even in the absence of stereochemical questions, regio- and chemoselectivity issues with heteroaryls in sp2–sp2 coupling are of tremendous interest because of the inherent reactivity differences across heteroaromatics, and the possibility of performing multiple couplings on polyhalogenated heteroaromatics3,23.

Previous asymmetric reactions with sp2-hybridized boronic acid derivatives include 1,4- (ref. 24) and 1,2-additions25, allylic arylations26, allylic vinylations27, desymmetrizing allylic additions28,29, and allylic arylations to racemic substrates30. These work well with carbocyclic benzene derivatives, but the vast range of vinyl and heteroaromatic possibilities cannot generally be used20,27,31. Many vinylboronic acids cannot be used in asymmetric additions because they are unstable and readily undergo protodeboronation and polymerization32,33. We previously reported catalytic asymmetric addition of nucleophiles to racemic allylic halide starting materials34,35,36,37 including a system for boronic acid addition30 involving [Rh(cod)(OH)]2 and (S)-Xyl-P-PHOS in the presence of Cs2CO3. Although this system was suitable for an array of carbocyclic nucleophiles and a few electron rich styrenyl-boronic acids, it was not useful with other vinyl or heteroaromatic species.

Here we present a rhodium-catalysed asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling that allows variability in both coupling partners (Fig. 1c). A variety of aryl, vinyl and heteroaryl boronic acids react with carbo- and heterocyclic allyl halides. The method gives diverse pharmacologically important core structures bearing useful functional groups. The functional groups allow transformations including cross-coupling and addition reactions to rapidly elaborate the products. High enantioselectivity is observed, even when both coupling partners are heterocycles. We show that a class of cross-coupling partners (pyridine boronic acids) that do not undergo reaction can be coerced into cross-coupling by introducing a halogen to the core. If desired the halogen can be removed after asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura, or used in further cross-coupling reactions. The method is used to synthesize the pyridine-containing natural alkaloid isoanabasine, whose only previous asymmetric synthesis relied on separation of the racemic mixture of enantiomers38. This asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura reaction is also used in the key step of two syntheses of the antipsychotic drug preclamol, and in three syntheses of niraparib (ZEJULA), an anticancer agent in many late-stage clinical trials.

Results

Asymmetric reaction development

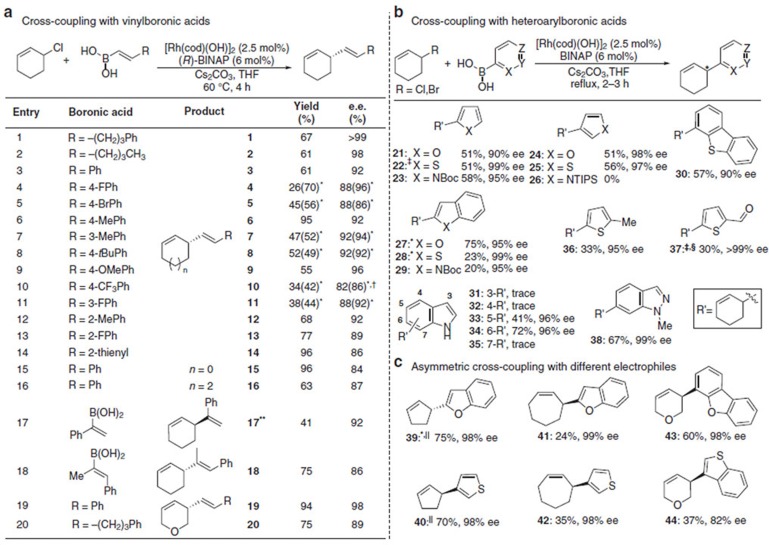

With the aim of developing a broadly useful asymmetric variant of Suzuki-Miyaura coupling with building blocks that go beyond simple bench-mark substrates, we extensively explored different catalytic systems by changing reaction parameters. Ultimately, we uncovered a variety of conditions that provide comparable (Supplementary Fig. 1) and complementary (shown below) results. We first sought useful conditions for vinylboronic acid coupling, and after thoroughly screening parameters found that BINAP generally gave better results which allowed us to use a variety of styrene derivatives with high yields and enantioselectivities (Fig. 2a, entries 1–13), although in some cases Xyl-P-PHOS was a more effective ligand (entries 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 11). We found that when using 1-phenyl-1-vinylboronic acid, the major product formed was the regioisomer 3 in 75% yield and 91% ee. However, when the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 48 h, the major isomer was 17 in a 4.5:1 ratio. 17 was isolated in 41% yield and 92% ee. The method is suitable for trisubstituted boronic acids as well as additions to 5-,7- and oxygen-containing rings (15, 16, 19 and 20).

Figure 2. Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling using vinyl- and heteroaryl boronic acids.

(a) Cross-coupling vinylboronic acids to cyclic allyl chlorides. Conditions: 0.4 mmol of allyl chloride, 0.8 mmol of vinylboronic acid, [Rh(cod)(OH)]2 (2.5 mol%), ligand (6 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.0 eq) in THF at 60 °C. (b) Testing various heteroaromatic boronic acids in asymmetric cross-coupling. (c) Hetereoaryl boronic acids used in combination with different allyl chlorides. Conditions: 0.4 mmol of allyl chloride, 1.2 mmol of heteroaryl boronic acid, [Rh(cod)(OH)]2 (2.5 mol%), ligand (6 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.00 eq) in THF at reflux. *In these experiments Xyl-P-PHOS was used instead of BINAP. †It is difficult to determine the ee of product 10 and the ee values here have an estimated error of ±10%. ‡Allyl bromide was used instead of allyl chloride. §The reaction was performed at r.t. for 16 h. ‖In these experiments 5 mol% [Rh(cod)(OH)]2 and 12 mol% ligand was used and the reaction stirred for four hours at reflux while protected from light. All yields are isolated yields. Enantiomeric excesses determined by HPLC, GC or SFC using a chiral non-racemic stationary phase. **Reaction using (S)-BINAP and stirred at room temperature 48 h.

Although thousands of heteroaryl boronic acids are known, for practical reasons we examined a representative unsubstituted set to judge whether these are suitable for asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling. BINAP was used, >2 equiv. of boronic acid and heating to reflux gave good results (Fig. 2b). At the 2-position of 5-membered O, S and N (Boc-protected) heterocycles, asymmetric addition was observed in >50% yield and very high ee (90–99%, 21–23). At the 3-position, furan 24 (98% ee) and thiophene 25 (97% ee) derivatives also worked well, but products from a protected 3-pyrrole 26 were never isolated, likely due to rapid base-mediated protodeboronation39. 2-Boronic acid substituted 5-membered heterocycles fused to a benzene ring gave excellent levels of ee (all >95%) with high yield in the case of benzofuran (27, 75%) but low yields with benzothiophene 28 (23%) and protected indole 29 (20%). Dibenzothiophene (to give 30, 57% 90% ee) and dibenzofuran could be added successfully, but the product from the furan derivative could not be satisfactorily separated from protoboronated dibenzofuran. For indole addition, reaction at the 5- and 6-position gave good results with excellent ee’s (33 and 34, both 96% ee) in sharp contrast 3-, 4- and 7-isomers, which could only be obtained in very small amounts due to the stability of the boronic acids during synthesis or under the reaction conditions. Because they were readily available we also examined 5-substituted thiophenes, which produced 36 and 37 with very high enantioselectivities (95–99% ee) and indazolyl to give 38 in 67% yield with 99% ee. A variety of different electrophiles were also successfully employed using heterocyclic boronic acids (Fig. 2c).

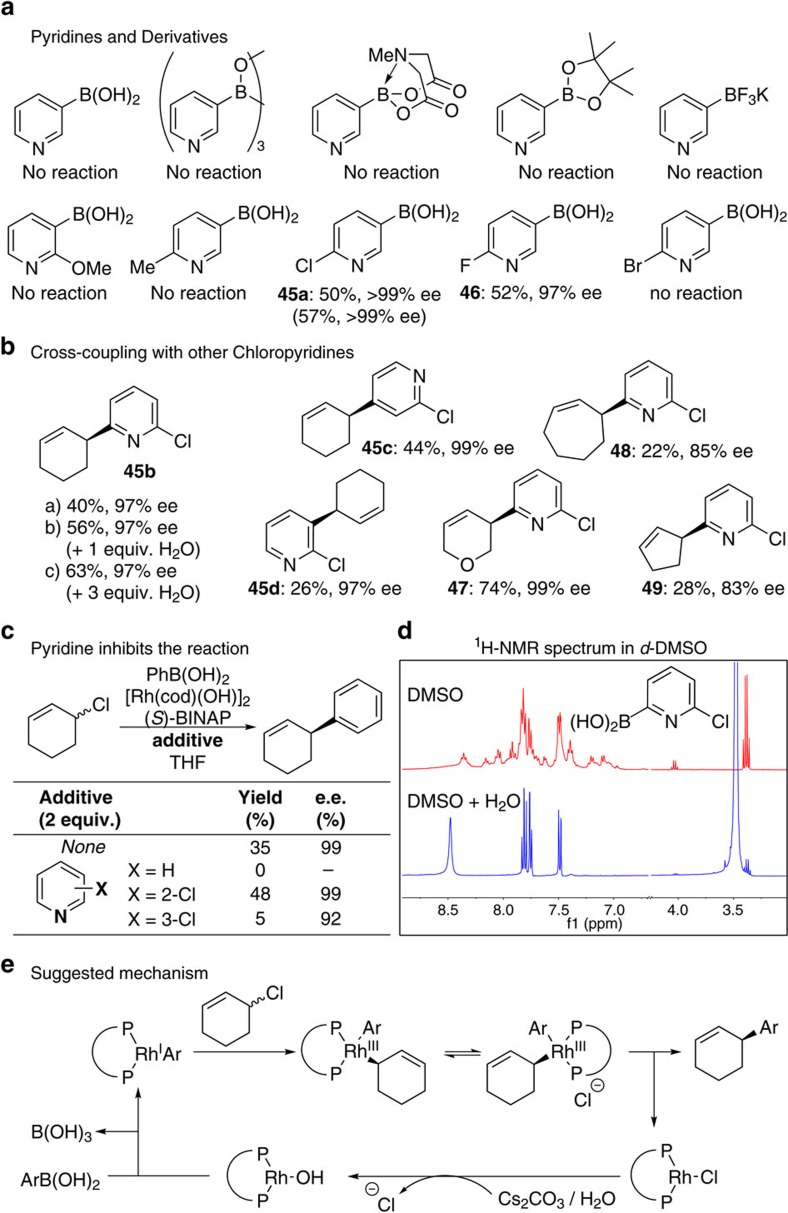

Coupling with pyridylboronic acid derivatives

The most valuable heterocycles are arguably pyridine derivatives, which are important in catalysis, drug design, molecular recognition and feature in many natural products. Experiments with pyridine boronic acids were unsuccessful, as were extensive experiments using boronic acid derivatives under various conditions (Fig. 3a). We decided to modulate the pyridine electronics by introducing various substituents and found that 2-chloro and 2-fluoro pyridines could be used with respectable (>50%) yield and excellent (>97% ee) enantioselectivity. Upon examining all regioisomers of 2-chloropyridine boronic acids we observe uniformly high enantioselectivity (97–99% ee, 45a–45d) when coupling to 6-membered rings although the yield with 2-chloro-3-boronic acid-pyridine 45d was low (26%) and couplings to 5- and 7-membered rings gave poor ee’s (80–85% ee). These results show that coupling success is highly dependent on the heterocycle, and in unsuccessful cases heterocycle modifications can be made to make the asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura viable. Later we show that the 2-Cl-group can be readily removed or become part of synthesis design to allow subsequent transformations.

Figure 3. Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling with pyridine-derived boronic acids.

(a) Examination of pyridine boronic acid derivatives and core-modified pyridyl boronic acids. (b) Cross-coupling of various chloropyridineboronic acids. (c) Pyridine inhibits an asymmetric coupling reaction while 2-Cl-pyridine does not, suggesting that the role of the 2-Cl-unit is to make the pyridine-based partner less Lewis basic and bind less effectively to Rh-species. (d) Addition of water to the 2-Cl-pyridinyl boronic acid simplifies its NMR spectra in DMSO suggesting it breaks aggregates into monomers. (e) Tentative reaction mechanism for the Rh-catalyzed cross-coupling. All yields are isolated yields.

In an attempt to understand the pyridine-based boronic acid behaviour we performed asymmetric coupling of phenylboronic acid and cyclohexenyl chloride using heteroaryl-optimized conditions in the presence of additives (Fig. 3c)40. With no additive the reaction provided the carbocyclic coupling product (35%, 99% ee), but if pyridine is added the reaction does not work. Conversely, in the presence of 2 equivalents of 2-Cl-pyridine the coupling proceeds similarly to the unspiked reaction (48% yield, 99% ee). With 3-Cl-pyridine, only a very small amount of product is obtained with lower (92%) ee. Although we suspect the poor results with 3-pyrrole and indole boronic acids (Fig. 2) are due to competitive protodeboronation39, in the case of pyridines it is likely that the N-lone pairs interfere by binding to rhodium and shutting down a key step in the mechanistic cycle. The role of the 2-F or 2-Cl substituent would be to remove electron density, and hence Lewis basicity, from the pyridine ring. And the observed trend is consistent with their measured and calculated pKa values (pyr ∼5.2, 3-Cl-pyr ∼2.8 and 2-Cl-pyr ∼0.7)41.

During studies on 45b we established that the addition of water considerably impacts performance, and we demonstrate that in the presence of three equivalents of water the yield improves from 40 to 63% over dry conditions (Fig. 3b). The water may break up boron-aggregates into acid monomers as suggested by NMR spectroscopy experiments where water is added to 45b in DMSO (Fig. 3c) and/or facilitate regeneration of L*RhOH species for the catalytic cycle (Fig. 3e). A plausible reaction mechanism, which we believe is consistent with our experiments, is proposed. Key steps involve transmetallation of boronic acids from B to Rh, which is likely to involve L*RhOH, and oxidative addition of (hetero)aryl-Rh species with the allyl chloride. The resulting Rh(III) intermediate may undergo suprafacial 1,3-isomerization between two different allyl species, and if reductive elimination is rate-determining this would provide a mechanism for enantioselection. These proposed steps are all tentative and elucidation of the actual mechanism will require careful further study.

Use of piperidine substrates

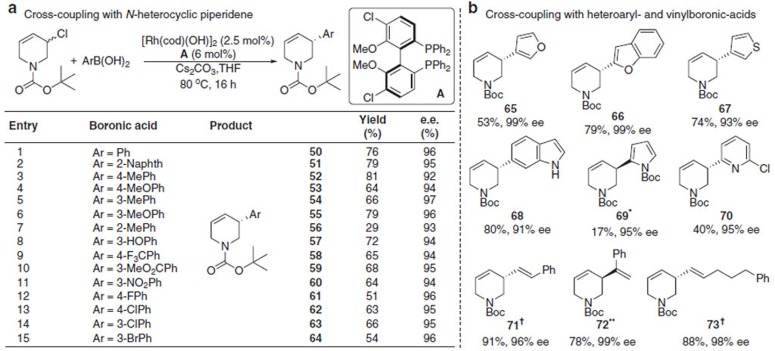

Using an N-heterocyclic allyl chloride partner, which gives products of great interest to synthesis and biology, tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) was found to be a suitable and easily removable N-protecting group. Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling to provide dehydropiperidine products are scarce, with the most relevant method being enantiospecific coupling of enantiomerically enriched allylic boronates42. With phenylboronic acid the conditions above gave lower ee’s (Supplementary Fig. 52), but we found that Cl-OMe-BIPHEP A gave excellent results (76%, 96% ee, Fig. 4a, entry 1). Modified conditions are required but they simply involve heating the reaction mixture in a septum-sealed round-bottomed flask to 80 °C under an inert atmosphere. For reasons that are unclear the use of a reflux condenser reproducibly gives inferior results. Alternatively we found the reaction can be accomplished by heating in a sealed microwave-vial overnight, or in <1 h using microwave heating set at 80 °C. A variety of substituted arylboronic acids could be coupled in this manner with uniformly high ee’s (92–97% ee), and good yields (>50%), except in the case of ortho-substitution (entry 7) which, likely for steric reasons, gave 56 in 29% yield.

Figure 4. Coupling piperidenyl derivatives.

(a) Addition of arylboronic acids to N-Boc-3-chloro-4-piperidene. Conditions: piperidinyl chloride (1.0 equiv.), boronic acid (2.0 equiv.), [Rh(cod)(OH)]2 (2.5 mol%), A (6 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.0 equiv.) in THF at 80 °C with stirring for 16 h. Enantiomeric excess determined by HPLC using a chiral non-racemic stationary phase. (b) Addition of heteroaromatic- and vinylboronic acids to N-Boc-3-chloro-4-piperidene. *(S)-BINAP was used instead of (R)-A. †(R)-BINAP was used instead of (R)-A. All yields are isolated yields. **Reaction using (S)-A run and stirred at room temperature 72 h.

Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of two heterocycles

We next examined the challenging scenario where both coupling partners are heterocycles (Fig. 4b). 3-Furan, 2-benzofuran, 3-thiophene and 6-indole boronic acids performed well with the N-heterocycle under these conditions. Boc-protected 2-pyrrole boronic acid gave 69 in low yield, again likely due to sterics, but excellent (95%) ee. Modified-pyridine and vinylboronic acids also couple to the piperidene to rapidly give complex products with very high (93–99%) ee. As we observed in the earlier example, the addition of 1-phenyl-1-vinylboronic acid at 60 °C yields 71 as the major regioisomer. If the reaction is performed at room temperature and stirred 72 h, then 72 is the major product in a 7:1 ratio. 72 was obtained in 78% yield and 99% ee.

Synthetic potential and applications

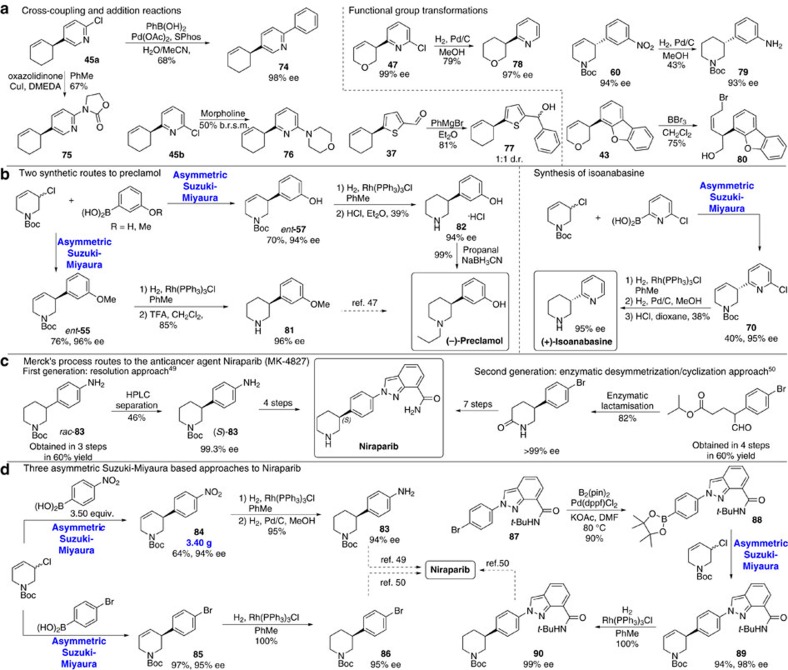

After establishing that diverse coupling partners can be used in asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling we explored if the products could be used in further transformations (Fig. 5a). The 2-Cl-pyr-unit, necessary for successful reaction with pyridines, allows Pd-catalysed Suzuki-Miyaura to give 74 and Cu-catalysed Buchwald-Hartwig coupling to give 75. Similarly, 45b can be converted to 76 via SNAr addition. As shown above (Fig. 2, 37) sensitive aldehyde groups tolerate asymmetric coupling, providing a convenient handle for elaboration and we demonstrate addition of the prototypical nucleophile PhMgBr (37–77). We demonstrate that the 2-Cl-unit can be readily dechlorinated; here, hydrogenation of the double bond also occurs using H2 and Pd/C. Double nitro- and olefin-group reduction (60–79) can be accomplished using the same conditions. In these Pd-catalysed hydrogenations little racemization occurs, but in some later experiments hydrogenations were performed using Wilkinson’s catalyst to avoid racemization. Furthermore, the allyl units generated in the reaction can mask highly functionalized building blocks for synthesis, and we show how regiospecific BBr3-mediated ring opening (43–80) generates an enantiomerically pure heterocycle bearing both a cis-allyl bromide and an alcohol.

Figure 5. Further transformation of asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura products and applications in drug and natural product synthesis.

(a) Representative transformations of different asymmetric coupling products: cross-coupling and SNAr reactions with 2-pyridine derivatives, nucleophile addition to an aldehyde, dehalogenation/hydrogenation, chemoselective ring opening with BBr3 and nitro-group reduction/hydrogentation. (b) Application of the method to the synthesis of the drug (−)-preclamol and the natural product (+)-isoanabasine. (c) Syntheses of the anticancer agent niraparib by Merck. Merck’s first process route involved resolution of racemic starting material by HPLC. Their second-generation route used an enzymatic lactamization approach to provide enantiomerically pure material. (d) To highlight the robustness and flexibility of asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling we used it as the key step in three different approaches to niraparib. All three syntheses intercept an intermediate reported by Merck and show high overall yields and levels of enantioselectivity. All yields are isolated yields.

Many chiral drugs administered in enantiopure form are prepared as racemic mixtures and resolved via classical or chromatographic processes43 and the ability to use an asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling during molecular construction would be a highly attractive alternative. To demonstrate the method can be used to synthesize valuable molecules we prepared the antipsychotic drug preclamol44 whose asymmetric synthesis has recently been reported using powerful methods45,46. Using standard conditions for piperidene derivatives, 81 which had been previously converted to preclamol47, was prepared from 3-MeO-Ph boronic acid in three steps in 64% overall yield and 96% ee (Fig. 5b). Alternatively, unprotected 3-phenol boronic acid afforded ent-57 (70%, 94% ee) and gives preclamol via a novel route involving hydrogenation and deprotection (39% yield) followed by reductive amination (99% yield).

We demonstrate that the asymmetric cross-coupling of two heterocyclic species can be used to synthesize the natural product isoanabasine, which bears considerable resemblance to common central nervous system activators. The only previous asymmetric synthesis of isoanabasine relied on preparation of the racemate followed by resolution using stoichiometric BINOL38. Here we used 2-Cl-pyridine boronic acid to obtain 70 in 40% yield and 95% ee. Isoanabasine was obtained after sequential hydrogenation using Wilkinson’s catalyst to reduce the double bond and then Pd/C to dehalogenate the pyridinyl moiety, followed by Boc deprotection (38% yield over three steps).

Niraparib (MK-4827) is a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor with potential antineoplastic activity that is currently in at least 8 different clinical trials for various cancers including those of the breast, ovarian, lung and prostate48. The medicinal chemistry approach to niraparib involved the tartaric acid salt of a 3-aryl piperidine and inefficient resolution via multiple crystallizations (20% yield, 80–90% ee), followed by chiral HPLC purification at a later stage49. For the large scale synthesis Merck first developed an approach based on chiral HPLC separation of rac-83 (46% yield, 94% ee) capable of 0.27 Kg separated product per Kg stationary phase per day (Fig. 5c)49. A second-generation route involves a novel transaminase-mediated dynamic kinetic resolution which overcame limitations of the previous approach and demonstrates the enabling potential of advances in catalysis technology on chemical process development50.

We demonstrate the power of our approach by describing three different catalytic asymmetric syntheses of niraparib (Fig. 5d). First we intercepted intermediate 83 from Merck’s resolution route by coupling piperidene chloride with 4-nitrobenzeneboronic acid to give 84 (64% yield, 94% ee). To test the robustness of the method we performed a larger-scale reaction to give 3.4 grams of product. Two-stage reduction, first using Wilkinson’s catalyst to hydrogenate the double bond, then Pd/C catalysed nitro-reduction, gave 83 in 95% yield (94% ee). Alternatively, asymmetric coupling using 4-bromobenzene boronic acid provides heterocycle 85 (97%, 95% ee) which can easily be hydrogenated to Boc-protected piperidine 86 (100% yield) a key intermediate in Merck’s second generation synthesis. Finally, we envisaged that the synthesis could be made more convergent by using a complex boronic acid in the asymmetric coupling. We prepared boronate ester 88 as the corresponding boronic acid was poorly behaved making it difficult to isolate and unsuitable for asymmetric coupling. However, use of boronate ester 88 directly afforded 89 (94% yield, 98% ee) and quantitative reduction gave piperidene 90. Previously, 90 was prepared in nine steps and then doubly deprotected to niraparib.

It is anticipated that the ability to couple boronic acids with allylic halides in an asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura reaction, particularly when two heterocyclic partners are coupled, will become a widely used transformation in drug discovery and synthesis. In pyridine derivatives, halogen-modification allows coupling to occur, suggesting that many additional heterocycles will be compatible with this approach as it develops. The halogen modifications also facilitate subsequent transformations and enable efficient synthesis design as well as strategies for producing libraries of compounds for screening. The short syntheses of preclamol, isoanabasine and niraparib highlight the flexibility and utility of the method.

Methods

General Methods

For synthetic details and analytical data for all reaction products see Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its accompanying Supplementary Information file, which are both free of charge to access. For NMR spectra and HPLC, GC or UPLC traces see Supplementary Figs 2–51 and 53–99.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Schäfer, P. et al. Asymmetric Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of heterocycles via Rhodium-catalysed allylic arylation of racemates. Nat. Commun. 8, 15762 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15762 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures, supplementary methods and supplementary references.

Acknowledgments

P.S. and T.P. thank the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under REA grant agreement 316955 for funding. Financial support from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/N022246/1) is gratefully acknowledged.

Oxford University Innovation has filed a patent application (PCT/GB2016/051612) with S.P.F. and M.S. named as inventors. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions P.S., T.P. and M.S. performed experiments. P.S., T.P., M.S. and S.P.F. designed experiments, analysed experimental results and wrote the paper.

05/25/2018

The authors became aware of an error in the original version of this Article in that two products, 17 and 72, were incorrectly assigned as the 1,1-alkenylated products, but the products obtained in these experiments were in fact 1,2-alkenylated isomers. The 1,1-disubstituted isomers 17 and 72 can be obtained as the major products if the Suzuki-Miyaura reactions are run at room temperature. As a result of this, a number of changes have been made to the original version of this Article. A full list of these changes is available online.

References

- Armin, D. M., Stefan, B. & Martin, O. (eds). Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions and More Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G. & Boström J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? J. Med. Chem. 59, 4443–4458 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond-Thynne J., Blakemore D. C., Pryde D. C. & Spivey A. C. Site-selective Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of heteroaryl halides—understanding the trends for pharmaceutically important classes. Chem. Sci. 8, 40–62 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaura N. & Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem. Rev. 95, 2457–2483 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Lovering F., Bikker J. & Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752–6756 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherney A. H., Kadunce N. T. & Reisman S. E. Enantioselective and enantiospecific transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organometallic reagents to construct C–C bonds. Chem. Rev. 115, 9587–9652 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S. M., Deng M. Z., Xia L. J. & Tang M. H. Efficient Suzuki-type cross-coupling of enantiomerically pure cyclopropylboronic acids. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 37, 2845–2847 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmura T., Awano T. & Suginome M. Stereospecific Suzuki−Miyaura coupling of chiral α-(acylamino)benzylboronic esters with inversion of configuration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 13191–13193 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imao D., Glasspoole B. W., Laberge V. S. & Crudden C. M. Cross coupling reactions of chiral secondary organoboronic esters with retention of configuration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5024–5025 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C. H., McDonald R. & Hall D. G. Enantioselective preparation and chemoselective cross-coupling of 1,1-diboron compounds. Nat. Chem. 3, 894–899 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molander G. A. & Wisniewski S. R. Stereospecific cross-coupling of secondary organotrifluoroborates: potassium 1-(benzyloxy)alkyltrifluoroborates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16856–16868 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet A., Odachowski M., Leonori D., Essafi S. & Aggarwal V. K. Enantiospecific sp2–sp3 coupling of secondary and tertiary boronic esters. Nat. Chem. 6, 584–589 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He A. & Falck J. R. Stereospecific Suzuki cross-coupling of alkyl α-cyanohydrin triflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2524–2525 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis M. C., Powell L. H. W., Claverie C. K. & Watson S. J. Enantioselective Suzuki reactions: catalytic asymmetric synthesis of compounds containing quaternary carbon centers. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 43, 1249–1251 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Potter B. & Morken J. P. A catalytic enantiotopic-group-selective Suzuki reaction for the construction of chiral organoboronates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6534–6537 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J. & Buchwald S. L. A catalytic asymmetric Suzuki coupling for the synthesis of axially chiral biaryl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 12051–12052 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Saito B. & Fu G. C. Enantioselective alkyl−alkyl Suzuki cross-couplings of unactivated homobenzylic halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6694–6695 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin P. M. & Fu G. C. Asymmetric suzuki cross-couplings of activated secondary alkyl electrophiles: arylations of racemic α-chloroamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11027–11029 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley S. D. & Jordan A. M. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 54, 3451–3479 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G. P. Asymmetric and diastereoselective conjugate addition reactions: C–C bond formation at large scale. Org. Process Res. Dev. 16, 1258–1272 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. W. J., Campbell I. B. & MacDonald S. J. F. Factors determining the selection of organic reactions by medicinal chemists and the use of these reactions in arrays (Small Focused Libraries). Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 49, 8082–8091 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadin A., Hattotuwagama C. & Churcher I. Lead-oriented synthesis: a new opportunity for synthetic chemistry. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 51, 1114–1122 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Bellina F. & Lessi M. Selective palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura reactions of polyhalogenated heteroarenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 354, 1181–1255 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M. & Kulawiec R. J. Mechanism of the ruthenium-catalyzed reconstitutive condensation of allylic alcohols and terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 5579–5584 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama M., Soeta T., Hao X., Chen Q. & Tomioka K. N -Boc- l -valine-connected amidomonophosphane rhodium(i) catalyst for asymmetric arylation of N- tosylarylimines with arylboroxines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 8128–8129 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiuchi H., Takahashi D., Funaki K., Sato T. & Oi S. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric coupling reaction of allylic ethers with arylboronic acids. Org. Lett. 14, 4502–4505 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. Y., Sarlah D. & Carreira E. M. Iridium-catalyzed enantioselective allylic vinylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 994–997 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T., Takahashi Y. & Murakami M. Rhodium-catalysed substitutive arylation of cis-allylic diols with arylboroxines. Chem. Commun. 595–597 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., Menard F., Isono N. & Lautens M. Synthesis of homoallylic alcohols via Lewis acid assisted enantioselective desymmetrization. Synthesis 2009, 853–859 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Sidera M. & Fletcher S. P. Rhodium-catalysed asymmetric allylic arylation of racemic halides with arylboronic acids. Nat. Chem. 7, 935–939 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht F., Sowada O., Fistikci M. & Boysen M. M. K. Heteroarylboronates in rhodium-catalyzed 1,4-addition to enones. Org. Lett. 16, 5212–5215 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duursma A. et al. Highly enantioselective conjugate additions of potassium organotrifluoroborates to enones by use of monodentate phosphoramidite ligands. J. Org. Chem. 69, 8045–8052 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T. & Berthon G. Catalytic Asymmetric Conjugate Reactions Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA (2010). [Google Scholar]

- You H., Rideau E., Sidera M. & Fletcher S. P. Non-stabilized nucleophiles in Cu-catalysed dynamic kinetic asymmetric allylic alkylation. Nature 517, 351–355 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidera M. & Fletcher S. P. Cu-catalyzed asymmetric addition of sp2 -hybridized zirconium nucleophiles to racemic allyl bromides. Chem. Commun. 51, 5044–5047 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideau E. & Fletcher S. P. Copper-catalysed asymmetric allylic alkylation of alkylzirconocenes to racemic 3,6-dihydro-2 H -pyrans. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 11, 2435–2443 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideau E., You H., Sidera M., Claridge T. D. W. & Fletcher S. P. Mechanistic studies on a Cu-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation with cyclic racemic starting materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5614–5624 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C.-Q., Cheng Y.-Q., Guo H.-Q., Qiu X.-P. & Gao L.-X. The natural alkaloid isoanabasine: synthesis from 2,3′-bipyridine, efficient resolution with BINOL, and assignment of absolute configuration by Mosher’s method. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 16, 2141–2147 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Cox P. A., Leach A. G., Campbell A. D. & Lloyd-Jones G. C. Protodeboronation of heteroaromatic, vinyl, and cyclopropyl boronic acids: pH–rate profiles, autocatalysis, and disproportionation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9145–9157 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K. D. & Glorius F. Intermolecular reaction screening as a tool for reaction evaluation. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 619–627 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero N. A., Melendez F. J., Muñoz-Caro C. & Niño A. Theoretical prediction of relative and absolute pKa values of aminopyridines. Biophys. Chem. 124, 155–160 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Rybak T. & Hall D. G. Synthesis of chiral heterocycles by ligand-controlled regiodivergent and enantiospecific Suzuki Miyaura cross-coupling. Nat. Commun. 5, 5474 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson S. & Allenmark S. G. Preparative chiral chromatographic resolution of enantiomers in drug discovery. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 54, 11–23 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchia M. et al. New N – n -propyl-substituted 3-aryl- and 3-cyclohexylpiperidines as partial agonists at the D 4 dopamine receptor. J. Med. Chem. 46, 161–168 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J. Y., Sarlah D. & Carreira E. M. Iridium-catalyzed enantioselective allylic alkylation with functionalized organozinc bromides. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 54, 7644–7647 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia T. et al. A Cu/Pd cooperative catalysis for enantioselective allylboration of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13760–13763 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom H. et al. Resolved 3-(3-hydroxypheny1)-N-n -propylpiperidine and its analogues: central dopamine receptor activity. J. Med. Chem. 27, 1030–1036 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Trials of Niraparib. Available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=niraparib&Search=Search (accessed May 9, 2017).

- Wallace D. J. et al. Development of a fit-for-purpose large-scale synthesis of an oral PARP inhibitor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 15, 831–840 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chung C. K. et al. Process development of C–N cross-coupling and enantioselective biocatalytic reactions for the asymmetric synthesis of niraparib. Org. Process Res. Dev. 18, 215–227 (2014). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures, supplementary methods and supplementary references.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its accompanying Supplementary Information file, which are both free of charge to access. For NMR spectra and HPLC, GC or UPLC traces see Supplementary Figs 2–51 and 53–99.