Abstract

Tumor suppressor p53 slides along DNA and finds its target sequence in drastically different and changing cellular conditions. To elucidate how p53 maintains efficient target search at different concentrations of divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+, we prepared two mutants of p53, each possessing one of its two DNA-binding domains, the CoreTet mutant having the structured core domain plus the tetramerization (Tet) domain, and the TetCT mutant having Tet plus the disordered C-terminal domain. We investigated their equilibrium and kinetic dissociation from DNA and search dynamics along DNA at various [Mg2+]. Although binding of CoreTet to DNA becomes markedly weaker at higher [Mg2+], binding of TetCT depends slightly on [Mg2+]. Single-molecule fluorescence measurements revealed that the one-dimensional diffusion of CoreTet along DNA consists of fast and slow search modes, the ratio of which depends strongly on [Mg2+]. In contrast, diffusion of TetCT consisted of only the fast mode. The disordered C-terminal domain can associate with DNA irrespective of [Mg2+], and can maintain an equilibrium balance of the two search modes and the p53 search distance. These results suggest that p53 modulates the quaternary structure of the complex between p53 and DNA under different [Mg2+] and that it maintains the target search along DNA.

Introduction

Transcriptional factor p53 is an important DNA-binding protein that controls the fate of cells and suppresses their canceration. Once p53 is activated by various stresses to cells, it searches for and binds to target DNA sequences. This binding regulates the expression of downstream proteins, resulting in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or DNA repair (1, 2). The functional form of p53 is a homotetramer of 393-residue monomers, each of which comprises a disordered N-terminal domain (residues 1–95), structured core domain (residues 95–293), disordered linker (residues 293–326), structured tetramerization (Tet) domain (residues 326–357), and disordered C-terminal (CT) domain (residues 357–393) (Fig. 1) (3, 4, 5). Many mutations of p53, which are mostly located in the core domain and hinder the binding of p53 to target DNA, are known to cause cancers, corresponding to ∼50% of the gene mutations found in human cancers (5). The mechanism underlying p53 searching for the target sequence has been the subject of extensive investigations (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). This study specifically examined the molecular mechanism for maintenance of p53 search efficiency in drastically different cellular conditions.

Figure 1.

Primary structures of FL-p53, CoreTet, and TetCT. Brown, green, black, yellow, and red denote the N-terminal domain, core domain, linker, tetramerization (Tet) domain, and C-terminal (CT) domain, respectively. Domains drawn by thick and thin lines possess folded and disordered conformations, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

To find the target site in a genome efficiently and accurately, activated p53, formed by various posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, performs facilitated diffusion (13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21) in which it combines one-dimensional (1D) and three-dimensional (3D) searches. In the 1D search, p53 first binds to and moves along the nonspecific sequence of DNA searching for the target sequence. The movement of p53 along DNA is diffusive, as characterized by single-molecule fluorescence microscopy (6, 7, 10, 11). The 1D search of p53 is independent of [K+], indicating that p53 performs sliding, defined as the diffusive movement of a protein along DNA maintaining a continuous electrostatic contact with DNA (7). By contrast, the diffusion of a mutant of p53 containing only the tetrameric form of the core domain depends on [K+], suggesting hopping, which is defined as the diffusive movement of a protein based on the repetition of short-term dissociation from and association to DNA (7). The inactivated p53 possesses a low target-recognition probability, implying that the sliding p53 frequently passes over the target (22). In contrast, p53 activation increases the target-recognition probability and promotes target binding in the 1D search (22). In the 3D search, p53 dissociates from and rebinds to DNA, leading to relatively long jumps of the scanning region in the 1D search. The frequency of the 3D search can be examined by the kinetic association and dissociation constants of p53 to nontarget DNA (11, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31). Accordingly, the efficiency and accuracy in the target search of p53 as well as of other DNA-binding proteins is achieved based on the interplay of distinct elementary processes that can be examined by various approaches (32, 33, 34, 35).

A recent discovery demonstrated that the efficiency of the facilitated diffusion of p53 is maintained under varying conditions of cells (11). An important parameter that determines the efficiency of the facilitated diffusion is the search distance, which is the average search distance of p53 along DNA upon one binding event and is inversely proportional to the search time for the target site (36, 37, 38). We demonstrated that the search distance does not change significantly at different concentrations of divalent cations such as Mg2+ and Ca2+. The concentration of divalent cations in cells is known to change dramatically and quickly depending on the cellular conditions. For example, the total [Mg2+] in cells is 5–30 mM; the free [Mg2+] is 0.4–0.6 mM (39). The Mg2+ deficiency induces cell cycle arrest (40). The Ca2+ concentration, which ranges from 100 nM to 1.7 μM (41), increases during the early phase of apoptosis (42, 43). Because divalent cations interact strongly with nucleotides (44, 45, 46, 47, 48), they might weaken the interaction between p53 and DNA. Our results showed that the 1D diffusion coefficient of p53 along DNA is strongly accelerated by increasing [Mg2+] and [Ca2+] from submillimolar to millimolar concentrations (11). In addition, the average residence time of p53 after binding to DNA is decreased by the addition of the divalent cations (11). The changes in the 1D diffusion coefficient and the residence time compensate each other and make the search distance nearly constant with changes in the divalent cations (11). The maintenance of the target search efficiency of p53 under changing concentrations of divalent cations is expected to be an integrated function of p53 that is necessary for cell canceration suppression.

The unique p53 domain arrangement suggests that intricate modulation of its target search dynamics, including the response to the divalent cations, is achieved through coordinated dynamics of each domain. Tafvizi et al. (7) constructed p53 mutants in which one of the two DNA-binding domains was deleted, and they examined the 1D search dynamics of the mutants. The 1D search of the mutant without the CT domain was much slower than that of the full-length p53 (FL-p53) and the mutant without the core domain, suggesting that the CT domain has a role in accelerating the 1D search of FL-p53. Our earlier study also revealed that the 1D search of FL-p53 is heterogeneous, comprising two modes with fast and slow diffusion coefficients, termed the “fast” and “slow” modes, respectively (11). The different search modes of p53 are likely to be the result of the different domain arrangement in the complex between p53 and DNA, because a mutant of p53 without the core domain does not possess the slow mode (11). The diffusion coefficient for the slow mode does not change over different [Mg2+], whereas the diffusion coefficient of the fast mode alone changes sigmoidally against [Mg2+] (11). In this article, we will differentiate the fast mode at the low and high [Mg2+] assuming different structures of p53-DNA complex, and name the former and latter the fast-I and fast-II modes, respectively. Accordingly, the different domains of p53 play different roles in the search dynamics to the target sequence. Nevertheless, how the domains maintain the constant search distance of FL-p53 at different concentrations of the divalent cations remains unclear.

To elucidate the roles of each domain in the 1D-search dynamics of p53 at different [Mg2+], we used the strategy used by Tafvizi et al. (7) and examined the two mutants of p53, in which one of the two DNA-binding domains was deleted. We investigated the equilibrium dissociation constant and the kinetic dissociation constant from the nonspecific sequence of DNA for the CoreTet mutant having the core domain plus the Tet domain, and TetCT mutant having the Tet domain plus the CT domain. Additionally, we measured the 1D diffusion of each mutant along a nonspecific DNA sequence by single-molecule fluorescence microscopy. We revealed that CoreTet diffuses along DNA and possess the fast-I and slow modes, the ratio of which depends strongly on [Mg2+]. In contrast, TetCT possessed only the fast-II mode, whose diffusion coefficient depends slightly on [Mg2+]. On the basis of comparison of the obtained parameters for FL-p53 and those for each mutant, we proposed a three-state model of the p53-DNA complex, based on the slow, fast-I, and fast-II modes. Furthermore, we found that the disordered CT domain of p53 can maintain the ability of FL-p53 to bind to DNA and the balance of the multiple search modes in FL-p53, leading to the maintenance of the search distance of FL-p53 against [Mg2+]. The CT domain is known to anchor FL-p53 on DNA and promotes the sliding of FL-p53 along DNA (7). This study further clarifies an additional crucial role of the CT domain: the maintenance of the target search of FL-p53 by likely interacting with the core domain.

Materials and Methods

Expression and purification of the CoreTet and TetCT mutants

The expression and purification of CoreTet and TetCT of human p53, which lack the CT and core domains, respectively (Fig. 1), were conducted by the method used in our earlier study, with some modifications (11). The artificially synthesized genes (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan) for CoreTet corresponding to residues 1–363 of the thermostable and cysteine-modified mutant of human p53 (C124A, C135V, C141V, W146Y, C182S, V203A, R209P, C229Y, H233Y, Y234F, N235K, Y236F, T253V, N268D, C275A, C277A, and K292C), and for TetCT corresponding to residues 293–393 of human p53 with an additional N-terminal cysteine, were inserted into the pGEX-6P-1 plasmid. CoreTet and TetCT possess an additional sequence, GPLGS, at the N-terminus. The plasmid encoding CoreTet or TetCT was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells. The cells were cultured in 1 L of 2× YT medium at 37°C. After OD600 reached 0.6, IPTG and ZnCl2 were added to the final concentration of 100 μM for CoreTet. For TetCT, ZnCl2 was not added to the cell culture because TetCT does not possess the binding site for Zn2+. The culture was incubated at 20°C for 20 h. The cells were then collected and suspended in 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 650 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, and 10 U/mL DNase at pH 7.4 and lysed by sonication. After incubation for 30 min on ice, the suspension of the lysed cells was centrifuged and the supernatant was collected. The supernatant containing CoreTet or TetCT with GST tag was loaded onto a GST column (GSTrap FF; GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan). The GST tag was cleaved by PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) and the mutants were collected from the column. The sample was purified further using a heparin column (HiTrap Heparin HP; GE Healthcare). The expression and purity of CoreTet and TetCT were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Equilibrium titration measurements

To examine the equilibrium binding of CoreTet and TetCT to DNA by fluorescence anisotropy, we used a fluorescence spectrometer (FP-6500; Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) with an automatic titration accessory (ATS-443; Jasco) and a home-built autorotating polarizer unit, as reported in Murata et al. (11). The CoreTet and TetCT mutants were respectively titrated in the solution of 5 nM 6-FAM-DNA in 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and 50 mM KCl, and various concentrations of MgCl2 at pH 7.9 and at 25°C. The sequence of specific DNA (spDNA) for p53 was 5′-6-FAM-ATCAGGAACATGTCCCAACATGTTGAGCTC-3′ (Sigma-Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan). The underlined part is the p21 promoter corresponding to one of the targets of p53. The sequences of nonspecific DNA were 5′-6-FAM-AATATGGTTTGAATAAAGAGTAAAGATTTG-3′ termed “random-nspDNA”, and 5′-6-FAM-ATCGAACTAGTTAACTAGTACGCAA-3′ termed “TrpR-nspDNA” (Sigma-Aldrich) (25). The respective excitation and emission wavelengths were 480 and 525 nm. A long-pass filter, which passes wavelengths longer than 500 nm, was set before the detector. The fluorescence anisotropy r was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where IVV and IVH, respectively, represent the fluorescence intensity excited at the vertical polarization and detected at the vertical polarization and the intensity excited at the vertical polarization and detected at the horizontal polarization. A factor G was obtained from IHH and IHV. The obtained titration curves were analyzed using a standard two-state model, in which one tetramer p53 binds to one DNA. For fitting of the data, we used Eqs. 2 and 3 as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where robs, rD, rpD, KD, cp, cD, and cpD denote the observed anisotropy, the anisotropy of free DNA, the anisotropy of the complex between the p53 mutant and DNA, the dissociation constant, the total concentration of the tetrameric p53 mutant, the total concentration of DNA, and the concentration of the p53-DNA complex, respectively.

Stopped-flow measurements

We used the stopped-flow fluorescence anisotropy apparatus described in an earlier report (11) to assess the kinetic dissociation of CoreTet and TetCT from DNA. A solution of 6-FAM-DNA and the p53 mutant at the final concentration of 20 and 30 nM per tetramer, respectively, were mixed with a solution of nonlabeled spDNA at the final concentration of 200 nM in the stopped-flow device. Both solutions contained 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 50 mM KCl, and various concentrations of MgCl2 at pH 7.9 and at 25°C. A laser beam at 473 nm (Laser Quantum, Stockport, Cheshire, UK) was aimed at the observation cell of the stopped-flow apparatus (Unisoku, Osaka, Japan) after passing through a polarizer (Edmund Optics, Tokyo, Japan). After mixing, the fluorescence passing through a polarizer and a band-pass filter (FF01-520/35; Semrock, Rochester, NY) was detected using a photosensor (H10722; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Four traces of IVV and IVH were measured independently and averaged. Using the averaged traces of IVV and IVH, the traces of fluorescence anisotropy were calculated using Eq. 1. The apparent dissociation rate constants of the p53 mutants from DNA were obtained by fitting the traces of fluorescence anisotropy with a single exponential function.

Labeling of fluorescent dye

For single-molecule measurements, CoreTet and TetCT were labeled with ATTO532 (ATTO-TEC, Siegen, Germany), based on a maleimide chemistry. The labeling reaction was conducted by mixing the p53 mutants and ATTO532 at 50 and 250 μM, respectively, in 20 mM sodium phosphate and 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.0 and at room temperature for 60 min. After the reaction, the p53 mutants labeled with ATTO532 were purified using a cation exchange column (HiTrapTM SP HP; GE Healthcare). The labeling ratio of CoreTet was 1.5 dyes per monomer of the mutant determined from the optical absorbance at 280 and 532 nm.

Construction of the DNA garden in flow cells

For a high-throughput analysis of single-molecule measurements, arrays of stretchable DNAs, termed the “DNA garden”, were produced on the surface of a flow cell, based on the procedure of microcontact printing reported by our group, with some modifications (49). To prevent nonspecific adsorption of DNA and p53 on the substrate, 0.2% MPC polymer (Lipidure-CM; NOF, Tokyo, Japan) in ethanol was applied on the surface of a coverslip (Matsunami Glass Industry, Osaka, Japan) and dried. The custom-made PDMS stamp (Fluidware Technologies, Saitama, Japan) had 31 rectangular blocks with 2 μm width, 500 μm length, and 2 μm height, placed at 14 μm intervals. The mixture of 1 mg/mL NeutrAvidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 0.05 mg/mL streptavidin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 633 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was applied on the surface of the PDMS stamp. After incubation for 5 min and covering with plastic wrap (Asahi Kasei, Tokyo, Japan), the PDMS stamp was washed with distilled water and dried. For microcontact printing of NeutrAvidin and streptavidin on the coverslip, the PDMS stamp was pressed to the MPC-coated coverslip for 5 min. After the printing, a flow cell was constructed by assembling double-sided tape, the coverslip, and the slide glass, as described in Murata et al. (11). The respective width and height of the flow path were ∼4 and 0.1 mm. A solution of 5% polyvinylpyrrolidone K15 (Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI), Tokyo, Japan) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was introduced to the flow cell and incubated for 20 min. Subsequently, 1 mg/mL BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was introduced to the flow cell and incubated for 20 min. Biotin-labeled λDNA in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was introduced to the flow and immobilized on the NeutrAvidin-printed area of the inner surface of the flow cell. For biotinylation, 7.5 μM λDNA (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was annealed using 5′-GGGCGGCGACCT-biotin-3′ (Sigma-Aldrich) at 75 nM.

Single-molecule measurements of the p53 mutants, using the DNA garden

Movements of CoreTet and TetCT labeled with ATTO532 along DNA were observed by home-built total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, as described in an earlier report (11). Briefly, output of the 532 nm laser (CL532-050-L; CrystaLaser, Reno, NV) illuminated the flow cell with total-internal reflection mode, using an objective lens with N.A. = 1.4 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence from the p53 mutants was collected by the same objective lens and detected by the TDI-EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan). The p53 mutants at 0.1–5 nM in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mg/mL BSA, 2 mM Trolox, 50 mM KCl, and various concentrations of MgCl2 at pH 7.9 was introduced into the flow cell with the DNA array by a syringe pump (Chemyx, Stafford, TX). Single-molecule experiments were performed at 23°C immediately after the dilution of CoreTet and TetCT from the stock solution at several tens of μM and completed within 50 min to prevent dissociation of the tetramer (50).

Analysis of single-molecule data

To obtain the trajectories of the p53 mutants from the movie, we followed a method developed in our previous study (11). Briefly, the particle track and analysis, which are in the ImageJ software plugin (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), were used to track the center of the fluorescent spots, based on 2D Gaussian fitting. We selected the trajectories satisfying the following criteria. First, the trajectories lasting longer than 500 ms were selected. Second, to remove the adsorbed molecules on the substrate, the trajectories that showed movement due to DNA fluctuation were selected by analyzing movement along the traverse axis against the DNA. Third, to exclude connection of different molecules into one trajectory, trajectories showing displacement >300 nm during 33 ms were excluded.

Results

Construction of p53 mutants

We prepared two deletion mutants of human p53 in which one of two DNA-binding domains was deleted—CoreTet and TetCT, which, respectively, lacked CT and core domains (Fig. 1). CoreTet was the construct containing residues from the first to 363rd of the thermostable mutant of FL-p53 used in our previous study (11). The thermostable mutant was based on ST7 reported previously (29), containing C124A, C135V, C141V, W146Y, C182S, V203A, R209P, C229Y, H233Y, Y234F, N235K, Y236F, T253V, N268D, C275A, and C277A. In addition, a cysteine, K292C, was introduced for the labeling of fluorophore in CoreTet. TetCT had 293rd to 393rd residues of FL-p53. An additional cysteine, 292C, was introduced at the N-terminus of TetCT as the labeling site of a fluorescence dye. CoreTet and TetCT with GST-tag were expressed in E. coli, purified by GST column after the cleavage of the GST-tag and further purified by heparin column as described in Murata et al. (11). We confirmed the tetrameric conformation of both CoreTet and TetCT by using gel electrophoresis under the native condition (Fig. S1).

To examine the DNA binding of CoreTet and TetCT, we conducted fluorescence anisotropy measurements using an automatic titrator and automatic rotator of polarization plate coupled to a standard fluorometer (11). The CoreTet and TetCT mutants were added to the solution containing nonspecific (random-nspDNA) or specific DNA (spDNA) labeled with a fluorescence dye, 6-FAM, in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ and 50 mM K+ (Fig. S2). The titration curves were well fitted to a two-state model in which one tetramer binds to one DNA with a dissociation constant, KD (Eqs. 2 and 3). The KD values of the two mutants and FL-p53 are listed in Table S1. The KD value for the pair of CoreTet and spDNA was much smaller than the KD for the pair of CoreTet and nspDNA, suggesting that CoreTet possesses the specific binding to DNA. By contrast, the difference of the KD values in TetCT for spDNA and nspDNA was much smaller than that in CoreTet. These results suggest that CoreTet and TetCT maintain the specific and nonspecific binding to DNA, respectively.

Effects of Mg2+ on nonspecific binding of CoreTet and TetCT to DNA

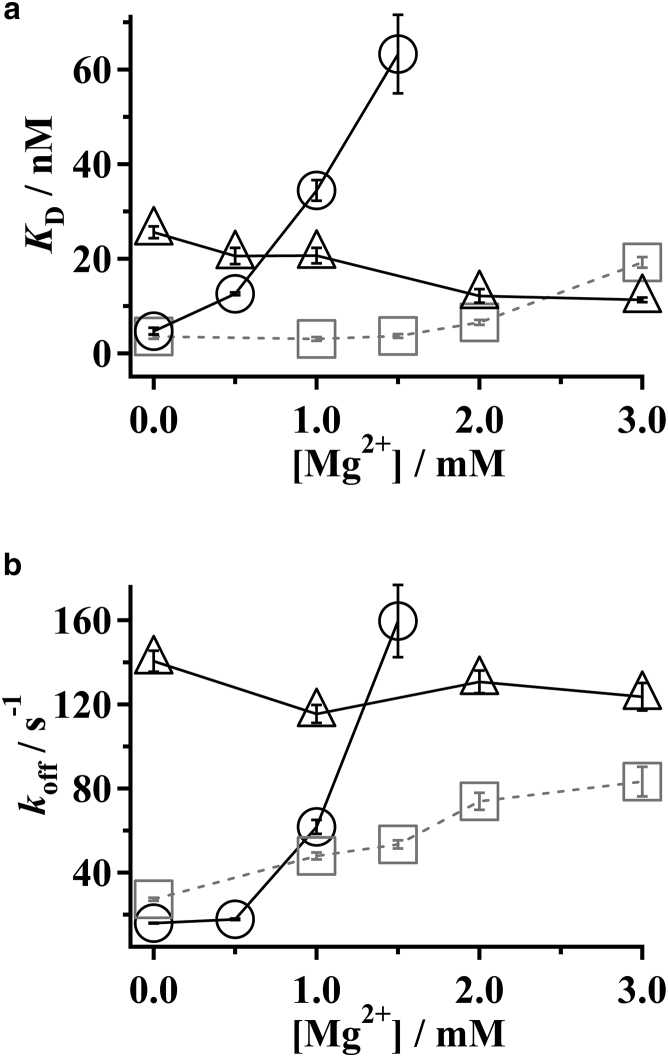

To investigate the effects of divalent cations on different domains of p53, we investigated the dependence of KD of CoreTet and TetCT on [Mg2+] in the presence of 50 mM K+. Titration curves of CoreTet and TetCT against random-nspDNA were obtained at various [Mg2+] (Fig. S3). The titration curves were well fitted to Eqs. 2 and 3. The KD value of CoreTet increased dramatically along with the increase of [Mg2+] (Fig. 2 a; Table S2). By contrast, KD of TetCT was less sensitive. It decreased slightly along with the increase of [Mg2+] (Fig. 2 a; Table S2). Binding of CoreTet was stronger than that of TetCT at [Mg2+] below 0.5 mM. In contrast, upon the addition of Mg2+, CoreTet binding became weaker, although that of TetCT was not altered. Consequently, at [Mg2+] higher than 1 mM, KD for CoreTet and TetCT were reversed, rendering the binding of CoreTet weaker than that of TetCT.

Figure 2.

(a) Shown here is the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD, of FL-p53, CoreTet, and TetCT from nspDNA at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. (b) Shown here is the kinetic dissociation rate constant, koff, of FL-p53, CoreTet, and TetCT from nspDNA at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. In (a) and (b), solid circles and triangles signify data of CoreTet and TetCT, respectively. Shaded squares denote data of FL-p53 obtained in our previous study (11). Error bars show the fitting error.

To further confirm the above results for nspDNA having a different sequence, we prepared the second nonspecific DNA, TrpR-nspDNA, which contains the binding sequence for TrpR but is nonspecific for p53, and titrated CoreTet and TetCT at various [Mg2+] (Fig. S4, a and b). The KD value for TrpR-nspDNA of CoreTet increased at [Mg2+] higher than 1.5 mM, whereas the KD of TetCT was insensitive to [Mg2+] (Fig. S4 c). The results for TrpR-nspDNA showing Mg2+ dependence are similar to those obtained for random-nspDNA. Accordingly, the effect of [Mg2+] on the KD for CoreTet and TetCT does not depend on the nspDNA sequence.

We next measured the dissociation kinetics of CoreTet and TetCT from random-nspDNA, using stopped-flow fluorescence-anisotropy apparatus (11). The fluorescence anisotropy of the labeled nspDNA, initially bound to these mutants, decreased after mixing with an excess amount of nonlabeled spDNA, corresponding to the dissociation of p53 from nspDNA. We measured the kinetics at various [Mg2+] in the presence of 50 mM K+, and fitted the obtained time courses with a single exponential function to estimate the rate constant for the dissociation: koff (Fig. 2 b; Fig. S5). The koff values of FL-p53 and the two mutants are listed in Table S2. The koff of CoreTet increased with the increase of [Mg2+]. By contrast, the koff values of TetCT were not altered at [Mg2+] between 0 and 3 mM. Consequently, although the changes in KD and koff for CoreTet were detected, they were not observed for TetCT at similar [Mg2+]. Accordingly, the results demonstrate that changes in [Mg2+] affect the properties of each p53 domain differently.

One can understand that the reported KD and koff values of FL-p53 at various [Mg2+] are the sum of the individual contributions of the two DNA-binding domains (11). As shown in Fig. 2, a and b, the KD and koff of FL-p53 were equivalent to or smaller than those of CoreTet and TetCT at 0–3 mM Mg2+, suggesting that both the core and CT domains contribute to FL-p53 binding to nspDNA. At [Mg2+] below 1 mM, the core domain binds to nspDNA tighter than the CT domain because the KD and koff of the CoreTet mutant are smaller than those of TetCT. By contrast, at [Mg2+] higher than 1 mM, although mutual interaction between the core domain and DNA becomes weaker, the CT domain retains interaction to nspDNA. Therefore, the disordered CT domain becomes more important for FL-p53 and DNA interaction at the higher [Mg2+].

Effect of Mg2+ on the 1D search of CoreTet

By TIRF microscopy (11), we next examined the 1D search dynamics of CoreTet along the extended λDNA. We introduced CoreTet labeled with ATTO532 into the flow cell, in which the λDNA array was prepared using the DNA garden technique based on microcontact stamping (49). Because λDNA does not contain target sites for p53, the observation corresponds to the 1D-sliding dynamics along a nonspecific DNA sequence. The fluorescent spots of the p53 mutants were imaged by TIRF microscopy and recorded by TDI-EM-CCD at the time interval of 33 ms. After the data acquisition, we tracked all fluorescent spots in the area except for the stamped area in all the frames and chose molecules sliding along DNA (11). We observed CoreTet at various [Mg2+] in the presence of 50 mM K+, and obtained 91–514 trajectories for each condition (Fig. 3 a). Time courses of the averaged mean square displacement (MSD) calculated from the obtained trajectories are presented in Fig. 3 b), and we confirmed the linear relation between MSD and the time interval within 165 ms at all [Mg2+], indicating that CoreTet moves along DNA in a diffusive manner. The averaged diffusion coefficient D was obtained by fitting the slope of the MSD plots within 165 ms. In the presence of 2 mM Mg2+ and 50 mM K+, the average D value was 0.063 ± 0.003 μm2 s−1, which was significantly smaller than that of FL-p53 obtained in the same experimental condition (0.128 ± 0.004 μm2 s−1). A smaller D value for the mutant without the CT domain compared to that of FL-p53 was similarly reported by Tafvizi et al. (7).

Figure 3.

(a) Shown here are typical single-molecule trajectories of the 1D search of CoreTet along nonspecific DNA observed at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Top, middle, and bottom panels present data obtained in the presence of 0, 1, and 2 mM Mg2+, respectively. Several traces were colored for clarity. (b) Time courses of the averaged MSD of CoreTet were observed at the various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Red, green, and blue circles denote averaged MSD values in the presence of 0, 1, and 2 mM Mg2+, respectively. The errors of the average are the standard error. (c) Diffusion coefficients of CoreTet at the various [Mg2+] are given. Solid and dashed lines, respectively, show data obtained in the presence and the absence of 50 mM K+. To see this figure in color, go online.

We show the dependence of the averaged D values of CoreTet on [Mg2+], as calculated from MSD plots obtained in the presence of 50 mM K+ (Fig. 3 c). It could be expected that the 1D search of CoreTet is promoted by the Mg2+ addition because of the increase of the KD and koff of CoreTet at the increased [Mg2+] (Fig. 2). However, CoreTet showed complex dependency of D on [Mg2+] (Fig. 3 c). The averaged D was unaffected by the increase of [Mg2+] up to 1 mM. At [Mg2+] higher than 1 mM, the averaged D values decreased dramatically. We also observed the 1D search dynamics of CoreTet in the absence of K+ and showed the dependence of the averaged D values on [Mg2+] (Fig. 3 c; Fig. S6). A decrease of D was also observed at 1 mM Mg2+ in the absence of K+ (Fig. 3 c). In addition, the D value at 0 mM Mg2+ in the absence of K+ was small. These results demonstrate that the 1D search of CoreTet is suppressed at higher [Mg2+].

Two search modes of CoreTet

We next analyzed the displacement distribution of the 1D search of CoreTet at a fixed time interval. For the case of FL-p53, our previous report described that the displacement distribution can be expressed as the sum of two Gaussian functions, and suggested that the fast and slow diffusion modes are present for FL-p53 (11). Because the slow mode disappeared in TetCT, we surmised that the two modes might result from the multiple tertiary structures of the p53-DNA complex (11). Accordingly, we expected that CoreTet might also possess multiple diffusion modes, which might be regulated further by the divalent cations. In fact, the displacement distributions for CoreTet at 0 and 1 mM Mg2+ in the presence of 50 mM K+ showed heterogeneous distributions deviating from the single Gaussian (Fig. 4, a and b; Table S3). The observed distributions were well fitted by a sum of two Gaussians with different diffusion coefficients and drift velocities, as expressed in the following:

| (4) |

where Δt, Δx, Ai, Vi, and Di denote the time interval, the displacement of p53 in the time interval, the amplitude of the ith component, the drift velocity of the ith component, and the diffusion coefficient of the ith component, respectively. Therefore, we conclude that the fast and slow diffusion modes are similarly present for CoreTet.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Given here are displacement distributions for the sliding dynamics of CoreTet at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Shaded bars represent the displacement distributions observed at the time interval of 165 ms. (a), (b), and (c) present the distributions at 0, 1, and 2 mM Mg2+, respectively. Solid curves are best-fitted curves obtained using Eq. 1. Dashed curves in (a) and (b) represent the distributions of each mode. (d) Given here is the fraction of the fast mode of CoreTet and of the fast-I/fast-II mode of FL-p53 at the various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Solid circles denote data of CoreTet. Shaded squares denote data of FL-p53 obtained in our previous study (11).

The multiple components corresponding to the fast and slow modes were also verified in the distribution of the apparent diffusion coefficient calculated from the slope of the MSD plot of each single-molecule trajectory (Fig. S7). Owing to the small number of data points in a single trajectory, the distribution of the apparent diffusion coefficient is broad. However, in addition to the slow mode showing a single peak near 0.025 μm2 s−1, the fast mode was observed as a broad peak having the center at ∼0.2 μm2 s−1 at 0−1 mM Mg2+ plus 50 mM K+. The presence of the fast mode was confirmed by its disappearance for the data observed at 2 mM Mg2+ plus 50 mM K+ and at 1 mM Mg2+ in the absence of K+ (Figs. S7 b and S8; Table S3). Thus, the presence of the multiple diffusion modes was justified by the different method of the data analysis.

We next investigated the effect of [Mg2+] on the two diffusion modes of CoreTet in the presence of 50 mM K+. In the absence of Mg2+, the respective D values in the fast and slow modes were 0.213 ± 0.009 and 0.047 ± 0.004 μm2 s−1. Furthermore, the respective drift velocities in the fast and slow modes were 0.43 ± 0.03 and 0.09 ± 0.02 μm s−1. The fast mode fraction was 58 ± 4%. In contrast, the displacement distribution at 2 mM Mg2+ was fitted by a single Gaussian (Fig. 4 c; Table S3). The D value and the drift velocity were, respectively, 0.054 ± 0.003 and 0.08 ± 0.02 μm s−1. Consequently, only the slow diffusion mode was observed at the high [Mg2+]. The fast mode fraction decreased considerably, as with the increase of [Mg2+] (Fig. 4 d). Disappearance of the fast mode at the higher [Mg2+] in CoreTet apparently decreased the averaged D value (Fig. 3 c). These results suggest that the interaction between the core domain and DNA changes sensitively with [Mg2+], slowing the 1D search of p53 at higher concentrations of these ions.

To examine if the complex dependence of the 1D search is specific for Mg2+, we next measured 1D diffusion of CoreTet along DNA at various [K+] in the absence of Mg2+. The averaged D value increased with the increase of [K+] up to 50 mM, and then decreased at 75 mM K+ (Fig. S9 a). The displacement distributions obtained at 10−50 mM K+ in the absence of 0 mM Mg2+ were explained by the sum of two Gaussian functions, indicating the presence of the two modes (Fig. S9 b). The similarity of the overall behavior of the 1D diffusion observed at different [K+] and that at different [Mg2+] suggests that the 1D search of CoreTet might be tuned by an electrostatic interaction between the core domain and DNA. It should be noted that the concentration range showing the changes in the diffusion coefficient for Mg2+ (∼1 mM) is much smaller than that observed for K+ (∼50 mM).

Effects of Mg2+ on the 1D search of TetCT

We next investigated the 1D search dynamics of TetCT along DNA at various [Mg2+] in the presence of 50 mM K+. Considering the weak dependence of the KD and koff of TetCT on [Mg2+], we expected that the diffusive motion of TetCT would be less affected by Mg2+ addition. In fact, our previous study found simple diffusion of TetCT at 2 mM Mg2+ plus 50 mM K+ (11). For each condition, 114–187 trajectories were obtained (Fig. 5 a). The averaged MSDs, as calculated from the single-molecule trajectories of TetCT, exhibited a linear relation against the time interval, demonstrating that the dynamics of TetCT was diffusive for [Mg2+] of 0–3 mM (Fig. 5 b). Averaged D values were obtained by fitting of the MSD plots within 165 ms. At 2 mM Mg2+ and 50 mM K+, D of the TetCT mutant was 0.66 ± 0.01 μm2 s−1, which was identical to that obtained in an earlier study (0.776 ± 0.098 μm2 s−1) (7). The averaged D value increased slightly upon the increase of [Mg2+] up to 2 mM Mg2+ and was saturated at above 2 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 5 c). Considering that the KD and koff were unaffected by [Mg2+] (Fig. 2), the search dynamics of TetCT was independent of the affinity of the CT domain to DNA. The displacement distributions exhibited a single Gaussian distribution, thereby confirming the absence of the slow diffusion mode in TetCT (Fig. S10; Table S3). The distribution of diffusion coefficient calculated from the MSD plot of single trajectories is broad, owing to the limited data points per trajectory (Fig. S11); however, the absence of the sharp peak at 0.025 μm2s−1, detected for the corresponding distribution of CoreTet (Fig. S7 a), is consistent with the absence of the slow mode in TetCT. These results confirm that interaction between the core domain and DNA causes the slow mode of p53 at various [Mg2+].

Figure 5.

(a) Typical single-molecule trajectories of TetCT along nonspecific DNA are observed at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Top, middle, and bottom panels present data obtained in the presence of 0, 1, and 2 mM Mg2+, respectively. Several traces are colored for clarity. (b) Shown here are time courses of the averaged MSD of TetCT at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Red, orange, green, and blue circles denote the averaged MSD values in the presence of 0, 1, 2, and 3 mM Mg2+, respectively. The errors of the average are the standard errors. (c) Shown here are the averaged diffusion coefficients of TetCT at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. To see this figure in color, go online.

Different oligomeric states cannot explain the two modes in CoreTet and FL-p53

To examine a possible involvement of different oligomeric states such as dimer and tetramer in the two modes of CoreTet and FL-p53, we introduced the mutation L344A in the Tet domain of FL-p53 and prepared a dimer-forming mutant (FL-p53-L344A) (Supporting Materials) (25, 51, 52, 53). The affinity of FL-p53-L344A to nspDNA was significantly reduced, whose KD for random-nspDNA could not be quantified but was larger than 130 nM per dimer, a value at least eightfold larger than that for FL-p53 (Fig. S12). The data strongly suggest that the dimeric components of FL-p53 or CoreTet, if any, would not be detected in this experimental condition where the sample concentration was optimized for the detection of the tetrameric form. Furthermore, the tetrameric forms of CoreTet and FL-p53, confirmed in native-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. S1), were maintained during the single-molecule experiments because the experiments were finished before the transition from tetramer to dimer occurred (50). In addition, the heterogeneity of the 1D diffusion in TetCT was not observed despite the integrity of the tetramerization domain in CoreTet, TetCT, and FL-p53 (Fig. S10). Accordingly, we ruled out the possibility that the dimeric form of CoreTet and TetCT caused the heterogeneity of 1D diffusion observed in the single-molecule measurements. As we will explain below, the conformational change in the tetramer form of CoreTet and FL-p53 can consistently explain the multiple modes in 1D diffusion along DNA.

Discussion

This study examined the roles of each domain in the maintenance of the target search dynamics of p53 reported in our previous study (11). Results showed that the CT domain enabled maintenance of the binding of FL-p53 to DNA at various [Mg2+], because both the KD and koff of TetCT were less dependent on [Mg2+], as similarly observed for FL-p53 (Fig. 2). We further clarified that the average D value of the CT domain was less sensitive to the changes in [Mg2+] (Fig. 5), but that of the core domain changed dramatically according to changes in [Mg2+] (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the CT domain contributes to the maintenance of the search dynamics of FL-p53 in various cell conditions. The 1D diffusion of FL-p53 consists of multiple modes reflecting the different structures of the p53-DNA complex (11). At low [Mg2+], the fast-I and slow modes were observed. At high [Mg2+], the fast-II and slow modes were observed. Although the fraction of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes for FL-p53 was not altered at varying [Mg2+], the fraction was strongly dependent on [Mg2+] for CoreTet (Fig. 4). This observation suggests that the absence of the CT domain disturbs the balance of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes. It has been proposed that the role of the CT domain is in the nonspecific attachment of FL-p53 to DNA, enabling its sliding along DNA. This study further reveals the important function of the CT domain, in which it maintains the target search dynamics of p53 by retaining the binding to DNA, the 1D search dynamics, and the equilibrium balance of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes. We discuss below the molecular mechanism of the Mg2+ dependence of each domain, the quaternary structure models for three search modes of FL-p53, and the roles of the CT domain in the maintenance of the target search dynamics of p53.

Distinct Mg2+-dependence of two DNA-binding domains may be attributed to their structural properties

Mg2+ did not affect the equilibrium and kinetic dissociation constants for the binding of TetCT to DNA, which differed from the significant Mg2+ dependence of these constants of CoreTet (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the 1D search dynamics of TetCT was enhanced upon the elevation of [Mg2+], but that of CoreTet was suppressed (Figs. 3 and 5). The different dependence between TetCT and CoreTet for the nonspecific binding to and 1D search dynamics along DNA might be attributed to the distinct structural difference of the two DNA-binding domains. Although the core domain possesses a specific folded structure, the CT domain is intrinsically disordered.

The observed behavior of p53 at different [Mg2+] may be attributed to the partial association of Mg2+ to DNA. Mg2+ of approximately millimolar concentrations binds directly to the nucleotide or phosphate groups of DNA (46, 48), which can weaken the electrostatic interaction between the DNA-binding domains of p53 and DNA. The binding of Mg2+ to DNA was not saturated at 20 mM Mg2+ (44), suggesting that the negative charges of DNA were not fully neutralized in our experimental range from 0 to 3 mM Mg2+. There is a possibility that Mg2+ may associate to some of the six histidine residues in the core domain and to three histidine residues in the CT domain (54). However, the binding of Mg2+ to p53 should increase its positive net charge and strengthen the electrostatic interaction between p53 and DNA, which was not detected in the KD of CoreTet and TetCT for nspDNA as well as that of FL-p53 (Fig. 2). No evidence has been reported supporting the binding of Mg2+ or Ca2+ to p53, except for the binding of Mg2+ to the open binding site of Zn2+ only after the removal of the tightly bound Zn2+ (55). Results of the electrophoresis indicates that the oligomeric state of p53 was not altered by the addition of Mg2+ (Fig. S1). Accordingly, the direct binding of Mg2+ to p53, if any, does not explain the observed behavior of p53. Finally, the addition of 3 mM Mg2+ corresponded to only a 0.2-fold increase of the total ionic strength of the solution containing 50 mM KCl. In addition, much higher [K+] was necessary to have a similar effect on the diffusion coefficient of CoreTet observed at different [Mg2+] (Fig. 3; Fig. S9). Therefore, the effect of different [Mg2+] examined in this study is expected to be attributed to the partial association of Mg2+ to the negatively charged phosphate group of DNA.

The strong dependence of CoreTet on [Mg2+] can be attributed to the diminished interaction between the core domain and DNA at [Mg2+] higher than 1 mM. The core domains are known to form specific contacts to the target sequence of DNA (29, 56, 57, 58, 59), suggesting that the core domain interacts with nonspecific DNA, using the same region used in the specific binding (9). This interaction might be disturbed by the partially associated Mg2+ on DNA. In contrast, to explain the independence of TetCD from [Mg2+], we suggest that the disordered CT domain enables avoidance of the region of DNA where Mg2+ is bound and enables association to the Mg2+-unbound region. The flexibility of the CT domain might contribute to avoidance of the Mg2+-bound region. In fact, many DNA-binding proteins possess disordered DNA-binding domains similar to the CT domain (60). The effect of divalent cations on the affinity of these proteins to DNA, which has not yet been examined, is expected to be important.

Structural insight of the p53-DNA complex in the two search modes

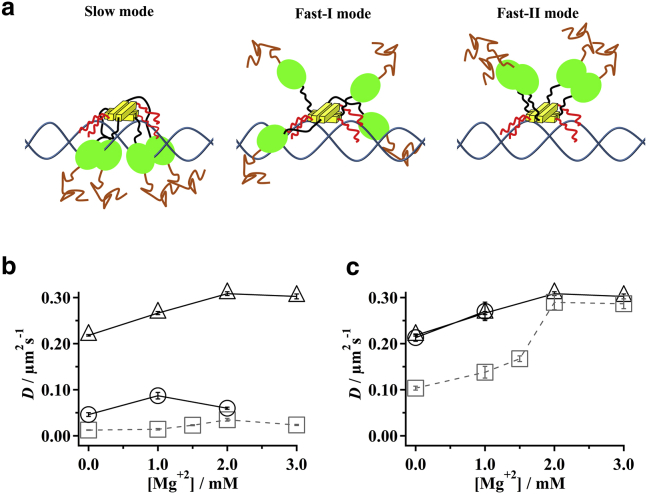

We reported earlier that FL-p53 possesses multiple search modes with different diffusion coefficients. Moreover, we suggested that multiple modes result from different quaternary structures of the p53-DNA complex (11). These results further suggest that the search dynamics of FL-p53 at different [Mg2+] might be maintained using the interplay of different search modes. Multiple search modes were observed in other DNA-binding proteins, including the LacI repressor (14), E. coli replisomes (61), DNA glycosylases (62), and transcription activator-like effector proteins (63). However, the conformational and functional properties of each mode in these proteins remain poorly understood except for DNA glycosylases, in which wedge residues such as Phe, Tyr, and Leu are inserted into the DNA duplex to search for damaged sites in DNA and to cause a heterogeneous distribution of the diffusion coefficient (64, 65). To explain the multiple modes observed in p53, we propose a model based on three quaternary structures in the association structure of p53 sliding along the nonspecific DNA.

We hypothesize that p53 sliding along DNA can possess three quaternary structures having different domain arrangements. In the slow mode, we infer that p53 possesses the maximal contact to DNA, using the core and CT domains. In the structural model shown in the left of Fig. 6 a, we show that all core domains are in contact with DNA. It is noteworthy, however, that the structure is hypothetical and the number of the core domains in contact with DNA might be different. In the fast mode, the model includes the assumption of two additional quaternary structures. In the fast-I mode detected at lower [Mg2+], some core domains associate weakly with DNA. The CT domain retains contact with DNA. In the middle of Fig. 6 a, we depict a hypothetical structure of the fast-I mode with two core domains associating to DNA. In fact, the fast-I mode may be composed of an ensemble of heterogenic structures containing complex contacts between the domains or between the domain and DNA as predicted in molecular dynamics simulation (8, 9). In the fast-II mode detected at higher [Mg2+], p53 is in contact with DNA, using only the CT domain, as shown at the right of Fig. 6 a. In the case for FL-p53, a mixture of the slow mode and the fast-I mode was detected at low [Mg2+]. At higher [Mg2+], the fast-I mode of FL-p53 changed to the fast-II mode while maintaining the same fraction of the slow mode. In the case for CoreTet, the mixture of the fast-I mode and the slow mode was detected at low [Mg2+]. At higher [Mg2+], only the slow mode could be identified. In the case for TetCT, only the fast-II mode was detected at all [Mg2+]. As we will discuss below, the three-state model can explain the observed data consistently.

Figure 6.

(a) Given here is a schematic diagram of the three search modes of FL-p53. Brown lines, green ellipsoids, black lines, yellow blocks, and red lines show the N-terminal domains, core domains, linkers, Tet domains, and CT domains of p53, respectively. Blue lines represent dsDNA. In the slow mode, p53 possesses the maximal contacts of the core and CT domains to DNA and the interaction between the core domains (left). In the fast-I mode observed at lower [Mg2+], p53 possesses loose contacts of the core domains to DNA and the tight contacts of the CT domain to DNA (middle). In the fast-II mode observed at higher [Mg2+], only the tight contacts of the CT domains to DNA are present (right). (b) Given here are the size-corrected diffusion coefficients of the slow mode for CoreTet and FL-p53 at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Gray squares and black circles, respectively, denote the data of FL-p53 and CoreTet. Triangles mark data of the fast mode of the TetCT mutant for comparison. (c) Given here are the size-corrected diffusion coefficients of the fast mode for CoreTet and TetCT and of the fast-I and fast-II modes for FL-p53 at the various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Gray squares, black circles, and black triangles signify data of FL-p53, CoreTet, and TetCT, respectively. In (b) and (c), errors represent the standard error. The FL-p53 data were obtained in our previous study (11). To see this figure in color, go online.

To support the three-state model, we compared the diffusion coefficients of the slow, fast-I, and fast-II modes of FL-p53 to the corresponding modes in CoreTet and TetCT (Fig. 6, b and c). For comparison, we used the size-corrected diffusion coefficient, Dcorr, of TetCT using a size factor of 0.45 (7), which was estimated using the mutant size (57) and rotational motion along the helical path of DNA. In the slow mode depicted in Fig. 6 b, the D values for CoreTet and FL-p53 were much smaller than the D value for TetCT in the fast-II mode, suggesting that the core domains were associated with DNA in FL-p53. Furthermore, the lower D value for FL-p53 than that of CoreTet might be consistent with the additional contacts with DNA in FL-p53, using the CT domain. A similar relation was observed for the fast-I mode observed at low [Mg2+] (Fig. 6 c). The D value of the fast-I mode of FL-p53 was smaller than that of CoreTet, suggesting partial association of the core domain and the association of the CT domain to DNA in FL-p53. At higher [Mg2+], the D values of the fast-II mode of FL-p53 and TetCT were almost identical, suggesting that both associate to DNA using only the CT domain. The increased diffusion of FL-p53 in the fast-II mode compared to that in the fast-I mode can be interpreted by the dissociation of the core domain at the increased [Mg2+].

The three-state model is also consistent with the increase of the KD and koff values for CoreTet at the increased [Mg2+]. We demonstrated that the association of the core domain to DNA became weaker at the increased [Mg2+], although that of the CT domain was less dependent on Mg2+. This model is consistent with the observation and assumes the decrease of the number of the core domains in contact with DNA at increased [Mg2+]. The fast-I mode of CoreTet disappeared at 2 mM Mg2+ because of the dissociation of the core domain from DNA at higher [Mg2+] (Fig. 4). Contrary to the weaker binding of the core domain to DNA in the fast-I mode, the slow mode of CoreTet was still present at 2 mM Mg2+. We expect that the slow mode may result from the dimer formation of the core domains, which can stabilize the DNA-p53 complex by increasing the contact area of the core domains against DNA and can slow the diffusion along DNA, as suggested in an earlier molecular dynamics simulation (8). Nevertheless, the association of CoreTet to DNA becomes weaker at the higher [Mg2+].

In contrast to the observations for CoreTet, the association of FL-p53 to DNA and the fraction of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes of FL-p53 were both maintained at higher [Mg2+], suggesting the interdomain interaction in FL-p53. In Fig. 4 d, the Mg2+ dependence of the fractions of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes is shown for CoreTet and FL-p53. In CoreTet, the balance of the fast and slow modes was not maintained at different [Mg2+]. In contrast, in the case for FL-p53, the fractions of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes did not change over different [Mg2+] (11). These results suggest strongly that the CT domain regulates the equilibrium between the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes in FL-p53 at different [Mg2+]. We propose that there exists an interaction of the CT domain with the other domains, most likely with the core domain (31), and that the interaction maintains the fraction of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes in FL-p53.

To further confirm the proposed interaction between the CT domain and the core domain, we tested the hypothesis that the peptide fragment from the CT domain might bind to the core domain of p53 (31) and weaken the interaction between the core domain and DNA, thus destabilizing the slow mode having the tight association of the core domain to DNA relative to the fast-I/fast-II mode (Supporting Materials). To this end, we added the isolated peptide fragment of the CT domain to the solution containing FL-p53 and measured its 1D sliding. We expected that the added CT peptide would compete with the CT domain for the binding to the core domain, and perturb the 1D sliding of FL-p53. As expected, the average diffusion coefficient and the fraction of fast-I/fast-II mode of FL-p53 were both increased as the concentration of the CT peptide fragment increased (Fig. S13). Accordingly, these results strengthen the premise that the interaction between the core domain and the CT domain in FL-p53 likely maintains the fractions of each sliding mode nearly constant over different [Mg2+].

Roles of the disordered CT domain in the target search process of p53

Here, we summarize the roles of two DNA-binding domains for the maintenance of the target search dynamics of p53 at different [Mg2+]. We demonstrated previously that the search distance of FL-p53 is maintained for various [Mg2+] and [Ca2+] (11). Fig. 7 portrays the search distance of each mutant calculated using the koff for nspDNA and D of the 1D search. Because the koff of CoreTet at 2 mM Mg2+ cannot be obtained because of the faster dissociation, we assumed that the koff values of the mutant are the same at concentrations of 1.5 and 2 mM Mg2+. Considering that the koff of CoreTet was increased on the addition of Mg2+, the search distance of CoreTet at 2 mM Mg2+ shown in Fig. 7 should be considered as the maximum value. The search distance of CoreTet was decreased significantly with the increase of [Mg2+], whereas the corresponding distance of TetCT was not altered. The results suggest that the CT domain maintains the search distance in the conditions of cells that have lost homeostatic control of the concentration of divalent cations, primarily because of the independence of the koff and D of the CT domain.

Figure 7.

Shown here is the search distance of FL-p53, CoreTet, and TetCT along nspDNA at various [Mg2+] plus 50 mM K+. Solid circles and triangles, respectively, denote the data of CoreTet and TetCT. Shaded squares show FL-p53 data obtained in our previous study (11).

The core domain possesses specific binding ability, but the CT domain does not (24). Results of previous investigations suggested that the CT domain has a role of diffusion along DNA faster in the 1D search (7). This investigation demonstrated that the CT domain can maintain binding of FL-p53 to DNA and that it enables sliding along DNA, even at elevated [Mg2+]. As revealed in molecular dynamics simulations of p53 (8, 12, 60), the charge composition and distribution of the disordered CT domain may be important to facilitate the 1D sliding of p53. Furthermore, the interdomain contacts involving the CT domain and other domains reported elsewhere (31, 66, 67) may control the fraction of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes, which are also necessary for maintenance of the search distance of FL-p53. Considering the interaction between the CT and core domains demonstrated by Retzlaff et al. (31), the CT domain may regulate the coordination of the core domain to DNA in the sliding of p53, thereby leading to maintenance of the search dynamics. In fact, as described above, the peptide fragment dissected from the CT domain can modulate the fraction of the fast-I/fast-II and slow modes and strengthen the interaction between the core and CT domains. Accordingly, we infer that the CT domain regulates the core domain dynamics and controls the fraction of each search mode of FL-p53.

Physiological implications

Finally, we point out the need to investigate the properties of p53 in the condition further mimicking the cellular condition. We demonstrated that changes in [Mg2+] that might occur in cell cycle arrest (40) do not affect the efficiency of the target search of p53 on the isolated DNA by maintaining its 1D search distance. In fact, the range of physiological [Mg2+] in cells, estimated to be 5–30 mM for the total and 0.4–0.6 mM for the free (39), is similar to the range of [Mg2+] examined in this study. However, the changes in [Mg2+] are also known to affect the conformation and assembly of nucleosomes, and might drastically affect the dynamics of p53. In cells, nucleosomes are formed, and the distance between two adjacent nucleosomes is altered by various factors such as DNA sequence and protein concentrations (68). The nucleosome can affect the target binding of p53 depending on the target accessibility in the nucleosome (69, 70). The target accessibility on the nucleosome will be modulated by the change of [Mg2+]. In fact, the transition between unfolding and folding of the nucleosome is known to occur at [Mg2+] <2 mM and the self-assembly of nucleosomes is induced above 2 mM (71, 72). Accordingly, the change of the physiological [Mg2+] may alter the conformation and assembly of nucleosomes, thus regulating the accessibility of DNA for which p53 can search, and the target search efficiency of p53.

Conclusion

The ensemble kinetic and single-molecule fluorescence measurements for p53 mutants lacking one of two DNA-binding domains revealed that the disordered CT domain of p53 can bind to DNA irrespective of [Mg2+], and can maintain an equilibrium balance of the fast-I/ fast-II and slow modes and the p53 search distance. Results suggest that p53 modulates the quaternary structure of the complex between p53 and DNA by interdomain interactions under different [Mg2+] and it thereby maintains the target search along DNA.

Author Contributions

A.M. and K.K. designed the experiments. A.M., E.M., Y.I., and S.K. executed the experiments. A.M., Y.I., and S.K. prepared p53 samples. H.T. constructed the plasmid of FL-p53-L344A. C.I. and K.K. developed the DNA garden. A.M., S.T., and K.K. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

A.M., S.T., and K.K. thank Prof. Chun Biu Lee (Hokkaido University), Prof. Tamiki Komatsuzaki (Hokkaido University), and Prof. Shoji Takada (Kyoto University) for helpful discussions.

This work was supported in whole or part by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI No. JP26840045 (to K.K.), No. JP24113701 (to K.K.), No. JP15H01625 (to K.K.), No. JP16K07313 (to K.K.), and No. JP25104007 (to S.T.); by a grant for Basic Science Research Projects from The Sumitomo Foundation (to K.K.); by a grant from the Takeda Science Foundation (to K.K.); and by the Foundation for Promotion of Material Science and Technology of Japan (to K.K.).

Editor: Elizabeth Rhoades.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, thirteen figures, and three tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30454-X.

Contributor Information

Satoshi Takahashi, Email: st@tagen.tohoku.ac.jp.

Kiyoto Kamagata, Email: kamagata@tagen.tohoku.ac.jp.

Supporting Citations

References (73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78) appear in the Supporting Materials.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bieging K.T., Mello S.S., Attardi L.D. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:359–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckerman R., Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by p53. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000935. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joerger A.C., Fersht A.R. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53 and cancer-associated mutants. Adv. Cancer Res. 2007;97:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)97001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joerger A.C., Fersht A.R. Structure-function-rescue: the diverse nature of common p53 cancer mutants. Oncogene. 2007;26:2226–2242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joerger A.C., Fersht A.R. The tumor suppressor p53: from structures to drug discovery. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a000919. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tafvizi A., Huang F., van Oijen A.M. Tumor suppressor p53 slides on DNA with low friction and high stability. Biophys. J. 2008;95:L01–L03. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tafvizi A., Huang F., van Oijen A.M. A single-molecule characterization of p53 search on DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:563–568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khazanov N., Levy Y. Sliding of p53 along DNA can be modulated by its oligomeric state and by cross-talks between its constituent domains. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:335–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terakawa T., Kenzaki H., Takada S. p53 searches on DNA by rotation-uncoupled sliding at C-terminal tails and restricted hopping of core domains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14555–14562. doi: 10.1021/ja305369u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leith J.S., Tafvizi A., van Oijen A.M. Sequence-dependent sliding kinetics of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16552–16557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120452109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata A., Ito Y., Kamagata K. One-dimensional sliding of p53 along DNA is accelerated in the presence of Ca2+ or Mg2+ at millimolar concentrations. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:2663–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terakawa T., Takada S. p53 dynamics upon response element recognition explored by molecular simulations. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17107. doi: 10.1038/srep17107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowers D.M., Wilson G.G., Halford S.E. Measurement of the contributions of 1D and 3D pathways to the translocation of a protein along DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15883–15888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505378102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y.M., Austin R.H., Cox E.C. Single molecule measurements of repressor protein 1D diffusion on DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:048302. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.048302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnet I., Biebricher A., Desbiolles P. Sliding and jumping of single EcoRV restriction enzymes on non-cognate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4118–4127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Broek B., Lomholt M.A., Wuite G.J.L. How DNA coiling enhances target localization by proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15738–15742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804248105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherstvy A.G., Kolomeisky A.B., Kornyshev A.A. Protein–DNA interactions: reaching and recognizing the targets. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:4741–4750. doi: 10.1021/jp076432e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomholt M.A., van den Broek B., Metzler R. Facilitated diffusion with DNA coiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8204–8208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903293106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammar P., Leroy P., Elf J. The lac repressor displays facilitated diffusion in living cells. Science. 2012;336:1595–1598. doi: 10.1126/science.1221648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F., Redding S., Greene E.C. The promoter-search mechanism of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase is dominated by three-dimensional diffusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:174–181. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer M., Metzler R. In vivo facilitated diffusion model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y., Murata A., Kamagata K. Activation of p53 facilitates the target search in DNA by enhancing the target recognition probability. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:2916–2930. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols N.M., Matthews K.S. Human p53 phosphorylation mimic, S392E, increases nonspecific DNA affinity and thermal stability. Biochemistry. 2002;41:170–178. doi: 10.1021/bi011736r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinberg R.L., Freund S.M., Fersht A.R. Regulation of DNA binding of p53 by its C-terminal domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;342:801–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg R.L., Veprintsev D.B., Fersht A.R. Cooperative binding of tetrameric p53 to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinney K., Mattia M., Prives C. p53 linear diffusion along DNA requires its C terminus. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinberg R.L., Veprintsev D.B., Fersht A.R. Comparative binding of p53 to its promoter and DNA recognition elements. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ang H.C., Joerger A.C., Fersht A.R. Effects of common cancer mutations on stability and DNA binding of full-length p53 compared with isolated core domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21934–21941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petty T.J., Emamzadah S., Halazonetis T.D. An induced fit mechanism regulates p53 DNA binding kinetics to confer sequence specificity. EMBO J. 2011;30:2167–2176. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melero R., Rajagopalan S., Valle M. Electron microscopy studies on the quaternary structure of p53 reveal different binding modes for p53 tetramers in complex with DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:557–562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015520107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Retzlaff M., Rohrberg J., Buchner J. The regulatory domain stabilizes the p53 tetramer by intersubunit contacts with the DNA binding domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahirel V., Paillusson F., Victor J.M. Nonspecific DNA-protein interaction: why proteins can diffuse along DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:228101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.228101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goychuk I., Kharchenko V.O. Anomalous features of diffusion in corrugated potentials with spatial correlations: faster than normal, and other surprises. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:100601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer M., Rasmussen E.S., Metzler R. Real sequence effects on the search dynamics of transcription factors on DNA. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10072. doi: 10.1038/srep10072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulkkinen O., Metzler R. Variance-corrected Michaelis-Menten equation predicts transient rates of single-enzyme reactions and response times in bacterial gene-regulation. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17820. doi: 10.1038/srep17820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slutsky M., Mirny L.A. Kinetics of protein-DNA interaction: facilitated target location in sequence-dependent potential. Biophys. J. 2004;87:4021–4035. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tafvizi A., Mirny L.A., van Oijen A.M. Dancing on DNA: kinetic aspects of search processes on DNA. ChemPhysChem. 2011;12:1481–1489. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamagata K., Murata A., Takahashi S. Characterization of facilitated diffusion of tumor suppressor p53 along DNA using single-molecule fluorescence imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2017;30:36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartwig A. Role of magnesium in genomic stability. Mutat. Res. 2001;475:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikari A., Sawada H., Sugatani J. Magnesium deficiency suppresses cell cycle progression mediated by increase in transcriptional activity of p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) in renal epithelial NRK-52E cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:3563–3572. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brini M., Murgia M., Rizzuto R. Nuclear Ca2+ concentration measured with specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. EMBO J. 1993;12:4813–4819. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Q.L., Kondo T., Fujiwara Y. Mitochondrial and intracellular free-calcium regulation of radiation-induced apoptosis in human leukemic cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1999;75:493–504. doi: 10.1080/095530099140429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gogna R., Madan E., Pati U. Gallium compound GaQ(3)-induced Ca2+ signalling triggers p53-dependent and -independent apoptosis in cancer cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;166:617–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li A.Z., Huang H., Marx K.A. A gel electrophoresis study of the competitive effects of monovalent counterion on the extent of divalent counterions binding to DNA. Biophys. J. 1998;74:964–973. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tereshko V., Minasov G., Egli M. The Dickerson-Drew B-DNA dodecamer revisited at atomic resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:470–471. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiu T.K., Dickerson R.E. 1 Å crystal structures of B-DNA reveal sequence-specific binding and groove-specific bending of DNA by magnesium and calcium. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:915–945. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hud N.V., Polak M. DNA-cation interactions: the major and minor grooves are flexible ionophores. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmad R., Arakawa H., Tajmir-Riahi H.A. A comparative study of DNA complexation with Mg(II) and Ca(II) in aqueous solution: major and minor grooves bindings. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2460–2466. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igarashi C., Murata A., Kamagata K. DNA garden: a simple method for producing arrays of stretchable DNA for single-molecule fluorescence imaging of DNA binding proteins. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2017;90:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rajagopalan S., Huang F., Fersht A.R. Single-molecule characterization of oligomerization kinetics and equilibria of the tumor suppressor p53. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2294–2303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterman J.L., Shenk J.L., Halazonetis T.D. The dihedral symmetry of the p53 tetramerization domain mandates a conformational switch upon DNA binding. EMBO J. 1995;14:512–519. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCoy M., Stavridi E.S., Halazonetis T.D. Hydrophobic side-chain size is a determinant of the three-dimensional structure of the p53 oligomerization domain. EMBO J. 1997;16:6230–6236. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mateu M.G., Fersht A.R. Nine hydrophobic side chains are key determinants of the thermodynamic stability and oligomerization status of tumour suppressor p53 tetramerization domain. EMBO J. 1998;17:2748–2758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palecek E., Brázdová M., Vojtesek B. Effect of transition metals on binding of p53 protein to supercoiled DNA and to consensus sequence in DNA fragments. Oncogene. 1999;18:3617–3625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xue Y., Wang S., Feng X. Influence of magnesium ion on the binding of p53 DNA-binding domain to DNA-response elements. J. Biochem. 2009;146:77–85. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho Y., Gorina S., Pavletich N.P. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265:346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tidow H., Melero R., Fersht A.R. Quaternary structures of tumor suppressor p53 and a specific p53 DNA complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12324–12329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705069104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen Y., Dey R., Chen L. Crystal structure of the p53 core domain bound to a full consensus site as a self-assembled tetramer. Structure. 2010;18:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emamzadah S., Tropia L., Halazonetis T.D. Crystal structure of a multidomain human p53 tetramer bound to the natural CDKN1A (p21) p53-response element. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011;9:1493–1499. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vuzman D., Levy Y. Intrinsically disordered regions as affinity tuners in protein-DNA interactions. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:47–57. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05273j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yao N.Y., Georgescu R.E., O’Donnell M.E. Single-molecule analysis reveals that the lagging strand increases replisome processivity but slows replication fork progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13236–13241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906157106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dunn A.R., Kad N.M., Wallace S.S. Single Qdot-labeled glycosylase molecules use a wedge amino acid to probe for lesions while scanning along DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7487–7498. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cuculis L., Abil Z., Schroeder C.M. Direct observation of TALE protein dynamics reveals a two-state search mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7277. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kad N.M., Wang H., Van Houten B. Collaborative dynamic DNA scanning by nucleotide excision repair proteins investigated by single-molecule imaging of quantum-dot-labeled proteins. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson S.R., Dunn A.R., Wallace S.S. Two glycosylase families diffusively scan DNA using a wedge residue to probe for and identify oxidatively damaged bases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E2091–E2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400386111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veprintsev D.B., Freund S.M., Fersht A.R. Core domain interactions in full-length p53 in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2115–2119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511130103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang F., Rajagopalan S., Fersht A.R. Multiple conformations of full-length p53 detected with single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:20758–20763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909644106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beshnova D.A., Cherstvy A.G., Teif V.B. Regulation of the nucleosome repeat length in vivo by the DNA sequence, protein concentrations and long-range interactions. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sahu G., Wang D., Nagaich A.K. p53 binding to nucleosomal DNA depends on the rotational positioning of DNA response element. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:1321–1332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cui F., Zhurkin V.B. Rotational positioning of nucleosomes facilitates selective binding of p53 to response elements associated with cell cycle arrest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:836–847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schwarz P.M., Hansen J.C. Formation and stability of higher order chromatin structures. Contributions of the histone octamer. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:16284–16289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwarz P.M., Felthauser A., Hansen J.C. Reversible oligonucleosome self-association: dependence on divalent cations and core histone tail domains. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4009–4015. doi: 10.1021/bi9525684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hupp T.R., Lane D.P. Allosteric activation of latent p53 tetramers. Curr. Biol. 1994;4:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang P., Reed M., Tegtmeyer P. p53 domains: structure, oligomerization, and transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:5182–5191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dudenhöffer C., Kurth M., Wiesmüller L. Dissociation of the recombination control and the sequence-specific transactivation function of P53. Oncogene. 1999;18:5773–5784. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kato S., Han S.Y., Ishioka C. Understanding the function-structure and function-mutation relationships of p53 tumor suppressor protein by high-resolution missense mutation analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:8424–8429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1431692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kawaguchi T., Kato S., Ishioka C. The relationship among p53 oligomer formation, structure and transcriptional activity using a comprehensive missense mutation library. Oncogene. 2005;24:6976–6981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaglia G., Guan Y., Lahav G. Activation and control of p53 tetramerization in individual living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15497–15501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311126110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.