Metabolic adaptations of Sherpas to high altitudes

Sherpa mountaineers in the Himalayas. Image courtesy of iStock/fotoVoyager.

Previous studies have suggested that enhanced mechanisms for tissue oxygen delivery in Sherpas of Tibetan descent might play a role in their ability to survive at high altitude. However, whether metabolic adaptations that alter tissue oxygen utilization underlie this ability remains unclear. James Horscroft et al. (pp. 6382–6387) evaluated a group of 10 lowlanders and 15 Sherpas, around 27 years of age, on a research expedition as the participants ascended an altitude of 5,300 m from Kathmandu to Mount Everest Base Camp. The authors measured muscle energetics and metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, and mitochondrial function, among other markers, before and at various times during the ascent. Overall, the authors report, compared with the lowlanders, the Sherpas exhibited enhanced efficiency of oxygen use, reduced capacity for fatty acid oxidation, improved muscle energetics, and increased protection from oxidative stress under low-oxygen conditions at high altitude. The metabolic adaptations were associated with an allele of the PPARA gene—implicated in lipid metabolism—that is enriched in Sherpas, compared with lowlanders. According to the authors, the findings illuminate the metabolic basis of Sherpa adaptation to life at high altitudes and carry implications for understanding human diseases marked by hypoxia. — R.W.

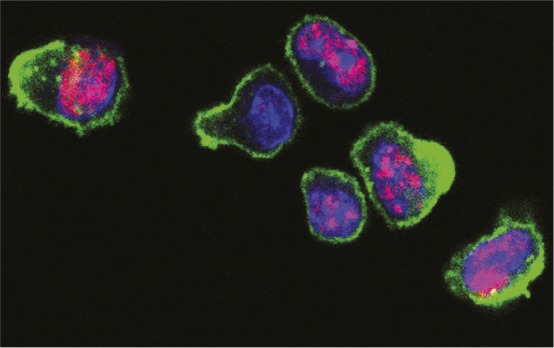

Targeting DNA damage response to treat immune diseases

Confocal image of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells (green), with nucleus (blue) and γH2AX (pink), a marker of DNA damage response.

Immunosuppressive drugs can help treat autoimmune diseases and transplant rejection. Though effective, such drugs typically inhibit broad swaths of the immune system, posing substantial risks to patients. To specifically target undesirable immune responses, Jonathan McNally et al. (pp. E4782–E4791) focused on activated T cells that multiply at exceptionally high rates in response to specific antigens. Hypothesizing that such rapid division of T cells induces DNA damage, the authors examined antigen-activated murine and human T cells in vivo for evidence of DNA damage response. After confirming that antigen activation induces significant DNA breaks, the authors tested a variety of small molecules for their ability to target signaling downstream of DNA damage and selectively kill activated T cells in vitro. Two candidate strategies emerged: inhibiting the MDM2 protein to potentiate the tumor suppressor protein p53, and impairing cell cycle checkpoints by inhibiting the CHK1/2 or WEE1 kinase enzymes. According to the authors, combining these two approaches, dubbed p53 potentiation with checkpoint abrogation, ablates recently activated T cells with minimal toxicity while sparing naive, regulatory, and quiescent immune cells. — T.J.

Fueling the brain during exhaustive exercise

Marathon runners. Image courtesy of Flickr/Julian Mason.

Brain cells called astrocytes store glycogen as an energy source. The breakdown of glycogen gives rise to lactate, which is transported by monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) into neurons. Physical exercise increases the brain’s energy needs, but the role of astrocytic glycogen in the exercising brain remains unclear. Takashi Matsui et al. (pp. 6358–6363) measured glycogen and MCT proteins in the brains and skeletal muscles of rats undergoing prolonged exhaustive exercise on a treadmill. Compared with sedentary rats, the muscles and brains of exhausted rats showed reduced glycogen. In addition, exercise led to an increase in the level of brain MCT2 protein, which transports lactate into neurons, as well as an increase in the level of muscle MCT proteins. Using metabolomics, the authors found that exhausted rats maintained preexercise levels of the energy source ATP in the brain, but not in muscles, through the use of lactate and other glucose-derived and glycogen-derived energy sources. Injecting a glycogen breakdown inhibitor decreased both hippocampal lactate production and hippocampal ATP levels in exhausted animals and lowered endurance capacity. An inhibitor of brain MCT also decreased hippocampal ATP levels and accelerated exhaustion. According to the authors, lactate derived from astrocytic glycogen might play a protective role in the brain during prolonged exhaustive exercise and contribute to endurance capacity. — L.C.

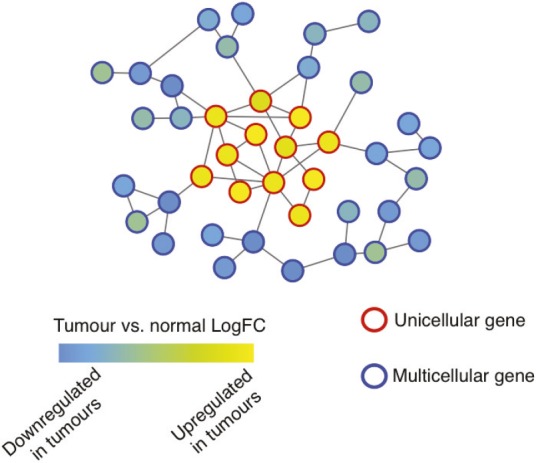

Cancer and partitioning of gene function

Network diagram of expression of unicellular and multicellular genes in cancer.

Cancer cells, regardless of tissue of origin and genetic background, exhibit hallmark features consistent with breakdown in regulatory functions associated with multicellularity. Because they affect highly evolved processes like cell differentiation and extracellular signaling, such abnormalities suggest that tumorigenesis reflects the activation of ancient genes that predate the emergence of multicellular organisms. However, evidence supporting this premise is lacking. Using data from the Cancer Genome Atlas, Anna Trigos et al. (pp. 6406–6411) combined expression analysis with phylogenetic and interaction data to investigate the relationship between changes in gene expression in tumors and the evolutionary histories of those genes for seven types of solid tumors. Gene age and expression level in tumors were closely related, exhibiting patterns in processes central to cancer that implied both a history of selection and active upregulation during malignant transformation. The authors found that highly conserved genes from unicellular organisms are preferentially expressed in tumors at the expense of coordinated function between unicellular and multicellular components of gene regulatory networks. The study points to 12 highly connected genes as potential drivers of tumorigenesis, according to the authors. — T.J.

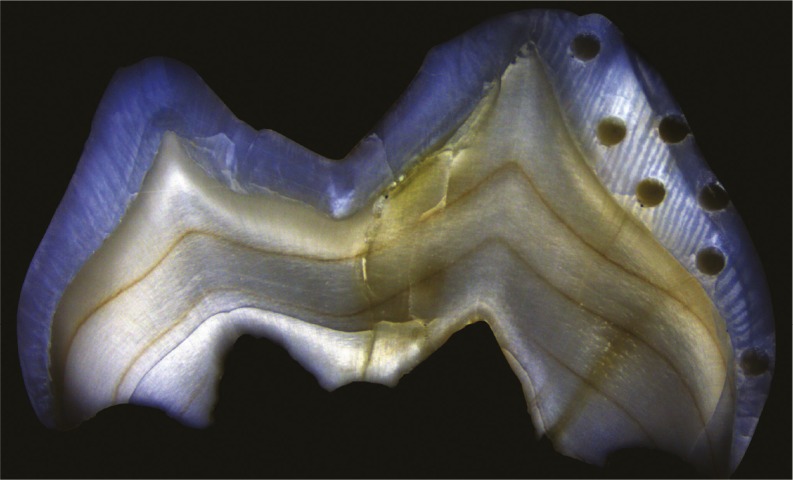

Identifying time of weaning

Human deciduous molar sampled along enamel crown.

Weaning practices can provide insights into the health and demography of present and past human populations. However, the study of prehistoric and historic weaning practices has been hampered by a lack of direct evidence of weaning behavior in archeological and fossil records. To identify biomarkers that would enable the reconstruction of human weaning practices, Théo Tacail et al. (pp. 6268–6273) analyzed stable calcium isotopes (44Ca/ 42Ca) from the enamel of 51 deciduous teeth from 12 modern humans; mammalian breastmilk has low levels of 44Ca compared with the average Western diet. The authors found that the enamel became enriched in 44Ca during the transition from prenatal to postnatal development. During the first 5–10 months of life, the proportion of 44Ca relative to 42Ca increased in tooth enamel for individuals who were either not breastfed or breastfed only for short periods, whereas the calcium isotope ratio did not change over the same period in individuals who were breastfed for more than 12 months. According to the authors, the observed variations in calcium isotope ratios in enamel record a transition from placental nutrition to an adult-like diet, reflect the duration of breastfeeding, and may help glean insights into weaning practices in past hominins. — L.C.