Abstract

Modified mRNA (modRNA) is a new technology in the field of somatic gene transfer that has been used for the delivery of genes into different tissues, including the heart. Our group and others have shown that modRNAs injected into the heart are robustly translated into the encoded protein and can potentially improve outcome in heart injury models. However, the optimal compositions of the modRNA and the reagents necessary to achieve optimal expression in the heart have not been characterized yet. In this study, our aim was to elucidate those parameters by testing different nucleotide modifications, modRNA doses, and transfection reagents both in vitro and in vivo in cardiac cells and tissue. Our results indicate that optimal cardiac delivery of modRNA is with N1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate nucleotide modification and achieved using 0.013 μg modRNA/mm2/500 cardiomyocytes (CMs) transfected with positively charged transfection reagent in vitro and 100 μg/mouse heart (1.6 μg modRNA/μL in 60 μL total) sucrose-citrate buffer in vivo. We have optimized the conditions for cardiac delivery of modRNA in vitro and in vivo. Using the described methods and conditions may allow for successful gene delivery using modRNA in various models of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: delivery, modified mRNA, heart

Modified mRNA is a new technology in the field of somatic gene transfer in the heart. The optimal delivery method of modified mRNA in the heart has not yet been characterized. Sultana et al. indicate the optimal condition for cardiac delivery of modified mRNA.

Introduction

Somatic gene transfer approaches have been used extensively in experimental models, and they may provide a new treatment option for several diseases, including chronic or acute cardiovascular diseases.1, 2, 3 Gene delivery systems can be classified into two main groups: non-viral physio-chemical systems and recombinant viral systems. The advantages of non-viral systems include the ease of vector production, greater expression cassette size, and relatively minimal biosafety risks.4, 5, 6, 7 The limitations include lower transfection efficiency and transient effect due to clearance and degradation of the transfer vector.8 Non-viral vectors include plasmid DNA, mRNA, and polymer/liposome-DNA/mRNA complexes. Compared with DNA plasmids, mRNA has several advantages as a gene delivery tool. One advantage is that mRNA does not require nuclear localization or transcription prior to translation of the gene of interest. An additional advantage is the negligible risk of genomic integration of the delivered sequence.

In the early 1990s, mRNA was successfully delivered into brain and skeletal muscle.9, 10 However, the use of mRNA as a method to transfer genes into mammalian tissue has been very limited since. This is mostly due to mRNA activation of the innate immune response via stimulation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs).11, 12 In addition, mRNA is prone to cleavage by RNase when delivered in vivo.11, 13, 14 Kariko et al.14 showed that modified mRNA (modRNA), produced by the replacement of uridine with pseudouridine, resulted in changes to the mRNA secondary structure that prevented innate immune system recognition and RNase degradation. In addition, the replacement nucleotide, pseudouridine, occurs naturally in the body,15, 16, 17 and it enhanced translation of the modRNA compared to the unmodified version.14, 18 We12, 19, 20, 21 and others22, 23 have shown that modRNA drives transient and robust expression of genes of interest in cardiomyocytes (CMs) in vitro and in the hearts of mice.12, 19, 21, 22 Additionally, published results indicate that modRNA can be delivered into CMs of rat or porcine hearts in vivo.23 In a murine experimental myocardial infarction (MI) model, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A) modRNA delivery, immediately upon the induction of coronary ischemia, markedly improved heart function and enhanced long-term survival of treated animals.12 This improvement was, in part, due to the mobilization of epicardial progenitor cells and re-direction of their differentiation toward other cardiovascular cell types.12

Others have shown that IGF1 modRNA delivery had a cytoprotective effect on CMs in vitro and in vivo.22 Recently, our group showed that IGF1 expression in the myocardium after MI induces the formation of epicardial fat.19 The formation of epicardial fat was reduced using IGF1R dominant-negative modRNA that was applied in a biocompatible gel on the surface of the heart immediately after injury.19 More recent studies have used modRNA in the cardiovascular system. ModRNAs encoding for VEGF-A, IGF1 EGF, HGF, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, SDF-1, FGF-1, GH, SCF, and different reporter genes have been investigated in cardiac cells and tissue.12, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 In these latter studies, the nucleotide modifications used to generate the modRNAs consisted of a 100% replacement of uridine with pseudouridine and cytidine with 5-methylcytidine (ψU + 5mC).12, 19, 20, 23, 24 Over the past few years, several groups have shown that other nucleotide modifications, such as 100% replacement of uridine by 2-Thiouridine-5′-Triphosphate (2-thio ψU)18 or by 1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate (1-mψU),25, 26 yield high modRNA translation efficiency in non-cardiac tissue, with no immunogenicity and resistance to RNase. Early experiments with modRNA have used standard reagents (e.g., RNAiMAX) without systematic optimization of nucleotide composition or gene delivery protocol. In this study, we optimized modRNA composition, concentration, and mode of delivery to achieve maximal efficacy of gene transfer in cardiac cells and in murine myocardium.

Results

We have used cardiac cells and tissues to test different modRNA nucleotide modifications for their immunogenicity, their stability in mouse blood plasma, and translation to protein efficiency. All tested nucleotide modifications of modRNAs had a significantly reduced activation of hallmark innate immunity genes, such as INFα or -β and RIG-1, in comparison to unmodified mRNA (Figure S1A). Additionally, the tested modRNA modifications were more stable, with a higher RNA integrity for a longer time in the presence of mouse blood plasma, compared to unmodified mRNA (Figure S1B). Moreover, all nucleotide modifications yielded higher protein translation compared to unmodified mRNA (Figure 1). Importantly, of all the tested modifications, a complete replacement of uridine with 1-mψU yielded a significantly higher (3.9-fold increase in vitro and 4.5-fold increase in vivo, p < 0.001) modRNA translation in comparison to a modRNA that was previously used in cardiac cells and organs12, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 27 (ψU + 5mC; Figures 1E and 1F). This higher translation efficiency also affected modRNA kinetics in vitro and pharmacokinetics in vivo: 1-mψU modRNA modification prolonged kinetics by 24 hr in vitro and pharmacokinetics by 96 hr in vivo compared to modRNA having ψU + 5mC nucleotide modification (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Optimizing ModRNA Modification to Increase Translation and Expression Kinetics in Vitro and In Vivo

Luc mRNA expression was compared between mRNA with or without nucleotide modifications (unmodified), using the IVIS imaging system, in rat neonatal CMs in vitro or CFW mouse heart in vivo. The nucleotide modifications tested were as follows: 100% replacement of uridine by 2-Thiouridine-5′-Triphosphate (2-thio ψU) or by 1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate (1-mψU) or 100% replacement of uridine by Pseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate and cytidine by 5-Methylcytidine-5′-Triphosphate (ψU + 5mC). (A and B) Representative images of transfected (with RNAiMAX) neonatal CMs or mice. Images were taken 24 hr post-transfection with 2.5 μg/well in a 24-well plate or intramyocardial injection with 100 μg modified or non-modified Luc mRNA, respectively. (C and D) Kinetics or pharmacokinetics of modified or non-modified Luc mRNA in vitro or in vivo, respectively. (E and F) Efficient translation of Luc modRNA with different nucleotide modifications. Total Luc signal was measured over 5 or 10 days post-transfection in vitro or in vivo, respectively. Results represent two independent experiments with n = 2 or n = 3 (total n = 5 wells or mice; ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Using this superior modRNA modification (1-mψU), we evaluated the optimal conditions of modRNA transfection into CMs in vitro (Figure 2). For this, we isolated rat neonatal or human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)-derived CMs and plated them separately onto 24-well plates in sub-confluent conditions. We transfected the different types of CMs with nuclear GFP (nGFP), naked modRNA, or mixed with different commercially available transfection reagents (Figures 2A–2D). We found that positively charged transfection reagents are necessary to achieve a high level of CM transfection. Additionally, we found that naked nGFP modRNA, delivered in sucrose-citrate buffer or saline, yielded very low transfection levels in neonatal rat (1.3% or 0.4%, respectively) and in hPSC-derived CMs (2.1% or 0.5%, respectively). In contrast, the use of positively charged transfection reagents, such as RNAiMAX, resulted in a very high transfection level in neonatal rat (98.3%) and in hPSC-derived CMs (98.9%). The use of other reagents for modRNA transfection, such as TransIT, jetMESSENGER, or MessengerMAX, yielded high transfection levels of neonatal rats (95.3%, 93.4%, or 77.6%, respectively) or hPSC CMs in vitro (94.2%, 90.2%, or 97.3%, respectively). We selected RNAiMAX for further investigation.

Figure 2.

Optimizing Vehicle and ModRNA Dose for CM Transfection In Vitro

Rat neonatal or hPSC-derived CMs were isolated and plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates. Different transfection regents were used to transfect the CMs with 2.5 μg nGFP modRNA (1-mψU)/per well. Then 18 hr post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained for actinin (red) and GFP (green). ImageJ was used to calculate the number of nGFP+ and Actinin+ cells in each well. (A and B) Representative images of transfected rat neonatal CMs (A) or hPSC-derived CMs (B) with RNAiMAX-nGFP modRNA complex 18 hr post-transfection. (C and D) Quantification of transfection efficiency of rat neonatal (C) or hPSC-derived CMs (D) using different transfection reagents. (E and F) Optimal doses per well were tested using optimal transfection reagent (RNAiMAX) using different doses of nGFP in rat neonatal CMs (E) or in hPSC-derived CMs (F). (G–J) FACS analysis was used 18 hr post-transfection with RNAiMAX and different nGFP modRNA doses to measure median GFP intensity and cell death (percentage Annexin V of viable cells) for rat neonatal CMs (G and I) or hPSC-derived CMs (H and J), respectively. Results represent two independent experiments with n = 3 wells (*p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test; scale bar, 10 μm).

We titrated modRNA doses in order to obtain the optimal dose that yields the highest number of transfected cells (GFP+ cells) and GFP intensity with low cell death (Annexin V+ cells). We found that transfection of 2.5 μg/1 × 105 cells/well (sub-confluent condition) in a 24-well plate (0.013 μg/mm2) resulted in >95% GFP+ cells in both types of CMs (Figures 2E–2J). In neonatal rat CMs, 5 or 10 μg per well/105 cells resulted in higher GFP intensity compared to 2.5 μg; however, the percentage of cell death also increased significantly with the higher modRNA doses (p < 0.01). In hPSC CMs, the highest GFP intensity accompanied by low cell death was achieved with 2.5 μg nGFP modRNA transfected into CMs plated in sub-confluent conditions.

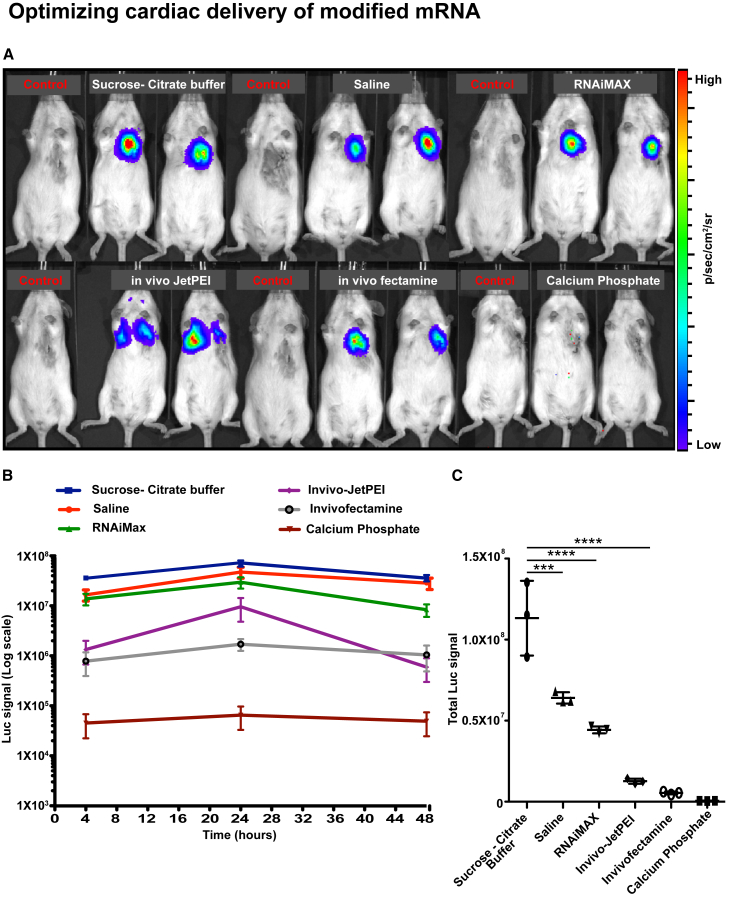

We then tested various modRNA compositions and deliveries in vivo. We developed a mouse model of open-chest surgery that allows direct injection of modRNA into the myocardium (100 μg/heart [1.6 μg modRNA/μL in 60 μL total volume]; Figure S2). Using this model, we directly delivered luciferase (Luc) modRNA into the myocardium with one of the following vehicles/reagents: (1) naked (saline or sucrose-citrate buffer), (2) positively charged particles (such as RNAiMAX or calcium phosphate), or (3) encapsulated in nanoparticles (in vivo fectamine or in vivo jetPEI) (Figure 3). We detected protein expression in the heart post-direct injection into the myocardium using most delivery approaches (Figure 3A; Figure S3A). The use of calcium phosphate resulted in a very low expression in the heart. The use of in vivo jetPEI resulted in modRNA expression in the lung after direct myocardial injection. Luc signal quantifications indicated that naked delivery (sucrose-citrate buffer or saline) increased protein translation by 53- to 226-fold compared to delivery of modRNA encapsulated in nanoparticles (in vivo JetPEI or in vivo fectamine, respectively) (Figures 3B and 3C). The use of RNAiMAX for Luc modRNA yielded a high expression (4.4 × 107 total Luc signal); however, it was associated with increased cell death in the injected area compared to naked Luc modRNA delivery (Figure S3B). Importantly, delivery of Luc modRNA in sucrose-citrate buffer yielded a higher expression of Luc compared to saline (11.3 × 107 versus 6.4 × 107 total Luc signal, respectively) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Vehicle Optimization for ModRNA Cardiac Tissue Transfection In Vivo

Luc modRNA at a dose of 100 μg (1-mψU)/heart, complexed with different commercially available RNA transfection reagents, was injected directly into myocardium of CFW mice in an open-chest surgery. The IVIS imaging system was used to calculate gene expression at different time points (4, 24, and 48 hr). (A) Representative images of transfected mice 24 hr post-injection directly into myocardium with different commercially available RNA transfection reagents. (B and C) Pharmokinetics (B) or efficient translation (C) of Luc modRNA transfected with different RNA transfection reagents and measured at different time points (4, 24, and 48 hr) using IVIS. Results represent three independent experiments with n = 2 or 3 mice (****p < 0.0001 and ***p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

We next sought to optimize the modRNA dose to achieve the highest protein translation and biodistribution in vivo. Delivery of 100 μg/heart of Luc modRNA with sucrose-citrate buffer resulted in the highest expression in vivo compared to delivery of 50 or 200 μg/heart (11.4 × 107 versus 8.95 × 107 or 8.06 × 107 total Luc signal, respectively) (Figures 4A–4C). Notably, injection of a volume of 60 μL (modRNA mix) with different doses of Cre modRNA (50, 100, and 200 μg) directly into the myocardium of Rosa26mTmG mice resulted in a similar biodistribution, covering more than 20% of the left ventricle (Figures 4D and 4E). Lastly, we tested the dynamics of modRNA translation into protein after direct injection into skeletal or cardiac muscles in vivo. For this purpose, mice were injected with luciferin (150 μg/g body weight) and anesthetized prior to Luc modRNA injections into the quadriceps femoris (Figures S4A and S4B) or heart muscles (Figures S4C and S4D). The IVIS system was used to monitor translation every 2–5 min. We detected protein translation that was significantly above baseline reading in the quadriceps femoris or the heart 13 or 10 min post-injection, respectively (Figure S4).

Figure 4.

Optimizing ModRNA Dose for Cardiac Tissue Transfection In Vivo

Different doses (50, 100, and 200 μg) of Luc or Cre modRNA (1-mψU)/heart, delivered in sucrose-citrate buffer, were injected directly into the myocardium of CFW or Rosa26mTmG mice, respectively, in an open-chest surgery. (A) Representative image of transfected CFW mice 24 hr post-intramyocardial injection with different Luc modRNA doses. (B and C) Pharmokinetics (B) or efficient translation (C) of Luc modRNA transfected with different doses and measured at different time points (4, 24, and 48 hr) using IVIS. (D) Representative images of a transfected heart (transfected cells are green and non-transfected cells are red) or heart cross-sections (short axis view) of Rosa26mTmG mouse 24 hr post-injection of 100 μg Cre modRNA directly into myocardium. (E) Quantification of the biodistribution of different doses of Cre modRNA post-transfection in vivo. Results represent two independent experiments with n = 2 or 3 mice (total n = 3–5 mice; **p < 0.01 and *p < 0.05; N.S., not significant; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Discussion

ModRNA is a novel gene transfer platform that allows for efficient, local, fast (in minutes), and transient (a few days in the adult heart) gene delivery that is non-immunogenic and with good biodistribution (>20% of the left ventricle). The platform can be used for the delivery of a single gene or gene combinations in a variety of organs, including the heart.12, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 27, 28 In this work, we describe the optimization of modRNA delivery into cardiac cells and tissue. We found, in line with others,14, 18, 25, 26, 29 that modRNA delivery yields a higher expression with reduced immunogenicty and better resistance to RNase activity when compared to unmodified mRNA delivery (Figure 1; Figure S1). We show that 100% replacement of uridine with 1-mψU results in higher protein translation, in vitro and in vivo, compared to other tested modifications. These findings are aligned with the data from other laboratories25, 26 showing that 1-mψU-incorporated mRNA outperforms ψU-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and after intradermal or intramuscular injections in mice.25

We further show that positively charged transfection reagents are necessary for in vitro modRNA transfection of neonatal rat or hPSC-derived CMs (Figure 2). We hypothesize that the transfection reagent masks the negatively charged mRNA with positively charged polymers or lipids, allowing electromagnetic attachment and endocytosis to the negatively charged cell membrane, while also creating a dense modRNA complex that gravitates toward the cell surface when placed in culture media. When saline or sucrose-citrate buffer are used, a modRNA complex does not form. The result is a significantly reduced transfection efficiency in various types of CMs. Importantly, we show that positively charged transfection reagents, such as RNAiMAX, increase cell death in vitro (Figures 2I and 2J). Therefore, the amount of modRNA that can be transfected per squared millimeter culture dish (contains about 2,500 cells) with different types of CMs is limited. Therefore, we show that the primary CM cell type optimal transfection is 0.013 μg/mm2 and using a higher amount is associated with increased cell death (Figure 2). We have shown, using a mouse model (Figure S2), that naked modRNA (delivered with sucrose-citrate buffer or saline) resulted in significant local protein translation in the heart (Figure 3A; Figure S3A). The local expression may be related to the short half-life of modRNA in the plasma that may limit modRNA travel to different organs away from the site of injection. We now show, for the first time, that naked modRNA delivery with sucrose-citrate buffer or saline yields a higher protein translation compared to encapsulation of modRNA in nanoparticles, such as in vivo fectamine or in vivo jetPEI. These results indicate that the beneficial protective role nanoparticles may have on modRNA hinders its translation into protein. Additionally, our data show that modRNA delivery in a mixture with transfection reagents (RNAiMAX) is detrimental to the heart and may increase apoptosis in cardiac cells in vivo (Figure S3B). Our results strongly support naked modRNA delivery as the optimal approach in direct intramuscular injection (Figures 3B and 3C). Importantly, sucrose-citrate buffer delivery is superior to saline delivery (11.3 × 107 versus 6.4 × 107 total Luc signal), and it yielded more protein translation in vivo (Figure 3C). This may be explained by the fact that sucrose is an available energy source and may generally increase mRNA translation and endocytosis.30, 31, 32 Moreover, sucrose increases the viscosity of the modRNA solution and prevents clumping of single-stranded modRNAs in the mixture, clumping that may result in untranslatable double-stranded modRNA that may also elicit an immune response via Toll-like receptor 3.33 Additionally, citrate, is a chelating agent for mRNA and, thus, may increase its preservation.34

As modRNA delivery to the heart is limited by the amount of volume that can be injected into the mouse myocardium (60 μL/heart), we evaluated the optimal dose of modRNA per microliter for heart delivery. Our results show that 100 μg/heart (1.6 μg/μL) is the optimal dose to achieve the highest translation efficiency (Figure 4A). While the dose-response ratio was kept when 50 or 100 μg was delivered, delivery of 200 μg modRNA resulted in a reduced or similar translation compared to 100 μg (Figure 4B). It is plausible that the high concentration of modRNA (3.2 μg/μL) creates undesired clumping/attachments of single-stranded modRNA, which result in low translation. Notably, no significant differences were found in biodistribution among the different doses of Cre modRNA delivered into heart Rosa26mTmG mice (Figures 4C–4E), and all resulted in ∼20% transfection of the left ventricle. Our unpublished data indicate that, in rats, a minimum of 20% transduction of left ventricle is required to alter cardiac function in vivo. Our results indicate that modRNA is widely translated in the myocardium, beyond the needle track, and that the level of protein translation is dependent on the modRNA dose. From our studies and experience, we can attempt to extrapolate our results and calculate the doses necessary for human heart transduction. While a mouse heart weighs 0.18 g,35 the normal human heart weighs at least 300 g36 (1,667-fold difference). If the modRNA dose ratio is kept, the optimal dose in human would be 166.7 mg. This is a very large dose that may be cost prohibitive. Clearly more research is needed to improve modRNA translation (via new modifications, modRNA capping, or 5′ UTRs) and transfection (possibly via the use of improved reagents) in order to move the field toward a clinical RNA therapy phase in humans. Finally, we have shown that modRNA delivery into skeletal or cardiac muscle tissues resulted in rapid protein translation at about 10 min post-delivery. This uniquely rapid pharmacokinetics strengthens the potential use of the modRNA gene delivery method in conditions of acute cardiac disease, such as MI.

In conclusion, we have shown that modRNA modification using 1-mψU yields superior protein translation in cardiac cells and tissues. The delivery of 0.013 μg modRNA/mm2 mixed with positively charged transfection reagent is optimized for in vitro transfection into two types of CMs. Furthermore, the delivery of 1.6 μg/μL (60 μL/100 μg per heart) in sucrose-citrate buffer is optimized for in vivo transfection into the mouse heart (see summary in Figure 5). This work sheds light on the conditions needed for improved cardiac delivery of modRNA in vitro and in vivo, and it may promote modRNA delivery use and accessibility in cardiac studies for both basic and translational science.

Figure 5.

Optimized Cardiac Delivery of ModRNA

Cardiac delivery of modRNA with 100% replacement of uridine with 1-mψU yields the highest gene expression and longest pharmacokinetics in comparison to other nucleotide modifications, both in vitro and in vivo. CM transfection in vitro (rat neonatal or hPSC) is optimal with a positively charged transfection reagent, such as RNAiMAX, TransIT, jetMESSENGER, or MessengerMAX, in a concentration of 0.013 μg modRNA/1 mm2 well diameter. For in vivo cardiac delivery in mice, our data show that 100 μg/heart (1.6 μg modRNA/μL in 60 μL total) in sucrose-citrate buffer directly injected into myocardium yields the highest gene expression and covers close to a quarter of the left ventricle of mouse heart.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animal procedures were performed under protocols approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Care and Use Committee. CFW or R26mTmG mice strains, male and female, were used. Luc or Cre modRNAs (50, 100, and 200 μg/heart, as mentioned in the text) were injected directly into the quadriceps femoris muscle or into the myocardium in an open-chest surgery (see Figure S2 for more details).

Synthesis of ModRNA

ModRNAs were transcribed in vitro from plasmid templates (sequences provided in previous publications12, 19, 21), using a custom ribonucleoside blend of Anti Reverse Cap Analog, 3′-O-Me-m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G (6 mM, TriLink Biotechnologies), guanosine triphosphate (1.5 mM, Life Technologies), adenosine triphosphate (7.5 mM, Life Technologies), cytidine triphosphate (7.5 mM, Life Technologies), or 5-methylcytidine triphosphate (7.5 mM, TriLink Biotechnologies) and uridine triphosphate (7.5 mM, Life Technologies), or pseudouridine triphosphate, or 2-Thiouridine-5′-Triphosphate, or N1-Methylpseudouridine-5′-Triphosphate (7.5 mM, TriLink Biotechnologies), as described previously.12, 19 The mRNA was purified using a Megaclear kit (Life Technologies) and was treated with Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs); then it was purified again using the Megaclear kit. The mRNA was quantitated by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific), precipitated with ethanol and ammonium acetate, and resuspended in 10 mM TrisHCl and 1 mM EDTA. For a detailed protocol please see our recent publication.21

In Vitro Transfection

Different doses of Luc or nGFP mRNA with different nucleotide modifications were transfected into neonatal rat or hPSC-derived CMs using the following different transfection reagents: RNAiMAX or MessengerMAX (Life Technologies), TransIT (Mirus Bio), jetMessenger or JetPEI or Interferin (Polyplus), Dharmacon (GE Healthcare), X-tremeGENE (Roche), or naked with sucrose-citrate buffer. The sucrose-citrate buffer contains 20 μL sucrose in nuclease-free water (0.3 g/mL) and 20 μL citrate (0.1 M, pH 7; Sigma) mixed with 20 μL modRNA at different concentrations in saline or only in saline (modRNA at different concentrations in 60 μL saline). The transfection mixture was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then it was added to cells cultured in basal medium containing growth factors and 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza). Then, 18 hr post-transfection, cells were fixed, stained, and evaluated using florescence microscopy or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

In Vivo Transfection

Different doses of Luc or Cre modRNA or mRNA with different nucleotide modifications in a total volume of 60 μL were delivered via direct injection to the myocardium in an open-chest surgery (see Figure S2). The modRNA was formulated with different transfection reagents according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. The transfection reagents used were in vivo JetPEI (Polyplus), invivofectamine 3.0, RNAiMAX (Life Technologies), or Calcium Phosphate (Sigma); naked modRNA with sucrose-citrate buffer; and saline (see above [In Vitro Transfection] for details). The transfection mixture was made according to the manufacturer’s protocol and was directly injected (two to three individual injections, 20 μl each) into the quadriceps femoris muscle or heart muscle.

Detection of Luciferase Expression Using the IVIS System

Different doses of Luc mRNA with different nucleotide modifications were transfected into CMs in vitro or directly injected into the quadriceps femoris muscle or the heart of CFW mice. Bioluminescence imaging of the transfected cells or injected mice was taken at different time points (4–240 hr). Each unit of Luc signal represents p/s/cm2/sr × 106. To visualize tissues expressing Luc in vivo, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories), and luciferin (150 μg/g body weight; Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally. Mice were imaged using an IVIS100 charge-coupled device imaging system every 2 min until the Luc signal reached a plateau. Imaging data were analyzed and quantified with Living Image software. Cells or muscle tissues that were transfected with saline or RNAiMAX served as a baseline reading for Luc expression. To account for Luc background signal, the signal from untransfected mice (yields ∼1 × 104 Luc signal) was subtracted from the reads of transfected mice.

hPSC Differentiation

The hPSCs (H9) were differentiated along a cardiac lineage as previously described.37 Briefly, hPSCs were maintained in E8 media and passaged every 4–5 days onto matrigel-coated plates. To generate embryonic bodies (EBs), hPSCs were treated with 1 mg/ml collagenase B (Roche) for 30 min or until cells dissociated from plates. Cells were collected and centrifuged at 1,300 rpm for 3 min, and they were resuspended into small clusters of 50–100 cells by gentle pipetting in differentiation media containing RPMI (Gibco), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 4 × 104 monothioglycerol (MTG, Sigma), 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma), and 150 μg/mL transferrin (Roche). Differentiation media were supplemented with 2 ng/mL BMP4 and 3 μmol Thiazovivin (Millipore) (day 0). EBs were maintained in six-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning) at 37°C in 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2. On day 1, media were changed to differentiation media supplemented with 20 ng/mL BMP4 (R&D Systems) and 20 ng/mL Activin A (R&D Systems). On day 4, media were changed to differentiation media supplemented with 5 ng/mL VEGF (R&D Systems) and 5 μmol/L XAV (Stemgent). After day 8, media were changed every 5 days to differentiation media without supplements.

Neonatal Rat CM Isolation

CMs from 3- to 4-day-old neonatal rat heart were isolated as previously described.22 Neonatal rat ventricular CMs were isolated from 3- to 4-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). We used multiple rounds of digestion with 0.14 mg/mL collagenase II (Invitrogen). After each digestion, the supernatant was collected in horse serum (Invitrogen). Total cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants were discarded and cells were resuspended in DMEM (Gibco) with 0.1 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma), 0.5% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (100×), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cells were plated in plastic culture dishes for 90 min until most of the non-myocytes attached to the dish and myocytes remained in the suspension. Myocytes were then seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate. Neonatal rat CMs were incubated for 48 hr in DMEM containing 5% horse serum. After incubation, cells were transfected with Luc or nGFP modRNAs as described above.

Real-Time qPCR Analyses

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time qPCR analyses were performed on a Mastercycler realplex 4 Sequence Detector (Eppendoff) using SYBR Green (QuantitectTM SYBR Green PCR Kit, QIAGEN). Data were normalized to Gapdh expression where appropriate (endogenous controls). Fold changes in gene expression were determined by the ∂∂CT method and were presented relative to an internal control. PCR primer sequences were as follows: for INFα, forward primer ATGGCTAGRCTCTGTGCTTTCCT and reverse primer AGGGCTCTCCAGAYTTCTGCTCTG; for INFβ, forward primer AAGAGTTACACTGCCTTTGCCATC and reverse primer CACTGTCTGCTGGTGGAGTTCATC; and for RIG-1, forward primer GGACGTGGCAAAACAAATCAG and reverse primer GCAATGTCAATGCCTTCATCA.

RNA Integrity Test in Plasma

Plasma of CFW mice was isolated as described before.38 Plasma was immediately frozen and kept at −80°C. On the day of the experiment, diluted plasma (1:50 in PBS) was warmed to 37°C. Then 10 μL modRNA or mRNA (0.25 μg/μL) with different nucleotide modifications was added at a 1:1 ratio to the diluted plasma and kept at 37°C for 15 min. Samples were collected at different time points (1, 3, 10, and 15 min) and snap frozen before sending for an RNA integrity test using the bioanalyzer in the Genomics Core Facility in Icahn Mount Sinai Medical School.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed on cryosections of hearts fixed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained using primary antibodies for GFP, TUNEL, or Actinin (all from Abcam). Secondary antibodies were used for fluorescent labeling of the cells (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Cells and heart slides were imaged using a Zeiss Slide Scanner Axio Scan. Quantification of immunostaining in cardiac sections was performed using ImageJ software.

Statistical Analyses

Values are reported as mean ± SEM or in dot plot graphs (with median and quartiles indicated). Comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

Author Contributions

N.S. designed and carried out most of the experiments, analyzed most of the data, and wrote the manuscript. A.M. designed and performed in vitro transfection in CM experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.H. performed and analyzed the TUNEL expression experiment. J.K. prepared modRNA for this study. N.S. and E.Y. carried out in vitro CM isolation and cell culture experiments. D.C. prepared the hPSC-derived CMs used in this study. E.C. performed all mouse open-chest surgery and intramyocardial injection of modRNA. N.D. prepared the hPSC-derived CMs used in this study and analyzed data. R.J.H. designed experiments, analyzed data, and revised the manuscript. L.Z. designed and carried out experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Talha and Irsa Mehmood for their help with this manuscript. This work was funded by a cardiology start-up grant for the Zangi lab; by NIH R01 HL117505, HL 119046, HL129814, 128072, HL131404, HL135093, and P50 HL112324; and by a Transatlantic Fondation Leducq grant.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.016.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.del Monte F., Hajjar R.J. Efficient viral gene transfer to rodent hearts in vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003;219:179–193. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-350-x:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Monte F., Ishikawa K., Hajjar R.J. Gene Transfer to Rodent Hearts In Vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1521:195–204. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6588-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ylä-Herttuala S., Bridges C., Katz M.G., Korpisalo P. Angiogenic gene therapy in cardiovascular diseases: dream or vision? Eur. Heart J. 2017:ehw547. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrieu-Soler C., Bejjani R.A., de Bizemont T., Normand N., BenEzra D., Behar-Cohen F. Ocular gene therapy: a review of nonviral strategies. Mol. Vis. 2006;12:1334–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaanine A.H., Kalman J., Hajjar R.J. Cardiac gene therapy. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010;22:127–139. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felgner P.L. Nonviral strategies for gene therapy. Sci. Am. 1997;276:102–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0697-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahle J., Walther W. Vectors and strategies for nonviral cancer gene therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2016;16:443–461. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2016.1134480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelfelder S., Lee M.K., deLima-Hahn E., Wilmes T., Kaul F., Müller O., Kleinschmidt J.A., Trepel M. Vectors selected from adeno-associated viral display peptide libraries for leukemia cell-targeted cytotoxic gene therapy. Exp. Hematol. 2007;35:1766–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jirikowski G.F., Sanna P.P., Maciejewski-Lenoir D., Bloom F.E. Reversal of diabetes insipidus in Brattleboro rats: intrahypothalamic injection of vasopressin mRNA. Science. 1992;255:996–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1546298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff J.A., Malone R.W., Williams P., Chong W., Acsadi G., Jani A., Felgner P.L. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science. 1990;247:1465–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIvor R.S. Therapeutic delivery of mRNA: the medium is the message. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:822–823. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zangi L., Lui K.O., von Gise A., Ma Q., Ebina W., Ptaszek L.M., Später D., Xu H., Tabebordbar M., Gorbatov R. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells and induces vascular regeneration after myocardial infarction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karikó K., Buckstein M., Ni H., Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karikó K., Muramatsu H., Welsh F.A., Ludwig J., Kato H., Akira S., Weissman D. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1833–1840. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas J., Engels J.W. A convenient approach towards 2′-O-modified RNA-oligonucleotides on solid support using universal nucleosides. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2008;52:331–332. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limbach P.A., Crain P.F., Pomerantz S.C., McCloskey J.A. Structures of posttranscriptionally modified nucleosides from RNA. Biochimie. 1995;77:135–138. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)88116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardi N., Muramatsu H., Weissman D., Karikó K. In vitro transcription of long RNA containing modified nucleosides. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;969:29–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-260-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kormann M.S., Hasenpusch G., Aneja M.K., Nica G., Flemmer A.W., Herber-Jonat S., Huppmann M., Mays L.E., Illenyi M., Schams A. Expression of therapeutic proteins after delivery of chemically modified mRNA in mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:154–157. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zangi L., Oliveira M.S., Ye L.Y., Ma Q., Sultana N., Hadas Y., Chepurko E., Später D., Zhou B., Chew W.L. Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Receptor-Dependent Pathway Drives Epicardial Adipose Tissue Formation After Myocardial Injury. Circulation. 2017;135:59–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lui K.O., Zangi L., Silva E.A., Bu L., Sahara M., Li R.A., Mooney D.J., Chien K.R. Driving vascular endothelial cell fate of human multipotent Isl1+ heart progenitors with VEGF modified mRNA. Cell Res. 2013;23:1172–1186. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondrat J., Sultana N., Zangi L. Synthesis of Modified mRNA for Myocardial Delivery. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1521:127–138. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6588-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang C.L., Leblond A.L., Turner E.C., Kumar A.H., Martin K., Whelan D., O’Sullivan D.M., Caplice N.M. Synthetic chemically modified mrna-based delivery of cytoprotective factor promotes early cardiomyocyte survival post-acute myocardial infarction. Mol. Pharm. 2015;12:991–996. doi: 10.1021/mp5006239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turnbull I.C., Eltoukhy A.A., Fish K.M., Nonnenmacher M., Ishikawa K., Chen J., Hajjar R.J., Anderson D.G., Costa K.D. Myocardial Delivery of Lipidoid Nanoparticle Carrying modRNA Induces Rapid and Transient Expression. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:66–75. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G., McCain M.L., Yang L., He A., Pasqualini F.S., Agarwal A., Yuan H., Jiang D., Zhang D., Zangi L. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat. Med. 2014;20:616–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andries O., Mc Cafferty S., De Smedt S.C., Weiss R., Sanders N.N., Kitada T. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J. Control. Release. 2015;217:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardi N., Tuyishime S., Muramatsu H., Kariko K., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Madden T.D., Hope M.J., Weissman D. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J. Control. Release. 2015;217:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lui K.O., Zangi L., Chien K.R. Cardiovascular regenerative therapeutics via synthetic paracrine factor modified mRNA. Stem Cell Res. (Amst.) 2014;13(3 Pt B):693–704. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chien K.R., Zangi L., Lui K.O. Synthetic chemically modified mRNA (modRNA): toward a new technology platform for cardiovascular biology and medicine. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014;5:a014035. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boros G., Miko E., Muramatsu H., Weissman D., Emri E., Rózsa D., Nagy G., Juhász A., Juhász I., van der Horst G. Transfection of pseudouridine-modified mRNA encoding CPD-photolyase leads to repair of DNA damage in human keratinocytes: a new approach with future therapeutic potential. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2013;129:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Etxeberria E., Baroja-Fernandez E., Muñoz F.J., Pozueta-Romero J. Sucrose-inducible endocytosis as a mechanism for nutrient uptake in heterotrophic plant cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:474–481. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamm M., Peviani A., Honsel A., Snel B., Smeekens S., Hanson J. Increased sucrose levels mediate selective mRNA translation in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:306. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0306-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicolaï M., Roncato M.A., Canoy A.S., Rouquié D., Sarda X., Freyssinet G., Robaglia C. Large-scale analysis of mRNA translation states during sucrose starvation in arabidopsis cells identifies cell proliferation and chromatin structure as targets of translational control. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:663–673. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexopoulou L., Holt A.C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R.A. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koff M.D., Plaut K. Expression of transforming growth factor-alpha-like messenger ribonucleic acid transcripts in the bovine mammary gland. J. Dairy Sci. 1995;78:1903–1908. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(95)76815-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoit B.D., Ball N., Walsh R.A. Invasive hemodynamics and force-frequency relationships in open- versus closed-chest mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:H2528–H2533. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paulsen S., Vetner M., Hagerup L.M. Relationship between heart weight and the cross sectional area of the coronary ostia. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. [A] 1975;83:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1975.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L., Soonpaa M.H., Adler E.D., Roepke T.K., Kattman S.J., Kennedy M., Henckaerts E., Bonham K., Abbott G.W., Linden R.M. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen S.D., Mikkelsen L.F., Fels J.J., Bodvarsdóttir T.B., Hansen A.K. Quality of plasma sampled by different methods for multiple blood sampling in mice. Lab. Anim. 2009;43:65–71. doi: 10.1258/la.2008.007075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.