Abstract

Objective

Depressive symptoms frequently co-exist in adolescents with alcohol use and peer violence. This paper’s purpose was to examine the secondary effects of a brief alcohol-and-violence-focused ED intervention on depressive symptoms.

Method

Adolescents (ages 14–18) presenting to an ED for any reason, reporting past year alcohol use and aggression, were enrolled in a randomized control trial (control, therapist-delivered brief intervention [TBI], or computer-delivered brief intervention [CBI]). Depressive symptoms were measured at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months using a modified 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10). Poisson regression was used (adjusting for baseline age, gender, and depressive symptoms) to compare depressive symptoms at follow-up.

Results

Among 659 participants, higher baseline depressive symptoms, female gender, and age >16 were associated with higher depressive symptoms over time. At 3 months, CBI and TBI groups had significantly lower CESD-10 scores than the control group; at 6 months, intervention and control groups did not differ; at 12 months, only CBI had a significantly lower CESD-10 score than control.

Conclusions

A single-session brief ED-based intervention focused on alcohol use and violence also reduces depressive symptoms among at-risk youth. Findings also point to the potential efficacy of using technology in future depression interventions.

Keywords: Adolescent, Depression, Brief Intervention, Emergency Department

1. INTRODUCTION

Depression is common among adolescents and emerging adults, with significant short- and long-term effects.(1, 2) Adolescence is a vulnerable time for both depression and other health risks, including substance use and violence.(3, 4) A robust, multi-directional relationship between depression, violence, and substance use has been observed, likely due to similar underlying developmental and contextual considerations.(5–7) Certain maladaptive developmental features of adolescence, such as impulsiveness and deficits in emotional regulation, increase risk of both depression and related health risks.(5) Adolescents with these characteristics also often lack access to preventive resources and opportunities.(3, 8–10)

Adolescents seen in the emergency department (ED) are more likely than the average American teen to report past-year physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and alcohol and other drugs use(3, 11–13) and are less likely to have a medical home or access to treatment and prevention services.(14, 15) Although multi-session therapeutic interventions effectively decrease depressive symptoms and associated risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, violence) among at-risk youth,(16) these treatments are generally not accessible or feasible for these youth.(9, 17) The ED therefore represents a unique opportunity to reach youth with limited social, material, and institutional resources.(18, 19)

Adolescent peer violence, alcohol and other drug use, and depression symptoms derive from similar deficits in emotional regulation, problem-solving skills, and self-efficacy.(20–22) Prior literature has shown that SafERteens, a brief intervention delivered to youth endorsing alcohol and violence history, had positive impacts on violence victimization, aggression, and alcohol consequences.(23, 24) It is theoretically possible that a single-session, motivational interviewing-based, violence and alcohol focused brief intervention might also affect depression symptoms, given the mutual skill deficits underlying both symptom complexes. Little is known, however, regarding the impact of such brief, single-session interventions on comorbid issues such as depression symptoms. This manuscript examines secondary effects of the SafERteens intervention on participants’ depressive symptoms.(23, 24)

2. METHODS

Methods for the SafERteens randomized control trial (RCT) have previously been reported.(23, 24) Adolescents (age: 14–18) presenting to a Level 1 ED in Flint, MI for any reason were systematically recruited for the study. Recruitment proceeded seven days a week from 9/2006–9/2009. Exclusion criteria included ED presentation for acute sexual assault or suicidal ideation, or a physical or mental inability to provide assent/consent. After consent (or assent with parental consent if age <18), research assistants (RAs) screened participants using a brief computerized questionnaire. Adolescents reporting any past-year physical peer aggression (e.g., fighting, measured using a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale-2(25)) and past-year alcohol use (defined as drinking alcohol >2–3 times in the prior year, measured using items from the National Study of Adolescent Health(26)) were eligible for the larger RCT testing the brief intervention. Institutional review board approval was obtained from University of Michigan and Hurley Medical Center, and a National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality for human subjects was obtained.

Eligible adolescents who completed written consent (or assent and parental consent, if age<18) then self-administered a computerized baseline survey [see Measures below] and were randomized to one of three study conditions: Therapist brief intervention (TBI); Computer-delivered brief intervention (CBI); or, enhanced usual care (EUC). Computerized follow-up assessments were self-administered at 3-, 6-, and 12-months after the ED visit. Participant remuneration was a $1 gift (e.g., gum) for the screening survey; $20 for the baseline assessment; and $25, $30, and $35 for the 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups, respectively.

2.1 Measures

Socio-demographic measures (age, race, ethnicity, gender, receipt of public assistance, and education status) and mental health service usage were assessed using items from the National Study of Adolescent Health.(27) For analytic purposes, age was collapsed into the indicator of ≥16; race and ethnicity were collapsed into African-American and other.

Depressive symptoms were measured using a modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10).(4, 28) The Cronbach’s α for the scale within our population was 0.85. The total depression score was the sum of the scores for eight (negative valence) items plus the reverse scores for two (positive valence) items. No other mental health disorders were assessed.

Although violence and alcohol use were measured in the study, these measures were not included in this analysis as they did not differ between groups at baseline and have been extensively described elsewhere.

2.2 Study Conditions

2.2.a: Brief Intervention Content

The 30–45 minute SafERteens brief intervention (BI) was delivered to participants in the intervention arms using two parallel delivery modalities (therapist [TBI], computer [CBI]) within the ED prior to hospital discharge or admission. The TBI was delivered by a research social worker therapist, aided by a tablet computer to standardize structure and delivery of intervention content. The CBI was delivered entirely by a computer program, with audio interaction with virtual “friends.” Delivery of both TBI and CBI were paused and restarted as necessary to avoid interfering with medical care.

Both BIs were based on motivational interviewing (MI), with a primary focus on alcohol and peer violence(29, 30) and were designed to cover parallel content, with delivery mechanisms resulting in some differences. Sections included: goals/values, normative statistics for drinking/fighting, reasons to avoid drinking and fighting, role-play scenarios based on the participant’s risk behaviors, and next steps. Thus, although not specifically focused on depression, the intervention addressed potentially related risk factors for alcohol use and aggression (e.g., peer and family influences, motivations for drinking such as stress/coping and enhancement, anger management/conflict resolution, and avoiding community violence). The intervention included a review of resources to address depression, such as in the summary segment, in which the intervention prompted interest in obtaining counseling services, and provided community resource lists.

Family members and visitors were asked to leave the treatment room prior to delivery of the BI, to maintain participant privacy and confidentiality.

2.2.b: Enhanced Usual Care

Participants randomized to the EUC condition received a brochure of available community resources addressing substance use, violence, and mental health issues.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary Park, NC). Descriptive statistics (means/SD for continuous variables and proportions/confidence intervals for categorical variables) were calculated. Poisson regression was used, in light of the non-normality of the outcome variable and the multiple outcome measures, to examine depressive symptoms among the CBI, TBI, and EUC conditions. Separate models were fit for each time point. Analyses included all available cases with CESD-10 scores at baseline and the corresponding follow-up data point. Randomization strata (gender and age group) as well as baseline depressive symptoms were controlled for; in accordance with standard recommendations for analysis of RCTs, potential confounders that were equally distributed at baseline, such as race and usage of mental health resources, were not included in the model (31). The level of overdispersion in the Poisson models was estimated using the ratio of the Pearson χ2 to the degrees of freedom.(32) As necessary, we adjusted our inference for overdispersion by scaling all χ2 statistics by the estimated dispersion parameter(32) and scaling the standard errors by its square root. Over-dispersion was observed in all models with an estimated dispersion parameter of 2.38, 2.51, and 2.45, in the 3-, 6-, and 12-month models, respectively.

3. RESULTS

As reported previously,(23, 24) 726 (87.6% of eligible) adolescents enrolled in the study. Those refusing enrollment were less likely to be African-American (p=0.004) and female (p=0.02) compared with those eligible and enrolling. The CESD-10 measure was not administered to the first 67 participants; the total baseline analytic sample was therefore 659.

The analytic sample was 43% male (n=285), 57% African-American (n=377), and 57% reporting receipt of public assistance (n=376). The mean age of participants was 16.8 years (SD=1.3). Mean baseline CESD-10 score was 13.2 (SD=6.6). As described elsewhere, there were no significant differences in demographics, violence exposure, drinking behavior, or depressive symptoms among the three groups (CBI, TBI, or EUC).(23, 24) See Table 1 for demographics details.

TABLE 1.

BASELINE DEMOGRAPHICS (N=659)

| TOTAL n=659 | Computer N=207 | Therapist N=226 | Control N=226 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 374 (56.8%) | 118 (57.0%) | 129 (57.1%) | 127 (56.2%) |

| Age ≥ 16 | 531(80.6%) | 162 (78.3%) | 188 (83.2%) | 181 (80.1%) |

| Poor academic performance | 438 (66.5%) | 129 (62.3%) | 149 (65.9%) | 160 (70.8%) |

| African American | 377 (57.2%) | 116 (56.0%) | 132 (58.4%) | 129 (57.1%) |

| Receipt of public assistance | 376 (57.3%) | 122 (59.5%) | 133 (59.1%) | 121 (53.5%) |

| Past-year binge drinking | 340 (51.6%) | 100 (48.3%) | 118 (52.2%) | 122 (54.0%) |

| Past-year weapon carriage | 313 (47.5%) | 105 (50.7%) | 106 (46.9%) | 102 (45.1%) |

| Community violence exposure (Mean, SD) | 4.3 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.4(3.1) | 4.3(3.0) |

| CESD-10 (Mean, SD) | 13.2(6.6) | 13.0 (6.6) | 13.6 (6.8) | 13.0 (6.5) |

White participants were less likely than participants of other races to complete the 3-month follow-up; otherwise, baseline characteristics (i.e., age, gender, depressive symptoms) were not significantly related to follow-up completion. The follow-up rate among the analytic sample (those who completed the baseline CESD-10) at 3-, 6-, and 12-months was 82.7% (n=545), 85.6% (n=564), and 81.5% (n=537), respectively.

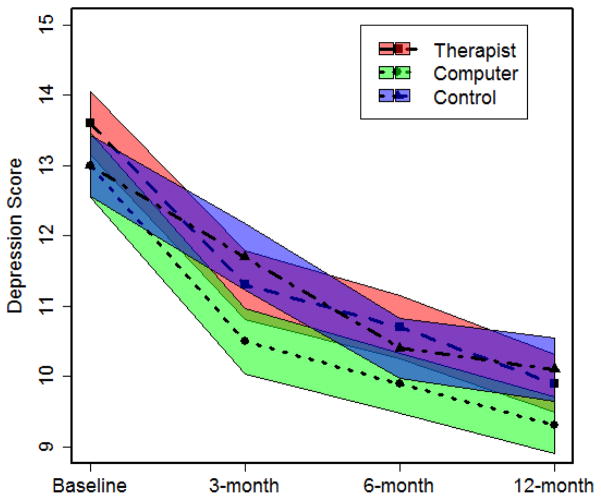

At each follow-up time point, a decrease in CESD-10 score was observed in all three groups compared with baseline (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Self-report of depressive symptoms (CESD-10 score)* over time, by intervention group

* width of shaded region = 95% CI

Table 2.

Self-report of depressive symptoms over time (CESD-10 Score)

| Baseline Mean (SD) | 3-month Mean (SD) | 6-month Mean (SD) | 12-month Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist | 13.6 (6.8) | 11.3 (6.8) | 10.7 (6.2) | 9.9 (5.5) |

| Computer | 13.0 (6.6) | 10.5 (6.0) | 9.9 (5.7) | 9.3 (5.3) |

| Control | 13.0 (6.5) | 11.7 (6.5) | 10.4 (6.0) | 10.1 (6.2) |

There was no significant difference in use of mental health services between groups at 3-, 6-, or 12-month follow-up (20% of CBI, 28.4% of TBI, and 25.4% of EUC participants at 3-months, p=0.13 between groups; 20.6%, 23.4%, and 21.6%, respectively, at 6-months, p=0.77 between groups; and 25.6%, 27.4%, and 24%, respectively, at 12-months, p=0.74 between groups).

In the Poisson regression models (see Table 3), adjusting for baseline age and gender, at 3-month follow-up both CBI and TBI groups had significant decreases in CESD-10 scores compared with the EUC group (p<0.01 and p<0.05 respectively). At 6-month follow-up, CBI and TBI groups did not significantly differ from the control group in CESD-10 score. At 12-month follow-up, a significant effect was observed for the CBI group, which had lower CESD-10 scores than the EUC group (p<0.05), but not for the TBI group. Higher baseline depressive symptoms, female gender, and age >16 were associated with higher depressive symptoms at all time points.

Table 3.

Intervention effect on depressive symptoms (CESD-10 score) at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up: Adjusted Poisson regression [adjusted for gender and age]

| 3-month follow-up (n=545) IRR (95% CI) |

6-month follow-up (n=564) IRR (95% CI) |

12-month follow-up (n=537) IRR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CESD-10 score | 1.05 (1.04– 1.05)*** | 1.04 (1.03– 1.04)*** | 1.03 (1.03– 1.04)*** |

| Computer BI | 0.87 (0.82– 0.91)** | 0.94 (0.88– 1.00) | 0.91 (0.84– 0.96)* |

| Therapist BI | 0.93 (0.87– 0.97)* | 1.01 (0.93– 1.06) | 0.96 (0.90– 1.03) |

| Female | 1.08 (1.02– 1.14)** | 1.06 (1.01– 1.12)* | 1.08 (1.02– 1.14)** |

| Age ≥ 16 | 1.10 (1.03– 1.17)** | 1.10 (1.03– 1.18)** | 1.15 (1.07– 1.23)*** |

Note: Data is bolded if significant, with asterisks indicating the test-statistic:

= p<0.05,

= p<0.01

= p<0.001

IRR: incident rate ratio CI: confidence interval

4. DISCUSSION

These findings support and extend prior work showing that brief, ED-based motivational interventions have demonstrated effectiveness among at-risk youth.(16, 24) In this secondary analysis, an alcohol-and-violence focused brief intervention delivered over 30–45 minutes during the course of a single ED visit also decreased depressive symptoms at 3 month follow-up. This finding is novel, in that prior ED-based BIs focused primarily on reducing risky behaviors, such as alcohol and drug use. Although others have studied the efficacy of “brief” depression interventions in primary care, most of these studies were conducted with adults, and none were single-session interventions.(33). To our knowledge, this analysis therefore represents the first instance in which a brief, ED-based intervention had an effect on psychological symptoms.

The intervention may have reduced depressive symptoms as a byproduct of reduced involvement with violence and alcohol use, which are known to have inter-related underlying mechanisms. Others’ work in adults suggests that targeting both risk behaviors and underlying psychological illness is more effective than focusing on simply addiction or mental illness.(34, 35) Our prior work showed that the TBI and CBI reduced alcohol-related consequences (at 3 and 6 month follow-up) and dating violence (at 3, 6, and 12 months), whereas only the TBI arm reduced peer violence. (at 3, 6, and 12 months) (23, 24, 36) Future work, with a larger sample size, should examine the directionality of the intervention effect, or potential mediation pathways for the observed decrease in depressive symptoms.

The BI did not appear to have influenced depressive symptoms by providing a linkage and referral to services. Rates of mental health service usage were similar among all three groups at all time points, supporting others’ work that a simple BI does not impact linkage to care.(37) This finding may reflect disparities in access to healthcare among socio-economically disadvantaged youth.(9)

Although both intervention delivery formats reduced depressive symptoms at 3-month follow-up, only the computerized intervention had an effect at 12 months. This finding may reflect greater content standardization of the CBI related to coping with negative affect. Although we found no statistically significant effect of the BI at 6 months, inspection of the CI and effect (IRR) suggest that the plausible range of values from the sample data are similar at 6 and 12 months, and the effect generally decreases between 3 and 12 month follow ups. In addition, we found no effect of the TBI at 6- or 12-months. The decrease in effect over time may reflect the dissipation of a one-time intervention’s effect over time.

Future work should elucidate which specific intervention components reduce depressive symptoms among at-risk youth. For example, it may be that technology is particularly relevant for addressing depression among adolescents with multiple risk behaviors. A recent pilot suggests that a BI plus text messages may reduce depressive symptoms among depressed youth with violence involvement.(38) Advantages of technology use for depression prevention include decreased stigma, greater availability, and possibly greater relatability.(39)

Finally, our work supports prior literature on risk factors for depressive symptoms. In particular, it shows a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms at all time points among females and among older adolescents(1, 40); this historical association is supported by our analysis. Our analysis also supports others’ findings that baseline depressive symptoms are the most significant predictor of follow-up depressive symptoms among this at-risk population. More intensive or longitudinal interventions for adolescents with higher levels of depressive symptoms may be needed.

4.1 Limitations

Although data presented in this paper provide a novel contribution to the literature, the analysis was post hoc and was not powered to measure changes in depressive symptoms. Additionally, we did not conduct diagnostic interviews, nor did we assess other mental disorders; it is therefore possible that the measured symptoms represent post-traumatic stress, anxiety, or substance-induced depressive symptoms rather than a major depression diagnosis. Finally, the participants in this study, although representative of the general ED population at this site, may not be representative of adolescents nationwide. Future research should investigate the complexity of depression symptoms, substance use, and violence among youth residing in other socioeconomically disadvantaged communities to replicate these findings.

4.2 Conclusions

Given the paucity of research on the secondary effects of brief interventions for violence and substance abuse on depression symptoms, our findings provide important data to inform early interventions for depression among youth. Data from this study may also provide clues to potential mechanisms of change. Future research is needed to examine whether brief interventions’ effect could be potentiated by increasing focus on negative affect, extending interventions post-discharge, and/or enhancing linkages to community resources. Our findings support additional investigation of brief technology-based interventions to reduce depressive symptoms among at-risk adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Grants: This study was conducted with support by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers AA014889, MH095866].

We would like to thank Linping Duan for her assistance with analysis, and Hannah Kimmel for her assistance with editing. We would like to acknowledge the support of the staff and patients of Hurley Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher JM. Adolescent depression and educational attainment: results using sibling fixed effects. Health Economics. 2010;19:855–871. doi: 10.1002/hec.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranney ML, Walton M, Whiteside L, et al. Correlates of depressive symptoms among at-risk youth presenting to the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl R. Environmental Influences on Biobehavioral Processes. National Academies; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, et al. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanner JL, Arnett JJ. Approaching young adult health and medicine from a developmental perspective. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 2013;24:485–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2324–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmedani BK, Stewart C, Simon GE, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in health care visits made before suicide attempt across the United States. Med Care. 2015;53:430–435. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham RM, Murray R, Walton MA, et al. Prevalence of past year assault among inner-city emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:814–823. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkinson K, Newbury-Birch D, Phillipson A, et al. Prevalence of alcohol related attendance at an inner city emergency department and its impact: a dual prospective and retrospective cohort study. Emerg Med J. 2016;33:187–193. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2014-204581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency departments. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:55–61. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grupp-Phelan J, Delgado SV, Kelleher KJ. Failure of psychiatric referrals from the pediatric emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dicola LA, Gaydos LM, Druss BG, et al. Health insurance and treatment of adolescents with co-occurring major depression and substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham R, Knox L, Fein J, et al. Before and after the trauma bay: The prevention of violent injury among youth. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anixt JS, Copeland-Linder N, Haynie D, et al. Burden of unmet mental health needs in assault-injured youths presenting to the emergency department. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali B, Seitz-Brown CJ, Daughters SB. The interacting effect of depressive symptoms, gender, and distress tolerance on substance use problems among residential treatment-seeking substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;148:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busso DS, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA. Psychosom Med. 2016. Dimensions of Adversity, Physiological Reactivity, and Externalizing Psychopathology in Adolescence: Deprivation and Threat. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan CJ, Andersen SL. Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham RM, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, et al. Brief motivational interviewing intervention for peer violence and alcohol use in teens: one-year follow-up. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1083–1090. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. J Marriage Fam. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris K, Florey F, Tabor J, et al. [Accessed Jan 12, 2017];The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design [WWW document] Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 27.Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. [Accessed Jan 12, 2017];The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design [online] Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html.

- 28.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Resnicow K, Rollnick S. Handbook of Motivational Counseling: Goal-based Approaches to Assessment and Intervention with Addiction and Other Problems. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. Motivational Interviewing in Health Promotion and Behavioral Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, et al. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [Accessed Jan 12, 2017];Annotated SAS Output: Poisson Regression. Available at: http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/sas/output/sas_poisson_output.htm.

- 33.Cape J, Whittington C, Buszewicz M, et al. Brief psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in primary care: meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMC Med. 2010;8:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrissey JP, Jackson EW, Ellis AR, et al. Twelve-month outcomes of trauma-informed interventions for women with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1213–1222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Burnam MA, et al. Review of treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:913–926. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham RM, Whiteside LK, Chermack ST, et al. Dating violence: outcomes following a brief motivational interviewing intervention among at-risk adolescents in an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:562–569. doi: 10.1111/acem.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D, et al. An intervention trial to improve adherence to community treatment by adolescents after a suicide attempt. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranney ML, Freeman JR, Connell G, et al. A Depression Prevention Intervention for Adolescents in the Emergency Department. J Adolesc Health. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Cunningham RM, et al. Acceptability, language, and structure of text message-based behavioral interventions for high-risk adolescent females: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]