Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal muscle disease caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, resulting in a complete loss of the dystrophin protein. Dystrophin is a critical component of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC), which links laminin in the extracellular matrix to the actin cytoskeleton within myofibers and provides resistance to shear stresses during muscle activity. Loss of dystrophin in DMD patients results in a fragile sarcolemma prone to contraction-induced muscle damage. The α7β1 integrin is a laminin receptor protein complex in skeletal and cardiac muscle and a major modifier of disease progression in DMD. In a muscle cell-based screen for α7 integrin transcriptional enhancers, we identified a small molecule, SU9516, that promoted increased α7β1 integrin expression. Here we show that SU9516 leads to increased α7B integrin in murine C2C12 and human DMD patient myogenic cell lines. Oral administration of SU9516 in the mdx mouse model of DMD increased α7β1 integrin in skeletal muscle, ameliorated pathology, and improved muscle function. We show that these improvements are mediated through SU9516 inhibitory actions on the p65-NF-κB pro-inflammatory and Ste20-related proline alanine rich kinase (SPAK)/OSR1 signaling pathways. This study identifies a first in-class α7 integrin-enhancing small-molecule compound with potential for the treatment of DMD.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, α7β1, small molecule therapy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a fatal muscle disease with no cure. Using a muscle cell-based assay, Burkin and colleagues identified SU9516 as an α7 integrin-enhancing small molecule with novel mechanisms of action. They show that a mouse model of DMD treated with SU9516 exhibits reduced pathology and improved muscle strength.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a common form of muscular dystrophy affecting 1 in every 5,000 males.1 It is caused by mutations in the DMD gene, resulting in complete loss of the dystrophin protein.2, 3, 4 In healthy muscle, dystrophin stabilizes the dystrophin glycoprotein complex (DGC), which links laminin in the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the actin cytoskeleton.5, 6 The absence of dystrophin in skeletal muscle leads to significant sarcolemmal tearing and myofiber damage because the levels of compensating structural proteins are inadequate to withstand normal contractile forces.7 The progressive muscle damage and subsequent rounds of degeneration/regeneration are accompanied by elevated levels of inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis. Until recently, glucocorticoids and corticosteroids, prednisone and deflazacort, were the only palliative treatments available for DMD.8, 9, 10 Although current clinical practice guidelines recommend corticosteroid therapy for all DMD patients starting at an early ambulatory stage,11, 12 there are several side effects associated with sustained use. These include stunted growth, obesity, cataracts, and propensity to skeletal fractures.13, 14 In September 2016, an exon-skipping phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO), Exondys 51 (eteplirsen), was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with amenable mutations in exon 51 of DMD.15 Exondys 51 skips its target exon 51, thereby restoring the dystrophin reading frame in these patients. One of the limitations of this drug is that it is applicable to only 13% of DMD patients because it is mutation-specific.15 Current therapeutic approaches under investigation, such as gene replacement and stem cell therapies, seek to treat all patients irrespective of their dystrophin mutation.16, 17, 18 Another strategy that has near-term therapeutic promise is the enhancement of structural proteins like utrophin and α7β1 integrin that compensate for the loss of dystrophin. Transgenic enhancement of these proteins has been demonstrated to significantly rescue the disease phenotype in mouse models of DMD.19, 20, 21

The α7β1 integrin protein is the predominant laminin-binding integrin in skeletal, cardiac, and vascular smooth muscle.22 It is normally distributed along the sarcolemma at costameres and is elevated at neuromuscular and myotendinous junctions in skeletal muscle.23, 24 The α7β1 integrin has structural and signaling functions that contribute to muscle development and physiology and was originally identified as a marker for muscle differentiation.25 Loss of the α7 integrin in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice leads to a severe dystrophic phenotype, and mice do not survive past 4 weeks of age.26 Conversely, transgenic overexpression of the α7β1 integrin ameliorates disease pathology and extends the longevity of severely dystrophic mice.20 Mechanisms that contribute to α7 integrin-mediated rescue of dystrophin-deficient muscle include maintenance of myotendinous and neuromuscular junctions, enhanced muscle hypertrophy and regeneration, and decreased apoptosis and cardiomyopathy.21, 27, 28, 29 Recent evidence suggests that prednisone may maintain function in the golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) dog model by stabilizing α7 integrin protein levels.30 Together, these observations support the idea that the α7β1 integrin is a major disease modifier in DMD and a target for drug-based therapeutics.

Here we report the discovery and preclinical assessment of a first in-class α7 integrin-enhancing small molecule called SU9516. We show that SU9516 treatment in human patient cell lines and mdx mice increases levels of the α7β1 integrin protein complex. This effect possibly occurs through inhibition of the Ste20-related proline alanine rich kinase (SPAK)/OSR1 pathway and downregulation of p65 nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway activation. Most importantly, treatment with SU9516 led to improved muscle function and reduced dystrophic pathology in the mdx mouse model of DMD. Therefore, we believe that SU9516 represents a novel small molecule that has translational potential for the treatment of DMD.

Results

SU9516 Enhances α7 Integrin Levels through Inhibition of the SPAK/OSR1 Kinase Pathway

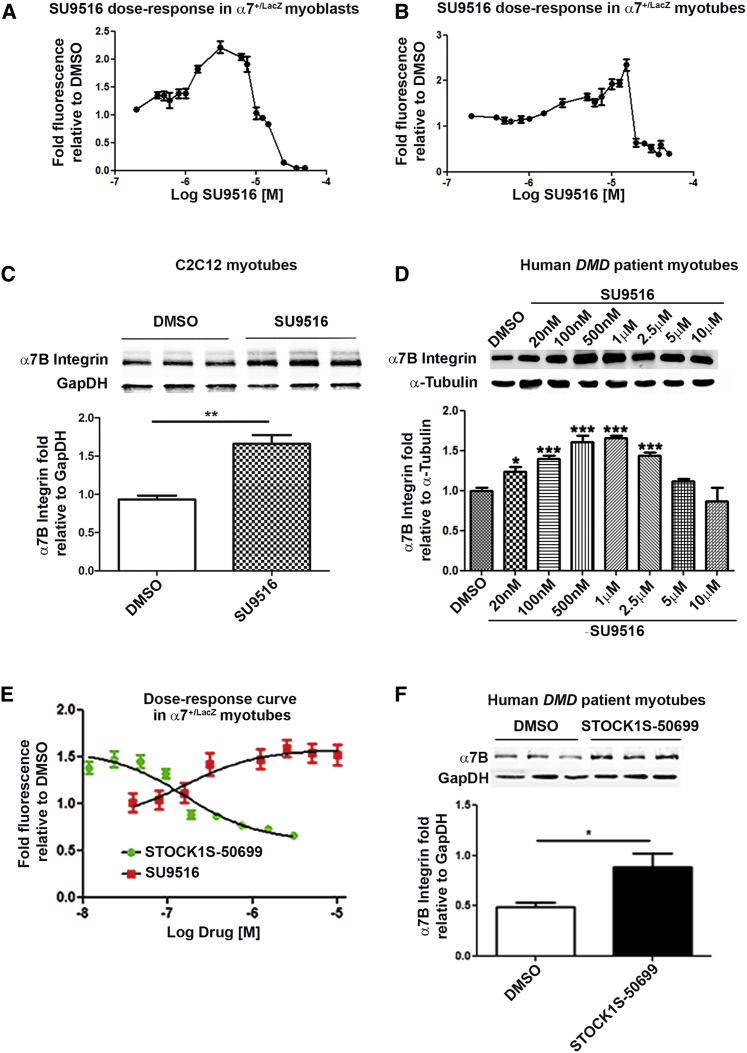

Using a muscle cell-based assay described previously,31 we screened the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC) library and identified SU9516, a compound described in the literature as a selective CDK2 inhibitor.32 SU9516 dose-response curves for α7+/lacZ myoblasts (Figure 1A) and α7+/lacZ myotubes (Figure 1B) were generated for treatments ranging from 0.5–40 μM with a maximal calculated increase (∼3-fold increase) within the established effective therapeutic range.21 The dose-response curves are also represented in a linear scale in Figures S1A and S1B. The maximum effective concentration varied between myoblasts (∼5 μM) and myotubes (∼12 μM), likely because of a reduction in proliferation observed in myoblasts (data not shown). The α7B integrin protein-enhancing effects of SU9516 were initially verified in C2C12 myotubes (Figure 1C) and subsequently in human DMD patient myotubes over a range of concentrations (Figure 1D). The maximum effective concentration was ∼1 μM in human DMD myotubes, with a statistically significant elevation of α7B integrin protein levels at a concentration of 20 nM. Together, these data demonstrate that SU9516 treatment of human and mouse myogenic cell lineages leads to increased α7 integrin protein.

Figure 1.

SU9516 Increases α7 Integrin in Myogenic Cell Lines through Inhibition of the SPAK/OSR1 Pathway

(A and B) SU9516 shows an increase in β-galactosidase activity in (A) α7+/lacZ myoblasts and (B) α7+/lacZ myotubes over a wide range of concentrations. (C and D) Western blot analysis confirmed that treatment with 12 μM SU9516 increased the levels of α7B integrin after 48 hr in (C) C2C12 myotubes (n = 3, Cohen’s d = 4.75) and (D) telomerized human DMD patient myotubes over a wide range of concentrations (n = 3/concentration [conc.], η2 = 0.82). (E) STOCK1S-50699 showed an increase in β-galactosidase activity and obtained maximum fold fluorescence levels, nearly as high as SU9516 in α7+/lacZ-treated myotubes (n = 10/conc.). (F) Western blot analysis in patient human DMD myotubes treated with STOCK1S-50699 showed a 1.8-fold increase in α7B integrin levels (n = 3, Cohen’s d = 2.39). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

We previously tested eight CDK inhibitors (Table S1) with different selectivity and did not see an increase in α7 integrin in myotubes. Therefore, we believe that the increase in α7 integrin mediated by SU9516 is not related to CDK activity. To better determine the specific kinase-inhibitory profile of SU9516 in human DMD patient myotubes, we performed a KiNativ profile assay. Human DMD patient myotubes were treated for 48 hr with 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM SU9516, and then cell lysates were subjected to a KiNativ in situ profiling assay to identify kinase targets (Table S2). The purpose of the KiNativ assay was to elucidate the mechanism of action of SU9516; namely, a specific kinase target that potentially regulates α7 integrin. Based on results depicted in Figure 1D, we observed that, in human DMD myotubes, significant increases in α7B integrin protein levels were seen at concentrations above 20 nM. The maximum effective concentration (maximum increase in α7B integrin) was ∼1 μM in human DMD myotubes. To narrow down the kinases that were inhibited by SU9516 within the effective dose range of 100 nM to 1 μM in human DMD myotubes, we normalized the three concentrations against the “non-effective” dose of 0.01 μM (10 nM). All kinases that were inhibited at this concentration or lower were eliminated as possible candidates for the mechanism of action of SU9516.

The KiNativ data confirmed that SU9516 inhibited CDK2, 4, and 5 by >60% inhibition at 1 μM. In addition, two kinases were inhibited across all concentrations of SU9516; namely, the STE20/SPS1-related proline-alanine-rich protein kinase (STK39/STLK3/SPAK) and the SPAK homolog oxidative stress response 1 (OSR1) kinase. These kinases were inhibited ∼80% at the lowest concentration of 0.1 μM SU9516 (Table S2). To further test whether inhibition of SPAK/OSR1 kinases increased α7 integrin, utilizing α7+/lacZ myotubes, we generated a dose-response curve for a potent suppressor of SPAK/OSR1 activity, designated STOCK1S-50699 (Figure 1E). The linear dose-response curve for STOCK1S-50699 is depicted in Figure S1C. STOCK1S-50699 is a conserved C-terminal (conserved carboxyl-terminal [CCT]) domain inhibitor, a domain that is present on SPAK/OSR1 kinases. Analysis of the dose curve for STOCK1S-50699 in myogenic cells showed an increase in α7 integrin expression levels nearing the maximum fold increase attained by SU9516, although STOCK1S-50699 exhibited toxicity in myotubes at higher concentrations (Figure 1E). Additionally, a western blot analysis utilizing STOCK1S-50699 at a concentration as low as 25 nM in human DMD myotubes showed an increase in the levels of α7B integrin (Figure 1F). Together, these data suggest that SU9516 inhibits the SPAK/OSR1 kinase activity in myogenic cells, which leads to elevated α7 integrin in skeletal muscle.

SU9516 Promotes Myogenic Differentiation

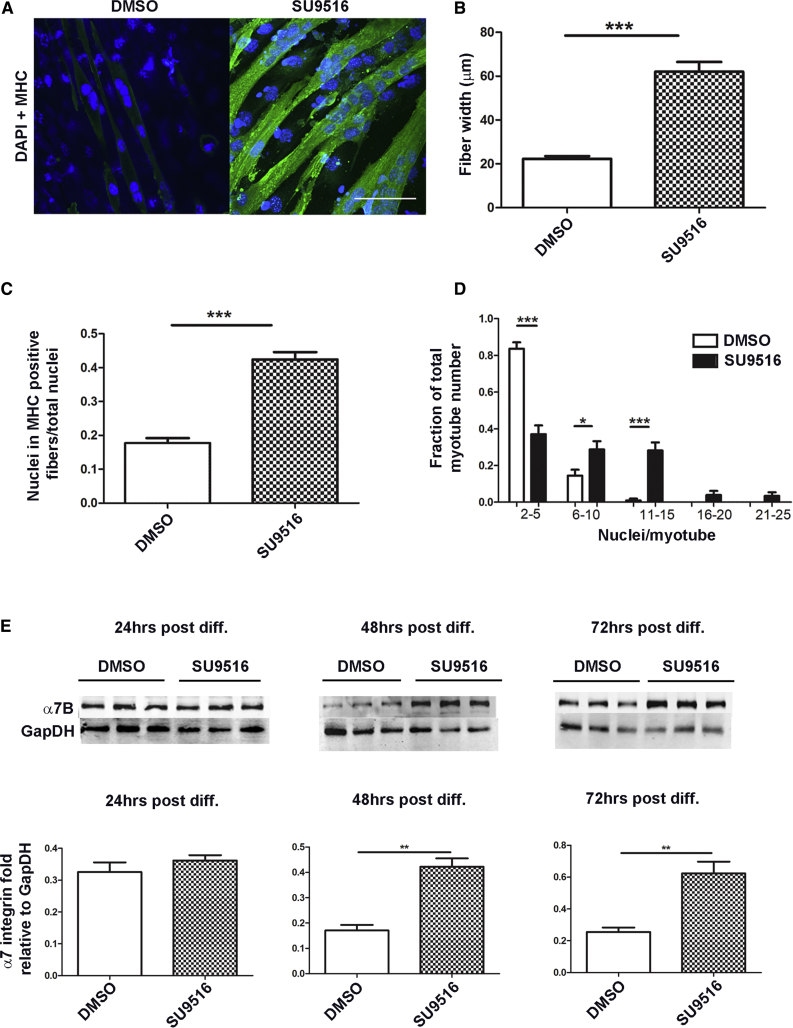

Myoblasts treated with SU9516 exhibited significant morphological changes, and differentiation of myogenic cells was promoted irrespective of serum concentrations. To determine whether SU9516 treatment promoted myogenic fusion/differentiation rates, C2C12 cells were allowed to differentiate in the presence of 12 μM SU9516 or DMSO alone. 72 hr after differentiation, SU9516-treated myotubes were larger and contained more nuclei than DMSO-treated controls. Myofiber size was quantified by measuring the average myofiber width, which increased ∼3-fold in SU9516-treated cells over DMSO (Figures 2A and 2B). The fusion index was also increased ∼3-fold in SU9516-treated myoblasts (Figure 2C), with a shift toward myotubes containing more nuclei per myotube relative to DMSO-treated controls (Figure 2D). We evaluated α7B integrin as a marker of muscle differentiation through the course of differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts. Western blot assays showed that SU9516 treatment upregulated α7B integrin by ∼2.5-fold over DMSO as early as 48 hr after initiation of differentiation (Figure 2E). Together, these results support SU9516 as a mediator of myogenic fusion and differentiation, which makes it a candidate drug for the treatment of dystrophies with impaired myogenic regeneration programs.

Figure 2.

SU9516 Expediates Differentiation in C2C12 Myoblasts

C2C12 myoblasts were differentiated with 12 μM SU9516 or DMSO. After 72 hr, C2C12 myoblasts (cells were treated in three different chamber slides) were fixed and immunostained for MHC. (A) Myofibers stained at 72 hr (green, MHC; blue, DAPI). Magnification, 40×. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) At 72 hr, myotube diameters were increased with SU9516 treatment versus DMSO (n = 45–47 myofibers counted per group). (C) SU9516-treated myogenic cells showed a greater fusion index, defined as the ratio of the number of nuclei in MHC-positive myotubes to the total number of nuclei in one field for five random microscopic fields (n = 35 myofibers evaluated per group). (D) SU9516 treatment increased the fraction of total myotubes with higher numbers of nuclei (n = 35 myofibers evaluated per group). The results represent means and SEM for myofibers treated and evaluated in three different chamber slides. (E) SU9516-treated C2C12 cells showed an early increase in α7B integrin with differentiation versus DMSO (n = 3 per time point, Cohen’s d < 0.8 at 24 hr, d = 5.15 at 48 hr, d = 3.78 at 72 hr). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

Pharmacokinetic Profile of SU9516 in Dystrophic Mice

The uptake and metabolism of SU9516 delivered by oral gavage was investigated to better define the optimal dose selection for initiating preclinical studies in mdx mice. For pharmacokinetic (PK) studies, CD1 mice were treated via oral gavage with a single dose of 10 mg/kg. The intestines, muscle, and serum (n = 3) were assayed at various time points over the next 24 hr for SU9516. The serum half-life, t1/2, was determined to be 1.03 hr (Figure S2A). The 10 mg/kg SU9516 dose appears to be near the maximum tolerated dose because the CD1 mice used in the study showed torpidity up to 24 hr post-treatment. Elevated levels of SU9516 were observed in the intestine and plasma (Figure S2B), whereas only low transient levels were observed in muscle (Figure S2C). The poor distribution in muscle might be attributed to a low volume of distribution or enhanced secretion. A second dosing study was then performed with SU9516 in C57BL10 mice to determine the long-term tolerated dose and test α7 integrin-enhancing activity. Daily treatments of vehicle, 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg doses of SU9516 were administered via oral gavage for 4 days. After 3 days, dosing of the 10 mg/kg/day group was stopped because of increasingly obvious mouse distress. Because the 5 mg/kg/day SU9516 dose appeared to be well tolerated, with no obvious changes in mouse behavior, it was chosen for preclinical pharmacodynamic studies in the mdx mouse model.

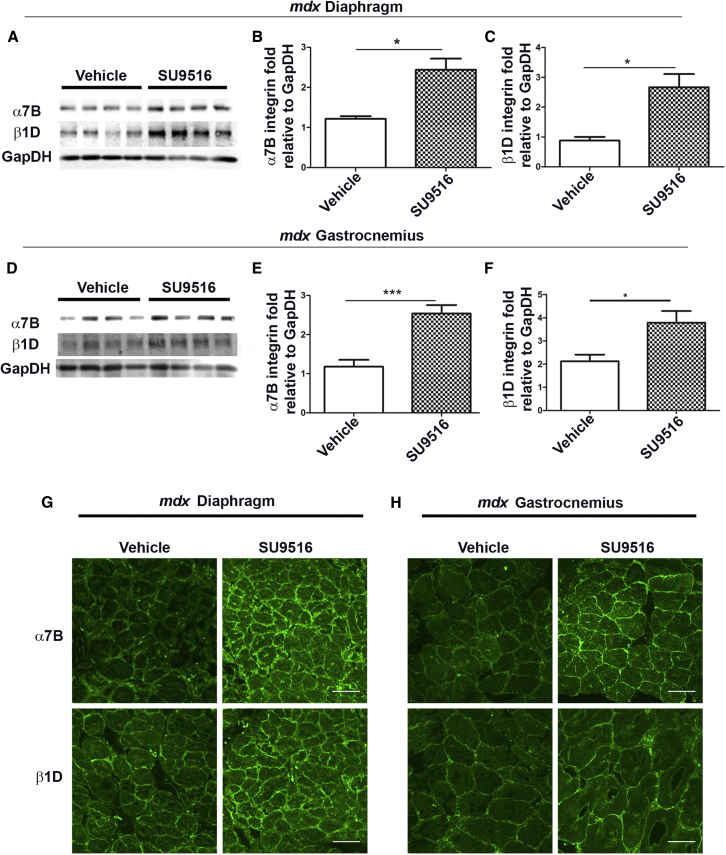

SU9516 Promotes an Increase in α7B and β1D Integrin in mdx Skeletal Muscle

To determine whether SU9516 exhibited on-target in vivo activity, female mdx mice were treated from 3–10 weeks of age with either 5 mg/kg/day of SU9516 or vehicle (2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclo-dextrin). During the course of treatment, none of the experimental mice showed adverse reactions to this dose of SU9516. At 10 weeks of age, diaphragm and gastrocnemius tissues were harvested to quantify α7B and β1D integrin protein levels. A 2.0- and 2.9-fold increase was observed for α7B and β1D integrin, respectively, in the diaphragm muscle of SU9516 treated mdx mice relative to vehicle-treated controls (Figures 3A–3C). The gastrocnemius showed a similar 2-fold increase in α7B integrin but a lower 1.7-fold increase in β1D integrin levels with SU9516 treatments compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figures 3D–3F). Immunofluorescence analysis displayed normal sarcolemmal localization of both α7B and β1D integrin in both the diaphragm and the gastrocnemius muscles of all mice (Figures 3G and 3H). Together, these data show that daily oral treatment of SU9516 increased α7β1 integrin to therapeutic levels in the skeletal muscle of mdx mice.

Figure 3.

SU9516 Increases α7β1 Integrin Levels in the Skeletal Muscle of mdx Mice

(A–C) Western blot analysis performed in the diaphragm and the gastrocnemius muscle of 10-week-old mdx mice showed (A) an increase in the levels of α7B and β1D integrin in the diaphragm of the SU9516-treated mdx mice. This increase is quantified in (B), where an ∼2-fold increase in α7B (n = 4, Cohen’s d = 3.04) and (C) an ∼3.4-fold increase in β1D were observed in the diaphragm of SU9516-treated mdx mice (n = 4, Cohen’s d = 2.74). (D) Western blot analysis in the gastrocnemius showed an increase in the levels of α7B and β1D integrin in SU9516-treated mdx mice. (E and F) These increases were quantified in (E), where an ∼2-fold increase in α7B (n = 6, Cohen’s d = 2.80) and (F) an ∼1.7-fold increase in β1D (n = 4, Cohen’s d = 2.03) were observed in SU9516-treated mdx mice. (G and H) Immunofluorescence performed on 10-μm cryosections for α7B and β1D integrin in (G) the diaphragm and (H) the gastrocnemius muscle of mdx mice showed sarcolemmal localization. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

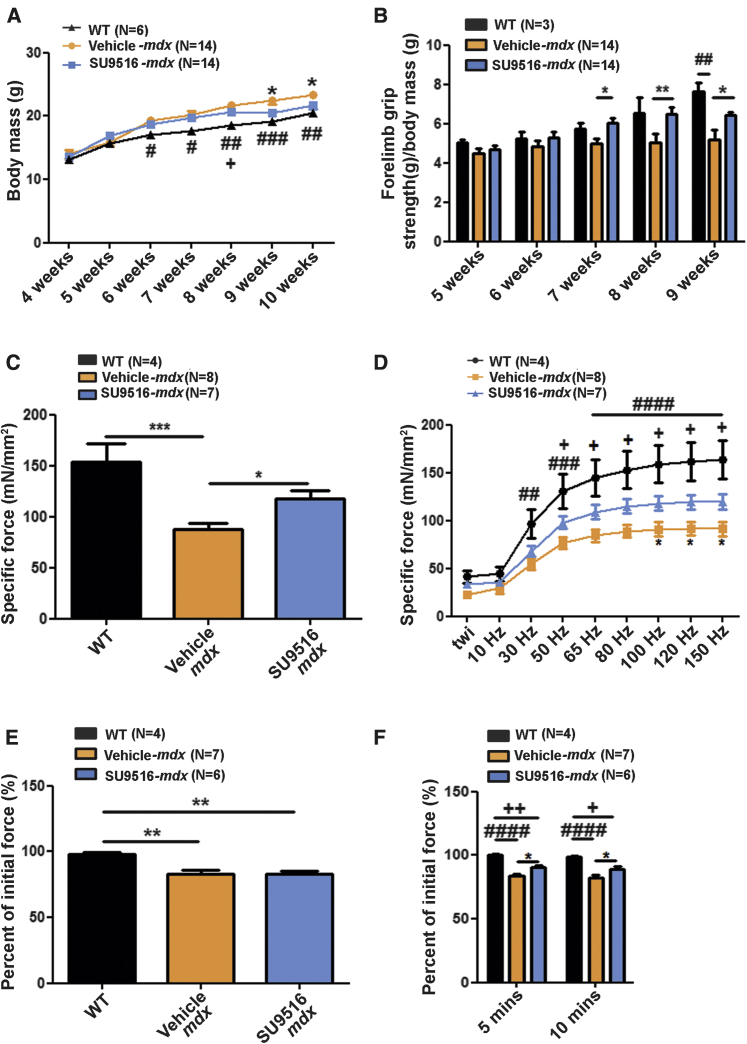

SU9516 Treatment Improves In Vivo Outcome Measures and Muscle Function in mdx Mice

To assess SU9516 safety and efficacy, several parameters, including body mass and forelimb grip strength, were measured. After ∼5 weeks of preclinical treatments, the SU9516-treated mdx mice displayed decreased body mass gain with a progressive shift toward wild-type (WT) body weight compared with vehicle-treated controls and were significantly different from vehicle-treated animals at 9 and 10 weeks of age (Figure 4A). Similarly, normalized average forelimb grip strength indicated that SU9516-treated mdx mice had progressive improvements in muscle function compared with vehicle-treated animals, with significant improvements at 8 and 9 weeks of age (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

SU9516 Improves In Vivo Outcome Measures and Diaphragm Muscle Function in mdx Mice

All comparisons were made across WT, vehicle-treated mdx and SU9516-treated mdx mice. (A) SU9516-treated mice showed a smaller gain in body mass compared with vehicle-treated controls in weeks 9 and 10. WT animals showed the least increase in body weight over time (η2treatment = 0.07). (B) Weekly forelimb grip strength. SU9516 treated mdx mice showed greater muscle strength compared with vehicle-treated mdx mice at weeks 8 and 9 (η2treatment = 0.13). (C) At 10 weeks of age, mouse diaphragm muscle function was assessed. At a 100-Hz tetanic stimulus, SU9516-treated mdx mice showed greater isometric tetanic tension compared with vehicle-treated controls (η2 = 0.59). (D) A force-frequency protocol to measure tetanic tension generated by the diaphragm showed that SU9516-treated diaphragms produced higher tension compared with vehicle-treated diaphragms when stimulated between 100- to 150-Hz frequencies (η2treatment = 0.19). (E) Mdx diaphragms in both SU9516- and vehicle-treated groups fatigued to ∼80% of the initial force (η2 = 0.57). (F) SU9516 diaphragms recovered by ∼8% compared with vehicle (η2treatment = 0.66) 10 min after recovery from fatigue. Tukey post hoc test annotations: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.01 for SU9516-mdx versus Vehicle-mdx treated mdx mice. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001. #### p < 0.0001 vehicle-mdx versus WT. +p < 0.05, ++p < 0.01 for WT versus SU9516-mdx mice. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

We next asked whether treatment with the integrin-enhancing drug SU9516 restores the force deficit seen in the diaphragm of mdx mice33 by measuring the maximum isometric force produced by isolated diaphragm strips (2–4 mm in width). Measurements of in vitro active force developed by diaphragm muscle strips from WT mice, vehicle-treated mdx mice, and SU9516-treated mdx mice were performed in independent experiments. The results revealed that diaphragm muscles from SU9516-treated mice had a higher developed tetanic force (118.1 ± 7.914 mN/mm2) compared with vehicle-treated mice (87.5 ± 6.106 mN/mm2) (Figure 4C). The diaphragm muscles of SU9516-treated mdx mice produced higher specific force amplitudes (∼26%–29% increase) compared with vehicle-treated counterparts at peak tension (150 Hz) as well as stimulation frequencies within the range of 100–150 Hz (Figure 4D). Diaphragm fatigue was also evaluated, defined as percent decline in amplitude relative to the initial amplitude, after a bout of serial stimulations. No improvements in resistance to fatigue were evident in SU9516-treated mdx diaphragms (Figure 4E); however, after 5 and 10 min of recovery after the fatigue protocol, the SU9516-treated mdx diaphragms recovered to a greater extent (∼8%) compared with the vehicle-treated diaphragms (Figure 4F). Taken together, these results indicate that treatment with the small-molecule compound SU9516 restored mdx body mass and strength toward WT levels.

Studies have shown that the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is structurally and functionally altered in mdx mice.34 To determine whether SU9516 improves NMJ function, we examined muscle force in response to nerve stimulation using a novel optical method. Bright-field videos of phrenic nerve stimulation-induced diaphragm contraction were recorded and post-process analyzed using in-house designed custom software35 (Volumetry G7, G.W.H.). Representative traces of the contractile response, measured as the displacement of an identified region of muscle fiber in response to a train of continuous phrenic nerve stimulations, are depicted in Figure S3A. In response to 10- and 20-Hz nerve stimulation, no differences in peak amplitudes were observed between vehicle and SU9516-treated animals. However, at 40-Hz frequency, the average peak amplitude of displacement attained by the SU9516-treated diaphragms was ∼2.6-fold higher than that of the vehicle group (Figure S3B). Analysis of the integrated area under the curve (AUC) from the contractile responses showed trends toward (not significant) greater cumulative displacement over time in SU9516-treated diaphragms (p = 0.07 for SU9516 versus vehicle at 40 Hz) (Figure S3C). These results suggest that mdx mice exhibit impaired neuromuscular function and that SU516 partially rescues this impairment. To directly test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of sustained phrenic nerve stimulation on acetylcholine (ACh) release by measuring end plate potentials (EPPs) in WT and mdx mice.

The time to 50% EPP amplitude from peak EPP amplitude during 10-Hz stimulation did not vary between WT, vehicle, or SU9516-treated mdx mice and did not reach 50% of peak amplitude within the first 60 s of stimulation (Figure S3D). However, at 20-Hz stimulation frequencies, the vehicle-treated mdx EPP reached half-maximal EPP amplitude significantly faster (Figures S3D and S3E) compared with SU9516-treated mdx mice. Together, these studies show that mdx mice exhibit enhanced synaptic rundown of neurotransmitter release in response to high-frequency nerve stimulation and that treatment with SU9516 partially rescues this deficit.

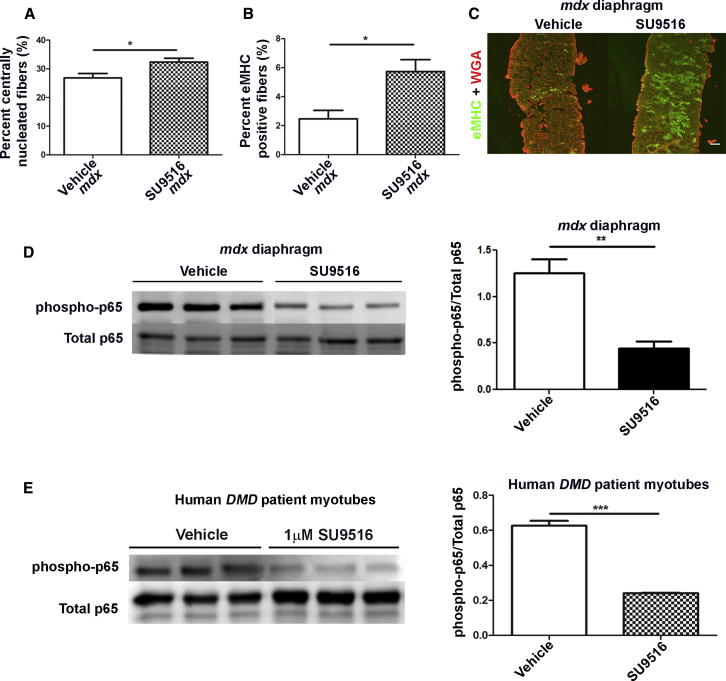

SU9516 Improves Regeneration in the mdx Diaphragm through the Inhibition of the p65-NF-κB Signaling Pathway

To assess the physiologic effects of SU9516 treatment in mdx mice, we performed muscle histological analyses. Histopathological analysis of the diaphragm showed a 5.5% increase in the percentage of centrally nucleated myofibers (a marker of damage and/or regeneration) in SU9516-treated mdx diaphragms relative to vehicle treatment alone (Figure 5A). Furthermore, immunofluorescence for embryonic myosin heavy chain (eMHC)-positive fibers showed an ∼2.5-fold increase in the percentage of eMHC-positive fibers in mdx mouse diaphragms treated with SU9516 relative to vehicle-treated controls (Figures 5B and 5C). It has been shown previously that pharmacological inhibition of the p65-NF-κB pathway in 3-week-old mdx mice increased the number of eMHC fibers by 47%.36 We hypothesized that elevated levels of regeneration seen with SU9516 might be at least partially attributed to the inhibition of the p65-NF-κB pathway. Therefore, lysates from the diaphragms of 10-week-old WT, vehicle, and 5 mg/kg/day SU9516-treated mdx mice were analyzed via western blot for p-p65 NF-κB and normalized to total p65. We found that the SU9516-treated mdx mouse diaphragms had an ∼2.83-fold decrease in the levels of phospho-p65 over total p65 compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 5D). In vitro, treatment of human DMD patient myotubes with 1 μM SU9516 showed a similar 3-fold inhibition of p-p65-NF-κB compared with vehicle-treated myotubes (Figure 5E). These results indicate that SU9516 treatment attenuated the activation of the p65- NF-κB pathway, thereby promoting myofiber regeneration in vivo.

Figure 5.

SU9516 Promotes Myofiber Regeneration through Inhibition of the p65-NF-κB Pathway in mdx Skeletal Muscle

(A) SU9516-treated mdx diaphragms showed a 5.5% increase in the percentage of centrally nucleated fibers over vehicle-treated diaphragms (n = 5/mdx treatment group, Cohen’s d = 1.72). (B) The percentage of eMHC-positive fibers in the diaphragm of SU9516-treated mdx was higher than vehicle-treated mdx by 3.3% (n = 5/mdx treatment group, Cohen’s d = 1.9). (C) eMHC staining in immunofluorescence images of diaphragms from vehicle- and SU9516-treated mdx mice. SU9516-treated diaphragms show an increase in eMHC-positive fibers. (D) SU9516 treatment decreases the level of p-p65-NF-κB by ∼2.83-fold in lysates of mdx diaphragm compared with vehicle-treated controls (n = 3/ mdx treatment group, Cohen’s d = 4.05). (E) Western blot analysis for total phosphorylated p65-NF-κB showed that SU9516 treatment decreases the level of p-p65-NF-κB by >3-fold in human DMD patient myotubes compared with the vehicle-treated counterparts (n = 3 treatments per vehicle or SU9516 group, Cohen’s d = 11.12). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

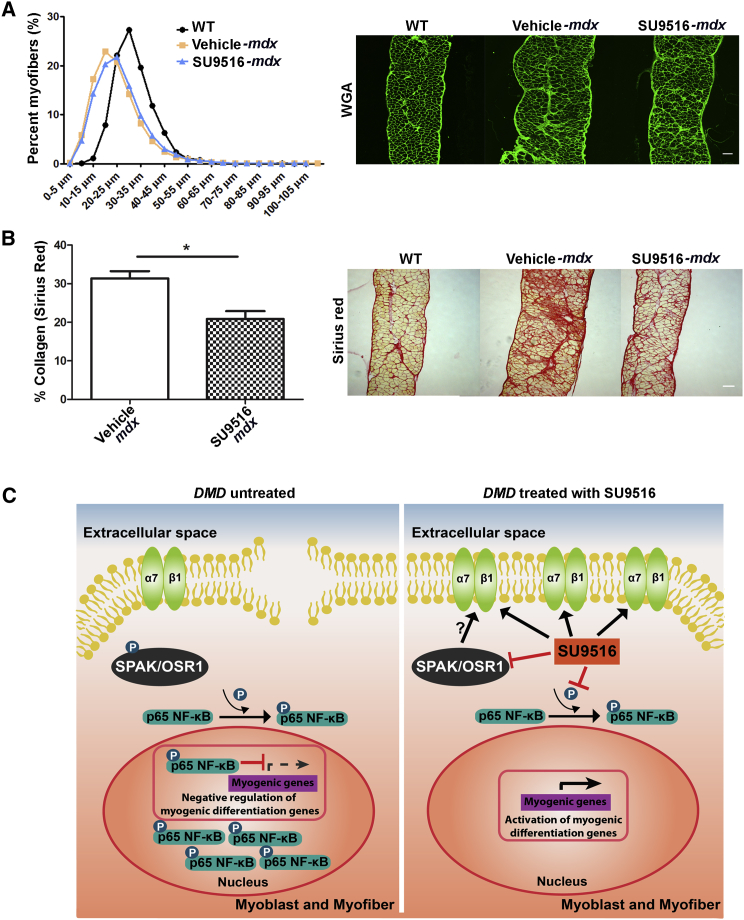

SU9516 Improves Fiber Size and Muscle Regeneration and Reduces Fibrosis in the mdx Diaphragm

Two common histological changes in mdx muscle are changes to fiber diameter and fibrosis. To assess whether SU9516 altered these outcome measures, we performed minimum Feret’s diameter and Sirius Red staining for evaluation of collagen content in the diaphragms of experimental mice. We observed a fiber size shift toward larger fibers in the SU9516-treated mdx muscles relative to the vehicle-treated mdx group (Figure 6A). Sirius red staining showed a decreased area of fibrosis, expressed as a percentage of total area (Figure 6B). Together, these results indicate that SU9516 improved muscle regeneration and reduced pathology in mdx muscle by enhancing sarcolemmal stabilization through elevated α7β1 integrin and also improved regeneration through p65-NF-κB inhibition (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

SU9516 Ameliorates Pathology in mdx Skeletal Muscle

(A) Myofiber size distribution in diaphragms of WT and vehicle- and SU9516-treated mice was assessed utilizing 10-μm cryosections stained with wheat germ agglutinin, followed by minimum Ferret’s diameter measurements. The distribution of fiber size in SU9516-treated diaphragms shifted toward WT fiber size distribution; i.e., larger myofibers. (B) The percent of fibrotic area, as quantified by Sirius Red staining, showed a decrease in collagen-positive areas within the SU9516-treated mdx diaphragm cross-sections compared with vehicle-treated mdx mice (n = 3/mdx treatment group, Cohen’s d = 3.14, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (C) Proposed model for the mechanism of action by which SU9516 ameliorates dystrophic pathology and enhances α7β1 integrin in dystrophic muscle fibers. Values are the mean ± SEM for replicates.

Discussion

This study identifies SU9516 as a novel α7 integrin-enhancing compound in muscle and demonstrates the benefits of using this therapeutic to modify disease progression in the mdx mouse model of DMD. SU9516 is an indolinone compound that has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of CDK2 along with a host of other kinases.37 In vitro experiments in this study showed that SU9516 increased the protein levels of α7B integrin in human DMD patient and C2C12 myogenic cells. Additionally, a 7-week treatment of 5 mg/kg/day SU9516 increased the protein levels of α7B and β1D integrin in the skeletal muscle of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice, thereby demonstrating in vivo on-target activity. In DMD patients, the skeletal muscles progressively weaken, pathology is severe, and patients lose their ability to walk by 13 years of age.38 In mdx mice, however, skeletal muscle pathology is comparatively mild and appears to plateau after 3 months of age. In contrast, the mdx diaphragm is more severely and progressively affected in mdx mice and, thus, more representative of muscle pathology in DMD patients.39 The ex vivo muscle contraction experiments performed in diaphragms of mdx mice showed that SU9516 increased the specific force developed by the mdx diaphragm. Additionally, phrenic nerve stimulation and intracellular recordings of myofibers in the diaphragm showed that SU9516-treated mdx muscles demonstrated higher peak amplitudes of displacement and slowed synaptic fatigue. It is likely that these improvements are partially due to elevated levels of α7β1 integrin in muscle with SU9516 treatment.

Our study also identified SU9516 as an inhibitor of p65-NF-κB signaling activation in skeletal muscle. In mdx mice, increased NF-κB activity exacerbates DMD pathology through increased immune cell activity and the inhibition of myogenic differentiation of muscle precursors.40 Inhibiting NF-κB signaling either genetically or by pharmacological means promoted the formation of new myofibers in response to degeneration.36, 41 Hence, we conclude that the increase in centrally nucleated myofibers and eMHC-positive myofibers seen in the diaphragm of SU9516-treated mdx mice could be attributed to SU9516 inhibition of p65-NF-κB activation. Recently, it was shown that β1 integrin was the sensor of the satellite cell (SC) niche in skeletal muscle and that the activation of β1 integrin signaling in the mdx mouse promoted expansion of the SC population, giving rise to robust myofiber regeneration as well as improved function.42 Hence, it is also possible that SU9516 promotes myofiber regeneration through enhanced expression and activity of β1 integrin.

In addition to blocking CDK2 activity, we determined that, in DMD muscle cells, SU9516 is a potent inhibitor of SPAK/OSR1 kinases (SPAK). Functionally, SPAK kinases are stress sensors that activate the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, having a cell type-dependent and a stimulus-dependent subcellular distribution.43 Importantly, specific stress stimuli, such as hyperosmotic conditions, significantly increased their expression levels and recruitment to membranes of cells.44 Moreover, other authors have shown previously the capacity of p38α to modulate NF-κB transcriptional activation and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) production through phosphorylation of p65-NF-κB, mediated by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1).45 Aligning with these observations, it seems that inhibition of SPAK/OSR1 kinases in DMD muscle cells by SU9516 can downregulate stress-related downstream p65-NF-κB activation. Further pharmacological experiments utilizing STOCK1S-50699, a known inhibitor of SPAK/OSR1, showed that α7 integrin levels increase with suppression of SPAK/OSR1 activity. STOCK1S-50699 is highly hydrophobic, exhibits poor solubility, and cannot be used in animal models, but the data obtained in our experiments provide evidence that development of SPAK/OSR1 inhibitors is feasible for targeting α7 integrin in muscle. Although further experiments are warranted to evaluate the relevance of this pathway in DMD, our results shed light on a novel mechanism of action for the regulation of integrin α7. In our study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that a small-molecule α7β1 integrin-enhancing compound can act to prevent muscle disease progression in the mdx mouse model of DMD. Previous studies have investigated the benefits of utilizing SU9516 as an apoptotic drug for the treatment of leukemia.46 It was observed that, at concentrations of ≥5 μM SU9516, apoptotic pathways were triggered in U937 and other leukemia cell lines. It has been shown that apoptosis is a response to the downregulation of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 with SU9516 treatment.46 This is also the likely explanation for the narrow therapeutic range of SU9516, with toxicity observed at higher doses in the mdx murine model. Hence, derivatives of SU9516 with reduced toxicity are warranted for clinical trials. This study leads the way for further development of small-molecule therapeutics targeting the α7β1 integrin complex in DMD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

To assess the benefits of SU9516 as a therapeutic for DMD, we conducted in vitro experiments to compare α7 integrin levels in murine C2C12 and human DMD myogenic cell lines. These experiments were followed by a preclinical assessment of the drug in mdx mice treated with a dose of 5 mg/kg/day SU9516 for 7 weeks. Assessment of different measurements such as body weight and forelimb grip strength, and ex vivo muscle physiology and quantifications of disease markers such as centrally nucleated fiber counts and Sirius Red and Feret’s diameter of myofibers in diaphragm muscle of mdx mice were performed in a blinded fashion.

Cell Culture

C2C12 myoblasts were originally purchased from the ATCC and grown and maintained in growth medium comprising DMEM (Sigma) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco) + 1% L-Glutamine (Gibco). Myoblasts were maintained below 70% confluence until use in the assay. Myoblasts were differentiated into myotubes in DMEM, 2% horse serum (Atlanta Biologicals), and 1% P/S + L-Glutamine. All cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Assays were performed on myoblasts and myotubes between passages 8 and 14. Human DMD myoblasts were a generous gift from Dr. Kathryn North (The Royal Children’s Hospital) and used under an approved institutional review board (IRB) from the University of Nevada. DMD myogenic cells were cultured as described previously.30 α7+/LacZ myoblasts were originally isolated and maintained as described previously.31 A total of 5,000 α7+/LacZ myoblasts (25,000 for myotube assays) were dispensed in 100 μL growth medium (DMEM without phenol red) using a 12-well multi-pipette (Rainin) onto a Nunc black-sided, tissue culture (TC)-coated, 96-well plate. For myotube formation, differentiation medium was changed daily between 72 and 120 hr. Dose-response curves were generated for SU9516 (Tocris Bioscience) and STOCK1S-50699 (Asinex).

Drug Screen

In collaboration with NCATS Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), the D.J.B. lab identified SU9516 as an enhancer of α7 integrin expression from the LOPAC library. The screen used to identify the compound utilized a myogenic cultured cell line derived from Itga7+/LacZ strain of mice developed in the D.J.B. lab. The cells were derived from heterozygous mice to maintain the α7 integrin protein in these myogenic cells because its loss significantly alters many signaling pathways.31 On the opposing allele, exon 1 of the Itga7 gene was replaced with the LacZ gene. The β-galactosidase expressed from this allele acts as a reporter of Itga7 promoter activity and has been shown previously to mimic normal α7 integrin protein levels during muscle differentiation.31 The enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase levels was then translated into a readable fluorescent signal through the addition and cleavage of fluorescein-di-β-D-galactopyranoside (FDG) to fluorescein.

C2C12 Myotube Analysis

The measurements for myotube width and fusion index were performed according to a protocol modified from Wang et al.47. To analyze myotube diameter, 15 fields were selected randomly, and three myotubes were measured per field. The diameter per myotube was computed as the maximum width taken along the long axis of the myotube. Myotube nuclei were counted in approximately 100 randomly chosen myosin heavy chain (MyHC)-positive myotubes containing two or more nuclei. Myotubes were categorized into five groups (2–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21–25 nuclei per myotube) and were expressed as a percentage of the total myotube number. The fusion index was calculated as the ratio of nuclei in MyHC-positive myotubes to the total number of nuclei in the field for 15 random fields.

KiNativ Assay

A probe-based chemoproteomics (KiNativ) assay was used to identify muscle specific kinase(s) regulated by SU9516.48 DMD myotubes were cultured as described previously30 and treated with 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM SU9516 for 48 hr. Proteins from control and treated DMD myoblasts and myotubes were harvested and incubated with the KiNativ probe (biotinylated acyl phosphates of ATP and ADP) following the manufacturer’s protocol (ActivX Biosciences, Inc., Torrey Pines, CA). Proteins were sent to ActiveX Biosciences and subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to obtain the molecular signature of biotin-labeled proteins in the samples and identify kinases in which activation was inhibited by SU9516.

Immunoblotting

Protein was extracted from cell pellets or tissue powdered in liquid nitrogen. Radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) was used as lysis buffer with a 1:100 dilution of NaF and Na3VO4 and a 1:500 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail. Protein was quantified using a Bradford assay and separated using SDS-PAGE. α7B and β1D integrin were detected as described previously.49 P-p65 and p65-NF-κB antibodies (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology) blotting was followed by rabbit anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology) and WesternSure Premium chemiluminescent substrate (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein loading was normalized to either α-tubulin (1:1,000 mouse-monoclonal, Abcam) or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapDH) (1:1,000, rabbit-monoclonal, Cell Signaling Technology). Quantitation was performed using ImageJ.

Histology and Immunofluorescence

C2C12 cells were grown in chamber slides, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and blocked in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.05% Triton X-100 (American Bioanalytical) for 1 hr at room temperature. The cells were then incubated with the MF20 monoclonal antibody against MHC (1:100, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]) for 2.5 hr and subsequently with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200, Invitrogen) for 1 hr at room temperature. For in vivo immunofluorescence analysis, the hemi-diaphragm was embedded in a mixture of 2:3 (v/v) optimum cutting temperature (OCT) and 30% sucrose. 10-μm sections of diaphragm and gastrocnemius muscles from mice were immunostained using antibodies against α7B integrin and β1D as described previously,25 followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) donkey anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) incubation. Embryonic MHC (mAb 1:50, DSHB) overnight incubation at 4°C was performed on cryosections, followed by 1-hr incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200, Invitrogen). Wheat germ agglutinin (1:1,000) and Sirius Red-stained cryosections were used for minimum Feret’s diameter measurements and percent fibrosis, respectively, using ImageJ. Cell preparations and cryosections were mounted using Vectashield containing DAPI (H-1500, Vector Laboratories). Images were taken using an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 laser confocal microscope.

Animals

It was determined that SU9516 was soluble in 10% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclo-dextrin (HPβCD) and 90% saline (vehicle) and could be delivered by oral gavage. Three-week-old female mdx mice were administered a daily dose of 5 mg/kg SU9516 until 10 weeks of age. Female mdx mice were selected because of availability for the study. All female mdx mice used in the study were homozygous for the DMDmdx allele. All animals were treated according to the rules and regulations specified in the University of Nevada Reno Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). At the end of the study, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia, and the diaphragms were harvested for either contractile measurements33 or phrenic nerve stimulation studies.

Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Studies with SU9516

Initially, it was determined that SU9516 was soluble in 10% HPBCD and 90% saline (vehicle) and could be delivered by oral gavage. For initial PK studies, a single 10 mg/kg SU9516 dose was administered to CD1 mice, after which serum, intestine, and muscle concentrations of SU9516 were determined by mass spectrometry over a 24 hr period.

Forelimb Grip Strength Measurement

Forelimb grip strength was measured with a computerized grip strength meter (Columbus Instruments) according to guidelines published by the Treat-NMD neuromuscular network. The single best recorded value for each mouse is represented in the data analysis.

Intracellular Microelectrode Recording after Phrenic Nerve Stimulation

The diaphragm was dissected and pinned flat in a Sylguard-lined 6-cm Petri dish continuously perfused with a modified Krebs-Ringer solution (NaCl, 121.0 mM; KCl, 5.0 mM; NaHCO3, 24.0 mM; NaH2PO4, 0.4 mM; MgCl2, 0.5 mM; CaCl2, 1.8 mM; glucose, 5.5 mM [continuously gassed with 5% CO2%–95% O2, pH 7.3–7.4]) maintained at 23°C. The phrenic nerve was drawn into a suction electrode and stimulated with suprathreshold square pulses (0.1 ms) using a Grass S48 stimulator coupled to a stimulus isolation unit (Grass, SIU5). EPPs were recorded in the presence of 2.3 μM μ-conotoxin (Peptides International) with borosilicate micro-electrodes (resistance = 30 megohms [MΩ]) filled with 3 M KCl. The endplate region containing neuromuscular junctions was identified by the recording of miniature EPPs with rise-to-peak times of less than 2 ms and was confirmed by post hoc fluorescent α-bungarotoxin labeling. EPPs were only collected from muscle fibers with resting membrane potentials more negative than −65 mV. EPPs were amplified using an Axoclamp 900A amplifier, digitized at 2 KHz using a Digidata 1550, and recorded using Axoscope software before being analyzed with the Clampfit data analysis module within pCLAMP 10 software (Molecular Devices). For synaptic rundown experiments, the phrenic nerve was continuously stimulated for 60 s, and half-maximal EPP amplitudes were measured in relation to the initial EPP. A minimum of three trains of EPPs from each diaphragm was recorded (n = 3). Differences in EPP amplitude as well as time to half-maximal EPP were assessed by unpaired Student’s t tests assuming equal variance.

Functional imaging was performed on a Nikon Eclipse FN1 upright fluorescence microscope using a Nikon Plan Fluor 4×. Image sequences were captured using an Andor Neo (Andor Technology) Scientific Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (sCMOS) camera using Nikon NIS Elements 4.1. Image sequences were recorded at 25 frames/s, processed as 8-bit intensity units, and analyzed using in-house custom-written software (Volumetry G7, G.W.H.).

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software was used to fit dose-response curves using nonlinear regression analysis with log (agonist) versus response with a variable slope. A constraint equal to 1 was placed on the bottom of the curve and either 2 or 2.5 at the top (when needed) to produce appropriate half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values. In all experiments, Student’s t test was used to compare means between two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to compare means of three or more groups, and two-way ANOVA was used in experiments with two independent variables. ANOVA tests were followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Averaged data are reported as the mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cohen’s d effect size was computed and reported to support the Student’s t tests used. We followed Cohen’s range of effect size where small, d = 0.2; medium, d = 0.5; and large, d = 0.8. Additionally, eta-squared η2 was used as a measure of effect size for use in ANOVA, where small η2 = 0.01, medium η2 = 0.06, and large η2 = 0.13.

Author Contributions

A.S., R.D.W., and D.J.B. developed the concept for the study and designed the experiments. L.A.M.G., A.E.D., A.W., X.X., C.Z.C., X.H., W.Z., N.S., M.F., and J.M. performed high-throughput screens. A.S., R.D.W., A.M.N., P.D.B., and T.M.F. performed in vitro cell assays. A.S., A.R.T., T.M.F., D.J.H., S.D., and T.W.G. performed functional assays. A.S., R.D.W., and D.J.B. wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The University of Nevada, Reno has a patent pending for the therapeutic use of SU9516 and derivatives for muscular dystrophy that has been licensed to StrykaGen Corp. The patent inventors are D.J.B. and R.D.W. D.J.B. and R.D.W. are the founder and co-founder, respectively, of StrykaGen Corp., and the University of Nevada, Reno has a small equity share in this company.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NIAMS R01AR053697 and R01AR064338, CureCMD, Struggle against Muscular Dystrophy, and R41AR067014 (to D.J.B.). A.S. and T.M.F. are supported by Mick Hitchcock scholarships. NCATS was funded by the NIH Intramural Research Program. A.N. is supported by a fellowship SFRH/BD/86985/2012 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. The materials described in this manuscript are available through a mutually agreed MTA.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes three figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.022.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Mendell J.R., Shilling C., Leslie N.D., Flanigan K.M., al-Dahhak R., Gastier-Foster J., Kneile K., Dunn D.M., Duval B., Aoyagi A. Evidence-based path to newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2012;71:304–313. doi: 10.1002/ana.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunckley M.G., Manoharan M., Villiet P., Eperon I.C., Dickson G. Modification of splicing in the dystrophin gene in cultured Mdx muscle cells by antisense oligoribonucleotides. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1083–1090. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilton S.D., Honeyman K., Fletcher S., Laing N.G. Snapback SSCP analysis: engineered conformation changes for the rapid typing of known mutations. Hum. Mutat. 1998;11:252–258. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:3<252::AID-HUMU11>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson G., Azad A., Morris G.E., Simon H., Noursadeghi M., Walsh F.S. Co-localization and molecular association of dystrophin with laminin at the surface of mouse and human myotubes. J. Cell Sci. 1992;103:1223–1233. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ervasti J.M., Campbell K.P. A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:809–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klietsch R., Ervasti J.M., Arnold W., Campbell K.P., Jorgensen A.O. Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex and laminin colocalize to the sarcolemma and transverse tubules of cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 1993;72:349–360. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrof B.J., Shrager J.B., Stedman H.H., Kelly A.M., Sweeney H.L. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:3710–3714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald C.M., Henricson E.K., Abresch R.T., Han J.J., Escolar D.M., Florence J.M., Duong T., Arrieta A., Clemens P.R., Hoffman E.P., Cnaan A., Cinrg Investigators The cooperative international neuromuscular research group Duchenne natural history study--a longitudinal investigation in the era of glucocorticoid therapy: design of protocol and the methods used. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48:32–54. doi: 10.1002/mus.23807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houde S., Filiatrault M., Fournier A., Dubé J., D’Arcy S., Bérubé D., Brousseau Y., Lapierre G., Vanasse M. Deflazacort use in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an 8-year follow-up. Pediatr. Neurol. 2008;38:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beenakker E.A., Fock J.M., Van Tol M.J., Maurits N.M., Koopman H.M., Brouwer O.F., Van der Hoeven J.H. Intermittent prednisone therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:128–132. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushby K., Finkel R., Birnkrant D.J., Case L.E., Clemens P.R., Cripe L., Kaul A., Kinnett K., McDonald C., Pandya S., DMD Care Considerations Working Group Diagnosis and management of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, part 1: diagnosis, and pharmacological and psychosocial management. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:77–93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gloss D., Moxley R.T., 3rd, Ashwal S., Oskoui M. Practice guideline update summary: Corticosteroid treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2016;86:465–472. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schara U., Mortier, Mortier W. Long-Term Steroid Therapy in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy-Positive Results versus Side Effects. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2001;2:179–183. doi: 10.1097/00131402-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAdam L.C., Mayo A.L., Alman B.A., Biggar W.D. The Canadian experience with long-term deflazacort treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol. 2012;31:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young C.S., Pyle A.D. Exon Skipping Therapy. Cell. 2016;167:1144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lostal W., Kodippili K., Yue Y., Duan D. Full-length dystrophin reconstitution with adeno-associated viral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2014;25:552–562. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odom G.L., Gregorevic P., Allen J.M., Chamberlain J.S. Gene therapy of mdx mice with large truncated dystrophins generated by recombination using rAAV6. Mol. Ther. 2011;19:36–45. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng J., Counsell J.R., Reza M., Laval S.H., Danos O., Thrasher A., Lochmüller H., Muntoni F., Morgan J.E. Autologous skeletal muscle derived cells expressing a novel functional dystrophin provide a potential therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19750. doi: 10.1038/srep19750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerletti M., Negri T., Cozzi F., Colpo R., Andreetta F., Croci D., Davies K.E., Cornelio F., Pozza O., Karpati G. Dystrophic phenotype of canine X-linked muscular dystrophy is mitigated by adenovirus-mediated utrophin gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2003;10:750–757. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burkin D.J., Wallace G.Q., Nicol K.J., Kaufman D.J., Kaufman S.J. Enhanced expression of the alpha 7 beta 1 integrin reduces muscular dystrophy and restores viability in dystrophic mice. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:1207–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burkin D.J., Wallace G.Q., Milner D.J., Chaney E.J., Mulligan J.A., Kaufman S.J. Transgenic expression of alpha7beta1 integrin maintains muscle integrity, increases regenerative capacity, promotes hypertrophy, and reduces cardiomyopathy in dystrophic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62249-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. The alpha7beta1 integrin in muscle development and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s004410051279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao Z.Z., Lakonishok M., Kaufman S., Horwitz A.F. Alpha 7 beta 1 integrin is a component of the myotendinous junction on skeletal muscle. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:579–589. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.2.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin P.T., Kaufman S.J., Kramer R.H., Sanes J.R. Synaptic integrins in developing, adult, and mutant muscle: selective association of alpha1, alpha7A, and alpha7B integrins with the neuromuscular junction. Dev. Biol. 1996;174:125–139. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song W.K., Wang W., Sato H., Bielser D.A., Kaufman S.J. Expression of alpha 7 integrin cytoplasmic domains during skeletal muscle development: alternate forms, conformational change, and homologies with serine/threonine kinases and tyrosine phosphatases. J. Cell Sci. 1993;106:1139–1152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.4.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rooney J.E., Welser J.V., Dechert M.A., Flintoff-Dye N.L., Kaufman S.J., Burkin D.J. Severe muscular dystrophy in mice that lack dystrophin and alpha7 integrin. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2185–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Increasing alpha 7 beta 1-integrin promotes muscle cell proliferation, adhesion, and resistance to apoptosis without changing gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C627–C640. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welser J.V., Rooney J.E., Cohen N.C., Gurpur P.B., Singer C.A., Evans R.A., Haines B.A., Burkin D.J. Myotendinous junction defects and reduced force transmission in mice that lack alpha7 integrin and utrophin. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:1545–1554. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boppart M.D., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Activation of AKT signaling promotes cell growth and survival in α7β1 integrin-mediated alleviation of muscular dystrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wuebbles R.D., Sarathy A., Kornegay J.N., Burkin D.J. Levels of α7 integrin and laminin-α2 are increased following prednisone treatment in the mdx mouse and GRMD dog models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013;6:1175–1184. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rooney J.E., Gurpur P.B., Burkin D.J. Laminin-111 protein therapy prevents muscle disease in the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7991–7996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lane M.E., Yu B., Rice A., Lipson K.E., Liang C., Sun L., Tang C., McMahon G., Pestell R.G., Wadler S. A novel cdk2-selective inhibitor, SU9516, induces apoptosis in colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6170–6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moorwood C., Liu M., Tian Z., Barton E.R. Isometric and eccentric force generation assessment of skeletal muscles isolated from murine models of muscular dystrophies. J. Vis. Exp. 2013;71:e50036. doi: 10.3791/50036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons P.R., Slater C.R. Structure and function of the neuromuscular junction in young adult mdx mice. J. Neurocytol. 1991;20:969–981. doi: 10.1007/BF01187915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hennig G.W., Spencer N.J., Jokela-Willis S., Bayguinov P.O., Lee H.T., Ritchie L.A., Ward S.M., Smith T.K., Sanders K.M. ICC-MY coordinate smooth muscle electrical and mechanical activity in the murine small intestine. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010;22:e138–e151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acharyya S., Villalta S.A., Bakkar N., Bupha-Intr T., Janssen P.M., Carathers M., Li Z.W., Beg A.A., Ghosh S., Sahenk Z. Interplay of IKK/NF-kappaB signaling in macrophages and myofibers promotes muscle degeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:889–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI30556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moshinsky D.J., Bellamacina C.R., Boisvert D.C., Huang P., Hui T., Jancarik J., Kim S.H., Rice A.G. SU9516: biochemical analysis of cdk inhibition and crystal structure in complex with cdk2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;310:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman E.P., Brown R.H., Jr., Kunkel L.M. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stedman H.H., Sweeney H.L., Shrager J.B., Maguire H.C., Panettieri R.A., Petrof B., Narusawa M., Leferovich J.M., Sladky J.T., Kelly A.M. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991;352:536–539. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hindi S.M., Sato S., Choi Y., Kumar A. Distinct roles of TRAF6 at early and late stages of muscle pathology in the mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:1492–1505. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson J.M., Kline W., Canan B.D., Ricca D.J., Kaspar B., Delfín D.A., DiRienzo K., Clemens P.R., Robbins P.D., Baldwin A.S. Peptide-based inhibition of NF-κB rescues diaphragm muscle contractile dysfunction in a murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Med. 2011;17:508–515. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozo M., Li L., Fan C.M. Targeting β1-integrin signaling enhances regeneration in aged and dystrophic muscle in mice. Nat. Med. 2016;22:889–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston A.M., Naselli G., Gonez L.J., Martin R.M., Harrison L.C., DeAizpurua H.J. SPAK, a STE20/SPS1-related kinase that activates the p38 pathway. Oncogene. 2000;19:4290–4297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zagórska A., Pozo-Guisado E., Boudeau J., Vitari A.C., Rafiqi F.H., Thastrup J., Deak M., Campbell D.G., Morrice N.A., Prescott A.R., Alessi D.R. Regulation of activity and localization of the WNK1 protein kinase by hyperosmotic stress. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:89–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson C.M., Hedrick M.N., Izadi H., Bates T.C., Olivera E.R., Anguita J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase controls NF-kappaB transcriptional activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha production through RelA phosphorylation mediated by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 in response to Borrelia burgdorferi antigens. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:270–277. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01412-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao N., Kramer L., Rahmani M., Dent P., Grant S. The three-substituted indolinone cyclin-dependent kinase 2 inhibitor 3-[1-(3H-imidazol-4-yl)-meth-(Z)-ylidene]-5-methoxy-1,3-dihydro-indol-2-one (SU9516) kills human leukemia cells via down-regulation of Mcl-1 through a transcriptional mechanism. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:645–655. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M., Amano S.U., Flach R.J., Chawla A., Aouadi M., Czech M.P. Identification of Map4k4 as a novel suppressor of skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;33:678–687. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00618-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patricelli M.P., Szardenings A.K., Liyanage M., Nomanbhoy T.K., Wu M., Weissig H., Aban A., Chun D., Tanner S., Kozarich J.W. Functional interrogation of the kinome using nucleotide acyl phosphates. Biochemistry. 2007;46:350–358. doi: 10.1021/bi062142x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boppart M.D., Burkin D.J., Kaufman S.J. Alpha7beta1-integrin regulates mechanotransduction and prevents skeletal muscle injury. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1660–C1665. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00317.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.