Abstract

Objective

To examine potential neural substrates that underlie the interplay between religiosity/spirituality and risk-for-depression. A new wave of data from a longitudinal, three generation study of individuals at high risk for depression is presented. In addition to providing new longitudinal data, we extend previous findings by employing additional (surface-based) methods for examining cortical volume.

Measures, Participants, and Methods

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were collected on 106 second and third generation family members at high or low risk for major depression defined by the presence or absence of depression in the first generation. Religiosity/spirituality measures were collected at the same time as the MRI scans and comprised self-report ratings of personal religious/spiritual (R/S) importance and frequency of religious attendance. Analyses were carried out with Freesurfer. Interactive effects of religiosity/spirituality and risk-for-depression were examined on measures of cortical thickness and cortical surface area.

Results

A high degree of belief in the importance of religion/spirituality was associated with both a thicker cortex and a larger pial surface area in persons at high risk for familial depression. No significant association was found between cortical regions and religious attendance in either risk group.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results support previous findings of an association between R/S importance and cortical thickness in individuals at high risk for depression, and extend the findings to include an association between R/S importance and greater pial surface area. Moreover, the findings suggest these cortical changes may confer protective benefits to religious/spiritual individuals at high risk for depression.

Keywords: depression, religion/spirituality, functional magnetic imaging (MRI), cortical thickness, pial surface

Religiosity and spirituality play a central role in the lives of many people. Despite several empirical studies on this topic, our understanding of the neural substrates of religiosity and spirituality remain little understood. The available evidence from the recent past seems to converge on the involvement of nearly every brain lobe in religious/spiritual experiences (Beauregard, Courtemanche, & Paquette, 2009; Borg, Andree, Soderstrom, & Farde, 2003; Devinsky & Lai, 2008; Goodman, 2002; Krause, Emmons, & Ironson, 2015; Newberg, 2014; Pelletier-Baldelli et al., 2014). Moreover, studies tend to be based on either healthy populations or clinical samples of ill people receiving treatment (Kapogiannis et al., 2009; Urgesi, Aglioti, Skrap, & Fabbro, 2010), but few have been conducted on populations at risk for developing an illness.

Research from our group has examined the neural underpinnings of religiosity/spirituality in families at risk for familial depression. These studies derive from 6 waves of data sampled over a 30-year span from three generations of families at risk for major depressive disorder (Weissman et al., 2016). In brief, we have found belief in the high importance of religion/spirituality (R/S) to be associated with biological markers of resilience in at-risk individuals, including thicker cortices (Miller et al., 2014), greater EEG alpha (Tenke et al., 2013), and decreased default mode network connectivity (Svob et al., 2016). In the present study, we follow up on Miller et al.’s (2014) findings of an association between R/S importance and cortical thickness in high-risk individuals in a new wave of data (collected 8 years later) from the same longitudinal sample. In addition to cortical thickness, we also examine the association between R/S importance and pial surface area.

Pial surface area offers a complementary measure of cortical morphology that focuses on cortical surface area, rather than cortical thickness. With advances in magnetic resonance image (MRI) data processing, it is possible to separate cortical area and cortical thickness. By examining pial surface area, we will be able to provide a more complete picture of cortical morphometric differences in high- and low-risk individuals for depression and examine these associations in relation to R/S importance.

In previous studies, we found widespread reductions in cortical thickness in high-risk individuals (Peterson, et al., 2009). Miller et al. (2014) reported greater cortical thickness in the same brain regions that showed cortical thinning in high-risk individuals that reported high R/S importance, suggesting that among those at clinical risk, the presence of R/S importance may serve as a resilience factor that helps to buffer the biological risks leading to clinical symptoms. In the present study, we expect to replicate Miller et al.’s findings of cortical thickness and extend them to include greater cortical surface areas in religious/spiritual at-risk individuals. We hypothesize that religiosity/spirituality will have an impact on the association between risk status and both measures of cortical volume: cortical thickness and cortical area. If these results hold up, they will support previous findings on cortical thickness and extend this work to include measures of cortical surface area, thus creating a more holistic picture of the brain morphology implicated in the potentially protective aspects of R/S importance in people at-risk for depression.

Method

Participants

The sample included second- and third-generation offspring from an ongoing longitudinal study on people at high risk for depression. The design of the multiwave 3-generation study is described in detail in our earlier publications (Weissman, Leckman, Merikangas, Gammon, & Prusoff, 1984; Weissman, Warner, Wickramaratne, Moreau, & Olfson, 1997; Weissman et al., 2006; Weissman, Berry, Warner, Gameroff, Skipper, Talati, et al., 2016a; Weissman, Wickramaratne, Gameroff, Warner, Pilowsky, Kohad, et al., 2016b). The original proband group (generation 1, G1) consisted of adult Caucasians receiving psychopharmacologic treatment for depression (high-risk) and a demographically matched non-depressed comparison group from the same community (low-risk). Subjects were eligible for the current study if they completed clinical assessments, religious question items, and MRI scanning at the 30-year follow-up (Wave 6). The final study cohort in this report constitutes 47 offspring (generation 2, G2) and 59 grandchildren (generation 3, G3) of the G1 probands. High- and low-risk status for depression in G2 and G3 family members was determined by depression diagnoses in G1s (Table 1). Of the 106 eligible participants, 57 were G2 or G3 members of affected G1 probands, comprising the high-risk offspring group. The remaining 49 participants constituted the low-risk offspring group. At the 30-year follow-up, all offspring underwent clinical assessments using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia—Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (Mannuzza, Fyer, Klein, & Endicott, 1986), or the Kiddie-SADS (epidemiological version K-SADS-E) for those under the age of 17 years (Orvaschel, Puig-Antich, Chambers, Tabrizi, & Johnson, 1982). Assessments were administered by experienced clinicians blind to familial status and subject’s clinical status. The study was approved by The New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University Institutional Review Board. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 106 participants at the 30-year follow-up

| Mean | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.5 | 13.6 |

| N | % | |

| Female | 55 | 52% |

| Religiosity | ||

| Personal importance of religion/spirituality | ||

| High | 21 | 20% |

| Moderate | 40 | 37% |

| Slight | 25 | 24% |

| None | 20 | 19% |

| Frequent attendance at religious/spiritual services | ||

| Once a week or more | 14 | 13% |

| About once a month | 19 | 18% |

| Once or twice a year | 27 | 25% |

| Less than once a year | 11 | 10% |

| Never | 35 | 33% |

| Religious denomination | ||

| Protestant | 12 | 11% |

| Catholic | 57 | 54% |

| Jewish | 3 | 3% |

| Personal religious | 15 | 14% |

| Agnostic/Atheist | 11 | 10% |

| Other | 5 | 5% |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| High risk | 57 | 54% |

| Low risk | 49 | 46% |

Religion and Spirituality Measures

R/S importance was assessed with a single self-report item: How important to you is religion or spirituality? (1 = not important at all, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = highly important). This single-item measure has been shown to be highly reliable when compared to the widely used Fetzer Institute Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness (Desrosiers & Miller, 2007; Idler et al., 2003). In the present cohort, 21 participants rated R/S as highly important, 40 as moderately important, 25 as slightly important, and 20 as not important at all. Based on our previous findings, out of three basic R/S measures, the degree of importance was most strongly associated with preventive effects against depression (Miller et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2012). To be consistent with this literature for comparative purposes, the measure of R/S importance was treated as a binary variable and was dichotomized into high importance (ratings = 4) and low importance (ratings < 4).

We also collected self-report ratings on the frequency of attending religious services: How often, if at all, do you attend church, synagogue, or other religious or spiritual services? (1 = once a week or more, 2 = about once a month, 3 = about once or twice a year, 4 = less than once a year, 5 = never). The results of religious attendance were not statistically significant and are not reported.

The self-report ratings were obtained at the same time as the MRI data.

MRI Acquisition

Anatomical scans were collected on a 3-Tesla GE Signa EXCITE scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, USA) at the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University. High-resolution T1-weighted MRI images were acquired axially using a three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient-echo (3D-FSPGR) sequence with the following scanning parameters: TR = 6.02ms, TI = 500ms, TE = 2.38ms, flip angle = 11°, matrix = 256×256, slice thickness = 1mm, and number of slices = 162 per volume.

Image Processing

Cortical surface reconstruction was performed using Freesurfer Software Suite (version 5.3, http://freesurfer.net/). A detailed description of the technical characteristic of Freesurfer is documented elsewhere (Fischl et al., 2004). In brief, Freesurfer’s automated processing stream included the removal of non-brain tissue, intensity normalization, Talairach registration, segmentation of white matter, gray/white matter boundary tessellation, and deformation of gray/white surface outward to locate gray/cerebrospinal fluid borders (pial surface). Output of cortical reconstruction for each participant was visually inspected for quality assurance. Inaccuracies were manually corrected when necessary. Each surface comprised approximately 160,000 vertices arranged in a mesh of triangles. Cortical thickness at each vertex was measured as the shortest distance between the pial surface and white matter surface, whereas the pial surface area was quantified as the aggregate area from each triangle. Next, reconstructed surfaces of each participant were aligned to the common reference brain. Surfaces were further smoothed by a Gaussian kernel with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 10 mm to increase the signal-to-noise ratio.

Statistical Analyses

Whole-brain vertex-wise analyses were carried out in the Query Design Estimate Contrast (QDEC) toolkit from Freesurfer (Hagler, Saygin, & Serano, 2006). Interactive effects of R/S importance and risk-for-depression on brain morphological measures (cortical thickness and pial surface area) were examined vertex by vertex using a linear least-squares regression model with age as a nuisance variable. Analyses were performed in each hemisphere separately. To control for multiple comparisons at vertex-wise threshold of 0.05, a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations was implemented in determining a cluster-size threshold p < 0.05. Because of our prime interest in the R/S importance x risk interaction, surface-based morphological measures were extracted from clusters surviving clusterwise correction for subsequent simple effect analysis. If R/S importance × risk interaction effects were significant, simple effects were further examined in Stata (Version 14, StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

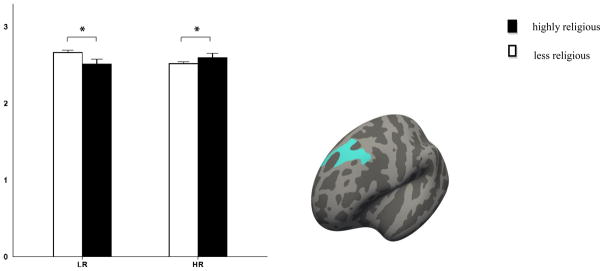

As hypothesized, greater cortical thickness was observed in people at high-risk for depression who also reported R/S to be of high importance. Cortical thickness was observed in the left superior frontal gyrus. Follow-up simple effect analyses within each risk group revealed a contrasting effect of R/S importance on familial risk (see Table 2 and Figure 1). That is, subjects in the low-risk group who reported high R/S importance had a thinner superior frontal cortex (F(1,101) = 5.85, p = 0.0174), whereas high ratings of R/S importance in the high-risk group were associated with a thicker cortex in the same region (F(1,101) = 4.24, p = 0.0421).

Table 2.

Religiosity × risk for depression interaction effects on brain morphological measures

| Region | Hemisphere | Size (mm2) | X | Y | Z | Clusterwise p value | Num. of vertices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical thickness | |||||||

| Superior frontal | L | 1128.98 | −14.5 | 42.1 | 42.3 | 0.0244 | 1987 |

| Pial surface area | |||||||

| Isthmus cingulate | L | 2217.99 | −7.2 | −37.8 | 32.9 | 0.0002 | 5241 |

| Middle temporal | L | 3278.85 | −64.4 | −27.8 | −14.8 | 0.0001 | 5385 |

| Precentral | L | 2615.14 | −45.8 | −8.9 | 26.7 | 0.0001 | 6249 |

| Lateral occipital | L | 5392.88 | −22.5 | −93.5 | 14.6 | 0.0001 | 7798 |

| Rostral middle frontal | L | 2355.63 | −36.7 | 44.6 | 14.3 | 0.0001 | 3278 |

| Superior frontal | L | 1284.24 | −6.7 | 22.8 | 57.2 | 0.0211 | 2202 |

| Inferior parietal | R | 3187.51 | 46.7 | −74.2 | 10.9 | 0.0001 | 4535 |

| Inferior temporal | R | 1701.71 | 57.3 | −27.7 | −28.4 | 0.0034 | 2825 |

| Superior frontal | R | 1766.94 | 8.7 | 60.1 | 21.8 | 0.0025 | 2513 |

| Superior temporal | R | 1248.72 | 53.8 | 6.1 | −11.7 | 0.0278 | 2008 |

Figure 1.

Regions where interaction effects were significant between religiosity and risk for depression on cortical thickness (mm). Error bar represents standard errors. * Indicates p < 0.05. LR: low-risk; HR: high-risk.

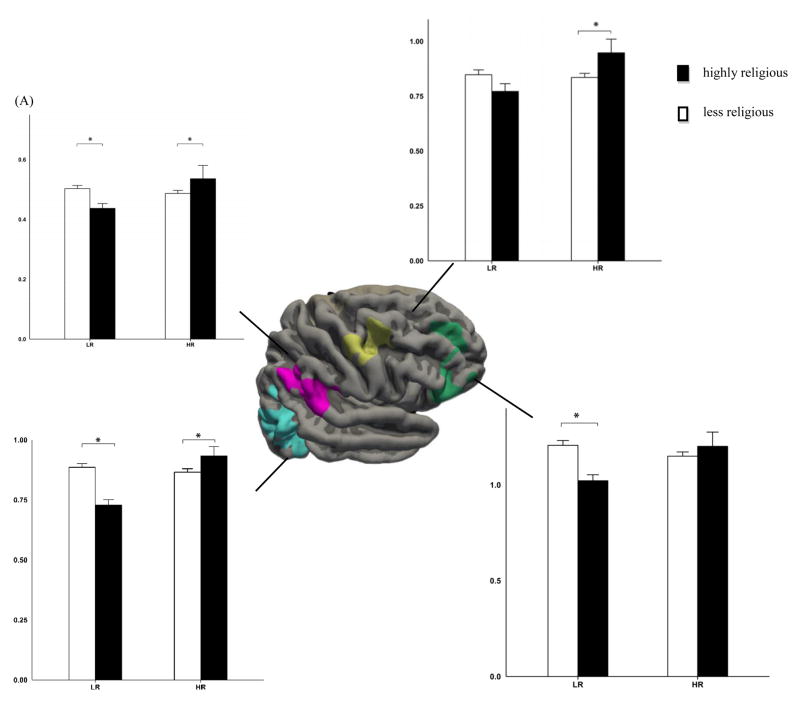

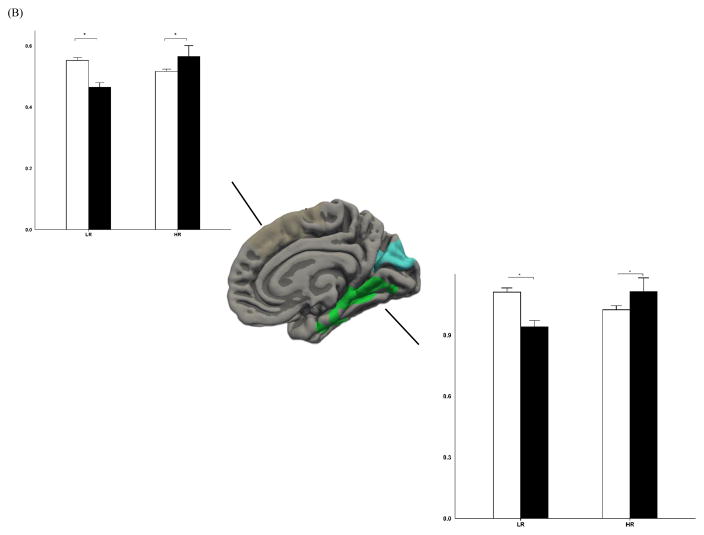

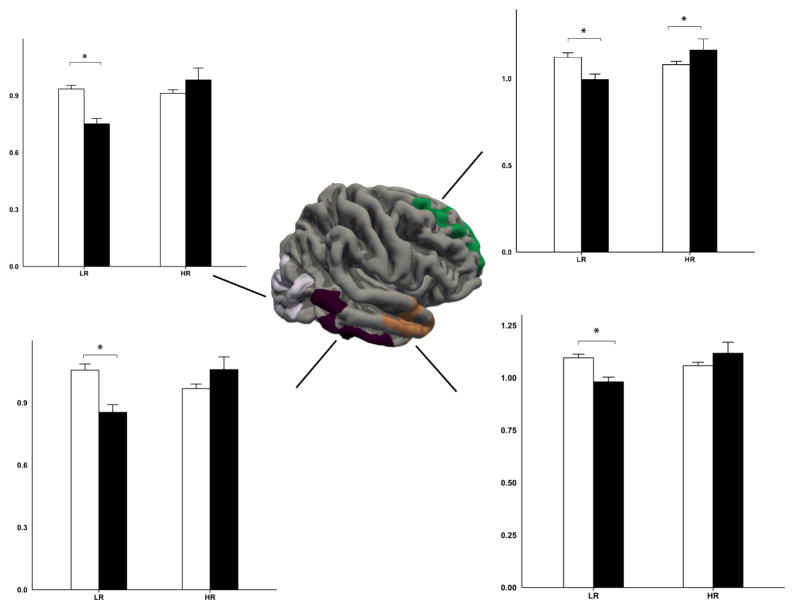

We also found a significant interaction between R/S importance and risk for cortical surface areas in multiple regions (see Table 2 and Figure 2–3). Further stratified analyses on the significant clusters demonstrated a consistent pattern of varying effects of R/S importance on pial surface area depending on familial risk status. High R/S importance was related to a smaller pial surface area in the low-risk group across the identified brain regions; this pattern was reversed in the high-risk group where larger pial surface areas were observed for individuals who reported high R/S importance (specifically, in the left isthmus cingulate, F(1,101) = 5.75, p = 0.0183 and F(1,101) = 5.67, p = 0.0191 for the low-risk and high-risk group respectively; F(1,101) = 12.54, p = 0.0006 / F(1,101) = 6.52, p = 0.0121 in the middle temporal gyrus; F(1,101) = 16.46, p = 0.0001 / F(1,101) = 6.03, p = 0.0158 in the precentral gyrus; F(1,101) = 21.23, p < 0.0001 / F(1,101) = 4.74, p = 0.0319 in the lateral occipital complex; F(1,101) = 11.44, p < 0.001 / F(1,101) = 3.01, p = 0.0858 in the rostral middle frontal gyrus; F(1,101) = 2.1, p < 0.1502 / F(1,101) = 6.67, p = 0.0112 in the superior frontal cortex; F(1,101) = 15.97, p < 0.0001 / F(1,101) = 2.82, p = 0.0962 in the right inferior parietal lobule; F(1,101) = 11.90, p < 0.0008 / F(1,101) = 3.86, p = 0.0522 in the inferior temporal cortex; F(1,101) = 5.63, p < 0.0195 / F(1,101) = 5.51, p = 0.0208 in the superior frontal gyrus; F(1,101) = 7.87, p < 0.006 / F(1,101) = 3.38, p = 0.069 in the superior temporal cortex).

Figure 2.

Lateral (A) and medial (B) view of regions where interaction effects were significant between religiosity and risk for depression on scaled surface area in the left hemisphere. Error bar represents standard errors. * Indicates p < 0.05. LR: low-risk; HR: high-risk.

Figure 3.

Lateral view of regions where interaction effects were significant between religiosity and risk for depression on scaled surface area in the right hemisphere. Error bar represents standard errors. * Indicates p < 0.05. LR: low-risk; HR: high-risk.

There were also statistically significant effects observed for risk-for-depression on cortical thickness (p < 0.05, corrected): the high-risk group had a thinner cortex in the right superior frontal gyrus as compared to the low-risk group. Further, main effects of risk status were observed in pial surface areas (p < 0.05, corrected), with the high-risk group revealing larger surface areas in the left isthmus cingulate, right posterior cingulate cortex, and bilateral lateral occipital complex and superior frontal gyrus. Significant main effects of R/S importance were observed in the region of the left cuneus, rostral middle frontal gyrus, right entorhinal cortex, lateral orbito frontal cortex, and bilateral lateral occipital complex (see Table 1S).

To test the potentially confounding effect of depression, we repeated the analyses with sex and lifetime depression as covariates in the model. This did not change the pattern of results in a meaningful way, suggesting that the neuropathology of depression is unlikely a confounding variable in our findings.

Discussion

Cortical thickness and surface area were measured in 106 subjects in which 57 subjects had a family history of depression. R/S importance, but not religious attendance, was associated with greater cortical volume, including cortical thickness and cortical surface area, respectively, in offspring at high familial risk. R/S importance × risk effects were present in regions spanning multiple lobes, as evidenced by an increase of cortical thickness and surface area uniquely in high-risk subjects who reported a high degree of R/S importance. These region-specific effects remained stable even after controlling for past and present symptoms of depression. Hence, our study supports previous findings of cortical thickness (Miller et al., 2014) and extends them to include the additional dimension of cortical surface area.

Despite the similarities between the present study and Miller et al.’s (2014), there were also notable differences. As already mentioned, both studies found that R/S importance was associated with cortical thickness and that this association varied significantly by familial risk status, with the association being stronger in the high-risk group as compared with the low-risk group. The specific areas of the brain that differed in cortical thickness, however, did not always coincide. That is, Miller et al. found cortical thickness particularly along the mesial wall of the left hemisphere. We also found these effects in the left hemisphere, but in the superior frontal gyrus. The discrepancy could be due to methodological differences between the two studies, including (a) non-overlapping samples (Wave 5 versus Wave 6), (b) different assessment waves (Miller et al. used R/S measures cumulated over multiple waves as opposed to a single R/S measure concurrent in time with the measures of cortical thickness that were used in the present study), (c) different MRI machines (1.5 versus 3 Tesla), and (d) different analytical software. Although the specific regions with cortical thickness did not overlap between the two studies, the overall effect remained – R/S importance was associated with greater cortical thickness in people at high risk for depression.

It should also be emphasized that our study focused less on the sole effect of R/S importance and more on it interacting with familial predispositions for major depressive disorder. The current findings lend support to the hypothesized role of R/S importance interacting with risk at a neurological level. That is, the magnitude of associations between R/S importance and neuroanatomical features (cortical thickness, surface area) varied substantially with risk status for depression. Remarkably, all of the significant brain clusters exhibited the same pattern of interaction: R/S importance was characteristically associated with cortical thickening and enlargement in solely the high-risk group.

We chose to examine two quantitative neuroanatomical traits (i.e., cortical thickness and surface area) in our search for the neural correlates of R/S importance and risk. Our results were particularly pronounced with regard to surface area, relative to cortical thickness. This observation was unexpected. As previously mentioned, brain volume is a composite measure that depends on both thickness and surface area. We “decomposed” the cortical volume into two dimensions to thoroughly capture potential R/S importance and risk effects (cortical thickness along the vertical dimension and surface area along the horizontal dimension). Specifically, our vertex-wise analyses criss-crossed the entire cortical architecture three-dimensionally, examining cortical laminar and columnar organization in the form of thickness and area. It is important to note that a body of work has demonstrated that cortical thickness and area are two closely related, but distinct, properties of cortical organization (Bois et al., 2015; Chenn & Walsh, 2003; Ohta et al., 2016; Panizzon et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2015). These two topographical properties have been shown to be regulated by largely non-overlapping ontogenetic and genetic determinants. That is, thickness formation is largely a consequence of the migration of precursor cells, whereas the expansion of cortical surface areas results from the proliferation of precursor cells once they reach their final destination (Chenn & Walsh, 2003). Human twin studies have shown that thickness and surface area are both highly heritable, but the genetic correlation between them is markedly low, suggesting a differential genetic influence over them (Panizzon et al., 2009). Moreover, studies involving children with autism spectrum disorder have revealed abnormalities in surface area, but precluded noticeable differences in cortical thickness (Ohta et al., 2016). It has been recommended that cortical thickness and surface area, given their independent utility and complementary advantages, are equally crucial for identifying neuroanatomical phenotypes (Winkler et al., 2010). Admittedly, the exact mechanisms by which R/S importance and risk interact with surface area more than cortical thickness remain obscure. The patterns herein, however, hint that associations between R/S importance, risk, and cortical structures may vary differentially with respect to the anatomical features under examination.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution in light of a number of limitations. First, our sample size was relatively small. Second, the impact of the R/S importance × risk interaction, as we have observed, manifests in macrostructural brain alterations. A question remains as to how R/S importance and risk interact at the molecular level that eventually cascades into changes in cortical thickness and surface area. This is beyond the scope of the current study. Third, we cannot rule out the possibility that other unidentified factors may directly or indirectly contribute to our observed R/S importance and risk effects. For example, R/S importance may act as a surrogate for multiple environmental forces, such as parenting, family orientation, and peer support (Duriez, Soenens, Neyrinck, & Vansteenkiste, 2009; Sabatier, Mayer, Friedlmeier, Lubiewska, & Trommsdorff, 2011). It is not yet clear whether a moderating influence can be attributed to R/S importance alone or whether a combination of other factors is implicated in the personal endorsement of R/S importance. Finally, given the fact that both of our main measures (MRI and self-report ratings of R/S importance) were obtained at the same time point (Wave 6), we are unable to make any causal claims regarding the association between R/S importance and cortical volume and are limited to reporting correlational findings.

To conclude, this study provides an account of the neural correlates of R/S importance and familial risk for depression. Cortical thickness and enlarged cortical surface areas were observed for subjects who reported high R/S importance in the high-risk group as opposed to the low-risk group. The significant interactions we observed between R/S importance and risk status constituted a replication of previous findings on cortical thickness (Miller et al., 2014) and extended them through the inclusion of pial surface areas. This data on cortical surface area provides a new potential biomarker of R/S importance and familial risk for depression. Moreover, religious attendance was not associated with any statistically significant effects (similar to Miller et al., 2014), suggesting that R/S importance, and not religious attendance, may be implicated in protection against risk for depression at the neurological level. Our findings suggest the need to take R/S importance into account in future studies of imaging endophenotypes for depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the John Templeton Foundation (54679; M. Weissman, P.I.), NIMH (R01 MH-036197; M. Weissman, P.I.), the Sackler Institute for Developmental Biology (J. Gingrich, P.I.), and the Silvio O. Conte Center (IP50MH090966; J. Gingrich, P.I.).

References

- Baker SC, Frith CD, Dolan RJ. The interaction between mood and cognitive function studied with PET. Psychol Med. 1997;27(3):565–578. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton YA, Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Weissman MM. Religious attendance and social adjustment as protective against depression: A 10-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;146(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.037. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard M, Courtemanche J, Paquette V. Brain activity in near-death experiencers during a meditative state. Resuscitation. 2009;80(9):1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois C, Ronan L, Levita L, Whalley HC, Giles S, McIntosh AM, … Lawrie SM. Cortical surface area differentiates familial high risk individuals who go on to develop schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(6):413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J, Andree B, Soderstrom H, Farde L. The serotonin system and spiritual experiences. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):1965–1969. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito NH, Noble KG. Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:276. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenn A, Walsh CA. Increased neuronal production, enlarged forebrains and cytoarchitectural distortions in beta-catenin overexpressing transgenic mice. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(6):599–606. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers A, Miller L. Relational spirituality and depression in adolescent girls. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(10):1021–1037. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky O, Lai G. Spirituality and religion in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(4):636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duriez B, Soenens B, Neyrinck B, Vansteenkiste M. Is religiosity related to better parenting? Disentangling religiosity from religious cognitive style. Journal of Family Issues. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0192513x09334168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Segonne F, Salat DH, … Dale AM. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(1):11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman N. The serotonergic system and mysticism: could LSD and the nondrug-induced mystical experience share common neural mechanisms? J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(3):263–272. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler DJ, Saygin AP, Sereno MI. Smoothing and cluster thresholding for cortical surface-based group analysis of fMRI data. Neuroimage. 2006;33:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenkamp W, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Duncan E, Barsalou LW. Mind wandering and attention during focused meditation: a fine-grained temporal analysis of fluctuating cognitive states. Neuroimage. 2012;59(1):750–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Verosky SC, Germine LT, Knight RT, D’Esposito M. Neural activity during social signal perception correlates with self-reported empathy. Brain Res. 2010;1308:100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, … Williams DR. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging. 2003;25(4):327–365. doi: 10.1177/0164027503025004001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M, Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff M, Weissman MM. Family religion and psychopathology in children of depressed mothers: ten-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapogiannis D, Barbey AK, Su M, Zamboni G, Krueger F, Grafman J. Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(12):4876–4881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasen S, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Weissman MM. Religiosity and resilience in persons at high risk for major depression. Psychol Med. 2012;42(3):509–519. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Emmons RA, Ironson G. Benevolent images of God, gratitude, and physical health status. J Relig Health. 2015;54(4):1503–1519. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Champagne FA. Early-life experience, epigenetics, and the developing brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):141–153. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ, Klein DF, Endicott J. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia--Lifetime Version modified for the study of anxiety disorders (SADS-LA): rationale and conceptual development. J Psychiatr Res. 1986;20(4):317–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(86)90034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Bansal R, Wickramaratne P, Hao X, Tenke CE, Weissman MM, Peterson BS. Neuroanatomical correlates of religiosity and spirituality: a study in adults at high and low familial risk for depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):128–135. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Sage M, Tenke CE, Weissman MM. Religiosity and major depression in adults at high risk: a ten-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):89–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberg AB. The neuroscientific study of spiritual practices. Front Psychol. 2014;5:215. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Beer JS, Robertson ER, Cooper JC, Gabrieli JD, Kihsltrom JF, D’Esposito M. The neural correlates of direct and reflected self-knowledge. Neuroimage. 2005;28(4):797–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Nordahl CW, Iosif AM, Lee A, Rogers S, Amaral DG. Increased Surface Area, but not Cortical Thickness, in a Subset of Young Boys With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2016;9(2):232–248. doi: 10.1002/aur.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers W, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-e. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1982;21(4):392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Eyler LT, Jernigan TL, Prom-Wormley E, Neale M, … Kremen WS. Distinct genetic influences on cortical surface area and cortical thickness. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(11):2728–2735. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier-Baldelli A, Dean DJ, Lunsford-Avery JR, Smith Watts AK, Orr JM, Gupta T, … Mittal VA. Orbitofrontal cortex volume and intrinsic religiosity in non-clinical psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;222(3):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Warner V, Bansal R, Zhu H, Hao X, Liu J, Durkin K, Adams PB, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM. Cortical thinning in persons at increased familial risk for major depression. Proceeding from the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:6273–6278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805311106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier C, Mayer B, Friedlmeier M, Lubiewska K, Trommsdorff G. Religiosity, family orientation, and life satisfaction of adolescents in four countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0022022111412343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svob C, Wang Z, Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Posner J. Religious and spiritual importance moderate relation between default mode network connectivity and familial risk for depression. Neuroscience Letters. 2016;634:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley D, Stowe CJ, Huettel SA. Altruism is associated with an increased neural response to agency. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(2):150–151. doi: 10.1038/nn1833. doi: http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v10/n2/suppinfo/nn1833_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(10):1114–1133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenke CE, Kayser J, Miller L, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM, Bruder GE. Neuronal generators of posterior EEG alpha reflect individual differences in prioritizing personal spirituality. Biological Psychology. 2013;94:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urgesi C, Aglioti SM, Skrap M, Fabbro F. The spiritual brain: selective cortical lesions modulate human self-transcendence. Neuron. 2010;65(3):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace GL, Eisenberg IW, Robustelli B, Dankner N, Kenworthy L, Giedd JN, Martin A. Longitudinal cortical development during adolescence and young adulthood in autism spectrum disorder: increased cortical thinning but comparable surface area changes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(6):464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leckman JF, Merikangas KR, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA. Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children. Results from the Yale family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(9):845–852. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790200027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Moreau D, Olfson M. Offspring of depressed parents. 10 Years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(10):932–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220054009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Berry OO, Warner V, Gameroff MJ, Skipper J, Talati A, Pilowsky D, Wickramaratne P. A 30-year study of 3 generations at high risk and low risk risk for depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016a;73:970–977. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff M, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Kohad RG, Verdeli H, Skipper J, Talati A. Offspring of depressed parents: 30 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016b doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15101327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Kochunov P, Blangero J, Almasy L, Zilles K, Fox PT, … Glahn DC. Cortical thickness or grey matter volume? The importance of selecting the phenotype for imaging genetics studies. Neuroimage. 2010;53(3):1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.