Abstract

Objective To characterize rates and trends over time of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death within 30 days of discharge from observation stays.

Design Retrospective cohort study.

Setting 4750 hospitals in the USA.

Participants Nationally representative sample of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries aged 65 or over discharged after 363 037 index observation stays, 2 540 000 index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and 2 667 525 index inpatient stays from 2006-11.

Main outcome measures Rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death within 30 days of discharge from index observation stays. Rates were compared with corresponding outcomes within 30 days of discharge from both index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays and index inpatient stays.

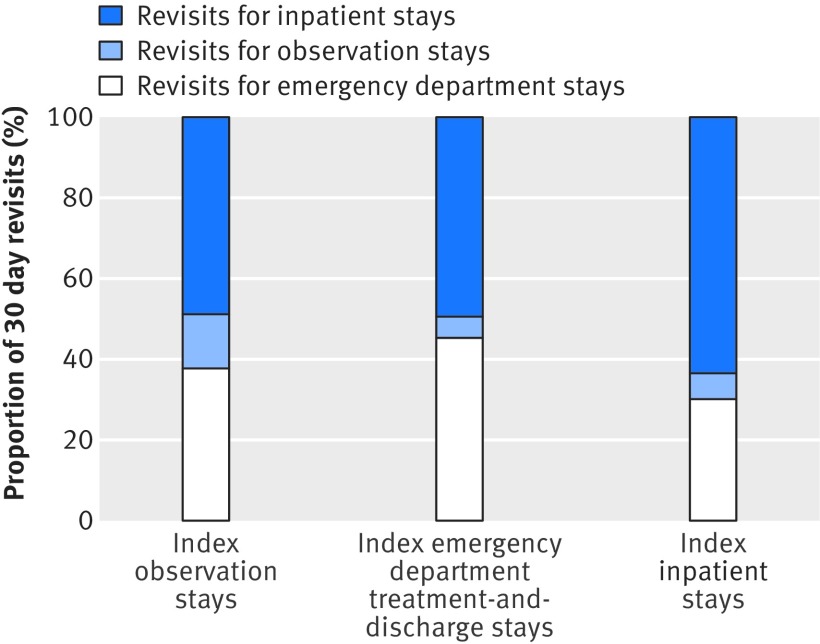

Results Among 363 037 index observation stays resulting in discharge from 2006-11, 30 day rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays were 8.4%, repeat observation stays were 2.9%, inpatient stays were 11.2%, any hospital revisit was 20.1%, and death was 1.8%. Of all revisits, 49.7% were for inpatient stays. Revisit rates for emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, and any hospital revisit increased from 2006-11 (P<0.001 for trend), while 30 day rates of inpatient stays (P=0.054 for trend) and 30 day mortality (P=0.091 for trend) were both unchanged. Averaged over the study period, 30 day rates of any hospital revisit were similar after discharge from index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays (19.9%) and index observation stays (20.1%), as was 30 day mortality (1.8% for both). Rates of any hospital revisit (21.8%) and death (5.2%) were highest after discharge from index inpatient stays.

Conclusions Hospital revisits are common after discharge from observation stays, frequently result in inpatient hospitalizations, and have increased over time among Medicare beneficiaries. As revisit rates are similar after emergency department and observation stays, strategies shown to enhance emergency department transitional care may be reasonable starting points to improve post-observation outcomes.

Introduction

Observation stays are being increasingly used as an alternative to short stay hospitalizations for adults aged 65 or more in the USA. Observation stays typically follow emergency department care and are meant to provide short term treatment and frequent reassessment for inpatient hospitalization.1 2 Although technically considered an outpatient service, observation stays can physically occur in the emergency department, in a dedicated hospital observation unit, or in the inpatient hospital setting. Patients receiving observation services may share a room with other patients receiving emergency department care or inpatient care. Observation stays are generally reimbursed less generously than inpatient stays. Payers (including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) have encouraged the use of observation stays rather than inpatient hospitalizations by implementing several policies such as payment denials, rate modifications, and additional regulatory levers.3 4 5 In this setting, the annual prevalence of observation stays among Medicare beneficiaries increased dramatically to over one million visits a year by 2009.6 7 By 2013, approximately 1.5 million Medicare beneficiaries received observation services on a yearly basis.2 See box 1 for greater detail on the Medicare program and its policies regarding observation stays. A patient may receive care during an observation stay in the USA for the purposes of clinical observation or if higher payment for inpatient care is not anticipated. As a result, observation stays do not always reflect the clinical need for inpatient hospital care as they might in other countries but are rather an unanticipated result of financial incentives.

Box 1: Descriptions of Medicare and observation stays

Medicare

Medicare is the USA federal health insurance program for people aged 65 and over, those with certain disabilities, or those with end stage renal disease requiring dialysis or renal transplant. Medicare is administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which is a division of the US Department of Health & Human Services

Medicare is an entitlement program, and most Americans have the right to enroll in Medicare by working and paying taxes for a minimum required period. Medicare provides health insurance for approximately 50 million Americans and pays for approximately one half of US hospital inpatient costs. Approximately 70% of older Americans have traditional Medicare health insurance, or Medicare fee for service, while 30% have Medicare Advantage, a form of managed medical care in which health benefits are administered and managed by a private health insurance company

Beneficiaries with traditional Medicare health insurance generally have greater choice of providers at the expense of additional health costs from deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurance8 9

Observation stays

Observation stays are defined by CMS as a “well-defined set of specific, clinically appropriate services, which include ongoing short term treatment, assessment, and reassessment before a decision can be made regarding whether patients will require further treatment as hospital inpatients or if they are able to be discharged from the hospital.”

Observation stays are most commonly used for patients who are initially treated in an emergency department, though can be used in other circumstances, such as after selected outpatient procedures.

Observation stays can occur in multiple settings, including in a dedicated observation unit, in an emergency department, or on a hospital inpatient floor. Diagnostic tests, procedures, and other treatments are generally considered appropriate for observation stays when the treating provider expects the patient to remain in the hospital for less than 24 hours, or less than 48 hours under exceptional circumstances. In contrast, diagnostic tests, procedures, and other treatments are generally considered appropriate for inpatient hospital stays when the treating provider expects the patient to require a longer hospital stay

CMS pays hospital facilities for observation stays on an hourly basis under Medicare Part B, which covers outpatient services and supplies. In contrast, CMS pays for inpatient hospital stays under Medicare Part A using predetermined payments that are partly based on the medical condition responsible for the hospital stay

Observation stays are generally reimbursed less generously than inpatient stays. As a result, payers, including CMS, have progressively implemented several policies such as payment denials, rate modifications, and additional regulatory levers to encourage use of observation stays rather than inpatient hospital stays. As a result of these incentives, many short stays in hospital that were historically treated as inpatient hospital stays under Medicare Part A are now treated as outpatient observation stays under Medicare Part B.1 10 11

Patients receiving observation services may end up with higher medical bills, as Medicare does not cover the cost of routine maintenance drugs the hospital provides for the treatment of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, nor does it cover the costs for follow-up care in a nursing home12

While observation stays have grown in importance for the care of people aged 65 years or over, our understanding of outcomes after discharge from observation services remains limited. Previous studies of post-hospital outcomes have examined a small number of conditions treated during observation stays, such as chest pain13 14 15 16 and heart failure,17 or were based on estimates from a small number of hospitals that may not be broadly generalizable.13 18 19 In contrast, studies utilizing large nationally representative databases that describe the range of conditions treated using observation services have not included information on outcomes after discharge.6 20 21 This gap in knowledge about observation stays contrasts with the extensive literature describing outcomes after discharge from emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays and inpatient stays.22 23 24 25 As a result, outstanding questions remain about rates of occurrence of hospital revisits, including emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, inpatient stays, and any hospital revisit after discharge from index observation stays; rates of occurrence of death after discharge from index observation stays; potential differences in revisit and mortality outcomes after discharge from index observation stays compared with outcomes after discharge from index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays and index inpatient stays; and changes in outcomes over time. These estimates are critical to understanding the vulnerabilities experienced by patients after discharge form observation services and can guide the design of hospital and health system transitional care interventions to mitigate these risks. These data can also help benchmark quality improvement efforts and contribute to the development of quality metrics that measure and report outcomes after discharge from observation stays in parallel with metrics for patients discharged from emergency departments26 27 and inpatient care.28

To estimate revisit and mortality outcomes after discharge from index observation stays in the USA, we examined a nationally representative sample of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries aged 65 years and over receiving observation services from 2006-11. Medicare is the largest payer of healthcare for older adults in the USA,29 has actively stimulated greater use of observation services,3 4 5 and increased focus on post-hospital stay outcomes.30 31 Among Medicare beneficiaries, we characterized rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death within 30 days of discharge from index observation stays. To contextualize these outcomes, we compared them with rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death within 30 days of discharge from both index emergency department stays and index inpatient stays. We hypothesized that revisit rates and mortality after discharge from index observation stays would be intermediate between corresponding outcomes after discharge from index emergency department and inpatient stays.

Methods

Datasets

We used Standard Analytic Files for Medicare fee for service beneficiaries aged 65 years and over from 2006-11 to examine index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, inpatient stays, and associated outcomes within 30 days of discharge. These datasets are produced on a yearly basis by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and contain complete inpatient and outpatient administrative data for a representative 5% of Medicare fee for service beneficiaries.32 We identified enrollment status in Medicare fee for service using Medicare denominator files; observation stays and emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays in Medicare hospital outpatient files; and inpatient stays in Medicare hospital inpatient files.

Study cohorts

For our primary study population, we identified unscheduled observation stays using revenue center code 0762 or revenue center code 0760 in combination with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code G0378. We included index observation stays of patients aged 65 years and over on the date of admission to observation services with at least 30 days of pre-observation enrollment in Medicare fee for service and 30 days of post-discharge enrollment in Medicare fee for service in the absence of death. We excluded index observation stays resulting in death in hospital, observation stays resulting in transfer to another acute care facility, and observation stays resulting in discharge against medical advice. Index observation stays resulting in inpatient admission were also excluded as these patients are largely considered to have first required inpatient hospital stays, and our aim was to examine post-hospital outcomes of people discharged after receipt of observation services.

For our comparator populations, we identified index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays using revenue center codes 0450 to 0459 and 0981, as has been done previously.33 Inpatient stays were pre-identified in inpatient Standard Analytic Files. We included care episodes of patients aged 65 years and over on the date of admission with at least 30 days of pre-admission enrollment in Medicare fee for service and 30 days of post-discharge enrollment in Medicare fee for service in the absence of death. We excluded index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays and inpatient stays resulting in death in hospital, transfer to another acute care facility, or discharge against medical advice.

In parallel with the disease specific readmission measures used by CMS to evaluate hospital readmission performance, we did not include 30 day revisits for the same type of event as the index event within study cohorts. For example, we did not include 30 day revisits for observation stays after an index observation stay in the observation stay cohort. We did, however, include 30 day revisits for different categories of events compared with the index event in their respective cohorts. For example, we included 30 day revisits for observation stays and inpatient stays after an emergency department treatment-and-discharge stay in our index cohorts of observation stays and inpatient stays, respectively. We chose this approach since outcomes associated with revisits differ from outcomes associated with index stays.34 Exclusion of all revisits from index cohorts would therefore result in non-representative patient samples.

We restricted our analyses to Medicare fee for service beneficiaries aged 65 years and over because younger fee for service beneficiaries are a distinct population who qualify for early receipt of Medicare health insurance due to disabilities. This population is more likely to be from racial and ethnic minority groups, be in fair or poor health, have low income and education levels, and live without a partner.35 This group is also more likely to report problems with access to care and more likely to experience both emergency department stays and inpatient stays.35

Sample classification

We classified all index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays by their principal discharge diagnoses. To do so, we utilized Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality that clusters more than 14 000 ICD-9-CM (international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification) diagnosis codes into 285 clinically meaningful, single level CCS categories.36 CCS grouping has been used previously with observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays.20 21 37 38 39

Outcomes

Our main outcomes measures were rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death within 30 days of discharge from index observation stays. Rates were compared with corresponding outcomes within 30 days of discharge from both index emergency department stays and index inpatient stays.

To avoid double counting hospital revisits, we considered index emergency department stays that subsequently resulted in observation stays or inpatient stays to be index observation stays and inpatient stays, respectively. Similarly, we considered index observation stays that subsequently resulted in inpatient stays to be inpatient stays.

In addition, because emergency department administrative claims are often present concurrently with claims for observation stays, we conservatively did not consider overlapping emergency department claims present during an index observation stay or the day after an index observation stay to represent a separate emergency department stay.

Statistical analysis

For each study year, we calculated descriptive statistics for age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidities among index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays. We tested for trend across study years using linear regression for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables.

For both the entire study period and each study year, we calculated rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, inpatient stays, any hospital revisit, and death in the 30 days after discharge from index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays. We calculated confidence intervals for these estimates using the exact binomial confidence interval.40 For all observation stays we assumed an admission time of 12 pm. We determined the day of discharge by counting the total hours for which observation services were provided as reported in the service units field of the administrative data, as has been done previously.6 Using χ2 tests we compared revisit rates and mortality after index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays.

All significance levels were two sided, with P<0.05 considered to be significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Patient involvement

Patients, service users, carers, or lay people were not directly involved in the design of this study. As this study concerned examination of existing administrative claims data of more than two million unique patients, no participants were specifically recruited for this analysis. The study’s focus on hospital revisit and mortality outcomes after index observation stays is consistent with the increasing focus on end results of healthcare rather than process measures or intermediate outcomes that do not directly result in benefits to patients.

Results

We included 363 037 index observation stays from 278 530 unique patients, 2 540 000 index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays from 1 093 786 unique patients, and 2 667 525 index inpatient stays from 1 156 675 unique patients from 2006-11. Flow diagrams describing reasons for exclusion from each cohort are shown in supplementary figures 1A-C in the web appendix. Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients treated during index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays. The average age, proportion female, and proportion white were similar among all three cohorts. Between 2006 and 2011, the number of index observation stays increased (P=0.01 for trend), the number of index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays remained the same (P=0.26 for trend), and the number of index inpatient stays decreased (P=0.01 for trend) (table 1). In addition, between 2006 and 2011, increases were seen in the frequency of many chronic conditions in all three cohorts, including Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and diabetes (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of index observation stays, index emergency department stays, and index inpatient stays by year from 2006 to 2011. Values are percentages (numbers) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Year | Slope (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||

| Index observation stays | |||||||

| Total | 51 938 | 54 378 | 57 239 | 62 865 | 66 725 | 69 892 | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 77.7 (7.8) | 77.9 (7.8) | 78.0 (8.0) | 78.2 (8.1) | 78.3 (8.1) | 78.3 (8.2) | 0.12 (0.10 to 0.13) |

| Male | 34.5 (17 912) | 34.8 (18 913) | 34.4 (19 704) | 34.8 (21 899) | 34.8 (23 219) | 34.6 (24 193) | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.01) |

| Ethnicity: | −0.05 (−0.05 to −0.04) | ||||||

| White | 89.1 (46 272) | 88.3 (48 023) | 88.4 (50 606) | 87.8 (55 225) | 87.1 (58 130) | 86.5 (60 435) | |

| Black | 7.7 (4018) | 7.9 (4308) | 7.8 (4439) | 8.3 (5206) | 8.6 (5736) | 9.1 (6387) | |

| Other | 3.2 (1648) | 3.8 (2047) | 3.8 (2194) | 3.9 (2434) | 4.3 (2859) | 4.4 (3070) | |

| Medicaid | 17.4 (9056) | 17.6 (9579) | 17.9 (10 224) | 18.0 (11 316) | 18.7 (12 487) | 19.1 (13 345) | 0.02 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| Comorbidities: | |||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders | 20.7 (10 754) | 21.7 (11 818) | 22.7 (12 975) | 23.8 (14 983) | 24.6 (16 398) | 25.2 (17 606) | 0.05 (0.05 to 0.06) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.6 (1337) | 2.6 (1426) | 2.8 (1615) | 2.5 (1593) | 2.8 (1859) | 2.7 (1887) | 0.01 (−0.00 to 0.02) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 17.7 (9208) | 18.0 (9807) | 18.3 (10 496) | 18.7 (11 738) | 19.1 (12 721) | 19.8 (13 825) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| Cataract | 26.2 (13 624) | 25.1 (13 651) | 24.1 (13 776) | 23.3 (14 664) | 22.4 (14 915) | 21.5 (15 021) | −0.05 (−0.06 to −0.05) |

| Heart failure | 37.6 (19 544) | 37.8 (20 531) | 37.2 (21 299) | 37.3 (23 461) | 37.2 (24 792) | 37.2 (25 991) | −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.00) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 21.6 (11 235) | 24.2 (13 152) | 25.9 (14 847) | 28.2 (17 743) | 30.5 (20 362) | 32.0 (22 397) | 0.11 (0.10 to 0.11) |

| Female breast cancer | 3.2 (1646) | 3.1 (1694) | 3.2 (1826) | 3.1 (1977) | 3.0 (2001) | 5.6 (3895) | 0.11 (0.10 to 0.12) |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.7 (891) | 1.7 (903) | 1.6 (907) | 1.6 (1026) | 1.5 (969) | 2.9 (2021) | 0.09 (0.08 to 0.11) |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.3 (132) | 0.2 (117) | 0.2 (143) | 0.3 (164) | 0.3 (172) | 0.6 (445) | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.24) |

| Lung cancer | 2.1 (1073) | 2.0 (1101) | 2.1 (1188) | 2.0 (1227) | 1.9 (1301) | 2.4 (1692) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) |

| Prostate cancer | 3.7 (1928) | 3.9 (2127) | 3.7 (2123) | 3.7 (2334) | 3.6 (2376) | 4.8 (3349) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 23.0 (11 956) | 23.4 (12 748) | 23.3 (13 351) | 23.5 (14 742) | 23.9 (15 962) | 26.4 (18 447) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Depression | 21.1 (10 961) | 22.0 (11 982) | 23.7 (13 583) | 24.8 (15 619) | 26.1 (17 411) | 28.8 (20 118) | 0.08 (0.08 to 0.09) |

| Diabetes | 33.5 (17 409) | 35.0 (19 059) | 35.6 (20 377) | 36.2 (22 757) | 37.3 (24 889) | 38.0 (26 585) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Glaucoma | 11.4 (5902) | 11.6 (6294) | 11.5 (6589) | 11.7 (7330) | 11.7 (7800) | 11.7 (8157) | 0.01 (−0.00 to 0.01) |

| Hip or pelvic fracture | 1.7 (907) | 1.7 (931) | 1.8 (1035) | 1.9 (1173) | 2.0 (1305) | 2.2 (1541) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.06) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 60.6 (31 472) | 61.0 (33 145) | 61.2 (35 022) | 61.2 (38 495) | 61.3 (40 931) | 60.7 (42 451) | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.01) |

| Osteoporosis | 19.3 (10 047) | 19.7 (10 699) | 20.6 (11 805) | 20.9 (13 123) | 20.8 (13 849) | 14.6 (10 229) | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.04) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 31.8 (16 529) | 32.6 (17 714) | 33.6 (19 249) | 34.9 (21 925) | 35.4 (23 615) | 49.7 (34 734) | 0.13 (0.13 to 0.13) |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 11.8 (6114) | 12.4 (6767) | 12.8 (7303) | 12.8 (8035) | 12.9 (8600) | 12.9 (9044) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.02) |

| Index emergency department stays | |||||||

| Total | 424 228 | 416 820 | 415 328 | 417 357 | 428 756 | 437 511 | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 77.9 (8.0) | 78.0 (8.1) | 78.0 (8.1) | 78.1 (8.2) | 78.1 (8.3) | 78.1 (8.4) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05) |

| Male | 33.1 (140 355) | 33.5 (139 789) | 33.5 (139 292) | 33.9 (141 479) | 34.0 (145 850) | 34.4 (150 612) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.01) |

| Ethnicity: | −0.02 (−0.02 to −0.02) | ||||||

| White | 85.3 (361 990) | 85.4 (355 801) | 85.3 (354 136) | 84.9 (354 340) | 84.6 (362 649) | 84.4 (369 232) | |

| Black | 10.3 (43 702) | 10.2 (42 604) | 10.2 (42 233) | 10.4 (43 389) | 10.6 (45 498) | 10.7 (46 710) | |

| Other | 4.4 (18 536) | 4.4 (18 415) | 4.6 (18 959) | 4.7 (19 628) | 4.8 (20 609) | 4.9 (21 569) | |

| Medicaid | 20.8 (88 308) | 20.7 (86 294) | 21.0 (87 345) | 21.0 (87 515) | 21.4 (91 624) | 21.4 (93 754) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.01) |

| Comorbidities: | |||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders | 23.1 (98 182) | 23.8 (99 338) | 24.5 (101 798) | 25.2 (105 066) | 25.5 (109 541) | 25.2 (110 287) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.2 (9274) | 2.1 (8958) | 2.3 (9512) | 2.2 (9083) | 2.3 (9729) | 2.2 (9431) | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.01) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 15.3 (64 884) | 15.6 (64 951) | 15.5 (64 467) | 16.1 (67 244) | 16.5 (70 830) | 16.8 (73 566) | 0.02 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| Cataract | 24.8 (105 141) | 24.3 (101 395) | 23.1 (96 003) | 22.8 (95 346) | 21.8 (93 317) | 21.1 (92 131) | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.04) |

| Heart failure | 34.3 (145 564) | 33.9 (141 215) | 33.5 (139 268) | 33.5 (139 612) | 33.0 (141 686) | 32.4 (141 943) | −0.02 (−0.02 to −0.01) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 19.3 (81 969) | 21.7 (90 428) | 23.1 (96 148) | 25.2 (105 376) | 27.2 (116 732) | 28.4 (124 366) | 0.10 (0.10 to 0.10) |

| Female breast cancer | 2.3 (9808) | 2.4 (9936) | 2.5 (10 211) | 2.4 (10 202) | 2.5 (10 591) | 4.7 (20 468) | 0.13 (0.13 to 0.13) |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.4 (5866) | 1.4 (5714) | 1.4 (5663) | 1.3 (5611) | 1.3 (5674) | 2.4 (10 691) | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.11) |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.2 (909) | 0.2 (852) | 0.2 (894) | 0.2 (900) | 0.2 (960) | 0.5 (2267) | 0.18 (0.16 to 0.19) |

| Lung cancer | 1.7 (7048) | 1.7 (7140) | 1.8 (7379) | 1.8 (7339) | 1.8 (7649) | 2.1 (9065) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Prostate cancer | 3.4 (14 282) | 3.4 (14 269) | 3.4 (13 979) | 3.4 (14 023) | 3.3 (13 974) | 4.2 (18 544) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20.9 (88 491) | 21.0 (87 639) | 21.3 (88 304) | 21.3 (89 067) | 21.7 (92 997) | 23.5 (102 912) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| Depression | 20.0 (84 933) | 20.7 (86 307) | 22.3 (92 434) | 23.2 (96 700) | 24.1 (103 537) | 26.0 (113 939) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.07) |

| Diabetes | 33.2 (140 717) | 34.1 (142 212) | 34.9 (144 806) | 35.6 (148 403) | 36.1 (154 747) | 36.7 (160 719) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.03) |

| Glaucoma | 11.5 (48 681) | 11.4 (47 671) | 11.6 (48 146) | 11.7 (48 657) | 11.6 (49 661) | 11.8 (51 481) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) |

| Hip or pelvic fracture | 2.1 (9098) | 2.2 (8999) | 2.1 (8717) | 2.1 (8968) | 2.1 (9094) | 2.3 (10 059) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.02) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 51.0 (216 290) | 51.1 (213 189) | 51.1 (212 225) | 51.4 (214 321) | 51.1 (219 289) | 50.6 (221 280) | -0.00 (-0.00 to -0.00) |

| Osteoporosis | 18.6 (78 842) | 18.8 (78 487) | 19.5 (80 887) | 19.7 (82 159) | 19.5 (83 596) | 13.1 (57 309) | −0.05 (−0.05 to −0.05) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 30.8 (130 711) | 31.2 (129 994) | 32.0 (132 789) | 32.9 (137 518) | 33.5 (143 478) | 46.3 (202 638) | 0.11 (0.11 to 0.11) |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 10.3 (43 856) | 10.3 (43 054) | 10.1 (42 138) | 10.1 (42 132) | 10.1 (43 163) | 9.8 (42 907) | −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.01) |

| Index inpatient stays | |||||||

| Total | 480 572 | 464 172 | 455 082 | 426 878 | 424 641 | 416 180 | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 78.6 (8.0) | 78.7 (8.0) | 78.7 (8.1) | 78.7 (8.2) | 78.7 (8.3) | 78.8 (8.4) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) |

| Male | 36.8 (176 733) | 37.0 (171 618) | 37.2 (169 207) | 37.4 (159 690) | 37.9 (160 795) | 38.3 (159 246) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.01) |

| Ethnicity: | −0.02 (−0.02 to −0.01) | ||||||

| White | 86.7 (416 757) | 86.8 (403 053) | 86.6 (394 317) | 86.4 (368 755) | 86.1 (365 774) | 86.0 (357 810) | |

| Black | 9.2 (44 295) | 9.0 (41 582) | 9.0 (40 936) | 9.2 (39 345) | 9.3 (39 694) | 9.4 (39 145) | |

| Other | 4.1 (19 520) | 4.2 (19 537) | 4.4 (19 829) | 4.4 (18 778) | 4.5 (19 173) | 4.6 (19 225) | |

| Medicaid | 18.5 (88 955) | 18.4 (85 226) | 18.6 (84 501) | 18.7 (79 844) | 19.1 (81 103) | 19.2 (79 734) | 0.01 (0.01 to 0.01) |

| Comorbidities: | |||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders | 26.8 (128 607) | 27.4 (127 031) | 28.0 (127 615) | 28.8 (122 852) | 29.2 (123 826) | 29.9 (124 524) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.03) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5.6 (26 733) | 5.6 (26 096) | 5.8 (26 379) | 5.6 (23 966) | 5.8 (24 419) | 5.7 (23 793) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23.8 (114 311) | 23.8 (110 348) | 23.0 (104 446) | 24.1 (102 715) | 24.5 (104 181) | 25.0 (104 143) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.02) |

| Cataract | 22.1 (106 310) | 21.3 (98 957) | 20.2 (91 972) | 20.3 (86 501) | 19.2 (81 590) | 18.4 (76 525) | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.04) |

| Heart failure | 49.7 (238 757) | 48.7 (226 271) | 48.2 (219 342) | 48.3 (206 345) | 48.0 (203 725) | 48.0 (199 574) | −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.01) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 32.7 (157 123) | 35.3 (163 779) | 37.4 (169 983) | 40.6 (173 424) | 42.9 (182 160) | 45.4 (189 007) | 0.11 (0.11 to 0.11) |

| Female breast cancer | 2.8 (13 291) | 2.8 (13 069) | 2.8 (12 594) | 2.8 (12 119) | 2.8 (12 085) | 6.1 (25 298) | 0.15 (0.14 to 0.15) |

| Colorectal cancer | 2.7 (12 806) | 2.7 (12 311) | 2.6 (11 778) | 2.6 (11 002) | 2.5 (10 574) | 4.5 (18 551) | 0.08 (0.08 to 0.09) |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.4 (1888) | 0.4 (1798) | 0.4 (1732) | 0.4 (1638) | 0.4 (1767) | 1.0 (4321) | 0.19 (0.18 to 0.20) |

| Lung cancer | 3.2 (15 485) | 3.3 (15 333) | 3.4 (15 487) | 3.5 (14 759) | 3.4 (14 634) | 4.0 (16 451) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) |

| Prostate cancer | 3.8 (18 140) | 3.9 (17 929) | 3.9 (17 583) | 3.9 (16 475) | 3.8 (16 228) | 5.7 (23 579) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.07) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 32.8 (157 737) | 32.8 (152 267) | 32.3 (147 014) | 32.3 (138 094) | 32.7 (138 966) | 35.8 (148 886) | 0.02 (0.02 to 0.02) |

| Depression | 23.1 (111 105) | 23.8 (110 379) | 25.5 (115 929) | 26.6 (113 660) | 27.6 (117 082) | 31.4 (130 561) | 0.08 (0.08 to 0.08) |

| Diabetes | 39.0 (187 467) | 39.8 (184 595) | 40.3 (183 399) | 41.2 (176 014) | 41.8 (177 340) | 42. 8 (178 315) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.03) |

| Glaucoma | 10.4 (49 887) | 10.1 (47 095) | 10.2 (46 425) | 10.5 (44 907) | 10.4 (44 226) | 10.5 (43 505) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01) |

| Hip or pelvic fracture | 4.9 (23 756) | 5.1 (23 538) | 5.0 (22 606) | 5.1 (21 741) | 5.0 (21 044) | 5.5 (22 942) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.02) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 63.6 (305 493) | 63.0 (292 527) | 62.6 (284 807) | 63.0 (268 742) | 62.3 (264 456) | 62.3 (259 339) | −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.01) |

| Osteoporosis | 19.5 (93 508) | 19.6 (91 198) | 19.9 (90 572) | 20.3 (86 847) | 20.0 (84 758) | 17.2 (71 424) | −0.02 (−0.02 to −0.02) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 34.6 (166 116) | 35.0 (162 267) | 35.6 (162 006) | 37.3 (159 377) | 37.7 (160 118) | 50.5 (210 334) | 0.11 (0.11 to 0.11) |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 15.5 (74 386) | 15.3 (71 101) | 15.2 (69 331) | 15.3 (65 178) | 15.2 (64 387) | 15.2 (63 231) | −0.00 (−0.01 to −0.00) |

The most common conditions treated during index observation stays over the study period were non-specific chest pain (19.3%, 70 151 of 363 037 stays), syncope (5.2%, 18 717 of 363 037 stays), cardiac arrhythmias (4.2%, 15 213 of 363 037 stays), coronary atherosclerosis related diagnoses (4.2%, 15 193 of 363 037 stays), and fluid and electrolyte disorders (3.4%, 12 182 of 363 037 stays). The most common conditions treated during index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays were superficial injury (contusion) (6.6%, 167 882 of 2 540 000 stays), non-specific chest pain (5.6%, 142 874 of 2 540 000 stays), urinary tract infections (3.7%, 93 066 of 2 540 000 stays), abdominal pain (3.3%, 85 047 of 2 540 000 stays), and sprains and strains (3.1%, 77 718 of 2 540 000 stays). The most common conditions treated during index inpatient stays were congestive heart failure (5.4%, 143 521 of 2 667 525 stays), pneumonia (5.1%, 135 792 of 2 667 525 stays), osteoarthritis (4.6%, 121 388 of 2 667 525 stays), cardiac arrhythmias (4.1%, 108 188 of 2 667 525 stays), and septicemia (3.6%, 96 955 of 2 667 525 stays). Table 1 in the web appendix presents the 25 most common conditions treated during index observation stays, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, and inpatient stays during the study period.

Outcomes after index observation stays

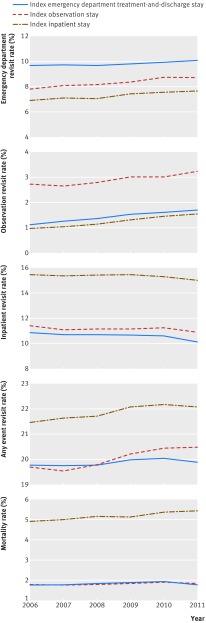

Major adverse outcomes were common in the 30 days after discharge from index observation stays. Averaged over the study period, 8.4% (95% confidence interval 8.3% to 8.4%, 30 312 of 363 037 stays), 2.9% (2.9% to 3.0%, 10 626 of 363 037 stays), and 11.2% (11.1% to 11.3%, 40 491 of 363 037 stays) of index observation stays were followed by an emergency department treatment-and-discharge stay, repeat observation stay, and inpatient stay within 30 days of discharge, respectively. The overall hospital revisit rate including all individual outcomes was 20.1% (19.9% to 20.2%, 72 802 of 363 037 stays) within 30 days of discharge. In total, 49.7% (49.4% to 50.1%, 40 491 of 81 429 stays) of all hospital revisits were for inpatient stays (fig 1). The 30 day mortality was 1.8% (1.8% to 1.9%, 6635 of 363 037 stays). Figure 2 shows 30 day outcomes after index observation stays that have been stratified by year. Over the study period from 2006-11, 30 day rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, repeat observation stays, and any hospital revisit increased (P<0.001 for trend for all outcomes; respective slopes 0.03 (95% confidence interval 0.02 to 0.03), 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05), and 0.01 (0.01 to 0.02)), whereas the 30 day rate of inpatient stays was unchanged (P=0.054 for trend; slope −0.01 (−0.01 to 0.00)). The 30 day mortality rate also did not change from 2006-11 (P=0.091 for trend; slope 0.01 (−0.00 to 0.03)).

Fig 1 Proportion of 30 day revisits for observation stays, emergency department stays, and inpatient stays after discharge from index observation stays, index emergency department stays, and index inpatient stays. Proportions represent average values over study period, 2006-11

Fig 2 30 day outcomes associated with index observation stays, emergency department stays, and inpatient stays by study year

Outcomes after index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays

Adverse outcomes were similar after index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays. Averaged over the study period, 9.8% (95% confidence interval 9.8% to 9.9%, 249 410 of 2 540 000 stays), 1.4% (1.4% to 1.4%, 36 325 of 2 540 000 stays), and 10.6% (10.6% to 10.7%, 269 765 of 2 540 000 stays) of index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays were followed by a repeat emergency department treatment-and-discharge stay, observation stay, and inpatient stay within 30 days of discharge, respectively. The overall hospital revisit rate including all individual outcomes was 19.9% (19.8% to 19.9%, 504 418 of 2 540 000 stays) within 30 days of discharge. Overall, 48.6% (48.4% to 48.7%, 269 765 of 555 500 stays) of all hospital revisits were for inpatient stays (fig 1). The 30 day mortality was 1.8% (1.8% to 1.9%, 46 509 of 2 540 000 stays). Over the study period from 2006-11, 30 day rates of repeat emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, and any hospital revisit increased (P<0.001 for trend for all outcomes; slopes 0.01 (95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.01), 0.08 (0.08 to 0.09), and 0.00 (0.00 to 0.01)) (fig 2), whereas the 30 day rate of inpatient stays decreased (P=0.001 for trend; slope −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.01)) (fig 2). The 30 day mortality increased from 2006-11 (P=0.002 for trend; slope 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01)) (fig 2).

Outcomes after index inpatient stays

Adverse outcomes were highest after index inpatient stays. Averaged over the study period, 7.3% (95% confidence interval 7.2% to 7.3%, 193 887 of 2 667 525 stays), 1.2% (1.2% to 1.2%, 32 851 of 2 667 525 stays), and 15.3% (15.3% to 15.4%, 409 288 of 2 667 525 stays), of index inpatient stays were followed by an emergency department treatment-and-discharge stay, observation stay, and repeat inpatient stay within 30 days of discharge, respectively. The overall hospital revisit rate including all individual outcomes was 21.8% (21.8% to 21.9%, 582 415 of 2 667 525 stays) within 30 days of discharge. Overall, 64.4% (64.2% to 64.5%, 409 288 of 636 026 stays) of all hospital revisits were for inpatient stays (fig 1). The 30 day mortality was 5.2% (5.1% to 5.2%, 137 737 of 2 667 525 stays). Over the study period from 2006-11, 30 day rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, and any hospital revisit increased (P<0.001 for trend for all outcomes; slopes 0.02 (0.02 to 0.03), 0.10 (0.10 to 0.10), and 0.01 (0.01 to 0.01) (fig 2), whereas the 30 day rate of repeat inpatient stays decreased (P=0.001 for trend; slope −0.01 (−0.01 to −0.00)) (fig 2). The 30 day mortality also increased from 2006-11 (P=0.001 for trend; slope 0.02 (0.02 to 0.02)) (fig 2).

Comparative outcomes

Rates of adverse outcomes were similar after discharge from index emergency department stays and index observation stays and highest after discharge from index inpatient stays. Averaged over the study period, 30 day rates of any hospital revisit were 19.9% (504 418 of 2 540 000 stays) and 20.1% (72 802 of 363 037 stays) after discharge from index emergency department stays and index observation stays, respectively, and 21.8% (582 415 of 2 667 525 stays) after discharge from index inpatient stays (differences between index emergency department and observation stays 0.2% (95% confidence interval 0.1% to 0.3%), differences between index emergency department and inpatient stays 2.0% (1.9% to 2.0%), and differences between index observation and inpatient stays 1.8% (1.6% to 1.9%)). The proportion of all hospital revisits that were for inpatient stays was 48.6% (269 765 of 555 500 stays) and 49.7% (40 491 of 81 429 stays) after discharge from index emergency department stays and index observation stays, respectively, and 64.4% (409 288 of 636 026 stays) after discharge from index inpatient stays (differences between index emergency department and observation stays 1.2% (95% confidence interval 0.8% to 1.5%), differences between index emergency department and inpatient stays 15.8% (15.6% to 16.0%), and differences between index observation and inpatient stays 14.6% (14.3% to 15.0%)). Overall, 30 day rates of death were 1.8% (46 509 of 2 540 000 stays) and 1.8% (6 635 of 363 037 stays) after discharge from both index emergency department stays and index observation stays and 5.2% (137 737 of 2 667 525 stays) after index inpatient stays (differences between index emergency department and observation stays 0.0% (95% confidence interval −0.0% to 0.1%), differences between index emergency department and inpatient stays 3.3% (3.3% to 3.4%), and differences between index observation and inpatient stays 3.3% (3.3% to 3.4%)).

Trends over time in revisit outcomes were in most cases similar across care settings. For example, 30 day rates of emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays, observation stays, and any hospital revisit increased over time after discharge from all three care settings (P<0.001 for trend for all). Similarly, rates of inpatient stays decreased after discharge from index emergency department stays and index inpatient stays (P<0.001 for trend for both). Rates of death increased after discharge from index emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays (P=0.002 for trend) and index inpatient stays (P<0.001) but were unchanged after discharge from index observation stays (P=0.091 for trend).

Discussion

We found that one in five observation stays among Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and over in the USA is followed by a hospital revisit within 30 days of discharge. These revisits result in inpatient care in 50% of cases and are increasing over time as observation services become more frequently used as an alternative to short stays in hospital.2 6 20 21 We also found that revisit and mortality rates after discharge from observation stays closely parallel outcomes after discharge from the emergency department. Taken together, these results suggest that older adults discharged from observation stays are vulnerable to major adverse events at rates that closely parallel emergency department discharges. Yet in contrast with both emergency department and hospital inpatient care,30 31 41 outcomes after observation services have not been a major focus for care improvement by clinicians, hospitals, or payers.

Our findings extend previous work describing the vulnerability experienced by patients discharged from observation stays. Firstly, we found that revisit rates among Medicare beneficiaries nationally are approximately 20% higher than expected when compared with the results of a previous study of 3509 consecutively enrolled patients of all ages cared for in the dedicated observation unit of one academic center in 2002.18 Although another study involving 340 older patients discharged after observation stays from 1996-2000 found similar revisit rates to ours, the observation stays in this study were unlikely to be broadly representative, as they were purposefully sampled to include the same admitting diagnoses as in a comparator group of patients who were younger.19 Secondly, we showed for the first time that 30 day revisit rates are increasing over time in tandem with the complexity of patients receiving observation services, suggesting that patients who are older and discharged from observation stays will continue to remain at risk for major adverse outcomes for the foreseeable future. Thirdly, we found that rates of adverse outcomes are similar after discharge from emergency department stays and observation stays. This result may surprise those who expect revisit and mortality rates after discharge from observation services to be intermediate between corresponding revisit and mortality rates after discharge from emergency department and inpatient stays. This finding may relate to our decision to categorize patients ultimately admitted for inpatient care after receipt of observation services as inpatient stays rather than observation stays. We did this intentionally, as our aim was to determine outcomes after discharge from observation stays to better understand post-hospital vulnerability and the potential benefits of improved transitional care for this population. Our findings may also relate to the largely discretionary use of observation services in practice within and across hospitals.42 As a result, it may be that many patients treated and discharged after observation stays have similar illness acuity to patients discharged from the emergency department.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

This study has several strengths. Firstly, it utilized nationally representative Medicare data, which should result in generalizable estimates of revisit rates and mortality rates after discharge from observation stays. These estimates showed higher than expected revisit rates compared with previous work.18 Medicare data also permit robust outcomes assessment with no loss to follow-up, as Medicare is the payer for all older adults in the USA. Secondly, the study simultaneously examined multiple health outcomes over time for three different categories of index hospital stays, which afforded unique insights. For example, we found that revisit rates after discharge from observation stays are increasing over time in tandem with the comorbidity burden of patients receiving observation services, suggesting that the rising use of observation stays as a substitute for short stays in hospital in the USA may further increase vulnerability in this population over time. We also found that revisit rates and mortality rates after discharge from observation stays most closely resemble corresponding outcomes after discharge from the emergency department; revisit rates and mortality rates after inpatient stays are considerably higher.

Results should also be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. Firstly, data were restricted to adults aged 65 years and over, so results may not apply to patients who are younger and receiving observation services. However, older Americans experience more than one million observation stays each year,2 indicating that our findings have implications for a substantial number of patients. Outcomes after observation stays are also a topic of growing relevance for European countries, including the UK, based on data showing that short periods of observation can improve patient satisfaction and triage decisions while reducing unnecessary short stays in hospital.43 44 Organizations such as the National Health Service, College of Emergency Medicine, Nuffield Trust, and other specialty societies have promoted the use of this treatment strategy to improve outcomes and help tackle inpatient bed constraints.45 46 47 48 49 50 Indeed, the proportion of UK hospitals with observation wards has increased over time, with almost 50% of facilities reporting that they have a dedicated observation ward or clinical decision unit that is capable of seeing patients with a range of presenting conditions.46 Secondly, the study does not report other outcomes that may be important to patients who are older following observation stays, including symptoms, function, and quality of life, as this information is not available within the administrative data used in our study. Administrative data also cannot identify the proportion of revisits that resulted from suboptimal quality of care, the exact location (eg, emergency department, dedicated hospital observation unit, or hospital inpatient setting) in which each observation stay occurred, or whether another type of admission (eg, emergency department treatment-and-discharge stays or inpatient stays) would have produced better health outcomes. Thirdly, the study does not adjust revisit and mortality outcomes for case mix severity. In the USA, hospitals are under pressure to identify and code comorbidities for inpatient stays, as patient complexity influences payment.51 52 In contrast, hospitals have little financial incentive to identify comorbidities for emergency department stays and observation stays.53 54 Adjustment of post-discharge outcomes for patient comorbidities could therefore introduce bias by making patients who require inpatient hospital stays appear particularly sick due to the higher prevalence of coded comorbid conditions. Our unadjusted outcomes make clear that revisits after discharge from observation stays are common, frequently result in inpatient stays, and are increasing over time.

Implications for clinical practice and research

Our findings have implications for clinical practice and research. Revisit rates of 20% after observation stays suggest that patients who are older and receiving observation services are vulnerable to major adverse outcomes after discharge and may benefit from improved transitional and post-acute care. To date, focus on care transitions, post-hospital outpatient care, and corresponding outcomes in the USA has largely been applied to vulnerable older adults discharged from inpatient stays23 55 56 57 58 and to a smaller extent, emergency department stays.22 34 41 Little attention has been directed to improving outcomes after observation services. Our results suggest that strategies designed to integrate care for patients after discharge from emergency department stays and inpatient stays, such as facilitating access to outpatientproviders,59 early and longitudinal follow-up,56 60 61 timely transmittal of information from hospitals to outpatient teams,62 outpatient availability of care management services,62 63 multidisciplinary team based care,64 65 and home visits66 may also warrant consideration for patients after observation stays, as greater than 90% are discharged home.67 The potential importance of these strategies has likely grown over time as patient complexity and vulnerability have increased. Further research is needed to examine the utility of these interventions following discharge from observation services, as well as their prioritization. However, as revisit and mortality outcomes are most similar after discharge from emergency department stays and observation stays, application of lessons learnt from the emergency department context may be the most reasonable starting point. Research is also needed to better understand if observation stays should be an increasing focus of quality improvement for government. To answer this question, data are needed on the variability in observation stay outcomes across hospitals and a better understanding of how suboptimal transitional and post-acute care may be contributing to revisit rates.

Conclusions

Hospital revisits are common in the month after discharge from observation stays, frequently result in inpatient hospitalizations, and are increasing over time among American Medicare beneficiaries. While outcomes after discharge from emergency department stays and hospital inpatient stays have been a focus of clinical care, policy, and research, parallel outcomes after discharge observation stays have received little attention. As observation stays become increasingly used as an alternative to short stay hospitalizations, further awareness of the quality of care and results associated with observation services may identify opportunities to improve outcomes for patients.

What is already known on this topic

Outpatient observation services are increasingly used in the USA as a substitute for short stays in hospital

30 day outcomes including hospital revisits and death for the more than one million patients aged 65 years or more receiving care in this setting are unknown

What this study adds

Hospital revisits are common after discharge from observation stays, frequently result in inpatient hospital stays, and have increased over time among Medicare beneficiaries in the USA

Hospital revisit rates are similar after emergency department and observation stays

Strategies shown to enhance care transitions from the emergency department may be reasonable starting points to improve post-observation outcomes

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Appendix: Supplementary information

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; to drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and to approving the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. KD and AKV are guarantors of the paper and accept full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: KD is supported by grant K23AG048331 from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B Beeson career development award program. He is also supported by grant P30AG021342 from the Yale Claude D Pepper Older Americans Independence Center. NRD, ESS, and HMK are supported by grant K12HS023000 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AKV is supported by an Emergency Medicine Foundation health policy grant to study emergency department and hospital utilization by Medicare beneficiaries and by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid innovation transforming clinical practice initiative (contract 1L1CMS333479-01-00) for work seeking to improve the use of observation stays and inpatient hospital stays for chest pain. At the time this research was initially performed, AKV was also supported by an Emergency Medicine Foundation health policy scholar award and by CTSA grant UL1TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the American Federation for Aging Research, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or the National Quality Forum. The funders did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: KD, LQ, ZL, NRD, ESS, HMK, and AKV work under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures, as did MB at the time this research was performed. KD is a consultant for and member of a scientific advisory board for Clover Health, a Medicare preferred provider organization. He is also a member of the Standing Cardiovascular Committee of the National Quality Forum. HMK is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth and is the recipient of research grants from Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson through Yale University. AKV is a member of the Standing Health and Well Being Committee of the National Quality Forum.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee (institutional review board) at Yale University.

Data sharing: No additional data are available due to data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. SAS code used in programming or analysis can be made freely available to others.

Transparency: The manuscript’s guarantors (KD and AKV) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Department of Health & Human Services. CMS Manual System Pub 100-02 Medicare Benefit Policy, Transmittal 42, December 16, 2005. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/r42bp.pdf.

- 2.Office of Inspector General, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Hospitals’ use of observation stays and short inpatient stays for Medicare beneficiaries, OEI-02-12-00040. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-12-00040.pdf.

- 3.Robin DW, Gershwin RJ. RAC attack--Medicare Recovery Audit Contractors: what geriatricians need to know. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1576-8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02974.x pmid:20662954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison JP, Barksdale RM. The impact of RAC audits on US hospitals. J Health Care Finance 2013;39:1-14.pmid:24003757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Recovery Audit Program. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/monitoring-programs/medicare-ffs-compliance-programs/recovery-audit-program/.

- 6.Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1251-9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129 pmid:22665837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao L, Schur C, Kowlessar N, Lind KD. Rapid Growth in Medicare Hospital Observation Services: What’s Going On? AARP Public Policy Institute Report No. 2013-10. September 2013. http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/health/2013/rapid-growth-in-medicare-hospital-observation-services-AARP-ppi-health.pdf.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What's Medicare? https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/decide-how-to-get-medicare/whats-medicare/what-is-medicare.html.

- 9.Wikipedia. Medicare (United States). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medicare_(United_States).

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Methods Series. Identifying Observation Services in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Databases, Report #2015-05. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2015-05_public.pdf.

- 11.Medicare Rights Center. Differences between Original Medicare and Medicare Advantage Plans. http://www.medicarerights.org/fliers/Medicare-Advantage/Differences-Between-OM-and-MA.pdf?nrd=1.

- 12.Kaiser Health News. FAQ: hospital observation care can be costly for Medicare patients. http://khn.org/news/observation-care-faq/.

- 13.Penumetsa SC, Mallidi J, Friderici JL, Hiser W, Rothberg MB. Outcomes of patients admitted for observation of chest pain. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:873-7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.940 pmid:22566486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbass IM, Virani SS, Michael Swint J, Chan W, Franzini L. One-year outcomes associated with using observation services in triaging patients with nonspecific chest pain. Clin Cardiol 2014;37:591-6. 10.1002/clc.22319 pmid:25113151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbass I. Variability in the initial costs of care and one-year outcomes of observation services. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:395-400. 10.5811/westjem.2015.2.24281 pmid:25987913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cafardi SG, Pines JM, Deb P, Powers CA, Shrank WH. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:16-9. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049 pmid:26490388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrager J, Wheatley M, Georgiopoulou V, et al. Favorable bed utilization and readmission rates for emergency department observation unit heart failure patients. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:554-61. 10.1111/acem.12147 pmid:23758301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross MA, Hemphill RR, Abramson J, Schwab K, Clark C. The recidivism characteristics of an emergency department observation unit. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:34-41. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.02.012 pmid:20303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross MA, Compton S, Richardson D, Jones R, Nittis T, Wilson A. The use and effectiveness of an emergency department observation unit for elderly patients. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:668-77. 10.1067/mem.2003.153 pmid:12712034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright B, O’Shea AM, Ayyagari P, Ugwi PG, Kaboli P, Vaughan Sarrazin M. Observation Rates At Veterans’ Hospitals More Than Doubled During 2005-13, Similar To Medicare Trends. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1730-7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1474 pmid:26438750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venkatesh AK, Geisler BP, Gibson Chambers JJ, Baugh CW, Bohan JS, Schuur JD. Use of observation care in US emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS One 2011;6:e24326 10.1371/journal.pone.0024326 pmid:21935398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duseja R, Bardach NS, Lin GA, et al. Revisit rates and associated costs after an emergency department encounter: a multistate analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:750-6. 10.7326/M14-1616 pmid:26030633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418-28. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 pmid:19339721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355-63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476 pmid:23340637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Kulkarni VT, et al. Trajectories of risk after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2015;350:h411 10.1136/bmj.h411 pmid:25656852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuur JD, Hsia RY, Burstin H, Schull MJ, Pines JM. Quality measurement in the emergency department: past and future. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:2129-38. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0730 pmid:24301396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkatesh A, Goodrich K, Conway PH. Opportunities for quality measurement to improve the value of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions. Ann Intern Med 2014;161(Suppl):S76-80. 10.7326/M13-3014 pmid:25402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html.

- 29.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS roadmaps overview. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/downloads/RoadmapOverview_OEA_1-16.pdf.

- 30.Kocher RP, Adashi EY. Hospital readmissions and the Affordable Care Act: paying for coordinated quality care. JAMA 2011;306:1794-5. 10.1001/jama.2011.1561 pmid:22028355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare Program; Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment Systems for Acute Care Hospitals and the Long-Term Care Hospital Prospective Payment System Policy Changes and Fiscal Year 2016 Rates; Revisions of Quality Reporting Requirements for Specific Providers, Including Changes Related to the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program; Extensions of the Medicare-Dependent, Small Rural Hospital Program and the Low-Volume Payment Adjustment for Hospitals. Final rule; interim final rule with comment period. Fed Regist 2015;80:49325-886.pmid:26292371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Standard analytical files. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/IdentifiableDataFiles/StandardAnalyticalFiles.html.

- 33.Venkatesh AK, Mei H, Kocher K, et al. Identification of Emergency Department Visits in Medicare Administrative Claims: Approaches and Implications. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:422-31.pmid:27864915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabbatini AK, Kocher KE, Basu A, Hsia RY. In-Hospital Outcomes and Costs Among Patients Hospitalized During a Return Visit to the Emergency Department. JAMA 2016;315:663-71. 10.1001/jama.2016.0649 pmid:26881369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cubanski J, Neuman P. Medicare doesn’t work as well for younger, disabled beneficiaries as it does for older enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1725-33. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0962 pmid:20705670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 37.Gabayan GZ, Derose SF, Asch SM, et al. Patterns and predictors of short-term death after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:551-558.e2. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.001 pmid:21802775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabayan GZ, Asch SM, Hsia RY, et al. Factors associated with short-term bounce-back admissions after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med 2013;62:136-144.e1. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.01.017 pmid:23465554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabayan GZ, Sarkisian CA, Liang LJ, Sun BC. Predictors of admission after emergency department discharge in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:39-45. 10.1111/jgs.13185 pmid:25537073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraham J. Computation of CIs for Binomial proportions in SAS and its practical difficulties. PhUSE 2013, Paper SP05. http://www.lexjansen.com/phuse/2013/sp/SP05.pdf.

- 41.American College of Emergency Physicians Transitions of Care Task Force. Transitions of care task force report, September 2012. https://www.acep.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=91206.

- 42.Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. Med Care 2016;54:1070-7. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 pmid:27579906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooke MW, Higgins J, Kidd P. Use of emergency observation and assessment wards: a systematic literature review. Emerg Med J 2003;20:138-42. 10.1136/emj.20.2.138 pmid:12642526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misch F, Messmer AS, Nickel CH, et al. Impact of observation on disposition of elderly patients presenting to emergency departments with non-specific complaints. PLoS One 2014;9:e98097 10.1371/journal.pone.0098097 pmid:24871340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.England NHS. High quality care for all, now and for future generations: Transforming urgent and emergency services in England. The evidence base from the urgent and emergency care review. June 2013. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/urg-emerg-care-ev-bse.pdf.

- 46.College of Emergency Medicine. The drive for quality. How to achieve safe, sustainable care in our emergency departments? System benchmarks and recommendations. May 2013. https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/Policy/CEM7030-CEM-Full-report---The-drive-for-quality---System-benchmarks-and-recommendations.pdf.

- 47.Nuffield Trust. NHS hospitals under pressure: trends in acute activity up to 2022. October 2014. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/nhs-hospitals-under-pressure-trends-in-acute-activity-up-to-2022.

- 48.Kenny RA, Brignole M, Dan GA, et al. Syncope Unit: rationale and requirement--the European Heart Rhythm Association position statement endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2015;17:1325-40. 10.1093/europace/euv115 pmid:26108809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miró Ò, Peacock FW, McMurray JJ, et al. Acute Heart Failure Study Group of the ESC Acute Cardiovascular Care Association. European Society of Cardiology - Acute Cardiovascular Care Association position paper on safe discharge of acute heart failure patients from the emergency department. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016; pii:2048872616633853.pmid:26900163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purdy S. The King’s Fund. Avoiding Hospital Admissions, What Does the Research Evidence Say? December 2010. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Avoiding-Hospital-Admissions-Sarah-Purdy-December2010.pdf.

- 51.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Acute inpatient PPS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html?redirect=/AcuteinpatientPPS/.

- 52.e-MedTools. MCC and CC List for CMS MS-DRG. https://e-medtools.com/drg_modifier.html.

- 53.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital outpatient PPS. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalOutpatientPPS/index.html.

- 54.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program: Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems and Quality Reporting Programs; Organ Procurement Organization Reporting and Communication; Transplant Outcome Measures and Documentation Requirements; Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Programs; Payment to Nonexcepted Off-Campus ProviderBased Department of a Hospital; Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program; Establishment of Payment Rates Under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for Nonexcepted Items and Services Furnished by an Off-Campus ProviderBased Department of a Hospital. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-11-14/pdf/2016-26515.pdf. [PubMed]

- 55.Kociol RD, Peterson ED, Hammill BG, et al. National survey of hospital strategies to reduce heart failure readmissions: findings from the Get With the Guidelines-Heart Failure registry. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:680-7. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967406 pmid:22933525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2010;303:1716-22. 10.1001/jama.2010.533 pmid:20442387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:444-50. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000101 pmid:23861483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bradley EH, Sipsma H, Horwitz LI, et al. Hospital strategy uptake and reductions in unplanned readmission rates for patients with heart failure: a prospective study. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:605-11. 10.1007/s11606-014-3105-5 pmid:25523470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rising KL, Padrez KA, O’Brien M, Hollander JE, Carr BG, Shea JA. Return visits to the emergency department: the patient perspective. Ann Emerg Med 2015;65:377-386.e3. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.015 pmid:25193597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:999-1006. 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005 pmid:8185149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:675-84. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x pmid:15086645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, Pines JM. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:12-23.e1. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.025 pmid:22542309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guttman A, Afilalo M, Guttman R, et al. An emergency department-based nurse discharge coordinator for elder patients: does it make a difference?Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:1318-27.pmid:15576523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1190-5. 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806 pmid:7565975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sochalski J, Jaarsma T, Krumholz HM, et al. What works in chronic care management: the case of heart failure. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:179-89. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.179 pmid:19124869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:774-84. 10.7326/M14-0083 pmid:24862840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feng Z, Jung HY, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care 2014;52:796-800. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 pmid:25054826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Supplementary information