Abstract

In the present article, based on results from a survey study in Sweden among 2,355 cancer patients, the role of religion in coping is discussed. The survey study, in turn, was based on earlier findings from a qualitative study of cancer patients in Sweden. The purpose of the present survey study was to determine to what extent results obtained in the qualitative study can be applied to a wider population of cancer patients in Sweden. The present study shows that use of religious coping methods is infrequent among cancer patients in Sweden. Besides the two methods that are ranked in 12th and 13th place, that is, in the middle (Listening to religious music and Praying to God to make things better), the other religious coping methods receive the lowest rankings, showing how nonsignificant such methods are in coping with cancer in Sweden. However, the question of who turns to God and who is self-reliant in a critical situation is too complicated to be resolved solely in terms of the strength of individuals’ religious commitments. In addition to background and situational factors, the culture in which the individual was socialized is an important factor. Regarding the influence of background variables, the present results show that gender, age, and area of upbringing played an important role in almost all of the religious coping methods our respondents used. In general, people in the oldest age-group, women, and people raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average use of religious coping methods than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Keywords: religious coping, spiritual-oriented coping, cancer, culture

Introduction

Background

The various ways in which individuals cope with illnesses have been of interest in health research. A relatively new line of interest in this research area is in the role of religion, spirituality, and existential issues in coping. Some studies have looked at the role of religiosity and spirituality in disease treatment (Koenig, King, & Carson, 2012; Padela & Curlin, 2012; Phelps et al., 2009; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006), while others have objected the efforts to integrate religion into clinical practice and pointed out the lack of scientific evidence concerning the effectiveness of religious method in comparison with other coping methods (Poole & Higgo, 2010; Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003; Sloan, 2006; Sloan, Bagiella, & Powell, 2001; Sloan et al., 2000). However, a great deal of the research on religious and spiritually oriented coping has been carried out in the United States, where religion is an integral part of many people’s lives, whereas the situation in Europe and other parts of the world is somewhat different (Hvidtjørn, Hjelmborg, Skytthe, Christensen, & Hvidt, 2014; LaCour & Hvidt, 2010). Nonetheless, studies on religious coping in Europe have tended to focus on religious people (Alma, 1998; Gall, Migues de Renartat, & Boonstra, 2000; Hvidt, 2007, 2008; Torbjørnsen, Stifoss-Hanssen, Abrahamsen, & Hannisdal, 2000). In recent years, however, the attention has turned to secular society and secular people facing various crises (LaCour & Hvidt, 2010).

Research on religious and spiritual coping has rarely examined in detail in patients who either are uninterested in institutional religiosity but follow their own spiritual paths or who express no interest at all in spirituality and religiosity. In a qualitative study of 51 cancer patients in Sweden, where most people do not consider themselves religious,1 the use of religious and spiritually oriented coping strategies was investigated in a primarily secular context (Ahmadi, 2006).

The starting point of the study was Kenneth I. Pargament’s (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000) The Many Methods of Religious Coping (RCOPE)2 questionnaire, which examines the full range of religious coping methods. The qualitative study revealed the impact of culture and ways of thinking on use of the RCOPE methods in the face of the stressors caused by cancer. In this regard, a tendency toward rationalism, pragmatism, individualism, and spirituality, as opposed to religiosity, was found to have influenced Swedish informants’ choice of religious coping methods.

Based on the results of the previously mentioned qualitative study, a survey study was carried out to determine the extent to which these results could be applied to a wider population of cancer patients in Sweden. In other words, the quantitative study was aimed to study the prevalence of the results of the qualitative study.

The RCOPE questionnaire and questions inspired by the previously mentioned qualitative study were used in designing the survey.

RCOPE

Although the present investigation is based on a previous qualitative study, the established religious and spiritually oriented methods revealed in other studies—qualitative and quantitative—were also taken into account. Results were compared with RCOPE. RCOPE was chosen because it is based on theoretical and empirical studies, includes many of the religious coping methods shown in other studies, and has been tested in a large sample of different groups of informants.

Five fundamental religious functions constitute the basis of RCOPE (Pargament et al., 2000, p. 521):

Meaning. According to theorists like Geertz (1966), religion plays a key role in people’s search for meaning. In the face of suffering and inexplicable life experiences, religion offers frameworks that enable understanding and interpretation.

Control. Other theorists, such as Fromm (1950), have emphasized the role of religion in the search for control. Confronted with events for which the individual has no or few resources, religion offers many ways to achieve a sense of mastery and control.

Comfort/Spirituality. According to the traditional Freudian (1961) view, religion is meant to reduce the individual’s anxiety about living in a world where calamity can strike at any time. Yet, it is difficult to distinguish comfort-oriented religious coping strategies from methods that may have a spiritual function that is genuine. From a religious perspective, spirituality, or the wish to connect with a force beyond the individual, is the most fundamental function of religion (Johnson, 1959).

Intimacy/Spirituality. Sociologists such as Durkheim (1915) have generally stressed the role of religion in facilitating social cohesion. Religion is said to be a mechanism that promotes social solidarity and social identity. However, intimacy with others is often encouraged through spiritual methods, such as offering spiritual help to others and the spiritual support provided by the clergy or congregation members. Thus, once again, ‘it is difficult to separate out many of the methods that foster intimacy from methods that foster closeness with a higher power’ (Buber, 1970).

Life transformation. Theorists have traditionally seen religion as being conservational in nature—as helping people uphold meaning, control, comfort, intimacy, and closeness to God. However, religion also may help people make major life transformations, that is, by relinquishing old objects of value and finding new sources of significance (Pargament, 1997).”

Pargament et al. (2000, pp. 522–524) defined a number of religious and spiritually oriented methods, both potentially helpful and potentially harmful methods, with respect to each of these five fundamental religious functions.

Definition of Religion and Spirituality

Zinnbauer and Pargament (2005) proposed two alternative definitions of religion and spirituality. Both scholars have criticized modern approaches that polarize religion and spirituality, and both scholars have stressed that definitions of religion and spirituality must be embedded in a context that can be used to differentiate between the two constructs. According to both Zinnbauer and Pargament, the search for the sacred is an important component of religion and spirituality. But while Zinnbauer and Pargament (2005, pp. 35–36) suggested that “spirituality is the broader construct,” Pargament regarded religiousness as the broader of the two (1997, pp. 36–37). In Pargament’s (1997) view, spirituality involves a search for the sacred, while religiousness involves a search for significance in ways that are related to the sacred. In contrast, Zinnbauer and Pargament (2005) defined spirituality as a personal or group search for the sacred and religiousness as a personal or group search for the sacred that develops within a traditional sacred context.

The present study employs the definition of religion and spirituality suggested by Ahmadi (2006), who, in turn, made use of Jenkins and Pargament’s (1995, p. 52) definition. According to Ahmadi (2006), religiousness is,

A search for significance that unfolds within a traditional sacred context. It is then related to an organized system of belief and practice relating to a sacred source that includes individual and institutional expressions, serves a variety of purposes, and may play potentially helpful and/or harmful roles in people’s lives. (pp. 71–71)

The earlier definition limits the search for significance to the framework of a traditional sacred context, as does Zinnbauer and Pargament’s definition (2005, pp. 35–36); it also reflects the spirit of our time, which objects to traditional authority and institutional expressions of belief. Ahmadi’s (2006) definition, in contrast to Zinnbauer, Pargamnet, and Scott (1999, p. 909), allows communication with the general public owing to its sensitivity to the ways in which people identify themselves in cultural settings where spirituality is more prominent than religiosity.

Defining spirituality is more difficult. It cannot be put into a box. Still, a working definition was required to conduct the present study. A definition based partly on Ahmadi’s (2006) work and partly on Jenkins and Pargament’s (1995, pp. 52–53) definition was suggested. Ahmadi (2006) defined spirituality as,

A search for connectedness with a sacred source that is related or not related to God or any religious holy sources. Spirituality involves efforts to consider metaphysical or transcendent aspects of everyday life as they relate to forces, transcendent and otherwise. Hence, spirituality encompasses religion as well as many beliefs and practices from outside the normally defined religious sphere. (pp. 72–73)

Thus, in the present study, the term spirituality will refer to the kind of spirituality that can be experienced without faith, myths, legends, founding superpersonalities, and superstition and that can be practiced both in a religious context and outside the religious sphere. For individuals socialized in a secular and rationally organized society such as Sweden, where people are thought to be irreligious, it may be nearly impossible to accept as truth many aspects of conventional religions, such as the mythology and legends of superpersonalities and various superstitions. It goes without saying that we are not dealing with people who have a strong faith.3 Because many aspects of religion are established as theistic, conventional religions are difficult to accept. To accept them, the individual must make a concerted effort to overcome rational, logical thought. For this reason, we chose a definition of spirituality focused on a kind of spirituality that is experienced both within a religious context and outside the religious sphere. This definition stresses the higher aspects of human life and refers to individuals who go beyond the banality of everyday existence and experience a transcendent view of life.

Based on the results from a survey study in Sweden among cancer patients, the present article discusses the role of religion in coping. In doing this, only the results concerning religious coping in Sweden are under focus; findings on other meaning-making coping methods, for example, spiritual coping or secular existential coping, will be presented in a separate article.

Methodology

The data were collected by SKOP,4 a professional data acquisition agency. SKOP made use of several cancer organizations, for example, The Swedish Union for Ileostomy, Colostomy, and Urostomy Operated Persons (ILCO), The Leukemia Patients Organization (Bloodcancerförbundet) in Stockholm, and The Breast Cancer National Organization (BRO). The great majority of respondents (61%) were found on the BRO’s membership register, a fifth (19%) on the leukemia association’s register, and a fifth (20%) on the ILCO organization’s register. The survey was conducted as a postal questionnaire. No reminder letters were sent out. Data collection was carried out during the period March to May 2011.

Although recruiting informants via cancer organizations may raise some concerns, such as representativeness, this approach was considered the most appropriate, given the ethical considerations involved when recruiting a vulnerable group of study participants such as cancer patients.

Five thousand questionnaires were sent randomly to persons diagnosed with cancer in Sweden. Of these recipients, 62 were either supporting members or were deceased or suffered from dementia, and 47 questionnaires were returned for unknown reasons. Thus, the resulting sample was 4,891 persons. Of these, 2,417 questionnaires were returned, giving a response rate of 49%. Despite this relatively low response rate, the attrition rate in the study is not considered high, as similar studies on seriously ill individuals have shown very high dropout rates (Shih, 2002; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Information (Percent).

| Sex |

Age (year) |

Education (year) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | −59 | 60–69 | 70+ | −9 | 10–12 | 13+ without degree | Academic degree |

| 79 | 21 | 29 | 38 | 33 | 33 | 28 | 17 | 22 |

According to Swedish research ethics principles, researchers are not allowed (except in special cases) to pose any questions on informants’ religious affiliation. Therefore, the present study lacks background information on religion or faith. However, we were able to include information on informants’ beliefs in a personal God or a higher life-giving force. Results regarding this question will be presented later on in the article.

Results and Analysis

Religiosity/Spirituality

In response to the question “Do you believe in God?” almost half (49%) of our respondents answered in the affirmative. A large proportion of them belonged to the oldest age-group: 70 years or older. Among women and among those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer inhabitants, more persons reported believing in God compared with respondents in the younger groups, men, and those raised in larger towns. Those reporting that they did not believe in God were asked to answer the follow-up question “Do you think there is a higher power or life-giving force?” Forty-five percent of those who did not believe in God reported believing in a higher power or life-giving force. One in four respondents (25%) reported that they had no faith.

Almost half (45%) of our respondents believed in life after death. A greater proportion of individuals in the youngest age-group (59 years or younger), of the women, and of those raised in a place with 20,000 or fewer residents reported believing in life after death, as compared with older people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Almost one fifth (18%) of respondents believed in reincarnation. A greater proportion of individuals in the youngest age-group, of women, and of those with a recent diagnosis reported believing in reincarnation compared with older people, men, and those with an older diagnosis.5

In contrast, the population of cancer patients studied here showed greater tendencies toward religiosity than the whole population of Sweden did, perhaps owing to differences in the age distribution. In the present study, only slightly less than one third (29%) of respondents were 59 years old or younger. The largest proportion of respondents (38%) were between 60 and 69 years, while one third (33%) were 70 years or older.

Religious Coping

In the present study, respondents were asked to reflect on whether 24 different items helped them feel better when they experienced stress, sadness, or depression during or after their illness. For each factor, there were four alternatives: The factor in question helped them not at all, to a small extent, to quite a large extent, or to a very large extent. A numerical scale was used, where 1 was not at all and 4 to a very large extent.

Questions concerning religious coping focused on the following methods:

Praying to God to make things better

Thinking that you have done your best and now only God is in control

Thinking about God or the life of Jesus or other religious people’s lives

Thinking that you have ever had a sense of a strong connection with God

Going to church

Listening to religious music

Seeking spiritual help from a priest or other religious leader

All of the earlier methods are RCOPE methods. Another method exists that is called “Trying to control your situation without God’s help” and that refers to Self-Directing Religious Coping, which is one of the religious methods in the group Coping to Gain Control (Pargament et al., 2000, pp. 522–524). Using this method, the individual seeks control directly through his or her own initiative rather than seeking help from God. As Ahmadi (2006, p. 37) suggested, the efforts of a person who gains control through her or his own initiative rather than by leaning on God can hardly be classified as religious coping methods (a point that will be discussed later). For this reason, we have chosen not to discuss this method in this section.

Before presenting our findings on the RCOPE methods, it should be mentioned that we have used diagrams to present the effect of background factors. As the results show, overall, three factors have been important across all coping strategies: age, gender, and area of upbringing. Thus, we have confined ourselves to primarily reporting the impact of these factors. In some cases, however, class belonging or other factors also played a significant role. In such cases, these factors have been added to our presentation of background factors.

Praying to God to make things better

As seen in Table 2, the factor “Praying to God to make things better” is in 13th place (M = 1.7). One fifth of respondents (20%) reported that this factor had helped them feel better during or after their illness to a large or quite a large extent, one in 20 (6%) reported that this method had helped them to a large extent, and one in five (21%) reported that it had helped them only marginally. Nearly three in five (58%) chose the option not at all.

Table 2.

When You Have Felt Stressed, Sad, or Depressed During or After Your Illness, to What Extent Have the Following Helped You Feel Better?

| June 2011 | Percentage that answers |

M | Number of answers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all (1) | Small (2) | Quite large (3) | Very large (4) | |||

| Thinking about God or contemplating the life of Jesus or other religious personages? | 63 | 20 | 12 | 6 | 1.6 | 2,266 |

| Thinking about a spiritual power? | 49 | 23 | 18 | 9 | 1.9 | 2,264 |

| Going to church? | 64 | 21 | 10 | 4 | 1.5 | 2,261 |

| Praying? | 51 | 20 | 17 | 12 | 1.9 | 2,320 |

| Listening to religious music? | 65 | 20 | 11 | 3 | 1.5 | 2,245 |

| Listening to spiritual music? | 56 | 23 | 16 | 5 | 1.7 | 2,267 |

| Listening to the music of Nature (birdsong and the whistling of the wind)? | 13 | 21 | 38 | 28 | 2.8 | 2,335 |

| Going for walks or doing other outdoor activities which give you a sense of spirituality? | 19 | 18 | 34 | 29 | 2.7 | 2,338 |

| Thinking and contemplating the meaning of life and other things, in solitude? | 32 | 36 | 26 | 6 | 2.1 | 2,307 |

| Helping others to experience spirituality? | 50 | 28 | 19 | 3 | 1.8 | 2,282 |

| Thinking that you have done your best and the rest is in God’s hands? | 62 | 18 | 13 | 7 | 1.6 | 2,310 |

| Praying to God that He will make things better? | 58 | 21 | 14 | 6 | 1.7 | 2,302 |

| Trying to control your situation without God’s help? | 30 | 20 | 34 | 15 | 2.3 | 2,283 |

| Trying to stop thinking about your illness by thinking of spiritual matters? | 64 | 25 | 9 | 2 | 1.5 | 2,327 |

| Seeking spiritual help from a priest or other religious leaders? | 86 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1.2 | 2,301 |

| Providing spiritual support to others? | 77 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 1.3 | 2,290 |

| Having sometime experienced a strong connection to God? | 66 | 16 | 12 | 6 | 1.6 | 2,324 |

| Having experienced a strong spiritual connection to other people? | 57 | 24 | 15 | 4 | 1.7 | 2,296 |

| Have you ever believed that your life is part of something greater and higher? | 38 | 27 | 22 | 12 | 2.1 | 2,323 |

| Having experienced a strong sense of spirituality? | 54 | 23 | 16 | 8 | 1.8 | 2,314 |

| Believing or feeling that there is a spiritual power within you that helps you cope with your problems? | 46 | 24 | 20 | 9 | 1.9 | 2,341 |

| Hoping for a spiritual rebirth in this world? | 75 | 17 | 6 | 2 | 1.3 | 2,285 |

| Preferring to be alone, thinking about your life or contemplating life, to feel better? | 43 | 32 | 21 | 4 | 1.9 | 2,304 |

| That Nature is an important resource to help you cope with your illness? | 11 | 20 | 38 | 30 | 2.9 | 2,362 |

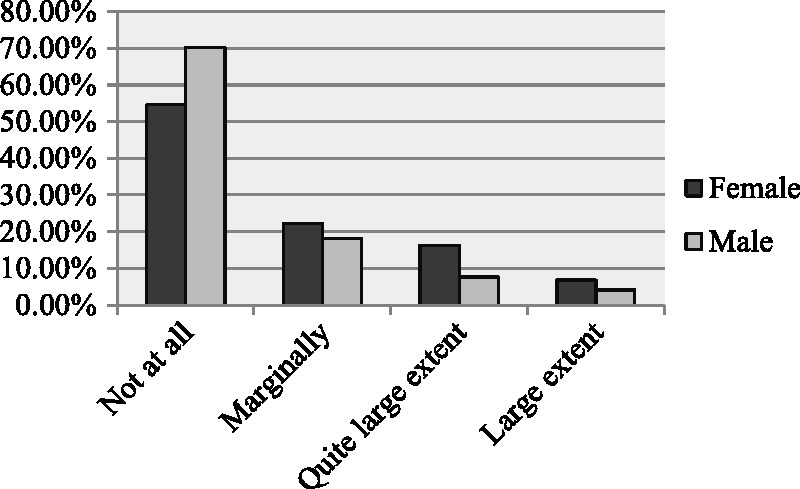

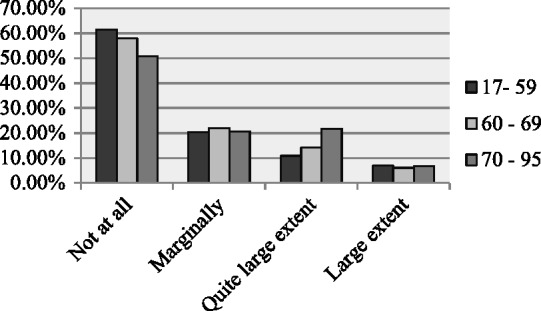

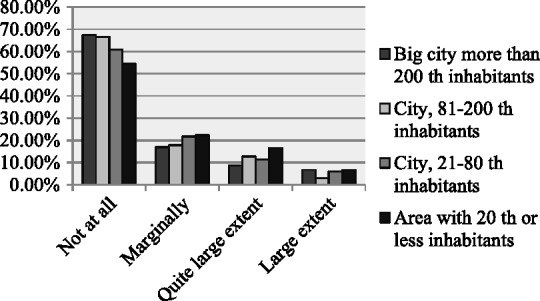

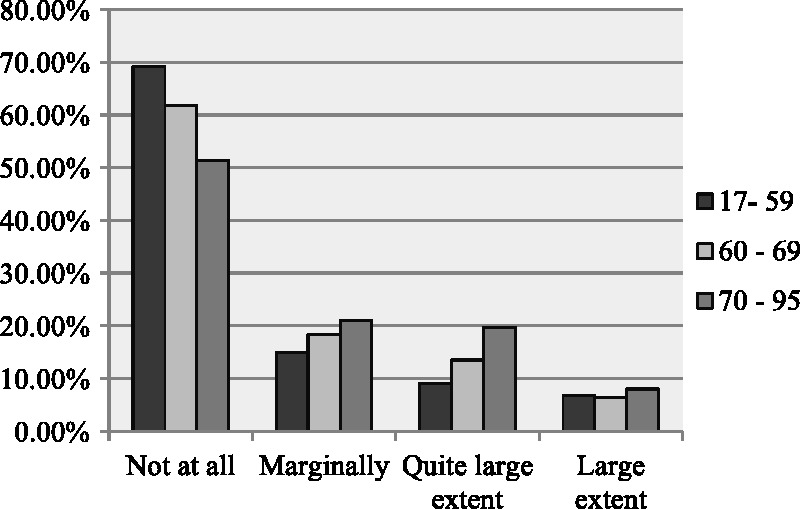

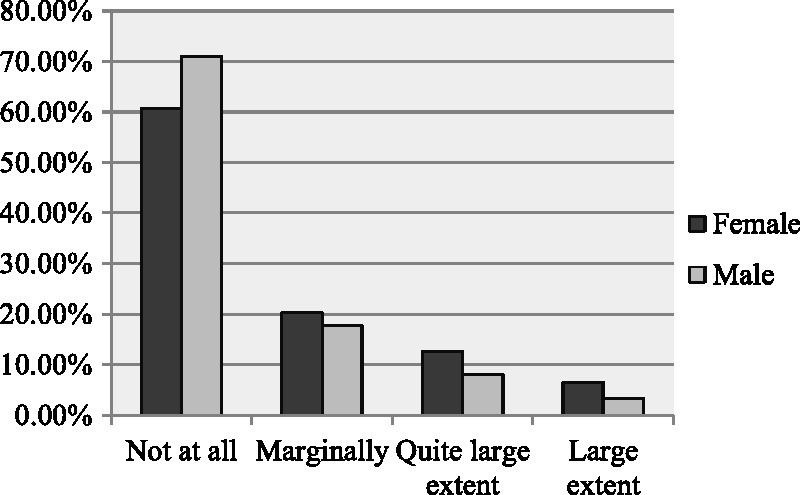

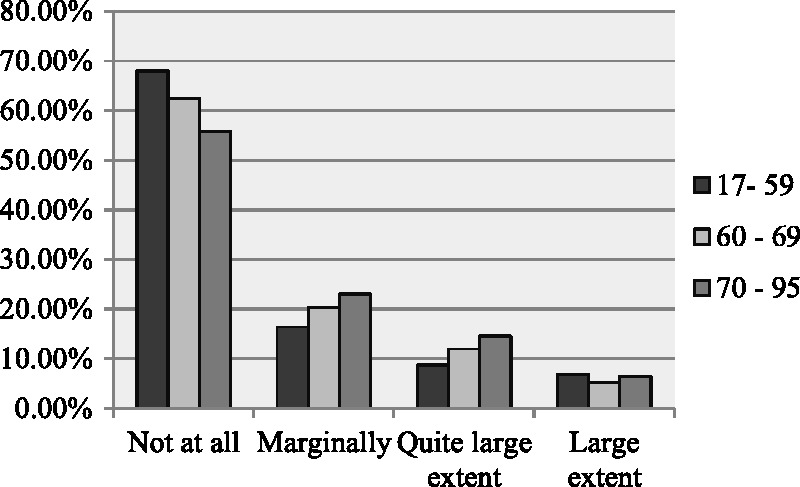

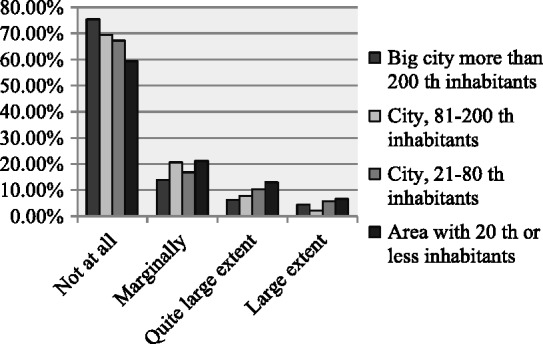

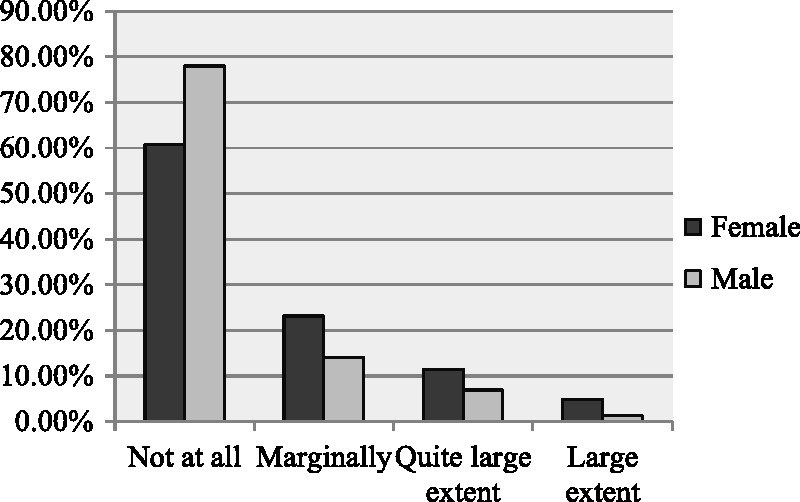

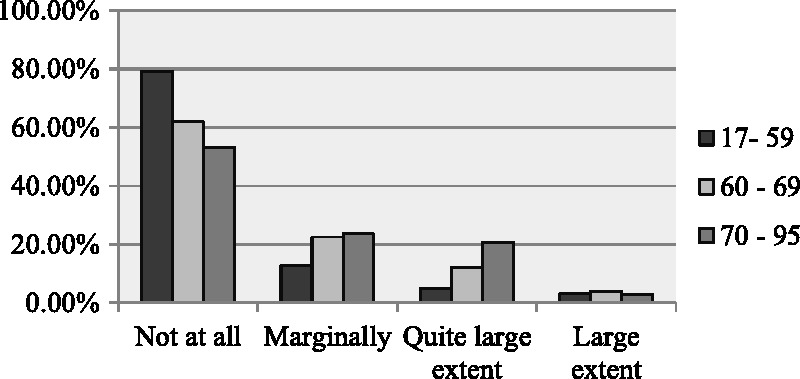

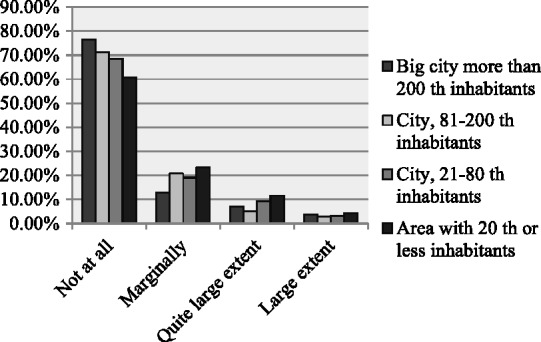

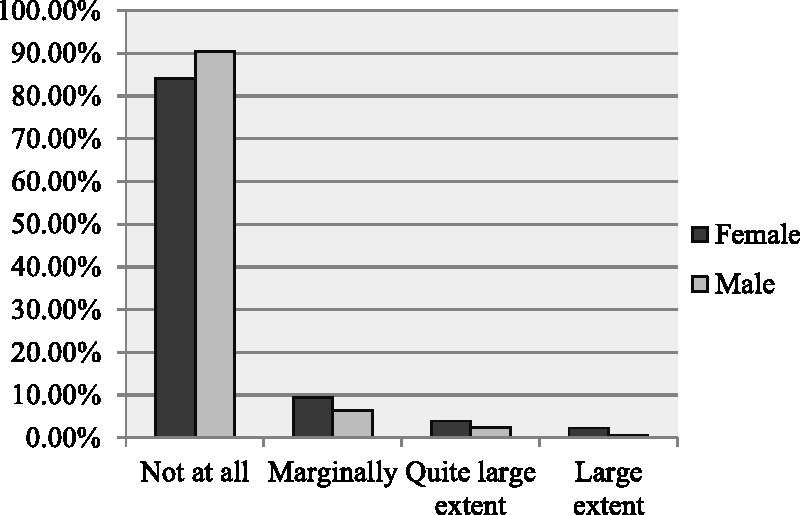

As Figures 1 to 4 show, people in the oldest age-group (70 years or older), women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average use of prayer than did younger people, men, and those who grew up in larger towns.

Figure 1.

Gender and pray to God.

Figure 2.

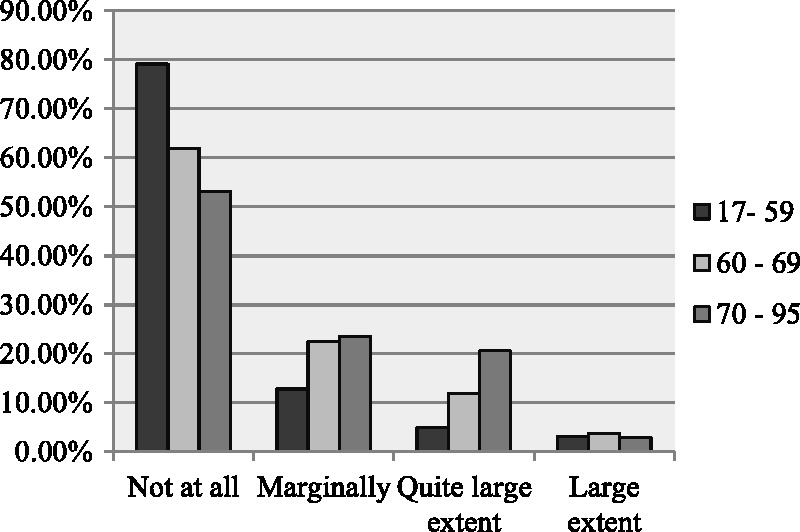

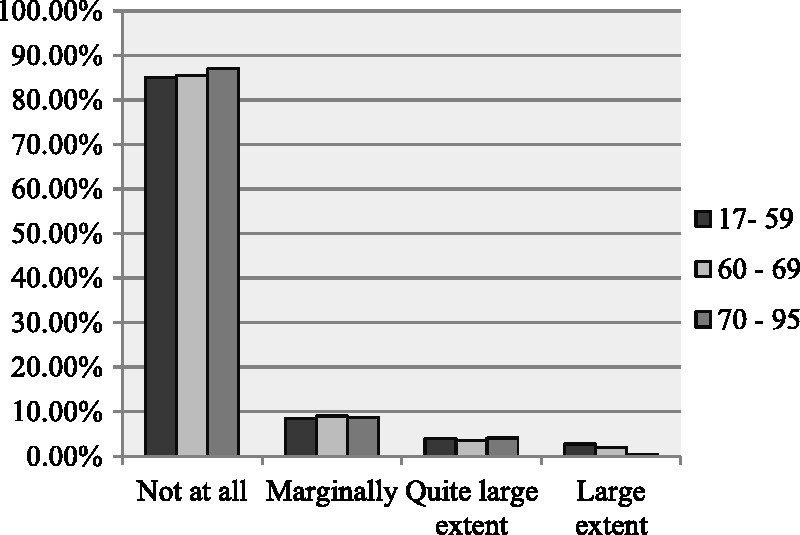

Age and pray to God.

Figure 3.

Area of upbringing and pray to God.

Figure 4.

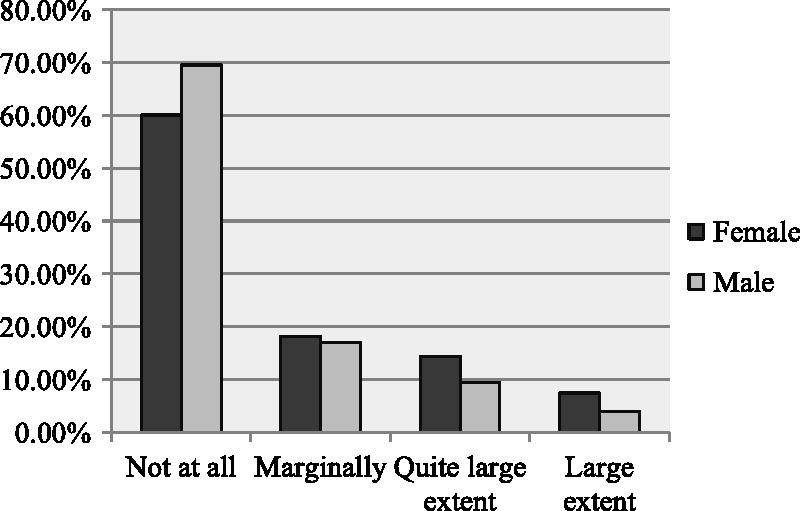

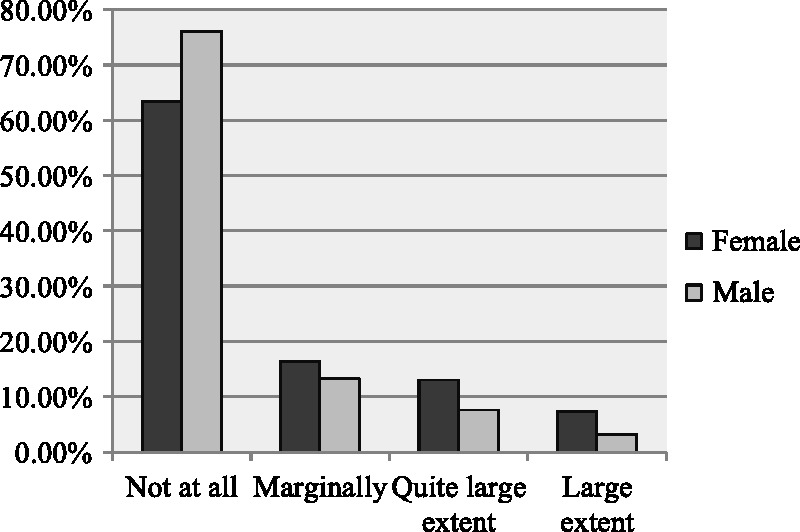

Gender and God has control.

Nearly 79% of respondents chose the alternative to a small extent or not at all when asked whether they prayed to God to make things better. Praying is clearly not a common coping method among cancer patients in Sweden, despite the fact that most respondents in the study were among the older age-group, had most likely received some religious socialization during childhood, and thus had likely had a religious upbringing. Even at school, they would have experienced some degree of Christian indoctrination, and given that secularism had not yet fully taken hold when their primary socialization occurred, they may also have had religious influences from other sources. In contrast, the results for the entire population could be expected to show less praying to God.

The present results confirm previous qualitative findings (Ahmadi, 2006, p. 108) showing that the informants were not comfortable admitting that they had asked God to make things better. Admitting weakness and needing someone to assist you, even if this someone is God, goes against the predominant pattern of socialization in Sweden, which promotes independence and self-reliance. Presumably, asking God for help was not part of people’s religious behavior under normal circumstances.

The previous qualitative study indicated that some informants sought control by praying to God. However, none of the informants reported that they had prayed for a miracle.

Thinking that you have done your best and now it’s only God who is in control

In 16th place (M = 1.6), we find the factor “Thinking that you have done your best and now it’s only God who is in control” (Table 2). One fifth of respondents (20%) reported that this factor had helped them feel better a lot or to quite a large extent when they felt stressed, sad, or depressed during or after their illness. Just more than one in 20 (7%) reported that the factor had helped them to a large extent, and one in six (18%) reported that it had helped them only marginally. Slightly more than three in five (62%) chose the option not at all.

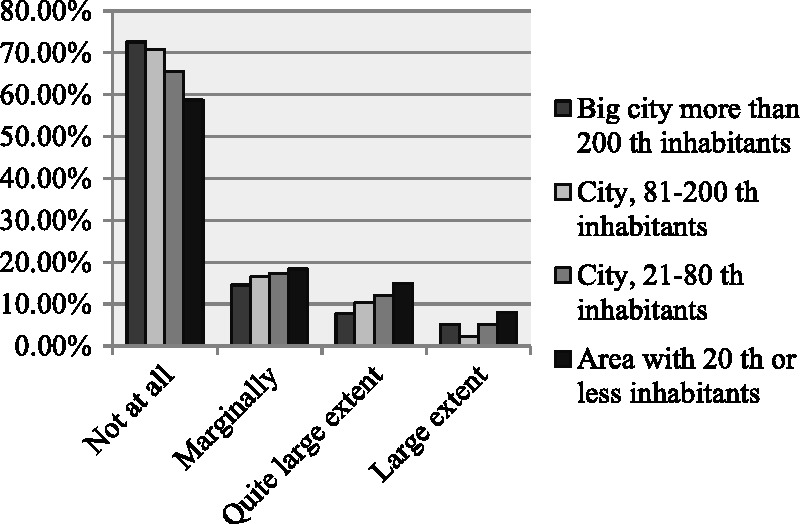

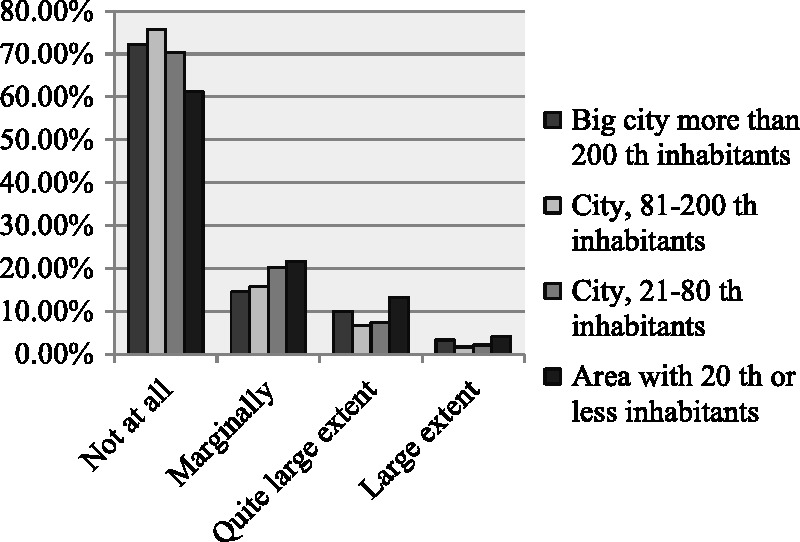

As Figures 4 to 6 show, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average on this factor than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Figure 5.

Age and God has control.

Figure 6.

Area of upbringing and God has control.

As the study showed, 80% of respondents did not ask God for help, a finding that is in complete accord with results on the method Self-Directing Religious Coping. Using this method, the individual seeks control directly through his or her own initiative rather than through God’s help. Our study shows that this coping method is prevalent among cancer patients in Sweden, an issue that will be discussed later on. The previous qualitative study as well showed a strong tendency toward using Self-Directing Religious Coping and a weak tendency toward relying on the method of pleading to God.

Thinking about God or the life of Jesus or other religious people’s lives

The factor “Thinking about God or the life of Jesus or other religious people’s lives” was in 17th place (M = 1.6; Table 2). One sixth (18%) reported that this factor had helped them feel better quite a lot or to a very large extent during or after their illness. One in 20 (6%) responded to a large extent, and one in five (20%) reported that it had helped only marginally. Slightly more than three in five (63%) chose the option not at all.

As Figures 7 to 9 show, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average on this factor than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Figure 7.

Gender and Thinking about God or Jesus.

Figure 8.

Age and Thinking about God or Jesus.

Figure 9.

Area of upbringing and Thinking about God or Jesus.

Thinking that you have ever had a sense of a strong connection with God

In 18th place (M = 1.6), we find the factor “Thinking that you have ever had a sense of a strong connection with God” (Table 2). One sixth of respondents (18%) reported that this factor had helped them feel better a lot or to quite a large extent when they felt stressed, sad, or depressed during or after their illness. One in 20 (6%) reported that the method had helped to a large extent, while one in six (16%) responded to a small extent. Two in three (66%) chose the option not at all.

As can be seen in Figures 10 to 12, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average on this method than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Figure 10.

Gender and strong connection with God.

Figure 11.

Age and strong connection with God.

Figure 12.

Area of upbringing and strong connection with God.

Going to church

The factor “Going to church” was in 19th place (M = 1.5; Table 2). One seventh (14%) reported that this factor had helped them to a large or very large extent. A few respondents (4%) indicated very large extent. One in five (21%) replied to a small extent. Nearly two in three (64%) chose the option not at all.

As we see in Figures 13 to 15, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns. In the earlier qualitative study, none of the interviewees reported use of church attendance as a coping method (Ahmadi, 2006, p. 114).

Figure 13.

Gender and going to church.

Figure 14.

Age and going to church.

Figure 15.

Area of upbringing and going to church.

Listening to religious music

The factor “Listening to religious music” was in 20th place (M = 1.5; Table 2). One seventh (14%) reported that this factor had helped a lot or to a very large extent when they felt stressed, sad, or depressed during or after their illness. A few (3%) responded to a large extent. One in five (20%) replied to a small extent. Almost two in three (65%) chose the option not at all.

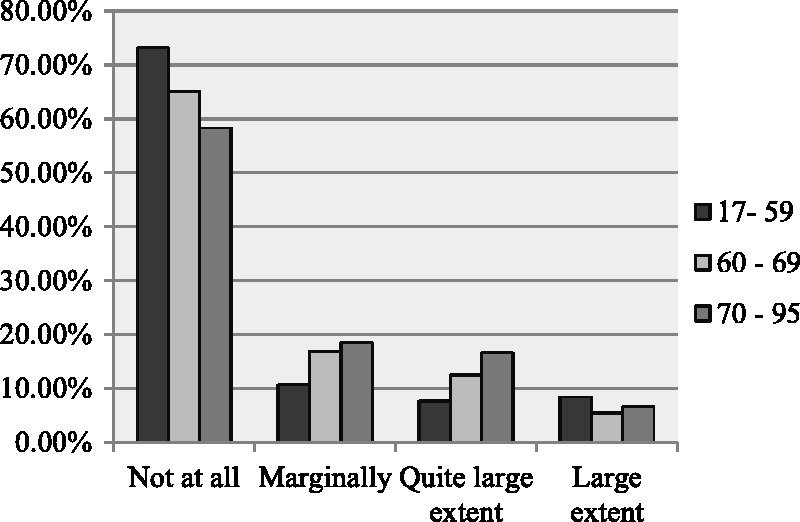

As shown in Figures 16 to 18, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

Figure 16.

Gender and listening to religious music.

Figure 17.

Age and listening to religious music.

Figure 18.

Area of upbringing and listening to religious music.

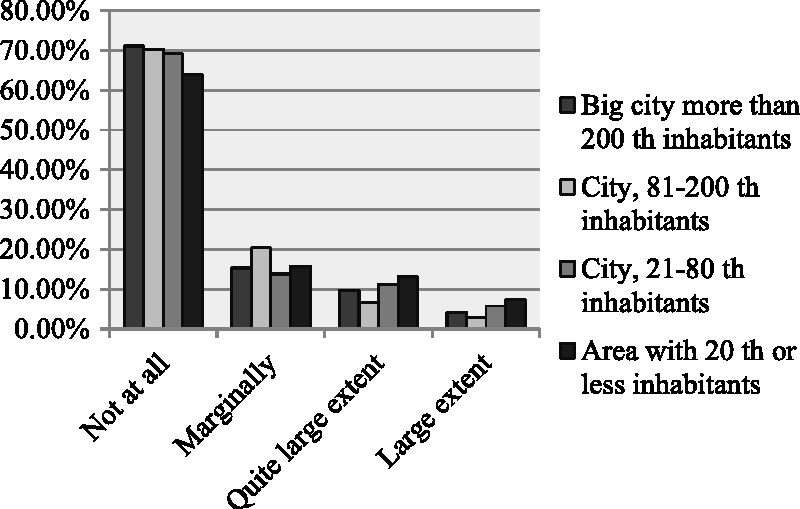

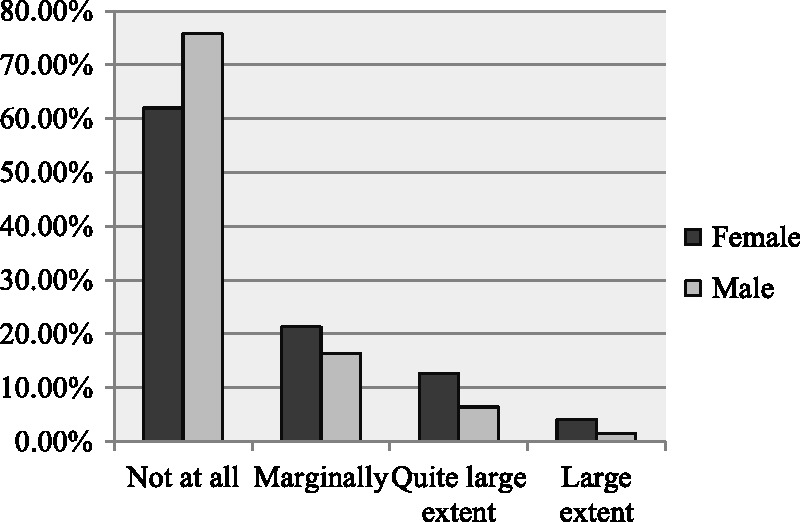

Seeking spiritual help from a priest or other religious leader

In last place (M = 1.2), we find the factor “Seeking spiritual help from a priest or other religious leader” (Table 2). One in 20 (6%) replied that this factor had helped them feel better a lot or to quite a large extent. A few (2%) responded to a large extent. One in 10 (9%) reported that this method had helped to a small extent. Six in seven (86%) chose the option not at all.

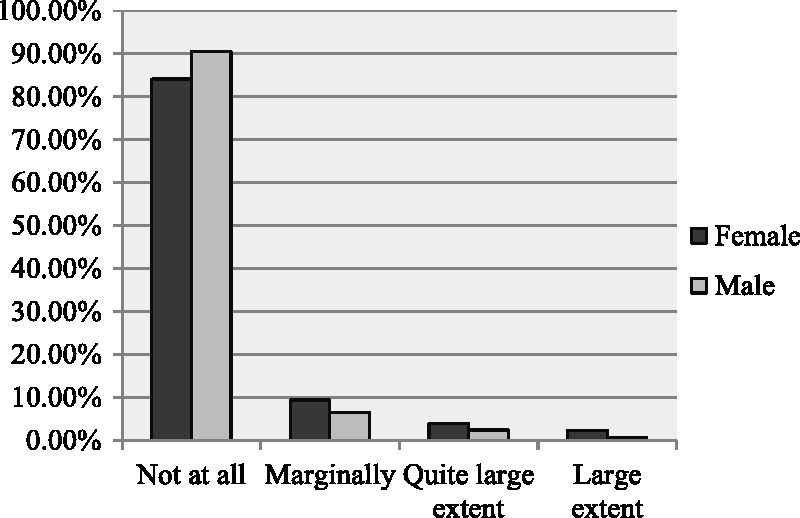

As we see in Figure 19, the women’s average was higher than the men’s. With regard to other variables, such as age and area of upbringing (Figures 20 and 21), the differences were not significant.

Figure 19.

Gender and seeking help from a priest or other religious leader.

Figure 20.

Age and seeking help from a priest or other religious leader.

Figure 21.

Area of upbringing and seeking help from a priest or other religious leader.

The Negative Religious Coping Methods

The previously mentioned eight religious coping methods, which respondents were asked to rate based on the degree to which these methods had helped them feel better during or after their illness, have been considered positive in nature. But in addition to these coping methods, three additional methods, which have been considered negative strategies, were included in the questionnaire. Negative religious coping has been described as an expression of “a less secure relationship with God, a tenuous and ominous view of the world, and a religious struggle in the search for significance” (Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998, p. 712).

The following question was posed to examine the first negative religious coping method: Have you wondered whether God has abandoned you or have you been angry that God was not present to assist you?

As Table 2 shows, only 3% of respondents reported believing that God had abandoned them or feeling anger toward God and that this had helped them feel better to quite a large extent when they felt stressed, sad, or depressed during or after their illness. A few (1%) responded to a large extent; one in 10 (9%) reported that it had helped only marginally. Nearly nine in 10 (88%) chose the option not at all. People in the youngest age-group (59 years or younger), women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher mean value for this question than did older people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

The question regarding the second negative religious coping method was as follows: Have you ever felt that God has given you your health problems because of your actions or because you have not been sufficiently faithful?

As we see in Table 2, only 2% of respondents chose to quite a large extent. A small number (less than 1%) responded to a large extent. Almost one in 10 (8%) replied marginally. Nine out of 10 (90%) answered not at all. No significant difference was found between different groups of respondents when answering this question.

The question regarding the third negative religious coping method was as follows: Have you ever felt that your illness was caused by an evil power?

As Table 2 shows, only 1% of respondents chose to a large extent or to quite a large extent in response to this question. A small number (less than 1%) replied to a large extent. One in 20 (5%) selected to a small extent. Nineteen of 20 (94%) responded not at all. No significant difference was found between different groups of respondents concerning this question.

As the study shows, very few respondents (1% to 3%) have used any of the three negative coping methods, a result that is in accord with findings from the previous qualitative study. Drawing concrete conclusions about these results is difficult, but we wish to put forward the following hypothesis:

Applying negative coping methods such as these presumably requires a belief in God or Satan, a power that can determine the course of people’s lives: a God who not only created human beings but also constantly controls each individual’s deeds and destinies, or in the same vein, a Devil who has the power to change our lives. However, among Protestant Swedes, the predominant view of God is of a Creator God who has left us to determine their own destinies and make our own history. This view is one possible explanation, among many, for why these negative coping methods were rare among the respondents.

Discussion

The purpose of the present survey study was to determine to what extent results obtained in the qualitative study can be applied to a wider population of cancer patients in Sweden. The present study shows that use of religious coping methods is infrequent among cancer patients in Sweden. Concerning the influence of background variables, the study indicates that gender, age, and area of upbringing played an important role in almost all of the religious coping methods that are used by respondents. In general, people in the oldest age-group, women, and people raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents showed a higher average use of religious coping methods than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns.

As explained previously, the respondents were asked to rate the degree to which 24 different items had helped them feel better when they, during or after their disease, felt stressed, sad, or depressed.

For each factor, respondents could choose among four response alternatives: not at all, to a small extent, a lot or to quite a large extent, and to a very large extent. The scale was transformed to a numerical scale where 1 is not at all and 4 is to a very large extent, and a mean value was calculated for each factor.

In the following, the religious coping strategies are ranked according to their mean value and their position in the ranking of the 24 items. The number in front of each method indicates its position in the ranking (Table 2)

12 Listening to religious music

13 Praying to God to make things better

16 Thinking that you have done your best and now only God is in control

17 Thinking about God or about the life of Jesus or other religious people’s lives

18 Thinking that you have ever had a sense of a strong connection with God

19 Going to church

24 Seeking spiritual help from a priest or other religious leader

This ranking shows clearly that use of religious coping methods is not prevalent among cancer patients in Sweden. Besides the two methods that are ranked in 12th and 13th place, that is, in the middle (Listening to religious music and Praying to God to make things better), the other methods received the lowest rankings.

These results illustrate the nonsignificance of religious methods as methods of coping with cancer in Sweden.

A brief study of Swedish history shows us that belief in a personal God has decreased in Sweden during recent decades, whereas belief in a transcendent power has increased (Ahmadi, 2006; Hagevi, 2012; Hamberg, 1998, 2001; Lövendahl, 2008; Pettersson & Riis, 1994). Although until 2001 a large majority in Sweden belonged to the Lutheran Church, only a minority were committed to the Church (Halman & Pettersson, 2002; Pettersson, 2008; Riis, 1992).

Halman (1994) noted that the Scandinavian countries are generally viewed as a “separate part of Europe, internally homogeneous and very different from the rest of Europe” (p. 59). One of the most important reasons why the Scandinavian countries have a special position within Europe is the influence of Protestantism (Peabody, 1985).

Christianity did not become the official religion in Sweden until the 11th century, and the institution of the Church underwent great changes after the Uppsala Meeting in 1593. The monolithic church of the time was replaced with a monolithic state that had one of the most complete legislative systems of any country and sought to create spiritual conformity within a civilized population. The destiny of Christianity in Sweden was affected significantly by this change. An important example was the ordinance of konventikelplakatet (Church Laws of 1726). The growing pietistic movement in the early 18th century led to the state church passing a law against private religious meetings, or konventikel. According to this law, the only allowable religious meetings were those led by a parish priest or by the head of a family, who could lead prayers with his family (a practice called husandakt). Holding any other kind of religious meeting could be punished by a fine or even prison. This ordinance is probably one of the reasons behind the high level of privatization of religion and of secularization of social and private life that Swedes exercise today.

The repeal of the konventikelplakat in 1858 enabled several new religious movements to prosper. However, the contemporary society—and especially the church—did not accept all of these groups, which led to many people emigrating as groups; an example was the Jansonites, who moved to the Chicago area in the United States. Furthermore, criticism of the church and Christianity by the labor movement in the early 20th century is probably one the key factors behind the low degree of church attendance and religious activities among Swedes (see Kallenberg, Bråkenhielm, & Larsson, 1996). Although a large majority of Swedes belong to the national Lutheran Church, only a minority of people in Scandinavian society and among church members are actually committed to the church (Halman, 1994, pp. 63–64).

Many Swedes who are not committed to the church consider themselves members of the Lutheran Church, probably because of the strong association in Swedens between the Lutheran Church and the state.6 According to Halman (1994), “Being a church member is almost a citizen’s duty in the Scandinavian countries” (p. 64). This link with the church can be viewed as an expression of solidarity with Swedish society and its basic values, rather than as commitment to the church as a religious institution (Hamberg, 1994, p. 184). Halman (1994) noted that “membership is widespread and is part of Scandinavian identity, but this membership is not accompanied by strong commitment to the church” (p. 79). Consequently, being a member of the church in Sweden is probably less religiously meaningful than in other countries.

The role of the church in Sweden is quite limited. According to the European Value Study 1990,7 people

reject the idea that the church should speak out on personal issues like homosexuality, abortion, extramarital affairs, and euthanasia. However, Scandinavians are also less in favour of churches speaking out on various social issues, like unemployment, disarmament, third world problems, racial discrimination, ecology and so on … .This may be explained by the fact that more than in other countries the Lutheran church in Scandinavia is an institution merely limited to providing religious services. The church is one among many other specialized institutions with a very limited role in society. As a consequence it is very difficult for the church in Scandinavia to get involved in issues which are ascribed to other institutions … It is therefore not unexpected that Scandinavians are least of all of the opinion that churches provide adequate answers to moral questions, problems of family life, spiritual needs and social problems. (Halman, 1994, p. 65)

The difficulty in finding informants for the present study who attended church, prayed, or read the Bible for religious comfort in a time of crisis was therefore not unexpected and was in accord with findings from previous studies (Jänterä-Jareberg, 2010; Pettersson, 2008), including the qualitative study discussed here (Ahmadi, 2006). For instance, according to a nationwide study among Swedes, only 16% of respondents prayed weekly, and only 9% attended church at least once a month (Hamberg, 1998, p. 181). Statistics from the Church of Sweden reveal that only 2% of members regularly attend worship services (Jänterä-Jareberg, 2010, p. 2).

Another point that explains the decreasing of belief in a personal God during the recent decades in Sweden is urbanization. It is not a revelation that those who live in rural areas show greater religiosity than those in urban areas. In addition to the more recent urbanization, one must also consider that village-like thinking had been given a blow and rationality promoted already during earlier centuries.

Although urbanization happened in Sweden later than in many other European countries, it permeated the social structure of the entire Swedish society. One of the important reasons for this was the land reform of the 18th and 19th centuries. As Lewin (2008) mentions, “In the 18th century and 19th century major government imitated land reforms were carried through, often against the will of local farmers, with the aim of facilitating rational farming” (p. 130). The reforms, Lewin (2008) explains,

put the fields together and made sure that each farm consisted of adjacent fields! As a result, the village structure disappeared … villages were broken up and neighbors suddenly were kilometers away. The close collaboration needed to farm in the village-structured countryside was replaced by breaded reliance on rationally planned farming in increasingly independent units. (p. 130)

As the villages disappeared, in the classical meaning, the village way of thinking also changed in Sweden. The change of view of religion, as explained earlier, is partly due to this change.

Conclusions

As stated, the present study showed that Self-Directed Religious Coping was the most prevalent religious coping method among cancer patients in Sweden. As Wong-McDonald and Grouch (2000) maintained, “People who are less committed tend to be more self-directive or referring, whereas those who are more committed may choose to work collaboratively with God” (p. 150). The previous qualitative study (Ahmadi, 2006) showed that fear and powerlessness are factors that cause people to work collaboratively with God in coping, thus not to work on their own. The qualitative study also found a number of informants who, although less committed or noncommitted Christians, sought more active collaboration with God or a higher power in solving their problems owing to their feelings of powerlessness or fear (Ahmadi, 2006, p. 110).

The question of who turns to God and who relies on herself or himself in a crisis is too complicated to be addressed solely by looking at the extent of individual religious commitments. In addition to background and situational factors, the culture within which a person was socialized is still an important factor. As suggested by Ahmadi (2006), culture influences the ways in which people cope with crises and, consequently, it affects whether they turn to religion and whether individual believers decide to seek God’s help or face the crisis alone.

Regarding the impact of the background variables, the present results show that gender, age, and area of upbringing played important roles in almost all of the religious coping methods used by our informants.

On the whole, people in the oldest age-group, women, and those raised in places with 20,000 or fewer residents had a higher average of use of religious coping methods than did younger people, men, and those raised in larger towns. Concerning the religious coping method seeking spiritual help from a priest, only women had a higher average than the other groups did.

Author Biographies

Nader Ahmadi, PhD, is an associate professor of sociology. He is currently dean of the Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies at the University of Gävle, Sweden. His research has mainly focused on areas such as welfare and social policy, international social work, identity and youth problems, coping strategies among cancer patients, and sociocultural perceptions of the self and gender roles. He has an extensive track record of international research and development projects in more than 15 countries, from Eastern Europe to Central and Southeast Asia. He has been working as consultant for UNICEF, UN, World Bank, and European Union.

Fereshteh Ahmadi, PhD, is a professor of sociology. She is now working as a professor at the Faculty of Health and Occupational Studies, University of Gävle, Sweden, presently specializing in issues related to health and religion and spirituality. Besides, she has conducted research on gerontology, international migration, Islamic Feminism, and Music and Coping at the Uppsala University. She is responsible for an international project on meaning-making coping. The project contains besides Sweden, South Korea, China, Japan, and Turkey.

Appendix

World Values Survey Wave 6: 2010–2014. Important in life: Religion

| Very important | 7.9 |

| Rather important | 18.3 |

| Not very important | 38.5 |

| Not at all important | 34.3 |

| No answer | 0.7 |

| Don't know | 0.4 |

| (N) | (1,206) |

Notes

As Zuckerman (2007) explains, Norris and Inglehart (2004) found that 54% of Swedes do not believe in God. According to Bondeson (2003), 74% of Swedes said they did not believe in a personal God. According to Greeley (2003), 46% of Swedes do not believe in God, though only 17% self-identify as atheists. According to Froese (2001), 69% of Swedes are either atheists or agnostics. According to Gustafsson and Pettersson (2000), 82% of Swedes do not believe in a personal God. Davie (1999) found that 85% of Swedes do not believe in God.

RCOPE is a relatively new theoretically based measure that assesses the full range of religious coping methods, including potentially helpful and harmful religious expressions (Pargament et al., 2000, p. 521). This measure is based not only on the global indicators of religiousness (e.g., frequency of prayer, congregational attendance) but also on how individuals make use of religion to understand and deal with stressors. Moreover, RCOPE reflects the nonstatic nature of coping (Ahmadi, 2006, p. 41).

The word faith, as used in religion, refers to the ability to believe something despite evidence. The ultimate level of faith is believing in something even though it is obvious to everyone that it cannot be true.

Available from www.skop.se

The present results on religiousness are not in accord with findings from the World Value Study (WVS), which includes the entire population of Sweden (see WVS statistics on the importance of religion). According to the European Barometer Study, only 23% of the Swedish population reported believing in God (European Commission, 2005, p. 225; Jänterä-Jareberg, 2010, p. 2). Other sources have indicated that as much as 85% of the Swedish population self-identified as nonreligious (Jänterä-Jareberg, 2010, p. 2). As the WVS showed, only 7.9% reported that religion was very important to them, while 18.5% reported that it was rather important, 38.5% reported that it was not very important, and 34.3% reported that religion was not at all important to them (see Appendix).

In Sweden, the national Lutheran Church, State Church, was until 2000 bounded to the State.

The European Values Study is a large-scale, cross-national, and longitudinal survey research program on basic human values, initiated by the European Value Systems Study Group in the late 1970s, at that time an informal grouping of academics. Now, it is carried on in the setting of a foundation, using the (abbreviated) name of the group European Values Study.

Author Contributions

Nader Ahmadi and Fereshteh Ahmadi have designed, conducted, analyzed, and wrote the text together. Both authors read and approved the final article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ahmadi F. (2006) Culture, religion and spirituality in coping: The example of cancer patients in Sweden, Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. [Google Scholar]

- Alma H. (1998) Identiteit door verbondenheid: Eden godsdienstpsychologisch onderzoek naar identificatie en christelijk geloof [Identity through alliance: A study in the psychology of religion on identification and Christian faith], Kampen, Netherlands: Kok. [Google Scholar]

- Bondeson U. (2003) Nordic moral climates, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Buber M. (1970) I and thou, New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Davie G. (1999) Europe: The exception that proves the rule? In: Berger P. (ed.) The desecularization of the world, Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. (1915) The elementary forms of religious life, New York, NY: Free Pres. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (January–February 2005) Special Eurobarometer 225/Wave 63.1, Brussels, Belgium: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1961) The future of an illusion, New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Froese P. (2001) Hungary for religion: A supply-side interpretation of the Hungarian religious revival. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40(2): 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. (1950) Psychoanalysis and religion, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gall T. L., Migues de Renartat R. M., Boonstra B. (2000) Religious resources in long term adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 18: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. (1966) Religion as a cultural system. In: Banton M. (ed.) Anthropological approaches to the study of religion, London, England: Tavistock, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Greeley A. (2003) Religion in Europe at the end of the second millennium, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson G., Pettersson T. (2000) Folkkyrkor och religiös pluraism—den nordiska religiösa modellen [People churches and religious pluralism-the Nordic religious model], Stockholm, Sweden: Verbum Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hagevi M. (2012) Beyond church and state: Private religiosity and post-materialist political opinion among individuals in Sweden. Journal of Church and State 54(4): 499–525. doi:10.1093/jcs/csr121. [Google Scholar]

- Halman L. (1994) Scandinavian values: How special are they? In: Pettersson T., Riis O. (eds) Scandinavian values. Religion and morality in the Nordic countries, Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Uppsaliensis, pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Halman L, Pettersson T. (2002) Moral pluralism in contemporary Europe: Evidence from the Project Religious and Moral Pluralism (RAMP). Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 13: 173–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg E. (1994) Secularization and value change in Sweden. In: Pettersson T., Riis O. (eds) Scandinavian values: Religion and morality in the Nordic countries, Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Uppsaliensis, pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg E. M. (1998) Kristen på mitt eget sätt: En analys av materialet från projektet livsåskådning i Sverige [Christian in my own way: An analysis of the data obtained from the project View of Life in Sweden], Stockholm, Sweden: Religionssociologiska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg E. M. (2001) Kristen tro och praxis i dagens Sverige [Christian faith and practice in today’s Sweden]. In: Bråkenhielm C. R. (ed.) Världbild och mening: En emperisk stidie av livsåskådningar i dagens Sverige [Worldview and sense: An empirical study of philosophies in today’s Sweden], Nora, Sweden: Nya Doxa; Retrieved from http://www.crs.uu.se/digitalAssets/55/55502_Religion_in_the_Secular_State.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hvidt N. C. (2007) Tro og helbred. Teologiske perspektiver på religiøs coping [Faith and health. Theological perspectives on religious coping]. Tidsskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund 6: 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hvidt N. C. (2008) Patienters tro på mirakler – En positiv eller negativ ressource? [Patient belief in miracles – A positive or negative resource?]. Omsorg: Nordisk Tidsskrift for Palliativ Medcin 25: 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hvidtjørn D., Hjelmborg J., Skytthe A., Christensen K., Hvidt N. C. (2014) Religiousness and religious coping in a secular society: The gender perspective. Journal of Religion & Health 53(5): 1329–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänterä-Jareberg M. (2010) Religion and the secular state in Sweden: National report on Sweden. Research programme: The IMPACT of religion: Challenges for society, law and democracy, Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R. A., Pargament K. I. (1995) Religion and spirituality as sources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Ontology 13(1–2): 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. E. (1959) Psychology of religion, Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press; Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kallenberg K., Bråkenhielm C. R., Larsson G. (1996) Tro och värderingar i 90-talets Sverige [Beliefs and values in the 1990s in Sweden], Örebro, Sweden: Libris. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H. G., King D. E., Carson V. B. (2012) Handbook of religion and health, New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaCour P., Hvidit N. C. (2010) Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: Secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Social Science Medicine 71(7): 1292–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin B. (2008) Sexuality in the Swedish context. In: Traene B., Lewin B. (eds) Sexology in context: A scientific anthology, Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lövendahl L. (2008) Privatreligiositet. In: Svenberg I., Westerlund D. (eds) Religion i Sverige, Stockholm, Sweden: Dialogos Förlag, pp. 2932. [Google Scholar]

- Norris P., Inglehart R. (2004) Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padela A. I., Curlin F. A. (2012) Religion and disparities: Considering the influences of Islam on the health of American Muslims. Journal of Religion and Health 52(4): 1333–1345. doi:10.1007/s10943-012-9620-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I. (1997) The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice, New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I., Koenig H. G., Perez L. M. (2000) The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial variation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I., Smith B., Koenig H. G., Perez L. M. (1998) Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37(4): 710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Peabody D. (1985) National characteristics, New York, NY: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson T. (2008) Sekularisering [Secularization]. In: Svenberg I., Westerlund D. (eds) Religion i Sverige [Religion in Sweden], Stockholm, Sweden: Dialogos Förlag, pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson, T., & Riis, O. (Eds.). (1994). Scandinavian values. Religion and morality in the Nordic countries. Uppsala, Sweden: Acta Universitatis Uppsaliensis.

- Phelps A. C., Maciejewski P. K., Nilsson M., Balboni T. A., Wright A. A., Paulk E., Prigerson H. G. (2009) Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. The Journal of the American Medical Association 11: 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R., Higgo R. (2010) Psychiatry, religion and spirituality: A way forward. The Psychiatrist 34: 452–453. [Google Scholar]

- Powell L. H., Shahabi L., Thoresen C. E. (2003) Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist 58(1): 36–52. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riis, O. (1992). Secularization in Scandinavia. Paper presented at the Nordic Conference for the Sociology of Religion, Skálholt, Iceland.

- Shih W. J. (2002) Problems in dealing with missing data and informative censoring in clinical trials. Current Controlled Trials in Cardiovascular Medicine 2: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan R. P. (2006) Blind faith: The unholy alliance of religion and medicine, New York, NY: St Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan R. P., Bagiella E., Powell T. (2001) Without a prayer: Methodological problems, ethical challenges, and misrepresentations in the study of religion, spirituality, and medicine. In: Plante T. G., Sherman A. C. (eds) Faith and health: Psychological perspectives, New York, NY: Guilford Press, pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan R. P., Bagiella E., VandeCreek L., Hover M., Casalone C., Hirsch T. J., Poulos P. (2000) Should physicians prescribe religious activities? The New England Journal of Medicine 342(25): 1913–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N., Vanderwerker L. C., Paulk E., Pearce M. J., Kasl S. V., Prigerson H. G. (2006) Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9(3): 646–657. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.9.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torbjørnsen T., Stifoss-Hanssen H., Abrahamsen A. F., Hannisdal E. (2000) Kreft og religiositet: En etterundersøkelse av pasienter med Hodgkin’s syndom [Cancer and religiosity: A follow-up study of patients with Hodgkin’s syndrome]. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 3: 346–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-McDonald A., Grouch R. L. (2000) Surrender to God: An additional coping style? Journal of Psychology and Theology 28(2): 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer B. J., Pargament K. I. (2005) Religiousness and spirituality. In: Paloutzian R. F., Parks C. L. (eds) Handbook of psychology and religion, New York, NY: The Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer B. J., Pargamnet K. I., Scott A. B. (1999) The emerging meaning of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality 67(6): 889–919. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman P. (2007) Atheism: Contemporary rates and pattern. In: Martin M. (ed.) The Cambridge companion to atheism, Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]