Abstract

Increasing numbers of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are entering postsecondary education; however, many report feeling lonely and isolated. These difficulties with socialization have been found to impact students’ academic success, involvement within the university, and overall well being. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess, within the context of a multiple-baseline across participants design, whether a structured social planning intervention would increase social integration for college students with ASD. The intervention consisted of weekly meetings to plan social activities around the student with ASD's interests, improve organizational skills, and target specific social skills. Additionally, each participant had a peer mentor for support during the social activities. The results showed that following intervention all participants increased their number of community-based social events, extracurricular activities, and peer interactions. Furthermore, participants improved in their academic performance and satisfaction with their college experience. Results are discussed in regards to developing specialized programs to assist college students with ASD.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, transition to adulthood, socialization, higher education

Many individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have difficulties with communication and socialization throughout the lifespan (Graetz, 2010; Zager & Alpern, 2010). These difficulties can create significant barriers to successful outcomes in the transition phase to adulthood (Howlin, Goode, Hutton & Rutter, 2004). Specifically, social deficits in young adults with ASD can impact participation and success in higher education, which has been linked to quality of life, future employment, self-confidence, and personal skill building (Van Bergeijk, Klin & Volkmar, 2008; Zafft, Hart, & Zimbrich, 2004). Although the anticipated wave of individuals with autism who have higher education goals has created some discussion in the field, there is still a paucity of research and services for this population (Cimera & Cowan, 2009; Nevill & White, 2011; Van Bergeijk et. al., 2008; Zager & Alpern, 2010).

For both students without disabilities and students with autism, college should be an environment that promotes academic and personal skill building, future employment, increased self-confidence and integration into a community (Webb, Patterson, Syverud, & Seabrooks-Blackmore, 2008; Zafft et al., 2006). For students with disabilities, college should be a natural and inclusive environment that builds self-confidence and increases independent living skills (Hart, Grigal, & Weir, 2010). Previous research indicates that adults with ASD report that they desire social relationships and to contribute to their community, but they often experience loneliness due to a lack of involvement and social skill deficits (Adreon & Durocher, 2007; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009; Howlin, 2000; Muller, Schuler, Yates, 2008). For students with ASD, leisure activities are frequently isolated activities such as playing video games and watching television (Hendricks & Wehman, 2009). Additionally, adults on the spectrum indicate that initiating social interactions is a significant challenge (Muller et al., 2008, p. 179).

Unfortunately, current services do not typically address the range of supports needed to assist college students on the spectrum with their unique and often complex needs (Hendricks & Wehman, 2009). Many of the comprehensive services received in elementary, middle, and high school through the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process are no longer available during the college years (Graetz & Spampinato, 2008; National Council on Disability, 2000). Further, there is minimal research on the development, implementation, and evaluation of programs, and little is known about the effectiveness of support programs to serve the college student population with ASD (Grigal et al., 2001; Stodden et al., 2001). Thus many students with ASD that enter postsecondary education have limited success due to a lack of available services (Webb et al., 2008).

To be specific, general services provided by Disabled Students Programs generally do not include support for increasing socialization (Adreon & Durocher, 2007; Hart et al., 2010). For example, college students on the spectrum are often challenged by finding existing social activities, lack the confidence to independently go to social events, and/or have challenges with organizational skills, all which interfere with their ability to successfully participate in social activities. As a whole, adjusting to the social pressures of postsecondary education and independent living are among the most challenging areas for college students with disabilities, particularly given the fact that the literature suggests that experiencing success at the undergraduate and graduate level requires an individual to demonstrate advanced social skills (Nevill & White, 2011; Webb et al., 2008). Thus, students with ASD typically struggle with the transition to college, not because they lack the cognitive abilities to be successful, but because they experience challenges with new social interactions in an unfamiliar place (Wenzel & Rowley, 2010). In short, adults with disabilities are increasingly attending college, but their social participation and integration in the university is still below the level of students without disabilities (Dillon, 2007). Consequently, the literature suggests concentrated efforts to include students on the spectrum among their peers without disabilities and to increase community participation of students with ASD on college campuses (Grigal et al., 2001; Hart et al., 2010; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009). These efforts may help students with ASD productively engage in activities to promote integration into social networks and relationship development (Grigal et al., 2001; Hendricks & Wehman, 2009).

Preliminary research suggests that structured social planning is an effective method for increasing social activities for college students with ASD (Koegel, Ashbaugh, Koegel, Detar & Regester, 2013). Structured social planning consists of: (a) Incorporating motivational interests to determine social activities; (b) Engagement in chosen social activities; (c) Training in organizational skills; and (d) Use of a peer mentor for support (Koegel et al., 2013). Preliminary research shows that this intervention is successful in increasing the number of social activities with typical peers for college students with ASD (Koegel et al., 2013).

This study aimed to further this research by examining the effectiveness of a structured social planning intervention on measures related to social integration within the community and college environments. Specifically, we asked the following research questions: (a) Will the social planning intervention produce improvements in the participants’ involvement in campus and community-based social activities; (b) Will the intervention produce an increase in the number of extracurricular activities for participants; (c) Will the intervention lead to interactions with more peers; (d) Will the intervention be associated with collateral improvements in academic performance; and (e) Will the intervention result in collateral gains in participants’ reported satisfaction with socialization and their college experience?

Methods

Participants and Setting

Three college students with ASD participated in this study. Each participant met the following criteria: (a) A diagnosis of an Autism Spectrum Disorder by an outside agency according to criteria in the DSM-IV TR or DSM-5 and confirmed through our center from individuals with an expertise in autism (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; American Psychiatric Association, 2013); (b) Current student in a higher education setting; (c) Between 18-25 years of age; (d) Able to speak in full, syntactically correct sentences; (e) No history of violence or aggressive behavior; and (f) Demonstrated social difficulties measured by self-report and direct observation (i.e. confirmed through direct observation reported challenges developing friendships and feeling isolated, reported an average of less than three social activities per week, and discussed an average of less than one extracurricular activity with peers per week). Each participant also completed the Adult Autism Spectrum Quotient questionnaire to help indicate severity of autism traits (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al. 2001). Table 1 presents information on each participant.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Nina | Hannah | Aaron | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 24:0 | 21:4 | 19:2 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Male |

| Academic Status | Academic Probation | Academic Probation | Good Standing |

| Residence | Parent's home | Parent's home | Parent's home |

| Ethnicity | European | Caucasian | Caucasian |

| Diagnosis | ASD | ASD | ASD |

| Autism Quotient Score | 27 | 17 | 32 |

The three most severe students, in regard to a low level of social engagement with peers, were selected from a pool of approximately 10 college students receiving services. Participants had not received behavioral intervention for autism in the past five years, and all had an IQ in the average or above average range. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study and all were informed that they would receive structured social planning to attempt to improve their socialization.

College Students with ASD

Participant One

Nina was 24 years, 0 months at the start of the study and of European origin. Nina was a first-year transfer student at a four-year university (beginning her third year of college) and her major was Studio Art. At the start of the study, Nina was on academic probation for a low grade point average (below a 2.0). She was referred to the Autism Center by a social worker at the University Student Health Center who felt that her social difficulties were interfering with her academic performance. Nina reported that she failed all of her classes during her first quarter at the four-year university, and would like to improve her social and academic situation. She lived at home with her parents and had a part-time job at a local grocery store. In addition to a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Nina also had an outside diagnosis of Anxiety, Depression and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder from a local psychiatrist and reported taking antidepressant medication at the start of the study. During a clinical interview prior to the start of intervention, Nina discussed having no friends at the university and no extracurricular activities. She also expressed having difficulty initiating interactions with new people, and reported challenges staying connected with previous friends.

Participant Two

Hannah was 21 years, 4 months at the start of the study and of Euro-American origin. At the start of the study, Hannah was a second-year student at a four-year university and her major was Mechanical Engineering. She was on academic probation from the university at the onset of the study due to a low grade point average (below a 2.0). During the study, Hannah took a leave of absence from the four-year university and enrolled at a community college. In addition to a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder, Hannah had a diagnosis of Depression from a local psychiatrist and reported taking antidepressant medication. She lived at home with her parents and had a part-time job at a local karate studio. Hannah did not engage in extracurricular activities with peers and spent the majority of her free time in her room at home. She noted that she had concerns about building and maintaining friendships, and stated that she did not have many friends at college. In a clinical interview, Hannah stated that her primary reason for services was to improve her academics, but also reported that she would like to develop more friendships at college and get involved in more extracurricular activities.

Participant Three

Aaron was 19 years, 2 months at the start of the study and of Euro-American origin. He was a first-year student at a community college and his major was undeclared. He lived at home with his parents and was referred to the Autism Center by his mother. Aaron received a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in elementary school, but had not received any clinical intervention in the past five years. In a clinical interview, Aaron reported that he did not participate in extracurricular activities, had difficulty initiating to peers, and spent most of his time alone. He stated that he was not satisfied with his interactions with other students and would like to engage in social activities, but that he was not confident in his ability to find social events to attend.

Peer mentors

During intervention, each participant was matched with a typical peer mentor. The peer mentors were similarly-aged undergraduate research assistants that received practicum course units through the university. All peer mentors were upper division undergraduate students that had taken an undergraduate course in autism or received training in the symptoms and treatment of ASD. The clinician helped arrange for the peer mentor to attend the planned social activity with the participant and provide social support for the participant during the event. The peer mentors were instructed to model and assist the participants to appropriately engage and interact with peers at the social activity. This included reminding the participants of the activity, modeling appropriate interactions, prompting the participant to interact with others, providing support to the participant during peer interactions, and providing feedback to the clinician after the activity. While at the social activity, support was provided discreetly to respect the participants’ confidentiality. Peer mentors attended at least one clinic session each month to discuss the social activities with the clinician and participant (e.g. the participant's follow through on attending social events, appropriateness of social conversation at events, etc.) Additionally, peer mentors met with the clinician once before beginning the social activities and then attended weekly group supervision meetings. During these meetings, the peer mentor provided feedback from the social activities and the clinician provided assistance in planning for subsequent sessions. Thus, each peer mentor received individualized feedback relating to supporting their participant during the social activities.

Settings and Materials

All baseline, intervention, and follow-up sessions were conducted at the Koegel Autism Center on the University of California, Santa Barbara campus. Intervention was implemented in a clinic room or office that contained a computer and large chairs. All social activities took place with peers in each student's natural environment on a college campus (e.g. dining commons, recreation center, dormitory, student organization events, etc.), the community (e.g. restaurants, local beaches, bowling alley, movie theater, etc.) or the home (e.g. playing games, cooking).

Experimental Design and Procedures

The effectiveness of structured social planning for college students with ASD was evaluated using a multiple baseline across participants design (Barlow, Nock & Hersen, 2009; Campbell, 1988; Heppner, Kivlighan & Wampold, 1999; Zhan & Ottenbacher, 2001). Baseline sessions were systematically staggered for three, seven and eleven weeks for Nina, Hannah, and Aaron, respectively. Following baseline, structured social planning intervention was then implemented in the clinic for one hour per week for a period of 10 weeks. Follow-up data were also collected under the same conditions that were in effect for the baseline sessions for three weeks following the end of intervention with each participant.

Baseline

During the baseline phase the clinician met with the college student once weekly for an hour. No instructions were provided concerning social activities. Rather, the participants were asked to continue as they normally would in their everyday lives. In order to control for the fact that a social activity log would be employed later in the intervention condition, each student was instructed to keep a daily social activity log of all social activities attended throughout the week. Participants were instructed that a social activity must involve at least one peer and the activity must not be an academic or vocational requirement. Additionally, the clinician provided a minimum of three examples of a social activity (e.g. lunch with a peer, recreational class, student organization meeting) and three examples of non-social activities (e.g. exercising on their own, attending class, going to dinner with their family). During each weekly session, the social activity log was reviewed for the previous week (i.e. the duration, setting, and peers involved were reviewed for all recorded activities).

Intervention

Intervention sessions were conducted one time per week for approximately one hour. The structured social planning intervention consisted of the following components: (a) Incorporation of the participant's motivational interests; (b) Participant's choice in social activity in which to engage from a menu of activities based on their unique interests; (d) Training in organizational skills related to the social activity; (d) Support from a typical peer mentor; and (e) Social skills training related to communication and interaction with peers. Intervention sessions were conducted for ten weeks with each participant. A description of each component of the intervention is presented below.

Incorporation of motivational interests

During the first intervention session, the clinician met with the participant to discuss the participant's motivational interests. This was an informal interview, wherein the clinician asked the participant about their interests, likes, dislikes, and other preferences. The clinician also probed for information regarding the participant's hobbies, social activities of interest, extracurricular activities in high school, career path, and goals for the future. For all three participants, the clinician also received informal information from the parents via email or phone contact regarding the participant's interests and preferred activities. Generally, the participants and their parents reported similar interests.

Menu of social activities

For each weekly intervention session, the clinician researched campus and community events, university clubs, and extracurricular activities based on the participant's interests gathered in the assessment of motivational activities. Additionally, the clinician provided training to the participant on how to find possible social activities to attend (e.g. look at the list of student clubs, read the leisure review catalog, check the campus event calendar, etc.) Each session, the clinician created a menu of at least three social activities that aligned with the interests of the participant. The options consisted of activities such as school affiliated clubs, one time social events on campus or in town, activities in the community, recreational classes, events in the dormitories, and dining or studying with peers. The participant was prompted to select a minimum of one activity that he or she would attend during the upcoming week.

Organizational skills

Each weekly session, the clinician also assisted the participant in how to manage their time to plan for the social activity that they selected. During intervention, participants were instructed to bring a daily planner or phone calendar to the weekly intervention sessions and the clinician assisted them in documenting the time, place, and activities for the week.

Peer Mentors

As previously mentioned, each participant had a peer mentor that would attend and provide support at the planned social activities. The peer mentor assisted the participant in following through in attending the social activity (e.g. provided phone reminders of the activity), modeled appropriate social behavior at the event (e.g. introduced themselves to other people at the event), and provided feedback to the participant following the social activity.

Social skills training

During weekly intervention sessions, each participant also received training in social skills related to their upcoming social event. Areas discussed included how to meet people by appropriately introducing oneself, how to appropriately exchange contact information with peers (e.g. phone numbers), how to invite peers to attend events, appropriate topics of conversation, how to ask questions to peers, appropriate ways to say “goodbye” when an activity finishes, and so on. Techniques used in social skills training often included clinician modeling and practice with feedback. In addition, the social activity from the previous week was discussed and feedback from the peer mentor was provided by the clinician.

Follow-Up

To assess for maintenance of any gains made during intervention, follow-up data were collected after the completion of intervention. Weekly data were collected for three weeks on all dependent measures to examine if any increases made in the intervention phase maintained after structured social planning was terminated.

Fidelity of Implementation

The clinician in this study was an advanced doctoral student that attended weekly supervision with a doctoral level psychologist or speech-language pathologist. To ensure consistent implementation of the structured social planning intervention, an observer scored 20% of the sessions and assessed for correct implementation of the following intervention components: (a) Incorporation of the participant's motivational interests; (b) Participant choice of activities to attend from a menu of at least three social activities; (c) Instructing the participant to organize the details of the event in their calendar; (d) Coordination of the peer mentor to attend the social event with the participant; and (e) Providing social skills training for the upcoming event. A score of eighty percent or above was considered to be effective implementation of the intervention procedures. The clinician in this study met fidelity of implementation on all scored sessions.

Dependent Measures

This study aimed to assess the impact of a structured social planning intervention on increasing social integration for college students with ASD. Therefore, data were collected on the following dependent measures: (a) Number of college and other community-based social activities attended per week; (b) Number of extracurricular activities attended per week; and (c) Cumulative number of different peers with whom the participant interacted with at social activities. In addition, collateral changes were assessed in the following areas: (d) Supplemental measure of academic performance as measured through Grade Point Average; and (e) Social validation data through a self-report questionnaire relating to the participants’ general satisfaction in their socialization and college experience. Each data category is defined below:

Community-based social activities

Due to participant reports of feeling disconnected, isolated and wishing to be a part of their campus and community, data were collected on the number of college and other community-based social activities attended each week. First, a social activity was defined as an activity with at least one other typical peer and takes place outside of the academic or vocational requirements for the student. For this study, a peer is defined as another individual that is of similar age (i.e. 18-25) to the participant. A community-based social activity was defined as a social activity that took place in the community or on a college campus (i.e. not in the home). Examples of community-based social activities include student club meetings, social activities at the recreation center, dorm activities, local dining with a peer, going to game stores with a peer, etc. See Table 2 for further examples.

Table 2.

Examples of Social Activities

| Non-Social Activities | Community-Based Social Activities with Peers | Extracurricular Activities with Peers |

|---|---|---|

| • Dinner with family • Bike ride on own • Attending class • Playing computer games on-line • Going to work • Meeting with a Professor |

• Student organization meeting • Dorm event • Dining out • Local community event (e.g. fair) • Movie theater • Outdoor activities |

• Recreational class • Student clubs • Community groups • Sports • Music groups • Volunteer organizations |

The number of community-based social activities attended by the participant each week was collected through the social log from the participant. Each participant kept record of a daily social log through the baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases. Through the social log, each participant was instructed to record (a) Each social activity they attended throughout the week and (b) Any peers they interacted with at the social activity. Each weekly session, the clinician and participant reviewed the participant's social log together, and data were obtained on the activity, duration, location, and peers involved for every social activity attended throughout the previous week. In regards to validity of the participant's social log, the peer mentor confirmed all social activities he or she attended with the participant during intervention. Additionally, the clinician randomly selected one peer social activity attended without the peer mentor each week and asked the participant to provide details of the event to show that they in fact attended the activity recorded on their social log (e.g. what time did you see the movie, who won the game, etc.) The total number of community-based social activities attended per week was calculated by summing the number of social activities recorded on campus or in the community for each participant.

Extracurricular and informal social activities

Participants reported no involvement in extracurricular activities but a desire to participant in more structured events with peers, therefore data were collected on the number of extracurricular activities attended per week for each participant. An extracurricular activity was defined as an organized activity around a specific subject that involves at least one other peer and takes place outside of the academic or vocational requirements for the student. Extracurricular activities must have a focus, and may include academic clubs, art groups, cultural organizations, volunteer groups, music groups, performance art, religious organizations, roleplaying groups, special interest clubs, sports and recreation, etc. Additionally, data were also collected on the number of informal social activities attended per week for each participant. An informal social activity was defined as a less structured activity without a specific focus that involved at least one other typical peer. Examples of informal social activities include watching a movie with a friend, having a friend over to hang out at home, etc.

Peer interactions

It was also of interest to assess whether the students with ASD continued to interact with the few peers with whom they had contact during baseline, or if their number of social contacts improved during intervention and follow up. As well, we were interested in assessing whether the participants actually interacted with peers (rather than just attending the events) during intervention and follow up. To assess the effects of structured social planning on breadth of peer interactions, data were collected on the cumulative number of different peers with whom the participant interacted at social activities during baseline, intervention and follow-up. The cumulative number of different peers with whom each participant interacted during social activities was collected through the participant's social log. For each social activity on the social log, the participant was instructed to record the names of the peers with whom they interacted at the event (i.e. exchanged at least a short conversation). The cumulative number of different peers with whom the participant interacted at social activities during baseline, intervention and follow-up were recorded for all participants.

Academic performance

Since intervention focused on increasing social activities, data were collected to assess that academics would not be adversely affected. Therefore, collateral data were collected on each participant's academic performance pre and post intervention. Academic performance was evaluated through the participant's Grade Point Average (GPA). Data were recorded on the participant's GPA for the term prior to implementation of structured social planning and for the term following the start of intervention.

Social validation

To help assess for social validity, a self-report satisfaction questionnaire was given to each participant at baseline and post-intervention to examine the participant's satisfaction with areas relating to socialization and college experience. Data were collected at baseline and post intervention on perceived satisfaction in the following areas: (a) Overall college experience; (b) Overall social experience (c) Number of social activities attended; (d) Availability of campus social events. Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction level on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Very Unsatisfied”) to 7 (“Very Satisfied”).

Reliability

Reliability was obtained by having two naïve observers independently view and code the dependent measures using the same operationalized definitions and coding procedures described above. Reliability was calculated for a randomly selected 31% of social logs throughout baseline, intervention, and follow-up for each participant. Reliability for the categorical measures of community-based social activities and extracurricular social activities was calculated using Cohen's weighted kappa coefficient (Cohen, 1968). Agreement for these measures was defined as both observers coding the social activity in the same category (e.g. both observers coding a social activity as an extracurricular activity). Cohen's weighted kappa coefficient for extracurricular social activities was 1.0, indicating perfect agreement. Cohen's weighted kappa coefficient for community-based social activities was 0.98, indicating very good agreement. Percentage agreement was 98% (range = 75%-100%) for cumulative number of different peers with whom the participant interacted with at social activities throughout the study and was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements, and multiplying by 100 to yield a percentage (Bailey & Burch, 2002).

Results

The results showed that all three participants increased their social integration following the start of intervention. Specifically, all participants increased the number of community-based social activities, extracurricular activities, and peer interactions. Additionally, collateral data showed improvement in academic performance for all participants and all reported satisfaction with their college experiencing following intervention. Results for each dependent measure are described below.

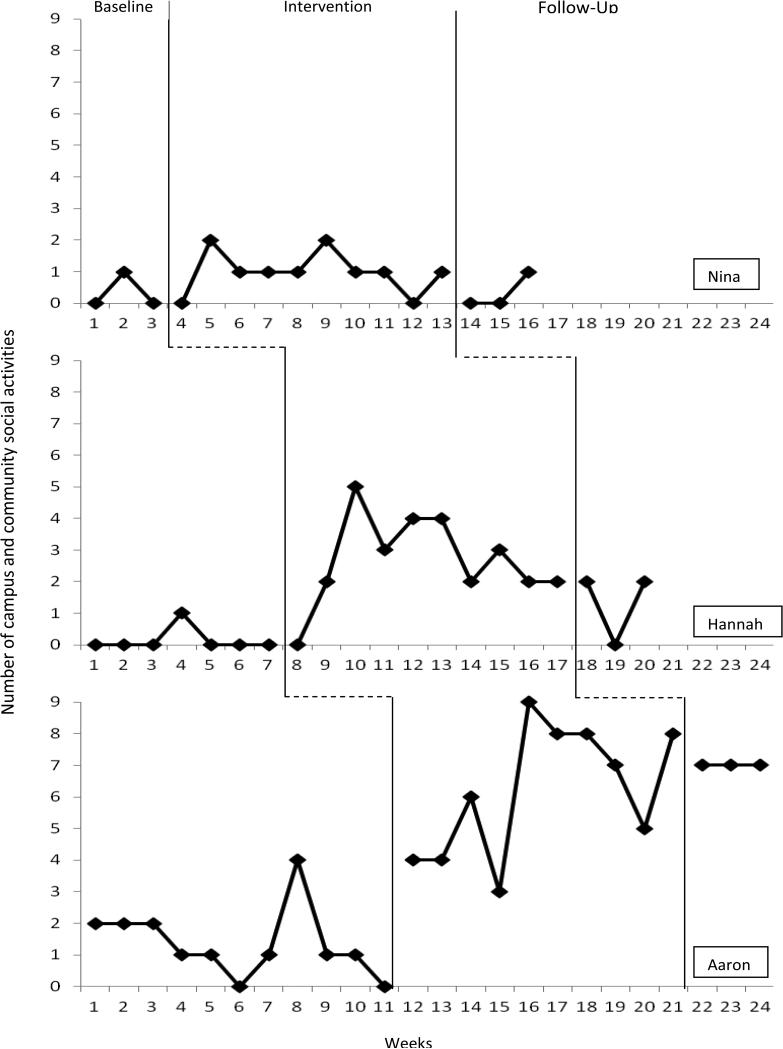

Community-Based Social Activities

Figure 1 shows the number of community-based social activities per week for each participant. During baseline, each participant attended few to no social activities on campus or in the community. Specifically, at baseline Nina engaged in an average of 0.3 social activities per week on campus or in the community (range: 0-1), Hannah participated in an average of 0.1 (range: 0-1) community-based social activities per week, and Aaron engaged in an average of 1.3 (range: 0-4) community-based social activities. Throughout the ten-week intervention, all three participants increased their number of community-based social activities each week, with Nina averaging 1 per week (range: 0-2), Hannah averaging 2 per week (range: 0-5), and Aaron averaging 6.2 per week (range: 3-9). Follow-up data indicate that both Hannah and Aaron continued to engage in an increased level of community-based social activities after intervention, with Hannah attending an average of 1.3 community-based social activities each week (range: 0-2) and Aaron averaging 7 community-based social activities each week (range: 7-7).

Figure 1.

Number of community-based social activities per week

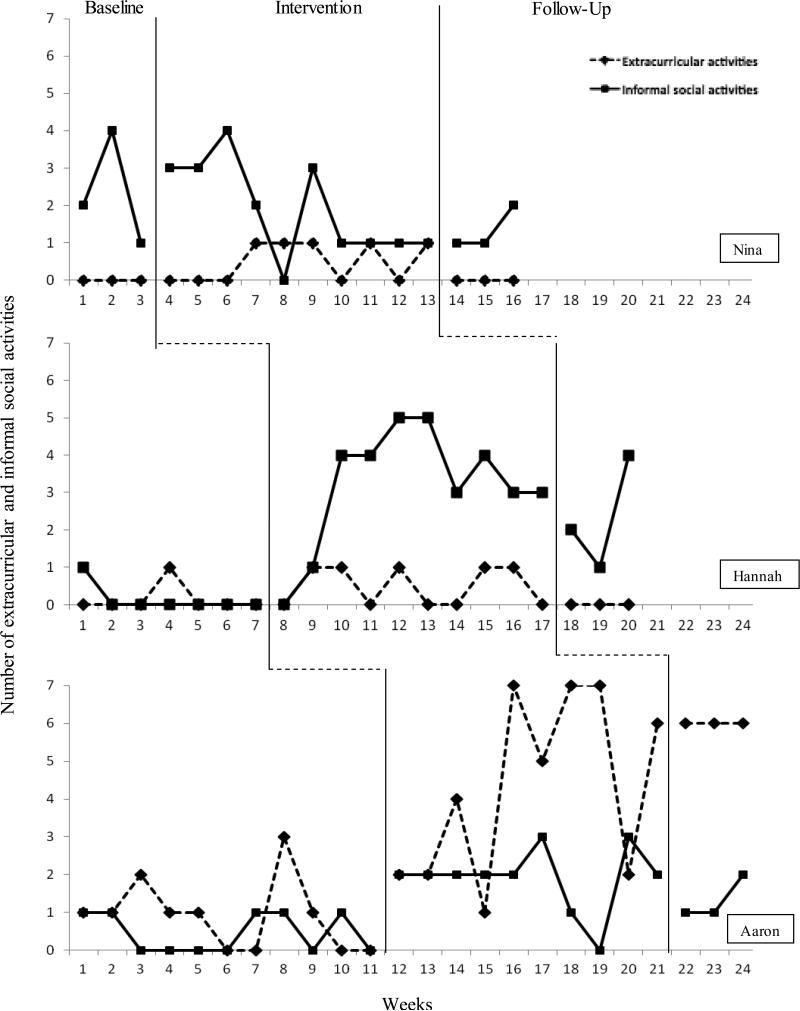

Extracurricular Social Activities

Figure 2 shows the number of extracurricular and informal social activities per week for each participant. During baseline, each participant participated in few to no extracurricular activities. Throughout the ten-week intervention, all participants showed increases in their extracurricular activities around their interests. Nina increased from zero extracurricular activities at baseline to an average of 0.5 (range: 0-1) extracurricular activities per week during intervention. Hannah increased from an average of 0.1 (range: 0-1) extracurricular activities per week during baseline to an average of 0.5 (range: 0-1) per week during intervention. Lastly, Aaron increased from an average of 0.9 (range: 0-3) extracurricular activities per week during baseline to an average of 4.3 (range: 1-7) extracurricular activities per week during intervention. Additionally, both Hannah and Aaron also increased the amount of informal social activities they attended per week following the start of intervention, with gains maintaining in follow-up. At follow-up Nina continued to engage in at least one informal social activity per week, similar to her baseline.

Figure 2.

Number of extracurricular social activities per week

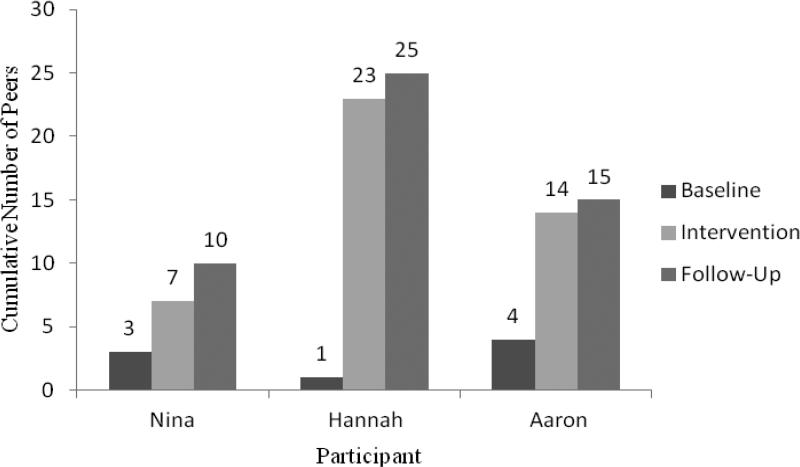

Peer Interactions

Results indicate that intervention was effective in increasing the number of different peers that participates interacted with at social activities for all three participants. Figure 3 shows the cumulative number of peers that the participated interacted with at social activities during each phase of the study. Nina interacted with three different peers at baseline and increased to interacting with seven different peers by the end of intervention and ten different peers at follow-up. Hannah interacted with only one peer throughout baseline and increased to interacting with 23 peers by the end of intervention and 25 peers at the end of follow-up. Lastly, Aaron interacted with 4 peers throughout baseline and increased to interacting with 14 peers by the end of intervention and 15 peers at the end of follow-up.

Figure 3.

Cumulative number of peers interacted with at social activities

Academic Performance

As seen in Table 3, pre and post data on participants’ Grade Point Average (GPA) indicate that each participant improved their academic performance following the start of intervention. Specifically, both Nina and Hannah were on academic probation at baseline. Nina failed all of her classes prior to intervention and received a 0.0 GPA, and Hannah withdrew from her classes before the term was complete due to not being able to earn passing grades. Following intervention, Nina received a 3.3 GPA and Hannah received a 4.0 GPA for the term. Additionally, Aaron improved his GPA from a 1.72 during baseline to a 2.20 for the term following the start of intervention.

Table 3.

Academic Performance Results

| Nina | Hannah | Aaron | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Grade Point Average | 0.0 | 3.3 | Withdrew from classes | 4.0 | 1.72 | 2.20 |

Social Validation

To assess for social validity of the treatment, data were collected on the participant's self-reported satisfaction in areas related to socialization. As seen in Table 4, all participants reported increases in satisfaction with their overall college experience, overall social experience, number of social activities they attend, and availability of campus social events. Specifically, Nina reported being somewhat unsatisfied with her college experience and unsatisfied with her socialization at baseline, and following intervention she reported feeling somewhat satisfied with her college experience and neutral with her overall social experience. Hannah reported a neutral college experience and neutral social experience at baseline, and improved to feeling somewhat satisfied with both her college experience and social experience after intervention. Furthermore, Aaron reported feeling neutral about his college experience and the number of social activities he attended at the start of the study, and following intervention he improved to being somewhat satisfied with his college experience and satisfied with the number of social activities he attended. These findings suggest that the intervention produced meaningful gains beyond behavioral data for each participant.

Table 4.

Social Satisfaction Questionnaire Results

| Satisfaction with overall college experience |

Satisfaction with overall social experience |

Satisfaction with number of social activities attended |

Satisfaction with availability of campus social events |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | Baseline | Post-Intervention | Baseline | Post-Intervention | Baseline | Post-Intervention | |

| Nina | 3 Somewhat unsatisfied | 5 Somewhat satisfied | 2 Unsatisfied | 4 Neutral | 2 Unsatisfied | 4 Neutral | 3 Somewhat unsatisfied | 4 Neutral |

| Hannah | 4 Neutral | 5 Somewhat satisfied | 4 Neutral | 5 Somewhat satisfied | 3 Somewhat unsatisfied | 4 Neutral | 3 Somewhat unsatisfied | 4 Neutral |

| Aaron | 4 Neutral | 5 Somewhat satisfied | 5 Somewhat satisfied | 6 Satisfied | 4 Neutral | 6 Satisfied | 4 Neutral | 6 Satisfied |

Discussion

These findings are encouraging for postsecondary education options for the young adult population with ASD. The results of this study extend previous research and suggest that a structured social planning intervention can be effective in increasing social integration for college students with ASD (Koegel et al., 2013). All participants engaged in an increased number of community-based social activities, increased their involvement in extracurricular activities and increased the number of different peers with whom they interacted during social activities. Additionally, intervention showed collateral gains in participant's academic performance and satisfaction with overall college experience. Two of the three participants showed large improvements, and one participant (Nina) demonstrated small improvements. Nina also had a diagnose of anxiety and had panic attacks throughout the study, which often related to social situations (although they did not increase during intervention and follow up), which may have affected her levels of improvement. These findings have several theoretical and applied implications.

First, research has found an indirect relationship between stress level for typical peers prior to enrolling in a university and their adjustment 6 months later, but students with ASD report difficulties with the transition from high school to postsecondary settings which maintain over time (Van Berjeijk et al., 2008). This may be caused by a lower level of participation in college life among students with disabilities compared to students without disabilities, and difficulties establishing relationships with peers has been found to interfere with academic achievement (Dillon, 2007). Findings from our study indicated that structured social planning was effective in improving participation in college life, and all participants improved their grade point average and were more satisfied with their college experience.

This study also suggests that it may be important to specifically target involvement in community-based social activities and extracurricular activities (Hart et al., 2010). Community-based social activities and extracurricular activities can enhance integration into an individual's natural environment, improve participation in social groups, and increase involvement in activities that may become a source of potential friends for individuals on the spectrum (Laugeson & Frankel, 2010). While it may be difficult for college students with ASD to find and attend these social activities, results from our study suggest that college students with ASD are more satisfied if they interact with peers. Hendricks and Wehman (2009) note that there is little known about the level of community integration experienced by individuals with ASD, and few research studies examine interventions that enhance community participation. This study adds to the literature that community integration appears to be important for college students with ASD, and structured social planning may be an effective intervention in this area.

In addition to conducting further research on social supports for adults with ASD, it may be helpful to disseminate information regarding structured social planning across college campuses (Dillon, 2007). This was an effective short-term intervention that may be feasible to implement across campuses, and collaboration with staff members and campus organizations may be advantageous for creating effective support programs (Dillon, 2007). While many higher education programs are increasing their awareness about ASDs, few universities are trained to provide specific services to help these students with their unique needs. Training staff members at Disabled Students Programs, Psychological Counseling Centers, Student Health Centers, and Offices of Residential Life could help students with ASD receive support to increase their socialization with peers. Additionally, research suggests that a potential moderator of academic and social success for college students on the spectrum is the attitudes and beliefs held by their typical peers (Nevill & White, 2011). It may also be important to conduct specific outreach programs to the typical student population to increase knowledge, awareness, and inclusion of students with ASD (Wenzel & Rowley, 2010).

It may also be helpful for future research to incorporate a breadth of measures and collaborate with parents and other individuals that are actively involved in the participant's life (e.g. teachers, caregivers, mentors, etc.) Assessing others’ perceptions of the participant's social and behavioral skills before and after intervention can possibly lead to a more comprehensive and complete assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention and would be helpful to include in future research. Additionally, it would also be interesting to conduct a long-term follow up to assess whether improvements in social activities may further develop after the individuals with ASD have more time and opportunities to practice socializing with peers. Adults with ASD tend to have a long history of experiencing social challenges and it seems possible that structured social planning may improve symptoms of learned helplessness that could be related to a lack of engagement in social activities with peers.

There are several limitations in the current study and potential areas for future research. For example, while three participants meets the standard criteria for multiple baseline designs, it would be helpful to replicate procedures with a larger sample size to help strengthen the external validity of the study and to assess whether the findings are applicable to a wider range of students with ASD (Kratochwill et al, 2010). Additionally, it may be beneficial to examine the effectiveness of the intervention with individuals of varying severity of symptomology of autism spectrum disorder. While each participant had an official diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder from an outside agency that was confirmed through our center, clinical observation suggests that participants may be in the “mild” range. Lastly, the racial/ethnic diversity of the current sample was limited, and is would be important to investigate cultural differences in a sample of more demographically diverse students.

In summary, this study was a step in furthering the area of developing and examining treatment techniques for college students with ASD. The findings of this study suggest that a relatively short term structured social planning intervention was effective in increasing social integration for students with ASD in higher education, and participants also improved in collateral areas beyond socialization that were not specifically targeted in the intervention. Providing support services to help postsecondary students with ASD will likely increase their ability to successfully obtain a higher education degree and in turn may improve their long-term outcome in life.

References

- Adreon D, Durocher J. Evaluating the college transition needs of individuals with high-functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic. 2007;42(5):271–279. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Burch M. Research methods in Applied Behavior Analysis. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow D, Nock M, Hersen M. Single Case Experimental Designs: Strategies for Studying Behavior Change. Pearson Education, Inc.; Boston, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. Using a single-subject research design to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1988;42(11):732–738. doi: 10.5014/ajot.42.11.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimera RE, Cowan RJ. The costs of services and employment outcomes achieved by adults with autism in the US. Autism. 2009;13(3):285–302. doi: 10.1177/1362361309103791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. Creating supports for college students with Asperger syndrome through collaboration. College Student Journal. 2007;41(2):499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Graetz JE, Spampinato K. Asperger's syndrome and the voyage through high school: Not the final frontier. Journal of College Admission. 2008;198:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grigal M, Neubert D, Moon M. Public school programs for students with significant disabilities in post-secondary settings. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2001;36(3):244–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hart D, Grigal M, Weir C. Expanding the paradigm: Postsecondary education options for individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder and intellectual disabilities. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2010;25(3):134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks DR, Wehman P. Transition from school to adulthood for youth with autism spectrum disorders: Review and recommendations. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2009;24(2):77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner P, Kivlighan D, Wampold B. Research Design in Counseling. 2nd edition Wadsworth Publishing; California: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P. Outcome in adult life for more able individuals with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism. Special Issue: Asperger Syndrome. 2000;4(1):63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel L, Ashbaugh K, Koegel R, Detar W, Regester A. Increasing socialization in adults with Asperger's Syndrome. Psychology in the Schools. 2013;50(9) [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill T, Hitchcock J, Horner R, Levin J, Odom S, Rindskopf D, Shadish W. Single-case designs technical documentation. 2010 Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Laugeson EA, Frankel F. Social skills for teenagers with developmental and autism spectrum disorders: The PEERS treatment manual. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; New York, NY.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muller E, Schuler A, Yates G. Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism. 2008;12(2):173–190. doi: 10.1177/1362361307086664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Disability (U.S.), Federal Depository Library Program, & United States National Council on Disability: Living, learning & earning. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Nevill R, White S. College students’ openness toward Autism Spectrum Disorders: Improving peer acceptance. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2011;41(12):1619–1628. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stodden R, Whelley T, Chang C, Harding T. Current status of educational support provision to students with disabilities in postsecondary education. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2001;16(3,4):189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bergeijk E, Klin A, Volkmar F. Supporting more able students on the autism spectrum: College and beyond. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(7):1359–1370. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb K, Patterson K, Syverud S, Seabrooks-Blackmore J. Evidenced based practices that promote transition to postsecondary education: Listening to a decade of expert voices. Exceptionality. 2008;16:192–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel C, Rowley L. Teaching social skills and academic strategies to college students with Asperger's Syndrome. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 2010;42(5):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zafft C, Hart D, Zimbrich K. College career connection: A study of youth with intellectual disabilities and the impact of postsecondary education. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2004;39(1):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zager D, Alpern CS. College-based inclusion programming for transition-age students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2010;25(3):151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan S, Ottenbacher K. Single subject research designs for disability research. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2001;23(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/09638280150211202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]