Abstract

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) mostly manifesting as optic neuritis and/or myelitis, which are frequently recurrent/bilateral or longitudinally extensive, respectively. As the autoantibody to aquaporin-4 (AQP4-Ab) can mediate the pathogenesis of NMOSD, testing for the AQP4-Ab in serum of patients can play a crucial role in diagnosing NMOSD. Nevertheless, the differential diagnosis of NMOSD in clinical practice is often challenging despite the phenotypical and serological characteristics of the disease because: (1) diverse diseases with autoimmune, vascular, infectious, or neoplastic etiologies can mimic these phenotypes of NMOSD; (2) patients with NMOSD may only have limited clinical manifestations, especially in their early disease stages; (3) test results for AQP4-Ab can be affected by several factors such as assay methods, serologic status, disease stages, or types of treatment; (4) some patients with NMOSD do not have AQP4-Ab; and (5) test results for the AQP4-Ab may not be readily available for the acute management of patients. Despite some similarity in their phenotypes, these NMOSD and NMOSD-mimics are distinct from each other in their pathogenesis, prognosis, and most importantly treatment. Understanding the detailed clinical, serological, radiological, and prognostic differences of these diseases will improve the proper management as well as diagnosis of patients.

Keywords: aquaporin-4 antibody, Devic’s disease, differential diagnosis, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, multiple sclerosis, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, optic neuritis

Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS), mostly involving the optic nerve and the spinal cord.1 Though it is a rare disease, a recent epidemiologic study estimated its prevalence to be as high as 10 per 100,000 in an Afro-Caribbean population.2 NMOSD characteristically shows a high female predominance from 3:1 to 9:1,3–5 is accompanied by severe disruption of the blood–brain barrier during attacks,6 mostly has a disease-specific autoantibody to aquaporin-4 (AQP4-Ab),7 and frequently manifests as severe bilateral/recurrent optic neuritis or severe longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM).8 However, diverse diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), other inflammatory diseases,9 malignancy, infection, or vascular disease can mimic NMOSD by either involving optic nerves and/or spinal cords, manifesting bilateral optic neuritis or LETM,10 showing brain lesions resembling those of NMOSD, or even having false-positive AQP4-Ab assay results.11–13 Moreover, some of the NMOSD can manifest as atypical or milder forms14 or test negative in the AQP4-Ab assay,1,15 thereby complicating the diagnosis. In this review we will cover the history of the diagnostic criteria of NMOSD, the advantage and pitfalls of the AQP4-Ab assays, and diverse diseases that can mimic NMOSD, including the key features that can distinguish them from NMOSD.

Diagnosis of NMOSD

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) was first reported by Dr. Eugène Devic in the late 19th century as a monophasic disease characterized by both severe bilateral optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (TM).16 In addition to the classic concept of the 19th century, recent studies have revealed that NMO is often relapsing rather than monophasic,17 frequently associated with a disease-specific autoantibody against AQP4-Ab,18 and can also involve the brain as well as the optic nerve and spinal cord.19

With deeper understanding of NMO, the diagnostic criteria of NMO also evolved from the version in 1999,17 through the revised one in 2006,20 and finally to the first international consensus criteria in 2015.1 The new criteria have adopted the broader term of NMOSD8 to include patients with limited manifestations. Moreover, they have stratified NMOSD into two types: NMOSD with AQP4-IgG (NMOSD-AQP4); and NMOSD without AQP4-IgG or with unknown AQP4-IgG status. According to the new diagnostic criteria, NMOSD-AQP4 refers to patients (1) who have at least one core clinical characteristics of NMOSD in either optic nerve, spinal cord, dorsal medullar, brainstem, diencephalon, or cerebrum; (2) who were tested positive for AQP4-IgG; and (3) in whom alternative diagnoses are excluded.1

The AQP4-Ab assay: implications and caveats

The AQP4-Ab is a disease-specific autoantibody to NMOSD. If tested by proper assay methods this autoantibody is rarely found in patients having other neurological diseases nor in healthy subjects.21 Therefore, the presence of serum AQP4-Ab is a highly specific diagnostic test of NMOSD as set out in the recent international consensus criteria.1 Moreover, the presence of AQP4-Ab in patients with NMOSD can predict their long-term prognosis as well as therapeutic response.14

Currently, diverse methods such as indirect immunofluorescence (IIF), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), cell-based assay (CBA), and flow cytometry assay (FACS-assay) are available for detecting AQP4-Ab. Among these, the CBAs are strongly recommended according to the 2015 international consensus diagnostic criteria.1 CBA can be performed using either live cells expressing human M23-AQP4 (live-CBA) or a commercial kit coated with pre-fixed cells expressing human M1-AQP4 (fixed-CBA). The fixed-CBA is currently widely used as it is ready-to-use and has relatively good accuracy. The live-CBA seems to have higher accuracy than the fixed-CBA, but demands a high level of technical expertise and is time-consuming, which limits its use to some specialized centers.12,22 Therefore, if AQP4-Ab assay results, performed with the fixed-CBA results, were distinct from the clinical and/or radiological manifestations of patients, it would be reasonable to re-test their samples with the live-CBA. Some studies reported that the FACS-assay, using free-floating live cells expressing human AQP4, yielded a higher sensitivity than the fixed-CBA23 or even the live-CBA.22,24 The FACS-assay could also be advantageous in that it can yield quantitative results and a cut-off discriminator. Nevertheless, as the accuracy of the FACS-assay varied greatly according to the methodological details and experience of the examiners,12 further studies for the optimal protocol of FACS-assay are needed. The IIF was the first assay to identify NMO-IgG,7 and can be useful as a screening tool for diverse antibodies against the CNS antigens, including AQP4-Ab, at a relatively low cost.25 The ELISA may easily quantify the titer of AQP4-Ab26 but has a relatively low accuracy.12,22,24

Other than the assay methods, various clinical and serological situations can lower the accuracy of AQP4-Ab assay (Table 1).

Table 1.

Conditions that may affect the diagnostic accuracy of the AQP4-Ab assay.

| • Sera sampled immediately after or during plasmapheresis/high-dose corticosteroid often lowers the titers of AQP4-Ab.27 |

| • Sera sampled during B-cell-depleting treatment (e.g. rituximab) or during remission stage may have lower titers of AQP4-Ab and be tested false-negative.22 |

| • Sera with polyclonal B-cell activation can cause non-specific binding to cells and may give false-positive results.21 |

| • Pre-fixation of the AQP4-expressing cells and/or using an M1-AQP4 isoform can interfere with the formation of the orthogonal array of particles of AQP4, and might give false-negative results.28,29 |

| • Sera with lower titers of AQP4-Ab may be tested negative in a fixed-CBA.23 |

| • Sera with highly active AQP4-Ab can destroy AQP4-expressing cells, and thereby may mask the binding of the AQP4-Ab in assays using live cells (either live-CBA or FACS-assay).13 |

| • Recently a case report showed that natalizumab can directly interact with the AQP4-expressing cells, and thereby might cause false-positive AQP4-Ab assay results in patients being treated with natalizumab.30 |

Differential diagnosis of NMOSD

According to the 2015 international panel criteria, the presence of AQP4-Ab in the sera of patients is central in diagnosing NMOSD-AQP4. Nevertheless, clinical and radiological differential diagnoses of NMOSD-AQP4 remains important for the following reasons: (1) in clinical practice, the AQP4-Ab assay may not be performed for all the patients with inflammatory disease of the CNS, or not be readily available everywhere. Rather, clinicians need to identify patients with probable NMOSD-AQP4, in whom the AQP4-Ab assay needs to be performed; (2) the test result for AQP4-Ab could be affected by such factors as types of assay and clinical and serological situations; (3) many diseases, including inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic conditions, can involve the CNS and mimic the clinical and radiological phenotypes of NMOSD-AQP4; and lastly (4) some patients with NMOSD do not have AQP4-Ab.1

Multiple sclerosis

Both MS and NMO are inflammatory diseases of the CNS with relapsing courses, especially in their early disease stages.31,32 As these two diseases share some phenotypic features, there have been long debates on whether these two diseases are fundamentally different. However, since the discovery of the disease-specific autoantibody to NMO (AQP4-Ab), subsequent studies have confirmed that these two diseases have distinct features in their epidemiology, serology, pathology, response to treatment, and prognosis. These characteristics provide important clues in differentiating the two diseases, as summarized in Table 2. Differential diagnosis of MS from NMOSD is critically important because disease-modifying treatment for MS, such as interferon-β,33,34 fingolimod,35 natalizumab,36,37 and alemtuzumab,38 are inefficacious in or may aggravate NMOSD.39

Table 2.

Distinctive characteristics of MS from those of NMOSD.

| MS | NMOSD | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | ||||

| Prevalence, per 100,0005 people | Denmark | 154.5 nationwide | 4.4 in southern Denmark | Asgari et al.,40 Bentzen et al.41 |

| US | 177 in Olmsted county | 3.9 in Olmsted county | Mayr et al.42 | |

| Martinique, France | 10 in Martinique | Flanagan et al.2 | ||

| UK | 203.4 nationwide | 1.96 in southeast Wales | Cossburn et al.,43 Mikaeloff et al.44 | |

| Japan | 10 nationwide | 3.65 nationwide | Ochi and Fujihara,45 Miyamoto46 | |

| F:M ratio | Moderate female predominance | High female predominance (9:1–3:1). | Kim et al.,5,47 Koch-Henriksen and Sorensen48 | |

| Age of onset | Median of 29 years, uncommon in children and >50 years | Mean of 40–45 years, with wide distribution from young children to elderly | Kitley et al.,4 Kim et al.,5 Wingerchuk and Lucchinetti49 | |

| Symptoms and signs | ||||

| Optic neuritis | Visual field defect other than cecocentral scotoma (per se, complete blindness, altitudinal hemianopsia, etc.) | Uncommon | Relatively common (up to 25%) | Nakajima et al.50 |

| Severe visual loss (bilaterally ⩽0.1) in the chronic stage | Uncommon (4.2% in 11 years of disease onset) | Common (50% in 10 years of disease onset) | Merle et al.51 | |

| Myelitis | Severe myelitis causing complete paraplegia | Rare | Relatively common (30–70% at first attack) | Wingerchuk52 |

| Painful tonic spasm associated with myelitis | Rare | Relatively common (up to 25%) | Kim et al.53 | |

| Brain | Intractable hiccup and nausea (associated with area postrema lesions) | Rare | Relatively common (12–17%) | Apiwattanakul et al.,54 Misu et al.55 |

| MRI findings | ||||

| Spinal cord | Longitudinally extensive spinal lesion extending three or more vertebral segments | Adult: rare (<5%) Pediatric: relatively uncommon (14%) |

Adult: very common (up to 94%) Pediatric: very common (up to 100%) |

Wingerchuk et al.,20 Banwell et al.56 |

| Location of spinal lesions on axial image | Asymmetrical and peripheral, often posterior involvement | Central gray matter involvement | Kim et al.57 | |

| Bright spotty lesions, defined as very hyperintense spotty lesions on axial T2WI | Rare (3%) | Common (54%) | Yonezu et al.58 | |

| Brain | Multiple patchy enhancement with blurred margin in adjacent regions (cloud-like enhancement) | Uncommon (8%) | Common (90%) | Ito et al.59 |

| Pattern of callosal lesions | Small, isolated, and non-edematous | Can be large and edematous | Nakamura et al.60 | |

| Lesions perpendicular to a lateral ventricle (Dawson fingers) | Common | Rare | Matthews et al.61 | |

| Lesions adjacent to lateral ventricle and the inferior temporal lobe | Common | Rare | Matthews et al.61 | |

| Large and confluent white matter lesions, sometimes resembling pattern of PRES | Very rare | Sometimes | Kim et al.,62 Magana et al.,63 Pittock et al.64 | |

| Cortical or juxtacortical lesions | Common | Rare | Matthews et al., Calabrese et al.65 | |

| Optic nerve | Optic chiasmal involvement | Rare | Relatively common (25–75%) | Storoni et al.,66 Lim et al.,67 Khanna et al.68 |

| Pattern of CNS atrophy | ||||

| More severe atrophy of the brain | More severe atrophy of the spinal cord | Liu et al.69 | ||

| Serology | ||||

| Serum AQP4-Ab | Not present | Can be present in average of 72% of NMO by in-house cell-based assay (results vary greatly according to the types of assay methods and definition of the sample populations) | Jarius and Wildemann21 | |

| Cerebrospinal fluid study | ||||

| Pleocytosis | Mild to moderate | Can be severe (up to 1,000/mm3) | Kim et al.,6 Wingerchuk et al.17 | |

| Oligoclonal bands | Present in most patients (up to 97% with repeated test); rarely disappear in follow-up sampling | Can be present in some patients (33–43%); mostly disappear in follow-up sampling | Wingerchuk et al.,17 Bergamaschi et al.70 | |

| Polyspecific antiviral humoral immune response (e.g. against measles, rubella, varicella) | Common (88%) | Rare (5%) | Jarius et al.71 | |

| Optical coherence tomography | ||||

| Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness reduction | Mostly in temporal quadrant | Mostly in superior/inferior quadrant | Schneider et al.,72 Bennett et al. 73 | |

| Pathology | ||||

| AQP4 immunoreactivity | Relatively preserved | Lost in the early stage | Lucchinetti et al.,74 Misu et al.,75 Roemer et al.,76 Misu et al.77 | |

| GFAP immunoreactivity | Relatively preserved | Can be lost in the early stage; some lesions can show clasmatodendrosis |

||

| Perivascular deposition of the immunoglobulin and complement | Rare | Common | ||

| Prognosis | ||||

| Secondary progressive course | Common | Proposed to be uncommon (2%; data were based on the 2006 NMO criteria, data based on 2015 criteria have not been evaluated yet) | Wingerchuk et al.32 | |

| Rate of disability progression | Relatively slow (median duration of 23.1 years from onset to EDSS 6 reported in earlier study, recent studies show milder disease courses) | Can be fast (median 12 years to EDSS 6) | Kim et al.,47 Confavreux et al.,78 Cree et al.79,80 | |

| Mortality | Low (life expectancy is reduced by 7–14 years compared with the general, healthy population) | Can be high (the five-year survival can be as low as 68%, as identified in an earlier study) | Wingerchuk et al.,17 Scalfari et al.81 | |

AQP4, aquaporin-4; AQP4-Ab, autoantibody to aquaporin-4; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; PRES, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

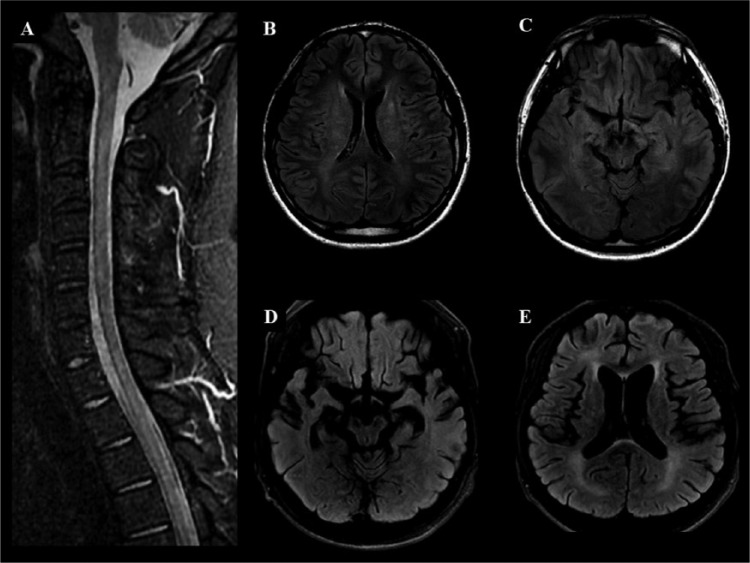

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a rare inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the CNS. It typically causes multiple simultaneous or consecutive lesions in the CNS, thereby manifesting as polyfocal neurologic symptoms including encephalopathy, motor and sensory symptoms originating from the brain, optic neuritis, and/or TM (Figure 1).82,83 Though ADEM is often monophasic, recent studies reported that relapses can occur in 10–18% of cases.44,84,85 ADEM can manifest as LETM, bilateral multiple cerebral lesions of the white matter,86 bilateral optic neuritis,87 or deep gray matter lesions,88 all of which can be seen in NMOSD.1 Moreover, a considerable number of patients diagnosed with ADEM in clinical practice did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for ADEM,84 highlighting the difficulties in defining ADEM.

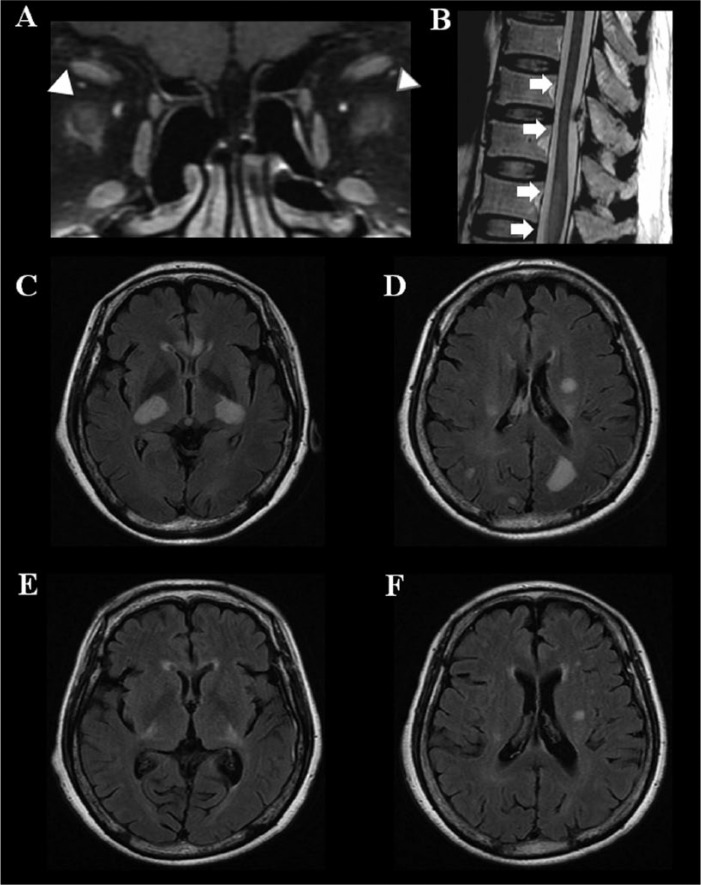

Figure 1.

Polyfocal manifestation of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. A = fat-suppressed T1-weighted image with gadolinium enhancement; B = T2-weighted image; C, D, E, and F = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR).

A 66-year-old woman developed acute bilateral blindness after 2 weeks of influenza vaccination. She developed successive paraplegia and altered mental status over the following week. On admission, the MRI revealed gadolinium enhancement in both optic nerves (arrowhead, A), acute transverse myelitis (arrow) involving lower thoracic cord and conus medullaris (arrow, B), and disseminated T2 high-intensity lesions involving the cerebral white matter and deep gray matter (C and D). She was treated with high-dose methylprednisolone followed by plasmapheresis. The brain lesions almost disappeared within 11 months (E and F). She experienced no relapse during 4 years of follow-up.

ADEM differs from NMOSD in that it has no AQP4-Ab, less or no female predominance, more polyfocal neurologic symptoms at onset, typically a monophasic disease course, and is relatively more common among pediatric patients than the latter.83,84 Moreover, the major symptom of ADEM is encephalopathy that can manifest as either alteration in consciousness or behavioral change;83 by contrast, the major symptom of NMOSD is either optic neuritis or myelitis, and only a minor proportion (about 8%) of patients with NMOSD have symptomatic cerebral syndrome at disease onset.89

Another characteristic feature of ADEM distinguishing it from NMOSD is that most patients with ADEM experience preceding infection (up to 61%) or vaccination (up to 4%) within 4 weeks before the onset of neurologic deterioration.84 A recent study on the brain lesion distribution in ADEM and NMOSD reported that brain lesions in the putamen favor the diagnosis of ADEM, whereas lesions in the hypothalamus favor the diagnosis of NMOSD.88 Though patients with ADEM have initial severe neurologic impairment and show polyfocal/diffuse MRI lesions, most of their symptoms and MRI lesions recover over the long term (Figure 1).85 Classically, uniform enhancement of all MRI lesions has been considered to be a feature that favors diagnosis of ADEM, since all lesions in ADEM can be theoretically in their same disease stage.90 Nevertheless, care should be taken in applying this features to the diagnosis of ADEM in clinical practice because enhancing MRI lesions can be found in a limited number of patients with ADEM (30–66%);82,85 moreover, some patients with ADEM may experience multiphasic disease courses83 with lesions having diverse disease stages.

Interestingly, the original concept of NMO, proposed by Dr. Eugine Devic in 1894, more closely resembled the current concept of ADEM82,83 than that of NMOSD,1 because the original concept of NMO suggested a monophasic disease course and polyfocal manifestation of optic neuritis and TM occurring at the same time or in quick succession.16 Even now, it seems that the current concept of ADEM still contains some overlaps with those of MS and NMOSD. According to the recent criteria and expert opinion for pediatric ADEM, patients with ADEM can be re-diagnosed as having either MS or NMOSD according to the number/types of relapses or test result for AQP4-Ab, respectively.83,91 These overlaps in phenotypes should be considered especially in diagnosing pediatric ADEM patients, since a relatively higher portion (up to 9%) of pediatric NMOSD-AQP4 cases can manifest as symptoms of encephalopathy mimicking ADEM.92

Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis

Acute transverse myelitis (ATM) refers to a heterogeneous group of inflammatory spinal cord disorders, resulting in motor, sensory, and/or bowel and bladder dysfunction. ATM can be a symptom of either MS, NMO, systemic connective tissue disease, infectious disease, radiation, or malignancy. However, despite extensive diagnostic workup, etiologies in some cases of ATM are unknown (idiopathic ATM, iATM). According to the definition of the Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group (TMCWG), iATM should have symptoms arising from the spinal cord, bilateral signs and/or symptoms, a clear sensory level, no extra-axial compression of the spinal cord, evidence of inflammation within the spinal cord, and progression to nadir in 4 h to ~21 days. Moreover, iATM should not have evidence of aforementioned other etiologies that cause secondary inflammation of the spinal cord.93

Although the presence of LETM is an important feature in differentiating NMOSD from MS,20 LETM can be a feature of other diseases and, conversely, short TM can occur in NMOSD-AQP4 patients.94,95 Studies in Asians and individuals of European ancestry showed that positivity of AQP4-Ab among inflammatory disease patients with LETM was as low as 18% and 53%, respectively,14,96 implying that diverse diseases, including iATM, can manifest as LETM.

A study in Europe showed that about 80% of patients with a first episode of ATM converted to MS after a mean follow-up period of 6.2 years.97 Meanwhile, the majority of ATM in the Asian cohort did not convert to MS after a mean follow-up period of 5.3 years.98 Therefore it seems that the prognosis and clinical significance of isolated ATM may depend on the ethnic background and the prevalence of MS among the population.

Notably, contrary to the definition of iATM by TMCWG, which suggested a time to nadir in 4 hours to ~21 days in iATM, myelopathy with a progressive course over months has also been reported in NMOSD,99,100 which could be attributable to successive or clustering of individual relapses of myelitis in NMOSD.17

Among patients with ATM, painful tonic spasms, defined as a paroxysmal episode of intense pain that accompanies tonic posturing of the limbs, have been reported to be more common in NMOSD than in iATM groups (25% versus 2%, respectively).53 Female gender, recurrent disease course, higher expanded disability status scale (EDSS) at the nadir of acute attack, and poor response to acute steroid treatment were also associated with the presence of AQP4-Ab among patients with isolated LETM, implying these factors can be an important clue in differentiating LETM of NMOSD from idiopathic LETM.14

Idiopathic optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is probably the most common cause of unilateral visual loss among young adults. The general features of optic neuritis includes reduction in visual acuity, field defects relative to afferent pupillary defect combined with ocular pain (92%), impaired color vision (94%), and female predominance (77%).101 Most patients begin to recover within 3 weeks from the onset of optic neuritis102 and >90% of patients have a good recovery in visual acuity of 20/40 or better in 1 year.103

As isolated optic neuritis can be idiopathic as well as a manifestation of NMOSD with distinct therapeutic responses and prognoses, differentiation of idiopathic optic neuritis from optic neuritis of NMOSD is important. Relapsing disease course, bilateral simultaneous optic nerve involvements,1 and poor visual outcome104 are often the features of NMOSD that may indicate testing for AQP4-Ab.

In patients who are suspected of having an idiopathic optic neuritis, MRI can also yield useful clues in their differential diagnoses and prognoses. As the asymptomatic lesions on brain MRI raise the risk of developing MS (78% in 15 years),105 lesions on spinal MRI might suggest underlying pathophysiology of NMOSD,1 and peri-neural enhancement patterns on orbit MRI might imply the presence of antibody against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprogein (MOG-Ab).106,107

Interestingly, even within idiopathic optic neuritis, there is a diverse range of prognoses, ranging from isolated optic neuritis, relapsing isolated optic neuritis, or chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuropathy,108 thus suggesting a heterogeneous pathogenesis of idiopathic optic neuritis.

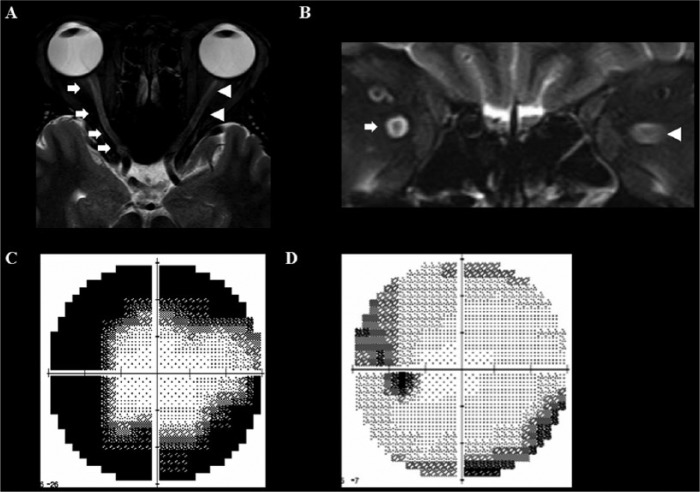

Inflammatory diseases associated with antibody to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

The myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, and is expressed on the surface of oligodendrocytes and myelin.109 Although the presence of MOG-Ab in a subgroup of patients with inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS has been an important issue, clinical implications of this antibody in earlier studies were highly controversial.110,111 Most of these controversies seem to stem from the methodological issues in the antibody assays, such as the selection of (1) linearized or denatured MOG proteins,112 (2) short-length or full-length MOG, or (3) secondary antibody against human IgG (H + L).113 At this time, the cell-based assay with the full length of human MOG-transfectant and secondary antibody against human IgG1 seem to be most useful in detecting conformation-sensitive MOG-Ab with clinical implications.113,114

The inflammatory diseases associated with MOG-Ab can manifest as a phenotype of NMOSD because they frequently have recurrent or bilateral optic neuritis106,115 and/or LETM.115,116 Nevertheless, in an adult cohort of inflammatory disease, MOG-Ab-positive patients differed from the NMOSD-AQP4 group in that the former more frequently manifested as isolated optic neuritis (83% versus 8%, respectively), had more optic nerve involvements at onset (82% versus 37%), fewer spinal cord relapses (0% versus 84%), and fewer relapsing disease courses (29% versus 90%). Interestingly, the MOG-Ab-positive patients showed a characteristic MRI feature of peri-neural enhancement on orbital MRI, which was observed in neither MS nor NMOSD with AQP4-Ab (Figure 2).106 In pediatric cohorts, MOG-Ab was frequently found in patients with ADEM (up to 43%), most of whom had two or more episode of attacks (up to 100%).117

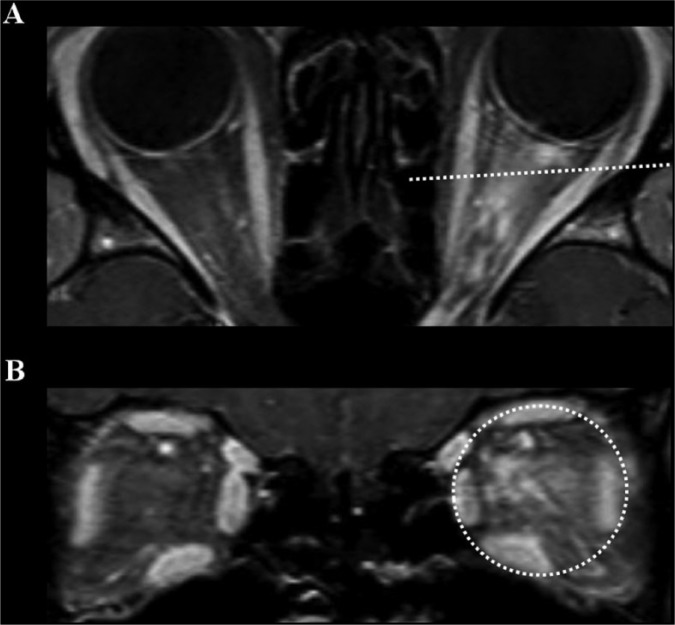

Figure 2.

Peri-neural enhancement pattern in orbit MRI of MOG-Ab-associated optic neuritis.

A 22-year-old woman presented with recurrent bilateral optic neuritis. Her orbital MRI showed extensive enhancement patterns that were not confined to the left optic nerve, but extended to the soft tissues around the optic nerve (peri-neural enhancement, A and B). She tested negative for AQP4-Ab, but positive for MOG-Ab. After treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral corticosteroids, her visual acuity recovered. This peri-neural enhancement pattern can be frequently found in optic neuritis associated with MOG-Ab.

All MRI images are T1-weighted with gadolinium enhancement; dotted lines in (A) highlight the level of the transverse images in (B).

AQP4-Ab, autoantibody against aquaporin-4; MOG-Ab, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody.

As inflammatory disease with MOG-Ab had distinctive radiological, clinical, and prognostic features from both MS and NMOSD-AQP4,106 and also as the MOG-Ab were rarely found among patients with AQP4-Ab,106,115,116 this MOG-Ab may be a specific biomarker for a disease that has a distinct pathogenic mechanism. Nevertheless, further studies, especially on the optimal assay method for detecting MOG-Ab, are needed for the exact clinical utility of this autoantibody.

Interestingly, a recent multicenter study on a cohort in Europe reported that one-third of patients with MOG-Ab can also have brainstem involvements ranging across diverse symptoms from asymptomatic cases to fatal rhombencephalitis,118 some of which might mimic brainstem involvements of NMOSD-AQP4.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease that commonly involves the lymph node, skin, lung, eye, and nervous system. The incidence of sarcoidosis is estimated to be 10.9–35.5 cases per 100,000, which was higher among female African Americans.119 Though a limited number (5–15%) of patients with sarcoidosis experience clinical involvement in the nervous system (neurosarcoidosis), both the optic nerve and the spinal cord seem to be relatively frequently involved.120 Moreover, the optic nerve (Figure 3) and spinal cord (Figure 4) involvement in neurosarcoidosis can be bilateral and longitudinally extensive, respectively,121,122 which resembles the phenotypes of NMOSD.1 As most patients with neurosarcoidosis can have systemic involvements of sarcoidosis, searching for the systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, such as bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest radiography (Figure 3), erythema nodosum, uveitis, or macular/papular skin lesions, may be first diagnostic clues.123,124 Nevertheless, in neurosarcoidosis cases without systemic involvements, histopathologic evaluation of the CNS tissue may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.121,125 In addition, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can be useful in both identifying the systemic involvement of sarcoidosis and deciding on the biopsy site.121,126 Currently, two sets of diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis are available.125,127 Among those, the most recent criteria of the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases (WASOG) suggested a category of highly probable neurosarcoidosis in the presence of a clinical picture consistent with granulomatous inflammation of the nervous system plus MRI findings of neurosarcoidosis or CSF examination suggestive of inflammation.127

Figure 3.

Right optic neuropathy and thoracic lymphadenopathies in patients with sarcoidosis.

A 55-year-old year woman presented with right optic neuropathy. Her ophthalmologic examination revealed a relative afferent pupillary defect and disc swelling in her right eye (A). Her routine chest X-ray showed hilar enlargement (arrowhead, B), and FDG-PET showed multiple lymphadenopathies in the both mediastinal, perihilar, and subclavian areas (C). Together with bronchoscopic biopsy that revealed non-caseating granuloma and the increased level of serum angiotensin converting enzyme, she was diagnosed with neurosarcoidosis. After treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by high-dose oral steroid (1 g/kg), her visual acuity improved from 0.5 to 0.8 and her lymphadenopathies were also improved (D). Interestingly, her follow-up fundus exam showed disc hemorrhage, which is uncommon in optic neuritis (E).

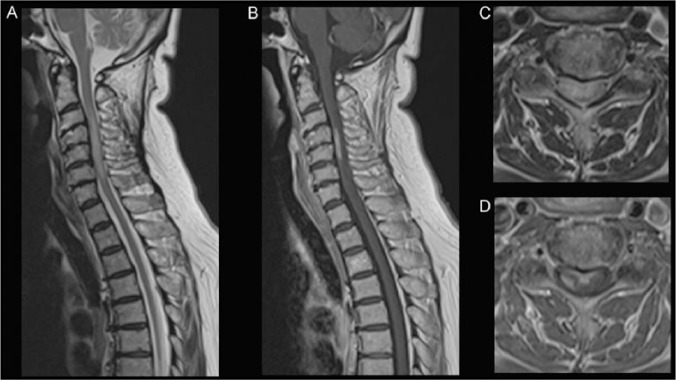

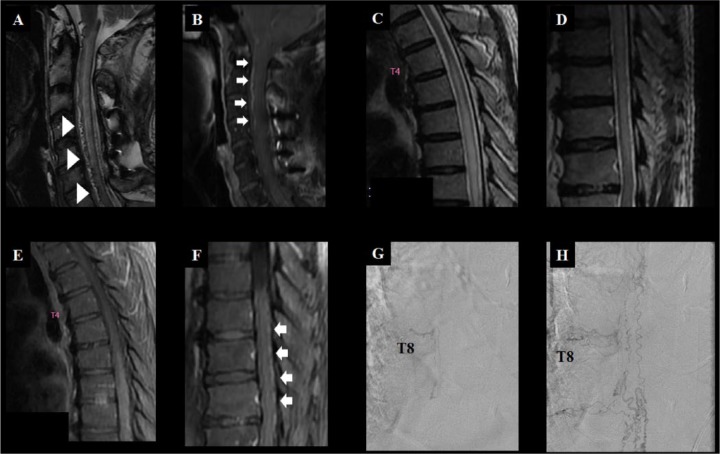

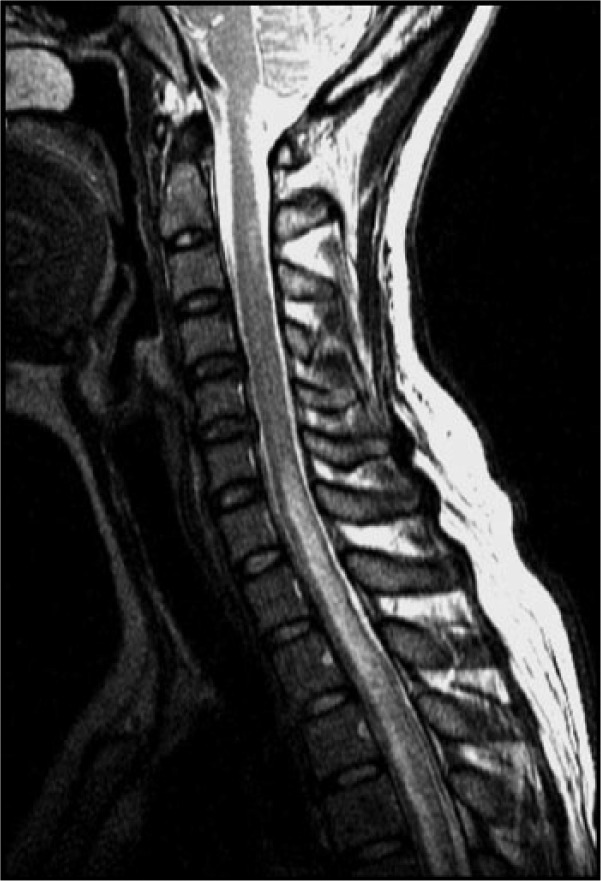

Figure 4.

Neurosarcoidosis manifesting LETM.

A 66-year-old woman with a history of ocular sarcoidosis (granulomatous uveitis) developed weakness of the right upper arm and leg, numbness and pain in her bilateral upper arm, and dysuria, which progressed for a month. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities nor lymphadenopathy. Neurological examination revealed a right hemiparesis, hyperreflexia with extensor plantar reflexes, sensory disturbance in the right C5–6 dermatome. Blood tests showed normal white blood cell count, and normal CRP and serum angiotensin converting enzyme levels. Both serum AQP4-Ab and MOG-Ab were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid examination showed a mildly elevated protein level. Chest CT revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Spinal MRI exhibited a longitudinally extensive intramedullary HSI lesion at C3–6 (A) with partial contrast-enhancement (B). Axial MRI showed transverse HSI (C); and ventral and right-sided circumferential enhancements (D). She was diagnosed with sarcoid myelopathy and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (1000 mg daily, 3 days) followed by oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg daily). Her symptoms began to improve.

A and C = T2-weighted MRI; B and D = T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium enhancement.

AQP4-Ab, autoantibody against aquaporin-4; HSI, high signal intensity; MOG-Ab, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody.

LETM in sarcoidosis can be differentiated from LETM in NMOSD in that the former has a greater prevalence of elevated angiotensin converting enzyme, dorsal cord subpial gadolinium enhancement extending over two or more vertebral segments, and persistent contrast-enhancement (>2 months),121 but these features may not always be present.

CNS involvement in patients with systemic autoimmune disease

Sjogren’s syndrome

Most myelitis cases associated with Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) have longitudinally extensive spinal cord involvement, meet the diagnostic criteria for definite NMO, or are tested positive for AQP4-Ab (Figure 5). Moreover, their clinical, radiological, and prognostic spectrum do not differ from NMO patients without SS.128 Given the fact that the AQP4-Ab is not found in SS patients without CNS involvement129 and the finding that brain involvement in SS is similar to that in NMOSD,130 most of the CNS involvement in SS seem to be the manifestations of coexisting NMOSD rather than the result of the direct CNS involvement in SS.128

Figure 5.

Coexistence of the neuromyelitis optic spectrum disorder and SS.

A 37-year-old woman with a history of bilateral optic neuritis presented with paraparesis. Her spinal MRI showed LETM and she was positive for AQP4-Ab. Meanwhile, she also had SS, according to the symptoms (dry eye and mouth), signs (positive scintigraphy and Shirmer’s test), histopathology (lymphocytic infiltration in the salivary gland biopsy), and a positive anti-Ro antibody result. She had NMOSD-AQP4 and SS.

AQP4-Ab, autoantibody against aquaporin-4; LETM, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; NMOSD-AQP4, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder with AQP4-Ab; SS, Sjogren’s syndrome.

Systemic lupus erythematous

Unlike SS, systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) can involve the CNS (CNS lupus) in a diverse way. Most patients with CNS lupus manifest as headache (54%), seizure (42%), hemiparesis (24%), or memory impairment (24%), and only a small number of patients have optic neuritis (7.3%) or myelitis (4.9%).131 Though most of these symptoms in CNS lupus are distinct from those in NMOSD,47,132 some patients with SLE have coexisting NMOSD-AQP4, or vice versa, which could be attributable to a susceptibility to multiple autoimmunity in those patients.129,133

CNS lymphoma

Primary CNS lymphoma can sometimes be misdiagnosed as NMOSD for a number of reasons. (1) The brain MRI patterns of primary CNS lymphomas are highly variable.134 Moreover, brain lesions in NMOSD can frequently be large, confluent, or tumefactive.1 (2) Both the primary CNS lymphoma (Figure 6) and NMOSD can develop longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions,135 and about 40% of patients with spinal cord lymphoma have intramedullary spinal MRI lesions without swelling of the spinal cord mimicking non-tumorous etiology. (3) Treatment with corticosteroid can, at least initially, lead to an improvement of both clinical symptoms and MRI findings in primary CNS lymphoma.136

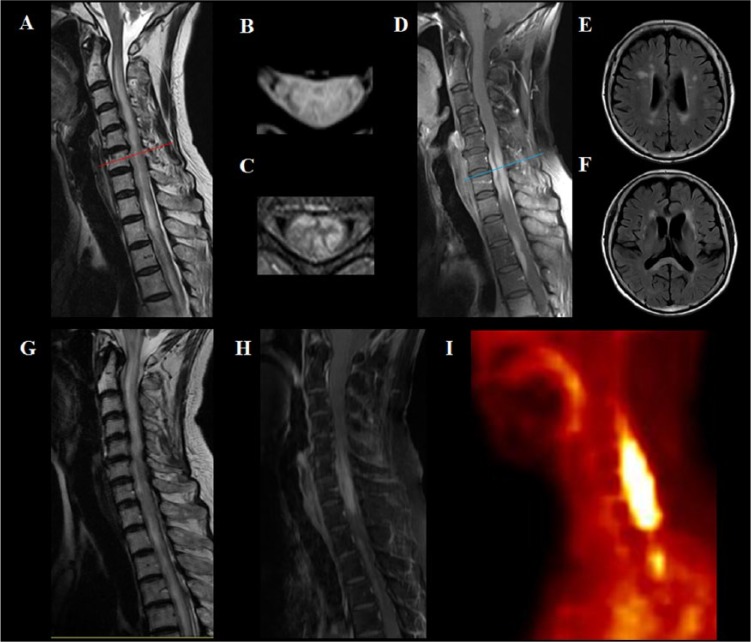

Figure 6.

Primary CNS lymphoma manifesting as a longitudinally extensive myelitis.

A 70-year-old female presented with subacute paraplegia. Her initial spinal MRI showed T2 HSI lesions that were longitudinally extensive (A) and involved almost the entire width of the spinal cord in the axial plane (B). The gadolinium-enhanced MRI revealed enhancement in the peripheral white matter of the spinal cord (C and D), which is not common in NMOSD. Her brain MRI revealed multiple T2 HSI lesions in the white matter (E), external capsule of the basal ganglia, and splenium of the corpus callosum (F). Repeated assay for AQP4-Ab was negative. As her initial spinal cord biopsy did not reveal any malignant cells, she received an initial treatment of corticosteroid combined with plasmapheresis. She partially improved after the treatment, but nevertheless worsened again to develop quadriparesis. Her follow-up MRI revealed more extensive T2 HSI lesion (G) and gadolinium-enhancing lesions (H). 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lesion in the spinal cord (I). A second spinal cord biopsy diagnosed a primary CNS lymphoma.

A, B, and G = T2-weighted MRI; C, D, and H = T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium enhancement; E and F = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI; I = 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET).

Red line in A and blue line in D highlight the level where the axial images in B and C are taken, respectively.

AQP4-Ab, autoantibody against aquaporin 4; HSI, high signal intensity; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

CSF cytology (sensitivity of 2–32%),137 immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) rearrangement testing (sensitivity of 58% and specificity of 85%),138 and other molecular diagnostic testing may help with the diagnosis of CNS lymphoma to some extent. In differentiating CNS lymphoma from NMOSD, position emission tomography (PET) can play an important role as a non-invasive diagnostic tool (Figure 6).136 Nevertheless, histopathological confirmation using stereotactic or navigation-guided needle biopsy are recommended for the diagnostic confirmation of CNS lymphoma.139

Patients with LETM should be suspected of having primary CNS lymphoma if they continue to worsen, with or without partial initial improvement, despite the combined treatment of methylprednisolone and plasmapheresis, if they show persistent gadolinium enhancement after 3 months of onset, or if they have hypermetabolic lesions on FDG-PET. In patients who are highly suspected to have primary CNS lymphoma, corticosteroid treatment is generally avoided before the biopsy, because it might obscure the histopathological findings.139

Neuro-Behçet’s disease

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a multi-systemic vasculitis that can present as painful mucocutaneous lesions combined with diverse systemic involvement. Its prevalence is higher in the Middle East and Pacific Rim than in Western countries (420/100,000 in Turkey versus 5/100,000 in the US).140,141 Nervous system involvement (neuro-Behçet’s disease, NBD) can be found in a pooled average of 9.4% of BD patients, most of which involve the CNS rather than the peripheral nervous system.142 CNS involvement of NBD is categorized as either parenchymal (multifocal/diffuse, brainstem, spinal cord, cerebral, or optic nerve) or non-parenchymal (cerebral venous thrombosis, intracranial aneurysm, cervical aneurysm/dissection, or acute meningeal syndrome).143 A recent study showed that most (80%) of the spinal cord involvement of NBD was longitudinally extensive lesions, and thereby could resemble LETM of NMOSD144 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

NBD manifesting LETM and progressive brain atrophy.

A 25-year-old man who had been experiencing progressive emotional lability for 2 years presented with acute paraparesis. His spinal cord MRI revealed LETM involving the entire cervical and thoracic spine (A) and brain MR showed T2 HSI lesions in the cerebral white matter (B) and mild brainstem atrophy (C). He had recurrent oral ulcers, perianal ulcers, and acineform eruptions, and thereby was diagnosed with NBD. Despite combined treatment of corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide, his neurologic status worsened. In 6 months after the onset of myelitis, he became bed-ridden without any spontaneous speech. After treatment with infliximab he improved to be able to walk without assistance. His follow-up brain MRI in 4 years showed severe atrophy of the brainstem (D) and the cerebrum with moderate T2 HSI changes in the white matter (E).

A = T2-weighted MRI; B–E = fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI.

HSI, high signal intensity; LETM, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; NBD, neuro-Behçet’s disease.

The international study group for BD earlier proposed that the presence of oral ulcers plus two of the following four minor criteria are needed for the diagnosis of BD: genital ulcers, eye lesions, skin lesions, and positive pathergy test.145 Nevertheless, neurological manifestations in BD can sometimes precede its systemic manifestations, thereby delaying the proper diagnosis of NBD.146 Recently, two levels of diagnostic criteria for NBD – definite and probable NBD – were proposed in those without systemic manifestations.143

The distinctive features of NBD, from those of NMOSD, includes the presence of headache with or without meningoencephalitis (about 70%),142 a progressive course (38%),147 and severe brainstem/cerebral atrophy and/or leukoencephalopathy in brain MRI.148,149 Of note, as spinal cord involvement in NBD is considered a poor prognostic factor (60% of patients became dependent or died after a mean follow-up of 67 months),150 NBD patients mimicking NMOSD need careful monitoring and intensive treatment.

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula

Spinal dural arteriovenous fistula (SDAVF) is the most common type of vascular malformation in the spinal cord. It predominantly affects males in their fifth or sixth decades.151 The exact pathophysiology of SDAVF is not entirely clear, but a reduced arteriovenous pressure gradient followed by a decreased tissue perfusion of the spinal cord has been proposed to be causative.152 Patients with SDAVF mostly experience a subacute onset and progressive myelopathy with acute deteriorations of symptoms after exercise or prolonged rest.153 The spinal cord MRI of SDAVF generally reveals longitudinally extensive T2-hyperintense lesions, thereby mimicking LETM of NMOSD. The key radiological difference between SDAVF and LETM in NMOSD when present are the abnormal dilated intradural veins of the spinal cord on T2-weighted MRI (flow void) and/or serpentine enhancing vascular structures on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI, mostly in the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. However, these findings in conventional MRI may not be observed or easily differentiated from the normal vascular structures of the spinal cord, especially in the early stage of disease154,155 (Figure 8). Though some advocate the use of spinal MR angiography in the diagnosis of SDAVF,155 catheter angiography remains a diagnostic procedure of choice (Figure 8). SDAVF can be treated by either endovascular embolization or surgical ligation of the fistula.156

Figure 8.

Two cases of SDAVF.

Patient A (A and B), a 59-year-old male, presented with subacute quadriparesis that progressed to bed-ridden state over 4 months. On admission, his cervical spine MRI showed a typical signal void (arrowhead, A) and enhancing vascular structures (arrow, B) over the ventral surface of the cervical spine. He was diagnosed with SDAVF and was treated with embolization. Meanwhile, patient B (C – H), a 78-year-old male, presented with subacute progressive paraparesis over 18 months. His spinal MRI showed diffuse longitudinally extensive T2 HSI lesions in the thoracic spine without definite signal void (C and D), gadolinium enhancement of the spinal cord (E), and prominently enhanced vascular structures over the dorsal surface of the spinal cord (arrow, F). The spinal angiography of patient B, performed of the thoracic T8 spinal dorsal artery (G), showed a SDAVF and engorged/tortuous medullary veins (H). Note that the findings of conventional spinal MRI in patients with SDAVF can vary widely, therefore clinical suspicions are most important.

A, C, and D = T2-weighted MRI; B, E, and F = T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium enhancement; G and H = spinal angiography.

HSI, high signal intensity; SDAVF, spinal dural arteriovenous fistula; T8, thoracic vertebrae 8.

Infections

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum (T. pallidum). If not properly treated, this infectious disease can progress through four stages of primary (penetration of the T. pallidum, 10–90 days), secondary (hematogeneous dissemination of the T. pallidum, 4–10 weeks), latent (asymptomatic, up to decades), and tertiary syphilis (localized granuloma or severe diffuse inflammation involving cardiovascular organs or CNS).157–159

Although optic nerve involvement by syphilis (neurosyphilis-optic neuritis) is relatively uncommon, it causes bilateral severe visual loss and pain that can mimic NMOSD-optic neuritis. It can present in any four stages of syphilis and its mode of onset can be variable, as acute, subacute, or chronic progressive.160–163

Some neurosyphilis-optic neuritis cases can manifest as optic perineuritis rather than optic neuritis, especially in the early stages, with constricted visual fields and preserved central vision, an atypical pattern for NMOSD-optic neuritis (Figure 9).162,163 As this neurosyphilis-optic neuritis requires specific treatment, screening for neurosyphilis is important in bilateral optic neuritis cases with poor response to steroid, positive serum treponemal test, history of untreated syphilis, HIV infection and/or constricted pattern of visual field defect.

Figure 9.

Bilateral optic neuropathy in neurosyphilis.

A 34-year-old man experienced subacute, progressive visual loss. In 3 months he became blind in his right eye and his left vision became blurred, combined with a visual field defect. The orbit MRI revealed a diffuse T2 HSI in the right optic nerve (arrow) and also moderate T2 HSI in the left optic nerve (arrow head) (A and B). The cerebrospinal fluid revealed pleocytosis, increased level of protein, positive venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test results. After treatment with intravenous penicillin, his constricted visual field in the left eye, which represented a pattern of perineuritis (C) improved over one month (D).

A and B = T2-weighted image, C and D = Humphrey perimetry.

HSI, high signal intensity.

Neurosyphilis can also rarely manifest as a form of LETM that should be treated by intravenous penicillin.164

Miscellaneous infections

Though rare, infections such as herpes virus (Herpes simplex,165 Epstein–Barr virus,166 and cytomegalovirus167), human T-lymphotrophic virus 1 (HTLV-1),168 dengue virus,169 Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme),170 tuberculosis,171 Mycoplasma pneumoniae,172 and Streptococcus pneumoniae15 can manifest as LETM and/or optic neuritis.

The differential diagnosis of infectious LETM from NMOSD-LETM can sometimes be challenging as some NMOSD cases can show high pleocytosis.17 Nevertheless, infectious myelitis can differ from NMOSD-LETM, in that the former can have either fever with high C-reactive protein/low CSF glucose level (bacterial), history of pulmonary tuberculosis with low CSF adenosine deaminase level (tuberculosis), chronic progressive course (HTLV-1), presence of the skin lesion, or diffuse arthralgia (miscellaneous). Moreover, AQP4-Ab is not detected in the sera of patients with most of the infectious myelitis. If infectious etiology were suspected in patients with LETM, further evaluations including culture of the specific infectious agents, PCR analysis, and serology for the specific infectious agent are needed. If bacterial LETM cannot be ruled out in the initial diagnostic phase (with AQP4-Ab serostatus unavailable), antibiotics and steroid may be administered according to the management of bacterial meningitis, pending the AQP4-Ab serostatus.

Interestingly, though most of the infectious myelitis cases reported absence of AQP4-Ab,15,166–173 several cases have shown that NMOSD with AQP4 can develop several days after zoster infection.174–176 These findings might imply at least some pathogenic overlap between these two distinctive diseases of NMOSD and herpes zoster.

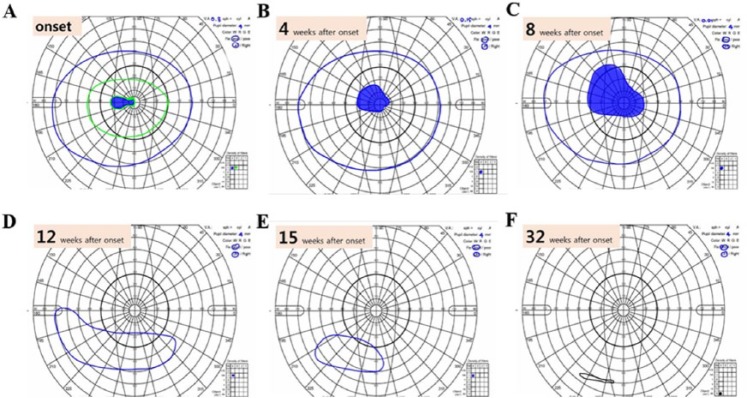

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is an inherited optic neuropathy caused by mutations in the mitochondrial DNA (the three most common mitochondrial mutations in LHON are at nucleotide positions 11778, 14484, and 3460).177 It predominantly affects males (80%) in their second or third decade of life and is probably one of the most common hereditary optic neuropathies, with a prevalence of more than 3.22 per 100,000 in northeast England.178 Although it is an inherited disease, only about 40% of LHON patients are aware of their family member having symptoms of LHON, which could be attributable to the low penetrance of LHON (only 27% in males and 8% in females).179 It mostly manifests as bilateral simultaneous or consecutive painless central scotoma that progress to visual loss over weeks or months (Figure 10). Currently, there is no established treatment for LHON and most patients are left with bilateral visual acuities ⩽20/200.180 The major difference compared to NMOSD-optic neuritis is the male predominance, more progressive course, more bilateral optic nerve involvement from onset, presence of a family history, absence of gadolinium enhancement in the optic nerve on MRI, absence of the response to immune-modulating/suppressing treatment, and mutations in the mitochondrial DNA. Interestingly, some patients with LHON can have systemic involvement beyond the optic nerve (LHON-plus), including the brain and the spinal cord, just like the CNS lesions seen in MS. A recent report suggested that the spinal cord involvement of LHON-plus could be distinctive from that of NMOSD in that the former involved predominantly the posterior column of the spinal cord.181

Figure 10.

Progressive visual field defect in a patient with LHON.

A 46-year-old man had painless subacute visual loss to hand perception only in his right eye over 6 months. Eight months from symptom onset, his left eye developed a central scotoma (A) which gradually enlarged over 8 months (B–F). After two years from symptom onset, his visual acuity in the right and left eyes were hand perception and light perception, respectively. His genetic testing for LHON revealed the pathologic mitochondrial DNA 11778 (GA) point mutation.

A–F = Goldmann perimetry.

LHON, Leber hereditary optic neuropathy.

Conclusion

Diverse neurological diseases including inflammatory, infectious, malignant, vascular, and hereditary etiologies can resemble the phenotypes of NMOSD. Nevertheless, as these NMOSD-mimics are distinct from NMOSD in treatment as well as pathophysiology, early differential diagnosis and appropriate individualized treatment will improve the outcome of such patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Chihiro Ono for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (#26293205), by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labor of Japan, and by grant No. 2014R1A1A2055741 from the Korea National Research foundation fund.

Conflict of interest statement: Prof. Kazuo Fujihara serves on scientific advisory boards for Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen Idec, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Novartis Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Nihon Pharmaceutical, Merck Serono, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Medimmune and Medical Review; has received funding for travel and speaker honoraria from Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen Idec, Eisai Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Novartis Pharma, Astellas Pharma Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Daiichi Sankyo, and Nihon Pharmaceutical; serves as an editorial board member of Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology (2009 to present) and an advisory board member of the Sri Lanka Journal of Neurology; has received research support from Bayer Schering Pharma, Biogen Idec Japan, Asahi Kasei Medical, The Chemo-Sero-Therapeutic Research Institute, Teva Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Nihon Pharmaceutical, and Genzyme Japan.

Contributor Information

Sung-Min Kim, Department of Neurology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Seong-Joon Kim, Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Haeng Jin Lee, Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University, College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Hiroshi Kuroda, Department of Neurology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan.

Jacqueline Palace, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Kazuo Fujihara, Department of Neurology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Japan Department of Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics, Fukushima Medical University School of Medicine, and MS & NMO Center, Southern TOHOKU Research Institute for Neuroscience (STRINS), Koriyama 963-8563, Japan.

References

- 1. Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015; 85: 177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flanagan E, Cabre P, Weinshenker B, et al. Epidemiology of aquaporin-4 autoimmunity and neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Ann Neurol. Epub ahead of print 17 February 2016. DOI: 10.1002/ana.24617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wingerchuk D. Neuromyelitis optica: effect of gender. J Neurol Sci 2009; 286: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitley J, Leite M, Nakashima I, et al. Prognostic factors and disease course in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from the United Kingdom and Japan. Brain 2012; 135: 1834–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim SM, Waters P, Woodhall M, et al. Gender effect on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder with aquaporin4-immunoglobulin G. Mult Scler. Epub ahead of print 19 October 2016. DOI: 10.1177/1352458516674366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim SM, Waters P, Vincent A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid/serum gradient of IgG is associated with disability at acute attacks of neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol 2011; 258: 2176–2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2004; 364: 2106–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wingerchuk D, Lennon V, Lucchinetti C, et al. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canellas AR, Gols AR, Izquierdo JR, et al. Idiopathic inflammatory-demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system. Neuroradiol 2007; 49: 393–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trebst C, Raab P, Voss E, et al. Longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis: it’s not all neuromyelitis optica. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7: 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pittock S, Lennon V, Bakshi N, et al. Seroprevalence of aquaporin-4-IgG in a northern California population representative cohort of multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 1433–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waters P, Reindl M, Saiz A, et al. Multicentre comparison of a diagnostic assay: aquaporin-4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 1005–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waters PJ, Pittock SJ, Bennett JL, et al. Evaluation of aquaporin-4 antibody assays. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol 2014; 5: 290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim SM, Waters P, Woodhall M, et al. Utility of aquaporin-4 antibody assay in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sato D, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto M, et al. Seronegative neuromyelitis optica spectrum: the challenges on disease definition and pathogenesis. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 2014; 72: 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Devic E. Myélite subaiguë compliquée de névrite optique. Bull Méd 1894; 8: 1033–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, et al. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology 1999; 53: 1107–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, et al. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med 2005; 202: 473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pittock S, Weinshenker B, Lucchinetti C, et al. Neuromyelitis optica brain lesions localized at sites of high aquaporin 4 expression. Arch Neurol 2006; 63: 964–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006; 66: 1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jarius S, Wildemann B. Aquaporin-4 antibodies (NMO-IgG) as a serological marker of neuromyelitis optica: a critical review of the literature. Brain Pathol 2013; 23: 661–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Waters P, McKeon A, Leite M, et al. Serologic diagnosis of NMO: a multicenter comparison of aquaporin-4-IgG assays. Neurology 2012; 78: 665–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang J, Kim SM, Kim YJ, et al. Accuracy of the fluorescence-activated cell sorting assay for the aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4-Ab): comparison with the commercial AQP4-Ab assay kit. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0162900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiao Y, Fryer JP, Lennon VA, et al. Updated estimate of AQP4-IgG serostatus and disability outcome in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2013; 81: 1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoftberger R, Sabater L, Marignier R, et al. An optimized immunohistochemistry technique improves NMO-IgG detection: study comparison with cell-based assays. PLoS One 2013; 8: e79083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim W, Lee J, Li X, et al. Quantitative measurement of anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using purified recombinant human aquaporin-4. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takahashi T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, et al. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibody is involved in the pathogenesis of NMO: a study on antibody titre. Brain 2007; 130: 1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujihara K, Sato DK. AQP4 antibody serostatus: is its luster being lost in the management and pathogenesis of NMO? Neurology 2013; 81: 1186–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marignier R, Bernard-Valnet R, Giraudon P, et al. Aquaporin-4 antibody-negative neuromyelitis optica: distinct assay sensitivity-dependent entity. Neurology. 2013; 80: 2194–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen M, De Sèze J, Marignier R, et al. False positivity of anti aquaporin-4 antibodies in natalizumab-treated patients. Mult Scler 2016; 22: 1231–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Compston A, Wekerle H, McDonald I. Chapter 5 The origin of multiple sclerosis: a synthesis. In: Compston A, Confavreux C, Lassmann H, et al. (eds) McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis, 4th ed. 2006. Edingburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wingerchuk D, Pittock S, Lucchinetti C, et al. A secondary progressive clinical course is uncommon in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2007; 68: 603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Palace J, Leite M, Nairne A, et al. Interferon Beta treatment in neuromyelitis optica: increase in relapses and aquaporin 4 antibody titers. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 1016–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shimizu J, Hatanaka Y, Hasegawa M, et al. IFNβ-1b may severely exacerbate Japanese optic-spinal MS in neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Neurology 2010; 75: 1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Min J, Kim B, Lee K. Development of extensive brain lesions following fingolimod (FTY720) treatment in a patient with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kleiter I, Hellwig K, Berthele A, et al. Failure of natalizumab to prevent relapses in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barnett M, Prineas J, Buckland M, et al. Massive astrocyte destruction in neuromyelitis optica despite natalizumab therapy. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gelfand JM, Cotter J, Klingman J, et al. Massive CNS monocytic infiltration at autopsy in an alemtuzumab-treated patient with NMO. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2014; 1: e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jarius S, Wildemann B, Paul F. Neuromyelitis optica: clinical features, immunopathogenesis and treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 176: 149–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Asgari N, Lillevang S, Skejoe H, et al. A population-based study of neuromyelitis optica in Caucasians. Neurology 2011; 76: 1589–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bentzen J, Flachs E, Stenager E, et al. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Denmark 1950–2005. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mayr W, Pittock S, McClelland R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1985–2000. Neurology 2003; 61: 1373–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cossburn M, Tackley G, Baker K, et al. The prevalence of neuromyelitis optica in South East Wales. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Husson B, et al. ; Neuropediatric KIDSEP Study Group of the French Neuropediatric Society. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis cohort study: prognostic factors for relapse. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2007; 11: 90–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ochi H, Fujihara K. Demyelinating diseases in Asia. Curr Opin Neurol 2016; 29: 222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miyamoto K. Epidemiology of neuromyelitis optica. Nihon Rinsho 2015; 73(Suppl. 7): 260–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim S, Kim W, Li X, et al. Clinical spectrum of CNS aquaporin-4 autoimmunity. Neurology 2012; 78: 1179–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Koch-Henriksen N, Sorensen PS. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 520–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti CF. Comparative immunopathogenesis of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica, and multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol 2007; 20: 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nakajima H, Hosokawa T, Sugino M, et al. Visual field defects of optic neuritis in neuromyelitis optica compared with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2010; 10: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Merle H, Olindo S, Bonnan M, et al. Natural history of the visual impairment of relapsing neuromyelitis optica. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 810–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wingerchuk DM. Neuromyelitis optica: current concepts. Front Biosci 2004; 9: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim SM, Go MJ, Sung JJ, et al. Painful tonic spasm in neuromyelitis optica: incidence, diagnostic utility, and clinical characteristics. Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 1026–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Apiwattanakul M, Popescu B, Matiello M, et al. Intractable vomiting as the initial presentation of neuromyelitis optica. Ann Neurol 2010; 68: 757–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Misu T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, et al. Intractable hiccup and nausea with periaqueductal lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2005; 65: 1479–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Banwell B, Tenembaum S, Lennon V, et al. Neuromyelitis optica-IgG in childhood inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorders. Neurology 2008; 70: 344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: an international update. Neurology 2015; 84: 1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yonezu T, Ito S, Mori M, et al. “Bright spotty lesions” on spinal magnetic resonance imaging differentiate neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ito S, Mori M, Makino T, et al. “Cloud-like enhancement” is a magnetic resonance imaging abnormality specific to neuromyelitis optica. Ann Neurol 2009; 66: 425–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nakamura M, Misu T, Fujihara K, et al. Occurrence of acute large and edematous callosal lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Matthews L, Marasco R, Jenkinson M, et al. Distinction of seropositive NMO spectrum disorder and MS brain lesion distribution. Neurology 2013; 80: 1330–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim SM, Kim JS, Heo YE, et al. Cortical oscillopsia without nystagmus, an isolated symptom of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder with anti-aquaporin 4 antibody. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Magana SM, Matiello M, Pittock SJ, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2009; 72: 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, Krecke K, et al. Brain abnormalities in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol 2006; 63: 390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Calabrese M, Oh M, Favaretto A, et al. No MRI evidence of cortical lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2012; 79: 1671–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Storoni M, Davagnanam I, Radon M, et al. Distinguishing optic neuritis in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease from multiple sclerosis: a novel magnetic resonance imaging scoring system. J Neuroophthalmol 2013; 33: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lim Y, Pyun S, Lim H, et al. First-ever optic neuritis: distinguishing subsequent neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci 2014; 35: 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Khanna S, Sharma A, Huecker J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of optic neuritis in patients with neuromyelitis optica versus multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol 2012; 32: 216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liu Y, Wang J, Daams M, et al. Differential patterns of spinal cord and brain atrophy in NMO and MS. Neurology 2015; 84: 1465–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bergamaschi R, Tonietti S, Franciotta D, et al. Oligoclonal bands in Devic’s neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: differences in repeated cerebrospinal fluid examinations. Mult Scler 2004; 10: 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jarius S, Franciotta D, Bergamaschi R, et al. Polyspecific, antiviral immune response distinguishes multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79: 1134–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schneider E, Zimmermann H, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. Optical coherence tomography reveals distinct patterns of retinal damage in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bennett J, de Sèze J, Lana-Peixoto M, et al. Neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis: seeing differences through optical coherence tomography. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lucchinetti C, Mandler R, McGavern D, et al. A role for humoral mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. Brain 2002; 125: 1450–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Misu T, Fujihara K, Kakita A, et al. Loss of aquaporin 4 in lesions of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Brain 2007; 130: 1224–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Roemer S, Parisi J, Lennon V, et al. Pattern-specific loss of aquaporin-4 immunoreactivity distinguishes neuromyelitis optica from multiple sclerosis. Brain 2007; 130: 1194–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Misu T, Hoftberger R, Fujihara K, et al. Presence of six different lesion types suggests diverse mechanisms of tissue injury in neuromyelitis optica. Acta Neuropathol 2013; 125: 815–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Confavreux C, Vukusic S, Moreau T, et al. Relapses and progression of disability in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1430–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cree BA, Gourraud P, Oksenberg JR, et al. ; University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol 2016; 80: 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cree BA, Khan O, Bourdette D, et al. Clinical characteristics of African Americans vs Caucasian Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004; 63: 2039–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2013; 81: 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. de Sèze J, Debouverie M, Zephir H, et al. Acute fulminant demyelinating disease: a descriptive study of 60 patients. Arch Neurol 2007; 64: 1426–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Krupp L, Tardieu M, Amato M, et al. International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: revisions to the 2007 definitions. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 1261–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Koelman D, Chahin S, Mar S, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in 228 patients: a retrospective, multicenter US study. Neurology 2016; 86: 2085–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tenembaum S, Chamoles N, Fejerman N. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a long-term follow-up study of 84 pediatric patients. Neurology 2002; 59: 1224–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Khong PL, Ho HK, Cheng PW, et al. Childhood acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: the role of brain and spinal cord MRI. Pediatr Radiol 2002; 32: 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Dale R, de Sousa C, Chong W, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis in children. Brain 2000; 123: 2407–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhang L, Wu A, Zhang B, et al. Comparison of deep gray matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging among adults with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, and neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hyun J, Jeong I, Joung A, et al. Evaluation of the 2015 diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology 2016; 86: 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tillema J, Pirko I. Neuroradiological evaluation of demyelinating disease. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2013; 6: 249–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology 2016; 87: S38–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. McKeon A, Lennon V, Lotze T, et al. CNS aquaporin-4 autoimmunity in children. Neurology 2008; 71: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology 2002; 59: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sato D, Nakashima I, Takahashi T, et al. Aquaporin-4 antibody-positive cases beyond current diagnostic criteria for NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2013; 80: 2210–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Flanagan EP, Weinshenker BG, Krecke KN, et al. Short myelitis lesions in aquaporin-4-IgG-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72: 81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Qiu W, Wu JS, Zhang MN, et al. Longitudinally extensive myelopathy in Caucasians: a West Australian study of 26 cases from the Perth Demyelinating Diseases Database. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010; 81: 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gajofatto A, Monaco S, Fiorini M, et al. Assessment of outcome predictors in first-episode acute myelitis: a retrospective study of 53 cases. Arch Neurol 2010; 67: 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kim SM, Waters P, Woodhall M, et al. Characterization of the spectrum of Korean inflammatory demyelinating diseases according to the diagnostic criteria and AQP4-Ab status. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kim J, Park Y, Kim S, et al. A case of chronic progressive myelopathy. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 1255–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Okai A, Muppidi S, Bagla R, et al. Progressive necrotizing myelopathy: part of the spectrum of neuromyelitis optica? Neurol Res 2006; 28: 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Optic Neuritis Study Group. The clinical profile of optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109: 1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Beck R, Cleary P, Backlund J. The course of visual recovery after optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 1771–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Beck R, Cleary P. Optic neuritis treatment trial: one-year follow-up results. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill: 1960). 1993; 111: 773–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Matiello M, Lennon V, Jacob A, et al. NMO-IgG predicts the outcome of recurrent optic neuritis. Neurology 2008; 70: 2197–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Optic Neuritis Study Group. Multiple sclerosis risk after optic neuritis: final optic neuritis treatment trial follow-up. Arch Neurol 2008; 65: 727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kim SM, Woodhall MR, Kim JS, et al. Antibodies to MOG in adults with inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015; 2: e163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Kleiter I, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 1: frequency, syndrome specificity, influence of disease activity, long-term course, association with AQP4-IgG, and origin. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Petzold A, Wattjes M, Costello F, et al. The investigation of acute optic neuritis: a review and proposed protocol. Nat Rev Neurol 2014; 10: 447– 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Pham-Dinh D, Mattei M, Nussbaum J, et al. Myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein is a member of a subset of the immunoglobulin superfamily encoded within the major histocompatibility complex. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993; 90: 7990–7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Berger T, Rubner P, Schautzer F, et al. Antimyelin antibodies as a predictor of clinically definite multiple sclerosis after a first demyelinating event. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kuhle J, Pohl C, Mehling M, et al. Lack of association between antimyelin antibodies and progression to multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. O’Connor KC, McLaughlin KA, De Jager PL, et al. Self-antigen tetramers discriminate between myelin autoantibodies to native or denatured protein. Nat Med 2007; 13: 211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Waters P, Woodhall M, O’Connor K, et al. MOG cell-based assay detects non-MS patients with inflammatory neurologic disease. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2015; 2: e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ramanathan S, Dale R, Brilot F. Anti-MOG antibody: the history, clinical phenotype, and pathogenicity of a serum biomarker for demyelination. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15: 307–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sato DK, Callegaro D, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2014; 82: 474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Kitley J, Woodhall M, Waters P, et al. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in adults with a neuromyelitis optica phenotype. Neurology 2012; 79: 1273–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Baumann M, Hennes E, Schanda K, et al. Children with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and antibodies to the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG): extending the spectrum of MOG antibody positive diseases. Mult Scler 2016; 22: 1821–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Jarius S, Kleiter I, Ruprecht K, et al. MOG-IgG in NMO and related disorders: a multicenter study of 50 patients. Part 3: brainstem involvement-frequency, presentation and outcome. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Rybicki B, Major M, Popovich J, Jr, et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145: 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, et al. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol 1985; 42: 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Flanagan EP, Kaufmann TJ, Krecke KN, et al. Discriminating long myelitis of neuromyelitis optica from sarcoidosis. Ann Neurol 2016; 79: 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kidd DP, Burton BJ, Graham EM, et al. Optic neuropathy associated with systemic sarcoidosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016; 3: e270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3: 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Wegener S, Linnebank M, Martin R, et al. Clinically isolated neurosarcoidosis: a recommended diagnostic path. Eur Neurol 2015; 73: 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]