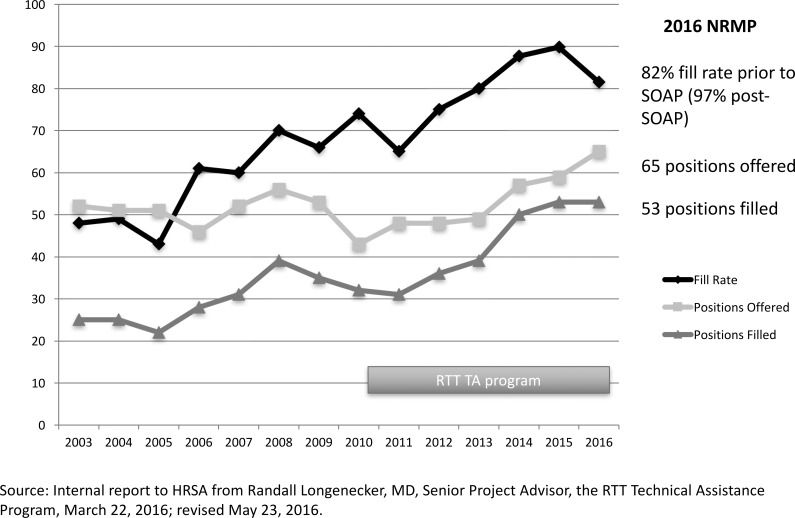

In the past decade, rural training tracks (RTTs) have become increasingly prominent in the lexicon of public discourse and policy around graduate medical education (GME). RTT Technical Assistance grant program Match data for 2010–2016 demonstrate increasing student interest (Figure). Although public data are not yet available as to their number, rural tracks are developing in specialties other than family medicine. There remains, however, confusion around the terms RTT and rural program due to the lack of definition in the accreditation process and in federal and state statute. Medical students want to know, developing programs want to know, and communities and legislators want to know: “What is a rural program?”

Figure.

1-2 RTT Match Trends 2003–2016

Note: Abbreviations: NRMP, National Resident Matching Program; SOAP, Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program; HRSA, Health Resources and Services Administration.

As a national nonprofit cooperative of rural programs of various types, including RTTs, the RTT Collaborative is committed to sustaining health professions education and training in rural places, and its work hinges on clear definitions. Definitions are relevant to program development and financing, and to good policy.

This perspective outlines the history of rural program definitions and proposes a consistent nomenclature for the GME community.

Background

For more than 50 years, family medicine residency programs in rural places have defined themselves in various ways. However, until RTTs emerged in the mid-1980s, and the Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999 incorporated them into statute, the rurality of a program was not a matter of accreditation or finance.

There is good evidence regardless of program definition that the more time spent training in a rural place, the greater the likelihood of graduate placement in rural community practice.1,2 In 1986, Robert Maudlin and others recognized the importance of this “training in place,” and established rural training tracks to increase the number of graduates going into rural practice.3 Commonly referred to as a prototypical “1-2 RTT,” with 1 year of training in a large, urban residency program generally followed by 2 years in a rural community, this model was implemented over the subsequent decade. Given their geographic distance from an associated urban partner, and deviation from the minimum complement of 4 residents per training year, these programs were considered novel and recognized as such by the Review Committee for Family Medicine (RC-FM).

RTTs grew in number and were recognized as a legitimate configuration for residency training by the mid-1990s. To ensure quality and promote sustainability, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the RC-FM established conditions for alternative tracks in the “1-2 format.” The RC-FM also defined a supplementary application process that eventually incorporated some of the conditions for alternative tracks. However, RTTs were expected to substantially comply with the requirements common to all accredited residency programs in family medicine, and were not assigned a separate category of accreditation, other than a notation as to their 1-2 format.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 capped funding for GME positions in the United States in anticipation of a physician surplus, a prediction that did not apply to rural communities. This act was revised in 1999 to allow an urban program to increase its cap (up to a “rural FTE limitation”) if it participated with a rural hospital in implementing a new “accredited rural training track” or an “integrated rural training track.” Subsequent regulations left the definition of an accredited RTT up to the accrediting body, but acknowledged that programs in the 1-2 format met this definition. Rural was not defined, and the definition for an “integrated” RTT did not exist until the Fiscal Year (FY) 2014 Final Rule, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) defined it in regulation as a separately accredited residency program where residents spend at least 50% of their training in a rural location.4

Other than clarifying the meaning of a “new program” (FY 2010), establishing rules around GME payment with the reclassification of a “rural” to an “urban” hospital (FY 2015), and revising the cap rules for rural hospitals (FY 2017), little has officially changed in either accreditation or regulation of RTTs since 2004. In practice, rural programs remain publicly undefined by the RC-FM. Currently, the only formal reference to the 1-2 format in ACGME documents appears in the application form for family medicine (updated August 2015). An applicant program desiring to use this format is asked to explain the planned curriculum (ie, how resident experiences at the alternative site in years 2 and 3 complement the experiences in year 1), and where the curriculum for the residents in the alternative track differs from the core program.

A Proposed Nomenclature

For the RTT Collaborative, the rurality of a program is more than a matter of accreditation or finance alone, and is critically relevant to the preparation of a quality rural physician workforce. Therefore, the RTT Collaborative Board, after careful analysis and thoughtful review, adopted the following definition for rural residency training and proposes the nomenclature below to be used by others.

A rural program is an accredited residency program, in which residents spend the majority of their time (more than 50%, as reported to CMS and/or the Teaching Health Center program) training in a rural place.4 Rural place is defined as a nonmetropolitan county or any census tract or zip code identified as rural by any 2 federally accepted definitions.5,6 The program location in family medicine is the street address of the primary family medicine practice center where residents meet the American Board of Family Medicine continuity requirement. The location of a rural program in specialties other than family medicine will need to be adapted to the individual specialties' requirements.

An integrated rural training track (IRTT) is a subtype of rural program that is separately accredited, and because of its generally smaller size and variable resources, is substantially integrated with a larger, often more urban, residency program.

Integrated in a substantive way

Rurally located and rurally focused

Engaged in training and/or education: residency ± medical school experiences

Deliberately structured as an explicit track or pathway

For the purpose of this definition, substantial integration means (1) structured interaction among the residents of both the IRTT and the larger affiliated program; (2) some sharing of faculty and/or program director; (3) shared didactics and/or scholarly activity; and (4) at least 4 months of structured curriculum shared by residents of both programs. Separate accreditation ensures rigor in meeting the standards of accreditation on one hand, yet flexibility in meeting the unique small scale of these programs on the other, while integration ensures sustainability and excellence. All existing rurally located 1-2 RTTs fall under this definition.

Governance also deserves mentioning in any discussion of rural program definition, even though defining this in clear terms is beyond the scope of this perspective. For a residency program to be truly recognized and sustained as a rural program, there needs to be substantial evidence of program governance anchored in the rural location. If, for example, the program director of an IRTT is not located in the rural place, then affiliation agreements between participating and sponsoring institutions should clearly outline a decision-making process that appropriately empowers the rural community. Otherwise “integration” easily becomes “absorption,” and an IRTT could become a rural program in name only, or cease to be a program at all.

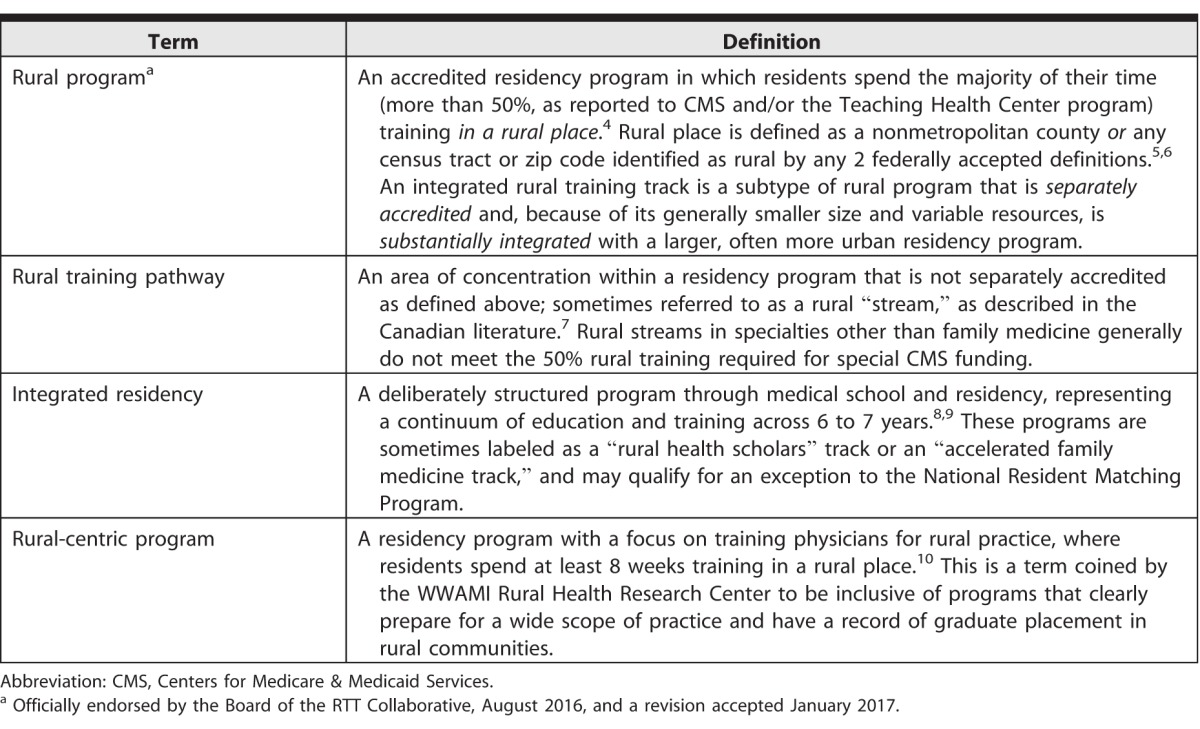

In addition to these proposed definitions, other terms and phrases have been used in the literature and in common parlance that do not carry a widely accepted definition and may create confusion (Table). Any of these programs, whether or not they are separately accredited, can, and often do, choose to register for and receive a separate National Resident Matching Program number for the purpose of targeted recruitment. There are also rurally located programs in other specialties to which any of these definitions could apply, and currenly there are developing programs described as rural tracks in internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and surgery. How the proposed nomenclature for rural programs will be addressed in the program requirements for any specialty has yet to be determined.

Table.

Proposed Rural Residency Program Nomenclature 2017

Summary

Even if accrediting bodies or legislators and regulators do not agree on a universal definition, the RTT Collaborative is implementing and promoting at least 1 definition for widespread use. The collaborative will continue to foster the development of rural programs, track them, and support them, using its own definitions and proposing that these definitions be used in consistent ways by others. Rural residency programs in large rural communities or tracks and pathways adapted to the capacity of small rural communities will be encouraged. The sustainability of rural programs will remain the focus of efforts to improve the finance and governance of GME—ever in pursuit of a high-quality and larger rural workforce.

References

- 1. Bowman RC, Penrod JD. . Family practice residency programs and the graduation of rural family physicians. Fam Med. 1998; 30 4: 288– 292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patterson DG, Schmitz D, Longenecker R, et al. . Family medicine rural training track residencies: 2008–2015 graduate outcomes. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/02/RTT_Grad_Outcomes_PB_2016.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenthal TC, Maudlin RK, Sitorius, M, et al. . Rural training tracks in 4 family medicine residencies. Acad Med. 1992; 67 10: 685– 691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Aligns with CMS FY2004 regulations defining an integrated rural training track. Fed Regist. 2003; 68 148: 45645– 45672. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2003-08-01/pdf/03-19363.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rural Health Information Hub. Am I Rural?: tool. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/am-i-rural. Accessed March 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural classifications overview. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications.aspx. Accessed March 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krupa LK, Chan BT. . Canadian rural family medicine training programs: growth and variation in recruitment. Can Fam Physician. 2005; 51: 852– 853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abramson SB, Jacob D, Rosenfeld M, et al. . A 3-year MD—accelerating careers, diminishing debt. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369 12: 1085– 1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petrany SM, Crespo R. . The accelerated residency program: the Marshall University family practice 9-year experience. Fam Med. 2002; 34 9: 669– 672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patterson DG, Andrilla CHA, Schmitz D, et al. . Outcomes of rural-centric residency training to prepare family medicine physicians for rural practice. http://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/03/RHRC_PB158_Patterson.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]