Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine how relational qualities, including commitment to a sexual partner, are associated with condom use among young heterosexual adults at increased risk for sexually transmitted infections. Guided by the investment model of commitment processes, we hypothesized that sexual partner commitment is a function of satisfaction with, alternatives to, and investments in the relationship. Commitment to a sexual partner is, in turn, associated with reduced perceptions of vulnerability to sexually transmitted infection acquisition, which results in lowered condom use intentions and use.

METHOD

We tested the hypothesized model using data from [study name blinded for review], a four-wave, one-year longitudinal study featuring a Time 1 sample of 538 African American, Hispanic, and White young adult from East Los Angeles, California, who provided data on all their sexual relationships over the year.

RESULTS

Findings from hierarchical path models supported the hypotheses, with relational qualities significantly linked to condom use via commitment, perceived vulnerability to harm from partner and intentions to use.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings have implications for improving the health of high-risk individuals, including suggesting the importance of raising awareness of relational qualities that may give rise to unsafe sexual practices.

Keywords: condom use, intentions, perceived vulnerability, relationship commitment, investment model

Reducing condomless sexual intercourse among those at risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is a public health priority. Heterosexual contact is a significant exposure category for newly diagnosed AIDS cases in the U.S. [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2012]. Other STIs more common than HIV (e.g., chlamydia, human papillomavirus; CDC, 2014) are also of concern, with untreated STIs facilitating HIV transmission (e.g., Sexton, Garnett, & Rottingen, 2005).

Despite the fact that HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is recommended for certain risk groups (CDC, 2014) and new HIV/STI prevention technologies are under development (Thurman, Clark, & Doncel, 2011), condoms are the only widely available, effective method for preventing STIs for sexually active individuals. Decision-making regarding STI and HIV/AIDS prevention, including whether or not to use condoms, occurs in the context of a sexual relationship. The decisions individuals make regarding condom use, therefore, may best be understood in light of the qualities of the sexual relationship itself. The current research focused on understanding relationship qualities, as perceived by involved individuals, and their associations with condom use.

Sexual Behavior Occurs Within a Relational Context

The need to focus on relationship qualities when investigating sexual decision-making and behavior is increasingly clear. Much of the sexual behavior that puts individuals at risk for negative health outcomes is relational in nature, involving what transpires between two people (Jiwatram-Negro´n & El-Bassel, 2014). Understanding condom use, a key protective behavior, requires an understanding of the relational underpinnings of this activity (cf. Agnew, 1999; Lewis, McBride, Pollak, Puleo, Butterfield, & Emmons, 2006). Despite the relational nature of condom use, most theories that have been applied to understanding the determinants of it have not focused on relationship qualities. The predominant theoretical models used in understanding condom use for HIV/STI prevention [i.e., health belief model (Becker, 1974); theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980); social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1994); stages of change model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984); AIDS risk reduction model (Catania, Kegeles, & Coates, 1992)], even those that have informed community interventions (Mantell, DiVittis, & Auerback, 1997) do not capture important aspects of the relationships in which condom use occurs.

Research has begun to investigate the association of relationship characteristics and partnerships on condom use. For example, consistent condom use has been associated with the general quality of the relationship and coital frequency (Katz, Fortenberry, Zimet, Blythe, & Orr, 2000; Manning, Giordano, Longmore, & Flanigan, 2012). Moreover, recent studies have found that condoms are used primarily in casual relationships and use declines in relationships over time (Manlove et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the role of relationship qualities in sexual risk behavior has only begun to be examined (see Burton, Darbes, Operario, 2010; VanderDrift, Agnew, Harvey, & Warren, 2013). What is needed is a more thorough theory-based understanding of how relationship qualities influence condom use (cf. Karney, Hops, Redding, Reis, Rothman, & Simpson, 2010; Lewis, McBride, Pollak, Puleo, Butterfield, & Emmons, 2006).

Investment Model of Commitment Adapted for Understanding Condom Use

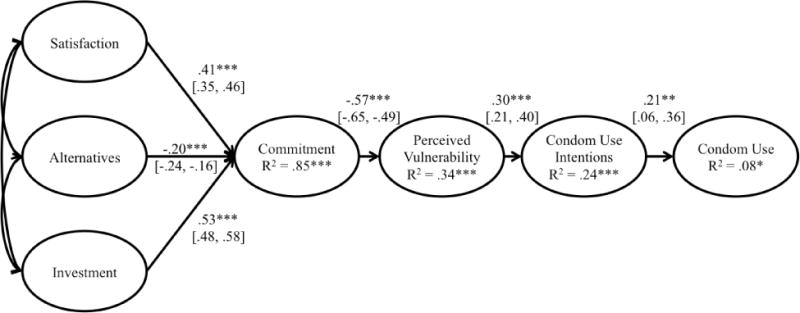

The theoretical framework guiding the current research is illustrated in Figure 1 and centers on the role of relationship commitment to a sexual partner. The term commitment is often used to describe the likelihood that an involvement will persist (Agnew, 2009). One particular theoretical model of commitment that has fueled research within social psychology and allied fields is the investment model of commitment processes (Rusbult, 1980; Rusbult, Agnew, & Arriaga, 2012). The accumulated empirical support for the investment model in various interpersonal contexts suggests that the model can increase not only our understanding of the factors underlying decisions to stay with (or leave) a given sexual partner, but also can guide thinking regarding the consequences of commitment for condom use.

Figure 1.

Investment Model of Commitment Processes Adapted for Understanding Condom Use. Path values are standardized estimates (betas), with 95% confidence intervals indicated in brackets, controlling for gender, race, and relationship duration. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Theoretically grounded within interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), the investment model examines the processes by which individuals come to be committed to a partner. Commitment, characterized by an intention to remain in a relationship, a psychological attachment to a partner, and a long-term orientation toward the partnership (Arriaga & Agnew, 2001; Rusbult & Buunk, 1993) is determined by (a) the amount of satisfaction that one derives from a relationship, (b) possible alternatives to that relationship, and (c) the investments one has made in the relationship.

Satisfaction level is the subjective evaluation of the relative positivity or negativity that one experiences in a relationship. If a person perceives that a particular sexual relationship is highly satisfying, the person is likely to be more committed to that relationship and less likely to discontinue it. Quality of alternatives to the current relationship also influences commitment, as perceiving that an attractive alternative will provide superior outcomes to a current relationship can lead one toward that alternative and away from the current relationship. Investment size also contributes to the stability of a partnership. If a person has made considerable investments in a particular sexual relationship (e.g., time and effort, disclosure of personal information), that person will be more likely to remain in the relationship than would a person with fewer investments. Individually and collectively, satisfaction, alternatives, and investments are posited as antecedents of relationship commitment. Commitment, in turn, is a significant predictor of relationship breakup, accounting for over half of the variance in this key outcome (Le, Dove, Agnew, Korn, & Mutso, 2010; Le & Agnew, 2003).

The robustness of the investment model has been demonstrated in dozens of empirical studies and via meta-analysis (Le & Agnew, 2003; Rusbult et al., 2012). The model has been shown to predict relationship continuance over time and a host of relationship maintenance behaviors (Agnew & VanderDrift, 2015). The model has been employed in a range of studies applying the model to participants of diverse ethnicities (e.g., Davis & Strube, 1993), homosexual and heterosexual partnerships (e.g., Kurdek, 1995), and abusive relationships (e.g., Choice & Lamke, 1999), with moderator analyses suggesting that the associations between commitment and its theorized determinants vary minimally as a function of demographic (e.g., ethnicity) or relational (e.g., duration) factors (Le & Agnew, 2003).

Relationship Commitment and HIV/STI Risk

Beyond maintenance and persistence, commitment has also been shown to be associated with condom use, with stronger commitment associated with lower condom use in casual relationships (VanderDrift, Lehmiller, & Kelly, 2012) and with condom use less likely within ongoing relationships than within casual partnerships (Anderson, 2003; Misovich, Fisher, & Fisher, 1997). Rather than being more careful in sexual relations with a known partner (motivated, one might reason, by increased affection for that partner), the available evidence suggests the opposite: one’s defenses seem to drop and trust appears to increase (Simpson, 2007; Wieselquist, Rusbult, Foster, & Agnew, 1999).

The consequences of strong commitment identified from past work using the investment model suggest the commitment-perceived vulnerability linkage displayed in Figure 1. Past research suggests that individuals often ignore self-interest and willingly put themselves at potential risk within the context of a committed relationship (Buunk & Bakker, 1997; Pilkington & Richardson, 1988). Agnew and Dove (2011) directly tested the association between commitment and perceived vulnerability to harm from a partner, finding significant negative associations between commitment level and partner-based personal harm perceptions, and that greater commitment leads to (a) decreased perceptions of a partner as a source of risk to the self, and (b) increased risky behaviors by the self. Thus, past findings are consistent with the notion that relationship commitment inspires a departure from self-interest and a positive skewing of partner-oriented perceptions (Murray et al., 2013). Accordingly, as commitment increases, decreased perceived vulnerability from one’s partner may lead to decreased condom use intentions (Sheeran, Abraham, & Orbell, 1999), with intentions shown to be significantly associated with condom use in prior research (Albarracin, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Sheeran & Orbell, 1998).

Method

In order to examine the hypothesized associations outlined above, we conducted a longitudinal study of individuals at elevated risk for HIV/STI acquisition, with four distinct measurement occasions at four-month intervals over one year. All data collection periods involved individual men and women who met study inclusion criteria: 1) 18 to 30 years old; 2) engaged in condomless vaginal or anal sex within the past three months; and 3) reported at least one of the following: (a) more than one sexual partner in the past year; (b) treatment for an STI during the past 2 years; (c) ever used injection drugs; (d) for women only, ever had sex with a man who had sex with men; (e) ever had sex with someone who used injection drugs; (f) ever had sex with someone who was HIV-positive; (g) had sex during the past year with someone who had an STI; (h) had or have a partner who has had sex with someone else during the past year; and (i) had or have a partner who they suspected or suspect may have sex with someone else in the next year while they were or are still together. We selected these criteria because they identified individuals who were currently at increased risk of HIV/STIs, those whose prior behavior put them at increased risk, and those who may be at increased risk in the future.

Participants and Data Collection

Participants were recruited as part of [study name blinded for review]. [Study name blinded for review] is a longitudinal study that examined relationship dynamics within the heterosexual involvements of men and women of reproductive age at increased risk for HIV infection. Participants were recruited between 2006 and 2008 from clinics and community locations in East Los Angeles, California.

In-person computer-assisted interviews of approximately one hour were administered using the Questionnaire Development System (QDS) software program. Participants were matched with interviewers by gender and, in most cases, by race or ethnicity. Participants were offered the option of being interviewed in Spanish; however, all participants chose to be interviewed in English. For sensitive questions, participants were given the option of entering their answers directly into the computer. Over the course of one year, participants (N = 538 at Time 1; 276 female, 261 male, 1 did not report) completed four in-person interviews at 4-month intervals (Time 1-Time 4). At Time 2, Time 3 and Time 4, a total of 436, 377, and 330 individuals were interviewed, respectively, for a retention rate from Time 1 of 81%, 70% and 62% (attrition rate did not differ significantly by participant gender or race). Participants were compensated $30, $35, $40, and $45 for the Time 1 through Time 4 interviews, respectively. Transportation and childcare costs were reimbursed up to $20 at each interview. The Institutional Review Board at Oregon State University had primary ethical oversight and approved the study protocol and materials.1

During each interview, participants provided data regarding all sexual relationships (identified by initials or nickname) they had had in the previous four months (total across time periods = 1262). Nicknames or initials were used to link data about partners across interviews; this procedure allowed us to track changes in an individual’s partnerships over time. The study included data from 710 unique relationships, including 501 that were ongoing at Time 1 and 209 that began between Time 1 and Time 4. At Time 4, 200 relationships were ongoing, whereas 510 had ended at some point prior to Time 4.

The majority of participants were in their early- to mid-twenties at Time 1 (age M = 23.98, SD = 5.12, Median = 23), and with regard to racial/ethnic composition, the sample was composed of roughly equivalent numbers of participants who identified as White, Black, and Hispanic (30.5%, 26.6%, and 23.9%, respectively, with 12.8% multi-racial and 6.2% other). Their relationships at Time 1 were primarily described as exclusive dating relationships (57.8%, with 10.2% dating causally, 5.3% just friends, 12.4% engaged to be married, 9.8% married, and 4.5% other). The average duration of their sexual relationships was 23.3 months at Time 1 (SD = 24.8, Median = 14). Over the course of the four waves of the study, new partnerships were added to the data as participants reported them, so the study relationship duration average was lower than the Time 1 average (M = 11.3 months). Over the course of the study, participants reported on average 18.3 sexual acts between waves with each partner (e.g., between Time 1 and Time 2, or between Time 3 and Time 4), of which 46.3% of them were reported as sex with condoms (SD = 43%). Over one-quarter of the participants reported perfect condom use with a particular partner between waves (28.9%), whereas 33.5% reported never using a condom with a particular partner between waves.

Measures

Investment Model constructs for each sexual partnership

Participants completed the Investment Model Scale with respect to each of their on-going sexual partners at each of the 4 time periods. This 22-item validated measure (Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998) contains four subscales that assess each component of the Investment Model, including commitment level [7 items; e.g., “I want our relationship to last forever;” 9-point Likert-type response scale, with 0 = Do Not Agree at All and 8 = Agree Completely; α = .94 (Time 1), .93 (Time 2), .94 (Time 3), .94 (Time 4)] and its three theorized determinants: satisfaction level [5 items; e.g., “I feel satisfied with our relationship”; α = .92 (Time 1), .91 (Time 2), .94 (Time 3), .94 (Time 4)], quality of alternatives [5 items, e.g., “The people other than my partner with whom I might become involved are very appealing”; α = .79 (Time 1), .64 (Time 2), .81 (Time 3), .68 (Time 4)], and investment size [5 items; e.g., “Compared to other people I know, I have invested a great deal in my relationship with my partner”; α = .88 (Time 1), .87 (Time 2), .86 (Time 3), .89 (Time 4)]. These items were adapted to be partner-specific based on partner information provide by participants (e.g., in assessing commitment level: “I want my relationship with [PARTNER A’S INITIALS/NICKNAME] to last forever”).

Perceived invulnerability to harm from each partner

We administered six items to assess individual’s perceptions of HIV/STI risk from each of their on-going sexual partners (e.g., “How likely is it that you could get HIV from having sex with [PARTNER A] without using a condom?”), adapting questions from existing perceived vulnerability inventories including measures developed by Reisen and Poppen (1999). Reliability for this scale was high (α = .93 at Time 1, .94 at Time 2, .93 at Time 3, and .93 at Time 4)

Intentions to use condoms with each partner

To measure condom use intentions, we employed a four-item measure used in past research and adjusted for the timeframe of [study name blinded for review] (Agnew, 1999; e.g., “I intend to use a condom during sexual intercourse over the next four months with [PARTNER A],” and “I will make an effort to use a condom during sexual intercourse over the next four months with [PARTNER A]).” These items were each rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“definitely not”) to 5 (“definitely”), so high values on this scale indicated high intention to use condoms (α = .94 at Time 1, .93 at Time 2, .94 at Time 3, and .94 at Time 4).

Condom use with each partner

At each time period, we assessed condom use over the previous 4 months by asking participants to report for each partner the number of times they had sex (vaginal and anal) in the previous four months and the number of times a condom was used. To measure condom use, we coded their responses as a ratio of acts of intercourse with a condom to total acts of intercourse, ranging from 0 – 1. Similar measures of condom use have been commonly used in HIV prevention research with gay/bisexual men (e.g., Kelly, St. Lawrence, & Brasfield, 1991), inner-city heterosexual women (e.g., Carey, Maisto, Kalichman, Forsyth, Wright, & Johnson, 1997), and inner-city heterosexual men (e.g., Kalichman, Rompa, & Coley 1997).

Demographic variables

Finally, participants answered demographic questions about themselves, their partner(s), and their relationship, including questions about age, gender, race/ethnicity, and relationship duration (see “Participants” section for measures of central tendency).

Results

Data preparation and treatment of missing values is described in detail in Footnote 2. For all analyses, we used Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) to handle missing data. To be conservative, we additionally reran all analyses presented subsequently using multiple imputation (N = 20 imputations) to project results. The results from these analyses are consistent with what we present below (i.e., the model fit, path coefficients, and effect sizes do not change substantively).

To test the overall model presented in Figure 1, we constructed a three-level model in Mplus version 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 2015). Because condom use was found to be non-normally distributed, we estimated our model using Maximum Likelihood Estimation with Robust Standard Errors (MLR). In this model, time points were nested within partners, which were nested within participants. In total, we had data from 487 participants, who reported on 710 relationships (M = 2.36), and the average number of time points that they reported on each relationship was 1.62. For our main model testing, we controlled for gender, race, and relationship duration (at the first reporting of the relationship), by including them as predictors of each endogenous variable (i.e., commitment, perceived vulnerability, condom use intentions, and condom use). As hypothesized, when considered simultaneously, each of the paths was significantly different from zero (see Figure 1). Overall, the model fit the data marginally well (RMSEA = .08, CFI = .88, SRMR = .09). Removing the covariates, all paths remained significant and overall model fit remained consistent (RMSEA = .08, CFI = .89, SRMR = .10).

We also computed a number of alternative models to the one suggested in Figure 1. For example, we analyzed a model that allowed each of the theorized bases of commitment to directly predict perceived vulnerability (bypassing commitment). The fit of this model did not improve upon overall fit (RMSEA = .14, CFI = .28, SRMR = .25). We also computed a model in which commitment directly predicted intentions and a model in which commitment directly predicted condom use; neither of these models resulted in improved fit (commitment-intentions: RMSEA = .07, CFI = .80, SRMR = .17; commitment-condom use: RMSEA = .08, CFI = .76, SRMR = .21). Finally, we ran our hypothesized model separately for male participants and female participants. Overall fit was comparable for both, and similar to the overall model fit presented above (men: RMSEA = .08, CFI = .90, SRMR = .07; women: RMSEA = .09, CFI = .86, SRMR = .12)

Discussion

Condoms are currently the only widely available method of STI prevention and the only method for protecting against both HIV/STI and unintended pregnancy for sexually active individuals. Understanding the complex factors that influence condom use is critical, therefore, to understanding HIV/STI and pregnancy risk and prevention in young adults. Despite the relational reality of sexual and HIV prevention behaviors, few studies have considered the role of the relational context in decision-making for protective behavior, including condom use. In addition, most theories that have been applied to understanding the determinants of condom use have focused heavily on individual-level constructs and not on relational qualities.

Guided by the investment model of commitment processes adapted for understanding condom use, the current study addresses these gaps in the literature and extends previous research by examining relationship qualities within specific partnerships to increase understanding of condom use. Overall, our findings provide support for the associations proposed in the theoretical model presented in Figure 1. Specifically, we found that satisfaction with and investment in a relationship were positively associated with commitment whereas quality of alternatives was negatively so. These findings are consistent with a meta-analysis of the investment model (Le & Agnew, 2003), which found that across 52 studies, including 60 independent samples, satisfaction with, alternatives to, and investment in a relationship each correlated significantly with commitment to that relationship.

As predicted, we also found that higher levels of commitment were associated with lower perceived vulnerability to harm from one’s partner that, in turn, was associated with decreased condom use intentions and decreased condom use. The current findings add to a body of research that has shown condom use is inversely associated with relational measures that characterize the relationship as long-lasting, durable, stable, and/or exclusive (Manning et al., 2012; Ku, Sonesnstein, and Pleck, 1994). Unfortunately, the cognitive consequences of relationship commitment may leave an individual susceptible to potential health risks, including HIV/STI acquisition. From a safer sex promotion viewpoint, the commitment-perceived vulnerability linkage is particularly worrisome. Moreover, as individuals often fear that suggesting the potential for HIV/STI risk within their relationship could pose a threat to the relationship itself (Bowen & Michal-Johnson, 1989; Wingood, Hunter-Gamble, & DiClemente, 1993), greater commitment may inhibit discussion necessary for couple members to ascertain critical objective indicators of own risk.

The current study suggests that commitment plays an important role in STI prevention; however, that role may be seen as conflicting in light of the broader literature. Whereas the current results revealed that commitment is negatively associated with condom use, other work has shown that it is positively associated with maintaining a monogamous relationship and not engaging in sexual concurrency (Warren, Harvey, & Agnew, 2012). Commitment level should, therefore, be considered in contraceptive counseling and interventions to prevent transmission of STIs. Although interventions may be designed to encourage couples to build intimacy and commitment, they also need to emphasize the need for HIV/STI testing, improvement in communication with one’s partner, including the discussion of monogamy agreements, and increased awareness about sexual risk before the discontinuation of condom use (Warren, Harvey, & Agnew, 2012). Great strides have been made in couple-based behavioral interventions (e.g., El-Bassel & Wechsberg, 2012; El-Bassel et al., 2003; Jiwatram-Negro´n & El-Bassel, 2014) and the current findings highlight the continued need to take relational elements into account in ultimately reducing HIV risk within sexual partnerships.

It is important to note that several couple-based interventions focused on the prevention of HIV risk behavior have been implemented and evaluated. Burton and colleagues (2010) conducted a systematic review of studies (e.g., Harvey et al., 2009; El Bassel et al., 2003) examining whether couple-focused behavioral prevention interventions reduced risk behavior. The authors found that these interventions consistently reduced condomless intercourse and improved condom use among participants compared to controls. Despite much progress on these prevention efforts, couple-based interventions remain limited with numerous methodological gaps (see El-Bassel & Wechsberg, 2012; Jiwatram-Negro´n & El-Bassel, 2014). For example, because most couple-based studies use stringent criteria for their definition of a couple which likely results in a sample of more stable couples, the dyad sample may be limited by selection bias (El-Bassel & Wechsberg, 2012). Because the current sample consists of individual men and women, not dyads, our findings contribute to a better understanding of how the relational context impacts individuals who are in relationships, along a continuum from relative strangers to long-term partners. Importantly, the dyadic perspective does not necessary require an ongoing relationship between two individuals. As Karney and colleagues aptly note (2010, page 190), “although all relationships are dyads, not all dyads are relationships.” Taken together, these findings suggest the importance of implementing interventions targeted at couples as well as interventions that focus on the relationship context targeted at individuals.

Notable strengths of the current study lie in the use of a novel prospective methodological approach for measuring and modeling the dynamics and qualities of sexual relationships over time. The study is theoretically grounded in a well-developed conceptual model of factors underlying decisions to stay with (or leave) a given sexual partner, with ongoing dynamic relational qualities at its core. Data to assess the relational context were collected using relationship measures that were partner-specific. These measures were assessed for all sexual partnerships, including concurrent relationships, for each individual on multiple occasions over the course of one year. Furthermore, by using a sample comprised of roughly equal numbers of White, Black, and Hispanic participants, we feel more confident regarding the generalizability of the findings across racial and ethnic groups. Finally, both men and women at increased risk for HIV were included in the study. A significant gap in knowledge concerns HIV risk among men who have sex with women and men’s perception of power in sexual partnerships (Blanc, 2001; Amaro & Raj, 2000).

This study is not without limitations. For example, overall model fit could be better. Past work highlighting the importance of dyadic condom use intentions (i.e., collecting the measure of condom use from both partners) provides insight as to what might be a better approach to assess both intentions and behavior (VanderDrift, Agnew, Harvey, & Warren, 2013), and suggests that model fit would improve upon the addition of the other actor’s intentions. Because the current sample was obtained in a large metropolitan area within the United States, our results may not be generalizable to young adults who engage in risky sexual behavior from other areas. Because of attrition over the 4 periods of data collection, it is possible that the most at-risk participants were lost to follow-up. In a separate attrition analysis, however, we found that the reasons for condom use were not meaningfully associated with loss at follow up. Finally, when collecting data on sexual intercourse, we did not distinguish between vaginal and anal sex. Because many previous studies had reported low numbers of anal sex reported by participants in similar samples, we asked about vaginal and anal intercourse together.

In addition, to test our model we could only include relationships that were ongoing at any of the first three assessment periods (due to known problems with respect to retrospective memory biases in reports of relationship quality in relationships that have ended; McFarland & Ross, 1987), and also featured data with respect to condom use in that relationship at a later assessment. Thus, the current study did not capture reports of particularly brief relationships (i.e., relationships that both began and ended between study assessments) and is limited with respect to understanding the model’s applicability to relationships less than four months in duration. Moreover, the lagged analyses involving condom use, although suggestive of a causal association with earlier model variables, does not provide definitive evidence of causality. The utility of using a lagged variable to approximate causal inference depends on a number of factors, including potential feedback between condom use and other model variables and potential third-variable confounders (Robins, Hernán, & Brumback, 2000).

These findings have significant implications for the design of interventions for reducing the risk of HIV infection among individuals in close relationships. The better we can understand the association between the characteristics and dynamics of sexual partnerships and risky behavior, the better we will be able to address the multiple barriers to safer sex behavior that occur within heterosexual relationships. The current findings suggest that feelings of commitment to a sexual partner are associated with a reduction in sense of risk. Thus, the current findings contribute to the design of interventions that focus on changing sexual risk behavior within individuals involved in sexual relationships, including suggesting the importance of raising awareness of relational qualities that may give rise to unsafe sexual practices.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD47151 to S. Marie Harvey (PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The POPD protocol and study materials were also reviewed and approved by IRBs at California State University at Los Angeles and at Purdue University.

In preparing the data for analyses, we lagged the condom use ratio by one time-point in order to place it within the same data row as the hypothesized predictors of it. For example, during her Time 2 session, a participant completed measures of all of the predictors with regard to a given relationship (e.g., satisfaction, condom use intentions). When she returned at Time 3, she completed measures assessing how many sexual acts she engaged in with that particular relationship partner, as well as how many of those acts included use of a condom. To analyze these data, we lagged her Time 3 report of condom use so that it was on the same row of data as her Time 2 reports of the predictors. Thus, her row of data for Time 2 now includes measures of all of the predictors of condom use (i.e., satisfaction, alternatives, investment, commitment, perceived vulnerability, and condom use intentions) as well as the ratio of acts of intercourse with a condom over the next four months. This allowed for the elimination of time as a predictor from all subsequent models. Following data preparation, we examined patterns of missingness to determine the most appropriate analyses. To start, we created a stacked dataset in which each time point had a row within each relationship within each participant (time points were nested within relationships within participants). We followed every relationship reported, even after it dissolved, so every partnership has a row for every time point beginning the first time it was reported. For example, a participant who reported three partnerships at Time 1, then added one partnership each at Times 2, 3, and 4 would have 18 rows of data: each Time 1 partner has four rows (Times 1–4), the partnership added at Time 2 has three rows (Times 2–4), the partnership added at Time 3 has two rows (Times 3 and 4), and the partnership added at Time 4 has one row (Time 4). In total, we had 3051 rows of data. Of these, we used listwise deletion to eliminate 1594 rows in which the relationship was not ongoing (i.e., it had dissolved at a previous time point or during the four months preceding that time), and 307 rows in which the predictors of interest were measured at Time 4 (because we would not be able to assess condom use for that partnership over the subsequent 4 months, as it was then beyond the range of the study). Of the remaining 1150 rows of data, we observed three patterns of missingness: 1) full data to test the theorized model, with data from two sequential time point (n = 794), 2) participant attrition before condom use was reported (n = 309), and 3) participants failed to complete one or more measures (n = 47). Thus, we end with a missing data rate of about 31%.

Contributor Information

Christopher R. Agnew, Purdue University

S. Marie Harvey, Oregon State University.

Laura E. VanderDrift, Syracuse University

Jocelyn Warren, Lane County Health and Human Services.

References

- Agnew CR. Power over interdependent behavior within the dyad: Who decides what a couple does? In: Severy LJ, Miller WB, editors. Advances in population: Psychosocial perspectives. Vol. 3. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1999. pp. 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew CR. Commitment, theories and typologies. In: Reis HT, Sprecher SK, editors. Encyclopedia of human relationships. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew CR, Dove N. Relationship commitment and perceptions of harm to self. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2011;33:322–332. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew CR, VanderDrift LE. Relationship maintenance and dissolution. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, editors. APA handbook of personality and social psychology. Vol. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. pp. 581–604. (Interpersonal relations). [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:142–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: Power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42:723–749. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JE. Condom use and HIV risk among US adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:912–914. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Agnew CR. Being committed: Affective, cognitive, and conative components of relationship commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1190–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Becker MH. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: An examination of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32:189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SP, Michal-Johnson P. The crisis of communicating in relationships: Confronting the threat of AIDS. AIDS and Public Policy Journal. 1989;4:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Burton J, Darbes LA, Operario D. Couples-focused behavioral interventions for prevention of HIV: Systematic review of the state of evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Bakker AB. Commitment to the relationship, extra dyadic sex, and AIDS preventive behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:1241–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson B. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Towards an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS risk reduction model (ARRM) Health Education Quarterly. 1992;17:53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence among adults and adolescents in the United States, 2007-2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2014 [On-line] 2014 Available: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/default.htm.

- Choice P, Lamke L. Stay/leave decision-making in abusive dating relationships. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Strube MJ. An assessment of romantic commitment among black and white dating couples. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1993;23:212–225. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Hill J, Steinglass P. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:963–969. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Wechsberg WM. Couple-based behavioral HIV interventions: Placing HIV risk-reduction responsibility and agency on the female and male dyad. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice. 2012;1:94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SM, Kraft JM, West SJ, Taylor AB, Pappas-DeLuca KA, Beckman LJ. Effects of a health behavior change model-based HIV/STI prevention intervention on condom use among heterosexual couples: A randomized trial. Health Education and Behavior. 2009;36:878–94. doi: 10.1177/1090198108322821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiwatram-Negro´n T, El-Bassel N. Systematic review of couple-based HIV intervention and prevention studies: Advantages, gaps, and future directions. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18:1864–1887. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0827-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Lack of positive outcomes from a cognitive-behavioral HIV and AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city men: Lessons from a controlled pilot study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1997;9:299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, Reis HT, Rothman AJ, Simpson JA. A framework for incorporating dyads in models of HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9802-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BP, Fortenberry D, Zimet GD, Blythe MJ, Orr DP. Partner-specific relationship characteristics and condom use among young people with sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Brasfield TL. Predictors of vulnerability to AIDS risk behavior relapse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:163–166. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. The dynamics of young men’s condom use during and across relationships. Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;26:246–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Assessing multiple determinants of relationship commitment in cohabiting gay, cohabiting lesbian, dating heterosexual, and married heterosexual couples. Family Relations. 1995;44:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Le B, Agnew CR. Commitment and its theorized determinants: A meta-analysis of the Investment Model. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Le B, Dove NL, Agnew CR, Korn MS, Mutso AA. Predicting non-marital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Welti K, Barry M, Peterson K, Schelar E, Wildsmith E. Relationship characteristics and contraceptive use among young adults. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;43:119–128. doi: 10.1363/4311911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Flanigan CM. Young adult dating relationships and the management of sexual risk. Population Research and Policy Review. 2012;31:165–185. doi: 10.1007/s11113-011-9226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantell JE, DiVittis AT, Auerback MI. Evaluating HIV prevention interventions. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland C, Ross M. The relation between current impressions and memories of self and dating partners. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1987;13:228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Misovich SJ, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:72–107. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Gomillion S, Holmes JG, Harris B, Lamarche V. The dynamics of relationship-promotion: Controlling the automatic inclination to trust. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:305–334. doi: 10.1037/a0030513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington CJ, Richardson DR. Perceptions of risk in intimacy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1988;5:503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach: Crossing the traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Amaro H. Culturally tailoring HIV/AIDS prevention programs: Why, when, and how. In: Kazarian SS, Evans DR, editors. Handbook of cultural health psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 195–239. [Google Scholar]

- Reisen CA, Poppen PJ. Partner-specific risk perception: A new conceptualization of perceived vulnerability to STDs. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29:667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Robins J, Hernán M, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg RB, Wasserheit JN, St Louis ME, Douglas JM, the Ad Hoc STD/HIV Transmission Group The effect of treating sexually transmitted diseases on the transmission of HIV in dually infected persons: A clinic-based estimate. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2000;27:411–416. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Agnew CR, Arriaga XB. The Investment Model of Commitment Processes. In: Van Lange PAM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology. Vol. 2. Los Angeles: Sage; 2012. pp. 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CA. The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships. 1998;5:357–391. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton J, Garnett G, Rottingen JA. Metaanalysis and metaregression in interpreting study variability in the impact of sexually transmitted diseases on susceptibility to HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32:351–357. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154504.54686.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:90–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Orbell S. Do intentions predict condom use: Meta-analysis and examination of six moderator variables. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;37:231–250. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1998.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA. Psychological foundations of trust. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:264–268. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman AR, Clark MR, Doncel GF. Multipurpose prevention technologies: Biomedical tools to prevent HIV-1, HSV-2, and unintended pregnancies. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;2011:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2011/429403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderDrift LE, Agnew CR, Harvey SM, Warren J. Whose intentions predict? Power over condom use within heterosexual dyads. Health Psychology. 2013;32:1038–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0030021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderDrift LE, Lehmiller JJ, Kelly JR. Commitment in friends with benefits relationships: Implications for relational change and safer sex practices. Personal Relationships. 2012;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JT, Harvey SM, Agnew CR. One love: Explicit monogamy agreements among heterosexual young adult couples at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49:282–289. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.541952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieselquist J, Rusbult CE, Foster CA, Agnew CR. Commitment, pro-relationship behavior, and trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:942–966. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Hunter-Gamble D, DiClemente RJ. A pilot study of sexual communication and negotiation among young African American women: Implications for HIV prevention. Journal of Black Psychology. 1993;19:190–203. [Google Scholar]