Abstract

Purpose

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to evaluate and compare the prevalence of congenital anomalies in babies and fetuses conceived after four procedures of assisted reproduction technologies (ART).

Methods

The prevalence of congenital anomalies was compared retrospectively between 2750 babies and fetuses conceived between 2001 and 2014 in vitro fertilization with standard insemination (IVF), IVF with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), IVF with frozen embryo transfer (FET-IVF), and ICSI with frozen embryo transfer (FET-ICSI). Congenital anomalies were described according to European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) classification. The parental backgrounds, biologic parameters, obstetric parameters, and perinatal outcomes were compared between babies and fetuses with and without congenital anomalies. Data were analyzed by the generalized estimating equation.

Results

Between 2001 and 2014, a total of 2477 evolutionary pregnancies were notified. Among these pregnancies, 2379 were included in the analysis. One hundred thirty-four babies and fetuses had a congenital anomaly (4.9%). The major prevalences found among the recorded anomalies were congenital heart defects, chromosomal anomalies, and urinary defects. However, the risk of congenital anomalies in babies and fetuses conceived after FET was not increased compared with babies and fetuses conceived after fresh embryo transfer, even when adjusted for confounding factors (p = 0.40).

Conclusions

There is no increased risk of congenital anomalies in babies and fetuses conceived by fresh versus frozen embryo transfer after in vitro fertilization with and without micromanipulation. Indeed, distribution of congenital anomalies found in our population is consistent with the high prevalence of congenital heart defects, chromosomal anomalies, and urinary defects that have been found by other authors in children conceived by infertile couples when compared to children conceived spontaneously.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-017-0903-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Congenital anomalies, Perinatal outcomes, In vitro fertilization, Intra cytoplasmic sperm injection, Frozen embryo transfer

Introduction

Assisted reproduction technologies (ART) have been used increasingly worldwide since the birth of the first child conceived by in vitro fertilization with standard insemination (IVF) in 1978 [1]. This is a consequence of environment and social behavior changes and rising demand for male and female infertility treatment.

The introduction of the in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in 1992 allowing the treatment of male infertility [2] and the substantial development of cryobiology have considerably contributed to ART efficiency improvement. A recent meta-analysis showed that the use of frozen embryo transfer (FET) significantly improved clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates [3]. Due to these late major evolutions in technical procedures, it remains essential to evaluate the safety of our practice regarding maternal outcomes and children health.

The evaluation of children health is a complex task due to the coexistence of multiple confounding factors such as technique procedure used to treat infertility, parental background [4, 5], and the necessity to perform studies over a long-term period to measure the risk variation.

Congenital anomalies are one of the main criteria used for assessing the safety of the procedure and children health. Their prevalence in European general population is estimated to be 2.4% between 1998 and 2012 according to the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) Register [6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines them as structural or functional anomalies that occur during intrauterine life and can be identified prenatally, at birth or later in life. The EUROCAT oversees epidemiological surveillance of such anomalies by collecting data on major structural defects caused by abnormal morphogenesis (congenital malformations, deformation, disruptions, and dysplasia), chromosomal abnormalities, inborn errors of metabolism, and hereditary diseases [7].

Several independent studies have already described increased risks of congenital anomalies in children born after the ART [8–13]. A systematic review and a meta-analysis [14] of 45 studies allowed evaluating the risk of congenital anomalies in children born after ART versus non-ART children. When pooling the data of 45 studies, results indicated a significant 30% increased the risk of birth defects in children born after ART (risk ratio [RR] 1.32, 95% CI 1.24–1.42). This risk increased when they studied only major birth defects and the singletons (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.30–1.43) [14]. Besides, a meta-analysis of 24 studies comparing children conceived by IVF and those born after ICSI failed to identify an increase in the risk of congenital anomalies in ICSI children compared with IVF (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.91–1.20) [15]. Several studies have evaluated the health of children born after FET [16–20]. The latest publications suggested that these children have better perinatal outcomes compared with children born after fresh embryo transfer [21, 22] but have an increased risk of being born large for gestational age (LGA) [23]. The prevalence of congenital anomalies was not different in these children against prevalence in children born after fresh embryo transfer (odds ratio [OR] 0.95, 95% CI 0.71–1.27) [24].

Although the surveillance of ART procedure outcome (excluding the follow-up of children health) in France was established in 1986 by a national register for IVF [25, 26], the health of children born after ART has been addressed only by few authors in France [27–31]. In 2013, the rate of children born after ART in France was estimated to 2.9% [32]. Sagot and colleagues estimated that among French singletons born after in vitro fertilization technologies (IVF, ICSI, and FET), the congenital anomaly prevalence was 4.2%. They showed an increased prevalence of major congenital malformations in these singletons than in an unexposed group (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.3–3.1) [30].

As too few data on children born after ART procedure in France were available, we have launched a long-term follow-up of IVF and ICSI children in 2003 based on the collection of data concerning a historical cohort that started in 1994, at the opening of the center [33–35]. The present study was conducted to provide further data to feed the existing debate on the health of children conceived by ART procedures. The aim of the present study was double. Firstly, to assess and to compare the prevalence of congenital anomalies in babies and fetuses conceived with four distinct ART procedures: (i) the transfer of fresh embryo obtained after IVF (IVF), (ii) the transfer of fresh embryo obtained after (ICSI), (iii) the transfer of frozen embryo obtained after IVF (FET-IVF), and (iv) the transfer of frozen embryo obtained after ICSI (FET-ICSI). Secondly, we compared biologic, obstetric, and perinatal characteristics between fetuses/babies with and without congenital anomalies.

Material and methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective analysis of fetuses and babies conceived after ART procedures from a historical cohort of a French center (donor excluded). This research focused on congenital anomalies in four groups of infertility treatment: IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI. These four groups were chosen because they correspond to the four techniques the most used in our center. ART are strictly regulated in France [36]. Data used to conduct the present study were obtained in accordance with French Bioethics Law that controls the collection of data related to ART programs and children follow-up. No further data outside the legal framework were requested to the couples.

ART procedures

Ovarian stimulation was performed with conventional protocols based on pituitary control with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist or antagonist; administration of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) urinary (u-FSH) or recombinant (r-FSH) was used to induce ovulation. In the IVF, oocyte-cumuli complexes were inseminated with motile spermatozoa. In the case of ICSI, oocyte denudation was performed after oocyte retrieval. Subsequently to denudation, oocytes were incubated in a BM1 medium before ICSI. The embryo culture conditions and embryo transfer policy have considerably changed since the opening of the laboratory in 1994. Basically, before 2003, embryos obtained after IVF and ICSI were cultured from day 1 (D1) to day 2/day 3 (D2/D3) in the same BM1 medium. Subsequently, day 4 to day 5 (D5) embryos were cultured under other conditions. From 2003 to present, D1 to D5 embryos obtained after from IVF and ICSI are cultured under the same single-step global medium conditions. Since 2004, no more than two embryos were proposed for transfer whatever the clinical situation including maternal age. Although D5 embryo transfer was privileged, depending on embryo quality, transfer on D2/D3 is still punctually proposed to the couple. Poor-quality embryos were discarded [37]. For slow freezing, after successive incubations at room temperature in solutions containing propanol, embryos were loaded in polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG) clear rigid embryo straw and were subsequently subjected to slow freezing in a programmable freezer. A maximum of two frozen/thawed embryos were transferred in the spontaneous ovarian cycle (in normal ovulatory women) or using substitute hormonal treatment (in other cases) for endometrium preparation. Since 2013, embryo cryopreservation is performed using dimethyl sulfoxide with ethylene glycol (DMSO/EG) exposure before vitrification. Embryos were not genetically tested prior to transfer.

Pregnancies were assessed by blood human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) detection (>100 UI/L) followed by ultrasound assessment of fetal heartbeat. Data concerning pregnancies from the beginning to the delivery were collected in a software dedicated to the follow-up of couples involved in an ART program (Médifirst® database).

Data collection

Background characteristics

The details of treatment with ART were provided by the medical folder, used in the center for recording medical, clinical, and biological data of couples. The parental backgrounds and biologic parameters were filled in using this medical folder. The obstetric parameters were provided by the maternity hospitalization report.

The background characteristics of biologic and obstetric results comprise the following:

Parental backgrounds: maternal and paternal age at conception (years), maternal and paternal body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), maternal smoking behavior, antecedents (preexisting diabetes and women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES daughter), and parity

Biologic parameters: the day of embryo transfer (D2/D3 or D5) and the number of embryos transferred

Obstetric parameters: pregnancy complications (placenta previa, high blood pressure induced by pregnancy and gestational diabetes), cesarean section, and the twin pregnancy)

Perinatal outcomes

Data compiled for medical termination of pregnancy (MTP) and deliveries were collected from maternity hospitalization report or a copy of the personal child health record document. The information about the perinatal outcomes and congenital anomalies in the neonatal period provided by the auto-questionnaire filled by parents were verified and validated by a medical report. When this information could not be verified, the babies and fetuses were excluded from the analysis. Perinatal outcomes were preterm birth (PTB) defined by delivery with less 37 weeks gestational age (WGA), low birth weight (LBW) defined by less of 2500 g, gender, and the congenital anomalies.

Congenital anomalies

This study concerns only the congenital anomalies detected at birth or in the neonatal period (within 28 days after birth). The follow-up of these defects was not studied in the present article. The congenital anomalies were coded by a medical doctor using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10). Only major congenital anomalies were classified according to the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) guidelines in 13 classes: nervous system; eyes; ears, face, and neck; congenital heart defects; respiratory; oro-facial clefts; digestive system; abdominal wall defects; urinary; genital; limb; and other anomalies/syndromes and chromosomal. According to EUROCAT guide, revised in October 2010, the following cases were not registered: (1) cases of cerebral palsy and (2) cases with only minor defects, excluding when those anomalies were associated with major anomalies.

A child displaying several different malformations was counted in more than one class of malformation, except when a child showed a syndrome (the anomalies associated with the syndrome were not counted separately).

Population

The full cohort included 3165 clinical pregnancies from 1994 to 2014. We have restricted the analysis to babies and fetuses conceived between 2001 and 2014 where the data reliability rate was over 90% (Supplementary Fig. 1).

This study comprised the MTP and the deliveries (live births, stillbirths after 22 WGA) from IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI procedures between 2001 and 2014. The evolution of pregnancies and neonatal data was collected prospectively, except for babies born before 2004. Neonatal data of these babies were collected retrospectively [34].

The following situations were not included in the study: (a) triplet babies (n = 12), because we did not have enough children, and their background characteristics could bias the results; (b) babies born after vitrified/warmed embryos (n = 76), because this procedure was introduced in 2012 and it is too early to draw any conclusion on the technical changes of the freezing.

Statistical analysis

All variables were described by proportions N (%) and mean (±standard deviation [±SD]). We then compared the four groups of procedures (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI) among background characteristics and perinatal outcomes. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) for correlated data to compare the four groups of procedures (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI) among background characteristics and perinatal outcomes. The GEE allowed taking into account the correlation between subjects due to multiple pregnancies and siblings (same mother). To analyze if procedures have an impact on the risk of congenital anomalies, we performed an etiological analysis, modeling the congenital anomalies depending on risk factors including the group of procedures. Firstly, we compared and described the two groups (babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies versus babies and fetuses without congenital anomalies). Secondly, we performed a multivariate GEE to adjust for confounding factors. All variables with a p value <0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate GEE (maternal smoking behavior, parity, high blood pressure induced by pregnancy and twins). Using a backward selection method, we finally retained one variable, namely twins, in the final adjusted model. The groups (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI) were systematically added into the multivariate analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 17 (SPSS, IBM Corporation, USA). A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Inclusion

Between 2001 and 2014, a total of 9685 oocytes retrievals were performed in our center. Of embryo transfers (fresh and frozen embryos), 11,530 were achieved. The pregnancy rate after embryo transfer during this period was 27% with a miscarriage rate of 18%.

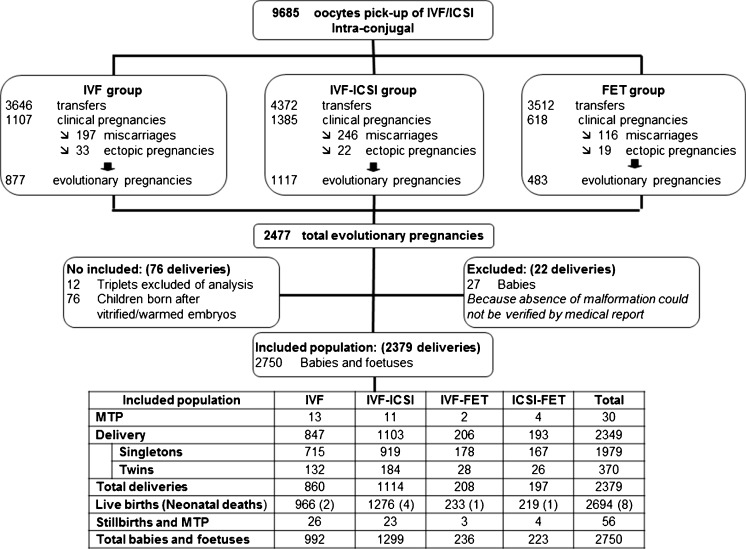

A total of 2349 deliveries were included in the analysis; 847 occurred after IVF, 1103 after ICSI, 206 after FET-IVF, and 193 after FET-ICSI treatment. Thirty MTP were reported. Among these deliveries, 2750 children were born (2694 live births and 56 stillbirths/fetuses or MTP); eight neonatal deaths were reported (two after IVF, four after ICSI, one after FET-IVF, and one after FET-ICSI) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the activity of the center between 2001 and 2014 and the description of the population included in the analysis. MTP medical termination of pregnancy, IVF in vitro fertilization with standard insemination, ICSI in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection, FET frozen embryo transfer

Characteristics according to ART procedures

The description and comparison of background characteristics and perinatal outcomes between the four procedures (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI) are shown in Table 1. The percentage of primiparas and babies with LBW are higher in IVF and ICSI procedures than FET-IVF and FET-ICSI.

Table 1.

Background characteristics and perinatal outcomes according to ART procedures (univariate p values obtained by GEE)

| Background characteristics (n = 2379 deliveries) | Total of missing data n (%) |

N | IVF (n = 860) | ICSI (n = 1114) | FET-IVF (n = 208) | FET-ICSI (n = 197) | p value |

| Values | Values | Values | Values | ||||

| Parental backgrounds | |||||||

| Maternal age (years) | 0 | 2379 | 33.3 (±4.2) | 32.5 (±4.5) | 33.7 (±4.3) | 32.7 (±4.2) | 0.07 |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 227 (9.5) | 2152 | 21.4 (±3.4) | 22.3 (±4.3) | 21.4 (±3.3) | 22.3 (±4.2) | <0.01a |

| Paternal age (years) | 0 | 2379 | 35.4 (±5.6) | 35.6 (±6.0) | 35.5 (±5.1) | 35.9 (±6.4) | 0.04a |

| Paternal BMI (kg/m2) | 579 (24.3) | 1800 | 24.5 (±3.4) | 24.7 (±3.3) | 24.5 (±3.2) | 25.2 (±3.6) | 0.22 |

| Maternal smoking behavior | 59 (2.5) | 2320 | 93 (11.1) | 118 (10.9) | 30 (14.4) | 33 (16.8) | 0.99 |

| DES daughter | 6 (0.3) | 2373 | 3 (0.4) | 7 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.31 |

| Preexisting diabetes | 6 (0.3) | 2373 | 1 (0.1) | 8 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.23 |

| Primipara | 6 (0.3) | 2373 | 765 (89.3) | 951 (85.4) | 136 (66.3) | 119 (60.4) | <0.01a |

| Biologic parameters | |||||||

| Day 5 of embryo transfer | 0 | 2379 | 372 (43.3) | 698 (62.7) | 76 (36.5) | 79 (40.1) | 0.87 |

| Over two embryos transferred | 0 | 2379 | 50 (5.8) | 56 (5.0) | 8 (3.8) | 10 (5.1) | 0.91 |

| Obstetric parameters | |||||||

| Placenta previa | 76 (3.2) | 2303 | 30 (3.7) | 32 (2.9) | 5 (2.6) | 3 (1.5) | 0.60 |

| High blood pressure induced by pregnancy | 76 (3.2) | 2303 | 50 (6.1) | 60 (5.5) | 14 (7.2) | 6 (3.1) | 0.13 |

| Gestational diabetes | 76 (3.2) | 2303 | 45 (5.5) | 61 (5.6) | 14 (7.2) | 11 (5.6) | 0.64 |

| Cesarean sectionb | 119 (5.1) | 2211 | 270 (34.2) | 353 (33.6) | 64 (34.4) | 59 (31.9) | 0.16 |

| Twin pregnancies | 0 | 2379 | 132 (15.3) | 185 (16.6) | 28 (13.5) | 26 (13.2) | 0.87 |

| Perinatal outcomes (n = 2750 babies and fetuses) | Total of missing data n (%) |

N | IVF (n = 992) | ICSI (n = 1299) | FET-IVF (n = 236) | FET-ICSI (n = 223) | p value |

| Values | Values | Values | Values | ||||

| Live births | 0 | 2686 | 964 (97.2) | 1272 (97.9) | 232 (97.8) | 218 (97.8) | 0.48 |

| Neonatal deaths | 8 | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Stillbirths | 25 | 13 (1.3) | 11 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | ||

| MTP | 31 | 13 (1.3) | 12 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| PTBc | 0 | 2694 | 189 (19.6) | 233 (18.3) | 37 (15.9) | 36 (16.4) | 0.14 |

| LBWc | 3 (0.1) | 2691 | 211 (21.8) | 276 (21.7) | 36 (15.5) | 35 (16.0) | 0.02a |

| Sex ratio (male/female)c | 0 | 2694 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.16 |

| All anomalies (yes) | 0 | 134 | 50 (5.0) | 68 (5.2) | 6 (2.5) | 10 (4.5) | 0.30 |

| Singleton | 88 | 37 (5.1) | 38 (4.1) | 4 (2.2) | 9 (5.3) | 0.28 | |

| Twins | 46 | 13 (4.9) | 30 (8.1) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.9) | 0.78 | |

Values are n (%) or mean (standard deviation)

IVF in vitro fertilization with standard insemination, ICSI in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection, FET frozen embryo transfer, BMI body mass index, DES daughter women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol, MTP medical terminations of pregnancy, PTB preterm birth (<37 weeks of gestational age), LBW low birth weight (<2500 g)

aStatistically significant result, p value < 0.05

bThis variable was evaluated only to live births and neonatal deaths (n = 2330 deliveries)

cThese variables were evaluated only to live births and neonatal deaths (n = 2694 babies and fetuses)

Etiological analysis: risk factors on congenital anomaly prevalence

The risks factors between babies and fetuses with and without congenital anomalies are shown in Table 2. The frequencies of twins, cesarean section, PTB, and LBW were higher in babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies than in babies and fetuses without congenital anomalies. The prevalence of congenital anomalies was not different between the four procedures (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI), even when adjusted for confounding factors.

Table 2.

Risk factors on congenital anomaly prevalence in babies and fetuses conceived after four ART procedures (univariate and multivariate logistic GEE)

| Background characteristics and perinatal outcomes 2750 babies and fetuses |

N | Babies and fetuses without congenital anomalies 2616 babies and fetuses Values |

Babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies 134 babies and fetuses Values |

Crude p value | Adjusted p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental backgrounds | |||||

| Maternal age (years) | 2750 | 32.8 (±4.3) | 32.9 (±5.1) | 0.80 | – |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 2473 | 21.9 (±3.9) | 22.2 (±4.0) | 0.45 | – |

| Paternal age (years) | 2750 | 35.5 (±5.7) | 36.0 (±7.2) | 0.41 | – |

| Paternal BMI (kg/m2) | 2039 | 24.7 (±3.4) | 24.4 (±3.0) | 0.27 | – |

| Maternal smoking behavior | 2687 | 293 (11.4) | 9 (7.5) | 0.18 | – |

| DES daughter | 2744 | 12 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | 0.74 | – |

| Preexisting diabetes | 2744 | 11 (0.4) | 0 | NA | – |

| Primipara | 2744 | 2181 (83.5) | 106 (79.7) | 0.21 | – |

| Biologic parameters | |||||

| Day 5 of embryo transfer | 2750 | 1322 (50.5) | 67 (50.0) | 0.90 | – |

| Over two embryos transferred | 2750 | 146 (5.6) | 6 (4.5) | 0.80 | – |

| Obstetric parameters | |||||

| Placenta previa | 2661 | 73 (2.9) | 6 (4.5) | 0.42 | – |

| High blood pressure induced by pregnancy | 2661 | 171 (6.8) | 4 (3.0) | 0.09 | – |

| Gestational diabetes | 2661 | 148 (5.9) | 5 (3.8) | 0.32 | – |

| Cesarean sectionb | 2555 | 927 (37.6) | 47 (51.1) | 0.03a | – |

| Twins | 2750 | 696 (26.6) | 46 (34.3) | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Perinatal outcomes | |||||

| Live births n (%) | 2750 | 2588 (98.9) | 98 (73.1) | <0.01a | – |

| Neonatal deaths | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Stillbirths and MTP | 21 (0.8) | 35 (26.1) | |||

| PTBb | 2694 | 466 (18.0) | 29 (29.3) | <0.01a | – |

| LBWb | 2691 | 528 (20.4) | 30 (30.9) | 0.08 | – |

| Sex ratio (male/female)b | 2694 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.35 | – |

| Procedures | |||||

| IVF | 2750 | 942 (36.0) | 50 (37.3) | 0.39 | 0.40 |

| ICSI | 1231 (47.1) | 68 (50.7) | |||

| FET-IVF | 230 (8.8) | 6 (4.5) | |||

| FET-ICSI | 213 (8.1) | 10 (7.5) | |||

Values are n (%) or mean (standard deviation). The statistical unit was the babies and fetuses. IVF in vitro fertilization with standard insemination, ICSI in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection, FET frozen embryo transfer, BMI body mass index, DES daughter women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol, MTP medical terminations of pregnancy, PTB preterm birth (<37 weeks of gestational age), LBW low birth weight (<2500 g), NA statistical test not applicable

Adjusted analysis: Twins

aStatistically significant result, p value < 0.05

bThese variables were evaluated only to live births and neonatal deaths (n = 2694 babies and fetuses)

Description of congenital anomalies

The descriptions and the frequencies of congenital anomalies in the four groups are shown in Table 3. Among the 134 babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies, the major prevalences concerned the congenital heart defects (22.4%), the chromosomal anomalies (16.4%), and the urinary defects (11.9%).

Table 3.

Description of the number of cases and prevalence of congenital anomalies according to EUROCAT classification in the four groups (2001–2014)

| Congenital anomalies of 134 babies and fetuses | IVF n = 992 |

ICSI n = 1299 |

FET-IVF n = 236 |

FET-ICSI n = 223 |

Total prevalence [95% CI] n = 2750 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All anomalies (yes) | 50 (5.0) | 68 (5.2) | 6 (2.5) | 10 (4.5) | 4.9 (4.1–5.7) |

| Congenital heart defects (CHD) | 7 (0.3) | 19 (0.7) | 1 (0.01) | 3 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) |

| Severe CHD | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Double outlet right ventricle | 0 | 1 (0.025) | 0 | 0 | |

| Transposition of great vessels | 0 | 1 (0.025) | 0 | 1 (0.033) | |

| Ventricular septal defect | 0 | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Atrial septal defect | 2 (0.1) | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.01) | 0 | |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | 0 | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.033) | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 1 (0.033) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | 0 | 1 (0.025) | 0 | 0 | |

| Pulmonary valve atresia | 1 (0.033) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mitral valve anomalies | 1 (0.033) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other causes | 0 | 1 (0.025) | 0 | 1 (0.033) | |

| Chromosomal | 9 (0.3) | 11 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| Down syndrome | 4 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.1) | |

| Patau syndrome | 1 (0.033) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Edward syndrome | 1 (0.033) | 1 (0.01) | 0 | 0 | |

| Turner syndrome | 1 (0.033) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Other causes | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Urinary | 9 (0.3) | 6 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.01) | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) |

| Congenital hydronephrosis | 8 (0.26) | 6 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.01) | |

| Bladder exstrophy and/or epispadia | 1 (0.04) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nervous system | 3 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) | 1 (0.01) | 2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Eyes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.01) | <0.01 (0.01–0.1) |

| Respiratory | 0 | 1 (0.01) | 0 | 0 | <0.01 (0.01–0.1) |

| Orofacial clefts | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.01) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 (0.01–0.3) |

| Digestive system | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.01) | 0 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) |

| Genital | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) |

| Limb | 8 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.01) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) |

| Other anomalies/syndromes | 6 (0.2) | 8 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) |

Values are n (%)

IVF in vitro fertilization with standard insemination, ICSI in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection, FET frozen embryo transfer

Discussion

The present study compared the prevalence of congenital anomalies found in four groups of fetuses/babies of our ART center (IVF, ICSI, FET-IVF, and FET-ICSI) between 2001 and 2014.

Our results suggested that there was no difference in congenital anomalies between these four procedures (p = 0.39), even when adjusted for confounding factors (p = 0.40) (Table 2).

The background characteristics and the perinatal outcomes in fetuses/babies conceived using one of the four studied ART procedures did not show significant statistical differences (except for maternal BMI, paternal age, the prevalence of primiparas, and LBW) (Table 1). The increased prevalence of primiparas in the IVF and ICSI procedures compared to FET-IVF and FET-ICSI procedure could be coherent with patients’ profile. In fact, women receiving a FET frequently come to achieve a second pregnancy, which explains the low prevalence of primiparas in this group. The rise of LBW in the IVF and ICSI procedures is in line with the literature. Indeed, Pinborg and collaborators highlighted that FET children have a lower risk of LBW than children born after fresh embryo transfer [23].

A sensitivity analysis was performed to rule out any biases potentially introduced by the evolution of procedures in our center. Indeed, in 2004, we introduced major changes in our daily practice that has been consistent since then: all embryos are cultured under the same conditions, no more than two embryos are proposed for intrauterine transfer and blastocyst stage embryo transfer is privileged. Therefore, the sensitivity analysis included only babies and fetuses conceived from 2004 to 2014 and did not show any difference between the four studied procedures. Data found in the present study are in line with the literature questioning the health of IVF children as compared to ICSI ones [12, 15, 38] and children born after fresh versus frozen embryo transfer [20, 22, 39].

A supplementary analysis was performed to assess the differences in outcome between fresh embryos transfer compared to frozen embryos transfer. No significant difference was observed in prevalence of babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies versus babies and fetuses without congenital anomalies (p = 0.16), even when adjusted for the same confounding factors (p = 0.17) (Supplemental Table 1).

These results also showed that micromanipulation (ICSI) and ovarian stimulation did not impact the malformation prevalence. At the same time, our results suggested that there is no increased risk of congenital anomalies after blastocyst transfer compared to cleavage-stage transfer (p = 0.90) (Table 2).

The prevalence of congenital anomalies in the French EUROCAT population was 2.7%, between 2001 and 2014 [6]. In our population, the prevalence in the four procedures was 4.9% for all congenital anomalies, which could support the fact that ART children are more at risk to develop congenital anomalies [12, 40]. Seggers and colleagues have evaluated the prevalence in each subgroup of congenital anomalies, between a subfertility group (139 conceptions after IVF/ICSI and 201 natural conceptions) and a fertile group (4185 conceptions) [41]. Their results showed an increased risk to polydactyly hand in conception after IVF/ICSI versus the subfertility conceived naturally (OR 2.78, 95% CI 1.53–5.07). Additionally, they found a higher risk of abdominal wall defects (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.05–5.62), penoscrotal hypospadias (OR 9.83, 95% CI 3.58–27.04), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.06–2.97) in the subfertility group versus fertile group. The major prevalences in our sample were found in congenital heart defects (1.1 95% CI [0.7–1.5]), chromosomal anomalies (0.8 95% CI [0.5–1.2]), and urinary defects (0.6 95% CI [0.3–0.9]). However, it is crucial to compare our results with a control group before being able to draw any definitive conclusion.

Our results were not representative of ART centers at the national level, particularly in terms of number of embryo transferred. The number of single embryo transferred is more important in our center than in the national average of ART centers (59.9% vs. 37.2%). This point explains the lower percentage of twin deliveries in our center than national average (9.4% vs. 15.9%) [26, 42].

We are conscious that geographic characteristics, such as lifestyle, environmental parameters, and the socioeconomic conditions, could affect patients’ clinical results. However, medically assisted reproduction (MAR) has a specific legislation in France. The French national health insurance system provides heterosexual couples reimbursement up to 100% of ART procedure expenses. This allows every couple regardless their socioeconomic situation to benefit MAR treatment, which limits the difference between our population and that of other fertility centers in France. According to the report published in 2013 by French Biomedicine Agency, our clinical and biological characteristics are similar to the ones of the national average of ART centers (maternal age 34.6 vs. 34.4 years in the national average of ART centers, mean number of oocytes retrieved 8.3 vs. 8.7, couples without any viral pathology 100% vs. 98.2%, pregnancies after fresh embryo transfer 26.1% vs. 25.6%).

In the analysis of risk factors on congenital anomaly prevalence in the present study, it appeared that twins were more often observed in the group of babies and fetuses with congenital anomalies. This explains the higher prevalence in cesarean section, preterm, and low birth weight in this group. This observation provides a major argument to support our single embryo transfer policy. Indeed, it was shown in the report published in 2013 that our prevalence of twins is lower than in French ART population. In fact, limiting multiple pregnancies minimizes complications during pregnancy and improves the health of children [43]. It would be interesting to investigate this factor in a multicenter analysis and adjust it for confounding factors.

One of the strengths of this study was the coding of congenital anomalies in the EUROCAT classification. This classification was ensured by the medical doctor in charge of the children follow-up [34]. Embryological medical control and validation of the information were assessed in all the obtained reports or copies of the personal child health record document. Diagnosis of congenital anomalies was established after a medical examination to ensure a high quality of data.

Moreover, our study included all fetuses from the medical terminations that were made in most cases by a congenital anomaly. The inclusion of babies and fetuses allowed an exhaustive description of our population. However, some birth defects remain undiagnosed in the neonatal period. Our experience following up these children in the long term allowed verifying that the congenital anomalies included in the EUROCAT classification were diagnosed in the neonatal period and not at later ages [33]. The congenital anomalies diagnosed at later ages, after the neonatal period, were not included in the EUROCAT classification.

Another strength of our study was the selection of confounding factors, which have been identified to have an effect on congenital anomalies or affect the results of the other studies [17, 44–46].

It would be more pertinent to compare our data with a group of naturally conceived children, with the EUROCAT Register, and evaluate these anomalies during the neonatal period and at later ages. Nevertheless, our preliminary results are in line with the epidemiological studies that have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular anomalies and urogenital and genetic defects for babies of infertile couples [40, 47]. This point could be considered in a future study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggested that the prevalence of congenital anomalies was not different between fresh or frozen embryo transfer after IVF or ICSI. Consistently with the literature [48], our data showed that the transfer of only one embryo improves the health of the offspring. Our policy allowed over the past 20 years a progressive decrease in the rate of twins delivery to 10% in the last 7 years, while to the national rate was 17.4% in 2011 [49]. The association of single embryo transfer policy and the development of cryobiology turns out to be an interesting way to limiting malformation prevalence in children conceived in ART program.

Electronic supplementary material

Reliability rate of congenital anomalies data, blastocyst transfer rate, twin deliveries rate, and mean number of embryo transferred between 1994 and 2014 (GIF 184 kb)

(DOCX 25 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

No external funding was obtained for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Data used to conduct the present study were obtained in accordance with French Bioethics Law. This study did not require ethic committee approval. For this type of study format, consent is not required.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-017-0903-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1978;2:366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem AC. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet Lond. Engl. 1992;340:17–18. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, Solà I, Geber S, Carreras R, et al. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nygren K-G, Finnström O, Källén B, Olausson PO. Population-based Swedish studies of outcomes after in vitro fertilisation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:774–782. doi: 10.1080/00016340701446231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brison DR, Roberts SA, Kimber SJ. How should we assess the safety of IVF technologies? Reprod BioMed Online. 2013;27:710–721. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EUROCAT—European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies. Number of cases and prevalence per 10,000 births of all anomalies, for all full member countries, from 1980–2012. 2015. http://www.eurocat-network.eu/accessprevalencedata/prevalencetables. Accessed 25 Apr 2016

- 7.Boyd PA, Haeusler M, Barisic I, Loane M, Garne E, Dolk H. Paper 1: the EUROCAT network—organization and processes†. Birt Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:S2–15. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancaster PA. Health registers for congenital malformations and in vitro fertilization. Clin Reprod Fertil. 1986;4:27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimm AA, Katayama AC, Diaz M, Katayama KP. A meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing major malformation rates in IVF and ICSI infants with naturally conceived children. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2004;21:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s10815-004-8760-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonduelle M, Wennerholm U-B, Loft A, Tarlatzis BC, Peters C, Henriet S, et al. A multi-centre cohort study of the physical health of 5-year-old children conceived after intracytoplasmic sperm injection, in vitro fertilization and natural conception. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2005;20:413–419. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson CK, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Romitti PA, Budelier WT, Ryan G, Sparks AET, et al. In vitro fertilization is associated with an increase in major birth defects. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1308–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Källén B, Finnström O, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren K-G, Otterblad PO. Congenital malformations in infants born after in vitro fertilization in Sweden. Birt Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:137–143. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen SW, Leader A, White RR, Léveillé M-C, Wilkie V, Zhou J, et al. A comprehensive assessment of outcomes in pregnancies conceived by in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen M, Kurinczuk JJ, Milne E, de Klerk N, Bower C. Assisted reproductive technology and birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:330–353. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wen J, Jiang J, Ding C, Dai J, Liu Y, Xia Y, et al. Birth defects in children conceived by in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wennerholm UB, Albertsson-Wikland K, Bergh C, Hamberger L, Niklasson A, Nilsson L, et al. Postnatal growth and health in children born after cryopreservation as embryos. Lancet Lond Engl. 1998;351:1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Källén B, Finnström O, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. In vitro fertilization (IVF) in Sweden: risk for congenital malformations after different IVF methods. Birt. Defects Res. A. Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2005;73:162–169. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belva F, Henriet S, Van den Abbeel E, Camus M, Devroey P, Van der Elst J, et al. Neonatal outcome of 937 children born after transfer of cryopreserved embryos obtained by ICSI and IVF and comparison with outcome data of fresh ICSI and IVF cycles. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2008;23:2227–2238. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aflatoonian A, Mansoori Moghaddam F, Mashayekhy M, Mohamadian F. Comparison of early pregnancy and neonatal outcomes after frozen and fresh embryo transfer in ART cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:695–700. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinborg A, Loft A, Aaris Henningsen A-K, Rasmussen S, Andersen AN. Infant outcome of 957 singletons born after frozen embryo replacement: the Danish National Cohort Study 1995-2006. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1320–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wennerholm U-B, Henningsen A-KA, Romundstad LB, Bergh C, Pinborg A, Skjaerven R, et al. Perinatal outcomes of children born after frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a Nordic cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2013;28:2545–2553. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maheshwari A, Pandey S, Shetty A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from the transfer of frozen thawed versus fresh embryos generated through in vitro fertilization treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinborg A, Henningsen AA, Loft A, Malchau SS, Forman J, Andersen AN. Large baby syndrome in singletons born after frozen embryo transfer (FET): is it due to maternal factors or the cryotechnique? Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2014;29:618–627. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelkonen S, Hartikainen A-L, Ritvanen A, Koivunen R, Martikainen H, Gissler M, et al. Major congenital anomalies in children born after frozen embryo transfer: a cohort study 1995-2006. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2014;29:1552–1557. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Mouzon J, Bachelot A, Spira A. Establishing a national in vitro fertilization registry: methodological problems and analysis of success rates. Stat Med. 1993;12:39–50. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FIVNAT Pregnancies and births resulting from in vitro fertilization: French national registry, analysis of data 1986 to 1990. FIVNAT (French In Vitro National) Fertil Steril. 1995;64:746–756. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)57850-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivennes F, Schneider Z, Remy V, Blanchet V, Kerbrat V, Fanchin R, et al. Perinatal outcome and follow-up of 82 children aged 1-9 years old conceived from cryopreserved embryos. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 1996;11:1565–1568. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivennes F, Kerbrat V, Rufat P, Blanchet V, Fanchin R, Frydman R. Follow-up of a cohort of 422 children aged 6 to 13 years conceived by in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:284–289. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epelboin S. Children born of ICSI. J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod. 2007;36(Suppl 3):S109–S113. doi: 10.1016/S0368-2315(07)78742-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sagot P, Bechoua S, Ferdynus C, Facy A, Flamm X, Gouyon JB, et al. Similarly increased congenital anomaly rates after intrauterine insemination and IVF technologies: a retrospective cohort study. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2012;27:902–909. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassuto NG, Hazout A, Bouret D, Balet R, Larue L, Benifla JL, et al. Low birth defects by deselecting abnormal spermatozoa before ICSI. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agence de la Biomédecine. Le rapport annuel médical et scientifique 2014. 2014a. http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/annexes/bilan2014/donnees/sommaire-proc.htm. Accessed 16 Mar 2016

- 33.Boyer M, Meddeb L, Pauly V, Boyer P. Suivi des enfants de l’AMP: Expérience d’un centre français. Physiol. Pathol. Thérapie Reprod. Chez L’humain. Paris: Springer; 2011. pp. 665–676. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meddeb L, Boyer M, Pauly V, Tourame P, Rossin B, Pfister B, et al. Procedure used to follow-up a cohort of IVF children. Interests and limits of tools performed to longitudinal follow up for a monocentric cohort. Rev Dépidémiologie Santé Publique. 2011;59:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anzola AB, Pauly V, Geoffroy-Siraudin C, Gervoise-Boyer M-J, Montjean D, Boyer P. The first 50 live births after autologous oocyte vitrification in France. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:1781–1787. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0603-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merlet F. Regulatory framework in assisted reproductive technologies, relevance and main issues. Folia Histochem Cytobiol Pol Acad Sci Pol Histochem Cytochem Soc. 2009;47:S9–12. doi: 10.2478/v10042-009-0048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer P, Boyer M. Non invasive evaluation of the embryo: morphology of preimplantation embryos. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertil. 2009;37:908–916. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lie RT, Lyngstadaas A, Ørstavik KH, Bakketeig LS, Jacobsen G, Tanbo T. Birth defects in children conceived by ICSI compared with children conceived by other IVF-methods; a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:696–701. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wennerholm U-B, Söderström-Anttila V, Bergh C, Aittomäki K, Hazekamp J, Nygren K-G, et al. Children born after cryopreservation of embryos or oocytes: a systematic review of outcome data. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2009;24:2158–2172. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies MJ, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Van Essen P, Priest K, Scott H, et al. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seggers J, de Walle HEK, Bergman JEH, Groen H, Hadders-Algra M, Bos ME, et al. Congenital anomalies in offspring of subfertile couples: a registry-based study in the northern Netherlands. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Agence de la Biomédecine. Le rapport annuel médical et scientifique 2014. 2014b. http://www.agence-biomedecine.fr/annexes/bilan2014/donnees/sommaire-proc.htm. Accessed 19 Jan 2017.

- 43.Sazonova A, Källen K, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Wennerholm U-B, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcomes comparing women undergoing two in vitro fertilization (IVF) singleton pregnancies and women undergoing one IVF twin pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:731–737. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Wright C. Congenital anomalies in twins: a register-based study. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2008;23:1306–1311. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalfa N, Paris F, Soyer-Gobillard M-O, Daures J-P, Sultan C. Prevalence of hypospadias in grandsons of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy: a multigenerational national cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2574–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tournaire M, Epelboin S, Devouche E, Viot G, Le Bidois J, Cabau A, et al. Adverse health effects in children of women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol (DES) Therapie. 2016;71:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ESHRE Capri Workshop Group Birth defects and congenital health risks in children conceived through assisted reproduction technology (ART): a meeting report. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2014;31:947–958. doi: 10.1007/s10815-014-0255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grady R, Alavi N, Vale R, Khandwala M, McDonald SD. Elective single embryo transfer and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.European IVF-Monitoring Consortium (EIM), European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Kupka MS, D’Hooghe T, Ferraretti AP, de Mouzon J, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2011: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2016;31:233–248. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reliability rate of congenital anomalies data, blastocyst transfer rate, twin deliveries rate, and mean number of embryo transferred between 1994 and 2014 (GIF 184 kb)

(DOCX 25 kb)