Abstract

In crop plants, a high-density genetic linkage map is essential for both genetic and genomic researches. The complexity and the large size of wheat genome have hampered the acquisition of a high-resolution genetic map. In this study, we report a high-density genetic map based on an individual mapping population using the Affymetrix Wheat660K single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array as a probe in hexaploid wheat. The resultant genetic map consisted of 119 566 loci spanning 4424.4 cM, and 119 001 of those loci were SNP markers. This genetic map showed good collinearity with the 90 K and 820 K consensus genetic maps and was also in accordance with the recently released wheat whole genome assembly. The high-density wheat genetic map will provide a major resource for future genetic and genomic research in wheat. Moreover, a comparative genomics analysis among gramineous plant genomes was conducted based on the high-density wheat genetic map, providing an overview of the structural relationships among theses gramineous plant genomes. A major stable quantitative trait locus (QTL) for kernel number per spike was characterized, providing a solid foundation for the future high-resolution mapping and map-based cloning of the targeted QTL.

Introduction

High-density genetic linkage maps are essential for genetic and genomic research in crops1–4. Molecular breeding is more effective if the molecular map is dense to provide more choices in the quality and type of markers and to increase the probability of detecting polymorphic markers in important chromosomal intervals. In wheat, the large genome size (17 gigabases), hexaploid nature (AABBDD), high percentage of repetitive regions and low level of polymorphism have complicated the acquisition of high-resolution genetic maps by molecular markers1–4. To date, several kinds of molecular markers, including restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)5, 6, amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)7, simple sequence repeats (SSRs)8, 9, and diversity array technology (DArT)3, 4, 10, 11 have been used to construct genetic linkage maps in wheat. Information regarding wheat molecular markers and genetic maps is available in some datasets such as GrainGenes 2.0 (https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/), URGI (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/), etc. Most of these markers are mapped on the telomeric regions, and there is very limited map resolution in proximal part of the chromosomes3. Therefore, the density and coverage of the current genetic maps are less than satisfactory.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most abundant type of molecular marker. Accurate and reliable methods have been developed to perform high-throughput genotyping based on SNPs12. With the development of new sequencing technologies, increasing numbers of SNPs have been discovered in wheat1, 2, 13–15. Cavanagh et al.12 released a hexaploid wheat consensus genetic map with 7504 SNP markers from the Wheat9K SNP array using a combination of seven mapping populations. Wang et al.16 mapped 46977 SNPs from the Wheat90K array to the hexaploid wheat genetic map using a combination of eight mapping populations. Using both Wheat9K and Wheat90K arrays, Maccaferri et al.17 released a high-density tetraploid wheat consensus genetic map with 30144 markers (including 26626 SNPs and 791 SSRs) by integrating 13 data sets from independent biparental mapping populations. Recently, Winfield et al.18 documented a hexaploid wheat consensus map with 56 505 SNP markers from the Wheat820K array, spanning 3739 cM in length, using three independent biparental populations. However, although a high-density hexaploid wheat genetic map (>100 000 markers) based on an individual biparental mapping population would be valuable for further genetic research, such as high-resolution mapping and map-based cloning of a targeted major quantitative trait locus (QTL), no such map has been released.

A new Whole Genome Shotgun (WGS) assembly of the Chinese Spring (CS) reference wheat genome is now available (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html; https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/). However, genetic and genomic studies in wheat continue to lag behind the research in other members of the grass family (Gramineae), such as rice and maize. The gradual enrichment of SNP markers and the sequences released for CS (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/), Triticum urartu 2 and Aegilops tauschii 1 have facilitated comparative genomic analysis in wheat. Comparative genomic analysis with species whose genomes have been well characterized has been used as an effective method for the construction of high-resolution genetic linkage maps of target wheat genes and for the prediction of candidate genes in regions of interest. For instance, the construction of high-density genetic maps has facilitated the mapping of the gene grain protein content-B1 (Gpc-B1)19, the yellow rust resistance gene Yr36 20 and the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm41 21. Comparative genomics studies have also furthered the understanding of the basic processes of genome evolution and the transfer of information from model species to related organisms and facilitated the cross-referencing of various types of information, such as QTLs, mutants, and gene expression22, 23. These correlations and integrations will take full advantage of the collective intellectual contributions from scientists across many disciplines22.

Wheat660K, the Affymetrix® Axiom® Wheat660, was designed by the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and synthesized by Affymetrix. This Wheat660K SNP array is genome-specific with high density and is highly efficient with a wide range of potential applications (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/ggpages/topics/Wheat660_SNP_array_developed_by_CAAS.pdf). However, genetic position in relation to Wheat660K SNPs has not yet been documented. In this work, for the first time, we report a high-density map for wheat constructed from this Wheat660K SNP Array. Based on SNP flanking sequences, we assigned SNPs to the genome assembly of T. aestivum cv. Chinese Spring (CS) (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/). We also compared our high-density genetic map with the consensus genetic maps of Wheat90K and Wheat820K based on the common contigs assembled in the chromosome survey sequencing (CSS) project. Comparative genomic analyses based on the mapped SNP flanking sequences and the corresponding contig sequences were also performed with the genomes of Brachypodium distachyon, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, and Sorghum bicolor. Using this mapping resource along with the phenotypic data, we identified important QTLs for yield-related trait. A major stable QTL for kernel number was identified and then characterized in detail based on the high-density genetic map and comparative genomic analysis.

Results

SNP scores in the 265 accessions

An F8:9 recombinant inbred line (RIL) population including 188 lines derived from a cross between Kenong 9204 (KN9204) and Jing 411 (J411) (denoted as KJ-RILs), 65 KN9204-derived advanced lines/authorized varieties, three parental lines of KN9204, three control varieties from the Winter Wheat Performance Trial of the Northern Huang-Huai Regional Nursery of China, and Chinese Spring (CS) were genotyped using the 630517 SNPs on the Wheat660K SNP array as probes. The sample call rates ranged from 18.6% to 100.0%, with an average of 98.9% for the 265 accessions (data not shown). The scores for the probes were classified into one of the following six categories according to the cluster patterns produced by the Affymetrix software (Table S1): (i) Poly High Resolution (PHR) (188040; 29.8%); (ii) No Minor Homozygote (NMH) (133246; 21.1%); (iii) Off-Target Variant (OTV) (18471; 3.0%); (iv) Mono High Resolution (MHR) (163308; 25.9%); (v) Call Rate Below Threshold (CRBT) (22635; 3.6%); and (vi) Other (91425, 14.5%). Only the first three groups (PHR, NMH and OTV) were considered useful, and they accounted for 53.9% of the Wheat660K SNP array probes.

Of the 339757 functional SNPs, 136973 (40.3%) were polymorphic between KN9204 and J411. Of these, 8407 had more than 10% missing data in the 188 KJ-RILs, and were removed from the linkage analysis. Among the remaining 128566 SNPs, 90567 (70.4%) were transitions, and 37999 (29.6%) were transversions. The 128566 functional SNPs and the previously reported 591 loci3 were used for linkage analysis and map construction. The 129157 markers fell into 5175 bins, and to create a chromosome frame, only one marker was selected as a representative from each bin.

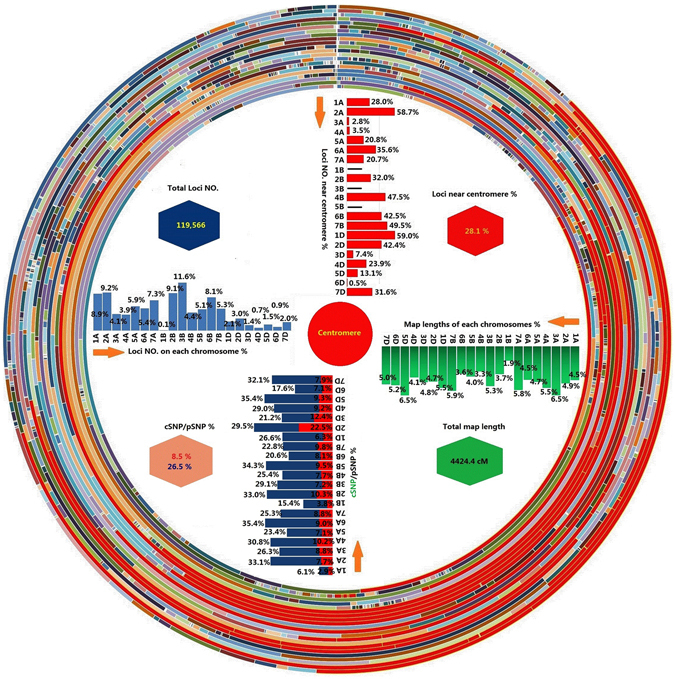

Overview of the high-density wheat genetic map

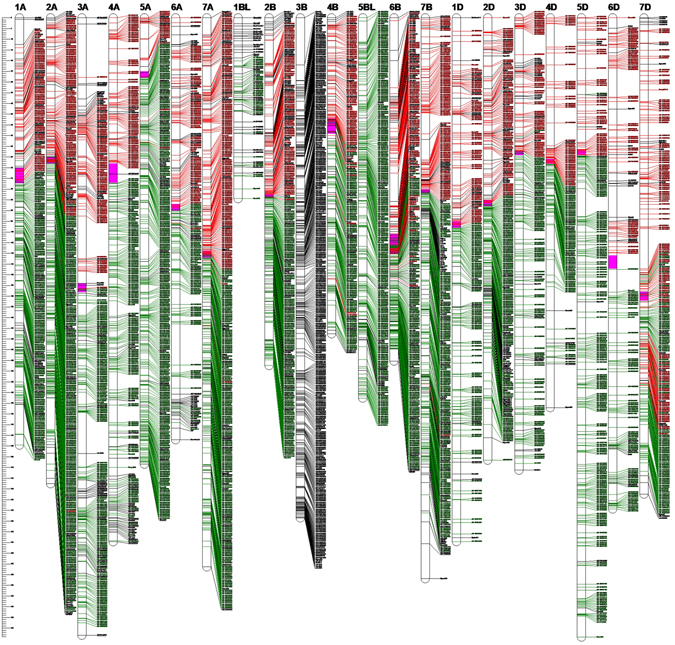

The 5175 bin markers were used for linkage analysis based on their scores in the 188 KJ-RILs. In total, 4959 bin markers were mapped to the wheat genetic map. The co-segregated markers (redundant markers) were then added to the high-density genetic map based on information of bin serial number and the genetic information of the corresponding bin markers. A high-density genetic map with 119566 loci spanning 4424.4 cM was constructed (Table S2). Of these loci, 119001 were SNP markers derived from the Wheat660K SNP array, and the remaining 565 markers were reported previously by Cui et al.3. Of the 119001 SNPs, 83953 (70.5%) were transitions, and 35048 (29.5%) were transversions (data not shown). Most markers were mapped to the B (44.6%) and A genomes (43.7%), and only 11.7% markers were mapped to the D genome. For the map lengths, the A, B, and D genomes covered 36.4%, 27.7%, and 35.8% of the total map length, respectively. The chromosome sizes ranged from 84.4 cM (chromosome 1BL) to 289.1 cM (chromosome 5D), averaging 210.7 cM per chromosome. The number of markers on each chromosome ranged from 78 (chromosome 1BL) to 13898 (chromosome 3B), with a mean of 5693.6 loci per chromosome. Due to the 1BL/1RS translocation of KN9204, the 1RS- or 1BS-specific markers not only showed co-segregation but also exhibited distorted segregation in the KJ-RILs as shown by Cui et al.3. These markers were excluded from the linkage analysis and map construction, which reduced the genetic maps for analysis to 1BL only. In addition, no markers on chromosome 5BS were polymorphic between KN9204 and J411, resulting in the release of the 5BL genetic map only. Of the 119566 loci, 33598 (28.1%) were distributed on chromosomal regions near the centromeres. Marker density per genetic distance unit peaked at the centromeric regions, possibly due to a combination of low recombination rate in the centromeric regions and even gene distribution along the chromosomes (Fig. 1). The 4 959 bin markers are shown in the genetic map (Fig. 2). The following mapping-bin sets were observed: approximately 3.7% and 3.2% of the markers were unique for genomes A and B, respectively, and approximately 9.6% of the markers for the D genome showed unique segregation patterns.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the 119 566 loci on the 21 wheat chromosomes. The 21 circles indicate the 21 wheat chromosomes, with 7D to 1D, 7B to 1B, and 7A to 1A from inside to outside, respectively. Each chromosome was evenly divided into 100 segments based on the map length, which are shown with different colours. The arc lengths indicate the percentage of markers on each segment (The total number of markers on the corresponding chromosome divided by the number of markers on the segments). The arc in red colour indicates the chromosomal bins near the centromere. The upper left histogram in the circle indicates the distribution of markers on each chromosome; the upper right histogram in the circle indicates the distribution of markers near the centromere on each chromosome; the bottom right histogram in the circle indicates the distribution of map length on each chromosome; the bottom left histogram in the circle indicates the distribution of markers in/near the coding sequences.

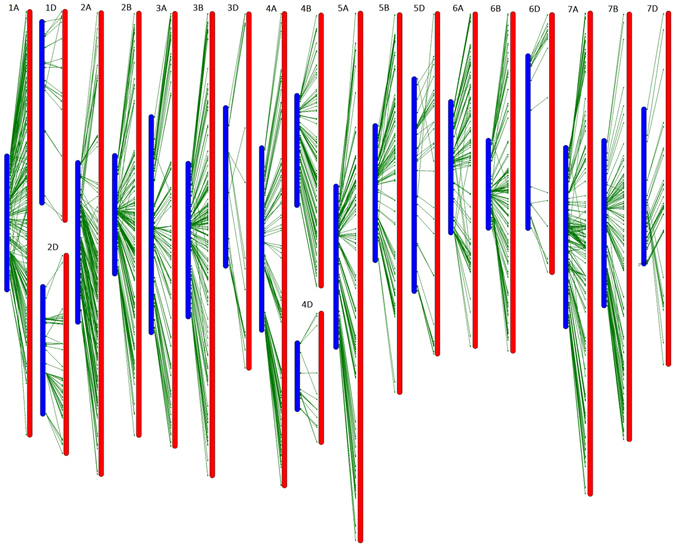

Figure 2.

The high-density genetic map of wheat developed using an RIL population derived from the cross of cultivars KN9204 and J411. For the redundant loci that showed co-segregation in the 188 KJ-RILs, only one unique informative marker is shown in this figure. The approximate positions of the centromeres are indicated by pink. Short arms are at the top. The positions of the marker loci are indicated using a ruler on the left side of this figure. The names of the marker loci are listed to the right of the corresponding chromosomes. Loci in red were best hits to Chinese Spring (CS) contigs of the short arm of the corresponding chromosomes. Loci in green were best hits to CS contigs of the long arm of the corresponding chromosomes. Loci in black were unknown. Contigs from chromosome 3B were not separated into short/long arm bins, as individual arm datasets were not generated for this chromosome in the Chromosome Survey Sequence (CSS) project.

Considering the unique markers (the 4 959 bin markers), the highest marker saturation was found in genome A (39.3%), followed by genomes B (33.6%) and D (27.1%). The average distance between adjacent bin markers ranged from 0.6 cM for 6B to 1.5 cM for 4D, with an average of 0.9 cM per marker pair. Gaps greater than 20.0 cM but less than 30.0 cM were present in chromosomes 3 A (24.9 cM), 3B (21.9 cM) and 4D (20.4 cM); gaps greater than 10 cM but less than 20.0 cM were present in chromosomes 1 A (13.9 cM, 11.7 cM), 2 A (14.6 cM), 2B (10.6 cM), 2D (10.5 cM), 3 A (19.9 cM, 19.2 cM), 3D (12.1 cM), 4D (11.5 cM, 11.2 cM, 11.0 cM, 11.0 cM), 5 A (12.1 cM), 5D (13.2 cM), 6 A (19.2 cM), 6B (13.8 cM, 13.2 cM, 12.7 cM), 6D (14.6 cM, 13.6 cM, 10.9 cM, 10.7 cM), 7B (16.3 cM, 10.1 cM), and 7D (18.8 cM) (Fig. 2).

Comparative genomic analysis

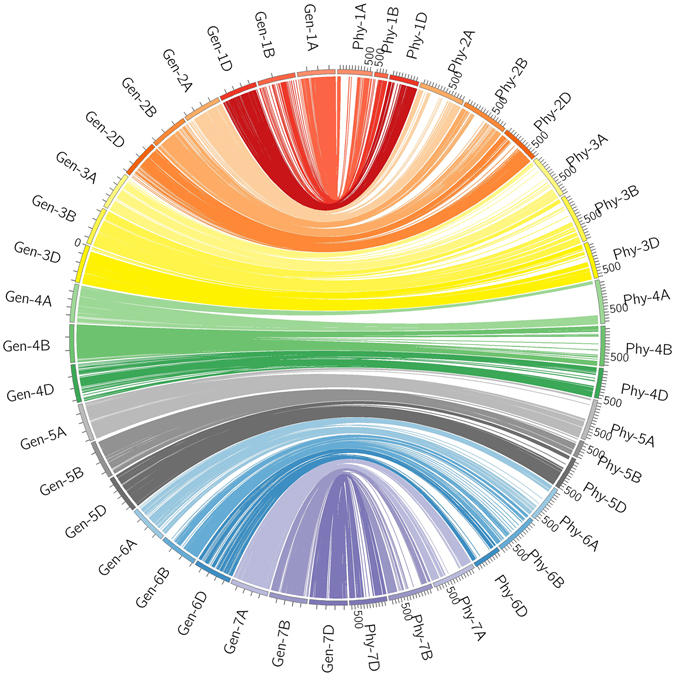

Of the 119566 loci, 118998 (99.5%) were best hits to 57036 CSS contigs, with 2.1 polymorphic markers per contig. In total, 93.0% contigs had coincident physical and genetic positions, 4.6% were mapped to homoeologous chromosomes such as 1 A in physical position and 1B in the KJ-RIL genetic map, and 2.4% were disordered (Fig. 2; Figure S1; Table S3). Based on the SNP flanking sequences, we assigned 116 261 SNPs to the recently released wheat genome assembly. SNP order in the present genetic map was in good agreement with that in the wheat genome assembly, with the exception of chromosome 7DL, in which a segment inversion was identified (Fig. 3; Figure S2; Table S3).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the syntenic relationships between any one marker in wheat genetic and physical maps. Gen-1A to Gen-7D represent the 21 wheat chromosomal genetic maps released in this paper; Phy-1A to Phy-7D represent the 21 wheat chromosomal physical maps, which were constructed by assigning 116 261 SNPs to the wheat genome assembly using SNP flanking sequences as the query. For the redundant loci that showed co-segregation in the 188 KJ-RILs, only one unique informative marker is shown in this figure.

An overview (from the wheat genetic map perspective) of the relationships between the five grass family genomes at the resolution of the genetic map in centimorgans is provided in Figures S3 and S4. There were 113288 markers that corresponded to the CDS of Brachypodium (65357 markers) (Table S4; Figure S3a, S4a), rice (58825 markers) (Table S4; Figures S3b, S4b), maize (53745 markers) (Table S4; Figures S3c, S4c), and sorghum (59994 markers) (Table S4; Figures S3d, S4d). In general, chromosomes belonging to the same homoeologous groups showed correspondence with the same grass chromosomes, but some differences were observed. Large and especially small synteny blocks across wheat and grass family chromosomes were observed, indicating the complexity of the wheat genome among the grass family genomes. The structural relationships among the genomes indicate that for some individual wheat chromosomes, there is a preponderance of corresponding grass genes from one or two certain linkage groups. For example, wheat chromosomes 2 A/2B/2D corresponded to Bd5, wheat chromosomes 3 A/3D corresponded to Bd2 and Bd3, wheat chromosomes 4 A/4B/4D corresponded to Os3, and wheat chromosomes 7 A/7B/7D corresponded to Sb10. However, for most synteny blocks, the chromosomes were more fragmented and scattered, with a high frequency of breakdown.

To specify the coding-region SNPs (cSNPs), perigenic SNPs (pSNPs), and intergenic SNPs (iSNPs) among the SNP markers mapped in the KJ-RIL genetic map, a BLASTX search was performed against the CDS of T. aestivum, using SNP flanking sequences and the corresponding contig sequences as queries. Using SNP flanking sequences as the query, 8.9% (10104 SNPs) were best hits to the CDSs of the T. aestivum, and these were considered to be the cSNPs. When using the contig sequences where the markers were best hits to as the query, approximately 36.8% (41689 SNPs) were best hits for the CDSs of the T. aestivum, indicating that 27.9% (36.8–8.9%) of SNPs were pSNPs. The remaining 63.2% are likely iSNPs (Table S5).

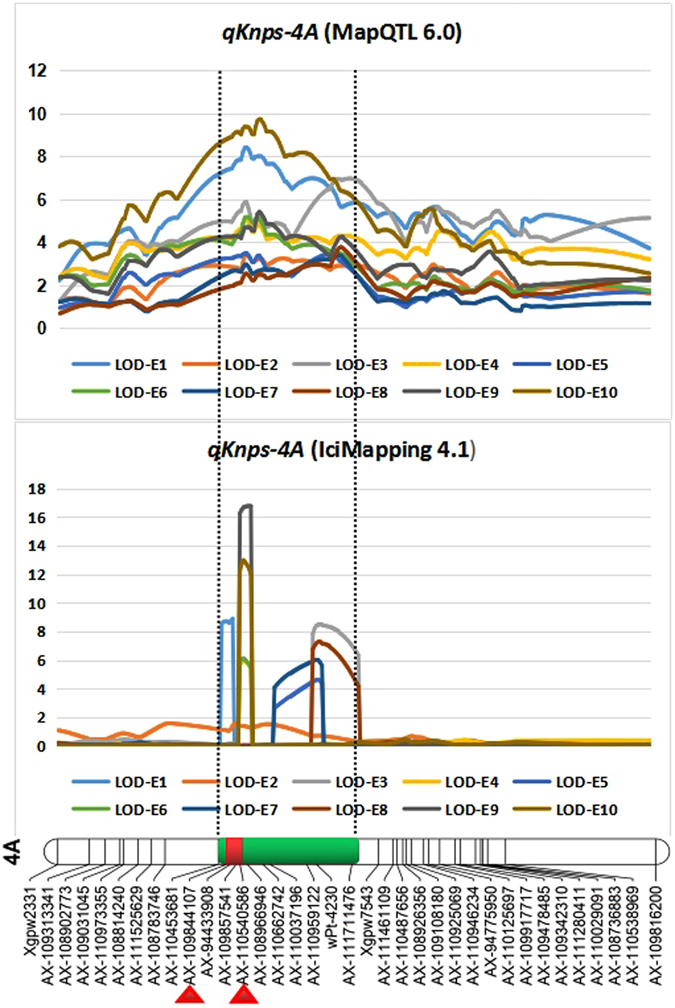

QTLs for KNPS and the prediction of candidate genes

Using the mapping resource along with the phenotypic data we identified important QTLs for yield-related trait. A major stable QTL for kernel number per spike (KNPS; qKnps-4A) was verified in 10 environments by using MapQTL 6.0, IciMapping 4.1, and QTLNetwork 2.0 (Table 1; Fig. 4; Figures S5, S6). qKnps-4A contributed to 8.0–21.2% of the KNPS phenotypic variation in the 188 KJ-RILs, with alleles from J411 increasing kernels per spike by 1.2–2.4. The QTL peaks of qKnps-4A were in 149.8–155.0 cM, 149.7–154.5 cM, and 149.8 cM, as detected by MapQTL 6.0, IciMapping 4.1, and QTLNetwork 2.0, respectively, with Ax-109844107–Ax-110540586 in 149.6–150.3 cM in the overlapping confidence intervals. Thus, we predicted that the candidate genes for qKnps-4A might be within the overlapping confidence intervals of 0.7 cM. Based on the genome assembly of T. aestivum cv. CS (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/), the overlapping confidence intervals of Ax-109844107–Ax-110540586 spanned 3.23 Mb (4 A:680398739–4 A:683638403) in physical position (Figure S7). This region harbours 65 predicted genes in wheat (Figure S8), which might include the candidate gene for qKnps-4A.

Table 1.

qKnps-4A as detected by MapQTL 6.0, IciMapping 4.1, and QTLNetwork 2.0.

| Software | LOD value | Position (cM) | Additive effect | PVE % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MapQTL 6.0 | 3.4 to 9.7 | 149.8 to 155.0 | −1.5 to −2.4 | 8.0 to 21.2 |

| IciMapping 4.1 | 2.8 to 16.8 | 149.7 to 154.5 | −1.2 to −2.4 | 9.5 to 20.3 |

| QTLNetwork 2.0 | P value: 0.000000 | 149.8 | −1.9 | 10.9 |

Figure 4.

Overlapping confidence intervals of QTLs for kernel number per spike (KNPS) based on MapQTL 6.0, IciMapping 4.1 and QTLNetwork 2.0. The segments in red are the overlapping confidence intervals of qKnps-4A, and the overlapping flanking markers of qKnps-4A are indicated by triangles in red, which were detected by QTLNetwork 2.0 based on the combined 10 environmental phenotypic values.

Discussion

The high-density SNP map developed in the present study first documented the genetic positions of 119 001 SNPs from the Wheat660K SNP array. Based on the SNP flanking sequences, we assigned 118 785 SNPs to 56 904 CSS-assembled contigs (Table S3). The physical positions of the corresponding CSS-assembled contigs could be used to validate genetic position (chromosome and chromosomal arms assignment). As shown in Fig. 2 and Table S3, the physical and genetic positions of these mapped markers were generally in agreement.

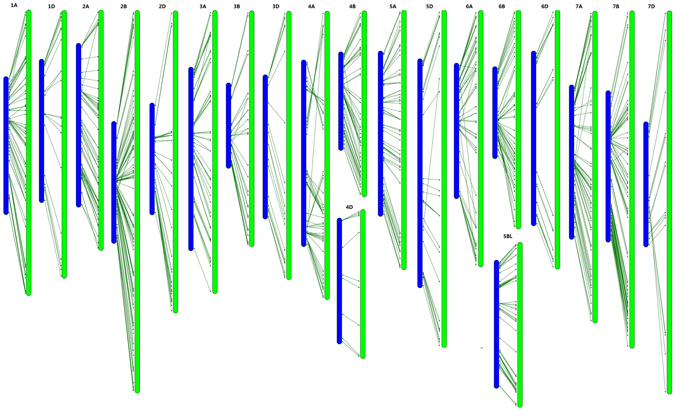

In previous studies, 7504 SNPs from the Wheat9K SNP array12, 46977 SNPs from the Wheat90K array16, and 56505 SNPs from the Wheat820K SNP array18 were genetically mapped to the hexaploid wheat genome. These SNPs have also been physically assigned to the corresponding CSS-assembled contigs. Based on the common CSS contigs, we analysed the synteny of the mapped SNPs (Wheat660K SNP array vs. Wheat90K array and Wheat660K SNP array vs. Wheat820K SNP array) across different mapping populations (Figs 5 and 6). These common contigs were generally aligned with the chromosomes in a consistent order across different mapping populations, verifying the accuracy and credibility of our high-density genetic map. Regarding the total map length, the Wheat90K/820 SNP consensus integrative genetic map is 2.4/1.9 times longer (data not shown) than that of the present map. The increased genetic map length is proportionate to the increased mapping population size16, 18. A relatively small mapping population size resulted in limited identification of recombination events and lower resolution of the genetic map, contributing to the short map length in this study24, 25. In addition, comparative analysis among these three SNP maps revealed that genetic maps of chromosomes 3 A, 4B, 5D, 6D, and 7B derived from the wheat 820 K SNP array were inverted, with long arms at the top and short arms at the bottom (data not shown)18. Chromosome 4 A, derived from the Wheat820K SNP array, might be involved in chromosomal rearrangement compared with the genetic maps derived from the Wheat90K SNP array and our Wheat660K SNP array. The genetic information from the common contigs and their genetic collinearity analysis across different mapping populations will lay the foundation for obtaining a consensus integrative genetic linkage map.

Figure 5.

Synteny of the mapped SNPs from the Wheat660K SNP array (in blue) with that from the Wheat90K array (in red) based on their common CSS-assembled contigs.

Figure 6.

Synteny of the mapped SNPs from the Wheat660K SNP array (in blue) with that from the Wheat820K array (in green) based on their common CSS-assembled contigs. Notes: The genetic maps of chromosomes 3A, 4B, 5D, 6D and 7B derived from the Wheat820K SNP array are shown in inverted form, with long arms at the top and short arms at the bottom18. In this figure, these inversions were corrected.

The SNP order in the present KJ-RIL genetic map was also in good agreement with that in the physical position, with the exception of chromosome 7DL, in which a segment inversion was identified (Fig. 3; Figure S2; Table S3). A previous report showed that wheat chromosome 7 was likely to involve a complex interchange26. These findings prompted us to search for candidate genes of targeted major QTLs. In wheat, a majority of recombination events occurred on the most distal portions of the chromosomal arms, whereas the recombination events tend to be suppressed around the centromere3, 27, 28. These characteristics result in a low resolution of the genetic map in the centromeric region, which was evident in the small genetic distance in the KJ-RIL genetic map corresponding to a large physical region around the centromere compared with the most distal portions of the chromosomal arms (Fig. 3; Figure S2; Table S3). These findings also indicate the difficulty of high-resolution mapping and map-based cloning of a QTL around the centromere because of the low coverage of genetic markers and the suppression of recombination events.

The genetic and genomic research of wheat has lagged behind similar research regarding other important crops, such as rice and maize29. Conservation of gene identity and collinearity among gramineous plants will depend on the rates of genome/gene evolution and rearrangement in the investigated species22. There is a high level of genome-synteny among gramineous plants, especially wheat, Brachypodium and rice, with wheat being more closely related to Brachypodium than to rice22, 23, 30–32. Wheat improvement programs can benefit from the use of comparative genetics to transfer information about genes from model species to wheat, to help identify genes controlling traits of interest, and to assess within-species allelic diversity so that the best alleles can be identified and assembled in superior varieties.

In this study, synteny analyses among common wheat, Brachypodium, rice, sorghum and maize genomes were performed based on the collinearity of the corresponding orthologous genes (best hits of CDSs) (Table S4; Figures S3 and S4). Features of the wheat-grass genome relationships revealed in this study included a high frequency of breakdown in microcollinearity throughout the genomes compared to the previous RFLP-based maps22, 31, 33–36. Both large and especially small synteny blocks across wheat chromosomes and grass family chromosomes were observed in this study. These features might be attributed to the higher number of markers used in this study. More recently, Russo et al.32 conducted collinearity analysis across durum wheat, Brachypodium, and rice based on a high-density durum wheat genetic map derived from the Wheat90K SNP assay. Both large and especially small synteny blocks across wheat chromosomes and grass family chromosomes were also observed in that study. Based on a high-density genetic map, we documented a wheat genome perspective of homologous sorghum and maize genome locations based on comparative sequence analysis. A wheat genome view of homologous gramineous plant genome locations based on comparative sequence analysis would considerably improve the predictability and efficiency of information transfer, and would be benefit evolutionary studies.

Wheat yield is determined by three yield components: productive spikes per unit area, KNPS, and kernel weight, determine wheat yield. Among them, the KNPS value has steadily increased, indicating a substantial contribution of increased KNPS to increased wheat yield37, 38. Over the past several decades, numerous QTLs (or genes) for wheat kernel number have been documented based on both linkage-mapping and association-mapping analyses4, 38–54. Some of these studies have also reported QTLs for KNPS on chromosome 4 A4, 40, 44, 50, 51, 53, 54. Based on genetic marker sequence flanking for these QTLs and the recently released WGS assembly, we compared physical positions with qKnps-4A to determine whether they were common interacting QTLs or regions across genetic backgrounds. The results are shown in Supplementary Table S6. qKnps-4A from our previous research shared a confidence interval (4 A:664209916–4 A:736771450) with qKnps-4A in this study (4 A:680398739–4 A:683638403). Interestingly, qKnps-4A has been detected in both the WY and WJ populations (two related RIL populations sharing one common parental line of Weimai 8)4. QKNS.caas-4AL detected by Gao et al.54, also shared a confidence interval (4 A:632 864 778–4 A:688 093 018) with qKnps-4A in our study. These coincidences confirmed the authenticity of qKnps-4A, which should be subjected to fine mapping and map-based cloning in the future. In fact, this work is being conducted based on the secondary mapping population of qKnps-4A’s (data not shown).

QTL mapping based on the primary mapping population could precisely characterize and locate genes underlying specific agronomic traits, which was also true for both major and moderate/minor QTLs55. Previous studies have confirmed that tagged or cloned genes were near their original QTL positions (logarithm of the odds (LOD) peak)56–67. In this study, qKnps-4A was repeatedly identified using MapQTL 6.0, IciMapping 4.1, and QTLNetwork 2.0, based on mathematical models of composite interval mapping (CIM), inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) and the mixed linear model approach (MLMA), respectively. In addition, the KNPS values of the 188 KJ-RILs and their parental lines were evaluated in 10 different environments. Based on the 10 environmental phenotypic values along with our high-density genetic map, we confirmed QTL peak position with the aforementioned QTL mapping software and found the Ax-109844107–Ax-110540586 overlapping confidence interval, which spanned 3.23 Mb (4 A:680 398 739–4 A:683 638 403) in physical position (Table 1; Fig. 4; Figures S5, S6, S7). In addition, qKnps-4A has been mapped to 4 A:664 209 916–4 A:736 771 450 in both the WY and WJ populations4 and to 4 A:632 864 778–4 A:688 093 018 in the Zhou 8425B/Chinese Spring population54 (Supplementary Table 7). These coincidences across different genetic backgrounds, multiple environments and diverse QTL models strongly supported the hypothesis that the genes underlying qKnps-4A are likely located within 4 A:680398739–4 A:683638403. One of the 65 predicated genes within this interval might be the candidate gene for qKnps-4A (Figure S8). This information is very valuable for future high-resolution mapping and map-based cloning of qKnps-4A.

Using Ax-110540586 as a probe, the 188 KJ-RILs were divided into two groups, one group with alleles from KN9204 and the other with alleles from J411, to perform mean comparisons regarding KNPS. The positive alleles from qKnps-4A’s increased the KNPS value from 3.0 to 4.6, indicating a tremendous potential for their application in wheat molecular breeding programmes designed to increase yield (Figure S9). To characterize the use of qKnps-4A’s positive alleles in wheat breeding programmes, we dissected the genotypes of 65 KN9204-derived advanced lines/authorized varieties, three parental lines of KN9204, three control varieties from the Winter Wheat Performance Trial of the Northern Huang-Huai Regional Nursery of China, and CS near Ax-109844107–Ax-110540586 (Figure S10). None of KN9204′s three parental lines carried favourable alleles for increasing KNPS, which accounted for the negative alleles of KN9204 at this QTL. Only 3 (4.6%) of the 65 authorized/advanced lines derived from KN9204 lines carried favourable alleles for increasing KNPS. Interestingly, two advanced lines (KN1002-13-10 and O-97) carried heterozygous alleles, which were used to develop the secondary mapping population of Knps-4A via self-cross (data not shown). Of the three control varieties from the Winter Wheat Performance Trial of the Northern Huang-Huai Regional Nursery of China, S4185 carried negative alleles, decreasing KNPS; chromosomal regions of Knps-4A in LX99 and JM22 were recombinant regions with alleles that cannot be categorized as favourable or negative alleles that increase or decrease KNPS; and CS carried favourable alleles, increasing KNPS. These findings indicated that favourable qKnps-4A alleles have not been fully utilized in wheat breeding programmes in the Huang-Huai winter wheat region in China. Wheat breeders should strengthen the selection of qKnps-4A favourable alleles in molecular breeding programmes aimed at the development of high-yield varieties.

In summary, this paper reports a high-density wheat genetic map based on an individual mapping population. In total, 119 001 SNP markers derived from the Wheat660K SNP array were mapped onto the KJ-RIL genetic map. We observed good good collinearity of our high-density genetic map with the Wheat90K and Wheat820K consensus genetic maps, increasing the possibility of obtaining a consensus integrative higher-density wheat genetic map in the future. This high-density genetic map is also in good accordance with the recently released wheat genome assembly. Our high-density wheat genetic map provides a major resource for future wheat genetic and genomic research. Moreover, this paper provides an overview of the structural relationships between wheat and other gramineous plant genomes based on comparative genomics analysis. Finally, a major stable QTL for kernel number was thoroughly characterized based on this high-density genetic map and comparative genomics analysis.

Experimental procedures

Plant material

In this study, F8:9 KJ-RILs derived from a cross between KN9204 and J411 were used for map construction and QTL analysis. The original KJ-RIL population contained 427 RILs. In total, 188 randomly sampled lines from the 427 KJ-RILs were used for genetic linkage analysis. In addition, 65 KN9204-derived advanced lines/authorized varieties, three parental lines of KN9204, three control varieties from the Winter Wheat Performance Trial of the Northern Huang-Huai Regional Nursery of China, and CS (Table S7) were genotyped to trace the key chromosomal segment harbouring the major stable QTL for kernel number per spike (KNPS).

Phenotyping

KNPS values of the 188 KJ-RILs and their parental lines were evaluated in ten different environments (five trials that included both low- and high-nitrogen treatments). The nitrogen treatments, field arrangements and experimental designs of the ten environments were performed as described previously3, 68, 69.

Genotyping

For all subjects, leaf tissues were sampled. Genomic DNA was extracted and hybridized on the Wheat660K SNP genotyping array by Compass Biotechnology Company (Beijing, China). The DNA samples were prepared, and the chip genotyping was performed on the Wheat660K SNP array according to the Affymetrix Axiom 2.0 Assay Manual Workflow protocol. DNA integrity was confirmed on agarose gels, and DNA quantity was measured spectrophotometrically. The Wheat660K chip contains 630517 markers (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG2/index.shtml). Variant quality from the Wheat660K chip genotyping was initially assessed according to Affymetrix best practices. The 188 RILs and their parents were aslo assayed using the ‘Wheat PstI (TaqI) 2.3D’ DArT array (the medium density array) (http://www.triticarte.com.au/). The PCR-based markers were genotyped as described in our previous study3.

Genetic map construction

The 188 KJ-RILs and their parental lines were genotyped with the Wheat660K SNP array. SNPs were rejected if they showed minor allele frequency (defined as frequency <0.3) or contained >10% missing data. Markers were binned based on their segregation patterns in the KJ-RIL population using the BIN function in IciMapping 4.1 (http://www.isbreeding.net/) according to Winfield et al.18. Markers that shared their segregation pattern with at least one other marker were retained. One marker was chosen to represent each bin on the basis of the least amount of missing data or, when the percentage of missing data was equal, at random. Markers were tested for significant segregation distortion using a chi-square test. SNPs were sorted into groups using the MAP function in IciMapping 4.1, with the previously mapped 591 loci serving as anchored markers3. A logarithm of the odds (LOD) score of 3.5 and a recombination fraction of 0.3 were used to sort the SNPs with the Kosambi mapping function70. Groups were ordered with the Kosambi mapping function within the JoinMap v. 4.0, using a LOD score ≥3 after preliminary analysis of SNPs with LOD scores ranging from 2 to 10. The long and short arms of each chromosome were identified from the IWGSC wheat survey sequence (http://www.wheatgenome.org/), and groups were orientated to have the short arm above the long arm. MapChart 2.2 (http://www.biometris.nl/uk/Software/MapChart/) was used to draw the genetic map.

QTL mapping analysis

The QTLs for KNPS were identified using MapQTL 6.0 (based on CIM, https://www.kyazma.nl/index.php/mc.MapQTL/), IciMapping 4.1 (based on ICIM, http://www.isbreeding.net/software/?type=detail&id=18), and QTLNetwork 2.0 (based on MLMA, http://ibi.zju.edu.cn/software/qtlnetwork/). For MapQTL 6.0 and IciMapping 4.1, the average KNPS values of each KJ-RIL in each environment were used for individual environment QTL mapping analysis. For QTLNetwork 2.0, the KNPS values of each KJ-RIL in each replication of the 10 environments were assembled to perform combined QTL analysis across environments to identify QTLs with additive-by-environment (A by E) interaction effects. The overlapping confidence intervals detected with the abovementioned programs were used to predict the candidate genes based on the sequence information of the flanking markers and the IWGSC WGA v0.4 assembly of chromosome 4A (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/).

Comparative genomic analysis

The SNP flanking sequences mapped in the KJ-RIL map were kindly provided by Professor Jia JZ. We used the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/executables/release/) to align the SNP probes to the IWGSC survey sequences (contigs). All IWGSC survey sequences were downloaded from http://www.wheatgenome.org/. In addition, contig sequences to which the SNPs were best hits were screened in a BLASTN search against the coding sequences (CDSs) of B. distachyon, rice (O. sativa L.), maize (Z. mays L.), and sorghum (S. vulgare L.). All CDSs were downloaded from http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html. An expectation value (E) of 1E−10 was used as the significance threshold. Synteny analyses with common wheat, Brachypodium, rice, maize and sorghum genomes were performed based on the SNP orders in the KJ genetic map and on the corresponding CDSs in the genome sequences of Brachypodium, rice, maize and sorghum genomes.

Using the sequences of the markers (including SNPs, PCR-based markers and DArTs), we conducted comparative genomics analysis against the contigs assembled in the chromosome survey sequencing (CSS) project. All of the contig sequences were downloaded from https://wheat-urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Seq-Repository. More recently, the genome assembly of T. aestivum cv. Chinese Spring (CS) has been released (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/download/iwgsc/IWGSC-WGA_Sequences/). Based on SNP flanking sequences, we assigned SNPs to this wheat genome assembly.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Compass Biotechnology Company (Beijing, China) for their generous assistance and technical support. We also thank Miss Liu Shuai for her valuable and thoughtful service. This research has been jointly supported by the following grants: the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101802), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471573), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08030107), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association (2016095), the Hebei Provincial Science and Technology Research and Development Project (16226320D) and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-03-01B).

Author Contributions

J.L., G.Z. and J.J. proposed the method and supervised the project. F.C., N.Z. and X.F. performed genotypic identification and data analysis. W.Z., C.Z., L.Y., R.P., M.C., J.H., X.Z., and J.J. conducted the phenotypic evaluation. F.C., N.Z. and X.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Fa Cui, Na Zhang and Xiao-li Fan contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04028-6

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wei Zhang, Email: edithor@126.com.

Guang-yao Zhao, Email: zhaoguangyao@caas.cn.

Jun-ming Li, Email: ljm@sjziam.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Jia J, et al. Aegilops tauschii draft genome sequence reveals a gene repertoire for wheat adaptation. Nature. 2013;496:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling HQ, et al. Draft genome of the wheat A-genome progenitor Triticum urartu. Nature. 2013;496:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui F, et al. A novel genetic map of wheat: utility for mapping QTL for yield under different nitrogen treatments. BMC Genet. 2014;15:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-15-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui F, et al. Construction of an integrative linkage map and QTL mapping of grain yield-related traits using three related wheat RIL populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014;127:659–675. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson JC, et al. Molecular mapping of wheat: major genes and rearrangements in homoeologous groups 4, 5, and 7. Genetics. 1995;141:721–731. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson JC, et al. Molecular mapping of wheat homoeologous group 3. Genome. 1995;38:525–533. doi: 10.1139/g95-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semagn K, et al. Distribution of DArT, AFLP, and SSR markers in a genetic linkage map of a doubled-haploid hexaploid wheat population. Genome. 2006;49:545–555. doi: 10.1139/G06-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Röder MS, et al. A microsatellite map of wheat. Genetics. 1998;149:2007–2023. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.4.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sourdille P, et al. An update of the Courtot × Chinese Spring intervarietal molecular marker linkage map for the QTL detection of agronomic traits in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2003;106:530–538. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akbari M, et al. Diversity arrays technology (DArT) for high-throughput profiling of the hexaploid wheat genome. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;113:1409–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peleg Z, et al. High-density genetic map of durum wheat × wild emmer wheat based on SSR and DArT markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008;117:103–115. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0756-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh CR, et al. Genome-wide comparative diversity uncovers multiple targets of selection for improvement in hexaploid wheat landraces and cultivars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:8057–8062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217133110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkman PJ, Lai K, Lorenc MT, Edwards D. Next-generation sequencing applications for wheat crop improvement. Am. J. Bot. 2012;99:365–371. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai K, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism discovery from wheat next-generation sequence data. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012;10:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo MC, et al. A 4-gigabase physical map unlocks the structure and evolution of the complex genome of Aegilops tauschii, the wheat D-genome progenitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7940–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219082110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:787–796. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maccaferri M, et al. A high-density, SNP-based consensus map of tetraploid wheat as a bridge to integrate durum and bread wheat genomics and breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:648–663. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winfield MO, et al. High-density SNP genotyping array for hexaploid wheat and its secondary and tertiary gene pool. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016;14:1195–1206. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uauy C, Distelfeld A, Fahima T, Blechl A, Dubcovsky JA. NAC Gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science. 2006;314:1298–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1133649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu D, et al. A kinase-START gene confers temperature-dependent resistance to wheat stripe rust. Science. 2009;323:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1166289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, et al. Comparative genetic mapping and genomic region collinearity analysis of the powdery mildew resistance gene Pm41. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014;127:1741–1751. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorrells ME, et al. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of wheat and rice genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:1818–1827. doi: 10.1101/gr.1113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quraishi UM, et al. Cross-genome map based dissection of a nitrogen use efficiency ortho-metaQTL in bread wheat unravels concerted cereal genome evolution. Plant J. 2011;65:745–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferreira A, Silva MF, Silva LC, Cruz CD. Estimating the effects of population size and type on the accuracy of genetic maps. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2006;29:187–192. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572006000100033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poland JA, Brown PJ, Sorrells ME, Jannink JL. Development of high-density genetic maps for barley and wheat using a novel two-enzyme genotyping-by-sequencing approach. PLoS One. 2012;7:32253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naranjo T, Roca A, Goicoechea PG, Giraldez R. Arm homology of wheat and rye chromosomes. Genome. 1987;29:873–882. doi: 10.1139/g87-149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sourdille P, et al. Microsatellite-based deletion bin system for the establishment of genetic-physical map relationships in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Funct. Integr. Genomics. 2004;4:12–25. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torada A, Koike M, Mochida K, Ogihara Y. SSR-based linkage map with new markers using an intraspecific population of common wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;112:1042–1051. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paux E, et al. A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2008;322:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1161847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huo N, et al. Structural characterization of Brachypodium genome and its syntenic relationship with rice and wheat. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:47–61. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9456-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bossolini E, Wicker T, Knobel PA, Keller B. Comparison of orthologous loci from small grass genomes Brachypodium and rice: implications for wheat genomics and grass genome annotation. Plant J. 2007;49:704–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russo MA, et al. A dense durum wheat × T. dicoccum linkage map based on SNP markers for the study of seed morphology. Mol. Breeding. 2014;34:1579–1597. doi: 10.1007/s11032-014-0181-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn S, Anderson JA, Sorrells ME, Tanksley SD. Homoeologous relationships of rice, wheat and maize chromosomes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1993;241:483–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00279889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurata N, et al. Conservation of genomic structure between rice and wheat. Bio. Technol. 1994;12:276–278. doi: 10.1038/nbt0394-276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Deynze AE, et al. Molecular-genetic maps for group 1 chromosomes of Triticeae species and their relation to chromosomes in rice and oat. Genome. 1995;38:45–59. doi: 10.1139/g95-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Deynze AE, et al. Comparative mapping in grasses. Wheat relationships. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995;248:744–754. doi: 10.1007/BF02191715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta PK, Rustgi S, Kumar N. Genetic and molecular basis of grain size and grain number and its relevance to grain productivity in higher plants. Genome. 2006;49:565–571. doi: 10.1139/G06-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Hao C, Wang L, Zhang X. Identifying loci influencing grain number by microsatellite screening in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Planta. 2012;236:1507–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1708-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato K, Miura H, Sawada S. Mapping QTLs controlling grain yield and its components on chromosome 5A of wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;101:1114–1121. doi: 10.1007/s001220051587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Börner A, et al. Mapping of quantitative trait loci determining agronomic important characters in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002;105:921–936. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0994-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang XQ, Kempf H, Ganal MW, Roder MS. Advanced backcross QTL analysis in progenies derived from a cross between a German elite winter wheat variety and a synthetic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004;109:933–943. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marza F, Bai GH, Carver BF, Zhou WC. Quantitative trait loci for yield and related traits in the wheat population Ning7840 × Clark. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;112:688–698. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narasimhamoorthy B, Gill BS, Fritz AK, Nelson JC, Brown-Guedira GL. Advanced backcross QTL analysis of a hard winter wheat × synthetic wheat population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;112:787–796. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirigwi FM, et al. Markers associated with a QTL for grain yield in wheat under drought. Mol. Breeding. 2007;20:401–413. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9100-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar N, Kulwal PL, Balyan HS, Gupta PK. QTL mapping for yield and yield contributing traits in two mapping populations of bread wheat. Mol. Breeding. 2007;19:163–177. doi: 10.1007/s11032-006-9056-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cuthbert JL, Somers DJ, Brule-Babel AL, Brown PD, Crow GH. Molecular mapping of quantitative trait loci for yield and yield components in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008;117:595–608. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang RX, et al. QTL mapping for grain filling rate and yield-related traits in RILs of the Chinese winter wheat population Heshangmai × Yu8679. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;118:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0901-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McIntyre CL, et al. Molecular detection of genomic regions associated with grain yield and yield-related components in an elite bread wheat cross evaluated under irrigated and rainfed conditions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010;120:527–541. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng BS, et al. Using probe genotypes to dissect QTL × environment interactions for grain yield components in winter wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010;121:1501–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang YL, et al. Identification of QTL for yield-related traits in the recombinant inbred line population derived from the cross between a synthetic hexaploid wheat- derived variety Chuanmai 42 and a Chinese elite variety Chuannong 16. Agric. Sci. China. 2011;10:1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(11)60165-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, et al. QTL mapping of yield-related traits in the wheat germplasm 3228. Euphytica. 2011;177:277–292. doi: 10.1007/s10681-010-0267-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett D, et al. Detection of two major grain yield QTL in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under heat, drought and high yield potential environments. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012;125:1473–1485. doi: 10.1007/s00122-012-1927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patil RM, et al. Mapping of QTL for agronomic traits and kernel characters in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Euphytica. 2013;190:117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0785-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao FM, et al. Genome-wide linkage mapping of QTL for yield components, plant height and yield-related physiological traits in the Chinese wheat cross Zhou 8425B/Chinese Spring. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1099. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Price AH. Believe it or not, QTLs are accurate! Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:213–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doebley J, Stec A. Inheritance of the morphological differences between maize and teosinte: comparison of results for two F2 populations. Genetics. 1993;134:559–570. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doebley J, Stec A, Hubbard L. The evolution of apical dominance in maize. Nature. 1997;386:485–488. doi: 10.1038/386485a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alpert KB, Grandillo S, Tanksley SD. fw2.2: a major QTL controlling fruit weight is common to both red- and green-fruited tomato species. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1995;91:994–1000. doi: 10.1007/BF00223911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frary A, et al. fw2.2: a quantitative trait locus key to the evolution of tomato fruit size. Science. 2000;289:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wissuwa M, Yano M, Ae N. Mapping of QTLs for phosphorus-deficiency tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 1998;97:777–783. doi: 10.1007/s001220050955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wissuwa M, Wegner J, Ae N, Yano M. Substitution mapping of Pup1: a major QTL increasing phosphorus uptake of rice from a phosphorus-deficient soil. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002;105:890–897. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamamoto T, Kuboki Y, Lin SY, Sasaki T, Yano M. Fine mapping of quantitative trait loci Hd-1, Hd-2 and Hd-3, controlling heading date of rice, as single Mendelian factors. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1998;97:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s001220050864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El-Din El-Assal S, Alonso-Blanco C, Peeters AJ, Raz V, Koornneef M. A QTL for flowering time in Arabidopsis reveals a novel allele of CRY2. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:435–440. doi: 10.1038/ng767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, Van Eck J, Cong B, Tanksley SD. A new class of regulatory genes underlying the cause of pear-shaped tomato fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13302–13306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162485999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menendez CM, et al. Cold sweetening in diploid potato: mapping quantitative trait loci and candidate genes. Genetics. 2002;162:1423–1434. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin HX, Liang ZW, Sasaki T, Yano M. Fine mapping and characterization of quantitative trait loci Hd4 and Hd5 controlling heading date in rice. Breed. Sci. 2003;53:51–59. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.53.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Werner JD, et al. Quantitative trait locus mapping and DNA array hybridization identify an FLM deletion as a cause for natural flowering-time variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2460–2465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409474102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fan X, et al. QTL for flag leaf size and their influence on yield-related traits in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Mol. Breeding. 2015;35:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0202-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui F, et al. QTL detection for wheat kernel size and quality and the responses of these traits to low nitrogen stress. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016;129:469–484. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosambi DD. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 1944;12:172–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1943.tb02321.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.