Abstract

By linking data from a 40-year birth cohort study with multiple administrative databases, Caspi and colleagues show that 20% of the population accounts for 60% – 80% of several adult social ills. Outcomes for this group can be accurately predicted from as early as age 3, using a small set of indicators of disadvantage. This finding supports policies that target children from disadvantaged families and complements recent literature on the life-cycle benefits of early childhood programmes.

In the past 10 years or so, there has been growing public support for early childhood programs. The most effective programs target children from disadvantaged families1. Despite this evidence, many politicians and thought leaders continue to promote universal programs, primarily on political grounds2.

A new study by Caspi et al.3 contributes substantially to the body of evidence supporting targeted early childhood programs by analyzing rich longitudinal data from a large and representative sample of New Zealand children. The authors follow subjects over their lives from birth through age 384 and enrich their primary sample with matched individual records from a variety of administrative data sources. They report that 20% of the sample accounts for 60–80% of a variety of adult social ills manifest by sample members. A small set of childhood indicators of disadvantage (low IQ; low self-control; childhood maltreatment; and low family socioeconomic status) are powerful predictors of multiple lifetime problem behaviours related to health, crime, education, earnings, and social engagement.

This study advances well beyond the approach typically used in studies of child development. The standard approach predicts one outcome at a time using measures of family disadvantage. Instead, the authors predict constellations, or aggregates, of behaviours, and show that a short list of indicators of disadvantage is powerfully predictive of who exhibits the clusters of adverse outcomes constituting their aggregates. There are many possible measures and clusters of measures of adverse adult outcomes that might be included in their aggregates. However, the authors show that their compelling results do not rely on the choice of any particular measure. There is a “hardcore” group of disadvantaged children who contribute to many social ills when they are adults even when aggregates are formed in different ways.

Their analysis identifies a group of individuals for whom interventions might be effective. It suggests a source of major social problems.

The emphasis of this paper is, however, on predicting adverse adult outcomes. Evidence that childhood adversity predicts adult adversity is an important building block for shaping an effective policy intervention. But the paper stops short of providing any evidence on which, if any, interventions might be effective in preventing the adverse adult behaviours grouped in their clusters. It does not inform us of whether their empirical relationships are due to genes or environments nor does it conduct any mediation analyses to unpack the channels of environmental influences that produce adult adverse outcomes.

Fortunately, there is a companion body of literature consistent with the evidence in this paper that provides guidance on the effectiveness of early childhood interventions and their channels of influence. Several early childhood interventions in the U.S. evaluated by the method of random assignment have followed disadvantaged children up to ages 30–40, the same range of ages reported in this paper. The interventions give enriched early childhood environments to disadvantaged children. Their findings are relevant today because they are based on basic principles of child enrichment widely implemented in a variety of new and ongoing programs.

The economists studying these interventions use benefit/cost and rate of return analyses to place diverse outcomes on a common and interpretable footing of a money metric. Doing so produces policy- relevant aggregates. If a social program provides benefits above the market opportunity cost of funds, it is socially efficient to invest in that program.

The targeted populations enrolled disadvantaged children very comparable to those in the Dunedin New Zealand sample analyzed by the authors. Multiple adult outcomes are measured that are comparable to the ones used in this paper, including health, healthy behaviors, crime and smoking.

For example, the HighScope/Perry Preschool Program targeted disadvantaged 3–4 year-old children5. An analysis of this program by Heckman et al. reports an overall benefit/cost ratio of 7 to 1 with a rate of return of 7–10% per annum6. (The rate of return is the rate at which a dollar investment increases in value each year after the program is implemented.) These benefits account for the welfare cost of using public revenue to finance their costs counting various forms of tax avoidance.

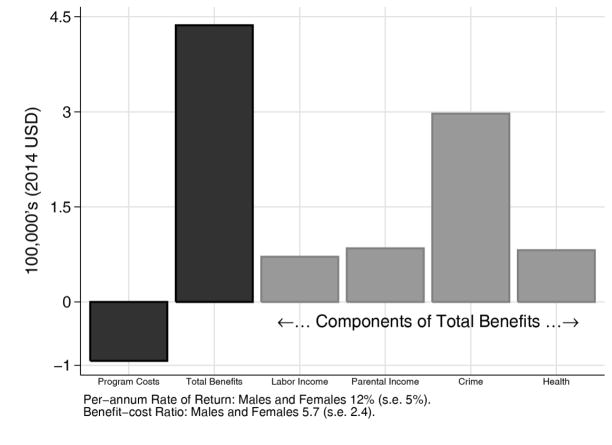

The Carolina Abecedarian Project (ABC) started earlier (age eight weeks) and lasted until age five. Follow-up continued through the mid-30s7. A recent study by Garcia et al. reports a benefit/cost ratio of 6 to 1 with a rate of return of 12% a year, again counting any distortions caused by public funding8. Figure 1 from Garcia et al. shows the total value of the monetized benefits and their components across major life domains.

Figure 1.

Net Present Value of Main Components of the Life-Cycle Benefit/Cost Analysis, Carolina Abecedarian Project

Note: Program costs: the total cost of ABC/CARE, including the welfare cost of taxes to finance it. Total net benefits: for all of the components considered. These include labor income: total individual labor income from ages 20 to the retirement of program participants (assumed to be at age 67). Parental income: total parental labor income of the parents of the participants from when the participants were ages 1.5 to 21. This arises from subsidizing childcare. Crime: the total cost of crime (judicial and victimization costs). Health: gain corresponding to better health conditions until predicted death.

Source: Garcia et al.8

Recent papers by Conti et al.9 and Heckman et al.10 show the causal channels through which these effects are obtained. It would be productive to examine the mediators of the Dunedin study to examine the role of family and social influences. The authors are well positioned to do so.

The body of evidence in the cited papers, coupled with new evidence in this paper, all point to the multiple benefits to society of detecting and addressing early the conditions of disadvantaged children. Targeting disadvantaged children is effective social policy.

References

- 1.Elango S, Hojman A, García JL, Heckman JJ. Early Childhood Education. In: Moffitt, Robert, editors. Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States II. University of Chicago Press; 2016. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of the Mayor. Technical report. New York Department of Education; 2014. Ready to launch: New York City’s implementation plan for free, high-quality, full-day universal pre-Kindergarten. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caspi A, et al. Childhood forecasting of a small segment of the population with large economic burden. Nature Human Behaviour. 2016 doi: 10.1038/s41562-016-0005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulton R, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study: Overview of the first 40 years, with an eye to the future. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:679–693. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weikart DP. Longitudinal Results of the Ypsilanti Perry Preschool Project, Volume 1 of Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Educational Research Foundation; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heckman JJ, Moon SH, Pinto R, Savelyev PA, Yavitz AQ. The rate of return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program. Journal of Public Economics. 2010;94:114–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramey CT, McGinness GD, Cross L, Collier AM, Barrie-Blackley S. The Abecedarian approach to social competence: Cognitive and linguistic intervention for disadvantaged preschoolers. In: Borman KM, editor. The Social Life of Children in a Changing Society. Chapter 7. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1982. pp. 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- 8.García JL, Heckman JJ, Leaf DE, Prados MJ. The life-cycle benefits of an influential early childhood program. University of Chicago, Center for the Economics of Human Development; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conti G, Heckman JJ, Pinto R. The Long-Term Health Effects of Early Childhood Interventions. Economic Journal. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12420. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heckman JJ, Pinto R, Savelyev PA. Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. American Economic Review. 2013;103:2052–2086. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]