Abstract

Introduction

Pediatric sports related concussions are a growing public health concern. The factors that determine injury severity and time to recovery following these concussions are poorly understood. Previous studies suggest that initial symptom severity and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are predictors of prolonged recovery (>28 days) following pediatric sports related concussion. Further analysis of baseline patient characteristics may allow for a more accurate prediction of which patients are at risk for delayed recovery following a sports-related concussion.

Methods

A single-center retrospective case-control study was performed involving patients cared for at the multidisciplinary Concussion Clinic at Children’s of Alabama between 2011–2013. Patient demographic data, past medical history, Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) and symptom severity score, injury characteristics, and patient balance assessment were analyzed for each outcome group. The case group included patients whose symptoms persisted beyond 28 days. The control group consisted of patients whose symptoms resolved within 28 days. Odds ratios for nominal candidate predictor variables were calculated. Calculations were performed using JMP statistical software (Version 11.0 SAS Institute, NC).

Results

A total of 294 patients met the inclusion criteria during the study period. There was no significant difference in age between the case and control groups (p = 0.7). Previous history of concussion (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.6), presenting SCAT2 score <80 (OR 6.9 95% CI 3.35–14.1), SCAT2 symptom severity score >20 (OR 8.67 95% CI 2.43–30.8), previously diagnosed ADHD (OR 2.45, 95% CI 1.1–5.5) and female gender (OR 3.20, 95% CI 1.88–5.47) were all associated with a higher risk of post-concussive symptoms lasting more than 28 days. Concussion suffered while playing a non-helmeted sport was also associated with a higher risk of prolonged symptom duration (OR 2.47, 95%CI 1.46–4.15). Loss of consciousness, amnesia, balance abnormalities, and a history of migraines were not associated with prolonged symptoms beyond 28 days.

Conclusion

This case-control study suggests candidate risk factors for predicting prolonged recovery following sports-related concussion. Large prospective cohort studies will be needed to definitively establish these associations and confirm which children are at highest risk of delayed recovery.

Keywords: Concussion, SCAT2, score, pediatric, trauma, recovery, closed, head, injury

Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) results in 16% of children presenting for medical attention prior to the age of 10.1 Pediatric sports related concussions represent 25–50% of all concussions and are a significant public health concern.1,10 A concussion is defined as a “complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by biomechanical forces”.15 Concussions result in a variety of symptoms and may affect a patient physically, cognitively, and emotionally. The post-concussive syndrome is varied and may not be recognized without close observation following mTBI1. A variety of signs can accompany a concussion including headaches, “feeling in a fog”, emotional variability, loss of consciousness/amnesia, behavioral changes such as irritability, cognitive impairment such as slowed reaction times, and/or sleep disturbances.16

Traditionally, the majority of pediatric patients have been presumed to fully recover after a concussion, but long-term neuropsychological impact is poorly understood. The length of the recovery process depends on many factors, including severity of concussion, age, presence of co-morbidities, and a patient’s post-concussive treatment. The majority of pediatric patients who suffer a concussion recover within three weeks, while some suffer symptoms that persist beyond one month.2,6–8,16,17

Legislation has been passed in many states that require physicians to evaluate all patients following a concussion. This study was performed in Alabama beginning after the Sports-Related Concussion Law was passed in June of 2011. A multidisciplinary concussion clinic was created to medically evaluate and clear a large number of patients for return to play. Based on this experience, it is clear that the ability to predict which patients will have prolonged symptoms would be an incredibly useful clinical tool in determining prognosis and guiding therapy (such as physical and psychological rest).18

While factors such as on-field dizziness, visual impairment, and migraines have been associated with longer recovery times following a sport-related concussion11,12, other factors such as amnesia at the time of the injury6,13,14, prior history of concussions5,7, and athlete’s age at the time of the injury4,9,18 have all been postulated as possible factors that could predict longer symptom severity.18 To the best of the authors’ knowledge no case-control study has ever been performed in the pediatric population to objectively evaluate risk factors associated with delayed recovery following a sports-related concussion.

Methods

Study Design

A single-center case-control study of pediatric sports-related concussions was performed. All patients were seen in a multidisciplinary concussion clinic at Children’s of Alabama (COA). Only those children who sustained a concussion after the implementation of an institution-wide multidisciplinary concussion management program with a dedicated sports-concussion clinic were included in this study. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board approved the study (number X110505004).

All the patients included in this study were seen at COA between August 3, 2011 and January 23, 2013. Inclusion criteria required that all the patients present within four weeks of injury and had to have a dated follow-up visit greater than 28 days from time of injury. The SCAT2 assessment was performed at the time of the initial patient encounter. All types of sports-related concussions were included in this study except for those concussions sustained from more severe injury mechanisms such as motor vehicle accidents. Included in the study were those patients with concussions from motor sports such as motocross and scooters/bikes.

Any patient who experienced a head injury, whether it be from sport or non-sport, that resulted in a temporary loss of brain function followed by the onset of signs and symptoms of a concussion were diagnosed with a concussion and were referred to the Sports Concussion Clinic (SCC) for initial evaluation. In this study, the COA emergency room attending physician and/or the SCC attending physician made the diagnosis of concussion according to the definition outlined in the 2008 Zurich International Consensus on Concussion in Sport.15,16

The patients were divided into two groups. The case group consisted of patients with symptoms that persisted beyond 28 days and the control group had symptom resolution within 28 days. Symptom resolution was determined by the patient returning to their pre-concussions state of health with complete resolution of post-concussive symptoms. Patient demographic data, past medical history, Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) and symptom severity scores on presentation, injury characteristics, and patient balance assessment were analyzed for each outcome group. Recovery was defined as patients that were symptom free both at rest and with exertion. The patient, at their last clinical follow-up, defined the timing of symptom resolution.

Statistical Analysis

A case-control study was performed between patients whose symptoms persisted beyond 28 days and those whose symptoms resolved within 28 days. Odds ratio calculations were performed for candidate, nominal predictor variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis (including odds ratio). Chi square test, Fisher’s exact, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were also employed. All analyses for the study was performed with JMP Version 11.0 (SAS Institute, North Carolina).

Results

562 patients suffered a concussion and presented to Children’s of Alabama between August 2011 and January 2013. Sixty-seven patients presented more than 4 weeks after suffering his/her initial concussion and 198 patients failed to follow-up with Children’s of Alabama until symptom resolution was reported. Three additional patients were excluded that were over the age of 18. 294 patients were included in the case-control analysis. The control group consisted of patients whose symptoms resolved within 28 days (n=189, 64%) and the case group included patients whose symptoms failed to resolve within 28 days (n=105, 36%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Control Group-Early Recovery (%) | Case Group-Delayed Recovery (%) | p= | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=189 (0.64) | n = 105 (0.36) | ||

| Age | 13.4 (± 2.75) | 13.1 (±3.0) | 0.7 |

| Male | 155 (0.53) | 62 (0.21) | |

| Female | 34 (0.12) | 43 (0.15) | 0.001 |

| ADHD | 12 (0.04) | 15 (0.05) | 0.02 |

| Migraines | 7 (2.38) | 7 (2.38) | 0.2 |

| Previous Concussion | 37 (0.128) | 35 (0.121) | 0.008 |

| Number of Previous Concussions | 0.27 (±0.65) | 0.51 (±0.94) | 0.01 |

| Total SCAT2 Score* | 85.05 (±8.6) | 72.9 (±10.8) | 0.001 |

| SCAT2 Symptom Severity Score | 8.15 (±12.3) | 33.6 (20.4) | 0.001 |

| Amnesia | 35 (0.118) | 29 (0.09) | 0.08 |

| Loss of Consciousness | 41 (0.139) | 30 (0.101) | 0.25 |

| Balance Problems | 6 (0.02) | 6 (0.02) | 0.30 |

From the Third International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport

The majority of the patients were male (74%, n=217) but female gender was associated with a higher rate of delayed recovery (p=0.001: OR 3.2 95% CI 1.84–5.41) (Table 2). The patients ranged in age from 4 to 18 with a mean of 13.3 years. There was no statistically significant difference between the case and control groups in regards to age (p=0.7). A past medical history of ADHD (OR 2.45 95% CI 1.1–5.5) and concussion (OR 2.1 95% CI 1.2–3.6) were found to be associated with prolonged time to recovery. The total number of previous concussions was also slightly higher in the case group (See Table 1, p=0.01). The case group did not have a significantly higher rate of migraines (p=0.2).

Table 2.

Odds Ratio for Predictor Variables of Delayed Symptom Recovery

| Potential Predictor Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Female Gender | 3.20 | 1.88–5.47 |

| ADHD | 2.45 | 1.1–5.5 |

| Previous history of concussion | 2.1 | 1.2–3.6 |

| Lower presenting total SCAT2 score* | 6.9 | 3.35–14.1 |

| Higher SCAT2 Symptom severity Score** | 8.67 | 2.43–30.8 |

| Non-helmeted Sport | 2.47 | 1.46–4.15 |

Defined as a SCAT2 score less than 80

Defined as SCAT2 symptom severity score >20

A majority of these patients suffered concussions during organized sports such as football, baseball, basketball, soccer, and cheerleading (n=213) (Table 3). Of note, concussions suffered during a non-helmeted sport resulted in a higher risk of delayed recovery (OR 2.47 95%CI 1.46–4.15). Patients experienced loss of consciousness (n=73, p=0.25), amnesia (n=64, p=0.08), and difficulties with balance (p=0.25) following their concussions. These three factors did not have a statistically significant relationship to outcome.

Table 3.

Sport played by patient at the time of the Concussion (N=294)

| Sport | Patients with symptoms for <28 days, n | Patients with symptoms for >28 days, n |

|---|---|---|

| Football | 99 | 26 |

| Basketball | 18 | 13 |

| Soccer | 13 | 4 |

| Cheerleading | 3 | 5 |

| Other sports | 41 | 43 |

| Unspecified sport | 21 | 15 |

| Helmeted Sports | 111 | 41 |

| Non-Helmeted Sports | 56 | 51 |

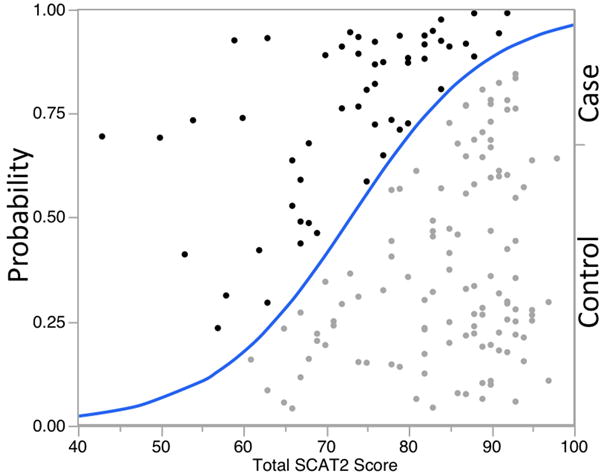

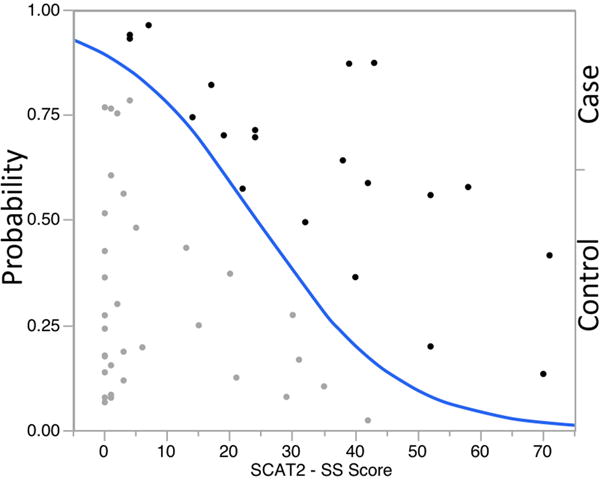

The SCAT2 and SCAT2 symptom severity scores were found to correlate with the case and control group. A SCAT2 score less than 80 (OR 6.9 95% CI 3.35–14.1) and a SCAT2 symptom severity score (SSSS) greater than 20 (OR 8.67 95% CI 2.43–30.8) were associated with the prolonged recovery case group. Univariate logistic regression analysis of the total SCAT2 score and SSSS also demonstrated a statistically significant relationship with post-concussive symptoms lasting more than 28 days (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Probability Curve of Total SCAT2 Score. The curve represents the probability for each SCAT 2 score in both the Case (Solid Dots) and Control groups. For instance, a SCAT 2 score of 80 has a 68% probability of being in the Control group. As the score decrease there is a higher probability of that score being from the Case group. Patients with a lower SCAT 2 score have a higher probability of experiencing symptoms for greater than 28 days.

Figure 2.

Probability Curve of Total SCAT 2 Symptom Severity Score (SSSS). The curve represents the probability for each SSSS in both the Case (Solid Dots) and Control groups. For instance, a SSSS score of 20 has a 60% probability of being in the Control group. As the score increases there is a higher probability of that score being from the Case group. Patients with a higher SSSS have a higher probability of experiencing symptoms for greater than 28 days.

Multivariate analysis was also performed for gender and demonstrated that females had a higher rate of delayed recovery (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression of Female Gender predicting delayed recovery

| Model | Female Gender OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 3.49 | 2.02–6.02 |

| Previous Concussions | 3.6 | 2.08–6.25 |

| ADHD+Prev Concussion | 4.11 | 2.33–7.26 |

| ADHD +_No Helmet | 2.49 | 1.28–4.85 |

| Prev Concussion + No Helmet | 2.64 | 1.34–5.2 |

| ADHD+No Helmet+Prev Concussion | 2.89 | 1.45–5.77 |

Discussion

Concussions are a significant public health concern and many states have passed legislation requiring all children that suffer a sports-related concussion to be evaluated by a physician. The physician is then required to medically clear the patient for return to play. Sports-related concussion is thus a unique medical entity in that the physician is required by law to provide prognostic information and take steps to medically clear the patient. The Alabama Sports-Related Concussion Law of 2011 led to the development of the multidisciplinary concussion clinic at COA that was tasked with clearing patients for return to play over a large urban and rural area. To our knowledge no case-control study has been performed to allow clinicians to make key diagnostic and prognostic decisions in pediatric sports-related concussions.

The present study demonstrated that female gender, previous history of concussion(s), previously diagnosed ADHD, a lower initial total SCAT2 score, a higher presenting SSSS, and participation in a non-helmeted sport were all associated with a higher risk of post-concussive symptoms lasting more than 28 days. Meanwhile, other selected predictors such as loss of consciousness, balance difficulties, and amnesia were not associated with prolonged symptoms after concussion. These findings provide useful prognostic information for patients, their parents, coaches, and athletic trainers. Additionally, these findings may result in a change in physician expectation regarding the speed at which a player may be allowed to return to play. The current recommendations require a graduated return-to-play protocol and require a minimum of one week for return to play. Prospective study of these patient groups may demonstrate that certain individuals benefit from prolonged cognitive and physical rest, potentially improving long-term outcomes.

The study was designed to provide clinicians with predictors that could be used to determine if a concussed individual is likely to suffer from prolonged post-concussive symptoms. The only modifiable variable analyzed in this study was use of a helmet. We found that concussions suffered in a helmeted sport had a shorter duration than those suffered in a non-helmeted sport. Whether this actually represents decreased severity of concussion or merely reflects reporting bias (i.e. are football players more likely to deny symptoms and return to play early) is unclear, but merits further study.

There have been multiple studies looking at the relationship between age and recovery that have reported a longer mean recovery time post-concussion in younger athletes than in older athletes.3,4,19 Our study was performed at a pediatric hospital with an average age of 13 years. Age within this pediatric population was not found to be associated with a delayed recovery. While some studies have suggested that amnesia can possibly predict a concussed individual suffering from post-concussive longer than 28 days, our study reinforced another study’s finding that amnesia is not associated with prolonged symptom duration.4,6,19

The present study has certain limitations that require further prospective study. The study was performed retrospectively, and initial documentation was reliant on patient and family recall. Additionally, not all patients underwent SCAT2 and SSSS testing. A potential limitation in this study is that most participants were seen in a multidisciplinary clinic and these findings may not be generalizable to other outpatient settings. An additional concern, in a state like Alabama, where participation in sports, particularly football, is associated with significant social pressure, is that patients may not be entirely honest, as complaints will preclude them from returning to play.

This study provides more evidence that large prospective cohort studies are needed to definitively establish associations between clinical predictors and prolonged symptom severity; these studies in turn will be used to develop clinical prediction models to further assist clinicians in the management of individuals who suffer from concussions. The 5P (Predicting Persistent Postconcussive Problems in Pediatrics) study has not starting enrolling patients at the time of this writing but is designed to help answer some of these very difficult questions (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT01873287).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Barlow KM, Crawford S, Stevenson A, Sandhu SS, Belanger F, Dewey D. Epidemiology of postconcussion syndrome in pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e374–381. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancelliere C, Hincapié CA, Keightley M, Godbolt AK, Côté P, Kristman VL, et al. Systematic Review of Prognosis and Return to Play After Sport Concussion: Results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:S210–S229. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins M, Lovell MR, Iverson GL, Ide T, Maroon J. Examining concussion rates and return to play in high school football players wearing newer helmet technology: a three-year prospective cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:275–286. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000200441.92742.46. discussion 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field M, Collins MW, Lovell MR, Maroon J. Does age play a role in recovery from sports-related concussion? A comparison of high school and collegiate athletes. J Pediatr. 2003;142:546–553. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gronwall D, Wrightson P. Cumulative effect of concussion. Lancet. 1975;2:995–997. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)90288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guskiewicz KM, McCrea M, Marshall SW, Cantu RC, Randolph C, Barr W, et al. Cumulative effects associated with recurrent concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2549–2555. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guskiewicz KM, Ross SE, Marshall SW. Postural Stability and Neuropsychological Deficits After Concussion in Collegiate Athletes. J Athl Train. 2001;36:263–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iverson GL, Brooks BL, Collins MW, Lovell MR. Tracking neuropsychological recovery following concussion in sport. Brain Inj BI. 2006;20:245–252. doi: 10.1080/02699050500487910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson EW, Kegel NE, Collins MW. Neuropsychological assessment of sport-related concussion. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30:73–88. viii–ix. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkwood MW, Yeates KO, Wilson PE. Pediatric sport-related concussion: a review of the clinical management of an oft-neglected population. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1359–1371. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau BC, Kontos AP, Collins MW, Mucha A, Lovell MR. Which on-field signs/symptoms predict protracted recovery from sport-related concussion among high school football players? Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2311–2318. doi: 10.1177/0363546511410655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau B, Lovell MR, Collins MW, Pardini J. Neurocognitive and symptom predictors of recovery in high school athletes. Clin J Sport Med Off J Can Acad Sport Med. 2009;19:216–221. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31819d6edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovell MR, Collins MW, Iverson GL, Field M, Maroon JC, Cantu R, et al. Recovery from mild concussion in high school athletes. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:296–301. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.2.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrea M, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Barr W, Randolph C, Cantu RC, et al. Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:2556–2563. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, Cantu RC, Dvořák J, Echemendia RJ, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Zurich, November 2012. J Athl Train. 2013;48:554–575. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Molloy M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 3rd International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. J Athl Train. 2009;44:434–448. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.4.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meehan WP, 3rd, d’Hemecourt P, Collins CL, Comstock RD. Assessment and management of sport-related concussions in United States high schools. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:2304–2310. doi: 10.1177/0363546511423503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meehan WP, 3rd, Mannix RC, Stracciolini A, Elbin RJ, Collins MW. Symptom severity predicts prolonged recovery after sport-related concussion, but age and amnesia do not. J Pediatr. 2013;163:721–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellman EJ, Lovell MR, Viano DC, Casson IR, Tucker AM. Concussion in professional football: neuropsychological testing–part 6. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1290–1303. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000149244.97560.91. discussion 1303–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]