Abstract

Background

Esophageal carcinoma is the third most common gastrointestinal malignancy worldwide and is largely unresponsive to therapy. African-Americans have an increased risk for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), the subtype that shows marked variation in geographic frequency. The molecular architecture of African-American ESCC is still poorly understood. It is unclear why African-American ESCC is more aggressive and the survival rate in these patients is worse than those of other ethnic groups.

Methods

To begin to define genetic alterations that occur in African-American ESCC we conducted microarray expression profiling in pairs of esophageal squamous cell tumors and matched control tissues.

Results

We found significant dysregulation of genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes and stress response components of the NRF2- mediated oxidative damage pathway, potentially representing key genes in African-American esophageal squamous carcinogenesis. Loss of activity of drug metabolizing enzymes would confer increased sensitivity of esophageal cells to xenobiotics, such as alcohol and tobacco smoke, and may account for the high incidence and aggressiveness of ESCC in this ethnic group. To determine whether certain genes are uniquely altered in African-American ESCC we performed a meta-analysis of ESCC expression profiles in our African-American samples and those of several Asian samples. Down-regulation of TP53 pathway components represented the most common feature in ESCC of all ethnic groups. Importantly, this analysis revealed a potential distinctive molecular underpinning of African-American ESCC, that is, a widespread and prominent involvement of the NRF2 pathway.

Conclusion

Taken together, these findings highlight the remarkable interplay of genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of African-American ESCC.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3423-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: mRNA expression, Microarray, Down-regulated genes, Up-regulated genes, Pathway analysis, Targeted therapy

Background

Esophageal cancer is the third leading gastrointestinal malignancy worldwide with greater incidence in males than in females. Patients with esophageal cancer (EC) show limited response to multimodal treatments with an overall five-year survival rate of only about 20% [1]. Due to lack of effective screening for early detection, EC is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage or when metastasis has already occurred. Consistently reliable molecular markers to monitor outcomes remain to be developed [2].

Esophageal cancer has two main histologic subtypes and they arise in two distinct areas of the esophagus. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (EAC) is mostly seen in Western countries [3] while esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is predominant in Eastern countries and the eastern part of Africa [3]. Geographical and genomic differences play a significant role in ESCC [4]. In African-Americans, ESCC is the predominant subtype, and the survival rate is worse than in patients of other ethnic groups [5].

The combined action of genetic and environmental factors is believed to underlie the etiology of esophageal cancer. Recent genome-wide association studies, gene expression profiling, DNA methylation and proteomic studies conducted in Japanese and Chinese ESCCs (reviewed in [6]) have identified multiple risk variants and gene signatures associated with ESCC. These studies presented additional evidence for the effect of environmental exposures such as alcohol intake, smoking, opium abuse, hot food and beverage consumption, and diet as risk factors for ESCC [3, 7–11].

Genetic and transcriptome analyses on African-American ESCC have been particularly limited which highlights the lack of understanding of the genetic architecture of ESCC in this ethnic group. In an earlier study of black male ESCC samples, we detected loss of heterozygosity that spanned a significant portion of chromosome 18 [12]. To explore the entire anatomy of the neoplastic genome in black ESCC, we performed comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) on a panel of 17 matched pairs of tumor and control esophageal tissues [13]. Multiple chromosomal gains, amplifications and losses that represent regions potentially involved in etiology defined the pattern of abnormalities in the tumor genome [13]. We noted genomic imbalances that were represented disproportionately in African-American ESCC compared to those reported in ESCC of other ethnic groups including Japanese [14–18], South African black and mixed-race individuals [19], Taiwan Chinese [20], Hong Kong Chinese [21], Chinese in Henan province [22], and Swedes [23].

The preponderance of chromosomal aberrations in African-American ESCC predicts concomitant changes in gene activity during carcinogenesis. We sought to identify dysregulated genes and pathways that could define the expression signature in African-American ESCC by conducting microarray expression profiling in paired squamous esophageal tumors and normal tissue specimens. Here, we report significant differential expression of a wide array of genes involved in multiple pathways that may be crucial to causation and/or progression. Particularly noteworthy is the dysregulation of NRF2 mediated oxidative stress genes and genes that encode drug-metabolizing enzymes and xenobiotics that may, in part, contribute to the aggressive nature of ESCC among blacks.

Methods

Samples

Seven paired specimens of the esophagus (tumor and matching non-tumor tissues), each pair derived from the same patient, were collected endoscopically or surgically at the time of diagnosis, frozen and stored at -80 °C until use. Staging indicated that all tumors included in this study were at Stage IV. This study was done under a protocol approved by the Washington D.C. VAMC Institutional Review Board and a written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to biopsy or surgery. The demographics and risk factors of the patients are listed in the Additional file 1.

RNA extraction

Tissue samples were subjected to total RNA extraction using TRIzol-reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The concentration of each RNA sample was determined by NanoDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). RNA quality was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA).

cRNA preparation and expression profiling

An aliquot of 5 μg of high-quality total RNA from each sample was used to synthesize cDNA and biotinylated cRNA utilizing the Affymetrix GeneChip® Expression 3’Amplification One-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagent kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated cRNA was hybridized to Affymetrix Gene-Chips HG U133 Plus 2 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), washed, stained on the Affymetrix Fluidics station 400 and scanned with a Hewlett Packard G2500A Gene Array Scanner following Affymetrix instructions. All arrays used in the study passed the quality control set by Tumor Analysis Best Practices Working Group [24].

Microarray data analysis

The Affymetrix scanner 3000 was used in conjunction with Affymetrix GeneChip Operation Software to generate one. CEL file per hybridized cRNA. These files have been deposited in NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the GEO accession number of GSE77861 and are freely available for download.

The Affymetrix Expression Console was used to summarize the data contained across all .CEL files and generate 54,675 RMA normalized gene fragment expression values per file. Quality of the resulting values was challenged and assured via Tukey box plot, covariance-based PCA scatter plot, and correlation-based heat map using functions supported in “R” (www.cran.r-project.org). Lowess modeling of the data (CV ~ mean expression) was performed to characterize noise for the system and define the low-end expression value at which the linear relationship between CV and mean was grossly lost (expression value = 8). Gene fragments not having at least one sample with an expression value greater than this low-end value were discarded as noise-biased. For gene fragments not discarded, differential expression was tested between Tumor and Non-tumor biopsies via paired t-test under Benjamini–Hochberg multiple comparison correction condition (alpha = 0.05). Gene fragments having a corrected P < 0.05 by this test and an absolute difference of means > = 1.5X were subset as those having differential expression between Tumor and Non-Tumor. Gene annotations for these subset fragments were obtained from IPA (www.ingenuity.com) along with the corresponding enriched functions, enriched pathways, and significant predicted upstream regulators. The analysis pipeline is summarized in the Additional file 2.

Validation of results by real-time PCR

RT-PCR was performed for KRT17, PRDCSH, TNFRSF6B, SELK, RAB5B, ALD, RAF genes. The delta-delta Ct calculation method was used for the quantification of the RT-PCR results.

Pathway analysis

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Qiagen- Build version 364,062 M, Content version 26,127,183) was used to determine perturbed pathways. In addition, we performed IPA to identify perturbed pathways affected in ESCC from different ethnic groups by utilizing publicly available datasets of ESCC mRNA expression microarrays including GSE17351 [25], GSE20347 [26], GSE23400 [27], GSE29001 [28], GSE33426 [28], GSE33810 [29] and GSE45670 [30] from the GEO repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The characteristics of these studies such as sample size, tissue storage, and control tissue type are presented in the Additional file 3. The differentially expressed gene lists were obtained by the analysis with GEO2R (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). The p-values were adjusted with Benjamini and Hochberg correction.

Results

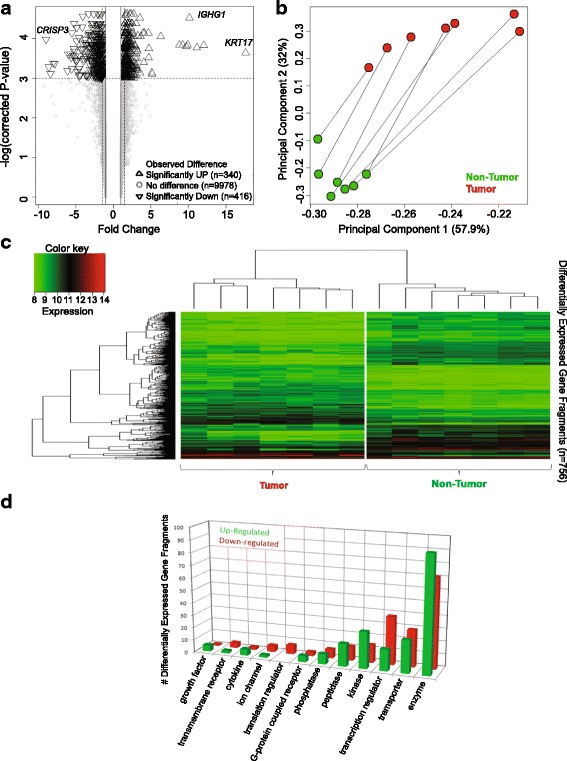

Transcriptome profiling of African-American ESCC tumors versus adjacent normal esophageal tissues revealed significant differential expression of 756 genes comprising 340 over-expressed and 416 under-expressed loci that were detected by 460 and 558 gene probes, respectively (Additional file 4). A volcano plot displayed genes that underwent the highest alteration in expression (Fig. 1a). Among the most strongly up-regulated genes are keratin 17 (KRT17), immunoglobulin genes including IGHG1 and ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1). Genes that showed a huge loss of expression included cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 (CRSP3) and sciellin (SCEL). Experimental validation of microarray results through a real-time PCR assay on RNA derived from the same original samples for selected up-regulated (KRT17, PRDCSH, TNFRSF6B) and down-regulated (SELK, RAB5B, ALD, RAF) genes supported the microarray data (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Gene expression differences observed between paired Esophageal Tumor and Non-Tumor biopsies for seven patients. a Volcano Plot depicting the differential expression testing results for 10,734 gene fragments. Gene fragments having significant difference in expression between Tumor and Non-Tumor where the magnitude of difference is also > = 1.5X are represented as triangles (n = 756). b Covariance-based Principal Component Analysis (PCA) scatter plot depicting the paired sample relationships when the 756 gene fragments identified to have significant difference in expression between Tumor and Non-Tumor are used. c Correlation-based clustered heat map depicting the sample relationships (x-axis) when the 756 gene fragments identified to have significant difference in expression between Tumor and Non-Tumor (y-axis) are used. d Bar plot describing the breakdown of the 756 gene fragments identified to have significant difference in expression between Tumor and Non-Tumor by protein type (where known).

Principal component analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated the magnitude of the co-variance between paired tumor and non-tumor samples of each patient (Fig. 1b). The first principal component contributed 57.9% of the variance among the samples. Correlation-based clustering of all differentially expressed genes distinguished clearly tumor from the corresponding non-tumor tissues (Fig. 1c).

Perturbed pathways and networks in African-American ESCC

To determine the overall biological impact of the widespread transcriptional aberration in African-American ESCC, we performed pathway and network analysis on significantly dysregulated using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). The majority of differentially expressed genes encoded a diversity of enzymes (Fig. 1d). Genes that coded for transporters, transcription regulators, phosphatases, translation regulators, ion channels and transmembrane receptors were among those that were most prominently down-regulated (Fig. 1d).

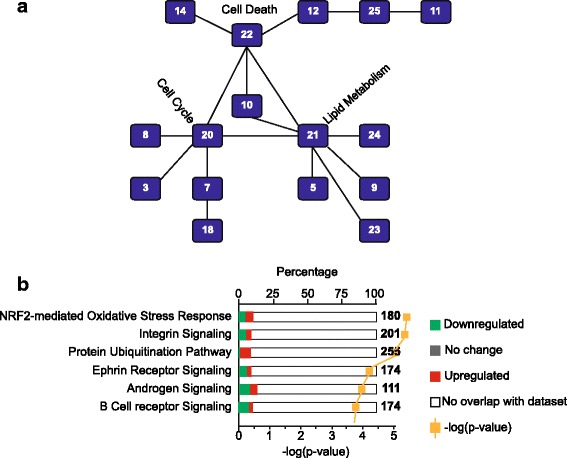

IPA detected the enrichment of 25 networks (Fig. 2, Additional file 5), 14 of which were interconnected. Networks 20, 21, and 22 displayed linkage to at least five other networks representing the highest number of interconnections. The cell cycle and organismal injury and abnormalities were the constituent pathways of network 20. Network 21 included carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and molecular transport, and network 22 comprised cell death and survival pathways. (The complete list of genes in these networks is presented in Additional file 5).

Fig. 2.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) of ESCC. a Interconnected canonical pathways. Pathway 20 (injury and abnormalities and cell cycle), pathway 21 (carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, and molecular transport), and pathway 22 (cell death and survival pathways) serve as hub for interconnected canonical pathways. b The enriched canonical pathways in ESCC by IPA. The most enriched pathways represented the higher –log(p-value). The white bar represents the genes that do not overlap with the data set. Green bar represents genes that are down-regulated and red bar represents genes that are up-regulated. The gray bar demonstrates the genes without any change in expression.

Fifteen canonical pathways were significantly enriched in African-American ESCC and the top three included NRF2-mediated oxidative stress pathway, integrin signaling and protein ubiquitination, in that order (Fig. 2b, Additional file 6). The gene constituents of these pathways are presented in Additional file 7. These results suggest that African-American ESCC is underpinned by a dysregulation of genes that play an important role in oxidative stress and xenobiotic metabolic responses.

Activation of NRF2 perturbs stress response and detoxification pathways in ESCC

Enriched pathways involving stress response, xenobiotic metabolism, and toxic response are noteworthy because smoking and alcohol consumption have been consistently shown to be strong contributing factors in ESCC etiology. It was therefore important to focus on pathways involved in detox networks.

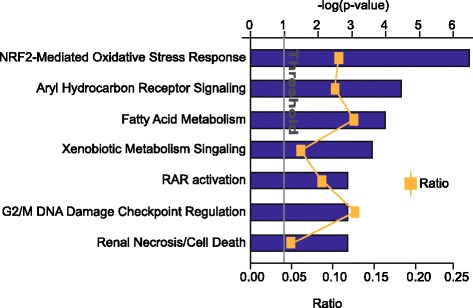

The NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response pathway showed the highest enrichment (with a –log(p) of 6.25), in general, and in the toxicology panel as well (Fig. 3). NRF2 pathway is one of the primary mediators of detoxification and metabolism responses. Transcriptional targets of NRF2 include genes involved in alcohol metabolism such as ADH7, AKR1B1, ALDH3A1, and ALDH7A1, all of which are differentially expressed in our dataset (Additional file 8). Other targets that showed altered expression in African-American ESCC include genes with a wide range of function: MGST2, ABCC1, ABCC5, GCLC GPX4, ACOX1, BLVRA, FTL1, CEBPB, ACLY, ELOVL5, FABP5, ACAA1B.

Fig. 3.

The toxicology chart summarizes the enrichment of detoxification pathways enriched in our dataset by IPA. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) identified NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response pathway as the most enriched toxicology pathway. Blue bar represent –log(p-value) and the ratio is the number of genes characterized in the dataset compared to the total number of genes belonging to that pathway

IPA predicted that 19 upstream regulators are activated in our dataset (Table 1 and Additional file 9). Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 gene, NFE2L2, a known upstream regulator of the NRF2 pathway was predicted to have the highest activation z-score of 3.796, followed by MEK, LDL, and CTNNB1 pathways, with decreasing z-scores. In addition, MYC was predicted to be an activated upstream regulator (Additional file 9).

Table 1.

Comparison of the predicted upstream regulatory pathways in ESCC

| GSE77861 | GSE17351 | GSE33810 | GSE20347 | ||||||||

| Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) |

| NFE2L2 | 3.8 | 7.5 | NUPR1 | 4.7 | 10.1 | mir-8 | 2.6 | 1.2 | RABL6 | 5.8 | 26.7 |

| MEK | 2.7 | 1.2 | CLDN7 | 3.9 | 7.9 | let-7 | 2.6 | 0.3 | FOXM1 | 4.4 | 14.2 |

| LDL | 2.8 | 0.5 | MYOCD | 3.8 | 6.0 | LYN | 2.4 | 0.6 | IgG complex | 3.7 | 21.9 |

| CTNNB1 | 2.6 | 1.6 | NR3C1 | 3.7 | 4.2 | IL10RA | 2.3 | 1.0 | MITF | 3.5 | 15.8 |

| RABL6 | 2.5 | 2.1 | IRGM1 | 3.5 | 7.0 | TRIM24 | 2.4 | 0.1 | FOXO1 | 3.4 | 11.3 |

| FOXM1 | 2.4 | 1.2 | BNIP3L | 3.4 | 8.2 | miR-1-3p | 2.2 | 0.8 | RARA | 3.3 | 16.2 |

| CBX5 | 2.3 | 2.4 | RBL2 | 3.2 | 4.8 | IFI16 | 2.2 | 0.4 | TLR7 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| ANGPT2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | TP53 | 3.2 | 21.1 | ZBTB16 | 2.2 | 2.0 | PRL | 3.3 | 8.1 |

| PLIN5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | IL1RN | 3.1 | 4.3 | miR-10 | 2.2 | 0.4 | IFNL1 | 3.2 | 10.0 |

| ANXA7 | 2.2 | 2.4 | SRF | 3.0 | 5.7 | CDKN2A | 2.1 | 0.1 | TGFB1 | 3.2 | 46.3 |

| TP53 | −3.1 | 18.4 | CSF2 | −5.6 | 9.3 | ERBB2 | −3.2 | 8.2 | TP53 | −5.3 | 38.7 |

| IL13 | −3.0 | 0.7 | RABL6 | −4.1 | 8.9 | SHH | −3.1 | 7.8 | NUPR1 | −4.4 | 19.5 |

| CDKN2A | −3.0 | 2.6 | SPP1 | −4.1 | 5.3 | IGFBP2 | −3.1 | 7.5 | SPDEF | −4.0 | 8.7 |

| CD28 | −2.8 | 2.0 | EGFR | −3.8 | 14.0 | TGFB3 | −2.9 | 7.5 | KDM5B | −3.4 | 12.6 |

| EHF | −2.5 | 2.3 | ERK1/2 | −3.8 | 9.2 | ERG | −2.9 | 7.0 | HSF1 | −3.3 | 6.7 |

| CLDN7 | −2.4 | 3.9 | EGF | −3.7 | 9.9 | CCTNB1 | −2.7 | 7.1 | CDKN1A | −3.3 | 9.5 |

| let-7 | −2.2 | 0.5 | HGF | −3.6 | 17.1 | CREB | −2.6 | 1.7 | CLDN7 | −3.1 | 6.7 |

| ESRRA | −2.2 | 1.4 | TNF | −3.4 | 3.9 | WNT1 | −2.5 | 0.6 | BTK | −2.9 | 5.0 |

| TCF3 | −2.0 | 0 | E2F1 | −3.4 | 7.9 | CCND1 | −2.5 | 2.9 | WISP2 | −2.9 | 8.6 |

| FGFR1 | −2.0 | 0.8 | FN1 | −3.4 | 4.7 | ERG2 | −2.5 | 0.9 | E2F6 | −2.8 | 4.3 |

| GSE29001 | GSE33426 | GSE45670 | GSE23400 | ||||||||

| Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) | Gene | z-score | -log(p) |

| RABL6 | 5.8 | 25.2 | TGFB1 | 7.7 | 42.9 | TNF | 5.3 | 24.0 | CSF2 | 5.0 | 14.4 |

| HGF | 5.7 | 39.5 | TNF | 7.2 | 15.1 | ERBB2 | 4.9 | 21.3 | RABL6 | 4.7 | 19.7 |

| VEGF | 5.3 | 32.7 | VEGF | 7.0 | 15.0 | CSF | 4.2 | 4.8 | VEGF | 4.4 | 32.3 |

| FOXM1 | 5.0 | 19.4 | HGF | 6.9 | 22.0 | EGFR | 3.9 | 13.6 | HGF | 4.2 | 38.8 |

| CSF2 | 5.0 | 30.7 | ESR1 | 6.9 | 42.0 | IFNL1 | 3.8 | 5.8 | FOXM1 | 4.0 | 16.0 |

| E2F1 | 4.6 | 28.1 | EGF | 6.5 | 12.0 | IFNG | 3.7 | 21.3 | ESR1 | 3.9 | 31.1 |

| TBX2 | 4.4 | 13.0 | CSF2 | 6.5 | 14.0 | CCND1 | 3.7 | 18.5 | ERBB2 | 3.7 | 56.4 |

| E2F group | 4.2 | 15.8 | CTNNB1 | 6.3 | 13.0 | IL1A | 3.6 | 15.5 | FN1 | 3.7 | 7.5 |

| IFNA1 | 3.7 | 6.4 | SMARCA4 | 6.2 | 11.0 | RABL6 | 3.6 | 5.1 | TBX2 | 3.6 | 12.2 |

| IFNL1 | 3.6 | 13.0 | IFNG | 5.9 | 15.0 | OSM | 3.5 | 15.6 | EGF | 3.4 | 32.6 |

| NUPR1 | −6.2 | 15.6 | let-7 | −6.0 | 19.0 | GATA4 | −4.8 | 11.6 | TP53 | −5.2 | 53.0 |

| let-7 | −5.0 | 17.0 | CD3 | −5.1 | 15.0 | IL10RA | −4.3 | 7.4 | CDKN2A | −4.3 | 10.5 |

| KDM5B | −4.5 | 10.7 | SPDEF | −4.2 | 8.0 | MYOCD | −3.9 | 11.2 | let-7 | −3.9 | 16.0 |

| IRGM | −4.5 | 14.8 | KDM5B | −4.1 | 7.5 | IL1RN | −3.6 | 8.1 | RB1 | −3.8 | 17.7 |

| TP53 | −4.2 | 54.2 | IRGM1 | −4.0 | 9.0 | IRGM1 | −3.5 | 6.5 | NR3C1 | −3.5 | 7.9 |

| SPDEF | −4.1 | 10.2 | TRIM24 | −4.9 | 4.0 | HAND2 | −3.3 | 5.7 | SPDEF | −3.4 | 8.5 |

| RBL2 | −4.0 | 13.7 | RB1 | −3.9 | 14.0 | SRF | −3.3 | 11.1 | PPARG | −3.3 | 13.0 |

| BNIP3L | −4.0 | 17.3 | RBL2 | −3.9 | 7.2 | ACKR2 | −3.2 | 5.3 | let-7a-5p | −3.3 | 4.3 |

| CDKN2A | −3.9 | 7.3 | IL1RN | −3.8 | 2.2 | PTEN | −3.2 | 5.0 | IRGM1 | −3.2 | 7.2 |

| TRIM24 | −3.8 | 18.2 | CD28 | −3.6 | 8.2 | POU5F1 | −3.0 | 2.4 | CR1L | −3.1 | 8.9 |

The upstream regulatory pathways represented more than one study in the meta-analysis indicated in bold

The TP53 regulatory pathway was predicted to be the most inhibited with a z-score of −3.113 and a p-value of 4.05E-19 (Table 1). In our sample, 99 differentially expressed genes were downstream of the TP53 pathway (Additional file 10). Inhibition of the TP53 pathway is a hallmark of carcinogenesis and is predicted in our ESCC dataset, as well.

Functional meta-analysis of gene expression of ESCC in diverse ethnic groups

To determine whether African-American ESCC implicates genes that are unique or shared by ESCC of other ethnic groups, we performed a meta-analysis that included our African-American ESCC expression data and data from seven studies published in publicly available datasets in the GEO database. We note that our expression profiling data is the first such study in African-American ESCC to be deposited in the GEO repository. ESCC expression profiles in GEO included those generated in Japan (GSE17351) [25], Hong Kong, China (GSE33810) [29] and from various parts of China (GSE23400 [27], GSE20347 [26], GSE45670 [30], GSE33426 [28], and GSE29001 [28]). Ten genes that underwent the highest changes in expression in these studies are listed in the Additional file 11. Of the up-regulated genes, KRT17 was over-expressed in two other studies, the rest of the up-regulated genes were ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1), Profilin 2 (PFN2), Glycoprotein Nmb (GPNMB). Six out of 10 down-regulated genes (CRISP3, TMPRSS11B, CLCA4, SCEL, SLURP1, KRT78) were shared with four other studies.

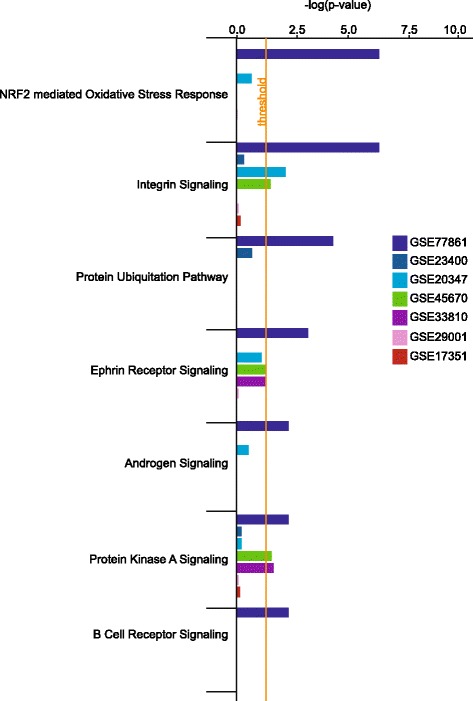

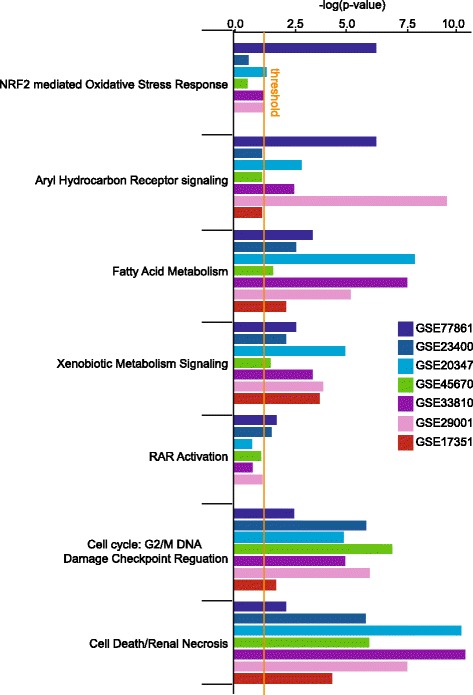

Analysis of the functional outcome of expression profiles from all microarray studies showed that NRF2-mediated oxidative stress pathway was significantly enriched only in our dataset (Fig. 4). Likewise, the significant enrichment of ubiquitination, androgen, and B- cell receptor signaling pathways was revealed only in our dataset. Integrin, ephrin receptor and protein kinase A signaling pathways were shared by at least two or more studies at or above the significance threshold.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of the most enriched pathways in ESCC. Dark navy bars represent our dataset. Dark blue, blue, green, purple, pink, and red bars represent the data sets of GSE23400, GSE20347, GSE45670, GSE33810, GSE29001, GSE17351, respectively.

It was important to examine the dysregulation of genetic components of the detox networks in the ESCC microarray expression datasets. All studies showed enrichment of toxicology pathways than other signaling pathways (Fig. 5). Interestingly, our dataset contained the highest number of genes in the NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response pathway while in other studies this number was either at or below the significance threshold. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, fatty acid metabolism, xenobiotic metabolism signaling, G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation and cell death genes were significantly perturbed in all studies. In our dataset (GSE77861) and in GSE23400 [27], the number of genes in retinoic acid receptor signaling was above the significance threshold.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the toxicology pathway indicated the enrichment of NRF2 pathway in our dataset. Dark navy bars represent our dataset. Dark blue, blue, green, purple, pink, and red bars represent the data sets of GSE23400, GSE20347, GSE45670, GSE33810, GSE29001, GSE17351, respectively.

Meta-analysis of the upstream regulatory pathways of ESCC in various ethnic groups

Meta-analysis of all available ESCC gene expression profile datasets showed a distinctive upstream regulatory pathway in African-Americans that highlighted a significant enrichment of the NRF2 mediated oxidative stress response pathway (Table 1). The activated pathways such as CBX5, insulin, MEK, NFE2L2, ANXA7, HSF2, NFE2L1, and PLIN5 were either uniquely represented in our study or shared with only one other study. Six out of eight datasets predicted the activation of upstream pathways of E2F and RABL6 although the rankings of z-score of these pathways were diverse (Table 1 and Additional file 9). FOXM1 was also projected as one of the common activated upstream pathways. Regardless of the z-score rankings, the activation of angiopoietin 2 pathway is the third highly represented upstream pathway in five of the studies (Additional file 9). The activation of fibronectin, and beta-catenin pathways as upstream regulators was revealed in five studies that included ours.

The predicted inhibited upstream pathways were divergent among the studies. While the TP53 pathway was predicted to be the top inhibited pathway in our study, the most common inhibited pathways including CDKN1A, IRF4, KDM5B, ACKR2, BNIP3L, DYRK1A were found in all datasets except in our study. In contrast, our dataset exclusively demonstrated the inhibition of FGFR1, ESRRA, EHF, and IL13 pathways.

Discussion

ESCC is the predominant esophageal carcinoma subtype worldwide occurring in specific geographic areas and in various countries including China, Japan, Iran, Italy and France [8, 31]. In the United States, a high incidence of ESCC has been reported in the District of Columbia and coastal areas of the southern states [32]. ESCC occurs at a 5-fold greater frequency among African-Americans than among white Americans while the converse has been observed for EAC [7, 33]. Even though five-year survival rates increased in both whites and black between 2004 and 2010, the mortality rate for esophageal carcinoma is still far greater in blacks than among whites [33–35]. Notably, in recent years, an increased incidence of EAC has been observed, particularly among whites [1, 34]. Altogether, these distinctive features indicate geographic and racial disparities in esophageal cancer [31].

We conducted a transcriptome analysis to identify the molecular repertoire involved in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in African-American males. To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate and analyze the global gene expression pattern of stage IV ESCC in African-Americans.

Heavy alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and poor diet are environmental risk factors for ESCC. Our findings in African-American ESCC reveal dysregulation of genes involved in detox networks, including NRF2 pathway, which is a primary mediator of detoxification and metabolism responses (Additional file 5) [36]. Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (NFE2L2) gene encodes a transcription factor NRF2 that regulates the transcription of antioxidant/electrophile response element (ARE)-containing target genes in response to oxidative and/or toxic environmental changes. The NRF2 pathway also regulates wound healing, resolution of inflammation, autophagy, ER stress response and unfolded protein response [37], apoptosis, differentiation of keratinocytes [38] and the embryonic development of the esophagus in response to growth factor-induced ROS production [39, 40].

The role of NRF2 pathway is cancer-type dependent. NRF2 protects against chemical carcinogen-induced carcinogenesis in the stomach, bladder and skin [41]. However, NRF2 activation plays an oncogenic role in lung, head and neck, ovarian and endometrial cancers [41]. Previous studies conducted in Asian samples demonstrated that higher expression of NRF2 is positively correlated with lymph node metastasis and drug resistance in ESCC [42]. Mutations in NFE2L2 confer malignant potential and resistance to therapy in advanced ESCC [43]. However, only 10% of Asian ESCC carry mutations in the NFE2L2 gene or its negative regulator KEAP1 [44]. Consistent with this data, our meta-analysis of gene expression profiles only showed a modest involvement of NRF2 in toxicology pathways in Asian ESCC datasets. IPA demonstrated the enrichment of NRF2 pathway in ESCC with high confidence in our dataset, suggesting a unique molecular signature of African-American ESCC. The significance of NRF2 pathway in African-American ESCC merits further functional evaluation.

In our CGH data, we previously found a loss of 7q in >50% of ESCC from African-American males [13]. Transcriptome mapping identified four genes located in the 7q21.1–22.3 region among which is the cytochrome P450 gene cluster that includes CYP3A5, CYP3A7, CYP3A4, and CYP3A43. It is noteworthy that our analysis indicates a significant loss of expression of CYP3A5 in addition to the down-regulation of three other genes that encode cytochrome P450 enzymes. It is well established that CYP3A enzymes metabolize more than half of the drugs used clinically [45]. Cytochrome P450 enzymes are also active in metabolizing toxic compounds thus their loss potentially contributes to carcinogenesis.

The persistent metabolic imbalance and tumor promoters found in cigarette smoking activate growth-promoting, cancerous conditions. Thus, the continual activation of NRF2 pathway could provide an adaptation mechanism to environmental toxicant especially in cancers [37]. Aryl hydrocarbon signaling, fatty acid, and xenobiotic metabolism also share some of the proteins that function in the NRF2 pathway. Therefore, the effect of the dysregulated NRF2 pathway may amplify the impairment of the dynamics of these pathways. In addition to response to toxins, NRF2 might promote cell proliferation of cancer cell by reprogramming metabolism to anabolic pathways [46]. However, further studies are required to investigate the causal association of NRF2 pathway in the esophageal tumor development in African-Americans. Future genomic studies are important to evaluate the mutational spectra of NFE2L2 or KEAP1 in African-American ESCC.

Recent studies that outlined the genomic and molecular characterization of esophageal carcinoma in the Asian population suggested the dysregulation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-MAPK-PI3K, NOTCH, Hippo, cell cycle, and epigenetic pathways as the primary molecular mechanism of ESCC [44, 47]. The amplification or over-expression of FGFR1, MET, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB4, and IL7R was observed in the majority of the patients and has been suggested as main drivers for the ESCC tumorigenesis [47]. Our meta-analysis of ESCC expression datasets indicated that the activation of growth factors and or their receptors, RABL6, FOXM1, CCND1, and CTNNB1 are upstream signaling drivers of the cellular growth of ESCC.

The upstream regulatory role of RABL6 was predicted in six out of eight ESCC datasets. RABL6 gene encodes a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases. The encoded protein RABL6, also known as RBEL or PARF, binds to both GTP and GDP and may play a role in cell growth and survival. Overexpression of this gene may play a role in breast, and pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis [48–50]. Functional analysis of RABL6 in ESCC warrants further study.

The most common inhibited upstream regulatory pathways are TP53 and KDM5B across most of the ESCC datasets. Studies have shown that TP53 negatively regulates NRF2-mediated gene expression [51]. The down-regulation of TP53 could synergistically sustain the activation of NRF2 seen in African-American ESCC. We previously identified a single nucleotide mutation of SCEL gene in both normal and squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus in African-Americans [52]. In our present study, SCEL is significantly under-expressed in African-American ESCC, and thus could play a role in squamous cell carcinogenesis as suggested by the down-regulation of this gene in larynx and hypopharynx [53], and in tongue squamous cell carcinoma [54].

The diversity among the inhibited upstream pathways implies the variety of susceptibility loci remain to be discovered in ESCC tumorigenesis, particularly the contribution of the deregulation of immune components. Given the differences in enriched pathways displayed by ESCC in various ethnic groups, it is possible that different genetic backgrounds have dissimilar responses to various environmental exposures. [55, 56].

Conceivably, our findings unmasked only a restricted view of the processes that are compromised in ESCC given the inherent limitations of microarray-based transcriptome profiling, the small sample size that was analyzed and incomplete modeling of biological reactions due to lack of functional data. However, the present study uncovered salient mechanistic aspects of the squamous esophageal cellular system in African-Americans, which to our knowledge, have not been described previously.

Conclusion

Our expression profiling study and pathway analysis suggest a widespread and prominent disruption of detox networks as revealed by the involvement of the NRF2 pathway and loss of detoxifying enzymes as a potential distinctive molecular mechanism in African-American esophageal squamous cell carcinogenesis.

Additional files

The list of the demographics and risk factors of the patients. (XLSX 9 kb)

Analysis pipeline. (EPS 830 kb)

The characteristics of studies included in Meta-analysis. (XLSX 11 kb)

The gene expression data file. (XLSX 118 kb)

The description of 25 networks found enriched in our data set by IPA. (XLSX 13 kb)

Fifteen canonical pathways that were significantly enriched in African-American ESCC. (EPS 1053 kb)

The list of the gene constituents of fifteen canonical pathways that were presented in Additional file 5. (XLSX 43 kb)

The role of NRF2 pathway and transcriptional targets of NRF2 which are differentially expressed in our dataset. (EPS 994 kb)

The meta-analysis of ESCC gene expression studies. (XLSX 438 kb)

The schematic representation of 99 differentially expressed genes that were downstream of the TP53 pathway. (EPS 27906 kb)

The table of top ten of the most differentially expressed genes in the studies contributed in the meta-analysis. (EPS 1532 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Washington DC VA Medical Center and the Institute for Clinical Research for their support.

Funding

Elsa U. Pardee Foundation.

Recipient: Robert Wadleigh MD, MS.

Role of the funding body: The Elsa U. Pardee Foundation approved the study design, the plans for sample collection, and data analysis before releasing the funds. The foundation also received a progress report during the study term and a final report at the end of the study term. The funding body did not contribute to the preparation and the revision of the manuscript.

The Robert Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust.

Recipient: Robert Wadleigh MD, MS.

Role of the funding body: The Robert Leet and Clara Guthrie Patterson Trust approved the study design, the plans for sample collection, and data analysis before releasing the funds. The foundation also received a progress report during the study term and a final report at the end of the study term. The funding body did not contribute to the preparation and the revision of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data was deposited to the NCBI GEO database. The link to data is below; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=glstesispfoztcd&acc=GSE77861.

Authors’ contributions

HVE: Analyzed microarray data, performed pathway analysis, performed meta-analysis of expression profiling data, wrote and revised the manuscript. KJ: Analyzed the microarray raw data, and contributed to the interpretation of findings and intellectual content of the manuscript. SG: Performed RNA extraction and microarray experiments. DK: Coordinated patient sample collection, and contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript. GT: Provided patient samples, and assisted in the revision of the manuscript. HA: Provided patient samples, and assisted in the revision of the manuscript. EPH: Supervised microarray experiments and contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript. RGW: Designed the experiments, contributed for intellectual content, and co-wrote and assisted in the revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests in the manuscript.

This manuscript does not reflect the views of the U.S. Federal Government or any of its agencies.

Consent for publication

The participants permitted to publish the results.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was done under a protocol approved by the Washington DC VAMC Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to biopsy or surgery. The IRB ID for this study is 00707.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ABCC1

ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 1

- ABCC5

ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 5

- ACAA1B

acetyl-Coenzyme A acyltransferase 1B

- ACKR2

atypical chemokine receptor 2

- ACLY

ATP citrate lyase

- ACOX1

acyl-CoA oxidase 1

- ADH7

alcohol dehydrogenase 7 (class IV)

- AKR1B1

aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B

- ALD

ABCD1 ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 1

- ALDH3A1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family member A1

- ALDH7A1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 7 family member A1

- ANXA7

Annexin 7

- ARE

antioxidant/electrophile response element

- BLVRA

biliverdin reductase A

- BNIP3L

BCL2 interacting protein 3 like

- CBX5

chromobox 5

- CCND1

cyclin D1

- CDKN1A

cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- CEBPB

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta

- CGH

comparative genomic hybridization

- CLCA4

chloride channel accessory 4

- CRSP3

cysteine-rich secretory protein 3

- CTNNB1

catenin beta 1

- CYP3A4

cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 4

- CYP3A43

cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 43

- CYP3A5

cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 5

- CYP3A7

cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 7

- DYRK1A

dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 1A

- EAC

Adenocarcinoma of esophagus

- EC

esophageal cancer

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EHF

ETS homologous factor

- ELOVL5

ELOVL fatty acid elongase 5

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- ERBB2

erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- ERBB4

erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- ESRRA

estrogen related receptor alpha

- FABP5

fatty acid binding protein 5

- FGFR1

fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

- FOXM1

forkhead box M1

- FTL1

ferritin light polypeptide 1

- GCLC

glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GPX4

glutathione peroxidase 4

- HSF2

heat shock transcription factor 2

- IGHG1

immunoglobulin

- IL13

interleukin 13

- IL7R

interleukin 7 receptor

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- IRF4

interferon regulatory factor 4

- IRGM1

immunity related GTPase M

- KDM5B

lysine demethylase 5B

- KEAP1

kelch like ECH associated protein 1

- KRT17

keratin 17

- KRT78

Keratin 78

- MAPK

MAP kinase

- MEK

MAP kinse-ERK kinase

- MET

MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase

- MGST2

microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2

- NCBI

The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NFE2L1

nuclear factor erythroid-2–related factor 1

- NFE2L2

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2

- NRF2

nuclear factor erythroid-2–related factor 2

- ODC1

ornithine decarboxylase 1

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PLIN5

perilipin 5

- RAB5B

RAB5B, member RAS oncogene family

- RABL6

RAB, member RAS oncogene family-like 6

- RABL6

RAB, member RAS oncogene family-like 6

- RAF

Raf-1 proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- RT-PCR

Real time polymerase chain reaction

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma

- SCEL

sciellin

- SELK

selenoprotein K

- SLURP1

secreted LY6/PLAUR domain

- TMPRSS11B

transmembrane protease, serine 11B

- TNFRSF6B

Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6b

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3423-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Hayriye Verda Erkizan, Email: hayriye.erkizan@va.gov.

Kory Johnson, Email: johnsonko@ninds.nih.gov.

Svetlana Ghimbovschi, Email: sghimbovschi@childrensnational.org.

Deepa Karkera, Email: deepa.karkera@va.gov.

Gregory Trachiotis, Email: gregory.trachiotis@va.gov.

Houtan Adib, Email: houtan.adib@va.gov.

Eric P. Hoffman, Email: ehoffman@childrensnational.org

Robert G. Wadleigh, Phone: 202-745-8482, Email: robert.wadleigh@va.gov

References

- 1.Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381(9864):400–412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon H, Gibson MK. Molecular Outcome Prediction In: Jobe BA, Thomas CR, Hunter JG (eds) Esophageal cancer: principles and practice. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2009. pp. 771–82.

- 3.Chung CS, Lee YC, Wu MS. Prevention strategies for esophageal cancer: perspectives of the east vs. west. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29(6):869–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohashi S, Miyamoto S, Kikuchi O, Goto T, Amanuma Y, Muto M. Recent advances from basic and clinical studies of esophageal Squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1700–1715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(34):5598–5606. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Kwong DL, Cao T, Hu Q, Zhang L, Ming X, Chen J, Fu L, Guan X. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC): advance in genomics and molecular genetics. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28(1):84–89. doi: 10.1111/dote.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown LM, Hoover R, Silverman D, Baris D, Hayes R, Swanson GM, Schoenberg J, Greenberg R, Liff J, Schwartz A, et al. Excess incidence of squamous cell esophageal cancer among US black men: role of social class and other risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(2):114–122. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y, Ueda J, Wei W, Inoue M, Tanaka H. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):233–242. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita M, Kumashiro R, Kubo N, Nakashima Y, Yoshida R, Yoshinaga K, Saeki H, Emi Y, Kakeji Y, Sakaguchi Y, et al. Alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, and the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: epidemiology, clinical findings, and prevention. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15(2):126–134. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shakeri R, Kamangar F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Nouraie M, Khademi H, Etemadi A, Islami F, Marjani H, Fahimi S, Sepehr A, et al. Is opium a real risk factor for esophageal cancer or just a methodological artifact? Hospital and neighborhood controls in case-control studies. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrici J, Eslick GD. Hot food and beverage consumption and the risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karkera JD, Balan KV, Yoshikawa T, Lipman TO, Korman L, Sharma A, Patterson RH, Sani N, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Wadleigh RG: Systematic screening of chromosome 18 for loss of heterozygosity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1999, 111(1):81-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pack SD, Karkera JD, Zhuang Z, Pak ED, Balan KV, Hwu P, Park WS, Pham T, Ault DO, Glaser M, et al. Molecular cytogenetic fingerprinting of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization reveals a consistent pattern of chromosomal alterations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25(2):160–168. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199906)25:2<160::AID-GCC12>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakai N, Kajiyama Y, Iwanuma Y, Tomita N, Amano T, Isayama F, Ouchi K, Tsurumaru M. Study of abnormal chromosome regions in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by comparative genomic hybridization: relationship of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis to selected abnormal regions. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(5):415–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinomiya T, Mori T, Ariyama Y, Sakabe T, Fukuda Y, Murakami Y, Nakamura Y, Inazawa J. Comparative genomic hybridization of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: the possible involvement of the DPI gene in the 13q34 amplicon. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;24(4):337–344. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199904)24:4<337::AID-GCC7>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiomi H, Sugihara H, Kamitani S, Tokugawa T, Tsubosa Y, Okada K, Tamura H, Tani T, Kodama M, Hattori T. Cytogenetic heterogeneity and progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;147(1):50–61. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(03)00159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugimoto T, Arai M, Shimada H, Hata A, Seki N. Integrated analysis of expression and genome alteration reveals putative amplified target genes in esophageal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(2):465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tada K, Oka M, Tangoku A, Hayashi H, Oga A, Sasaki K. Gains of 8q23-qter and 20q and loss of 11q22-qter in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma associated with lymph node metastasis. Cancer. 2000;88(2):268–273. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<268::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du Plessis L, Dietzsch E, Van Gele M, Van Roy N, Van Helden P, Parker MI, Mugwanya DK, De Groot M, Marx MP, Kotze MJ, et al. Mapping of novel regions of DNA gain and loss by comparative genomic hybridization in esophageal carcinoma in the black and colored populations of South Africa. Cancer Res. 1999;59(8):1877–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen CC, Chen YJ, Chen JT, Hsia JY, Chen PM, Liu JH, Fan FS, Chiou TJ, Wang WS, Lin CH. Comparative genomic hybridization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: correlations between chromosomal aberrations and disease progression/prognosis. Cancer. 2001;92(11):2769–2777. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011201)92:11<2769::AID-CNCR10118>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong D, Lam A, Guan X, Law S, Tai A, Wong J, Sham J. Chromosomal aberrations in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma among Chinese: gain of 12p predicts poor prognosis after surgery. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(3):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin YR, Wang LD, Fan ZM, Kwong D, Guan XY. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of genetic aberrations associated with development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Henan, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(12):1828–1835. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carneiro A, Isinger A, Karlsson A, Johansson J, Jonsson G, Bendahl PO, Falkenback D, Halvarsson B, Nilbert M. Prognostic impact of array-based genomic profiles in esophageal squamous cell cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eric P Hoffman TA, John Palma, Teresa Webster, Earl Hubbell, Janet A Warrington, Avrum Spira, George Wright, Jonathan Buckley, Tim Triche, Ron Davis, Robert Tibshirani, Wenzhong Xiao, Wendell Jones, Ron Tompkins, and Mike West: Guidelines: Expression profiling — best practices for data generation and interpretation in clinical trials. Nat Rev Genet 2004, 5(3):229-237. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Nakagawa H, Rustgi AK. Expression data from esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. 2009. Obtained from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE17351.

- 26.Hu N, Clifford RJ, Yang HH, Wang C, Goldstein AM, Ding T, Taylor PR, Lee MP. Genome wide analysis of DNA copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity (CNNLOH) and its relation to gene expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:576. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su H, Hu N, Yang HH, Wang C, Takikita M, Wang QH, Giffen C, Clifford R, Hewitt SM, Shou JZ, et al. Global gene expression profiling and validation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its association with clinical phenotypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(9):2955–2966. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan W, Shih JH, Rodriguez-Canales J, Tangrea MA, Ylaya K, Hipp J, Player A, Hu N, Goldstein AM, Taylor PR, et al. Identification of unique expression signatures and therapeutic targets in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:73. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen K, Li Y, Dai Y, Li J, Qin Y, Zhu Y, Zeng T, Ban X, Fu L, Guan XY. Characterization of tumor suppressive function of cornulin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen J, Yang H, Liu MZ, Luo KJ, Liu H, Hu Y, Zhang X, Lai RC, Lin T, Wang HY, et al. Gene expression analysis of pretreatment biopsies predicts the pathological response of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas to neo-chemoradiotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1769–1774. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashktorab H, Nouri Z, Nouraie M, Razjouyan H, Lee EE, Dowlati E, El-Seyed el W, Laiyemo A, Brim H, Smoot DT. Esophageal carcinoma in African Americans: a five-decade experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(12):3577–3582. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1853-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickens A. Ethnic disparities in cancer of the esophagus. In: Esophageal cancer principles and practice. 1st edn. Edited by Jobe BA TC, Jr, Hunter JG. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2009. 137–141.

- 34.Brown LM, Devesa SS, Chow WH. Incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus among white Americans by sex, stage, and age. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(16):1184–1187. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015.

- 36.Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(12):931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:401–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D. Stress-activated cap‘n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Sci Signal. 2010;3(112):re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3112re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen H, Li J, Li H, Hu Y, Tevebaugh W, Yamamoto M, Que J, Chen X. Transcript profiling identifies dynamic gene expression patterns and an important role for Nrf2/Keap1 pathway in the developing mouse esophagus. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang M, Ku WY, Zhou Z, Dellon ES, Falk GW, Nakagawa H, Wang ML, Liu K, Wang J, Katzka DA, et al. BMP-driven NRF2 activation in esophageal basal cell differentiation and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(4):1557–1568. doi: 10.1172/JCI78850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaramillo MC, Zhang DD. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev. 2013;27(20):2179–2191. doi: 10.1101/gad.225680.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mao JT, Tangsakar E, Shen H, Wang ZQ, Zhang MX, Chen JX, Zhang G, Wang JS. Expression and clinical significance of Nrf2 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Xi Bao Vu Fen Zi Mian Vi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;27(11):1231–1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shibata T, Kokubu A, Saito S, Narisawa-Saito M, Sasaki H, Aoyagi K, Yoshimatsu Y, Tachimori Y, Kushima R, Kiyono T, et al. NRF2 mutation confers malignant potential and resistance to chemoradiation therapy in advanced esophageal squamous cancer. Neoplasia. 2011;13(9):864–873. doi: 10.1593/neo.11750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG, Hu XD, Shi XJ, Sun ZM, Zhang F, Zhao ZR, Li ZT, Liu ZY, et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(10):1097–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulussen A, Lavrijsen K, Bohets H, Hendrickx J, Verhasselt P, Luyten W, Konings F, Armstrong M. Two linked mutations in transcriptional regulatory elements of the CYP3A5 gene constitute the major genetic determinant of polymorphic activity in humans. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10(5):415–424. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitsuishi Y, Taguchi K, Kawatani Y, Shibata T, Nukiwa T, Aburatani H, Yamamoto M, Motohashi H. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(1):66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin DC, Hao JJ, Nagata Y, Xu L, Shang L, Meng X, Sato Y, Okuno Y, Varela AM, Ding LW, et al. Genomic and molecular characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(5):467–473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li YY, Fu S, Wang XP, Wang HY, Zeng MS, Shao JY. Down-regulation of c9orf86 in human breast cancer cells inhibits cell proliferation, invasion and tumor growth and correlates with survival of breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montalbano J, Jin W, Sheikh MS, Huang Y. RBEL1 is a novel gene that encodes a nucleocytoplasmic Ras superfamily GTP-binding protein and is overexpressed in breast cancer. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(52):37640–37649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagen J, Muniz VP, Falls KC, Reed SM, Taghiyev AF, Quelle FW, Gourronc FA, Klingelhutz AJ, Major HJ, Askeland RW, et al. RABL6A promotes G1-S phase progression and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell proliferation in an Rb1-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2014;74(22):6661–6670. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faraonio R, Vergara P, Di Marzo D, Pierantoni MG, Napolitano M, Russo T, Cimino F. p53 suppresses the Nrf2-dependent transcription of antioxidant response genes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(52):39776–39784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corona W, Karkera DJ, Patterson RH, Saini N, Trachiotis GD, Korman LY, Liu B, Alexander EP, De la Pena AS, Marcelo AB, et al. Analysis of Sciellin (SCEL) as a candidate gene in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(3a):1417–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nair J, Jain P, Chandola U, Palve V, Vardhan NR, Reddy RB, Kekatpure VD, Suresh A, Kuriakose MA, Panda B. Gene and miRNA expression changes in squamous cell carcinoma of larynx and hypopharynx. Genes Cancer. 2015;6(7–8):328–340. doi: 10.18632/genesandcancer.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye H, Yu T, Temam S, Ziober BL, Wang J, Schwartz JL, Mao L, Wong DT, Zhou X. Transcriptomic dissection of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Timme S, Ihde S, Fichter CD, Waehle V, Bogatyreva L, Atanasov K, Kohler I, Schopflin A, Geddert H, Faller G, et al. STAT3 expression, activity and functional consequences of STAT3 inhibition in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas and Barrett’s adenocarcinomas. Oncogene. 2014;33(25):3256–3266. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Du XL, Wang CJ, Lin DC, Ruan X, Feng YB, Huo YQ, Peng H, Cui JL, Zhang TT, et al. Reciprocal activation between PLK1 and Stat3 contributes to survival and proliferation of esophageal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):521–530. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The list of the demographics and risk factors of the patients. (XLSX 9 kb)

Analysis pipeline. (EPS 830 kb)

The characteristics of studies included in Meta-analysis. (XLSX 11 kb)

The gene expression data file. (XLSX 118 kb)

The description of 25 networks found enriched in our data set by IPA. (XLSX 13 kb)

Fifteen canonical pathways that were significantly enriched in African-American ESCC. (EPS 1053 kb)

The list of the gene constituents of fifteen canonical pathways that were presented in Additional file 5. (XLSX 43 kb)

The role of NRF2 pathway and transcriptional targets of NRF2 which are differentially expressed in our dataset. (EPS 994 kb)

The meta-analysis of ESCC gene expression studies. (XLSX 438 kb)

The schematic representation of 99 differentially expressed genes that were downstream of the TP53 pathway. (EPS 27906 kb)

The table of top ten of the most differentially expressed genes in the studies contributed in the meta-analysis. (EPS 1532 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data was deposited to the NCBI GEO database. The link to data is below; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=glstesispfoztcd&acc=GSE77861.