Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder and the most common form of dementia characterized by cognitive and memory impairment. One of the mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of AD, is the oxidative stress being involved in AD‘s development and progression. In addition, several studies proved that chronic viral infections, mainly induced by Human herpesvirus 1 (HHV-1), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Human herpesvirus 2 (HHV-2), and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) could be responsible for AD’s neuropathology. Despite the large amount of data regarding the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a very limited number of therapeutic drugs and/or pharmacological approaches, have been developed so far. It is important to underline that, in recent years, natural compounds, due their antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties have been largely studied and identified as promising agents for the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. The ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid, (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG), is the main and most significantly bioactive polyphenol found in solid green tea extract. Several studies showed that this compound has important anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic properties as well as protective effects against neuronal damage and brain edema. To date, many studies regarding the potential effects of EGCG in AD’s treatment have been reported in literature. The purpose of this review is to summarize the in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies on the use of EGCG in the prevention and the treatment of AD as well as to offer new insights for translational perspectives into clinical practice.

Keywords: (−) - Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCG), Natural compound, Inflammation, Oxidative stress, Alzheimer’s disease

Background

The term dementia covers a large range of heterogeneous diseases at clinical and histopathological levels. Loss of memory and progressive dysfunctions of neuronal materials are features commonly present in patients with dementia and severely impairing theirs quality of life. Classically, dementia is defined as “syndrome caused by neurodegeneration” whereas Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is the most common type of dementia, accounting for an estimated 60 to 80% of cases. Although the exact pathophysiology of AD is still unclear, emerging evidence suggests that microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory responses play an important role in AD’s pathogenesis [1, 2]. In addition, several studies proved that chronic viral infections, mainly induced by Human herpesvirus 1 (HHV-1), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Human herpesvirus 2 (HHV-2), and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) could be responsible for AD’s neuropathology. It is of note that microglia, resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), are significantly involved in the neuroinflammation process. Current evidences on AD’s mechanism showed that the principal pathological features of AD are represented by the accumulation of soluble amyloid β peptide (Aβ) in the brain and the neurofibrillary tangles [3]. Aβ is considered an important neuroinflammatory stimulus for microglia. Moreover, it is of note that Aβ-dependent microglial activation induces neuronal injury due to the secretion of various pro-inflammatory molecules such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), interleukin (I) L-6, IL-1β, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reactive nitrogen species (NOS) [4]. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress processes are responsible for the impairments of neurovascular unit’s functions, leading to axonal demyelination, local hypoxia–ischemia, and reduced repair of white matter damages [5].

Despite the large amount of data published on the AD’s pathogenesis, a limited number of therapeutic drugs have been developed so far. Natural compounds have been identified as promising agents for the prevention and treatment of neurological disorders [6] and AD due their antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties [7]. As a consequence, many investigations have been performed, with the aim of to evaluate the neuroprotective effects of nutraceuticals, such as resveratrol [8], curcumin [9], pinocembrin [10], caffeine [11], the combination of Panax ginseng, Ginkgo biloba, and Crocus sativus [12], and salvia triloba associated to Piper nigrum [13].

Catechins flavonoids are contained in Green tea extract (GTE) and are defined as the active components of green tea, accounting for its therapeutic properties. The ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid, (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate [EGCG; (2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-3-yl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate] (Pubchem CID: 65,064), represents the principal bioactive polyphenol in the solid GTE (65% catechin content). Several studies showed that EGCG has important anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory properties [14, 15] with potential neuroprotective effects against cerebrovascular diseases. For examples, Ahn et al. showed that EGCG was able to inhibit the production of TNFα-induced monocyte chemotactic protein-1 from vascular endothelial cells [16], whereas Lee et al. studied the protective effects of EGCG against brain edema and neuronal damage after unilateral cerebral ischemia in gerbils [17]. In addition, it has been proved that EGCG bypassed the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and to reach the functional parts of the brain [18]. Moreover, EGCG appears to be safe even when administered at relatively high dose. Indeed, as Lee et al. showed, an amount up to 6 mg/kg of EGCG can be used without any side effects [19].

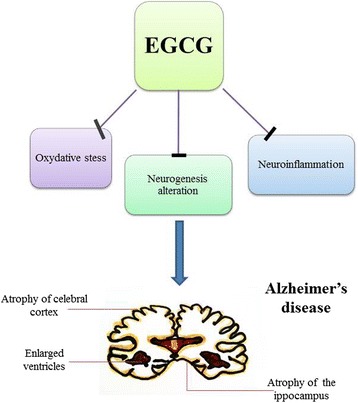

As regards to the role of EGCG in the treatment of AD’s disorder, a large amount of in vitro and in vivo studies, have been reported so far [19–37], indicating that EGCG plays a neuroprotective role and be potentially used as therapeutic agent for AD’s treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The potential effects of EGCG in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis

On the other side, studies have been also performed by using computational methods. For example, Ali et al., in order to demonstrate a potential role of cholinesterase inhibitors for AD’s treatment, performed an in silico analysis by using green tea polyphenols. Data emerged from this study, suggested that the cholinergic neurotransmission was enhanced by these synthetically compounds through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzymes [38].

The aim of this article is to highlight the potential use of EGCG for the prevention and/or treatment of AD, by summarize the pre-clinical studies reported in literature. Insights for translational perspectives into clinical practice are also given.

Anti-neuroinflammatory properties of EGCG in the prevention and the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

-

In vitro studies: an update

In vitro studies on the anti-neuroinflammatory effects of EGCG have been performed on different cells lines including MC65, EOC 13.31, SweAPP N2a, N2a/APP695, DIV8, CHO, and M146 L cells (Table 1). Results from these studies showed that the anti-neuroinflammatory capacity of EGCG is mainly associated to the inhibition of microglia-induced cytotoxicity.

Lin et al. demonstrated that EGCG was able to suppress the neurotoxicity induced by Aβ, through the activation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and the inhibition of c-Abl/FE65 nuclear translocation [20]. This was a relevant finding, since it is of note that c-Abl is a cytoplasmic nonreceptor tyrosine kinase involved in the development of the nervous system and implicated in the regulation of cell apoptosis, whereas the β-isoform of GSK3 is a proline-directed serine-threonine kinase involved in neuronal cell development and energy metabolism [21]. These data suggest that c-Abl/GSK-3β signaling is involved in neuronal loss, neuroinflammation and gliosis. It is of note that, related to AD’s pathogenesis, the proteolytic processing of a transmembrane glycoprotein, known as amyloid precursor protein (APP), is responsible for the Aβ’s origin [22]. Other investigations have been conducted to evaluate the effect of EGCG on Aβ-induced inflammatory responses in microglia. To this regard, Wei et al., investigated on the inhibitory effects of EGCG on microglial activation induced by Aβ and on neurotoxicity in Aβ-stimulated EOC 13.31 microglia. Results revealed that that EGCG was able to suppress the expression of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and to restore the levels of intracellular antioxidants against free radical-induced pro-inflammatory effects in microglia, the nuclear erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) and the heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [23]. In addition, EGCG suppressed Aβ-induced cytotoxicity by reducing ROS-induced NF-κB activation and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 signaling. Taken together these data suggest that EGCG is able to inhibit the neuroinflammatory response of microglia induced by Aβ and to protect against indirect neurotoxicity through several mechanisms.

Previously, Rezai-Zadeh et al. demonstrated that GTE reduced the generation of Aβ in murine neuron-like cells (N2a) transfected with the human “Swedish” mutant APP (SweAPP N2a cells) and activated the nonamyloidogenic processing of APP, also promoting its α-secretase cleavage [24].

One of the processes involved in the amyloid formation cascade, is the β-sheet formation. This event is frequently associated with cellular toxicity in many of human protein misfolding diseases, including AD. It has been reported that EGCG was able to interfere with this cascade, by redirection of prone polypeptides’ aggregation into off-pathway protein assemblies [25]. In another study, Bieschke et al. showed that EGCG converted the large mature Aβ fibrils into smaller forms with no toxicity for mammalian cell [26]. A recent study conducted by Chesser et al., proved that EGCG in DIV8 primary rat cortical neurons, was able to enhance the clearance of AD-relevant phosphorylated tau species, indicating that EGCG could be used as an adjuvant agent for AD’s treatment [27]. Similar findings were obtained by Chang et al. The authors demonstrated that EGCG reduced β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation in M146 L and CHO cells [28]. Finally, very recently it has been reported that EGCG inhibited β-Amyloid generation and oxidative stress involvement of nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) in N2a/APP695 cells [29].

All these data suggest that EGCG may be considered an important agent with neuroprotective properties against AD.

-

In vivo preclinical studies: an-update

The neuroprotective effects of EGCG have been also demonstrated by in vivo experiments on several animal models (Table 2). The first study was reported by Rezai-Zadeh et al. [24]. The authors described that EGCG was able to decrease Aβ levels and plaques formation in a transgenic mouse model of “Swedish” mutant APP when was injected intraperitoneally (20 mg/kg). Similar results were obtained by the same group of researchers, when EGCG administered orally in drinking water (50 mg/kg), reduced Aβ deposition in the same mutant mice [30]. In another study based on the generation of transgenic mouse models of AD, Li et al., [31] investigated on EGCG (orally 20 mg/kg/day, for 3 months) capacity to interfere with Aβ deposits in different brain areas. Data emerged by immunohistochemistry, showed that Aβ deposits were reduced by 60% in the frontal cortex and 52% in the hippocampus. A reduction of Thioflavine-S histochemistry labelling compact plaques was also detected in both regions. In addition, the percentage of CD45, a marker of microglial activation, was lower than 18% in the cortex and then 28% in the hippocampus respect to those observed in the control cohort. New insights on the role of EGCG in AD’s treatment have been reported by Smith et al. [32]. The authors engineered nanolipidic EGCG particles to improve oral’s bioavailability of EGCG. By using this system in mouse model of AD’s disease, the ability of EGCG for the treatment of AD was enhanced more than two-fold respect to treatment with free EGCG.

The role of EGCG in AD’s treatment, was also described by Giunta et al., in an interesting study in which was used Fish oil (8 mg/kg/day) combined to EGCG (62.5 mg/kg/day or 12.5 mg/kg/day) in a mouse model of AD. Results obtained from these experiments, showed that co-treatment of N2a cells with fish oil and EGCG increased the production of sAPP-alpha respect to either compound alone, indicating that these compounds were able to make a synergetic action on the inhibition of cerebral Aβ deposits [33].

More recently, Lee et al. [19] tested the effects of EGCG on neuroinflammation and amyloidogenesis, in mice with systemic inflammation. The authors demonstrated that EGCG was able to prevent memory impairment induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and apoptotic neuronal cell death. Moreover, EGCG prevented LPS-induced activation of astrocytes and increased cytokines expression (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), suggesting that EGCG could be considered a therapeutic agent for neuroinflammation-associated AD. In animal another model of dementia, generated by infusion of streptozotocin (STZ) into intracerebroventricular (ICV) of rats, Biasibetti et al., showed that EGCG (10 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) completely abrogated the cognitive deficit by influencing the glial-specific calcium binding protein S100B content in the hippocampus, the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, the glutathione peroxidase activity, the nitric oxide (NO) metabolites, and ROS content [34].

He et al., by using an AD’s mouse model generated by D-gal, showed that EGCG had a protective effect on AD by decreasing the expression of APP and Aβ in the hippocampus of mice [35]. Similarly, Lin et al. proved that EGCG impaired the formation of Aβ, through the inhibition of APP proteolysis, cAbl/FE65 complex nuclear translocation and GSK3 activation [20].

Since insulin signaling plays a significant role in the regulation of synaptic activities involved in learning and memory processes, insulin resistance – expressed as increased phosphorylation levels of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) - and subsequent alteration in signaling pathways, may contribute to the cognition impairment in AD’s patients [36]. Interestingly, Jia et al. demonstrated that EGCG reduced the spatial memory impairment (AD-related cognitive deficit) in APP/PS1 mice (bearing brain insulin resistance) by inducing IRS-1 signaling defects in the hippocampus, in a dose dependent manner [37].

In another study, was reported that EGCG reduced Aβ accumulation in vitro and rescued cognitive deterioration in senescence-accelerated mice P8 (SAMP8). The authors showed that EGCG attenuated the cognitive deterioration in AD’s mouse model by upregulation of neprilysin (NEP) expression [28].

Taken together, these data strongly suggest that EGCG could be used as a therapeutic agent for the treatment and the prevention of AD.

Table 1.

A summary of in vitro studies on the role of EGCG on AD prevention

| Cell lines | Drug and dosage | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MC65 | EGCG 20 μM | EGCG reduced the Aβ levels by enhancing endogenous APP proteolysis and decreased nuclear translocation of c-Abl. | [20] |

| EOC 13.31 | EGCG 5 to 20 μM | EGCG suppressed the expression of Aβ-induced TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS, and restored the levels of intracellular antioxidants Nrf2 and HO-1. | [23] |

| SweAPP N2a | GTE | EGCG reduced the Aβ generation and activated nonamyloidogenic processing of APP by promoting its α-secretase cleavage. | [24] |

| Div8 | EGCG 12.5–50 μM | EGCG induced an increase in the key autophagy adaptor proteins NDP52 and p62. | [27] |

| M146 L, CHO | EGCG 16–32 μmol/L | EGCG reduced the accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ). | [28] |

| N2a/APP695 | EGCG (5–100 μM) | EGCG suppressed the production of Aβ and reduced inflammation, oxidative stress and cell apoptosis. | [29] |

Table 2.

Pre-clinical in vivo studies on the anti-neurodegenerative properties of EGCG in AD

| Animal models | EGCG dose and route | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tg2576 APP mice | 20 mg/kg daily for 4 months (oral gavage) | EGCG impaired Aβ formation by inhibiting APP proteolysis and by inhibiting cAbl/FE65 complex nuclear translocation and GSK3 activation. | [20] |

| Swedish mutant APP-overexpressing mice (Tg APPsw line 2576) | 20 mg/kg (intraperitoneally) | EGCG induced APP processing with reduction of cerebral amyloidosis. | [24] |

| APP transgenic mice | 20 mg/kg/day, for 3 months (oral gavage) | Aβ deposits were reduced by 60% in the frontal cortex and 52% in the hippocampus. | [31] |

| AD mouse model | Nanolipidic particles loaded with EGCG | Improved the bioavailability and α-secretase activity induced by EGCG. | [32] |

| Tg2576 mice | Fish oil (8 mg/kg/day) and EGCG (oral gavage, 62.5 mg/kg/day or 12.5 mg/kg/day) | Fish oil enhanced bioavailability of EGCG versus EGCG treatment alone. Synergetic effect of Fish oil and EGCG on the inhibition of cerebral A β deposits. | [33] |

| Wistar rat model of dementia | 10 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks, oral gavage. ICV infusion of STZ (3 mg/kg) | EGCG completely abrogated the cognitive deficit, S100B content in the hippocampus, AChE activity, glutathione peroxidase activity, NO metabolites, and ROS content | [34] |

| ICR mice model of systemic inflammation | 1.5 and 3 mg/kg for 3 weeks (Oral gavage). LPS (250 μg/kg) intraperitoneal | EGCG prevented LPS-induced memory impairment, apoptotic neuronal cell death, and microglia activation | [19] |

| AD mouse model induced by D-gal | 2 mg/(kg/ day) or 6 mg/(kg/day) for 4 weeks, oral gavage | EGCG decreased the expression of APP and beta-Amyloid in the hippocampus of mice. | [35] |

| APP/PS1 mice | 2 mg/(kg/day) or 6 mg/(kg/day) for 4 weeks, oral gave | EGCG treatment inhibited TNF-α/JNK signaling, increased the phosphorylation of Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3β. | [37] |

| SAMP8 mice | 5 and 15 mg/kg, for 60 days, intragastric | EGCG induced reduction in Aβ accumulation and increased NEP expression | [28] |

Translational perspectives of EGCG’s use into clinical practice

Promising results obtained by in vitro and in vivo studies on the use of EGCG as valuable therapeutic options for neurodegenerative disorders and cancer treatments, encourage its commitment to translation into clinical practice [39, 40].

-

The bioavailability of EGCG in the brain: a discrepancy between animals and humans-based studies

Despite these encouraging results, there is still a translational gap between in vitro, in vivo and clinical studies with EGCG in neurodegenetative disease treatment. This can be associated to poor data reported on the bioavailability of EGCG in the brain, a feature extremely necessary for its neuroprotrective role. In vivo studies performed on animal models showed that repeated administration of EGCG, increased its accumulation in the brain [41, 42]. Opposite results were obtained in a study performed on six human subjects which assumed green tea by drinking. The products of green tea’s metabolism, (i.e. flavan-3-ol methyl-glucuronide and sulfate metabolites) were not able to reach the brain, thus remaining in the bloodstream [43]. These discrepancy can be associated to different causes, as reported by Mähler et al.in a review on this topic (i.e. dose, time point of EGCG treatment and different catechin metabolism between animals and humans) [39]. When EGCG is able to reach the brain, it regulates many biological processes and molecular signaling pathways involved in neurodegenerative disorders, included AD, as previously reported based on convincing results of in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies [44]. Unfortunately, these mechanisms are not completely elucidated in clinical studies probably due to the absence of standardization of disease severity in humans and in green tea preparations and its derivatives.

This strongly suggest the needing of more detailed and specific studies on EGCG’s brain and plasma bioavailability, on its efficacy and safety in patients, and on possible interactions with other drugs.

-

Clinical trials

Despite the encouraging data obtained from pre-clinical studies, several pivotal issues, regarding EGCG dose levels and administration frequency as well as genetic and epigenetic modulations involved in the metabolism and distribution of the active compounds in humans, remain to be explored [45].Previous findings from a cross-sectional study showed a negative association between green tea consumption and the prevalence of cognitive impairment in elderly individuals over 70 years old [46]. Thus, there is a discrepancy about the effects of GTE compounds on cognitive functions [47].

Several clinical studies have been performed to evaluate the acute effects of EGCG and other constituents of tea, such as L-theanine, on cognitive function (e.g., attention) and mood. The results obtained, showed that tea consumption had significant acute benefits on mood and work performance and creativity [48, 49]. Another clinical study performed on 27 healthy human adults treated with EGCG (orally administered in a single dose of 135 mg), reported that EGCG was able to modulate cerebral blood flow parameters, without affecting cognitive performance or mood [50]. Similarly, Scholey et al. showed that EGCG administration (300 mg) was associated with reduced stress, increased calmness and increased electroencephalographic activity (increased alpha, beta and theta activities) in the midline frontal and central brain regions [51]. Ide et al. showed that green tea consumption in subjects with cognitive dysfunction (2 g/day for 3 months, approximately equal to 2 to 4 cups of tea/day) significantly improved cognitive performance [52].

It is of note that the clinical symptoms of AD do not occur immediately. For this reasons, acute results of EGCG or other natural compounds on neurocognitive capacities, cannot be predictive of efficacy in more complex neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD’s syndrome. To date, one ongoing clinical trial is investigating on the effects of EGEG in early state of AD patients co-medicated with acetylcholine esterase inhibitors (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00951834) [53].

In order to evaluate the clinical effects of EGCG on AD, are necessary: (i) more detailed in vitro and in vitro studies with the purpose of dissect the underlying molecular mechanisms by which EGCG interferes with AD pathogenesis; (ii) clinical studies exploring the long-term effects of EGCG on cognitive functions; (iii) large size epidemiological studies concerning the consumption of EGCG and the progression of AD.

Conclusions

Several in vitro and pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that EGCG, the principal bioactive component found in green tea, has anti-inflammatory properties by modulating different molecular pathways. Regarding AD’s syndrome, in vitro and in vivo studies reviewed here, showed that EGCG mainly induces reduction in Aβ accumulation, by modulating several biological mechanisms. Promising results in the pre-clinical and in recent clinical studies largely encourage EGCG’s commitment to translation into a clinical therapeutic approach. However, EGCG dose levels and administration frequency remain to be explored, so more pre-clinical investigations and well-drawn clinical trials are extremely needed.

With the use of different integrated approaches, next studies will shed light on the use of EGCG as a targeted prevention and individualized treatment to patients with AD’s disease.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Alessandra Trocino and Mrs. Cristina Romano from the National Cancer Institute of Naples for providing excellent bibliographic service and assistance.

Funding

No funds were used for the preparation of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

The present review was mainly written by MC and SB. MM, VS and AC contributed to revise the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ

Amyloid β peptide

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- BChE

Butyrylcholinesterase

- CNS

Central nervous system

- EGCG

(−)-Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate

- GSK-3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- GTE

Green tea extract

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase-1

- ICV

Intracerebroventricular

- IL

Interleukin

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRS-1

Insulin receptor substrate-1

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NEP

Neprilysin

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Reactive nitrogen species

- Nrf2

Nuclear erythroid-2 related factor 2

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- S100B

Calcium-binding protein B

- SAMP8

Senescence-accelerated mice P8

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Contributor Information

Marco Cascella, Email: m.cascella@istitutotumori.na.it.

Sabrina Bimonte, Phone: +39 081 5903221, Email: s.bimonte@istitutotumori.na.it.

Maria Rosaria Muzio, Email: maramuzio@yahoo.it.

Vincenzo Schiavone, Email: enzo.schiavone@alice.it.

Arturo Cuomo, Email: a.cuomo@istitutotumori.na.it.

References

- 1.Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadav A, Collman RG. CNS inflammation and macrophage/microglial biology associated with HIV-1 infection. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacolog. 2009;4:430–447. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9174-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iqbal K. Grundke-Iqbal I Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration: significance, etiopathogenesis, therapeutics and prevention. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:38–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agostinho P, Cunha RA, Oliveira C. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2766–2778. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iadecola C. The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cascella M, Muzio MR. Potential application of the Kampo medicine goshajinkigan for prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Integr Med. 2017;15(2):77–87. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essa MM, Mohammed A, Guillemin G. The Benefits of Natural Products for Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2016. ISBN:978-3-319-28381-4. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28383-8.

- 8.Zhao HF, Li N, Wang Q, et al. Resveratrol decreases the insoluble Aβ1-42 level in hippocampus and protects the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in AD rats. Neuroscience. 2015;310:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox KHM, Pipingas A, Scholey AB. Investigation of the effects of solid lipid curcumin on cognition and mood in a healthy older population. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:642–651. doi: 10.1177/0269881114552744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saad MA, Abdel Salam RM, Kenawy SA, et al. Pinocembrin attenuates hippocampal inflammation, oxidative perturbations and apoptosis in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Gawryluk JW, Wagener JF, et al. Caffeine blocks disruption of blood brain barrier in a rabbit model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner GZ, Yeung A, Liu JX, et al. The effect of Sailuotong (SLT) on neurocognitive and cardiovascular function in healthy adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled crossover pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-0989-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed HH, Salem AM, Sabry GM, et al. Possible therapeutic uses of Salvia Triloba and Piper nigrum in Alzheimer’s disease-induced rats. J Med Food. 2013;16:437–446. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ou H-C, Song T-Y, Yeh Y-C, et al. EGCG protects against oxidized LDL-induced endothelial dysfunction by inhibiting LOX-1-mediated signalling. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:1745–1756. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00879.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu H, Lui WT, Chu CY, et al. Anti-angiogenic effects of green tea catechin on an experimental endometriosis mouse model. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:608–618. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn HY, Xu Y, Davidge ST. Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate inhibits TNFα-induced monocyte chemotactic protein-1 production from vascular endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2008;82:964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H, Bae JH, Lee S-R. Protective effect of green tea polyphenol EGCG against neuronal damage and brain edema after unilateral cerebral ischemia in gerbils. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:892–900. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh M, Arseneault M, Sanderson T, et al. Challenges for research on polyphenols from foods in Alzheimer’s disease: bioavailability,metabolism, and cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:4855–4873. doi: 10.1021/jf0735073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YJ, Choi DY, Yun YP, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents systemic inflammation-induced memory deficiency and amyloidogenesis via its anti-neuroinflammatory properties. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CL, Chen TF, Chiu MJ, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) suppresses beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting c-Abl/FE65 nuclear translocation and GSK3 beta activation. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JY. Nucleo-cytoplasmic communication in apoptotic response to genotoxic and inflammatory stress. Cell Res. 2005;15:43–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha S, Lieberburg I. Cellular mechanisms of beta-amyloid production and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11049–11053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng-Chung Wei J, Huang HC, Chen WJ, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates amyloid β-induced inflammation and neurotoxicity in EOC 13.31 microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;770:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rezai-Zadeh K, Shytle D, Sun N, et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloidosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8807–8814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1521-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehrnhoefer DE, Bieschke J, Boeddrich A, et al. EGCG redirects amyloidogenic polypeptides into unstructured, off-pathway oligomers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bieschke J, Russ J, Friedrich RP, et al. EGCG remodels mature α-synuclein and amyloid-β fibrils and reduces cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7710–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910723107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chesser AS, Ganeshan V, Yang J, Johnson GV. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances clearance of phosphorylated tau in primary neurons. Nutr Neurosci. 2016;19(1):21–31. doi: 10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang X, Rong C, Chen Y, et al. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuates cognitive deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease model mice by upregulating neprilysin expression. Exp Cell Res. 2015;334(1):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang ZX, Li YB, Zhao RP. Epigallocatechin Gallate attenuates β-Amyloid generation and oxidative stress involvement of PPARγ in N2a/APP695 cells. Neurochem Res. 2017;42(2):468–480. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-2093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezai-Zadeh K, Arendash GW, Hou H, Fernandez F, Jensen M, Runfeldt M, Shytle RD, Tan J. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces beta-amyloid mediated cognitive impairment and modulates tau pathology in Alzheimer transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2008;1214:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Gordon M, Tan J, et al. Oral administration of green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces amyloid beta deposition in transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:576. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith A, Giunta B, Bickford PC, Fountain M, Tan J, Shytle RD. Nanolipidic particles improve the bioavailability and alpha-secretase inducing ability of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Pharm. 2010;389(1–2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giunta B, Hou H, Zhu Y, Salemi J, Ruscin A, Shytle RD, Tan J. Fish oil enhances anti-amyloidogenic properties of green tea EGCG in Tg2576 mice. Neurosci Lett. 2010;471(3):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biasibetti R, Tramontina AC, Costa AP, Dutra MF, Quincozes-Santos A, Nardin P, et al. Green tea (−)epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverses oxidative stress and reduces acetylcholinesterase activity in a streptozotocin-induced model of dementia. Behav Brain Res. 2013;236:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He M, Liu MY, Wang S, Tang QS, Yao WF, Zhao HS, Wei MJ. Research on EGCG improving the degenerative changes of the brain in AD model mice induced with chemical drugs (article in Chinese) Zhong Yao Cai. 2012;35(10):1641–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de la Monte SM. Brain insulin resistance and deficiency as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:35–66. doi: 10.2174/156720512799015037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jia N, Han K, Kong JJ, Zhang XM, Sha S, Ren GR, Cao YP. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates spatial memory impairment in APP/PS1 mice by restoring IRS-1 signaling defects in the hippocampus. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;380(1–2):211–218. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali B, Jamal QM, Shams S, et al. In silico analysis of green tea polyphenols as inhibitors of AChE and BChE enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2016;15:624–628. doi: 10.2174/1871527315666160321110607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mähler A, Mandel S, Lorenz M, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate: a useful, effective and safe clinical approach for targeted prevention and individualised treatment of neurological diseases? EPMA J. 2013;4(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bimonte S, Leongito M, Barbieri A, Del Vecchio V, Barbieri M, AlbinoV, et al. Inhibitory effect of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and bleomycin on human pancreatic cancer MiaPaca-2 cell growth. Infect Agent Cancer. 2015;10:22. doi: 10.1186/s13027-015-0016-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakagawa K, Miyazawa T. Absorption and distribution of tea catechin, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, in the rat. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1997;43:679–684. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.43.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suganuma M, Okabe S, Oniyama M, Tada Y, Ito H, Fujiki H. Wide distribution of [3H](−)-epigallocatechin gallate, a cancer preventive tea polyphenol, in mouse tissue. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1771–1776. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.10.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu L, Zhang QL, Zhang XY, Lv C, Li J, Yuan Y, Yin FX. Pharmacokinetics and blood–brain barrier penetration of (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin in rats by microdialysis sampling coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography with chemiluminescence detection. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:9377–9383. doi: 10.1021/jf301787f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mandel SA, Amit T, Weinreb O, Youdim MB. Understanding the broad-spectrum neuroprotective action profile of green tea polyphenols in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:187–208. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szarc vel Szic K, Declerck K, Vidaković M, Vanden Berghe W. From inflammaging to healthy aging by dietary lifestyle choices: is epigenetics the key to personalized nutrition? Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:33. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, Ohmori K, Shimazu T, Matsui T, Ebihara S, et al. Green tea consumption and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study from the Tsurugaya project 1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:355–361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molino S, Dossena M, Buonocore D, Ferrari F, Venturini L, Ricevuti G, et al. Polyphenols in dementia: from molecular basis to clinical trials. Life Sci. 2016;161:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Einöther SJ, Martens VE. Acute effects of tea consumption on attention and mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(6 Suppl):1700S–1708S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camfield DA, Stough C, Farrimond J, Scholey AB. Acute effects of tea constituents L-theanine, caffeine, and epigallocatechin gallate on cognitive function and mood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(8):507–522. doi: 10.1111/nure.12120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wightman EL, Haskell CF, Forster JS, Veasey RC, Kennedy DO. Epigallocatechin gallate, cerebral blood flow parameters, cognitive performance and mood in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover investigation. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(2):177–186. doi: 10.1002/hup.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scholey A, Downey LA, Ciorciari J, Pipingas A, Nolidin K, Finn M, et al. Acute neurocognitive effects of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) Appetite. 2012;58:767–770. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ide K, Yamada H, Takuma N, Park M, Wakamiya N, Nakase J, et al. Green tea consumption affects cognitive dysfunction in the elderly: a pilot study. Nutrients. 2014;6(10):4032–4042. doi: 10.3390/nu6104032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedemann P. Sunphenon EGCg (Epigallocatechin-Gallate) in the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease - NCT00951834 2009. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00951834.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.