Abstract

Ts1 toxin is a protein found in the venom of the Brazilian scorpion Tityus serrulatus. Ts1 binds to the domain II voltage sensor in the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav and modifies its voltage dependence. In the work reported here, we established an efficient total chemical synthesis of the Ts1 protein using modern chemical ligation methods and demonstrated that it was fully active in modifying the voltage dependence of the rat skeletal muscle voltage-gated sodium channel rNav1.4 expressed in oocytes. Total synthesis combined with click chemistry was used to label the Ts1 protein molecule with the fluorescent dyes Alexa-Fluor 488 and Bodipy. Dye-labeled Ts1 proteins retained their optical properties and bound to and modified the voltage dependence of the sodium channel Nav. Because of the highly specific binding of Ts1 toxin to Nav, successful chemical synthesis and labeling of Ts1 toxin provides an important tool for biophysical studies, histochemical studies, and opto-pharmacological studies of the Nav protein.

Keywords: Ts1 Toxin, voltage-gated Nav channel, chemical protein synthesis, fluorescent dye label, click chemistry

Graphical abstract

Total chemical synthesis of the Ts1 protein was established using modern chemical ligation methods. Click chemistry was used to site-specifically label the synthetic Ts1 protein molecule with fluorescent dyes. Dye-labeled Ts1 protein bound to the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav and modified its voltage dependence in typical fashion.

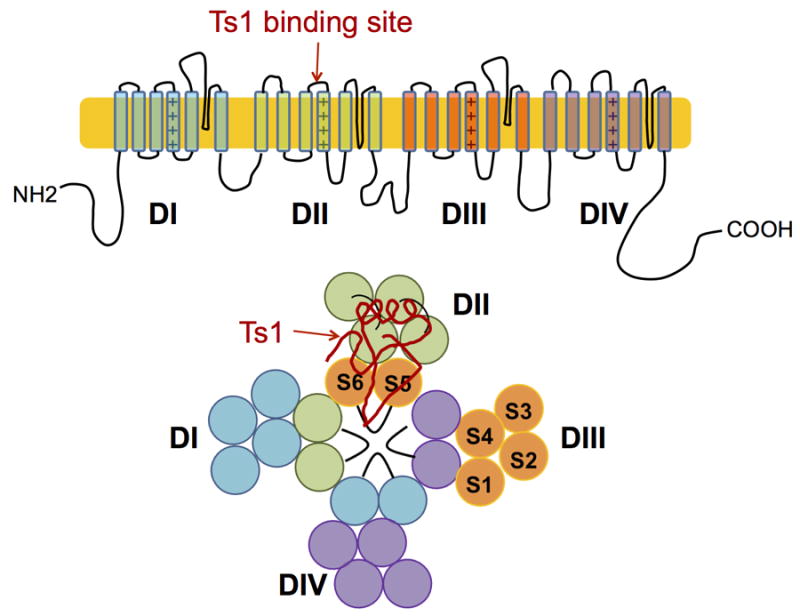

Voltage-gated ion channels play important roles in excitable cells including neurons, cardiac muscle cells and skeletal muscle cells. Voltage-gated sodium ion channels (Nav) are fundamental for the generation and propagation of action potentials. Nav forms the rising phase of the action potential by its rapid opening and contributes partly to repolarization by its inactivation.[1] The Nav channel is composed of a single α subunit and several auxiliary β subunits. The α subunit is a single polypeptide chain made up of four domains (DI-DIV) which form the ion selective pore. Each of the domains (DI-DIV) carries a voltage-sensor domain (VSD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cartoon representation of the α subunit of Nav. The Ts1 toxin protein molecule binds to the voltage-sensor domain (VSD) of DII; a hypothetical binding mode of Ts1 is shown.

Many natural toxins that bind to the Nav channel have been investigated and pharmacological studies have identified functions such as pore-blocking and/or modification of voltage gating.[2] Beta-scorpion toxins are classified as gating modifier toxins. They increase Na+ currents by shifting the threshold of Nav activation in the hyperpolarized direction by more than 20 mV.[3-7] The biophysical mechanism of β-scorpion toxins has been proposed as “VSD trapping” in which the toxin binds to the Domain II VSD and holds that VSD in the activated state.[4,6-7] This was determined by site-directed fluorimetry and gating current measurements by Campos et al.[3]

The neurotoxin protein Ts1 is a β-scorpion toxin and was originally isolated from the venom of the Brazilian scorpion Tityus serrulatus.[8] Ts1 is one of the most potent ligands for both mammalian and insect Nav sodium channels. Because Ts1 locks the Nav channel in the activated state, it would be useful to have fluorescently labeled Ts1 protein(s) to use as biophysical probes for the alterations of Nav channel geometry during activation. Such probes need to be labeled at single sites within the Ts1 protein molecule, the fluorescent dyes must retain their optical properties, and the labeled Ts1 must retain native channel gating modifying activity. Here we report the total chemical synthesis of biologically active Ts1, and the preparation of two site-specifically labeled fluroescent Ts1 protein molecules that retain channel gating modifying activity.

The Ts1 toxin protein has a polypeptide chain of 61 amino acid residues with 8 cysteines that form 4 disulfide bonds (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Amino acid sequence of Ts1 toxin. (b) Connectivity of the disulfide bonds in the Ts1 toxin.[11]

There are conflicting published reports of the chemical nature of the C-terminus of Ts1 toxin. According to the two crystal structures of Ts1 isolated from scorpion venom,[9,10] the C-terminal of Ts1 toxin is a carboxyl group. However, in the paper that reported the original determination of the amino acid sequence of Ts1 toxin,[11] the C-terminus was reported to be a carboxamide. Analysis of the gene sequence supported the assignment of the C-terminus as a carboxamide.[12] To resolve the question of the chemical identity of the C-terminal of the Ts1 protein molecule, we decided to synthesize both the Ts1.COOH and Ts1.CONH2. The total syntheses of Ts1.COOH and Ts1.CONH2 were carried out by the native chemical ligation of unprotected peptide segments,[13] as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Native chemical ligation-based modular synthetic strategies for: (a) Ts1.COOH (b) Ts1.CONH2

Native chemical ligation sites were chosen at −Tyr22 −Cys23− and −Ala41− Cys42− so that the peptide segments have approximately the same length. Peptides were prepared by in situ neutralization Boc chemistry solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS),[14] then purified by reverse phase HPLC and chracterized by LCMS. For the synthesis of the Ts1.COOH polypeptide chain, the three peptide segments were condensed by the one-pot method.[15] Peptide [Trp(CHO)39]Thz23-Ala41-COSR was first reacted with peptide Cys42-Cys61.COOH to form product [Trp(CHO)39]Thz23-Cys61.COOH. Then N-terminal residue Thz23 was converted to Cys23 by addition of MeONH2·HCl at pH 4. After readjustment of the reaction mixture to pH 7.0, peptide Lys1-Tyr22-COSR was added for the second ligaton reaction. Finally, the Trp39 side chain formyl protecting group was removed by addition of piperidine. The full length Ts1 Lys1-Cys61.COOH product was isolated by preparative HPLC purification. Analytical data for the synthesis are shown in the Supporting Information.

For the synthesis of the Ts1.CONH2 polypeptide chain, peptide Cys42-Cys61.CONH2 was prepared by reaction of peptide [Trp(CHO)50,54]Thz42-Lys60-COSR with Cys61-CONH2, followed by conversion of the Thz- to Cys- and removal of the formyl protecting groups. The one pot synthesis data are given in the Supporting Information. The versatility of the modular synthetic strategy used for the total synthesis of the full length Ts1 polypeptide chain is evident from the ease with which both C-terminal forms of Ts1 were prepared, and will be useful for the synthesis of Ts1 analogs in the future.

Folding of the purified Ts1 polypeptide chains was initially carried out under conventional conditions that used a redox couple and a low concentration of a chaotrope, Gu·HCl, to keep misfolded/mispaired disulfide intermediates in solution: 100 mM Tris, 0.5mM GuHCl, 8 mM cysteine and 1 mM cystine, polypeptide 0.5 mg/mL, pH 8.0, room temperature. However, this approach failed. Alternative folding conditions were then screened by varying polypeptide concentration, temperature, cysteine/cystine ratio, and pH; also by using a GSSG/GSH redox system, or by using air oxidation. When the folding reaction was performed at 4°C, and at low polypeptide concentration, yields improved (Figure S7). The best folding conditions found were: 0.5 M Gu·HCl, 100 mM Tris, pH 8, 1mM Cystine·2HCl, 8 mM Cysteine, Ts1.COOH polypeptide 0.01 mg/mL, 4 °C. These conditions were used to fold both Ts1.COOH and Ts1.CONH2; the purified products are shown in Figure 3.

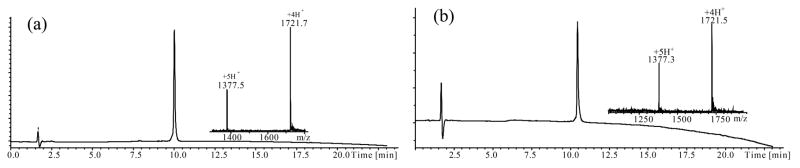

Figure 3.

Analytical LCMS data for the synthetic toxins. (a) Purified folded Ts1.COOH toxin. [Inset] ESMS data. Obsd 6882.7 ± 0.5 Da; Calc 6882.9 Da (av. isotopes); (b) Purified folded Ts1.CONH2 toxin.[Inset] ESMS data. Obsd 6881.8 ± 0.5 Da; Calc 6881.9 Da (av. isotopes). The MS data shown were collected across the entire UV absorbing peak in each chromatogram.Both the folded Ts1.COOH and Ts1.CONH2 protein molecules have masses 8 Da less than the corresponding reduced polypeptides, indicating the formation of 4 disulfide bonds.

Potencies of the folded synthetic proteins were evaluated using rat skeletal muscle voltage-gated sodium channel (rNav1.4) expressed in oocyte’s membrane, by the Cut-open Oocyte Voltage Clamp (COVC) technique (Figure 4).[16] In the absence of toxin the activation threshold of the rNav1.4 channel was approximately - 43 to - 44 mV. In the presence of 72 nM Ts1.COOH, the threshold was approximately - 60 mV; i.e. the activation threshold was shifted by 16 to 17 mV. This result indicated that Ts1.COOH is active as a modifier of the voltage dependence, but the extent of shift was smaller than the data previously reported for similar measurements using natural Ts1-toxin purified from scorpion venom.[3] In the presence of 72 nM Ts1.CONH2, the activation threshold was approximately - 66 to -67 mV; i.e. the activation threshold was shifted by 22 to 24 mV. This magnitude of shift of the activation threshold was comparable to the maximum effect exerted by the natural Ts1 toxin as reported previously.[3] These results showed that the synthetic Ts1.CONH2 protein amide has similar potency to the natural Ts1 toxin. LCMS analysis of natural Ts1 toxin purified from scorpion venom showed that the natural Ts1 toxin has the same mass as synthetic Ts1.CONH2 (Figure S8). Thus, the activity data and mass measurements confirmed that the natural Ts1 toxin is a C-terminal amide.[11]

Figure 4.

Synthetic Ts1-toxins activities. Voltage-dependence of rNav1.4 conductance in the absence of toxin (black circles) and in the presence of 72 nM Ts1.COOH (red squares) and in the presence of 72 nM Ts1.CONH2 (blue squares). Left: Normalized conductance vs. voltage. Right: enlargement of the threshold voltage region in the range -70 mV to -40 mV. The dash-dotted line indicates 0.1 % of the conductance. The double asterisks indicate statistical significance where p is < 0.01; single asterisk is p < 0.05. The “n” indicates the number of data tested. Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM).

Our next step was to label the Ts1.CONH2 protein molecule with fluorescent dyes. We chose side chains on the face of the protein molecule remote from residues believed to be involved in the binding of Ts1 to the sodium channel. In our initial attempts, residues Trp50 and His8 were changed to cysteines. Then the Bodipy dye was attached at either Cys50 or Cys8 in the course of the synthesis, to give the site-specifically labeled Ts1 polypeptides [W50C(Bodipy)]Ts1.CONH2 and [H8C(Bodipy)]Ts1.CONH2. We were unable to fold either of these pre-labeled polypeptide chains. Next we tried to fold the Ts1 polypeptides with an extra Cys, then label the folded molecules. We made the two polypeptide chains [W50C]Ts1.CONH2 and [H8C]Ts1.CONH2, but we were able to fold only [H8C]Ts1.CONH2, which was then labeled with Bodipy and Rodamine. However, neither of these labeled Ts1 proteins showed any channel modifying activity.

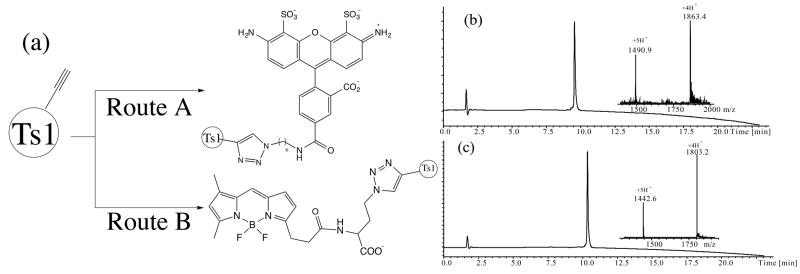

To overcome the challenge of site-specific dye labeling of the Ts1 protein while retaining channel modifying activity, we explored the use of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition chemistry.[17-20] In this case, Trp50 was replaced by L-propargylglycine (Pra50). This Ts1 analogue was prepared by the same modular synthetic strategy used for the Ts1.CONH2 synthesis, as shown in Scheme 1(b). The propargylglycine–containing polypeptide chain was folded under the same conditions used to fold Ts1.CONH2 (Figure S10). Then the [W50Pra]Ts1.CONH2 was reacted with different azido-dyes using Cu(I) catalysis. After optimization, the best labeling reaction conditions were: 1.0 M Gu·HCl, 0.2 M Tris, 40 mM TCEP, 80 mM CuSO4, pH 8.5, [W50Pra]Ts1.CONH2 37.0μM, azido-Dye 92.5 μM, room temperature. The Ts1 protein was labeled with azido-AlexaFluor 488 (route A in Figure 5(a)) and γ-Azido-L-Abu-Bodipy (route B in Figure 5(a)); each of the labeled products was purified after the labeling reaction was over (Figure 5(b), (c)). We also evaluated the absorption and emission spectra of Ts1-Alexa and Ts1-Bodipy (Figure S11). These fluorescently labeled Ts1 proteins showed similar absorption and emission spectra to the dye molecules themselves – the optical properties of dyes were unchanged after conjugation to the Ts1 protein molecule.

Figure 5.

Fluroescent labeling of Ts1. (a) Synthetic strategy. (b) [W50Pra]Ts1.CONH2 labeled with alexa-488. [Inset] ESMS data: Mass (obsd) 7449.6 ± 0.5 Da; calc 7449.5 Da. (c) [W50Pra]Ts-.CONH2 labeled with Bodipy. [Inset] ESMS data: Mass (obsd) 7208.4 ± 0.5 Da; calc 7209.0 Da. The MS data shown in panels (b) and (c) were collected across the entire UV absorbing peak in each chromatogram.

The channel modifying activities of the dye-labeled Ts1 proteins were characterized by using the COVC technique (Figure 6).[16] At 150 nM Ts1-Alexa, the conductance versus applied voltage was similar to the conductance observed using 72 nM Ts1.CONH2 (although the conductance of Ts1-Alexa was higher than that of Ts1.CONH2 at both the -50 mV and -45 mV data points). This result indicated that 150 nM Ts1-Alexa had the approximately the same potency as 72 nM Ts1.CONH2. On the other hand, at 200 nM Ts1-Bodipy the conductance was similar to the conductance observed in the presence of 72 nM Ts1.CONH2 over the range from -60 mV to -35 mV, although the threshold in the presence of 200 nM Ts1-Bodiopy seemed to be slightly higher. Above -30 mV, the conductance in the presence of 200 nM Ts1-Bodipy was lower than for 72 nM Ts1.CONH2.

Figure 6.

Assay of Ts1-dye conjugates by COVC technique. Voltage dependence of conductance of rNav1.4 in the presence of 72 nM Ts1.CONH2 (blue squares), 150nM Ts1-Alexa (magenta squares) and 200nM Ts1-Bodipy (green squares). Left: Normalized conductance vs.voltage. Right: Enlarged activation of the threshold region, -70 mV to –40 mV. The dash-dotted line indicates 0.1 % of conductance. The single asterisk indicates the statistical significance with p <0.05. The “n” indicates the number of data tested. Error bars indicate Standard Error of the Mean (SEM).

This observation indicated 200 nM Ts1-bodipy had almost the same potency as 72 nM Ts1.CONH2. Taken together, our Ts1-dye conjugates were active channel modifying proteins with 2-3 times less potency than native Ts1. An AlexaFluor 488 dye-labeled Ts1 analogue in which His8 was replaced by Pra8 was also synthesized, but the final product was not as active as the Trp50Pra analogues (data not shown).

In conclusion, we have established a modular total chemical synthesis of Ts1 toxin using native chemical ligation of unprotected peptide segments combined with folding at high dilution in the presence of a redox couple. Our synthetic Ts1.CONH2 was equally as potent as the natural Ts1 in modifying the activation threshold of the voltage gated Nav ion channel. Interestingly, we found that Ts1.COOH was less potent against rNav1.4. However, the molecular mechanism for this potency difference is unknown. By employing click chemistry, we have also established a general way to label the Ts1 protein molecule while retaining its biological activity. Both synthetic Ts1-Alexa and Ts1-Bodipy have potency only 2-3 times less than Ts1.CONH2 and maintain the optical properties of the dyes themselves. The ability to site-specifically label the Ts1 protein molecule with fluroescent dyes while retaining its acitivity provides us with a powerful tool for the biophysical characterization of Nav channels.[21]

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from American Heart Association (13POST14800031) to T.K., by NIH grants GM68044-07 to A.M.C., and U54GM087519 and GM030376 to F.B.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx.

Contributor Information

Bobo Dang, Department of Chemistry, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637.

Dr. Tomoya Kubota, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637.

Prof. Dr. Ana M. Correa, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637

Prof. Dr. Francisco Bezanilla, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637

Prof. Dr Stephen B. H. Kent, Department of Chemistry, Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, University of Chicago Chicago, IL 60637.

References

- 1.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cestele S, Catterall WA. Biochimie. 2000;82:883–892. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)01174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos FV, Chanda B, Beirao PSL, Benzanilla F. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:257–268. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cestele S, Qu Y, Rogers JC, Rochat H, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Neuron. 1998;21:919–931. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcotte P, Chen LQ, Kallen RG, Chahine M. Circ Res. 1997;80:363–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang JZ, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Scheuer T, Karbat I, Cohen L, Gordon D, Gurevitz M, Catterall WA. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:33641–33651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.282509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang JZ, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Scheuer T, Karbat I, Cohen L, Gordon D, Gurevitz M, Catterall WA. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30719–30728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.370742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Possani LD, Martin BM, Mochcamorales J, Svendsen I. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1981;46:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinheiro CB, Marangoni S, Toyama MH, Polikarpov I. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:405–415. doi: 10.1107/s090744490202111x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polikarpov I, Junior MS, Marangoni S, Toyama MH, Teplyakov A. J Biol Chem. 1999;290:175–184. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bechis G, Sampieri F, Yuan PM, Brando T, Martin MF, Diniz CR, Rochat H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;112:1146–1153. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin-Eauclaire MF, Céard B, Ribeiro AM, Diniz CR, Rochat H, Bougis PE. FEBS Lett. 1992;302:220–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80445-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson PE, Miur TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SBH. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnölzer M, Alewood P, Jones A, Alewood D, Kent SBH. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1992;40:180–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bang D, Kent SBH. Angew Chem. 2004;116:2588–2592. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2534–2538. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefani E, Bezanilla F. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:300–318. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toenøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M. J Org Chem. 2002;67:3057–3064. doi: 10.1021/jo011148j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee D, Mandal K, Harris PWR, Brimble MA, Kent SBH. Org Lett. 2009;11:5270–5273. doi: 10.1021/ol902131n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Chan TR, Hilgraf R, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB, Finn MG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3192–3193. doi: 10.1021/ja021381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandtner W, Bezanilla F, Correa AM. Biophys J. 2007;93:L45–47. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.