Abstract

Isotope-edited two-dimensional Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (2D FTIR) can potentially provide a unique probe of protein structure and dynamics. However, general methods for the site-specific incorporation of stable 13C=18O labels into the polypeptide backbone of the protein molecule have not yet been established. Here we describe, as a prototype for the incorporation of specific arrays of isotope labels, the total chemical synthesis – via a key ester insulin intermediate – of 97% enriched [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin, stable-isotope labeled at a single backbone amide carbonyl. The amino acid sequence as well as the positions of the disulfide bonds and the correctly folded structure were unambiguously confirmed by the X-ray crystal structure of the synthetic protein molecule. In vitro assays of the isotope labeled [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin showed that it had full insulin receptor binding activity. Linear and 2D IR spectra revealed a distinct red-shifted amide I carbonyl band peak at 1595 cm−1 resulting from the (1-13C=18O)PheB24 backbone label. This work illustrates the utility of chemical synthesis to enable the application of advanced physical methods for the elucidation of the molecular basis of protein function.

Keywords: human insulin, chemical protein synthesis, native chemical ligation, isotope labeling, 2D IR spectra

Entry for the Table of Contents

Just one carbonyl, please. Human insulin was specifically labeled at the (1-13C=18O)PheB24 single backbone carbonyl, by total chemical synthesis via a key ester insulin intermediate. The synthetic protein was characterized by X-ray crystallography and had full insulin receptor-binding activity. Linear and 2D IR spectra of isotope-labeled human insulin revealed a distinct spectral peak at 1595 cm−1, a red shifted amide I band from the (1-13C=18O)PheB24 label.

Two-dimensional Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (2D FTIR) is emerging as a powerful technique for the study of the transient structures and dynamics of protein molecules.[1] Most importantly, 2D FTIR makes use of backbone amide I vibrations to reveal protein secondary structure and to probe H-bonding interactions.[2] Because even small protein molecules have dozens of backbone amides with similar vibrational properties, it is essential to make use of 13C=18O double isotope labeling of the carbonyls at specific peptide bonds, in order to isolate vibrational signals from the region(s) of interest in the protein molecule.[2–3] Over the past decade, chemical synthesis of peptides with site-specific 13C=18O backbone amide labels as 2D FTIR probes has provided information ranging from structural studies of model peptides[4] to the role of water in a homotetrameric proton channel.[5] The research community seeks to extend such isotope-edited FTIR studies to more complex protein molecules.[1, 6] However, with rare exceptions,[7] residue-specific isotope labeling has been limited to small protein domains that are directly accessible by stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS). There is a need for a general method for 13C=18O labeling peptide bond carbonyls at one or more specific sites in the backbone of a protein molecule. In the work reported here, we describe the application of total chemical synthesis to the site-specific stable isotope labeling of a protein molecule. The methods described can be used to specifically label any region of the molecule being studied, and will be applicable to a wide range of proteins.

Human insulin is a protein hormone that plays a key role in energy metabolism.[8] The mature human insulin protein molecule consists of two polypeptide chains, the 21 amino acid residue A chain and the 30 amino acid residue B chain, with two inter-chain and one intra-chain covalent disulfide bonds (Figure 1).[9] A key aspect of the biosynthesis and storage of human insulin is the formation of insulin dimers, which coordinate zinc ions to form zinc-containing hexamers that in turn form aggregates in the beta-cells of the pancreas.[10] These secretory granules are the principal storage form of insulin, from which it is released into the circulation. As part of a research project to study the monomer-dimer equilibrium of the human insulin protein molecule using time-resolved 2D infrared spectroscopy,[11] we set out to prepare human insulin labeled with stable-isotope reporter nuclei at a single backbone carbonyl in the insulin dimer interface. The carbonyl group of residue PheB24 is involved in critical H-bonding interactions across the PheB24-TyrB26 β-sheet interface in human insulin dimers.[11] We wanted to 13C=18O label the backbone carbonyl of PheB24 alone in the 51 amino acid residue human insulin protein molecule, in order to be able to use 2D FTIR to probe key aspects of the monomer-dimer equilibrium of this important protein molecule.

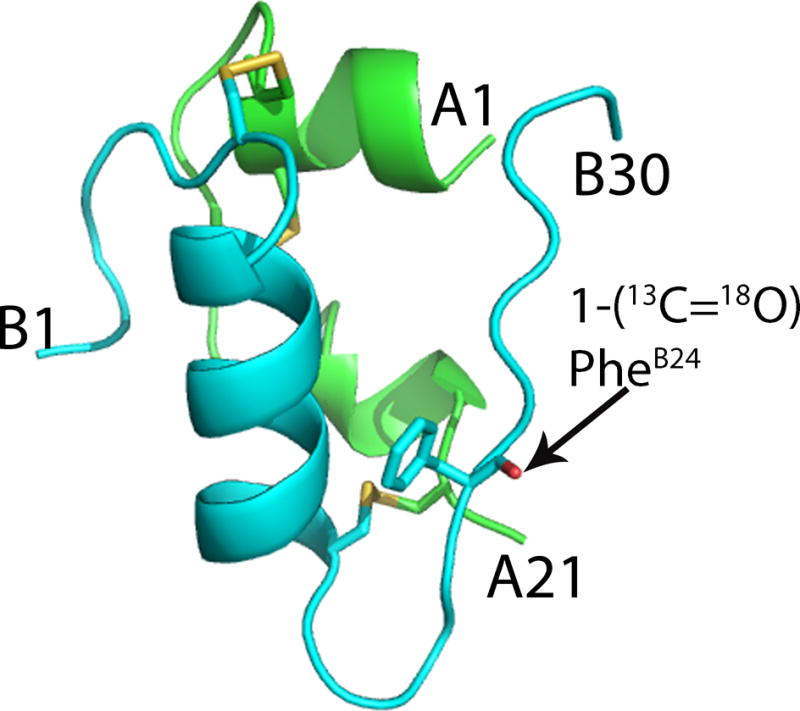

Figure 1.

Covalent structure of the human insulin protein molecule. The amino acid sequences of the 21 residue A chain and 30 residue B chain are given using the single letter code. Stable-isotope labeled residue PheB24 is highlighted in red.

Human insulin is a notoriously difficult target for total chemical synthesis.[12] Synthesis and handling of the individual 21 residue A and 30 residue B peptide chains is itself challenging,[12b] and efficient formation of the folded insulin protein molecule can only be achieved by the use of orthogonally protected cysteine residue side chains and directed disulfide formation.[13] We recently reported a simple and efficient route to the total chemical synthesis of DKP insulin, a form of insulin that is monomeric because of the replacement of HisB10 by AspB10 and that has substantially reduced aggregation properties because of the inversion of the –ProB28-LysB29– sequence.[14] This efficient total synthesis proceeded via a 51 residue depsipeptide that folds efficiently to give ‘ester insulin’, which can be readily converted to fully active DKP insulin.[15] The ester insulin approach has not been applied to the total synthesis of human insulin.

Here we describe the preparation of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin by one-pot native chemical ligation[16] of three unprotected synthetic peptide segments [Scheme 1]. This synthetic strategy was based on that previously used for the synthesis of monomeric DKP insulin, which protein was designed to have optimal handling characteristics.[15b] In the case of human insulin, peptide chain aggregation and the formation of protein oligomers make this a substantially more challenging synthetic target and total synthesis by the ester insulin route required significant optimization.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin.

Details of the synthesis were as follows. The (1-13C=18O)PheB24 labeled depsipeptide GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1 was synthesized at a 0.2 mmol scale on Boc-Cys-SCH2CO-Ala-OCH2-Pam-resin, using manual Boc chemistry in situ neutralization SPPS protocols (Scheme 2). The orthogonally protected ester-linked dipeptide Boc-GluA4[Oβ(Alloc-L-ThrB30-α-OcHex)]-OH was used in the synthesis of the N-benzyloxycarbonyl-GlyA1-CysA6 sequence, then the Alloc protecting group was removed and the ThzB19-ThrB30 sequence was assembled in stepwise fashion.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of the stable-isotope labeled segment GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1 by solid phase peptide synthesis. Conditions: i) Boc-Ala-OCH2Ph-CH2COOH, DIC, DCM; ii) a) TFA, b) Trt-SCH2COOH, HBTU, DIEA, DMF; iii) a) TFA/TIPS/water (95:2.5:2.5 v/v), b) BocAA-OH, HBTU, DIEA, DMF (SPPS, 2 cycles); iv) a) TFA, b) Boc-Glu[Oβ(Alloc-L-Thr-α-OcHex)]-OH, HBTU, DIEA; v) a) TFA, BocAA-OH, HBTU, DIEA, DMF (SPPS, 3 cycles); b) TFA followed by 25% DIEA/DMF, 2-Cl-ZOSu, DMF; vi) a) Pd(PPh3)4, PhSiH3, DCM, b) BocAA-OH, HBTU, DIEA, DMF (SPPS, 11 cycles); HF-p-cresol.

Isotope labeled Boc-(1-13C=18O)PheB24 with 97.1% isotope enrichment was prepared as described in the Supporting Information, and efficiently incorporated under conditions that used a minimum amount of the isotope-labeled amino acid: 0.25 mmol, 0.4 M Boc-(1-13C=18O)Phe, 0.23 mmol HBTU, 0.55 mmol DIEA for 1 hr. The isotope-labeled depsipeptide-thioester was deprotected and simultaneously cleaved from the resin by treatment with anhydrous HF, purified by preparative reverse phase HPLC, and characterized by LCMS analysis to give GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

[Upper panel] Stable-isotope labeled GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1, R = CH2CO-Ala; [Lower panel] LCMS characterization of 1 after prep-HPLC purification (inset showing the online ESI-MS spectrum taken across the whole UV peak).): observed mass 2195.0 ± 0.2 Da; calculated mass, 2195.0 Da (monoisotopic) and 2195.4 Da (average isotopes).The chromatographic separations were performed on a C4 (2.1×50 mm) column using a linear gradient (5–45%) of solvent B in solvent A over 40 min (solvent A = 0.1% TFA in water, solvent B = 0.08% TFA in acetonitrile).

The peptide CysA7-AsnA21 2 and the peptide PheB1-ValB18-αthioester 3 were synthesized by manual Boc chemistry SPPS using in situ neutralization protocols on Boc-Asn-OCH2-Pam-resin and Boc-Val-SCH2CO-Ala-OCH2-Pam-resin, respectively. Each peptide was cleaved from the resin and simultaneously deprotected by treatment with HF. Removal of the HF-stable DNP group from side chain-protected His residues in peptide 3 was achieved in solution using 50 mM MESNa at pH 7.0, to generate the deprotected peptide-SCH2CH2SO3− thioester. Both unprotected synthetic peptides were purified by preparative reverse phase HPLC and characterized by LCMS analysis (details in Supporting Information).

These three unprotected synthetic peptide segments were used in the preparation of the 51 residue ester insulin polypeptide chain.[15b] The isotope-labeled peptide-thioester segment GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1 was reacted with peptide CysA7-AsnA21 2 by native chemical ligation at pH 7.0. Reaction progress was monitored by analytical LCMS. Once the ligation reaction was complete, the N-terminal ThzB19 was converted to CysB19 by overnight treatment with MeONH2.HCl at pH 4. To the same reaction mixture, after readjustment to pH 7.0, was added PheB1-ValB18-αthioester 3, 50 mM TCEP, and 200 mM MPAA. After the second native chemical ligation reaction was completed, the reaction mixture was diluted ten-fold with water, causing the product full length 51 residue isotope-labeled depsipeptide chain to precipitate. Crude full length polypeptide chain GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-PheB1]-GlnA5-AsnA21 6 was isolated by centrifugation (see Supporting Information).

Without further purification, the lyophilized crude full length polypeptide 6 was folded at near-physiological pH 7.6 under the following conditions: 1.5 M GuHCl, 8 mM cysteine/1 mM cystine redox couple, 20 mM Tris at a polypeptide concentration of 0.05 mg/mL. Folding with concomitant formation of three disulfide bonds was essentially complete within 2 hours as indicated by the appearance of a sharper, earlier eluting peak in LCMS, and a decrease in the observed mass of 5.5 ± 0.8 Da (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Folding stable-isotope labeled ester insulin, with concomitant formation of disulfide bonds. a) HPLC-traces showing the folding reaction at, t = 0 h and t = 2 h. Conditions: aqueous buffer containing 1.5 M GuHCl, 20 mM Tris, 8 mM Cysteine and 1 mM Cystine.HCl, pH 7.6, polypeptide concentration: 0.05 mg/mL; b) LC-MS data for the purified folded (1-13C=18O)PheB24 labeled human ester insulin (inset showing the online ESI-MS spectra taken across the whole of the main UV peak, and observed mass). The chromatographic separations were as described in Figure 2.

Folded isotope-labeled ester insulin was subjected to controlled saponification using 25 mM LiOH in water at pH 12.2 and 4 °C, at a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. We saw improved reaction rate and yield when the reaction was carried out in water, rather than the mixed aqueous-organic solvent previously used.[15] The reaction was essentially complete after 6 hrs (Figure 4 (a)). Trace amounts of oxidized B chain were formed under these experimental conditions, eluting just before the desired product. Then the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 3 and the isotope-labeled human insulin was purified by preparative reverse phase HPLC and characterized by LCMS (Figure 4 (b)): observed mass 5810.4 ± 0.6 Da; calculated mass for the isotope-labeled peptide 5810.6 Da (average isotope composition, + 3.0 Da for labeled 13C=18O atoms).

Figure 4.

Saponification of isotope-labeled ester insulin to give [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin. Reaction was carried out in 25 mM LiOH in water at pH 12.2 and 4 °C. a) HPLC profiles showing the progress of the reaction as a function of time; b) LC-MS data for the [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin after HPLC purification (inset showing the online ESI-MS spectra across the whole of the UV absorbing peak). Reverse phase HPLC under the same conditions as for Figure 3. (Bottom panel) High resolution direct infusion ESI-MS spectra of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin M+4H+ m/z region. Inset showing the monoisotope regions from [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin and [(1-13C=16O)PheB24]human insulin. The ratio between those two peaks was 96.7% which corresponds closely to the (1-13C=18O)PheB24 isotope enrichment in the final protein molecule.

Key aspects of the synthesis of the human insulin isotopologue were as follows. Initial attempts to carry out isotope exchange reaction of Boc-(1-13C)Phe-OH with H218O were not fruitful when we followed a previously reported protocol for the efficient 18O isotope exchange of Nα-protected amino acids.[17] We then carried out the Boc-protection/isotope exchange reaction in the reverse order. First, we conducted the exchange reaction of H-(1-13C)Phe-OH with a 1:1 mixture of H218O/dioxane at 100 °C;[18] After a few cycles of the exchange reaction, satisfactory enrichment was obtained. Lyophilization followed by Boc-protection in dioxane/water and rapid acid-base extraction workup gave essentially pure Boc-(1-13C=18O)Phe.

Synthesis of the labeled peptide segment GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-PheB24(1-13C=18O)-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester 1 was carried out using Boc chemistry in-situ neutralization SPPS protocols,[19] in order to preserve the thioester moiety. After addition of the ester-linked dipeptide Boc-GluA4[Oβ(Alloc-L-ThrB30-α-OcHex)]-OH with its three orthogonal protecting groups, each removable under distinct conditions (mild acidolysis; reductive cleavage; strong acidolysis), the Boc-group was removed and the remainder of the A-chain sequence was added through residue GlyA1. The N-terminus of GlyA1 was re-protected as 2-Cl-Z, then the Alloc protecting group was removed using Pd(PPh3)4/phenylsilane under argon atmosphere, and the sequence was assembled through PheB25. Amino acid Boc-(1-13C=18O)PheB24 was incorporated using modified coupling conditions to minimize the amount of valuable labeled amino acid used. Then the synthesis was continued through the coupling of ThzB19, which was used as a cryptic form of N-terminal Cys[20] to prevent undesired intramolecular cyclization. [21]

Covalent condensation of the three unprotected peptide segments PheB1-ValB18-αthioester, GlyA1-GluA4[OβThrB30-(1-13C=18O)PheB24-ThzB19]-CysA6-αthioester, and CysA7-AsnA21 in a series of one-pot reactions was straightforward, and was carried out without isolation/purification of intermediate products. The linear 51-residue ester linked depsipeptide thus obtained was precipitated by addition of water and the partially-purified product was folded using a cysteine/cystine redox couple at pH 7.6 at a polypeptide concentration of 0.05 mg/mL. Attempts to carry out the folding at higher polypeptide concentrations of 0.3 mg/mL and 0.1 mg/mL gave poor yields of the folded ester insulin. A product eluting as a much earlier, sharper peak on analytical reverse phase HPLC together with a decrease in mass of 5.5 ± 0.8 Da was consistent with the formation of a folded ester insulin protein molecule containing three disulfide bonds. The overall yield of ester insulin based on limiting thioester peptide 1 was 25% (20 mg ester insulin was obtained from 80 mg of partially purified polypeptide). Saponification of ester insulin to form the native insulin protein molecule gave a somewhat later eluting peak that had an 18 Da mass increase, indicative of addition of the elements of water. The reaction proceeded smoothly and gave a 63% isolated yield (7.6 mg insulin from 12 mg of ester insulin). High resolution direct-infusion ESI MS of the purified isotope-labeled synthetic protein gave an observed monoisotopic mass of 5806.641 ± 0.003 Da (theoretical monoisotopic mass: 5806.645 Da).

High resolution direct infusion ESI mass spectrometry data of the purified synthetic [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin was also used to establish the 18O-labeling efficiency in the final insulin protein molecule (Figure 4, bottom panel). This was to see if there is any significant decrease in the degree of 18O-labeling in the final labeled protein synthetic product arising from chemical manipulations such as amino acid coupling conditions, acid treatment during Boc removals, and especially during final saponification with LiOH in water, which could lead to oxygen exchange and lower the enrichment. Analysis of the monoisotopic region revealed two distinct peaks at m/z 1452.1671 ± 0.0008 and 1452.6681 ± 0.0008 for the M+4H+ charge states of synthetic [(1-13C=16O)PheB24]human insulin (Theoretical monoisotopic M+4H+ m/z 1452.1681) and [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin (Theoretical monoisotopic M+4H+ m/z 1452.6692) respectively. Using the ratio between these two peaks the 18O enrichment was found to be 96.7%, which is in excellent agreement with the measured 97.1% enrichment of the starting (1-13C=18O)Phe amino acid (see Supporting Information), showing that within experimental error there was no loss of 18O during the chemical manipulations involved in the synthesis.

The crystal structure of purified [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin at a resolution of 1.25Å unambiguously confirmed the amino acid sequence, the covalent structure including disulfide bonds, and the correctly folded tertiary structure of the synthetic protein molecule (Figure 5).[22].

Figure 5.

X-ray crystal structure of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin PDB code 5ENA. Cartoon representations of the A chain (green) and B chain (cyan). Disulfide bonds are shown in yellow. The site of isotope labeling at (1-13C=18O)PheB24 is shown as stick representation (O, red).

Synthetic [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin was assayed for in vitro binding to the human insulin receptor, using wild-type biosynthetic human insulin for comparison (Figure S10). The receptor-binding activity of labeled human insulin was indistinguishable from that of wild-type human insulin within experimental uncertainty.

Finally, to demonstrate that the site-specific backbone bone carbonyl 13C=18O isotope label can be a useful probe of the dimer interface in the insulin self-association process, we performed linear and 2D IR spectroscopy of the [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin protein molecule (Figure 6). Both linear and 2D IR spectra reveal a distinct peak at 1595 cm−1 resulting from the (1-13C=18O)PheB24 label, red shifted from the main amide I band. The peak is clearest for experimental conditions where the dimer population is known to dominate. This peak broadens and decreases in amplitude as the temperature is increased, consistent with solvent exposure of the label as the dimer population decreases.

Figure 6.

FTIR and 2D IR spectra of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin in deuterated solvent at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in phosphate buffer and 20% ethanol at pD 2.0. (A) Linear FTIR spectra for the insulin amide I carbonyl stretch. [Inset: the FTIR difference spectrum of [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin from human insulin for the spectral region of the isotope label] (B) Temperature difference FTIR spectra of the (13C=18O)PheB24 isotope label relative to 55°C; 15° (blue) to 55°C (red). (C) 2D IR spectra at 15°C and (D) 55°C (waiting time of 150 fs).

In the work reported here, we have optimized a convergent route to the total synthesis of human insulin and applied it to the efficient site-specific labeling of the human insulin protein molecule. Ten milligram amounts of site-specifically labeled human insulin were obtained from a lab scale synthesis. The X-ray crystal structure of the synthetic protein molecule unambiguously confirmed its covalent structure, as well as the native disulfide bonds and correctly folded protein structure. The isotope-labeled [(1-13C=18O)PheB24]human insulin was fully active in insulin receptor binding. The single 13C=18O carbonyl was readily distinguished from the main amide I band in 2D FTIR spectra of the labeled protein molecule. In further work, we have prepared ten milligram amounts of the human insulin protein isotopomers individually backbone labeled with 13C=18O at GlyB23 and GlyB8, and a human insulin protein isotopologue double labeled with 13C=18O at both GlyB20 and GlyB23, for 2D FTIR studies of this important protein (data not shown).

Our results demonstrate the versatility and utility of total protein synthesis based on modern chemical ligation methods. The work described here overcomes the size limitations of stepwise SPPS, and will extend site-specific isotope labeling of backbone carbonyls to a wide range of target protein molecules, by total chemical[23] or semi-synthesis.[24] The synthetic approaches used in this work will be useful for the study of a variety of aspects of the molecular basis of function in human insulin and other protein molecules by 2D FTIR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.T. thanks the National Science Foundation (CHE-1414486) for support of this research. Parts of this work were supported by NIH grant R01DK08993 to SBK. Use of NE-CAT beamline 24-ID at the Advanced Photon Source is supported by award RR-15301 from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health. Use of the Advanced Photon Source is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- 1.Le Sueur AL, Horness RE, Thielges MC. Analyst. 2015;140:4336–4349. doi: 10.1039/c5an00558b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baiz CR, Reppert M, Tokmakoff A. Ultrafast Infrared Vibrational Spectroscopy. CRC Press; 2013. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baiz CR, Tokmakoff A. Biophys J. 2015;108:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courter JR, Abdo M, Brown SP, Tucker MJ, Hochstrasser RM, Smith AB. J Org Chem. 2014;79:759–768. doi: 10.1021/jo402680v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh A, Wang J, Moroz YS, Korendovych IV, Zanni M, DeGrado WF, Gai F, Hochstrasser RM. J Chem Phys. 2014;140:235105/1–235105/9. doi: 10.1063/1.4881188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thielges MC, Axup JY, Wong D, Lee HS, Chung JK, Schultz PG, Fayer MD. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:11294–11304. doi: 10.1021/jp206986v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis CM, Cooper AK, Dyer RB. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1758–1766. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonksen P, Sonksen J. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:69–79. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Sanger F. Science. 1959;129:1340–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.129.3359.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nicol DSHW, Smith LF. Nature. 1960;187:483–485. doi: 10.1038/187483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Brader ML, Dunn MF. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90140-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dodson G, Steiner D. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Ganim Z, Jones KC, Tokmakoff A. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:3579–3588. doi: 10.1039/b923515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zoete V, Meuwly M, Karplus M. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2005;61:79–93. doi: 10.1002/prot.20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Mayer JP, Zhang F, DiMarchi RD. J Pept Sci. 2007;88:687–713. doi: 10.1002/bip.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Belgi A, Hossain MA, Tregear GW, Wade JD. Immun Endoc & Metab Agents in Med Chem. 2011;11:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Akaji K, Fujino K, Tatsumi T, Kiso Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11384–11392. [Google Scholar]; b) Liu F, Luo EY, Flora DB, Mayer JP. Org Lett. 2013;15:960–963. doi: 10.1021/ol400149j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoelson SE, Lu ZX, Parlautan L, Lynch CS, Weiss MA. Biochemistry. 1992;31:1757–1767. doi: 10.1021/bi00121a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Sohma Y, Hua QX, Whittaker J, Weiss MA, Kent SBH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:5489–5493. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Avital-Shmilovici M, Mandal K, Gates ZP, Phillips NB, Weiss MA, Kent SBH. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3173–3185. doi: 10.1021/ja311408y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyfried MS, Lauber BS, Luedtke NW. Org Lett. 2010;12:104–106. doi: 10.1021/ol902519g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Murphy RC, Clay KL. Methods Enzymol. 1990;193:338–348. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)93425-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ponnusamy E, Jones CR, Fiat D. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1987;24:773–778. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnolzer M, Alewood P, Jones A, Alewood D, Kent SBH. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2007;13:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villain M, Vizzavona J, Rose K. Chem Biol. 2001;8:673–679. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Tam JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:2363–2370. [Google Scholar]

- 22.B. Dhayalan, K. Mandal, A. Tokmakoff, S. B. H. Kent, manuscript in preparation

- 23.Kent SBH. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:338–351. doi: 10.1039/b700141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran SD, Zanni MT. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5:1984–1993. doi: 10.1021/jz500794d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.