INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, the philosophy of diabetes care has evolved significantly. This drift has occurred in response to, and in parallel with, changes in the environment of diabetes care. A rapid increase in the number of people living with diabetes, availability of modern diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, and articulation of the need for patient-centered care[1] have changed the practice of diabetology. Newer modes of communication, such as telephony and the internet, in conjunction with enhanced variety and penetration of mass media, have revolutionized this field as well. These advances haves facilitated our move from the earlier, unipolar physician-centric model, to a bidirectional patient-physician construct, and now to the multipolar 3×3P rubric.[2]

THE SOCIAL DOMAIN

An understanding of the multifaceted 3×3P rubric allows one to assess and compare the various stakeholders which influence diabetes care. The family and community, of the person with diabetes, figure prominently among these.[3] Making up the social environment, they share a complex relationship with the diabetes epidemic.

Social environment (and support) determines health care-seeking and health care-accepting behavior of the person with diabetes. The social ecosystem influences attitudes toward medical pluralism, for example, choosing complementary and alternative therapy, along with, or over, evidence-based modern treatment. Availability, accessibility, and affordability of healthy eating options and opportunities for physical activity/exercise also influences the outcomes of diabetes management. On the other hand, diabetes creates challenges which may impact social relationships with caregivers and close ones, and with the community at large. These challenges span various aspects of life ranging from schooling and employment to recreation and marriage, as well as driving and insurance.[4]

SOCIAL COMPETENCE

The existence of these multitentacled relationships suggests that the astute diabetes care provider must be “socially competent.” Social sensitivity implies the ability to understand the dynamic and interactive relationship of diabetes with social life, and to express this during patient-provider dialog. Social competence implies the capacity of the diabetes care provider to appreciate these complexities and to respond to them with interventions (both nonpharmacological and drug-based), which are socially attractive, appropriate, acceptable, and of course, “accurate” or effective.

Unfortunately, social competence is not emphasized in medical curriculum as much as it should be. This leads to a situation where the health-care provider experiences a sociocultural disconnect with the patient she is treating. The near complete absence of training or exposure to qualitative research where a patient's perceptions can be systematically studied compounds this problem. Far too many educators believe that empathy can only be facilitated, but not taught. Such attitude precludes serious debate about curricular reforms. We need to actively strive toward creating more empathetic doctors.[5]

Over time, most doctors develop an intuition of what works and what does not work within a given geographic/ethnic framework. However, a significant amount of time is lost in the process, and the resulting heterogeneity of social competence is huge. Since senior physicians do not necessarily (or find it challenging to) transfer skills, knowledge, or attitudes beyond what are prescribed in the curriculum, the junior doctor starts the same process once he/she reaches the community. Like the character Naranath Bhranthan[6] in Kerala folklore, we keep repeating the same futile exercise in an infinite loop. The precious knowledge that needs to be preserved and propagated gets lost which needs to be addressed.

Social action

One of the easiest ways of improving the condition is to improve the communication skills of doctors. Even though the litigation culture is not common in our country, it is a well-known fact that doctors who communicate well and are liked by patients substantially reduce the risk of being sued.[7]

The trust deficit in hospitals is at its peak today, with both patients and doctors wary of each other.[8] This is reflected in the increasingly frequent attack on hospitals and doctors. Such a milieu results in patients' eventually seeking solace in dubious hope mongers. Diabetologists must realize that social competence is the kernel – the critical core upon which any successful medical practice can be built. While technological competence lets us reach more people more easily, it also has the potential to depersonalize medicine to some extent. This tendency can only be adequately combated by improving social competence of the treating physician.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL DOMAIN

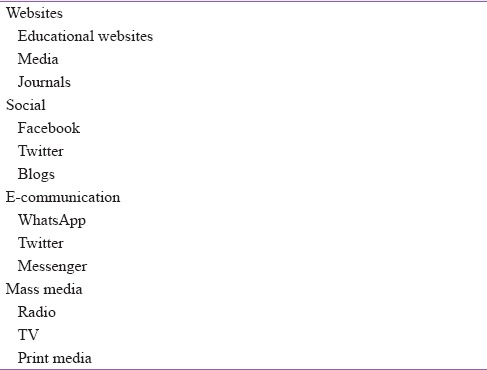

In today's world, availability of modern technology has revolutionized the way, in which persons seek, process, and utilize healthcare-related information.[9] While this access to knowledge does have advantages, it may come with a downside. The current status of various forms of communication [Table 1], including the worldwide web, messenger services, and online social media, does not allow for peer-review of publications. This means that a post with false, and potentially harmful, healthcare-related information, can be published as easily as a correct one. This exposes the person living with diabetes, and his or her caregivers, to potential ill-health. This situation creates a major challenge for the socially sensitive diabetes care professional.

Table 1.

Technosocial channels of communication

TECHNOSOCIAL COMPETENCE

The concept of diabetes therapy by the ear, published earlier, suggests the need for patient listening, and empathic counseling, in diabetes management.[10] This bidirectional process is actually a triptych of actions: Active listening, appropriate counseling, and artful filtering of accurate information from potentially damaging background noise (as received from hearsay and social media).

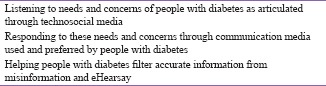

Diabetes therapy by the ear is traditionally practiced in a one-to-one or face-to-face encounter by the socially competent professional. With the flourishing of social media, however, diabetes care professionals will have to begin a proactive campaign for therapy by the ear on various technological platforms as well. This will involve three parallel missions: Listening to concerns of people with diabetes, facilitating resolution of these concerns, and helping them analyze various sources of information for accuracy and appropriateness [Box 1].

Box 1.

Diabetes therapy by the technosocial ear

Technological action

To do this, a certain degree of technological skills are required. These include familiarity with modern technology, understanding of its strengths, weakness, loopholes and limitations, and ability to utilize these to provide optimal diabetes care-related information. These skills are what we term as technological competence. Technical knowledge, in isolation, however, is not enough to spearhead a “diabetinformation” wave. Such knowledge must be interlinked with social sensitivity and social competence.

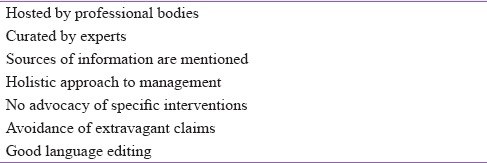

Technosocially competent professionals, therefore, are required to address the challenges of diabetes care, posed by evolving modes of information-hunting and communication. Apart from utilizing technosocial modes of communication, the techno socially savvy health-care provider should be able to equip persons in his care with the ability to differentiate de-information from de-misinformation. Some features of a reliable website are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Feature of reliable e-information

SUMMARY

Both social and technological competence is important attributes for the modern diabetologist. Just as we use the umbrella term “bio psychosocial” to explain health models, we should be able to utilize “techno social” to describe domains of competence that the diabetologist must develop, in addition to biomedical knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baruah MP, Kalra B, Kalra S. Patient centred approach in endocrinology: From introspection to action. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:679–81. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.100629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalra S, Baruah MP, Kalra B. Diabetes Care: Evolution of Philosophy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:495–7. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_109_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalra S, John M, Baruah MP. The Indian family fights diabetes: Results from the second diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs (DAWN2) study. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2014;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalra S, Sridhar GR, Balhara YP, Sahay RK, Bantwal G, Baruah MP, et al. National recommendations: Psychosocial management of diabetes in India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:376–95. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.111608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díez-Goñi N, Rodríguez-Díez MC. Why teaching empathy is important for the medical degree. Rev Clin Esp. 2017:pii: S0014-256530033-4. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhranthan N. Wikipedia. 2017. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 09]. Available from: https://www.en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Naranath_Bhranthan&oldid=772784757 .

- 7.To Be Sued Less, Doctors Should Consider Talking to Patients More-The New York Times. [Last cited on 2017 Apr 09]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/02/upshot/to-be-sued-less-doctors-should-talk-to-patients-more.html?_r=0 .

- 8.Kalra S, Unnikrishnan AG, Baruah MP. Interaction, information, involvement (The 3I strategy): Rebuilding trust in the medical profession. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:268–70. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_6_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salber P, Niksch A. Digital health tools for diabetes. J Ambul Care Manage. 2015;38:196–9. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalra S, Unnikrishnan AG, Baruah MP. Diabetes therapy by the ear. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:596. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.123541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]