Abstract

Purpose

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Lack of insurance coverage has been associated with more advanced disease at presentation, more emergent admissions at time of colectomy, and lower survival relative to privately insured patients. The 2006 Massachusetts health care reform serves as a unique natural experiment to assess the impact of insurance expansion on colorectal cancer care.

Methods

We used the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases to identify patients with colorectal cancer with government-subsidized or self-pay (GSSP) or private insurance admitted to a hospital between 2001 and 2011 in Massachusetts (n = 17,499) and three control states (n = 144,253). Difference-in-differences models assessed the impact of the 2006 Massachusetts coverage expansion on resection of colorectal cancer, controlling for confounding factors and secular trends.

Results

Before the 2006 Massachusetts reform, government-subsidized or self-pay patients had significantly lower rates of resection for colorectal cancer compared with privately insured patients in both Massachusetts and the control states. The Massachusetts insurance expansion was associated with a 44% increased rate of resection (rate ratio = 1.44; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.68; P < .001), a 6.21 percentage point decreased probability of emergent admission (95% CI, −11.88 to −0.54; P = .032), and an 8.13 percentage point increased probability of an elective admission (95% CI, 1.34 to 14.91; P = .019) compared with the control states.

Conclusion

The 2006 Massachusetts health care reform, a model for the Affordable Care Act, was associated with increased rates of resection and decreased probability of emergent resection for colorectal cancer. Our findings suggest that insurance expansion may help improve access to care for patients with colorectal cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Although earlier diagnosis and newer therapies have increased overall survival, disparities in access to and outcomes of care for colorectal cancer persist.1 Lack of insurance and other socioeconomic factors have been associated with lower rates of screening for colorectal cancer.2-5 Such social determinants are also associated with more advanced-stage cancer at time of diagnosis, greater likelihood of undergoing emergent resection, and lower survival relative to privately insured patients.6-9

Despite extensive evidence of disparities by insurance status, considerable debate remains regarding the drivers of and solutions to these differences. Colorectal cancer outcomes have been shown to vary by hospital, socioeconomic status of patients, and individual patient preferences or comorbidities.10-14 Disentangling the effect of these factors related to access and use of care for colorectal cancer has been challenging, given the considerable overlap among patient ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and insurance status.

The 2006 Massachusetts health reform provides a unique natural experiment to evaluate the impact of insurance expansion on access to and receipt of colorectal cancer treatment. The Massachusetts law, a model for the Affordable Care Act (ACA), expanded Medicaid coverage for those living below 150% of the federal poverty limit, created a state-subsidized insurance program (Commonwealth Care) for individuals whose income is less than 300% of the federal poverty limit but who remained ineligible for Medicaid, and established an individual mandate that required Massachusetts residents to carry health insurance. As a result, the uninsured rate fell to below 5%, with the majority of newly insured residents enrolled in either Medicaid or Commonwealth Care (Appendix Fig A1; online only).15-18 However, little is known about how this insurance expansion affected disparities in colorectal cancer.19

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate overall trends in colorectal cancer treatment after the 2006 Massachusetts health care reform. We hypothesized that the 2006 insurance expansion was associated with increased rates of colorectal cancer resection in the population most directly affected by the reform. A secondary hypothesis was that corresponding disparities by insurance status also decreased after the 2006 health care reform.

METHODS

Study Design and Data

We performed a cohort study using the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases (SIDs) in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Florida from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2011. The SIDs capture administrative data from approximately 98% of all discharges in respective states each year. Data are collected and maintained in partnership with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Our control states were selected on the basis of completeness and congruence of available covariates in the control states and Massachusetts as well as on the basis of a similar availability of surgical services, with comparable rates of colectomy within the respective states’ Medicare populations at the time of the Massachusetts law.20

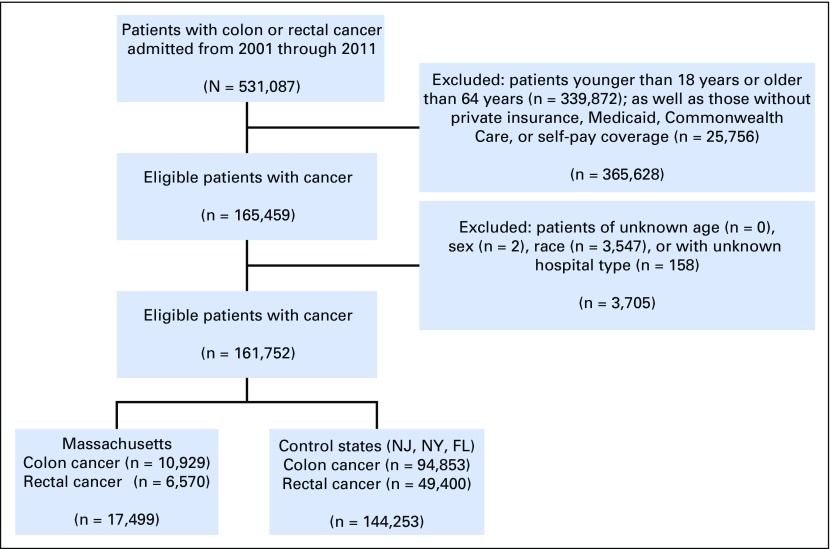

The study included all inpatient admissions of adult patients between the ages of 18 and 65 years with colorectal cancer who were uninsured or self-pay, or were covered by employee- or individually purchased private insurance coverage, Medicaid, or Commonwealth Care (only in Massachusetts after reform; Fig 1). Colorectal cancer diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes (ICD-9-Clinical Modification [CM] 153, 154, 153.0 to 154.8). Insurance coverage was classified as being government subsidized or self-pay (GSSP) if the primary payer was Medicaid, self-pay, no charge, or Commonwealth Care. This cohort represents the primary group of individuals who were affected by insurance expansion in Massachusetts or who would have been affected with similar reforms in the control states.21 Patients with Medicare and those younger than 18 years or older than 64 years were excluded from analyses because they were not affected directly by the Massachusetts reform.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of study design. Commonwealth Care insurance only available in Massachusetts after 2006 reform.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this study was surgical resection of colorectal cancer. Resection was defined using ICD-9 procedure codes (ICD-9-CM 173.1 to 173.9, 457.1 to 458.3, and 485.0 to 486.9). Secondary outcomes included the probability of emergent or elective admissions as defined using available variables in the SID.

Statistical Analysis

Difference-in-differences analyses were conducted to evaluate for changes in outcomes associated with the 2006 Massachusetts health reform.22-24 Indicator variables were created for intervention group (Massachusetts v control states), insurance status (GSSP v private insurance), and postreform. Prereform was defined as any discharge between the first quarter of 2001 and the second quarter of 2006. The postreform period was defined as any discharge between the first quarter of 2008 and the fourth quarter of 2011. Patients discharged between the second quarter of 2006 and the first quarter of 2008 were excluded because this was a period spanning the passage of the law and its full implementation. Previous studies showed that a significant portion of newly insured individuals gained insurance after enactment of the individual mandate in 2008.25

To evaluate for changes in treatment by insurance status, patients were stratified between GSSP and private insurance coverage. Difference-in-differences models included an interaction term between Massachusetts and the postreform period. The subsequent coefficient (the difference-in-differences estimator) represents the change in the outcomes associated with the 2006 intervention for GSSP patients.

We used Poisson regression models to evaluate resections as count data in this cohort study. Incident rate ratios (IRRs) were determined using the total population of adults 18 to 64 years of age with given insurance coverage in the respective cohorts. These population estimates were gathered using available resources from the US Census Bureau.26 The coefficient of these difference-in-differences Poisson models can be interpreted as the relative change in resection rates associated with the Massachusetts coverage expansion.

Ordinary least-squares regression models were used to evaluate for change in the probability of emergent or elective admission at the time of colorectal resection. The output of these difference-in-differences models represents the percentage point change in the probability of emergent or elective admissions independently associated with coverage expansion. Logistic regression models were used to determine disparities in the odds of resection before and after expansion in Massachusetts and the control states.

Risk Adjustment

Multivariable models examining changes in resection rates and rates of emergent admissions at the time of colon or rectal resection controlled for patient age, sex, ethnicity, and comorbidities using the Elixhauser comorbidity index.27 We also adjusted for hospital type and secular trends. Hospital types were defined using available SIDs variables and included investor-owned hospitals with all bed sizes, not-for-profit rural hospitals with all bed sizes, not-for-profit urban hospitals with < 300 beds, and not-for-profit urban hospitals with ≥ 300 beds. Standard errors were clustered at the hospital level using STATA’s cluster-correlated robust estimate of variance option (STATA, College Station, TX).28 Secular trends were defined on a quarterly basis using a continuous variable starting at the first quarter of 2001 and ending with the fourth quarter of 2011. In evaluating disparities in the odds of resection during admission, we also adjusted for metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis (ICD-9 196.0 to198.7, 198.82, 198.89).

Sensitivity Analyses

To confirm parallel trends in measures before reform, we conducted a separate analysis including only admission before reform. Sensitivity analyses were performed using a model with a triple interaction variable between Massachusetts, GSSP coverage, and postreform, which included the entire sample. We also evaluated identical models including admissions between the second quarter of 2006 and the first quarter of 2008. Additional sensitivity analyses were performed that stratified the patients by the presence of isolated liver metastasis, all other metastasis, or nonmetastatic disease.

The study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review. Data were analyzed using STATA software, version 14 (STATA, College Station, TX). Results were considered significant if P < .05.

RESULTS

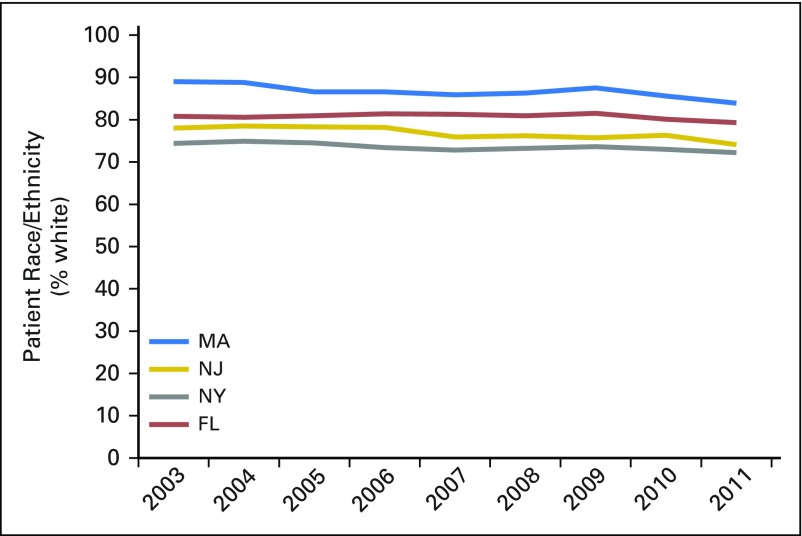

Our primary cohort consisted of 161,752 admissions, 17,499 from Massachusetts and 144,253 from the control states (Table 1). Patients in Massachusetts were more likely to be white, to have private insurance coverage, and to be admitted to a not-for-profit, urban hospital with < 300 beds. Massachusetts had a slightly higher percentage of patients with rectal cancer and a lower likelihood of presentation with metastatic disease. Patients in Massachusetts were also less likely to have an emergent admission at the time of colorectal resection. Patient age, sex, and comorbidity indices were comparable between Massachusetts and the control states.

Table 1.

Demographic and Oncologic Characteristics of Cohort

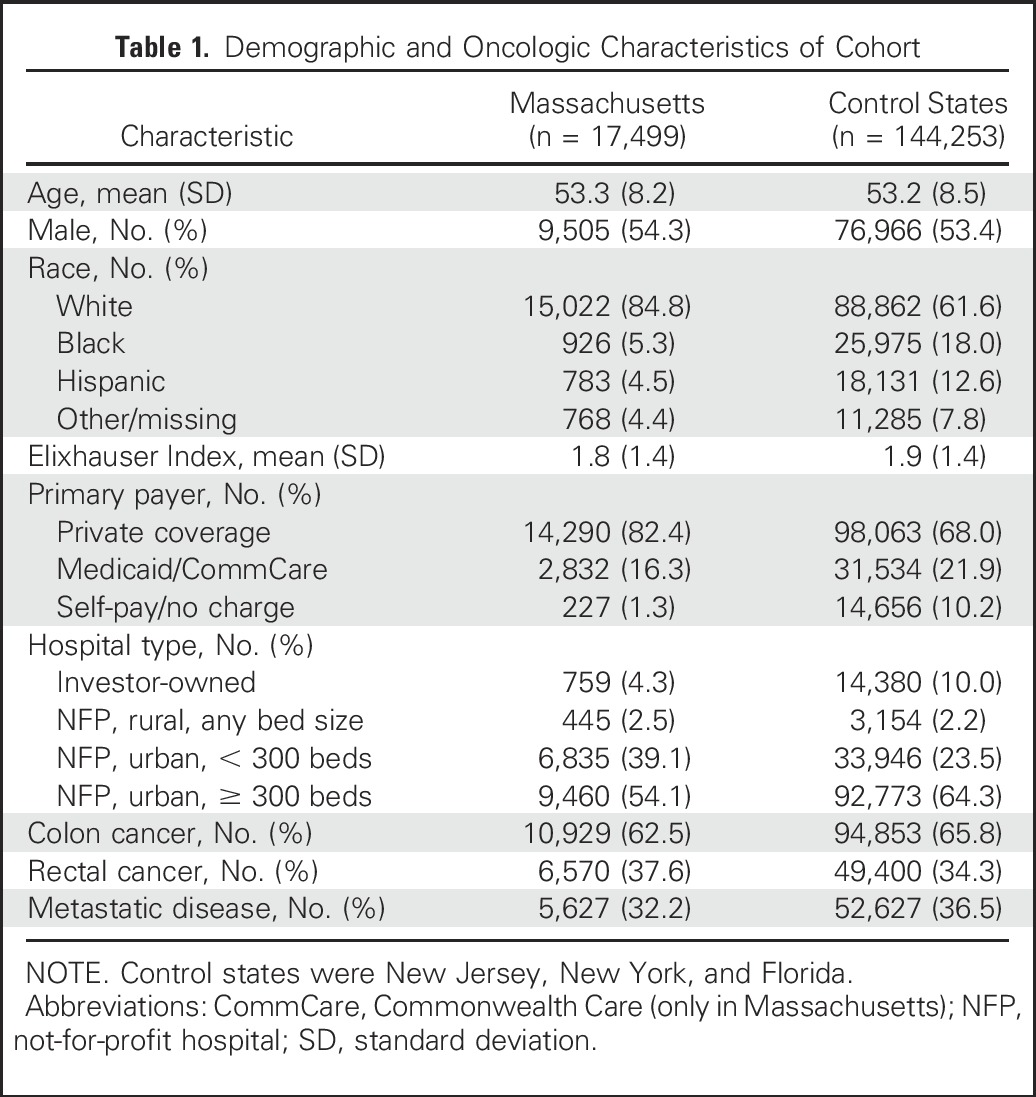

In examining trends in admissions for colorectal cancer, we found the Massachusetts reform to be associated with a 15% increased rate of admission of GSSP patients for colorectal cancer (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.16; P < .001), compared with the control states (Table 2). The coverage expansion was also independently associated with a 44% increased rate of resection (IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.68; P < .001) for GSSP patients admitted with colorectal cancer, compared with the control states. Stratifying by either colon or rectal cancer, the 2006 coverage expansion was associated with a 49% increased rate of resection for colon cancer (IRR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.26 to 1.77; P < .001) and a 34% increase rate of resection for rectal cancer (IRR, 1.34; 95% CI1.05 to 1.71; P = .021) for GSSP patients in Massachusetts, compared with the control states.

Table 2.

Impact of the Massachusetts Health Reform on Rates of Admissions and Surgery for Colorectal Cancer in GSSP Patients

Sensitivity analyses found that there was no differential trend in resection rates between GSSP patients in Massachusetts and the control states before coverage expansion (IRR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.02; P = .286). There was also no significant change in resection rates for privately insured patients in Massachusetts after the 2006 reform, compared with the control states (IRR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93 to 1.03; P = .455). The results of analyses using a triple interaction term with the complete sample were consistent with these findings. When stratifying by metastatic disease, we again found no significant change in resection rates for privately insured patients in Massachusetts with or without metastatic disease. However, the Massachusetts reform was associated with a 37% increased resection rate for GSSP patients in Massachusetts without metastatic disease at admission (IRR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.58; P < .001) and a 96% increased rate of resection for patients with isolated liver metastasis (IRR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.42 to 2.71; P < .001). There was no change in resection rates for GSSP patients with metastatic disease not in the liver.

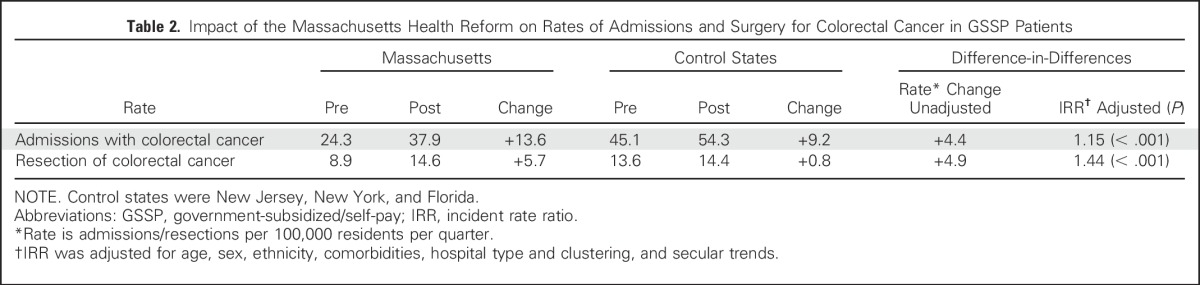

The Massachusetts coverage expansion was associated with a 6.21–percentage point decreased probability (95% CI, −11.88 to −0.54; P = .032) of an emergent admission at the time of resection and an 8.13–percentage point increased probability (95% CI, 1.34 to 14.91; P = .019) of an elective admission at the time of resection (Table 3). Before coverage expansion, there was no differential trend in emergent admissions or elective admissions for GSSP patients undergoing colorectal resection in Massachusetts, compared with the control states. There were also no significant changes in either emergent admissions or elective admissions for privately insured patients in Massachusetts after reform, relative to the control states. Sensitivity analyses including all GSSP and privately insured patients in a triple-interaction model demonstrated that GSSP patients still had significantly reduced probability of emergent admission and significantly increased probability of elective admission.

Table 3.

Impact of the Massachusetts Health Reform on Admission Type for GSSP Patients Undergoing Colorectal Resection

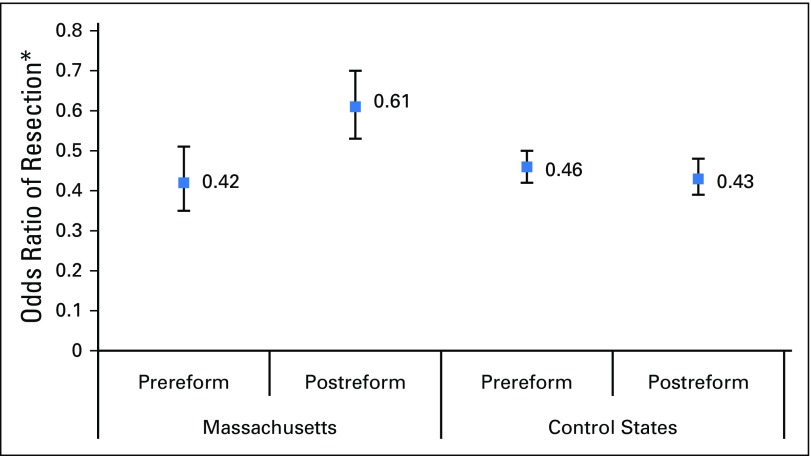

Before reform, GSSP patients had significantly lower odds of undergoing resection for colorectal cancer compared with privately insured patients in both Massachusetts (odds ratio [OR], 0.42; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.49; P < .001) and the control states (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.47; P < .001), controlling for patient age, sex, ethnicity, comorbidities, hospital type, and secular trends (Fig 2). After reform, these disparities decreased but remained significant in Massachusetts (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.72; P < .001). Disparities by primary payer remained unchanged in the control states after 2006 (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.47; P < .001).

Fig 2.

Impact of having government-subsidized/self-pay (GSSP) insurance on odds of undergoing resection among admitted patients with colorectal cancer. Control states were New Jersey, New York, and Florida. Reference group was the privately insured. *Odds ratio of resection at time of admission, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, comorbidities, and presence of metastatic disease, hospital type and clustering, and secular trends.

DISCUSSION

Lack of insurance coverage has long been linked to disparities in health and health care, including for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Disparities in coverage were a major driving force for the 2006 Massachusetts health reform, as well as for the ACA. Our results suggest that the Massachusetts coverage expansion was independently associated with a 44% increased rate of resection of colorectal cancer in the populations affected most directly by the law. The insurance expansion was also associated with an increase in the probability of resection being performed after an elective admission and a decreased probability of resection occurring after emergent admission. However, a gap in resection rates and emergent admissions at the time of surgery persists by payer status.

Although our results are not causal, a link between the coverage expansion and changes in the treatment received has several potential explanations. The increased rates of surgery could be caused by increased diagnosis of colorectal cancer at earlier stages, when resection is a more viable option. Previous studies in Massachusetts suggested that the 2006 health reform was associated with slight increases in rates of colonoscopy.29,30 Newly insured patients may also be more willing to present to the hospital with earlier signs or symptoms of cancer, with a decreased likelihood of presentation with obstructing, bleeding, or perforated tumors. In turn, these admissions may be for earlier, more surgically treatable tumors. Previous studies proposed such a hypothesis in explaining similarly increased resection rates for pancreatic cancer after the Massachusetts reform.31 Our results are consistent with previous work showing the Massachusetts reform to be associated with earlier presentation of other surgical diagnoses and increased probability of receiving optimal surgical intervention.32-34

Dissecting disparities in care by insurance status is more challenging, but our findings of increased odds of resection for GSSP patients after admission is encouraging, especially given the concurrent increased admission rate for GSSP patients in Massachusetts. Furthermore, disparities by payer status remained unchanged in the control states. These findings in Massachusetts, coupled with decreased emergent admissions at the time of surgery, suggest that patients are indeed undergoing resection more frequently and in the elective setting.

The disparity in the probability of resection by payer status was not eliminated completely in Massachusetts and could be caused by a variety of factors. First, we grouped all patients without insurance, with Medicaid, or with newly created Commonwealth Care into a single cohort, primarily to allow for comparison with a similar cohort in the control states. Unfortunately, we were unable to specifically identify those patients who obtained insurance after the Massachusetts reform. Therefore, a considerable number of patients in the Massachusetts cohort had Medicaid coverage both before and after expansion. Inclusion of these patients persistently insured through Medicaid in Massachusetts would have diluted any measured impact on the newly insured. Those with Medicaid before expanded eligibility tended to be less healthy and of higher risk from a sociodemographic standpoint than did those enrolling after expansion.35 These risk factors in those covered by Medicaid before reform should not necessarily have been expected to change after reform and could have contributed to the persistently lower odds of resection compared with privately insured patients. The study also did not address the independent influence of the individual mandate, which was a part of both the 2006 Massachusetts law and the ACA, on colorectal cancer care delivery.

We acknowledge several important limitations in this study. First, our data came from administrative records that do have the potential for coding errors. However, our analyses and results are consistent with previous studies of colorectal cancer using Hospital Cost and Utilization Project databases.36-38 Our analyses of admission and resection rates used population estimates from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics that may not capture the precise population. However, it is unlikely that errors in estimates would differentially occur within the GSSP cohort in Massachusetts as compared with other populations after 2006.

The study is also limited by a lack of clinical granularity, oncologic variables, and long-term survival data. Therefore, we cannot adequately account for stage at time of diagnosis or receipt of stage-appropriate treatment. We found no change in the rate of resection for patients with diffuse and extrahepatic metastases. Yet the increased rate of resection for patients with isolated liver metastasis suggests that expansion may influence delivery of care for patients with more advanced but potentially curable cancer.39 In the absence of more clinically granular data, however, we cannot definitively exclude the possibility of inappropriate resection of advanced-stage disease. The SIDs capture only inpatient admissions and therefore, we were unable to identify patients diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer in the outpatient setting, although if they presented to the hospital for surgery, then those admissions would have been captured. Additional studies using population-level data for all new patients diagnosed with colon cancer might provide more granular data on overall diagnosis and stage-specific treatment. However, surgery remains the primary means of curative treatment and occurs almost exclusively within an inpatient setting. Our results suggest that insurance expansion was associated with increased rates of resection.

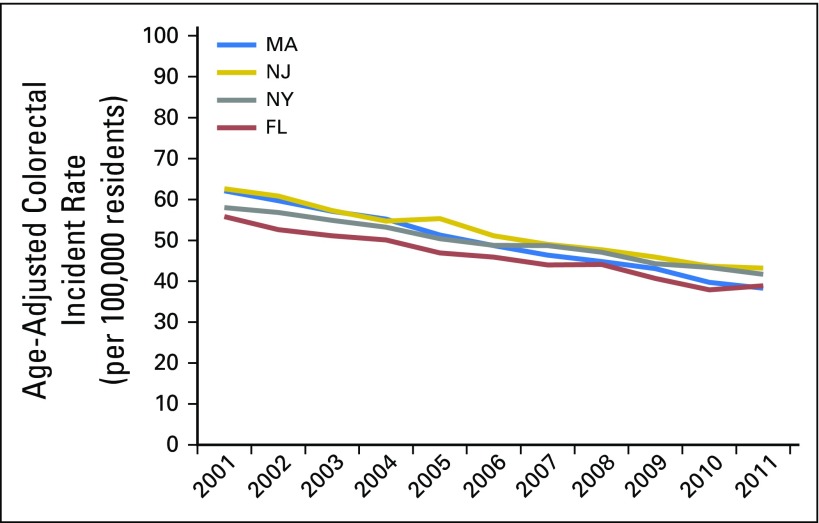

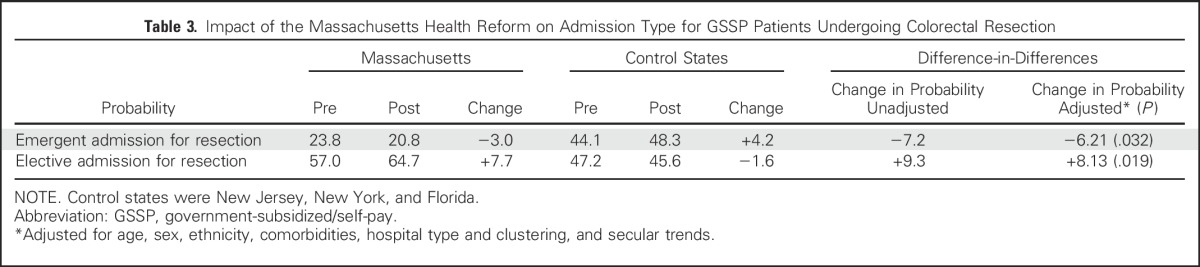

As a quasi-experimental study, we also acknowledge the possibility of other ecologic changes that could have differentially affected the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. However, there was no differential trend in incidence rates of colorectal cancer between Massachusetts and the control states over the study period (Appendix Fig A2, online only).40 Similarly, there were no differential changes in race/ethnicity (Appendix Fig A3, online only).15 To our knowledge, there were no other broad, population-level policy changes that occurred in Massachusetts that could account for our findings. Given the unique aspects of health care in the state, our findings in Massachusetts may not be generalizable elsewhere. However, our evaluation of resection rates and admission types before the reform showed similar trends in both Massachusetts and the control states before implementation. Furthermore, our inclusion of privately insured patients as a separate, intrastate control group still demonstrated significantly increased rates of surgery and a decreased probability of emergent resection for GSSP patients in Massachusetts after coverage expansion. Regardless, additional study of access to and receipt of optimal care for colorectal cancer in other states that expand coverage through the ACA will provide important insights into the impact elsewhere in the country.

In this study, we show that the 2006 Massachusetts insurance expansion was associated with a 44% increased rate of resection for colorectal cancer and a 6.21 percentage point decreased probability of an emergent admission at the time of colorectal resection. Despite these improvements in care, disparities by payer persist for colorectal resection rates and odds of emergent admission at the time of resection. Longer-term evaluations in Massachusetts and other states are needed to evaluate the impact of ACA-related coverage expansions on the treatment of colorectal cancer. Overall, the Massachusetts experience provides cautiously optimistic evidence that expanded insurance coverage may help facilitate more equitable access to and receipt of cancer care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the National Bureau of Economic Research (Cambridge, MA) through which data were made available. In addition, databases are maintained through the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project’s data partners, including the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, the New Jersey Department of Health, and the New York State Department of Health.

Appendix

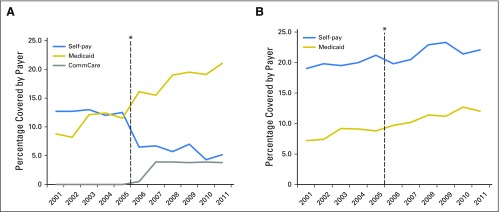

Fig A1.

Trends in government-subsidized and self-pay insurance coverage in (A) Massachusetts and (B) control states. *2006 Massachusetts health reform law. CommCare, Commonwealth Care.

Fig A2.

Trends in age-adjusted incidence rates of colon and rectum cancer, by state. Data adapted.40

Fig A3.

Trends in race/ethnicity, by state. Data adapted.

Footnotes

Supported in part through a predoctoral MD/PhD National Research Service Award from the National Institute on Aging (Award No. 1 F30 AG 039175).

Presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium, Boston, MA, March 3, 2016.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andrew P. Loehrer, Matthew M. Hutter, John T. Mullen

Provision of study materials or patients: Zirui Song

Collection and assembly of data: Andrew P. Loehrer, Zirui Song

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Impact of Health Insurance Expansion on the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Andrew P. Loehrer

No relationship to disclose

Zirui Song

No relationship to disclose

Alex B. Haynes

No relationship to disclose

David C. Chang

No relationship to disclose

Matthew M. Hutter

No relationship to disclose

John T. Mullen

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010;116:544–573. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, et al. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ioannou GN, Chapko MK, Dominitz JA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening participation in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2082–2091. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004;100:2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, et al. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpern MT, Pavluck AL, Ko CY, et al. Factors associated with colon cancer stage at diagnosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2680–2693. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0669-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: Findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer. 2008;113:582–591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins AS, Pavluck AL, Fedewa SA, et al. Insurance status, comorbidity level, and survival among colorectal cancer patients age 18 to 64 years in the National Cancer Data Base from 2003 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3627–3633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Iyer A, et al. Association of area sociodemographic characteristics and capacity for treatment with disparities in colorectal cancer care and mortality. Cancer. 2011;117:4267–4276. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breslin TM, Morris AM, Gu N, et al. Hospital factors and racial disparities in mortality after surgery for breast and colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3945–3950. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhoads KF, Ackerson LK, Jha AK, et al. Quality of colon cancer outcomes in hospitals with a high percentage of Medicaid patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee W, Nelson R, Mailey B, et al. Socioeconomic factors impact colon cancer outcomes in diverse patient populations. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:692–704. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landrum MB, Keating NL, Lamont EB, et al: Reasons for underuse of recommended therapies for colorectal and lung cancer in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer 118:3345-3355, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Naishadham D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Siegel R, et al. State disparities in colorectal cancer mortality patterns in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1296–1302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Census Bureau: Current Population Survey (CPS). http://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html

- 16. Massachusetts household survey on health insurance status, 2007. Boston, MA, Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy, 2007. http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/58018/ocn690284055.pdf?sequence=1.

- 17. Health Insurance Coverage in Massachusetts: Results from the 2008-2010 Massachusetts Health Insurance Surveys. Boston, MA, Division of Health Care Finance and Policy, 2010. http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/70747/ocn707396421.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 18. Long SK, Stockley K: Health reform in Massachusetts: An update as of fall 2009. http://bluecrossmafoundation.org/∼/media/Files/Publications/Policy%20Publications/060810MHRS2009FINAL.pdf.

- 19.Zhu J, Brawarsky P, Lipsitz S, et al. Massachusetts health reform and disparities in coverage, access and health status. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:1356–1362. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Lebanon, NH, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. www.dartmouthatlas.org/ [PubMed]

- 21. Division of Health Care Finance and Policy: Access to health care in Massachusetts: Results from the 2008-2010 Massachusetts Health Insurance Surveys for non-elderly adults (ages 19 through 64). http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/109940/ocn725895012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 22.Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donald SG, Lang K. Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat. 2007;89:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Athey S, Imbens GW. Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-differences models. Econometrica. 2006;74:431–497. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. The importance of the individual mandate–Evidence from Massachusetts. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:293–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1013067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Census Bureau Historic tables. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/HIB_tables.html.

- 27.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rogers WH: Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1993;13:19-23. Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints, vol. 3, 88-94.

- 29.Van Der Wees PJ, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Improvements in health status after Massachusetts health care reform. Milbank Q. 2013;91:663–689. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okoro CA, Dhingra SS, Coates RJ, et al. Effects of Massachusetts health reform on the use of clinical preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2865-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.09.010. Loehrer AP, Chang DC, Hutter MM, et al: Health insurance expansion and treatment of pancreatic cancer: Does increased access lead to improved care? J Am Coll Surg 221:1015-1022, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, et al. Massachusetts health care reform and reduced racial disparities in minimally invasive surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, et al. Influence of health insurance expansion on disparities in the treatment of acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 2015;262:139–145. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loehrer AP, Hawkins AT, Auchincloss HG, et al. Impact of expanded insurance coverage on racial disparities in vascular disease: Insights from Massachusetts. Ann Surg. 2016;263:705–711. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill SC, Abdus S, Hudson JL, et al. Adults in the income range for the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion are healthier than pre-ACA enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:691–699. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson CN, Chen GJ, Balentine CJ, et al. Minimally invasive surgery is underutilized for colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1412–1418. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alnasser M, Schneider EB, Gearhart SL, et al. National disparities in laparoscopic colorectal procedures for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang CY, Halabi WJ, Chaudhry OO, et al. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:65–71. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: United States Cancer Statistics (USCS): 1999–2013 Cancer incidence and mortality data. http://www.cdc.gov/uscs.