Comparison of olfactory and taste receptor mRNA protein expression and chemotactic migration assays suggests chemosensory-type subsets in circulating leukocytes.

Keywords: chemosensory GPCR, olfactory, saccharin, lactisole, siRNA, blood leukocytes

Abstract

Our cellular immune system has to cope constantly with foodborne substances that enter the bloodstream postprandially. Here, they may activate leukocytes via specific but yet mostly unknown receptors. Ectopic RNA expression out of gene families of chemosensory receptors, i.e., the ∼400 ORs, ∼25 TAS2R bitter-taste receptors, and the TAS1R umami- and sweet-taste receptor dimers by which we typically detect foodborne substances, has been reported in a variety of peripheral tissues unrelated to olfaction or taste. In the present study, we have now discovered, by gene-specific RT-PCR experiments, the mRNA expression of most of the Class I ORs (TAS1R) and TAS2R in 5 different types of blood leukocytes. Surprisingly, we did not detect Class II OR mRNA. By RT-qPCR, we show the mRNA expression of human chemosensory receptors and their cow orthologs in PMN, thus suggesting an evolutionary concept. By immunocytochemistry, we demonstrate that some olfactory and taste receptors are expressed, on average, in 40–60% of PMN and T or B cells and largely coexpress in the same subpopulation of PMN. The mRNA expression and the size of subpopulations expressing certain chemosensory receptors varied largely among individual blood samples, suggesting a regulated expression of olfactory and taste receptors in these cells. Moreover, we show mRNA expression of their downstream signaling molecules and demonstrate that PTX abolishes saccharin- or 2-PEA-induced PMN chemotactic migration, indicating a role for Gi-type proteins. In summary, our data suggest "chemosensory"-type subpopulations of circulating leukocytes.

Introduction

Blood leukocytes express a large variety of 7-transmembrane helix GPCRs [1, 2], for instance, chemokine receptors [3, 4], free fatty acid receptors [5, 6], bradykinin receptors [7], prostanoid receptors [8], complement receptors [9], or formyl-peptide receptors [10], to detect bacterial infections or to orchestrate an immune response. Moreover, our cellular immune system not only is exposed continuously to endogenous cytokines, hormones, growth factors, and mediators but also to exogenous foodborne chemicals, such as aroma compounds or tastants, which may enter the bloodstream postprandially [11–13]. Thus, it is widely accepted that our cellular immune system responds to certain food ingredients or metabolites [5, 14–18]. However, their molecular targets on our immune cells remained largely unknown so far. Recently, we have demonstrated in different types of isolated human blood leukocytes the functional expression of members of an olfactory receptor family, the TAARs [19–21], which detect certain biogenic amines with high sensitivity [22, 23]. In this study, we have set out to explore in different types of blood leukocytes the expression of other chemosensory receptors, such as ORs [24–26], bitter-taste receptors (TAS2Rs) [27–30], and sweet- and umami-taste receptors (TAS1Rs) [31, 32]. These chemosensory receptors are typically expressed within the sensory cells of the olfactory epithelium in the nose or the taste buds of the tongue and have evolved to decode nature’s signatures of smell and taste, enabling the hedonic detection and differentiation of food, and to prevent ingestion of poisonous substances [33, 34]. However, there is growing yet mostly RNA-based evidence of an ectopic expression of chemosensory receptors in a variety of peripheral tissues [35–46]. Gene expression of few chemosensory receptors in leukocytes in general or in erythroid cells has been reported in few studies by means of RT-PCR [47], microarray RNA hybridization [48], or RNA sequencing [38], but data on identified OR, TAS1R, and TAS2R gene expression in these cells were sparse and not consistent.

Here, we investigate the mRNA expression of OR and taste receptors in isolated human PMN, B cells, T cells, NK cells, and monocytes by means of RT-PCR experiments and compare the mRNA expression levels of these chemosensory receptors in isolated human and cow PMN and of their signaling molecules in human PMN by RT-qPCR experiments. For some receptor proteins, we show their coexpression in PMN and T and B cells by means of immunocytochemistry, co-IP, and WB experiments, as well as a food aroma compound-induced function by means of PMN chemotaxis and transmigration assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies

The following chemicals were used: 2-ME, N-lauroylsacorsine sodium salt, and sodium citrate (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany); Ficoll and RPMI 1640, containing L-glutamine (Biologic Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel); PBS (J.T.Baker, Munich, Germany); CsCl (Molekula, Shaftesbury, United Kingdom); EDTA, Tris/HCl, SDS, methanol, acetone, HCl, and chloroform (BDH & Prolabo, Leuven, Belgium); GITC (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany); butanol (Riedel-de Haën, Seelze, Germany); PFA (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA); CellTak (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA); and pertussis toxin (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom). 2-PEA, lactisole, and fMLF (also known as fMLP) were provided by Sigma-Aldrich.

Reagents for PCR include: DNAse-I (Baseline Zero, Biozym, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany); iScript cDNA synthesis kit and SsoFast Eva Green Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA); GoTaq Green (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) and GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA); and VisiBlue dye (TATAA Biocenter, Gothenburg, Sweden). Gene-specific oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Eurofins-MWG (Ebersberg, Germany) and Biomers (Ulm, Germany; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Antibodies include: rabbit anti-human OR51B6, rabbit anti-human OR56B4 biotin-labeled, and rabbit anti-human OR52A4-Atto 488-labeled antibodies (Assay Biotechnology, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and rabbit anti-human TAAR1 (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-human TAS1R1-Atto 488-labeled, rabbit anti-human TAS1R2 biotin-labeled, and rabbit anti-human TAS1R3 antibodies were provided by Biozol (Eching, Germany). Rabbit anti-human TAS2R38 antibody was provided by Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom) and rabbit anti-human TAS2R43/31 by Antibodies-online (Aachen, Germany). Secondary antibodies goat anti-rabbit MFP488 and goat anti-rabbit MFP555 were purchased from Mobitec (Goettingen, Germany). Blood leukocyte-positive selection was performed by use of anti-CD14+, -CD3+, -CD19+, and -CD56+ magnetobead-conjugated antibodies from Miltenyi Biotec (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Chemicals for immunocytochemistry include Hoechst-33342, TSA Alexa Fluor 488 and streptavidin Alexa Fluor 633 kits, provided by Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA).

co-IP and IB include Dynabeads Protein G immunoprecipitation kit (Life Technologies, Oslo, Norway) and goat anti-rabbit HRP secondary antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

siRNA transfection: TAS1R1, TAS1R2, and TAS1R3-siRNA were obtained from Eurofins-MWG. Gα-gustducin-siRNA was provided by Qiagen by use of FlexiTube GeneSolution (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Non-siRNA was AllStars Negative Control (Qiagen). For siRNA, we used PeqFECT transfection reagent (PeqLab, Erlangen, Germany).

Human and bovine blood cell purification

Human blood leukocytes were isolated from buffy coat samples (n = 47; Bavarian Red Cross Blood Bank, Munich, Germany). Bovine PMN were isolated from peripheral blood, obtained from 6 healthy female Brown Suisse cows (Research Station Veitshof, Physiology Weihenstephan, Freising, Germany). Human and bovine blood leukocytes were purified by use of Ficoll density gradient centrifugation, as described previously [22]. Blood leukocyte-positive selection was performed by use of anti-CD14+ (monocytes), -CD3+ (T cells), -CD19+ (B cells), and -CD56+ (NK cells) magnetobead-conjugated antibodies from Miltenyi Biotec [22]. The purity of isolated leukocytes was confirmed by flow cytometry (MACSQuant analyzer; Miltenyi Biotec) and was always >90%. The cells were resuspended further at 1 × 106/ml concentration in RPMI 1640 or in GITC buffer [22] for RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA from blood leukocytes was isolated and purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation, as described previously [22]. Moreover, to avoid genomic DNA contamination, the RNA preparation was followed by a DNAse-I (Baseline-Zero; Biozym, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany) digestion. The quality of RNA was tested in 12 randomly selected humans and in all 6 bovine RNA samples by Experion automated electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) by use of standard sense RNA analysis LabChips, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplemental Fig. 1). The quality of tested RNA samples was determined by the RNA quality index, which ranged between 7.8 and 9.7. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by use of the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

RT-PCR

The presence of RNA transcripts for human Class I and Class II OR was investigated initially by RT-PCR in all 5 cell types by use of sets of 8- to 512-fold degenerate oligonucleotide primers (Biomers; Supplemental Materials and Methods and Supplemental Table 1), constructed to detect highly conserved regions within Class I or Class II OR at the beginning of TMII or the end of TMIII. PCR reactions were performed with the use of GoTaq PCR Master Mix (1/2 reaction volume; Promega, Mannheim, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

The presence and individual distribution of 55 Class I OR, 27 Class II OR, 25 TAS2R, and 3 TAS1R in different blood cells were evaluated further by RT-PCR by use of cDNA, as described previously (ref. [22] and in Supplemental Materials and Methods). Sequences for all gene-specific primers (Eurofins MWG) are listed in Supplemental Materials and Methods. The ability of primers to enable receptor-specific amplicons was tested by PCR by use of genomic or plasmid DNA (Supplemental Figs. 2–4).

The identity of human and bovine Class I OR, TAS2R, and TAS1R was confirmed by Sanger sequencing of ∼50% (randomly selected) of all agarose gel-purified amplicons. RT-PCR data were evaluated as percentage of positive Class I OR-, TAS2R-, or TAS1R-specific amplicons/cell type and across all blood samples, as observed in agarose gel electrophoresis.

RT-qPCR

RNA expression level of human and bovine orthologs for Class I OR, TAS2R, and TAS1R in PMN was quantitatively compared with RT-qPCR (n = 15, and n = 6, respectively) as relative expression, normalized to an average of 6 selected and stably expressed reference genes (GAPDH, RNA polymerase II A, β2-microglobulin, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1, ribosomal protein L13a, and actin-like protein), according to the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments Guidelines [49]. The selection of the references genes was done by geNorm and NormFinder software [50]; further normalization was performed among human or among bovine receptors, each to their respective reference, gene-controlled, lowest RNA expression level, which was set as 1. All RT-qPCR reactions on human PMN cDNA were performed by use of GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in an Mx3000P cycler (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA): 95°C (3 min), 40× [95°C (15 sec), 58°C (30 sec), 72°C (30 sec)]. Cq data were evaluated by use of MxPro software (Stratagene), and Cq values ≥38 were considered negative.

mRNA expression in cow PMN for human orthologs was performed in a CFX384 cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany). RT-qPCR was performed by use of the SsoFast EvaGreen Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) by the following master mix and cycle protocol: 5 μl SsoFast EvaGreen Kit (2×), 0.4 μl forward primer (10 μmol/L), 0.4 μl reverse primer (10 μmol/L), 0.07 μl VisiBlue dye (TATAA Biocenter), and 3.13 μl RNase-free water, which were added with 1 μl cDNA to a final 10 μl for qRT-PCR analysis. qPCR amplification was performed in white, 384-well plates (4titude, Wotton, Surrey, United Kingdom). The following qPCR cycling protocol was used for all investigated genes: denaturation for 5 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of a 2-segmented amplification, and quantification program: 95°C (15 sec), followed by annealing and elongation (60 sec) at a primer-specific annealing temperature (Supplemental Table 2). A melting analysis was performed by slow heating from 65°C to 95°C with a dwell time of 5 sec, increment 0.5°C, and continuous fluorescence measurement. Cq and melting curves were acquired by use of CFX384 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany).

Immunocytochemistry

Isolated blood leukocytes were fixed with 4% PFA and permeabilized with methanol/acetone (1:1). Protein expression in human blood PMN and T and B cells of selected Class I OR, TAS2R, and TAS1R was evaluated by immunocytochemistry by use of receptor-specific primary antibodies and 5% blocking solution (TSA kit; Invitrogen), each overnight at 4°C.

Class I OR

Rabbit anti-human OR51B6-specific primary antibody (1:200; Assay Biotechnology) was applied for 24 h at 4°C, following 2 h application of the secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP555 (1:200; Mobitec). Rabbit anti-human OR56B4 biotin-labeled (1:200) and rabbit anti-human OR52A4 Atto 488-labeled (1:200) primary antibodies (Assay Biotechnology) were then applied for 24 h at 4°C. Signals of OR56B4 biotin-labeled antibody were amplified with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1000; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature.

TAS1R

Rabbit anti-human TAS1R3-specific primary antibody (1:250) was applied for 24 h at 4°C, following 2 h application of the secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP555 (1:200; Mobitec). Rabbit anti-human TAS1R2 biotin-labeled (1:200) and rabbit anti-human TAS1R1 Atto 488-labeled (1:500) primary antibodies were then applied for 24 h at 4°C. All TAS1R were provided by Biozol. Signals of TAS1R2 biotin-labeled antibody were amplified with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1000; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunocytochemistry for confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Olympus IX81; Olympus, Melville, NY, USA) for TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 was performed by use of the same experimental conditions, except for secondary antibody for TAS1R3; here, the goat anti-rabbit MFP-488 (1:250) was used.

TAS2R

Rabbit anti-human TAS2R38 primary antibody (1:3500; Abcam) was applied for 24 h at 4°C, following the secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP555 (1:200; Mobitec) for 2 h. Rabbit anti-human TAS2R43/31 primary antibody (1:500; Antibodies-online) was applied for 24 h at 4°C. The secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP555 (1:200; Mobitec) was applied for 2 h. Specificity of the TAS2R43/31 antibody was tested in transiently transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells (see Supplemental Fig. 9).

TAAR1

Immunocytochemistry for TAAR1 was performed as described previously [22].

Specificity and efficiency of immunocytochemistry were confirmed by randomly testing selected antibody staining (TAS1R2-Alexa Fluor 633) by flow cytometry by use of PFA-fixated cells in a MACSQuant (Miltenyi Biotec).

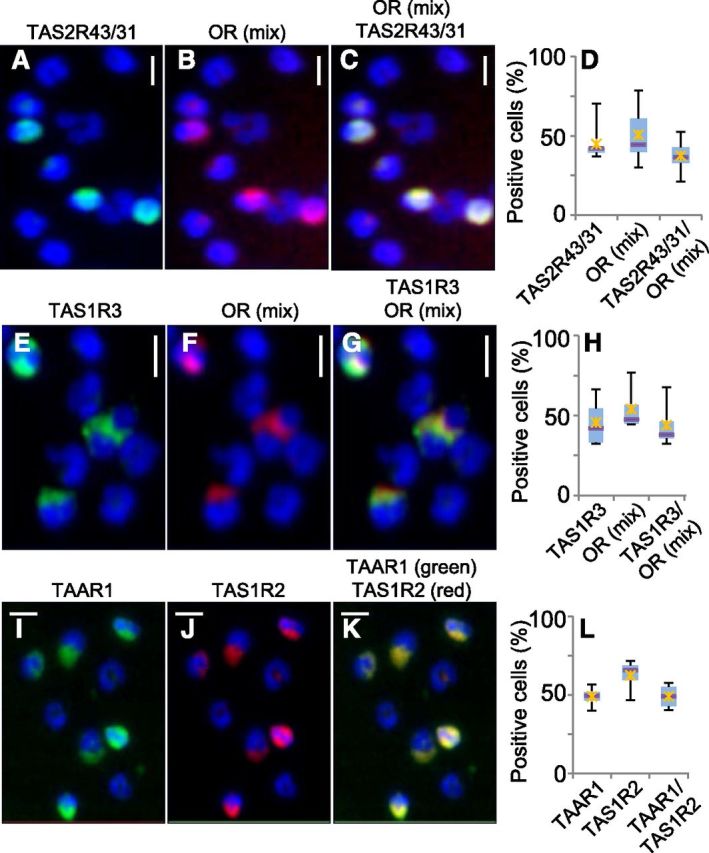

Coexpression of Class I OR, TAS2R, TAS1R, and TAAR1

TAS2R43 coexpression with selected Class I OR was investigated as follows: TAS2R43-specific primary antibody (1:500) was applied for 24 h at 4°C, following the application of secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP488 (1:250) for 2 h. A primary antibody mixture (ratio 1:1:1) of OR56B4, OR51B6, and OR52A4 biotin labeled (1:200) was then applied for 24 h at 4°C. OR-biotin and all biotin-labeled signals described further were always amplified with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 633 (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature.

For the detection of a TAS1R3, coexpression with selected Class I OR rabbit anti-TAS1R3 antibody (1:250) was applied on the cells for 24 h at 4°C, following the secondary antibody application (goat anti-rabbit MFP488, 1:250; Mobitec) for 2 h. Finally, a mix (ratio 1:1:1) of biotin-labeled OR56B4, OR51B6, and OR52A4 (1:200) was applied for 24 h at 4°C.

For the detection of a coexpression of TAS1R2 with TAAR1, rabbit anti-human TAAR1 (1:200; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) was applied for 24 h at 4°C. The secondary antibody goat anti-rabbit MFP488 (1:250; Mobitec) was then applied for a further 2 h. Finally, biotin-labeled rabbit anti-TAS1R2 (1:200) was added for the next 24 h at 4°C. Investigation of a TAS2R38/TAS2R43 coexpression was hardly possible, as both antibodies were raised in the same species, preventing the use of different secondary antibodies, and moreover, were provided diluted in serum, preventing their direct labeling.

WB, co-IP, and IB

WB was performed for TAS1R2 by use of a pool of 10 independent human PMN samples. The cell preparation was the same as described previously [22]. After an ultracentrifugation step, the pellets were resuspended in 200 µl protease buffer by passing them through a 23-G needle. Ultrafiltration (Vivaspin 500; Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) was performed further to concentrate the protein >3 kDa. Samples were eluted further in elution buffer (1:1 total vol 40 µl). The eluted protein was separated by 4–20% gradient PAGE, and further steps were as described previously [22]. We used the same primary anti-TAS1R2 antibody as for immunocytochemistry (1:1000, 4°C, overnight). Secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit HRP; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was added for 1 h (1:5000), and all further steps were performed, as described previously [22].

co-IP and IB for TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 were performed as described previously [22]. Five micrograms/sample of anti-TAS1R3 antibody was covalently linked to Dynabeads Protein G (Life Technologies, Oslo, Norway) for Co-IP. Antibody concentrations were the same as described above for WB.

Chemotaxis and transmigration assays

PMN chemotaxis toward saccharin (100 µM) was performed by use of the 2D CellDirector chemotaxis assay (Gradientech, Uppsala, Sweden), which enables the analysis of cell migration and cell behavior within chemotactic concentration gradients. PMN were seeded in the chemotaxis chamber, and live cell imaging of individual cell tracking was monitored under light microscope at 0.033 Hz for 1 h. Migration data from both gradient conditions, as well as from controls, were collected. PMN tracking was analyzed offline by use of the Tracking Tool software (Gradientech). Mean accumulated and Euclidean distance (micrometers), migration velocity (micrometers/min), and the percentage of migrated PMN were analyzed. The significance of chemotactic migration was confirmed by use of Rayleigh test (P < 0.05). PMN migration within RPMI-1640 medium was used as a negative control.

PMN transmigration assays were performed in 48-well microchambers (Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Some PMN samples were pretreated with PTX (3 µg/ml) for 15 min at 37°C before chemotaxis assay. Tested substances (2-PEA, saccharin in the presence/absence of lactisole, or lactisole alone) were diluted in RPMI 1640 and applied to the lower wells of the microchamber, and the assay was processed as described previously [22]. Cell migration toward test substances was determined by counting migrated cells/well by use of a Neubauer chamber (Marienfeld, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany) under an Axiovert 40C light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), and the results were normalized to the number of migrated cells in the presence of fMLF (5 nmol/L) as 100%, which served as a positive control. Data were fitted to the function (f) = {(a − d)/[1 + (×/EC50)h] + d}, where a = minimum, d = maximum, and h = Hill coefficient.

siRNA knockdown

Protein expression of TAS1R1, TAS1R2, TAS1R3, or signal transduction component Gα-gustducin in PMN was silenced by 44 h siRNA transfection (n = 4–8). Gene-specific siRNA was designed according to Reynolds et al. [51]. Target sequences were as follows: CAGGTCTTGTAGCTTCAATGA (TAS1R1), CAGCGTGTACTCTGCGGTCTA (TAS1R2), CAGGGCTAAATCACCACCAGA (TAS1R3), and TTGAAGGAGTTACATGCATTA (Gα-gustducin). In brief, transfection mix, containing 10–30 nM siRNA or non-siRNA and transfection reagent, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, was applied on purified blood PMN suspensions. All transfections were performed at 37°C, 5% CO2, humidified atmosphere. PMN transmigration assays toward lactisole were performed 44 h post-transfection.

Data analysis and statistics

RT-PCR data are presented as a heat map, color intensity coded by percentages of receptor-positive RT-PCR over the total RT-PCR number for the respective receptor (percent of receptor-positive blood samples). qRT-PCR data are presented as a relative target RNA expression compared with mRNA expression of 6 selected, stably expressed reference genes. Only genes with clear melting curves and single specific product peaks were taken for further data analysis. Samples that showed irregular melting peaks were excluded from the quantification procedure. Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the significant differences between the abundance of different chemosensory receptors in different cell types.

The nuclei of the cells for immunocytochemistry were stained with Hoechst-33342 (350/461 nm, excitation/emission; Invitrogen). Fluorescence signals were taken by a BD Pathway 855 bioimaging system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed offline by use of AttoVision and BD Image Data Explorer software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); OR51B6, TAS1R3, TAS2R43/31, and TAS2R38 signals were detected by MFP-555 (560/585 nm); OR56B4 and TAS1R2 by Alexa Fluor 633 (632/647 nm); and OR52A4 and TAS1R1 by Atto 488 (501/523 nm). At least 2000 cells for PMN and 30,000 for T and B cells were analyzed. Data are presented as Box-whisker plots, spanning minimum and maximum values.

Confocal laser-scanning microscope data were analyzed with FV1200/FV1000 Viewer software Version 4.1 (Olympus).

RESULTS

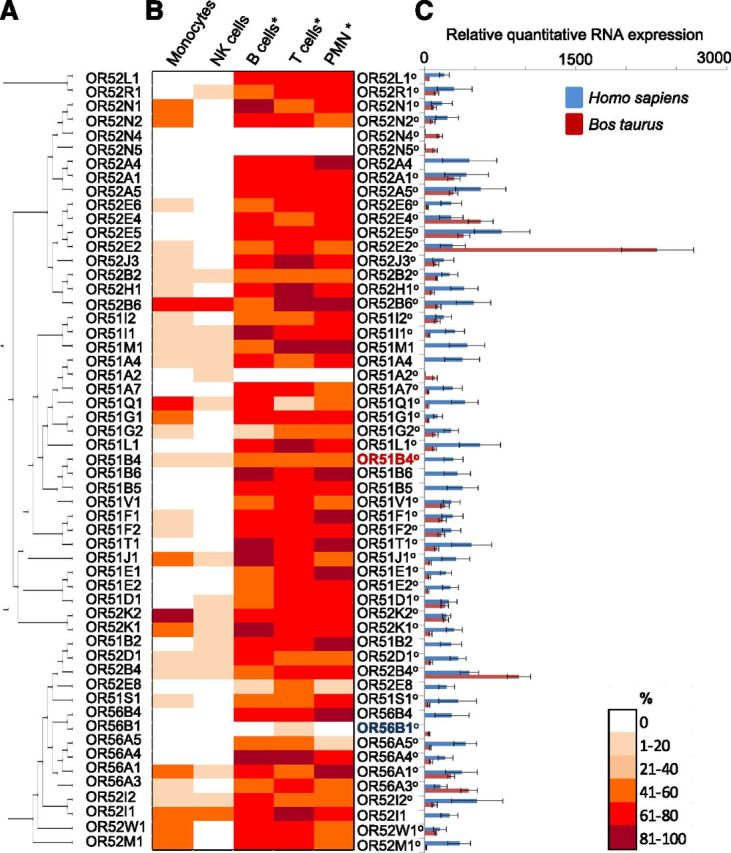

Class I OR but not Class II OR gene transcripts are expressed in human and bovine blood leukocytes

The reported ectopic RNA expression of few OR in leukocytes or erythroid cells [38, 47, 48], as well as our own previous identification of members of an olfactory receptor family (TAAR) being functionally expressed in several types of leukocytes [22], motivated us to investigate the expression of OR in monocytes; NK, T, and B cells; and PMN, which we isolated from fresh, human buffy-coat samples. Human OR separate into 2 major phylogenetic clades, commonly addressed as Class I and Class II OR [52, 53]. To identify gene transcripts of the 2 OR classes in leukocytes, we designed degenerate oligonucleotides, according to highly conserved regions at the intracellular borders of TMII and -III of Class I and Class II OR (Supplemental Table 1). As we got RT-PCR amplicons only for Class I OR but not for Class II OR in all 5 tested blood leukocyte types (Supplemental Figs. 1–4), we then used gene-specific primers for all 55 human Class I OR in RT-PCR experiments with RNA from monocytes; NK, T, and B cells; and PMN.

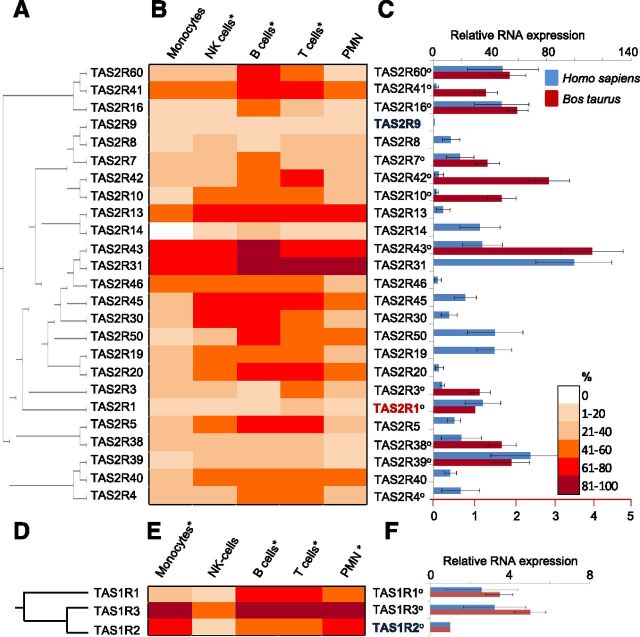

We confirmed the presence of 53 Class I OR (Fig. 1A) in several blood leukocyte types by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B), with the highest abundance for Class I OR transcripts correlating significantly with PMN and B and T cells. Transcripts for the most of Class I OR in these cells were detected in >60% of tested blood samples. Generally, Class I OR gene transcripts in monocytes and NK cells were detected rarely, with the lowest abundance of Class I OR transcripts in NK cell samples. We have never obtained RT-PCR amplicons for the phylogenetical highly related OR52N4 and OR52N5 in blood leukocytes. OR51A2 and OR56B1 RT-PCR amplicons were obtained selectively from NK or T cells, respectively, albeit with low abundance.

Figure 1. Class I OR gene transcripts are expressed in human and bovine blood leukocytes. (A) Phylogenetic tree of 55 human Class I OR was calculated by use of the progressive alignment algorithm from CLC Main Workbench (Version 6.8.2; CLCbio/Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark) software. The tree was created by use of CLC bio’s high-accuracy, neighbor-joining algorithm with 100 bootstrap replicates. (B) RT-PCR analysis with gene-specific primers revealed Class I OR RNA expression with different abundances in different types of blood leukocytes and over n = 10 different blood samples. *Cell types with significant, different abundances (ANOVA). (C) RT-qPCR demonstrates relative quantitative Class I OR mRNA expression in blood PMN for human receptors and their cow orthologs (o). Data were normalized to an averaged expression of 6 different reference genes, with the lowest value [human, OR56B1 (blue); cow, OR51B4 (red)] set as 1. Shown are means ± sem (n = 15).

We next asked how transcript levels are displayed across Class I OR. For RT-qPCR experiments, we selected PMN, according to the high abundance of RT-PCR amplicons for Class I OR in these cells. We observed a large variation of relative receptor-specific transcript levels (Fig. 1C). The lowest transcript levels were observed for OR56B1, which we never detected by RT-PCR. Compared with that, OR52E5 RNA expression was ∼700-fold higher (Fig. 1C). Notably, relative mRNA expression levels for most of Class I OR correlated directly to their RT-PCR amplicon-based abundance (Fig. 1B and C). We picked the cow to investigate OR gene expression in a species with modes of nutrition and digestion different than human but with a high genome homology to human [54] and a large number of OR genes [55]. We found that 84% of human Class I OR genes have putative, isofunctional, heterospecic homologs (orthologs) in the cow. We quantified transcript levels for 46 Class I OR putative orthologs from bovine PMN, sharing >80% sequence identity with their closest related human OR. Similar to human PMN, we observed a high variation of relative receptor-specific RNA quantity (Fig. 1C). We observed the lowest transcript levels for bovine OR51B4 and 2300-fold higher transcript levels for bovine OR52E2, whereas relative RNA expression for most of the bovine Class I OR was 200- to 300-fold higher compared with OR51B4 (Fig. 1). The averaged Cq values ranged from 27 to 31 over all bovine and human chemosensory receptor qPCR experiments.

In contrast to previous studies, suggesting the presence of several Class II OR in human blood leukocytes [38, 56], we were not able to detect RT-PCR amplicons for Class II OR in any of the 5 leukocyte types investigated (Supplemental Fig. 3) by use of degenerate oligonucleotide primers (Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, the use of gene-specific oligonucleotides for those 27 selected Class II OR, for which ectopic RNA expression had been reported previously [38, 56], in our hands, did not reveal any Class II OR-specific RT-PCR amplicons, at least in human PMN (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Gene transcripts for all TAS2R and TAS1R are expressed in human blood leukocytes

The presence of taste receptors in specific human blood cell types has never been reported. However, 1 study suggested the presence of several human TAS2R and TAS1R gene transcripts in RNA prepared from whole-blood leukocytes [38]. Here, we investigate the presence of gene transcripts for 25 human TAS2R and 3 TAS1R in 5 different blood leukocyte types. With the analysis of cDNA from 28 to 33 different blood donors, we obtained RT-PCR amplicons for all known human TAS2R and TAS1R (Fig. 2A, B and D, E) in all tested, specific leukocyte types, albeit with different abundance for specific leukocyte types. Generally and in contrast to Class I OR, the highest abundance for TAS2R transcripts correlated significantly with NK, B, and T cells. However, transcripts for TAS2R43 and TAS2R31 were the most abundant in all tested cell types, with transcripts for TAS2R31 showing an “OR-type” pattern of abundance, preferentially being present in >80% of tested PMN and T and B cell samples.

Figure 2. TAS2R and TAS1R gene transcripts are expressed in human blood leukocytes. (A and D) Phylogenetic trees of 25 human TAS2R and 3 TAS1R. (B and E) RT-PCR analysis with gene-specific primers revealed TAS2R and TAS1R mRNA expression with different abundances in different types of blood leukocytes and over n = 28–33 different blood samples. *Cell types with significant, different abundances (ANOVA). (C and F) RT-qPCR demonstrates relative quantitative TAS1R and TAS2R mRNA expression in blood PMN for human receptors (blue) and their cow orthologs (o; red). Data were normalized to an averaged expression of 6 different reference genes, with the lowest values set as 1 (human, TAS2R9 and TAS1R2; cow, TAS2R1 and TAS1R2). (C) Upper scale, Human receptors; lower scale, cow receptors. Shown are means ± sem (n = 15).

Our RT-qPCR based analysis of RNA expression among TAS2R in human blood PMN revealed the lowest and highest relative RNA expression for TAS2R9 and TAS2R31 (∼100-fold higher), respectively (Fig. 2C). TAS2R31 RNA was also most abundantly detected over all tested blood samples (Fig. 2B).

The cow has 16 functional TAS2R genes [57, 58], of which, we identified 12 as putative orthologs [58] to human genes. In PMN, we obtained RT-qPCR signals for 11 out of the 12 tested bovine TAS2R. In contrast to human TAS2R, the relative RNA expression among bovine TAS2R orthologs showed little variation, differing only up to 4-fold, with the lowest and highest relative RNA expression for bovine TAS2R1 and TAS2R43, respectively (Fig. 2C).

The presence of human TAS1R gene transcript was detected in 5 different human blood cell types (Fig. 2E), and similarly to TAS2R, it did not depend highly on cell type. However, TAS1R1 transcript was more often detected in the cells of adaptive immunity and T and B cells, whereas TAS1R2 was observed more frequently in those cells orchestrating an innate immune response, PMN, and monocytes. Transcripts for TAS1R3, a common part of the sweet- and umami-taste receptor heterodimers, were significantly more abundant than TAS1R1 or TAS1R2. We found TAS1R3 transcripts in >80% of all tested human blood samples in all cell types, except NK cells, where it was detected in ∼50% of samples. Notably, in 10–20% of tested leukocyte samples, we detected gene transcripts for only TAS1R3 but not for TAS1R1 and TAS1R2. The relative RNA expression of TAS1R was similar in PMN from the human and cow, differing up to 3-fold among the human TAS1Rs and up to 5-fold among the bovine TAS1Rs (Fig. 2F). The highest RNA expression was detected for TAS1R3 in PMN from both tested species.

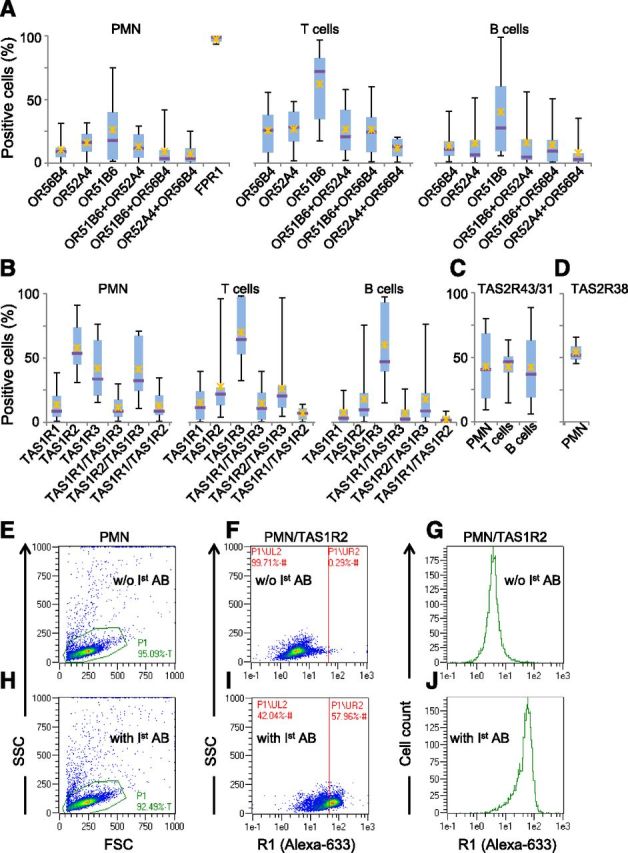

Immunocytochemistry reveals protein expression of Class I OR, TAS1R, and TAS2R in PMN and T and B cells

We then asked whether different, most abundant receptors from the same chemosensory modality coexpress in the same cells or not. In the olfactory system, typically only 1 OR allele is expressed per olfactory sensory neuron in the nose [59–61]. In contrast, different types of bitter-taste receptors may be coexpressed in the same Type II taste cell in the taste buds of the tongue [62]. Whereas flow cytometry would appear to be the method of choice to answer this question for blood cells, the lack of antibodies suitable for life cell staining prevented us from the use of this method. However, some antibodies were suitable for receptor-specific 2-color immunocytochemistry on PFA-fixed and acetone/methanol-permeabilized cells. Again, the quality of the antibodies available limited the number of investigated receptors in our study. We studied protein expression of receptors from all 3 Class I OR families—OR51B6, OR52A4, and OR56B4—which before, were among those receptors with the most abundant RNA expression over all cell types and blood samples tested (Fig. 1B). As OR52A4 has been suggested very recently to be a pseudogene as a result of a C-terminal frame shift [58], we amplified, subcloned, and sequenced the C-terminal coding regions and identified 5 different OR52A4 haplotypes from the 8 blood samples investigated (Supplemental Table 3). The haplotypes lacked an OR-typical C-terminal signature ("PMLNPF/LIY" [63]), however all had open reading frames compared with the reference sequence in HORDE [26, 64]. OR51B6 immunocytochemistry revealed, on average, 26%, 62%, and 40% positive cells in PMN and T and B cells, respectively (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 5). Immunocytochemistry signals for OR52A4 and OR56B4 were observed, on average, in 16% and 10% of PMN, in 25% and 27% of T cells, and in 16% and 14% of B cells, respectively (Fig. 3A). For the 3 OR investigated, we observed overlapping signals in the same cells; however, the signals never overlapped completely (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 5). The detection methods for the 3 OR were diverse, as the primary antibodies used were labeled directly or required detection by a labeled secondary antibody or labeled streptavidin. We thus decided to use the same detection method for all OR by labeling all 3 primary anti-OR antibodies together in a 1:1:1 stoichiometry with biotin and then visualizing antibody binding with streptavidin-coupled Alexa Fluor 633. By this approach, we repeatedly observed, on average, 52% stained PMN (Fig. 4B, D, F, and H), which is exactly the sum of the average percentage of stained PMN from the experiments by use of single, OR-specific antibodies (Fig. 3A; PMN). However, for each receptor investigated by immunocytochemistry, the Box-whisker plots showed a wide range of percentages of positively stained cells across the individual blood samples (Figs. 3 and 4). In sharp contrast, this was not the case for the bacterial FPR1, at least in PMN, which we detected by the same technique to be homogenously expressed in all cells (97 ± 2.5%) and across all tested blood samples (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 8).

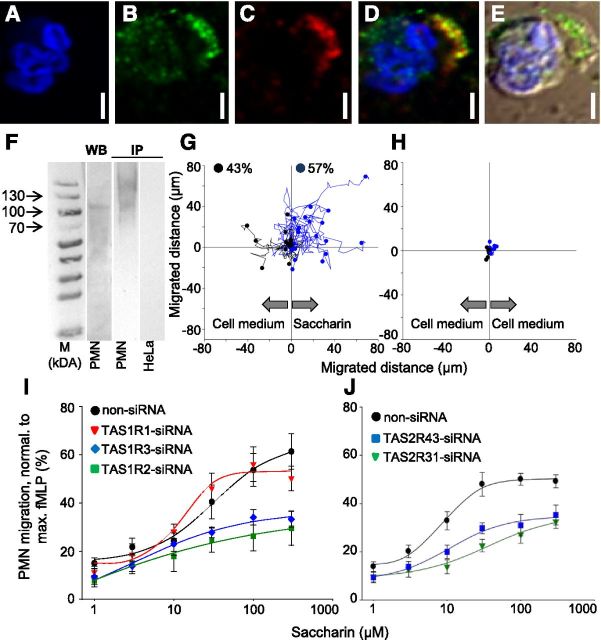

Figure 3. Chemosensory receptor protein expression in subpopulations of human blood leukocytes. Box-whisker plots display the percentage of immunocytochemistry-derived signals of Class I OR (A), TAS1R (B), TAS2R43/31 (C), and TAS2R38 (D) expression in PMN and T and B cells (see also Supplemental Figs. 6–8). Filled bars indicate 2nd and 3rd quartiles of data distribution, with error bars spanning 100% of data. Horizontal lines indicate median; X, data mean. In total, 2749–15,185 PMN, 36,058–76,720 T cells, and 39,496–64,115 B cells from n = 4–11 different blood samples were analyzed. Original magnification, 40×. (For FPR1, see also Supplemental Fig. 9). The efficiency and specificity of TAS1R2 biotin-labeled antibody were confirmed by flow cytometry in PMN under the same experimental conditions as in usual immunocytochemistry. TAS1R2 signals were amplified with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 633. PMN morphology after cell fixation, and full immunocytochemistry procedure was determined by forward-scatter (FSC; 270 nm) and side-scatter (SSC; 410 nm; E and H) criteria. The intensity of TAS1R2 signals was detected by side-scatter and R1 channel (635 nm; F–J). w/o 1st AB, without primary antibody.

Figure 4. Two-color immunocytochemistry reveals coexpression of Class I OR, TAS2R, TAS1R, and TAAR1 in human blood PMN. (A–C) Coexpression of Class I OR (1:1:1 mix of OR56B4, OR52A4, and OR51B6) and TAS2R43/31. PMN (2474), from n = 7 blood samples, were analyzed. (E–G) Coexpression of Class I OR (1:1:1 mix of OR56B4, OR52A4, and OR51B6) and TAS1R3. PMN (2301), from n = 4 blood samples, were analyzed. (I–K) Coexpression of TAAR1 and TAS1R2. PMN (2377), from n = 4 blood samples, were analyzed. Original scale bars, 5 μm. (D, H, and I) Box-whisker plots display the percentage of receptor-positive cells. Lower and upper blue bars indicate 2nd and 3rd quartiles of data distribution; horizontal lines, median; X, data mean.

Immunocytochemistry revealed TAS1R protein expression in PMN and T and B cells. We observed the lowest expression for the umami-taste receptor subunit TAS1R1 with, on average, 7–15% of stained cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the sweet-taste receptor subunit TAS1R2 or the sweet- and umami-taste receptor subunit TAS1R3 was detected, on average, in 58% or 42%, 28% or 70%, and 18% or 60% of PMN and T and B cells, respectively (Fig 3B and Supplemental Fig. 6). By taking PMN, which had been fixed and labeled by the same procedures and antibodies as in Fig. 3A–D, into flow cytometry (Fig. 3E–J), we detected the same percentage of TAS1R2-positive cells (58%; Fig. 3I and J) as in our immunocytochemistry experiments. In contrast, life cell staining revealed only ∼15% of TAS1R2-positive PMN in flow cytometry (data not shown).

We investigated the protein expression of TAS2R43/31 in human PMN, as in these cells, 1) they were expressed most abundantly (Fig 2B and C), and 2) just as the TAS1R2/TAS1R3 sweet-taste receptor, they are known to be activated by saccharin, a nonmetabolized artificial sweetener [65]. TAS2R38 has been known to mediate taste responses to a variety of thioamides, and TAS2R38 alleles have been associated with long-term trends in tobacco use and food preferences [66]. Immunocytochemistry revealed expression of bitter-taste receptor TAS2R43 and/or its homolog TAS2R31 (90% aa identity), on average, in 42% of PMN and T and B cells and of TAS2R38 in 54% of PMN (Fig. 3C and D and Supplemental Fig. 7). The fact that primary antibodies against TAS2R43/31 and TAS2R38 were raised in the same species and were supplied in serum-containing buffer prevented us from the use of different secondary antibodies or from labeling these antibodies directly and differentially. Therefore, we refrained from investigating coexpression of TAS2R.

Olfactory and taste receptors are largely coexpressed in a subpopulation of PMN

We then asked whether in PMN, olfactory and taste receptors coexpress in the same cells. Different combinations of 2-color immunocytochemistry experiments gave largely overlapping signals, revealing that Class I OR (by use of 1:1:1 stoichiometry of anti-OR51B6, -OR52A4, and -OR56B4 antibodies) coexpresses with the bitter-taste receptors TAS2R43/31 (Fig. 4A–C) and with the sweet- and umami-taste receptor subunit TAS1R3 (Fig. 4E–G), on average, in 37% and 44% of cells, respectively (Fig. 4D and H). Moreover, the TAAR1 coexpressed with the sweet-taste receptor subunit TAS1R2 (Fig. 4I–K), on average, in 49% of PMN (Fig. 4L).

Saccharin-induced PMN chemotaxis by activating the sweet-taste receptor TAS1R2/TAS1R3 and the bitter-taste receptors TAS2R31 and TAS2R43

In Type II taste cells, the TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 subunits dimerize to function as a sweet-taste receptor [32]. As we found that TAS1R2 largely coexpressed with TAS1R3 in the same leukocytes (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. 6), and both subunits had the highest abundance in PMN (Fig. 2E), we investigated their coexpression pattern at higher resolution by performing confocal laser-scanning, 2-color immunocytochemistry for the 2 sweet-taste receptor subunits in PFA-fixed PMN. We found that the signals for both subunits partially overlapped in vesicles lining up at the cell surface (Fig. 5A–E). Moreover, we got WB signals, as well as IB signals, for TAS1R2 after co-IP with a magnetobead-coupled antibody against TAS1R3 (Fig. 5F). We refrained from performing co-IP with TAS1R1, however, because of the low percentage of TAS1R1-positive cells observed across all blood samples (Fig. 3B).

Figure 5. TAS1R protein expression and functional relevance of saccharin receptors in human blood PMN. (A–F) Immunocytochemistry and confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed an expression and coexpression of TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 in blood PMN. (A) Blue color indicates nucleus staining; green (B) and red (C) signals represent TAS1R3 and TAS1R2 signals, respectively. (D) Merge of signals from B and C, with overlapping signals appearing in yellow. (E) Overlay of the transmission light picture of the same cell. (F) WB and immunoprecipitation (IP) show the presence of TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 in protein preparations from PMN but not from HeLa, which was used as a negative control. The predicted size of TAS1R2 protein is 95 kDa but may run higher as a result of glycosylation. ‘M, Size marker. (G) Chemotaxis of PMN toward saccharin in a gradient between RPMI and 100 μmole/L saccharin or (H) in RPMI 1640 (negative control) was performed in a 2D CellDirector Opal chamber (Gradientech). Shown are percentage and distance of 40 migrated PMN. Similar results were obtained from 3–6 independent experiments. Transmigration assay (I and J) shows a saccharin-induced TAS1R2-, TAS1R3-, TAS2R31-, and TAS2R43- but not TAS1R1-dependent PMN migration. PMN migration, Normalized to a maximum fMLF response (5 nmole/L; n = 8–12); non-siRNA represents a negative knockdown control; there, none of the receptors are silenced. Data are mean ± sd.

Furthermore, we asked whether we can induce a cellular function in PMN via their chemosensory receptors. In vivo, during the innate immune response, PMN leave blood vessels and actively migrate along a chemoattractant gradient toward a site of tissue injury or infection [67]. Therefore, we tested whether the food-borne aroma compound saccharin, which is a known agonist for the sweet-taste receptor in micromole/liter concentrations [68, 69], as well as for the bitter-taste receptors TAS2R31 and TAS2R43 [68–70], can activate chemotaxis in isolated human PMN. We found that 56.9 ± 5.2% of PMN performed chemotaxis in a gradient toward saccharin, with an accumulated and Euclidean distance of 56.7 ± 9.7 µm and 21.3 ± 2.3 µm compared with an accumulated and Euclidean distance of 2.8 ± 0.3 µm and 2.3 ± 0.4 µm in RPMI (Fig. 5G and H). Moreover, saccharin activated PMN migration in a concentration-dependent manner in chemotactic transmigration assays with an EC50 of 9.89 ± 1.59 µmol/L (Fig. 5I and J).

To test whether a chemotactic migration of PMN toward saccharin depended on TAS1R2 or TAS1R3 or both, we transfected isolated PMN with siRNA against 1 of the 3 TAS1R subunits or with siRNA against the bitter-taste receptors TAS2R43 or TAS2R31. We found that siRNA against the sweet-taste receptor subunits TAS1R2 or TAS1R3 knocked down PMN migration toward saccharin to a similar degree by ∼50% (Fig. 5I). Likewise, siRNA, against 1 of the 2 bitter-taste receptors cognate for saccharin, TAS2R43 or TAS2R31, abolished PMN migration toward saccharin by ∼50% (Fig. 5J). In contrast, we did not observe a loss of function in PMN transfected with siRNA against the umami-taste receptor subunit TAS1R1 or in non-siRNA-transfected PMN (Fig. 5I).

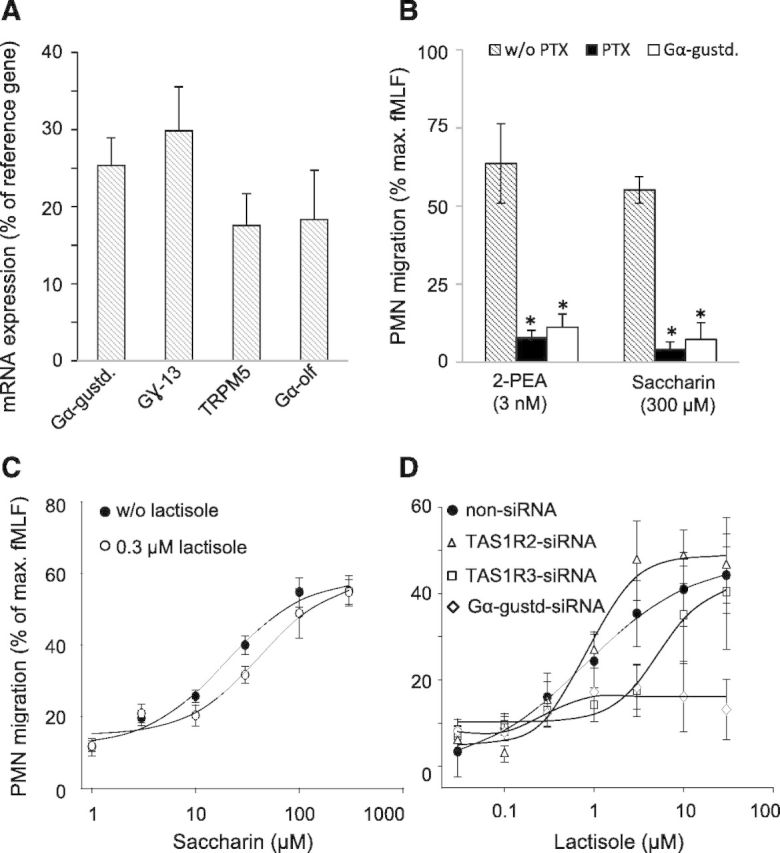

Do leukocytes express olfactory and taste signaling molecules? Flegel et al. [38] suggested the mRNA expression of several olfactory signaling molecules, such as Gα-olf, in a "whole leukocyte" preparation. Here, we show mRNA expression at levels of 17.6–29.9% of reference genes for Gα-gustducin, Gα-olf, Gγ-13, and TRPM5 in PMN. Their expression levels (Fig. 6A) were similar to the average mRNA expression of 15.8 ± 11.2% of reference genes of all identified human chemosensory receptors in PMN.

Figure 6. G Protein α-gustducin knockdown and lactisole effects on saccharin-induced and TAS1R-mediated PMN migration. (A) RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates relative mRNA expression of Gα-gustducin, Gɣ-13, TRPM5, and Gα-olf in human blood PMN. Data were normalized to an averaged expression of 2 different reference genes as 100%. Shown are means ± sem (n = 7–12). (B) 2-PEA (3 nmole/L) and saccharin (300 µmole/L) stimulated PMN chemotaxis, which was largely abolished by pretreating PMN with PTX (3 µg/ml) or by transfecting them with siRNA against α-gustducin. *P < 0.05 compared with without PTX condition. Data are mean ± sd. (C) Lactisole at 0.3 µmole/L is an antagonist on the saccharin-induced PMN migration. (D) Lactisole itself induces TAS1R3-dependent PMN migration. (B–D) The maximum number of migrated PMN, normalized to a maximum fMLF response (5 nmole/L; n = 4–14).

PTX binds to G protein α subunits of the Gi-type [71], thereby disrupting signaling from their cognate GPCR. PTX-sensitive G proteins of the Gi-type family are known to be involved in PMN chemotactic migration [72]. The taste-related G protein α-gustducin is a member of the Gi-type family of proteins. To test whether PTX-sensitive G proteins, in general, or α-gustducin, in particular, are involved in a chemoreceptor-induced signaling, leading to PMN migration, we investigated the migration behavior of PMN that had been pretreated with PTX or transfected with siRNA against α-gustducin before stimulation with the volatile biogenic amine 2-PEA or with saccharin. We used 2-PEA at a concentration of 3 nmol/L, which has been shown to elicit maximum TAAR1-dependent chemotactic migration in isolated human PMN [22]. We used saccharin at a concentration of 300 μmol/L, which has been shown to activate the sweet receptor (TAS1R2/TAS1R3) in submillimolar concentrations [69] and also has been shown to be an agonist for the bitter-taste receptors TAS2R43 and TAS2R31 [70]. We observed chemotactic migration of 63.7 ± 7.9% and 55.2 ± 4.1% of isolated PMN for 2-PEA and saccharin, respectively (Fig. 6B). This percentage of migrated PMN was reduced largely by pretreatment of PMN with PTX (Fig. 6B). Likewise, siRNA against gustducin largely abolished PMN migration toward 2-PEA or saccharin (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the sweet-taste blocker lactisole, which binds to the TAS1R3 subunit of the sweet-taste receptor heterodimer, inhibited a saccharin-induced PMN migration (EC50 = 19.49 ± 6.11 µmol/L; n = 6), albeit only at a rather low concentration of 0.3 µmol/L (EC50 = 41.21 ± 19.66 µmol/L; n = 6; Fig. 6C). Interestingly, we found that lactisole itself triggered PMN migration in a concentration-dependent manner, with an EC50 of 0.79 ± 0.14 µmol/L; Fig. 6D), which was largely attenuated in PMN with siRNA knockdown of TAS1R3 (EC50 = 5.40 ± 0.18 µmol/L) or siRNA knockdown of α-gustducin (Fig. 6D). TAS1R2 knockdown (EC50 = 0.86 ± 0.22 µmol/L) or transfection with non-siRNA had no impact on lactisole-induced PMN migration (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

The concept of expression of olfactory and taste receptors in different primary human blood leukocyte types is new. So far, there have been only 3 reports on mRNA expression of few chemosensory receptors and only in total leukocyte RNA preparations [38, 47, 48]. Recently, we demonstrated a subpopulation of, on average, ∼60% PMN that functionally coexpressed the biogenic amine receptors TAAR1 and TAAR2 [22]. TAAR, too, may be considered olfactory receptors, at least from experiments with rodents [19, 20, 73].

In the present study, we demonstrate specific expression of the ancient Class I OR repertoire but not Class II OR in blood leukocytes, which corroborates the notion of rather water-soluble ligands for Class I OR, at least according to the literature [34]. However, we cannot exclude an expression of Class II OR, as our methods may not have been sensitive enough. Of the putative orthologs in the cow, the majority (but also 92% of TAS2R orthologs) came up as RT-qPCR signals. At least 78% of Class I OR orthologs in the cow display RNA expression levels in PMN that are comparable with human PMN, despite different modes of nutrition and digestion between the 2 species, suggesting evolutionary conserved functions of chemosensory receptors in blood neutrophils. Blood, however, is an ancient tissue, and beyond an expression of ancient Class I OR genes, the expression of early B cell factor (OLF1; O/E-1) in differentiating B lymphocytes and olfactory receptor neurons is yet another common feature of the blood cellular immune system and, at least, the olfactory epithelium [74, 75]. Thus, whether a tissue expression of chemosensory receptors is considered to be typical or ectopic may, however, be merely a point of view yet and depends on the available data. By the same token, biopsy-based investigations on the expression of chemosensory receptor transcripts in any tissue have to be controlled carefully, as every tissue is potentially "contaminated" with blood cells. For instance, a recent next-generation sequencing-based study demonstrated expression of OR transcripts in the eye; however, the only in situ hybridization signals of 1 Class I OR predominantly localized to blood vessels of choroid and retina [76].

TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 dimerize to constitute a functional sweet-taste receptor in taste cells on the tongue [32, 77]. In the present study, several observations support the notion of TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 dimerization in PMN: 1) partially overlapping, confocal laser-scanning, 2-color immunocytochemistry signals for both subunits in nonpermeabilized cells, 2) coimmunoprecipitation of TAS1R2 with TAS1R3 subunits, 3) a similar percentage of antibody-stained and saccharin-induced migrated cells, and 4) similar effects of receptor-specific siRNA for both receptor subunits. However, we achieved a pharmacological intervention of a saccharin-induced PMN migration only at rather low concentrations of lactisole, which is a known sweet-taste antagonist that binds to the TAS1R3 subunit of the sweet-taste receptor heterodimer [77]. Strikingly, in the present study, the TAS1R3 subunit appeared to be necessary and sufficient to mediate a gustducin-dependent PMN migration toward lactisole itself, adding to the notion that lactisole interacts with TAS1R3 and suggesting lactisole as an agonist for TAS1R3 homomers signaling via gustducin, at least in PMN. A TAS1R3 homomer function has been suggested recently in 3T3-L1 cells [78].

The high abundance of RNA for bitter receptors TAS2R43 and TAS2R31 in blood leukocyte samples was paralleled by high relative RNA expression levels, e.g., in PMN. This may underline their importance for detecting potential poisonous substances, e.g., aristolochic acid, with high sensitivity in the nanomole/L range [70]. Notably, the TAS2R43 ortholog in the cow showed the highest relative RNA expression in PMN among all bovine TAS2Rs.

Interestingly and across chemosensory modalities, the expression of TAS1R2 or TAS1R3 largely overlapped with that of ORs (or TAAR1), on average, in 49% or 44% of PMN, respectively, which is quite similar to the, on average, 37% of cells that coexpressed TAS2R and OR. Notably, in our study, the expression of chemosensory receptors in leukocytes was paralleled by the mRNA expression of some of the canonical signaling components, such as Gα-gustducin, which belongs to the Gi-type family of G proteins, and Gα-olf, at least in PMN. 2-PEA, which is a known agonist for biogenic amine receptors with an olfactory function, in the present study, activated migration in a similar percentage of ∼60% of PMN, as has been described to be TAAR1 and TAAR2 dependent in our previous study [22]. In a similar percentage of PMN, 2-PEA or saccharin activated chemotactic migration, which was largely attenuated by PTX or by siRNA knockdown of α-gustducin, suggesting a role of at least Gi-type proteins in the activation of chemotactic migration by physiologic concentrations of these foodborne chemosensory receptor agonists. Indeed, the plasma concentrations of 2-PEA have been published to be in the nanomolar range [79], and plasma concentrations for saccharin were published to be in the micromolar range after typical sweetener application [11, 80]. Consequently, olfactory and taste receptors, as well as their signaling components, may be considered markers for, on average, 40–60% of circulating PMN, constituting a chemosensory-type subset of PMN, which remains to be characterized by future experiments, for instance, by use of receptor-specific antibodies suitable for use in flow cytometry. There is, indeed, a growing body of evidence for functional PMN subsets [81–88].

What could be the function of a chemosensory-type subset of PMN? The functional role of olfactory and taste receptors in leukocytes remains to be elucidated by future experiments and, at least in the case of OR, will require better knowledge of receptor-specific agonists. However, we hypothesize that chemosensory subsets of leukocytes with high plasticity [89] may enable our cellular immune system to detect specifically foodborne flavor compounds and react to food uptake by postprandially responding to the same foodborne aroma chemicals that our chemosensory systems—olfaction and taste—encountered preprandially. A gut-associated lymphoid tissue that warrants immune sensing of foodborne aroma chemicals would be, e.g., the Peyer’s patches of the ileum, which harbor a variety of leukocytes [90]. Here, chemosensory-type leukocytes may reside at much higher percentages, as compared to the percentages observed in circulating blood in the present study. In general, it may be beneficial, for instance, to have a food ingredient-alerted cellular immune system, as food potentially may be contaminated by, e.g., pathogens or toxic substances. For instance, it has been shown recently in mice that dietary fish oil increased the proportion of a specific circulating PMN subpopulation following endotoxin administration [17].

Different food and food ingredients, however, may differentially affect immune cells’ functions, for instance, via regulation of their cognate receptors. Chemosensory receptor expression patterns and functions in blood leukocytes may, thus, be highly individualized. Our observation of large variations of chemosensory receptor expression across different blood leukocytes and individual blood samples corroborates this notion. Regulation of receptor expression and signaling is a common feature among GPCRs [91, 92] and recently, has been suggested for few OR expressed in PBMCs [48], as well as for some bitter-taste receptors ectopically expressed in the heart [39]. However, different expression levels may be a result of, e.g., chemosensory receptor gene polymorphisms, such as copy number variations, which have been described, at least for olfactory and taste receptors, in their respective canonical chemosensory organs [93, 94]. At least in the olfactory epithelium, Young et al. [95] reported that transcript levels can differ between olfactory receptors by up to 300-fold.

In summary, here, we show by RT-PCR and RT-qPCR that 96% of human Class I OR genes, all TAS2R genes and TAS1R genes, show differential mRNA expression in 5 types of blood leukocytes but within 1 subset of 1 leukocyte type, largely coexpress in the same cells, as observed for 3 OR, 1 TAAR, 2 TAS2R, and 2 TAS1R proteins in different combinations of 2-color immunocytochemistry experiments. In similar size subsets of, on average, 40–60% of PMN, we observed an immunocytochemical staining of chemosensory receptors, as well as receptor-specific odorant- or tastant-induced chemotactic migration. Altogether, our data suggest the existence of cell type-specific chemosensory-type subpopulations of leukocytes displaying interindividual variations in their equipment with certain olfactory and taste receptors, and furthermore, suggest foodborne flavor chemicals as receptor-specific bioactives on our cellular immune system.

AUTHORSHIP

A.M., M.W.P., and D.K. designed experiments. A.M. isolated human blood leukocytes and RNA; performed RT-PCR and qRT-PCR, as well as PMN chemotaxis and transmigration assays; and analyzed data. I.B. and M.W.P. performed RT-qPCR experiments and analyzed RT-qPCR data. J.F. performed immunocytochemistry experiments, WB, Co-IP, and IB experiments and analyzed data. K.F. validated PCR primers, performed PCR experiments with degenerate primers, and analyzed data. Overall project management was by D.K., A.M., and M.W.P. D.K. prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Kay Schneitz for time with a confocal laser-scanning microscope and to Angela Sachsenhauser for expert technical assistance. A.M., J.F., K.F, and D.K. are grateful for continuous support by Peter Schieberle.

Glossary

- 2-PEA

β-phenylethylamine, 2D = 2-dimensional

- co-IP

coimmunoprecipitation

- Cq

cycle of quantification

- FPR1

formylated peptide receptor 1

- GITC

guanidiniumisothiocyanate

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- IB

immunoblot

- OR

odorant receptor

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PMN

polymorphonuclear neutrophil(s)

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- RT-qPCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TAAR1

trace amine-associated receptor 1

- TAS1/2R

taste receptor family 1/2

- TM

transmembrane region

- TRPM5

transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 5

- TSA

tyramide signal amplification

- WB

Western blot

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kehrl J. H. (2004) G-Protein-coupled receptor signaling, RGS proteins, and lymphocyte function. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 24, 409–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lattin J., Zidar D. A., Schroder K., Kellie S., Hume D. A., Sweet M. J. (2007) G-Protein-coupled receptor expression, function, and signaling in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lira S. A., Furtado G. C. (2012) The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Immunol. Res. 54, 111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M. (2010) Chemokines and their receptors: orchestrating a fine balance between health and disease. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 30, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maslowski K. M., Vieira A. T., Ng A., Kranich J., Sierro F., Yu D., Schilter H. C., Rolph M. S., Mackay F., Artis D., Xavier R. J., Teixeira M. M., Mackay C. R. (2009) Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 461, 1282–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinolo M. A., Ferguson G. J., Kulkarni S., Damoulakis G., Anderson K., Bohlooly-Y M., Stephens L., Hawkins P. T., Curi R. (2011) SCFAs induce mouse neutrophil chemotaxis through the GPR43 receptor. PLoS ONE 6, e21205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böckmann S., Paegelow I. (2000) Kinins and kinin receptors: importance for the activation of leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68, 587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandig H., Pease J. E., Sabroe I. (2007) Contrary prostaglandins: the opposing roles of PGD2 and its metabolites in leukocyte function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81, 372–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward P. A. (2008) Role of the complement in experimental sepsis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83, 467–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Ye D. (2013) Molecular biology for formyl peptide receptors in human diseases. J. Mol. Med. 91, 781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colburn W. A., Bekersky I., Blumenthal H. P. (1981) Dietary saccharin kinetics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 30, 558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Désage M., Schaal B., Soubeyrand J., Orgeur P., Brazier J. L. (1996) Gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric method to characterise the transfer of dietary odorous compounds into plasma and milk. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 678, 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeller A., Horst K., Rychlik M. (2009) Study of the metabolism of estragole in humans consuming fennel tea. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 22, 1929–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addai F. K. (2010) Natural cocoa as diet-mediated antimalarial prophylaxis. Med. Hypotheses 74, 825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh A., Holvoet S., Mercenier A. (2011) Dietary polyphenols in the prevention and treatment of allergic diseases. Clin. Exp. Allergy 41, 1346–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sultan M. T., Butt M. S., Qayyum M. M., Suleria H. A. (2014) Immunity: plants as effective mediators. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 54, 1298–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnardottir H. H., Freysdottir J., Hardardottir I. (2013) Dietary fish oil increases the proportion of a specific neutrophil subpopulation in blood and total neutrophils in peritoneum of mice following endotoxin-induced inflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24, 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomasdottir V., Vikingsson A., Freysdottir J., Hardardottir I. (2013) Dietary fish oil reduces the acute inflammatory response and enhances resolution of antigen-induced peritonitis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24, 1758–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberles S. D. (2009) Trace amine-associated receptors are olfactory receptors in vertebrates. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberles S. D., Buck L. B. (2006) A second class of chemosensory receptors in the olfactory epithelium. Nature 442, 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindemann L., Ebeling M., Kratochwil N. A., Bunzow J. R., Grandy D. K., Hoener M. C. (2005) Trace amine-associated receptors form structurally and functionally distinct subfamilies of novel G protein-coupled receptors. Genomics 85, 372–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babusyte A., Kotthoff M., Fiedler J., Krautwurst D. (2013) Biogenic amines activate blood leukocytes via trace amine-associated receptors TAAR1 and TAAR2. J. Leukoc. Biol. 93, 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babusyte A., Krautwurst D. (2013) Tracing amines to their receptors: a synopsis in light of recent literature. Cell Biol, Res, Ther, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buck L., Axel R. (1991) A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 65, 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mainland J. D., Keller A., Li Y. R., Zhou T., Trimmer C., Snyder L. L., Moberly A. H., Adipietro K. A., Liu W. L., Zhuang H., Zhan S., Lee S. S., Lin A., Matsunami H. (2014) The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olender T., Waszak S. M., Viavant M., Khen M., Ben-Asher E., Reyes A., Nativ N., Wysocki C. J., Ge D., Lancet D. (2012) Personal receptor repertoires: olfaction as a model. BMC Genomics 13, 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunami H., Montmayeur J. P., Buck L. B. (2000) A family of candidate taste receptors in human and mouse. Nature 404, 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandrashekar J., Mueller K. L., Hoon M. A., Adler E., Feng L., Guo W., Zuker C. S., Ryba N. J. (2000) T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100, 703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler E., Hoon M. A., Mueller K. L., Chandrashekar J., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2000) A novel family of mammalian taste receptors. Cell 100, 693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi P., Zhang J., Yang H., Zhang Y. P. (2003) Adaptive diversification of bitter taste receptor genes in mammalian evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson G., Chandrashekar J., Hoon M. A., Feng L., Zhao G., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2002) An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 416, 199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson G., Hoon M. A., Chandrashekar J., Zhang Y., Ryba N. J., Zuker C. S. (2001) Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 106, 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breslin P. A. (2013) An evolutionary perspective on food and human taste. Curr. Biol. 23, R409–R418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunkel A., Steinhaus M., Kotthoff M., Nowak B., Krautwurst D., Schieberle P., Hofmann T. (2014) Nature’s chemical signatures in human olfaction: a foodborne perspective for future biotechnology. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 7124–7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui T., Tsolakis A. V., Li S. C., Cunningham J. L., Lind T., Oberg K., Giandomenico V. (2013) Olfactory receptor 51E1 protein as a potential novel tissue biomarker for small intestine neuroendocrine carcinomas. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 168, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deshpande D. A., Wang W. C. H., McIlmoyle E. L., Robinett K. S., Schillinger R. M., An S. S., Sham J. S. K., Liggett S. B. (2010) Bitter taste receptors on airway smooth muscle bronchodilate by localized calcium signaling and reverse obstruction. Nat. Med. 16, 1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feldmesser E., Olender T., Khen M., Yanai I., Ophir R., Lancet D. (2006) Widespread ectopic expression of olfactory receptor genes. BMC Genomics 7, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flegel C., Manteniotis S., Osthold S., Hatt H., Gisselmann G. (2013) Expression profile of ectopic olfactory receptors determined by deep sequencing. PLoS ONE 8, e55368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster S. R., Porrello E. R., Purdue B., Chan H. W., Voigt A., Frenzel S., Hannan R. D., Moritz K. M., Simmons D. G., Molenaar P., Roura E., Boehm U., Meyerhof W., Thomas W. G. (2013) Expression, regulation and putative nutrient-sensing function of taste GPCRs in the heart. PLoS ONE 8, e64579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goto T., Adjaye J., Rodeck C. H., Monk M. (1999) Identification of genes expressed in human primordial germ cells at the time of entry of the female germ line into meiosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 5, 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwatsuki K., Uneyama H. (2012) Sense of taste in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 118, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee R. J., Kofonow J. M., Rosen P. L., Siebert A. P., Chen B., Doghramji L., Xiong G., Adappa N. D., Palmer J. N., Kennedy D. W., Kreindler J. L., Margolskee R. F., Cohen N. A. (2014) Bitter and sweet taste receptors regulate human upper respiratory innate immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1393–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer D., Voigt A., Widmayer P., Borth H., Huebner S., Breit A., Marschall S., de Angelis M. H., Boehm U., Meyerhof W., Gudermann T., Boekhoff I. (2012) Expression of Tas1 taste receptors in mammalian spermatozoa: functional role of Tas1r1 in regulating basal Ca²⁺ and cAMP concentrations in spermatozoa. PLoS ONE 7, e32354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rozengurt E. (2006) Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. I. Bitter taste receptors and alpha-gustducin in the mammalian gut. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291, G171–G177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spehr M., Schwane K., Riffell J. A., Zimmer R. K., Hatt H. (2006) Odorant receptors and olfactory-like signaling mechanisms in mammalian sperm. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 250, 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas M. B., Haines S. L., Akeson R. A. (1996) Chemoreceptors expressed in taste, olfactory and male reproductive tissues. Gene 178, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feingold E. A., Penny L. A., Nienhuis A. W., Forget B. G. (1999) An olfactory receptor gene is located in the extended human beta-globin gene cluster and is expressed in erythroid cells. Genomics 61, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao W., Ho L., Varghese M., Yemul S., Dams-O’Connor K., Gordon W., Knable L., Freire D., Haroutunian V., Pasinetti G. M. (2013) Decreased level of olfactory receptors in blood cells following traumatic brain injury and potential association with tauopathy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 34, 417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bustin S. A., Benes V., Garson J. A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., Mueller R., Nolan T., Pfaffl M. W., Shipley G. L., Vandesompele J., Wittwer C. T. (2009) The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55, 611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vandesompele J., Kubista M., Pfaffl M. W. (2009) Reference gene validation software for improved normalization. In Real-Time PCR: Current Technology and Applications. (Logan J., Edwards K., Saunders N., eds.). Caister Academic, London, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reynolds A., Leake D., Boese Q., Scaringe S., Marshall W. S., Khvorova A. (2004) Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glusman G., Bahar A., Sharon D., Pilpel Y., White J., Lancet D. (2000) The olfactory receptor gene superfamily: data mining, classification, and nomenclature. Mamm. Genome 11, 1016–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niimura Y., Nei M. (2003) Evolution of olfactory receptor genes in the human genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12235–12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Everts-van der Wind A., Larkin D. M., Green C. A., Elliott J. S., Olmstead C. A., Chiu R., Schein J. E., Marra M. A., Womack J. E., Lewin H. A. (2005) A high-resolution whole-genome cattle-human comparative map reveals details of mammalian chromosome evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18526–18531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee K., Nguyen D. T., Choi M., Cha S. Y., Kim J. H., Dadi H., Seo H. G., Seo K., Chun T., Park C. (2013) Analysis of cattle olfactory subgenome: the first detail study on the characteristics of the complete olfactory receptor repertoire of a ruminant. BMC Genomics 14, 596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X., De la Cruz O., Pinto J. M., Nicolae D., Firestein S., Gilad Y. (2007) Characterizing the expression of the human olfactory receptor gene family using a novel DNA microarray. Genome Biol. 8, R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Go Y.; SMBE Tri-National Young Investigators (2006) Proceedings of the SMBE Tri-National Young Investigators’ Workshop 2005. Lineage-specific expansions and contractions of the bitter taste receptor gene repertoire in vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2014) Gene search tool. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dalton R. P., Lyons D. B., Lomvardas S. (2013) Co-opting the unfolded protein response to elicit olfactory receptor feedback. Cell 155, 321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyons D. B., Allen W. E., Goh T., Tsai L., Barnea G., Lomvardas S. (2013) An epigenetic trap stabilizes singular olfactory receptor expression. Cell 154, 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez I. (2013) Singular expression of olfactory receptor genes. Cell 155, 274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Behrens M., Foerster S., Staehler F., Raguse J. D., Meyerhof W. (2007) Gustatory expression pattern of the human TAS2R bitter receptor gene family reveals a heterogenous population of bitter responsive taste receptor cells. J. Neurosci. 27, 12630–12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zozulya S., Echeverri F., Nguyen T. (2001) The human olfactory receptor repertoire. Genome Biol. 2, RESEARCH0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weizmann Institute of Science. (2011) HORDE: The Human Olfactory Data Explorer. Available at: http://bioportal.weizmann.ac.il/HORDE/.

- 65.Meyerhof W., Batram C., Kuhn C., Brockhoff A., Chudoba E., Bufe B., Appendino G., Behrens M. (2010) The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chem. Senses 35, 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Behrens M., Gunn H. C., Ramos P. C., Meyerhof W., Wooding S. P. (2013) Genetic, functional, and phenotypic diversity in TAS2R38-mediated bitter taste perception. Chem. Senses 38, 475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kolaczkowska E., Kubes P. (2013) Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 159–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Winnig M., Kuhn C., Frank O., Bufe B., Behrens M., Hofmann T., Meyerhof W. (2008) Saccharin: artificial sweetener, bitter tastant, and sweet taste inhibitor. In Sweetness and Sweeteners, Vol. 979, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Galindo-Cuspinera V., Winnig M., Bufe B., Meyerhof W., Breslin P. A. (2006) A TAS1R receptor-based explanation of sweet ‘water-taste’. Nature 441, 354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuhn C., Bufe B., Winnig M., Hofmann T., Frank O., Behrens M., Lewtschenko T., Slack J. P., Ward C. D., Meyerhof W. (2004) Bitter taste receptors for saccharin and acesulfame K. J. Neurosci. 24, 10260–10265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katada T. (2012) The inhibitory G protein G(i) identified as pertussis toxin-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 35, 2103–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cubillos S., Norgauer J., Lehmann K. (2010) Toxins-useful biochemical tools for leukocyte research. Toxins (Basel) 2, 428–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dewan A., Pacifico R., Zhan R., Rinberg D., Bozza T. (2013) Non-redundant coding of aversive odours in the main olfactory pathway. Nature 497, 486–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Milatovich A., Qiu R. G., Grosschedl R., Francke U. (1994) Gene for a tissue-specific transcriptional activator (EBF or Olf-1), expressed in early B lymphocytes, adipocytes, and olfactory neurons, is located on human chromosome 5, band q34, and proximal mouse chromosome 11. Mamm. Genome 5, 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang M. M., Reed R. R. (1993) Molecular cloning of the olfactory neuronal transcription factor Olf-1 by genetic selection in yeast. Nature 364, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pronin A., Levay K., Velmeshev D., Faghihi M., Shestopalov V. I., Slepak V. Z. (2014) Expression of olfactory signaling genes in the eye. PLoS ONE 9, e96435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu H., Staszewski L., Tang H., Adler E., Zoller M., Li X. (2004) Different functional roles of T1R subunits in the heteromeric taste receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 14258–14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masubuchi Y., Nakagawa Y., Ma J., Sasaki T., Kitamura T., Yamamoto Y., Kurose H., Kojima I., Shibata H. (2013) A novel regulatory function of sweet taste-sensing receptor in adipogenic differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. PLoS ONE 8, e54500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miura Y. (2000) Plasma beta-phenylethylamine in Parkinson’s disease. Kurume Med. J. 47, 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pantarotto C., Salmona M., Garattini S. (1981) Plasma kinetics and urinary elimination of saccharin in man. Toxicol. Lett. 9, 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arnardottir H. H., Freysdottir J., Hardardottir I. (2012) Two circulating neutrophil populations in acute inflammation in mice. Inflamm. Res. 61, 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beyrau M., Bodkin J. V., Nourshargh S. (2012) Neutrophil heterogeneity in health and disease: a revitalized avenue in inflammation and immunity. Open Biol. 2, 120134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clemmensen S. N., Bohr C. T., Rørvig S., Glenthøj A., Mora-Jensen H., Cramer E. P., Jacobsen L. C., Larsen M. T., Cowland J. B., Tanassi J. T., Heegaard N. H., Wren J. D., Silahtaroglu A. N., Borregaard N. (2012) Olfactomedin 4 defines a subset of human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 91, 495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fredriksson M. I. (2012) Effect of priming in subpopulations of peripheral neutrophils from patients with chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 83, 1192–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kolaczkowska E., Kubes P. (2012) Phagocytes & granulocytes. Angiogenic neutrophils: a novel subpopulation paradigm. Blood 120, 4455–4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pillay J., Kamp V. M., van Hoffen E., Visser T., Tak T., Lammers J. W., Ulfman L. H., Leenen L. P., Pickkers P., Koenderman L. (2012) A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits T cell responses through Mac-1. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 327–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsuda Y., Takahashi H., Kobayashi M., Hanafusa T., Herndon D. N., Suzuki F. (2004) Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity 21, 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Welin A., Amirbeagi F., Christenson K., Björkman L., Björnsdottir H., Forsman H., Dahlgren C., Karlsson A., Bylund J. (2013) The human neutrophil subsets defined by the presence or absence of OLFM4 both transmigrate into tissue in vivo and give rise to distinct NETs in vitro. PLoS ONE 8, e69575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Galli S. J., Borregaard N., Wynn T. A. (2011) Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jung C., Hugot J. P., Barreau F. (2010) Peyer’s patches: the immune sensors of the intestine. Int. J. Inflamm. 2010, 823710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Comerford I., Harata-Lee Y., Bunting M. D., Gregor C., Kara E. E., McColl S. R. (2013) A myriad of functions and complex regulation of the CCR7/CCL19/CCL21 chemokine axis in the adaptive immune system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 24, 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tomankova H., Myslivecek J. (2011) Mechanisms of G protein-coupled receptors regulation. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 32, 607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Roudnitzky N., Bufe B., Thalmann S., Kuhn C., Gunn H. C., Xing C., Crider B. P., Behrens M., Meyerhof W., Wooding S. P. (2011) Genomic, genetic and functional dissection of bitter taste responses to artificial sweeteners. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3437–3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Young J. M., Endicott R. M., Parghi S. S., Walker M., Kidd J. M., Trask B. J. (2008) Extensive copy-number variation of the human olfactory receptor gene family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 228–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Young J. M., Shykind B. M., Lane R. P., Tonnes-Priddy L., Ross J. A., Walker M., Williams E. M., Trask B. J. (2003) Odorant receptor expressed sequence tags demonstrate olfactory expression of over 400 genes, extensive alternate splicing and unequal expression levels. Genome Biol. 4, R71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]