Abstract

Introduction

Clinical experience suggests that some radical prostatectomy (RP) patients have unrealistic expectations with regard to their long-term sexual function. This study was undertaken to assess the understanding of patients who had previously undergone RP with regard to their postoperative sexual function.

Methods

Patients presenting within 3 months of their RP (open and robotic) were questioned regarding the sexual function information that they had received pre-operatively. Patients were questioned about erectile function, postoperative ejaculatory status, orgasm and postoperative penile morphology changes. Statistical analyses were performed to assess for differences between patients who underwent open versus robotic RP.

Results

336 consecutive patients (from 9 surgeons) with a mean age of 64±11 years had the survey instrument administered (216 underwent open and 120 underwent robotic RP). No significant differences existed in patient age or comorbidity profiles between the two groups. Only 38% of men had an accurate recollection of their nerve sparing status. The mean (SD) elapsed time post-RP at the time of postoperative assessment was 3 (2) months. Robotic RP patients expected shorter EF recovery time (6 vs 12 months, p=0.02), a higher likelihood of recovery back to baseline erectile function (75 vs. 50%, p=0.01), and lower potential need for ICI (4 vs. 20%, p=0.01). Almost half of all patients were unaware that they were rendered anejaculatory by their surgery. None of the robotic RP patients and only 10% of open RP patients recalled being informed of the potential for penile length loss (p<0.01) and none were aware of the association between RP and Peyronie’s disease.

Conclusions

Patients who have undergone RP have largely unrealistic expectations with regard to their postoperative sexual function.

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer has a lifetime risk of diagnosis and death of 1 in 6 and 1 in 34, respectively. With the advent of PSA screening there has been a profound stage migration, which has resulted in over 90% of patients having clinically localized cancer at the time of diagnosis. There are multiple management options for patients with organ-confined disease, including active surveillance, as well as the potentially curative options of radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation therapy, cryotherapy and high-intensity focused ultrasonography1,2.

Despite refinements in each of these techniques, sexual dysfunction remains common after treatment including erectile dysfunction (ED), changes in orgasm and penile morphology. The incidence of these problems varies depending upon the definition used as well as the timing and method of patient assessment after definitive treatment. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) was employed in 63% of all RPs performed in the United States in 2007 and 80% in 2008, and 86% in 20092. According to another study published in 2012 investigating current trends in radical prostatectomies in the United States; only 8% of patients were treated with robotic radical prostatectomy in 2004 while 67% underwent that procedure in 20101. This rise in popularity is largely attributed to marketing rather than the existence of any evidence proving that the robotic approach to RP has improved oncologic or functional outcomes over other surgical approaches.

Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy (RP) is an important quality of life problem. It is our clinical experience that patients who undergo RP often have unrealistic expectations regarding their long-term sexual function. ED has been found to have the a significant negative impact on quality of life in RP patients although no analysis of the impact of orgasm changes, climacturia or penile morphological changes has been conducted.

The majority of patients do not achieve penetration hardness erectile rigidity with PDE5i in the first 6 months after RP and thus most are faced with a decision regarding intracavernosal injection therapy (ICI). Several reports in the literature have highlighted that up to 70% of men have documented penile length loss4–7. Furthermore, a significant proportion of men develop Peyronie’s disease following RP7–8.

Previous studies have shown that the perceptions of urologists and the expectations of the patients do not necessarily concur. A study from France demonstrated that by 2 months after RP, 73% of French patients were frustrated by their ED9. Furthermore, Schroeck et al showed that the regret level after RP was high and that it appeared to be higher after robotic RP10. The authors suggested that this was related to the heightened expectations of patients utilizing this approach.

Our study was undertaken in an effort to assess the understanding of patients who underwent RP with regard to their postoperative sexual function.

METHODS

Study Population

Patients presenting within three months of open or robotic RP to the sexual medicine clinic at our center were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their sexual function expectations. Prostate cancer, demographic and comorbidity data was obtained from the patients’ medical records (Table 1). Specific attention was paid to the type of RP patients had undergone, specifically whether it was an open or robot-assisted approach. Patients were excluded if they had neoadjuvant therapies (androgen deprivation, radiation) or had PSA elevation by the time they were seen postoperatively.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Parameter | Open n=216 |

RALP n=120 |

p Value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) patient age (years) | 65 (14) | 62 (10) | 0.14 | |

| Partnered (%) | 86 | 82 | 0.22 | |

| Mean (SD) partner age (years) | 62 (13) | 61 (17) | 0.11 | |

| Comorbidity status (%) | 1 VRF | 32 | 29 | 0.09 |

| 2 VRF | 36 | 41 | 0.17 | |

| ≥3 VRF | 12 | 7 | 0.087 | |

| Sexual activity (mean (SD) # episodes per month)* | Self | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.073 |

| Partner | 3.2 (2.6) | 2.9 (2.8) | 0.10 | |

| Ability to have sexual intercourse (%) | 88 | 91 | 0.09 | |

VRF: Vascular Risk Factor

NS: not significant

Sexual activity prior to diagnosis of prostate cancer;

Comparing open and robotic prostatectomy patients

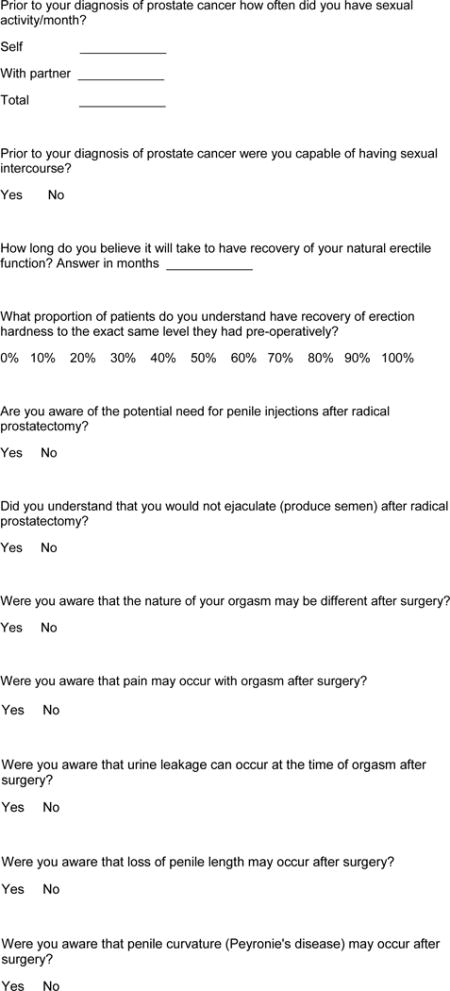

Expectations Assessment

The patients were administered a proprietary questionnaire to assess their understanding of alterations in and recovery of various aspects of their sexual function after RP (Appendix 1). The questionnaire included questions on erectile function (expected time to full recovery of erections, requirement for postoperative intracavernosal injections; Table 2), postoperative ejaculatory status andorgasm (presence, intensity, pain, and climacturia; Table 3), and postoperative Peyronie’s disease, and penile length changes (Table 4).

Table 2.

Expectations Regarding Erectile Function

| Open | Robotic | p Value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recollection as to the mean time to recovery of functional erections (months) | 12 | 6 | 0.02 |

| Recollection as to the mean proportion of patients having recovery of EF to baseline level (%) | 50 | 75 | 0.01 |

| Recollection of being told of the potential for the need to use intracavernosal injections (%) | 20 | 4 | 0.01 |

Comparing open and robotic prostatectomy patients

Table 3.

Expectations Regarding Ejaculation and Orgasm

| Open | Robotic | p Value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recollection of anejaculatory status (%) | 70 | 60 | 0.065 |

| Recollection of potential for change in nature of orgasm (%) | 10 | 12 | 0.09 |

| Recollection of potential for orgasmic pain (%) | 2 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Recollection of potential for climacturia (%) | 2 | 0 | 0.15 |

Comparing open and robotic prostatectomy patients

Table 4.

Expectations Regarding Penile Morphology

| Open | Robotic | p Value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recollection of potential for penile length loss (%) | 10 | 0 | <0.01 |

| Knowledge of an association between RP and Peyronie’s disease (%) | 0 | 0 | NS |

Comparing open and robotic prostatectomy patients

Statistics

Patients were separated by type of RP, open versus robot–assisted. Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess for differences between open and robotic RP patients.

RESULTS

Study Population

Information on patient demographics is displayed in Table 1. The study population included 336 consecutive patients, of whom 216 had open and 120 had robotic RP. The surgeries were performed by 9 different surgeons (4 open surgeons, 3 robot surgeons, and 2 surgeons who offered both procedures). The mean elapsed time post-RP at the time of sexual medicine clinic presentation was 3±2 months. Self-referred patients accounted for 22% of the study population. The mean patient age was 64±11 years, with no significant difference between the open and robotic groups. The percentage of patients with a partner was not significantly different between the open (86%) and robotic (82%) groups nor was the mean (SD) partner age at 62 (13) years for the open group and 61 (17) for the robotic group. There was no significant difference in comorbidity status between the two groups or in pathologic stage. Preoperatively, 88% and 91% of open and robotic patients respectively reported erections sufficient for sexual intercourse (p=0.13).

Expectations

Only 38% of patients had an accurate recollection of their nerve sparing status. Results of the sexual function knowledge assessment are listed in the Tables 2, 3 and 4. Patient knowledge regarding post-RP sexual function was poor with significant differences between the open and the robotic RP groups. Robotic RP patients expected shorter EF recovery time (6 vs 12 months, p=0.02), a higher likelihood of recovery back to baseline erectile function (75 vs 50%, p=0.01), and lower potential need for ICI (4 vs 20%, p=0.01).

With regards to expectations regarding ejaculation and orgasm, only 70% of open and 60% of robotic RP patients were aware that they were rendered anejaculatory by their surgery (p=0.065). Few, if any, patients in either group were aware of the potential for change in nature of orgasm (p=0.09), orgasmic pain (0.2), or climacturia (p=0.15). None of the robotic RP patients and only 10% of open RP patients recalled being informed of the potential for penile length loss (p<0.01). No patients were aware of the recently-described association between RP and Peyronie’s disease.

DISCUSSION

Patients who have undergone radical prostatectomy have unrealistic expectations with regard to postoperative sexual function. In particular, a significant proportion of patients are unaware of the inability to ejaculate, and almost none understand that there are documented orgasm changes or the association between RP and Peyronie’s disease8. Patients undergoing robotic RP are less likely to be aware of the potential need for ICI therapy after surgery or the link between RP and penile length changes, and are more likely to think their erectile function will recover within the first 12 months postoperatively.

Shroeck et al applied a multivariate logistic regression model to a group of 400 patients treated with either open or laparoscopic radical prostatectomy between 2000–2007. The response rate for the survey was 61% with 84% of patients satisfied with their treatment and 19% of these patients regretting their choice of treatment based on previously validated five-level Likert items. Independent predictors of patient satisfaction included lower income (odds ratio [OR], 0.08; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03–0.23), shorter follow-up (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41–0.98), having undergone open versus robotic-assisted laparoscopic RP (OR, 4.45; 95% CI, 1.90–10.4)], urinary domain scores (OR, 2.70; 95% CI, 1.60–4.54), and hormone domain scores (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.30–3.12). The authors hypothesized that robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy was associated with a higher rate of regret and dissatisfaction mainly because of higher expectations associated with a newer, more “innovative”, procedure10.

Another study published by Hu et al found that minimally-invasive radical prostatectomy, whether robot-assisted or purely laparoscopic, was associated with an increased risk of genitourinary complications (4.7% vs 2.1%; p = 0.001) and diagnoses of incontinence (15.9 vs 12.2 per 100 person-years; p = 0.02) and ED (26.8 vs 19.2 per 100 person-years; p = 0.009) despite shorter length of hospital stay, and lower rates of short-term complications and strictures11.

In a survey of 349 patients who had chosen different treatment modalities for prostate cancer, Clark et al found that 24% felt that they were poorly informed and 16% regretted their decision12. A study by Davison et al found that men who played active or collaborative roles in deciding whether to undergo RP had lower scores of decision regret when compared to those who took on passive roles13.

In the field of vascular surgery, a study by Lloyd et al evaluated the level of understanding and recall of 71 patients awaiting carotid endarterectomy (CEA). One month after initial consultation patients had unrealistic expectations of the potential benefits of CEA. Many patients believed that the procedure would alleviate other problems such as dizziness, weakness, shortness of breath, poor memory, and difficulty walking, despite never being counseled that this was the case14.

Crawford et al reported a disparity in physician and patient recall of discussions surrounding treatment options and outcomes following a diagnosis of prostate cancer. One hundred percent of physicians surveyed claimed to always discuss treatment-related side-effects whereas only 16% of patients recalled being provided with such information. Additionally, 100% of physicians felt they had addressed patient concerns about ED, the possibility of decreased libido with therapy, and the impact of therapy on quality of life, whereas only 26%, 28%, and 30% of patients surveyed felt that these issues had been adequately addressed15. While this paper was published more than a decade ago, there is little reason to expect that these figures would be any different now. Indeed, the Crawford findings agree supported by our own data.

Mirkin et al, found in their study searching direct-to-consumer internet marketing of robotic radical prostatectomy that many internet sites claimed benefits that were unsupported by evidence and 42 percent of the sites failed to mention risks16.

The strengths of this study are that it included a significant number of men enrolled consecutively and used a standardized, albeit non-validated, instrument for all patients. The limitations include the absence of an instrument to define expectations, our inability to differentiate between what patients were told and what patients remember and the inability to define if some patients did their own research before or after they had seen their surgeon prior to their RP.

These data ate illuminating and should give us reason to think about our approach to the education of the patient prior to RP. Irrespective of whether we as clinicians routinely have a sexual dysfunction discussion or not, patients are not remembering or appreciating the information the way that it is intended and undertake the operation with poor expectations regarding multiple domains of sexual health. The concerns are further amplified for patients undergoing robot assisted RP, our data being confirmatory of the Schroeck data. Further analysis of these data is warranted and ongoing analysis is aimed at defining inter-surgeon variability in the delivery of realistic expectations to patients undergoing RP.

CONCLUSIONS

Disclosure does not equate to understanding. The lack of knowledge is likely multi-factorial in nature. Surgeons should be encouraged to be thorough in counseling patients prior to RP and to document that such discussion is held. Indeed, we go one step further and encourage all clinicians to utilize written instructions to transmit sexual health information to patients, lest they receive the orally transmitted information in a state of anxiety where failure to process the information may be highly likely.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: P30 CA008748

Appendix 1: Survey of Post-Prostatectomy Sexual Function Expectations

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed

References

- 1.Lowrance WT, Eastham JA, Savage C, Maschino AC, Laudone VP, Dechet CB, Stephenson RA, Scardino PT, Sandhu JS. Contemporary open and robotic radical prostatectomy practice patterns among urologists in the United States. J Urol. 2012;187:2087–92. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs BL, Zhang Y, Schroeck FR, et al. Use of advanced treatment technologies among men at low risk of dying from prostate cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6882. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briganti A, Fabbri F, Salonia A, et al. Preserved postoperative penile size correlates well with maintained erectile function after bilateral nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2007;52:702. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gontero P, Galzerano M, Bartoletti R, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of penile shortening after radical prostatectomy and the role of postoperative sexual function. J Urol. 2007;178:602. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munding MD, Wessells HB, Dalkin BL. Pilot study of changes in stretched penile length 3 months after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology. 2001;58:567. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savoie M, Kim SS, Soloway MS. A prospective study measuring penile length in men treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:1462. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000053720.93303.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciancio SJ, Kim ED. Penile fibrotic changes after radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2000;85:101. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tal R, Heck M, Teloken P, Siegrist T, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP. Peyronie’s disease following radical prostatectomy: incidence and predictors. J Sex Med. 2010 Mar;7(3):1254–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chartier-Kastler E, Amar E, Chevallier D, et al. Does management of erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy meet patients’ expectations? Results of a national survey (REPAIR) by the French Urological Association. J Sex Med. 2008;5:693. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeck FR, Krupski TL, Sun L, et al. Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2008;54:785. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu JC, Gu X, Lipsitz SR, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Minimally Invasive vs Open Radical Prostatectomy. JAMA. 2009;302:1557. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3777. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison BJ, So AI, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life, sexual function and decisional regret at 1 year after surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100:780. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd A, Hayes P, Bell PR, et al. The role of risk and benefit perception in informed consent for surgery. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:141. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford ED, Bennett CL, Stone NN, et al. Comparison of perspectives on prostate cancer: analyses of survey data. Urology. 1997;50:366. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirkin JN, Lowrance WT, Feifer AH, Mulhall JP, Eastham JE, Elkin EB. Direct-to consumer Internet promotion of robotic prostatectomy exhibits varying quality of information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:760–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]