Abstract

Olefin chemistry, through pericyclic reactions, polymerizations, oxidations, or reductions, plays an essential role in the foundation of how organic matter is manipulated.1 Despite its importance, olefin synthesis still largely relies upon chemistry invented more than three decades ago, with metathesis2 being the most recent addition. Here we describe a simple method to access olefins with any substitution pattern or geometry from one of the most ubiquitous and variegated building blocks of chemistry: alkyl carboxylic acids. The same activating principles used in amide-bond synthesis can thus be employed, under Ni- or Fe-based catalysis, to extract CO2 from a carboxylic acid and economically replace it with an organozinc-derived olefin on mole scale. Over sixty olefins across a range of substrate classes are prepared, and the ability to simplify retrosynthetic analysis is exemplified with the preparation of sixteen different natural products across a range of ten different families.

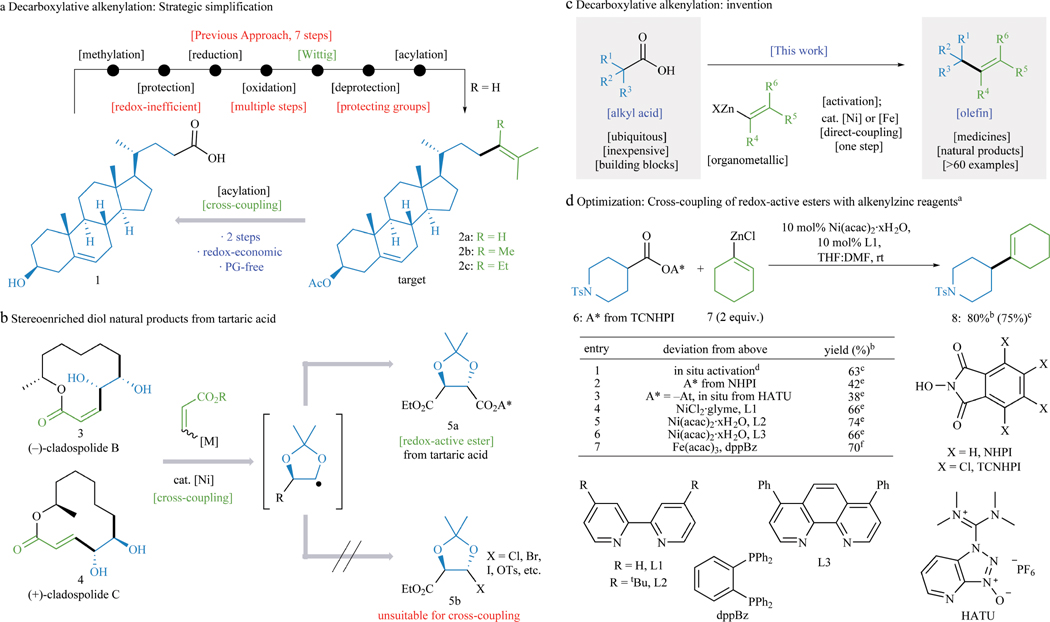

An analysis of available routes to olefin-containing sterol acetate 2a points to retrosynthetic deficiencies that still exist in the modern era (Figure 1A). Seven conventional steps are required to convert steroid derivative 1 to 2a,3 only one of which forms a strategic C–C bond. The entire strategy is built around the Wittig transform4 which requires redox-adjustment of the free carboxylate to the aldehyde, necessitating protecting group manipulations. By this route only steroid 2a is accessible as related methyl and ethyl-containing sterol acetates (2b, 2c) would require more complex designs. This inefficient sequence is a well-recognized problem that has yet to be solved despite the obvious attraction of a hypothetical method that would directly convert acylated 1 to 2a.

Figure 1. Development of Ni– and Fe–catalyzed decarboxylative alkenylation.

a, Conventional route to sterol acetates (2a–c). b, Utilization of previously unavailable electrophiles in cross-coupling reactions. c, Decarboxylative alkenylation presents a potential solution. d, Optimization of decarboxylative alkenylation. a0.1 mmol. bYield by 1H NMR with CH2Br2 internal standard. c0.25 mmol scale, isolated. d1.1 equiv. TCNHPI, 1.1 equiv. DIC, CH2Cl2 (0.2 M). e20 mol% [Ni] and L, 3.0 equiv. alkenylzinc. f10 mol% [Fe], 12 mol% dppbz, 1.5 equiv. dialkenylzinc. See Supporting Information for additional details.

Whereas olefins have the most richly developed reactivity and highest abundance (via the petrochemical industry), the diversity of alkyl carboxylic acid building blocks available is unmatched. If the aforementioned versatile olefin-based cross-coupling partners could be employed in decarboxylative cross-coupling,5–10 novel synthetic pathways could be accessed. For example (Figure 1B), one could envisage the total synthesis of diol-containing natural products such as 3 and 4 as arising from tartaric acid, perhaps the most inexpensive chiral building block available. This new disconnection could only be conceived in a decarboxylative fashion as the corresponding tartrate halides do not exist, and if they did, would most certainly not be stable.

Herein the invention of a general, scalable, chemoselective method for decarboxylative alkenylation is presented that exhibits broad scope across a range of both olefin (from mono- to fully-substituted) and carboxylic acid (1° and 2°) coupling partners (>60 examples, Figure 1C). Decarboxylative alkenylation dramatically simplifies retrosynthetic analysis.11 To demonstrate this fact, total syntheses of sixteen natural products across ten different natural product families spanning a range of steroids, polyketides, vitamins, terpenes, fragrances, and prostaglandins are reported and directly compared to prior art (see Methods for more information).

The optimization of decarboxylative alkenylation is briefly summarized in Figure 1D. In general, the reaction proceeded smoothly when employing the tetrachloro-N-hydroxyphthalimide (TCNHPI, commercially available) esters, an inexpensive Ni(II) source, and the abundant ligand 2,2′-bipyridine (bipy, L1). Using piperidine-derived redox-active ester (RAE) 6, cyclohexenylation could be achieved at room temperature with 10 mol% of Ni(acac)2·xH2O, 10 mol% bipy, and 2.0 equiv. of alkenylzinc reagent 7 to furnish olefin 8 in 75% isolated yield. As has been demonstrated in prior work,5–7 the RAE could also be generated in situ (entry 1) without any purification or even solvent removal. TCNHPI appears to be the optimal RAE (entries 2–3), and Ni(acac)2·xH2O proved superior to the more air- and moisture-sensitive NiCl2·glyme (entry 4). In general, most common solvents were tolerated in this reaction (see SI for details). Alternative ligands were also screened, and L1 was chosen as it is the least expensive (entries 5–6). Finally, as will be shown in several cases, the Fe-based catalytic system developed previously for RAE-cross-coupling7,12,13 could be employed as well (entry 7).

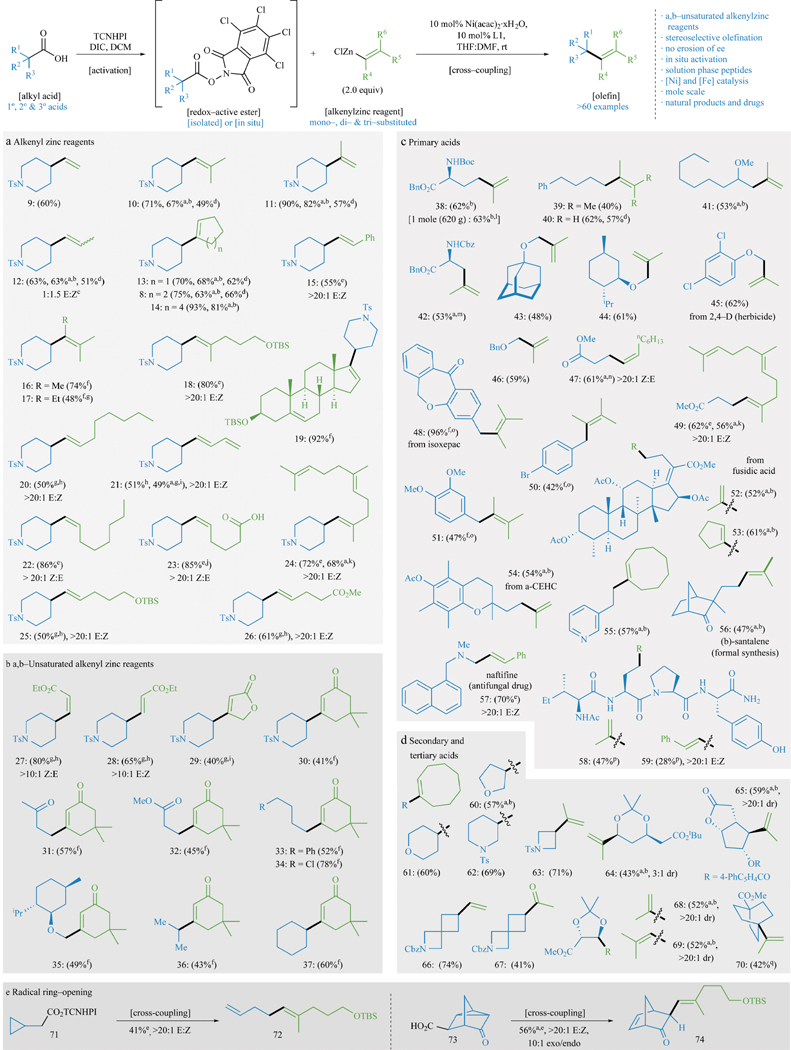

The scope of this new decarboxylative alkenylation reaction is striking as all possible classes of olefin coupling partners could be employed with exquisite control of olefin geometry. The scope of alkenylzinc reagents that can be employed in this coupling are exemplified in Panels A and B of Figure 2. Simple mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted olefins are easily accessible (9–12, 16, 17). From a strategic perspective, the cycloalkenyl products (8, 13–14) would be challenging to make in a more direct way from either the same starting material or even a piperidone. Selecting which method to use when constructing an olefin (e.g. Wittig or metathesis) is usually linked to the underlying mechanism of the process to enable production of the desired stereochemistry of the newly formed olefin. Decarboxylative alkenylation divorces the C–C bond forming event from such stereochemical concerns. As such, conventional techniques can be used to dial in the precise E or Z geometry of an alkenyl-organometallic which can then be employed without any isomerization. For example, olefin 12 is produced as a 1:1.5 mixture of E/Z isomers because the starting commercial Grignard reagent from which it was derived exists as a mixture. Similarly, styrenyl derivative 15 could be procured with high geometrical purity (>20:1 E/Z) as controlled by the starting alkenylzinc species (derived from lithium-halogen exchange of the corresponding styrenyl iodide). The power of stereocontrolled alkyne carbometallation14 can be coupled with this method to produce geometrically pure alkenyl iodides. Alkenylzinc reagents derived therefrom (lithium-halogen exchange/transmetallation) afford tri-substituted olefin products such as 18 and 24 that would be otherwise challenging to make in a single step (in situ RAE) with complete stereopurity. One-pot alkyne hydrozirconation/transmetallation15 can also be employed to access stereodefined E-olefins such as 20, 25, and 26. Despite the presence of low-valent Ni-species, butadiene-containing products such as 21 do not inhibit the reaction, and the E/Z ratio of the starting dienyl species is maintained. Experience from this lab has taught that cross-couplings at the D-ring of a steroid can be challenging;16 the formation of 19 from the easily obtained alkenylzinc species bodes well for future applications in such contexts.

Figure 2. Substrate scope of decarboxylative alkenylation.

The carboxylic acid component is shown in blue and the alkenyl zinc reagent is shown in green. Cross-coupling using various alkenyl zinc reagents (a, b) and different primary (c), secondary and tertiary (d) acids evaluated. Yields refer to isolated yields of products after chromatography on SiO2. a in situ activation. b 3 equiv. alkenylzinc. c alkenylzinc derived from commercial Grignard that exists as a mixture of olefin isomers. d 10 mol% Fe(acac)3, 12 mol% dppbz, 1.5 equiv. dialkenylzinc. e 2 equiv. alkenylzinc, 2 equiv. MgBr2·OEt2. f MeCN as solvent. g 60 °C. h 20 mol% Ni/L, 3 equiv. alkenylzinc, 3 equiv. MgBr2·OEt2. i 20 mol% Ni/L, 5 equiv. alkenylzinc, 5 equiv. MgBr2·OEt2. j alkenylzinc derived from OBO-ester; see SI for work up details. k 3 equiv. alkenylzinc, 3 equiv. MgBr2·OEt2. l See SI for details regarding mol-scale reaction. m 4 equiv. alkenylzinc. n 4 equiv. alkenylzinc, 4 equiv. MgBr2·OEt2. o 10 mol% NiCl2·glyme/4,4′-di-tBuBipy. p See SI for details regarding peptide substrates. q 20 mol% Ni/L, 5 equiv. alkenylzinc, NMP.

Pioneering work from the Knochel group17 has provided robust methods for generating vinylogous zinc reagents for use in cross-coupling chemistry. These species could also be used in the decarboxylative sense (Panel B) to furnish a range of functionalized building blocks that may be otherwise challenging to access. Both cis and trans alkenylzinc reagents can be prepared with high geometric purity, leading smoothly to 27 and 28. This method provides a complimentary strategy to olefin cross-metathesis18 to access such structures. It is also worth noting that the butenolide (29) has never been prepared before. Cross-coupling using butenolides, a motif oft found in natural products, as a nucleophile has only been accomplished through a Stille-coupling of the corresponding stannylated species.16 The adducts with dimedone represent an orthogonal pathway to Stork-Danheiser type adducts19 that, in some cases, would not be easily accessed (31, 32, 35). The magnesium bromide diethyl ether complex (MgBr2·OEt2) was found to be an essential additive for reactions with alkenylzinc reagents derived from alkenyl iodides via lithium-halogen exchange, direct zinc insertion of electron-withdrawn α,β-unsaturated alkenyl iodides, and hydrozirconation/transmetallation of terminal alkynes. All alkenylzinc reagents were prepared as documented in the Supporting Information.

Panel C outlines decarboxylative alkenylations using eighteen different primary carboxylic acids, only six of which were not commercially available (41, 52, 54, 56, 57, 58) but very easily prepared. In contrast, significantly fewer of these electrophiles are available as a halide or an alcohol (from which a tosylate or halide could be made) whereas some substrates would be unstable if they were obtainable (43–46, 49, 51). This points again to the undeniable convenience of a cross-coupling that employs readily available starting materials. Amino acid-derived (38, 42), α-oxy (43–46), benzylic (48, 50–51), fusidane-based (52–53), and heterocycle-containing (55) acids could be successfully transformed into olefins of various types. Even peptides (58, 59) with unprotected residues are competent coupling partners under the reaction conditions. Efficient synthesis of naftifine (57), an antifungal pharmaceutical, was accomplished in high yield with excellent selectivity. Amino acid containing substrates showed no base-mediated erosion of ee (38, 42) or epimerization (58, 59), and benzylic acid 50 showed no loss of the aromatic bromide. Similarly, other known coupling partners in low-valent Ni-chemistry20 such as aromatic C–O (48, 51) and C–Cl (45) bonds, and hydrolytically sensitive phenol acetate esters (54) remained untouched. Lewis-basic heteroatoms are tolerated (55, 57), and a formal synthesis of (β)-santalene could be accomplished in short order (addition of MeLi to ketone 56 and elimination leads to the natural product).21

Secondary (60–69) and tertiary bridgehead (70) RAEs can be easily alkenylated, as well, as shown in Panel D. Of note here is that diastereoselective alkenylations can be predictably incorporated into synthesis plans as demonstrated with substrates 64, 65, 68, and 69. Spirocyclic substrates 65 and 66 are of interest to a medicinal chemistry program (Bristol-Myers Squibb), the latter of which highlights how ethylvinyl ether (zincated) can be used in this coupling as an alternative to Grignard/organolithium addition to an ester or Weinreb amide (see SI for further details and comparison). To probe for the intermediacy of radical species in the decarboxylative alkenylation reaction, radical-ring opening experiments (Panel E) were performed with 71 and 73, affording the corresponding ring-opened products 72 and 74, respectively.

Of the 65 substrates depicted in Figure 2, several were also performed with an in situ protocol (especially in such cases where the RAE was not stable) or using an Fe-based system. The SI contains a detailed troubleshooting guide and a graphical user tutorial. The reaction has been field tested at Bristol-Myers Squibb in many different contexts, and the robustness was demonstrated by conducting the reaction of 38 on a mole scale (63% yield, >600 grams, >99% ee, carried out at Asymchem). As a testament to the robustness of this reaction, no significant modifications to the general procedure were necessary when scaling this reaction up from millimole to mole scale. Currently there are not many glaring limitations for this method as one can generally expect a serviceable yield across a range of substrates; there are relatively more limitations in the chemistry of preparing the alkenyl zinc species.

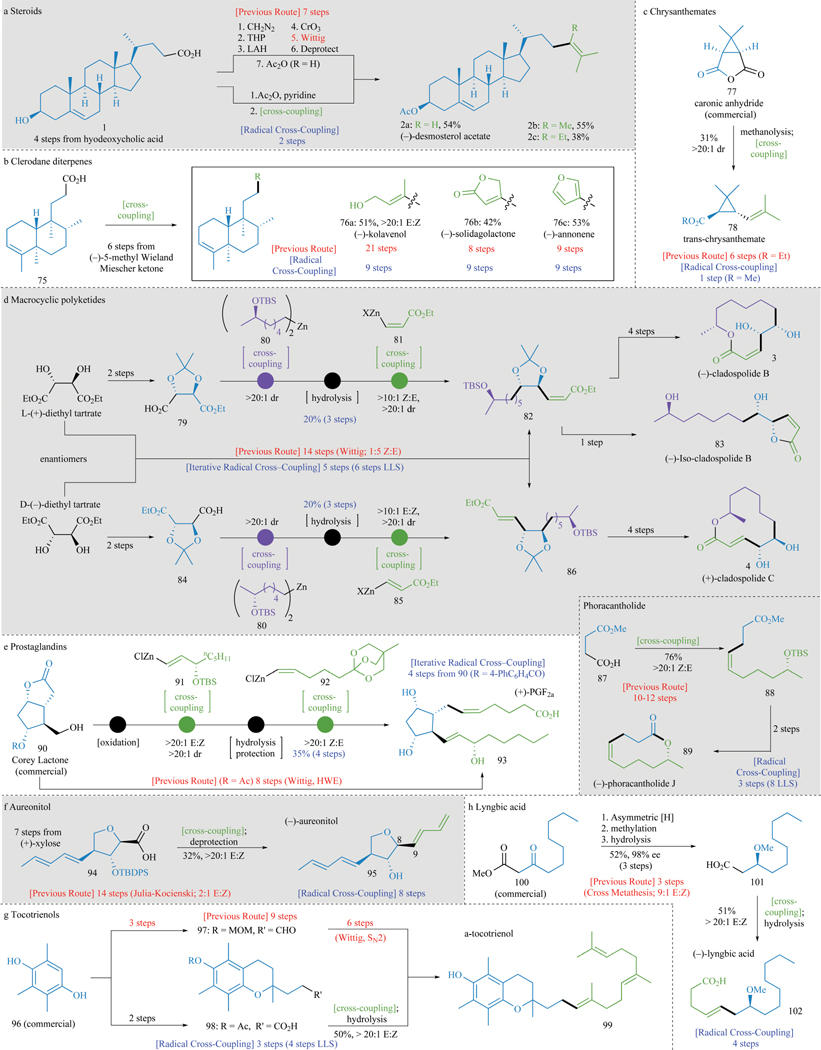

To demonstrate a small snapshot of the vast options that exist to apply this new transformation, Figure 3 summarizes the total synthesis of fifteen different natural products (full details of these sequences can be found in the SI). As mentioned above (Figure 1A), steroidal substrate 2a exemplifies the inefficiency of previous approaches to olefin synthesis as a consequence of chemoselectivity issues surrounding the Wittig reaction and the incorrect oxidation state of the starting material (1). With decarboxylative alkenylation (Figure 3A), the same starting material can be employed and the desired product 2a can be accessed in two steps. Of note is that the current method can be used to make not only 2a but also related natural products that would be otherwise inaccessible (in a direct fashion) such as 2b and 2c.

Figure 3. Total synthesis enabled by decarboxylative alkenylation.

All decarboxylative alkenylations were performed with in situ activation of the carboxylic acid. See SI for full synthetic details and schemes (a–h). LLS = longest linear sequence. [H] = reduction.

The clerodane diterpene family consists of over 650 members that are broadly characterized as having a decalin framework appended to side chains with variegated substituents.22 From a strategic perspective, it would be ideal if a single starting material could be used and divergently converted to multiple family members using a single reaction type. Decarboxylative alkenylation enables the synthesis of the same three natural isolates from 75, a material that is made in 6 steps from readily available (−)-5-methyl Wieland-Miescher ketone. Thus, in only 9 steps from commercially available materials, a simple alkyne, an iodobutenolide, and a bromofuran, served as organozinc precursors that when coupled with 75, enabled access to (−)-kolavenol (76a), (−)- solidagolactone (76b), and (−)-annonene (76c), respectively.

With decarboxylative alkenylation, one can access methyl trans-chrysanthemate (78, Figure 2C) from commercially-available caronic anhydride (77), which after one-pot methanolysis and radical cross-coupling delivers 78 in 31% yield with excellent diastereoselectivity (>20:1).

Many applications of this methodology to polyketide synthesis can be envisaged where the decarboxylative approach allows for innovative uses of classic chiral building blocks in highly convergent ways. For example, tartaric acid is perhaps the cheapest enantiopure chemical that can be purchased (ca $1/mole) and represents an ideal source of the 1,2-diol motif. The total syntheses of (−)-cladospolide B (3), (−)-iso-cladospolide B (83), and (+)-cladospolide C (4) illustrate how both enantiomers of tartaric acid can be used like simple “cassettes” and modularly incorporated to complete syntheses that are not only dramatically shorter than prior approaches but also more selective (Figure 3D). A design based on radical cross-coupling of tartrate derived acids 79 and 84 sets the stage for a triply convergent approach wherein alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling (with alkylzinc reagent 80) precedes decarboxylative alkenylation (with either 81 or 85) to furnish 82 and 86 in only 5 steps with excellent control of olefin geometry. If the steps are counted from alkylzinc reagent 80, the sequence is 6 steps long indicating that the 1,2-diol motif is no longer the bottleneck of the synthesis. This approach is the most direct and inexpensive known. Similarly, monomethyl succinate (87), a commodity chemical, can be coupled to a stereodefined alkenylzinc reagent to furnish 88 directly, which after deprotection and known macrolactonization, delivers (−)-phoracantholide J (89) in only 3 steps (8 steps including the synthesis of the alkenylzinc reagent).

Prostaglandins are classic targets for total synthesis not only due to their intriguing structures and exciting medicinal uses but also because they serve as a veritable proving ground for the development of new methodologies (Figure 3E).23 The commercially-available Corey lactone (90) could be employed in a four step sequence wherein two steps are non-strategic (oxidation and one-pot hydrolysis/protection) and two install the key C–C bonds with the proper olefin geometry. Thus, sequential decarboxylative cross-coupling of E-(91) and Z-(92) alkenylzinc species to the requisite carboxylic acids provides a simple route not only to 93 but is also sufficiently flexible to conceivably access a plethora of new prostaglandin analogs in a combinatorial fashion.

Aureonitol (95) is a tetrahydrofuran-containing natural product discovered in 1979 from Helichrysum aureonitens (Figure 3F).24 A strategic decarboxylative dienylation of 94 delivers 95 in 32% yield with complete selectivity (>20:1 E/Z) as controlled by the chemistry used to fashion the diene nucleophile. Application of this transformation simplifies the synthesis as 94 can be made in 7 simple steps from inexpensive (+)-xylose.25,26

Tocotrienols, members of the vitamin E family, are dietary supplements and have been reported to have an array of beneficial health effects (Figure 3G).27 Current extraction methods from plant materials provide these compounds as a mixture, which is both difficult and costly to separate. Synthesis offers direct access to specific members of the tocotrienol family but contemporary efforts lack selectivity in olefin formation or require concessionary redox manipulations. Trimethylhydroquinone (96) can be employed to furnish 99 with high selectivity (>20:1 E/Z) and in only four steps overall since the farnesyl group can be directly coupled as a single fragment.

Lyngbic acid (102), an inhibitor of quorum sensing in cyanobacteria, was prepared by Noyori asymmetric transfer hydrogenation28 of the commercial β-keto ester 100 followed by decarboxylative cross-coupling delivers 102 with complete selectivity (>20:1 E/Z) in 51% isolated yield (ca. 98% ee).

Methods

Background: Alternative/classical routes to olefins

The vast majority of olefin syntheses commence from other unsaturated systems (e.g. olefin metathesis, Heck coupling, alkyne hydrogenation, etc.), rely on various condensations of carbonyl compounds (Wittig, Peterson, Tebbe, Nysted, Aldol, McMurry, etc), or involve the elimination of an alcohol, amine, or halide.29 Although Negishi, Kumada-Corriu-Tamao, and Suzuki-Miyaura type reactions enable the cross-coupling of olefin-containing organometallic species with alkyl halides with precise control of olefin geometry,30 the limited availability of the latter species diminishes the utility of such a disconnection.31–38

Prior approaches to the total synthesis of natural products

Collectively, Figure 3 represents a selection of great opportunities for organic synthesis as many previously unimaginable pathways open up through the strategic application of this disconnection.

Prior approaches39,40 to the clerodane diterpene natural products target each through a different strategy with, for example, the syntheses of 76a–c ranging from 8–21 steps (Figure 3B).

The naturally occurring insecticide methyl-trans-chrysanthemate (78) has previously been prepared in six steps using a cyclopropanation/Wittig olefination strategy.41,42

Advanced intermediates 82 and 86 have been previously prepared en route to 3–4 and 83 using a Wittig strategy from tartrates that proceeded in 14 steps with 1:5 Z/E olefin selectivity.43 It is worth noting that other approaches to this class of natural products have used olefin-metathesis,44 Evans aldol reaction,45 and Os-catalyzed dihydroxylation46 transforms. (−)-Phoracantholide J (89) was previously constructed through either ring-closing metathesis or Ru-catalyzed hydroalkynylation.47,48

Corey’s 1969 synthesis of (+)-PGF2α (93) and related family members required eight steps from the now commercially available lactone 90 (Corey lactone), with the strategy largely based on the use of two separate olefination steps (Wittg and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons) to install the requisite side chains (colored in green).49 A recent route to (+)-PGF2α was developed by Aggarwal.50

Aureonitol (95, Figure 2F) was previously procured in 14 steps from (S)-serine featuring a non-selective Julia-Kocienski olefination to forge the C8–C9 linkage.51

One reported approach52 to 99 commences with trimethylhydroquinone (96) and employs a Wittig homologation of aldehyde 97 (10:1 E/Z) to install a small fragment of the farnesyl side chain. The remaining C–C bond is fashioned using an SN2 displacement of an alkyl iodide by an alkyl sulfone, thus requiring extra redox and functional group manipulations to afford 99 in nine steps overall.

The simple lipid lyngbic acid (102, Figure 2H), an inhibitor of quorum sensing in cyanobacteria, has previously been made in 3 steps using an olefin cross-metathesis approach (9:1 E/Z) following the enantioselective allylation of an aldehyde using an allyltin reagent (Figure 3H).53

Olefins are ever-present functional groups that are found throughout Nature and every sector of chemical science. Their rich and robust chemistry make them integral to the planning, logic, and reliable execution of multistep synthesis. This operationally simple method harnesses the reliable and programmable synthesis of olefin-containing zinc species and the unparalleled commercial availability and stability of alkyl carboxylic acids to access olefins in a powerful new way. Numerous applications can be anticipated of both this method and the strategy it enables in the contexts of chemoselective fragment coupling (convergent synthesis), homologation (as an alternative to Wittig olefination and related transforms), and stereospecific olefin installation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Department of Defense (NDSEG fellowship to J.T.E.), NIH (GM118176 and F32GM117816 (Postdoctoral Fellowship to L.R.M.)). We thank Dr. D.-H. Huang and Dr. L. Pasternack for assistance with NMR spectroscopy; Professor M. R. Ghadiri for access to preparative HPLC equipment; Dr. M. Schmidt and Dr. E.-X. Zhang for helpful discussions; and M. Yan for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. We are grateful to LEO Pharma for a generous donation of fusidic acid and Professor R. Shenvi for Mn(dpm)3.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J. T. E, R. R. M. and P. S. B. conceived the work; J. T. E., R. R. M., K. S. M., K. W. K., L. R. M., T. Q., B. V., S. A. S., M. D. E., and P. S. B. designed the experiments and analyzed the data; J. T. E., R. R. M., K. S. M., K. W. K., L. R. M., T. Q., B. V. performed the experiments; D.-H. B., F.-L. W., and T. Z. performed mole scale experiments; P. S. B. wrote the manuscript; and J. T. E., R. R. M., K. W. M., K. W. K. assisted in writing and editing the manuscript.

Data availability statement: data generated in this study is available in the supplementary information or on request from the authors.

References

- 1.Smith M. March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure. Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoveyda AH, Zhugralin AR. The remarkable metal-catalysed olefin metathesis reaction. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khripach VA, Zhabinskii VN, Konstantinova OV, Khripach NB, Antonchick AP. Synthesis of 24-functionalized oxysterols. Russ J Bioorganic Chem. 2002;28:257–261. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolaou KC, Härter MW, Gunzner JL, Nadin A. The Wittig and related reactions in natural product synthesis. Liebigs Ann. 1997;1997:1283–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornella J, et al. Practical Ni-catalyzed aryl–alkyl cross-coupling of secondary redox-active esters. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2174–2177. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin T, et al. A general alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling enabled by redox-active esters and alkylzinc reagents. Science. 2016;352:801–805. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toriyama F, et al. Redox-active esters in Fe-catalyzed C–C coupling. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:11132–11135. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan M, Lo JC, Edwards JT, Baran PS. Radicals: reactive intermediates with translational potential. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12692–12714. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huihui KMM, et al. Decarboxylative cross-electrophile coupling of N -hydroxyphthalimide esters with aryl iodides. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5016–5019. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noble A, McCarver SJ, MacMillan DWC. Merging photoredox and nickel catalysis: decarboxylative cross-coupling of carboxylic acids with vinyl halides. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:624–627. doi: 10.1021/ja511913h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey EJ, Cheng X-M. The Logic of Chemical Synthesis. Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatakeyama T, et al. Iron-catalysed fluoroaromatic coupling reactions under catalytic modulation with 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)benzene. Chem Comm. 2009;126:1216–1218. doi: 10.1039/b820879d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedford RB, Huwe M, Wilkinson MC. Iron-catalysed Negishi coupling of benzyl halides and phosphates. Chem Commun. 2009;12:600–602. doi: 10.1039/b818961g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Horn DE, Negishi E. Selective carbon-carbon bond formation via transition metal catalysts.8 Controlled carbometalation Reaction of acetylenes with organoalane-zirconocene dichloride complexes as a route to stereo- and regio-defined trisubstituted olefins. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2252–2254. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart DW, Blackburn TF, Schwartz J. Hydrozirconation. III Stereospecific and regioselective functionalization of alkylacetylenes via vinylzirconium(IV) intermediates. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:679–680. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renata H, et al. Development of a concise synthesis of ouabagenin and hydroxylated corticosteroid analogues. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1330–1340. doi: 10.1021/ja512022r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sämann C, Schade MA, Yamada S, Knochel P. Functionalized alkenylzinc reagents bearing carbonyl groups: preparation by direct metal insertion and reaction with electrophiles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:9495–9499. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu EC, Johnson BM, Townsend EM, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Synthesis of linear (Z)-α,β-unsaturated esters by catalytic cross-metathesis. The influence of acetonitrile. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:13210–13214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stork G, Danheiser RL. Regiospecific alkylation of cyclic. beta.-diketone enol ethers General synthesis of 4-alkylcyclohexenones. J Org Chem. 1973;38:1775–1776. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tasker SZ, Standley EA, Jamison TF. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature. 2014;509:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corey EJ, Hartmann R, Vatakencherry PA. The Synthesis of d,l-β-Santalene and d,l-epi-β-Santalene by stereospecific routes. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:2611–2614. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merritt AT, Ley SV. Clerodane diterpenoids. Nat Prod Rep. 1992;9:243. doi: 10.1039/np9920900243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das S, Chandrasekhar S, Yadav JS, Grée R. Recent developments in the synthesis of Prostaglandins and Analogues. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3286–3337. doi: 10.1021/cr068365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacramento CQ, et al. Aureonitol, a fungi-derived tetrahydrofuran, inhibits influenza replication by targeting its surface glycoprotein hemagglutinin. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moravcová J, Čapková J, Staněk J. One-pot synthesis of 1,2-O-isopropylidene-α-d-xylofuranose. Carbohydr Res. 1994;263:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talekar RR, Wightman RH. Synthesis of some pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine and 1,2,3-triazole isonucleosides. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:3831–3842. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S. Tocotrienols: Vitamin E beyond tocopherols. Life Sci. 2006;78:2088–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noyori R, et al. Asymmetric hydrogenation of beta.-keto carboxylic esters A practical, purely chemical access to .beta.-hydroxy esters in high enantiomeric purity. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5856–5858. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kürti L, Czakó B. Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis: Background and Detailed Mechanisms. Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diederich F, Stang PJ. Metal-catalyzed Cross-coupling reactions. Wiley-VCH; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netherton MR, Fu GC. Nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of unactivated alkyl halides and pseudohalides with organometallic compounds. Adv Synth Catal. 2004;346:1525–1532. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisch AC, Beller M. Catalysts for cross-coupling reactions with non-activated alkyl halides. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:674–688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph A, Lautens M. Secondary alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2656–2670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong H, Gagné MR. Diastereoselective Ni-catalyzed Negishi cross-coupling approach to saturated, fully oxygenated C–alkyl and C–aryl glycosides. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12177–12183. doi: 10.1021/ja8041564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lou S, Fu GC. Enantioselective alkenylation via nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling with organozirconium reagents. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5010–5011. doi: 10.1021/ja1017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J, Fu GC. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of secondary nitriles via stereoconvergent negishi arylations and alkenylations of racemic α-bromonitriles. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9102–9105. doi: 10.1021/ja303442q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi J, Martín-Gago P, Fu GC. Stereoconvergent arylations and alkenylations of unactivated alkyl electrophiles: catalytic enantioselective synthesis of secondary sulfonamides and sulfones. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:12161–12165. doi: 10.1021/ja506885s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatakeyama T, Nakagawa N, Nakamura M. Iron-catalyzed Negishi coupling toward an effective olefin synthesis. Org Lett. 2009;11:4496–4499. doi: 10.1021/ol901555r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piers E, Roberge JY. Total syntheses of the diterpenoids (−)-kolavenol and (−)-agelasine B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:6923–6926. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slutskyy Y, et al. Short enantioselective total syntheses of trans-clerodane diterpenoids: convergent fragment coupling using a trans-decalin tertiary radical generated from a tertiary alcohol precursor. J Org Chem. 2016;81:7029–7035. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devos MJ, Hevesi L, Bayet P, Krief A. A new design for the synthesis of chrysanthemic esters and analogs and for the “pear ester” synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:3911–3914. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devos MJ, Denis JN, Krief A. New stereospecific synthesis of cis and trans d,1-chrysanthemic esters and analogs via a common intermediate. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:1847–1850. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si D, Sekar NM, Kaliappan KP. A flexible and unified strategy for syntheses of cladospolides A, B, C, and iso-cladospolide B. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:6988. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05787a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banwell MG, Loong DTJ. A chemoenzymatic total synthesis of the phytotoxic undecenolide (−)-cladospolide A. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:2050–2060. doi: 10.1039/b401829j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma GVM, Reddy KL, Reddy JJ. First synthesis and determination of the absolute stereochemistry of iso-cladospolide-B and cladospolides-B and C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xing Y, O’Doherty GA. De novo asymmetric synthesis of cladospolide B–D: structural reassignment of cladospolide D via the synthesis of its enantiomer. Org Lett. 2009;11:1107–1110. doi: 10.1021/ol9000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chênevert R, Pelchat N, Morin P. Lipase-mediated enantioselective acylation of alcohols with functionalized vinyl esters: acyl donor tolerance and applications. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:1191–1196. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Avocetien KF, et al. De novo asymmetric synthesis of phoracantholide. J Org Lett. 2016;18:4970–4973. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corey EJ, Weinshenker NM, Schaaf TK, Huber W. Stereo-controlled synthesis of dl-prostaglandins F2 alpha and E2. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:5675–5677. doi: 10.1021/ja01048a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coulthard G, Erb W, Aggarwal VK. Stereocontrolled organocatalytic synthesis of prostaglandin PGF2α in seven steps. Nature. 2012;489:278–281. doi: 10.1038/nature11411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jervis PJ, Cox LR. Total synthesis and proof of relative stereochemistry of (−)-aureonitol. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7616–7624. doi: 10.1021/jo801338t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearce BC, Parker RA, Deason ME, Qureshi AA, Wright JJK. Hypocholesterolemic activity of synthetic and natural tocotrienols. J Med Chem. 1992;35:3595–3606. doi: 10.1021/jm00098a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knouse KW, Wuest WM. The enantioselective synthesis and biological evaluation of chimeric promysalin analogs facilitated by diverted total synthesis. J Antibiot. 2016;69:337–339. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.