Abstract

Background

Previous studies suggest that personality traits play an important role in academic burnout. The aim of this study was to investigate how Cloninger’s temperament and character traits explain academic burnout in a highly competitive environment of medical school.

Methods

A total of 184 Korean medical students participated in the survey. The Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory was measured around the beginning of the semester and Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey at the end of the semester. The correlations and stepwise regression analysis were conducted to explain the association between personality traits and academic burnout. In addition, latent profile analysis and profile analysis were employed to distinguish and explain differences of personality traits among latent academic burnout subgroups.

Results

The higher harm avoidance of temperament and lower self-directedness and cooperativeness of character predicted the subscales of academic burnout in medical students. The Temperament and Character Inventory personality profile of high, middle, and low latent burnout subgroups were significantly different.

Conclusion

This study showed that personality might account for the burnout level in medical education. The importance of character dimension for modulating the effects of temperament traits on academic burnout was discussed for future research.

Keywords: academic burnout, Korean medical students, latent profile analysis, temperament and character

1. Introduction

Medical students are found to have more psychological problems associated with various stressors than those from other academic areas,1, 2 and 80% of their stressors were reported to be related with academic stresses from the competitive environment of medical school.3, 4 When students are exposed to academic stress for a long period, they often express depression, anxiety, aggression, or anger5, 6, 7, 8 and this goes under the influence of physical and psychological burnout accompanying frustration, exhaustion, fatigue, helplessness, and cynical attitude.9, 10

Freudenberger11 who firstly introduced the concept of burnout recognized the importance of personality. Generally speaking, those with high burnout syndrome are characterized as introvert, sensitive, empathetic to others, highly dependent on others’ affection and recognition, and excessively identifying themselves from others.12, 13, 14 Maslach and Jackson of Maslach Burnout Inventory15 also emphasized the significance of personality that interpersonal traits such as intrinsic characteristics and social supports are more fundamental than physical and environmental factors. For example, Jacobs and Dodd16 emphasized the influence of negative temperament on the academic burnout using college students. That is, some experience burnout symptoms, however, others show resilience to it under the same highly stressful circumstances. Therefore, personality variables rather than the extrinsic environments for predicting burnout need to be investigated.

There are many association studies between burnout and personality traits using extroversion,17, 18, 19, 20 openness to experience,21 and neuroticism,20, 21 however scarcity of research regarding the causality between personality and academic burnout is provided. In addition, there are few studies for prevention or intervention for academic stress or burnout focusing on the possibility of personality changes or character development suggested by Cloninger’s biopsychosocial personality model.22 Unlike others, the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) is a personality assessment measuring temperament dimension which determines automatic reactions to external stimuli involving involuntary unconscious processes, along with the character dimension influencing personal and social effectiveness by insight learning about self-concept.22

Temperament dimensions are composed of novelty seeking (NS), harm avoidance (HA), reward dependence (RD), and persistence (PS). NS is a personality trait associated with exploratory excitability in response to novel stimuli, and HA is associated with behavioral inhibition in reaction to dangerous or abhorrent stimuli. RD is a tendency to respond remarkably to signals of social reward, and PS is a tendency to maintain the behavior with intermittent reinforcement. Character dimensions are comprised of self-directedness (SD), cooperativeness (CO), and self-transcendence (ST). SD identifies the self as an autonomous individual, CO understands the self as integral of humanity, and ST considers the self as an integral part of the universe as a whole.

Several studies have investigated the relations between TCI traits and burnout. HA was associated with burnout positively, and SD and CO negatively.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 In addition, NS also predicted the burnout positively and PS negatively.24 It was also reported that those with higher PS and HA are highly vulnerable to burnout.28

Although correlations between personality traits and burnout were revealed in previous studies, researches on the influences of psychological factors explaining its resilience, prevention, and treatment were not satisfactory. Since the temperamental vulnerability to certain mental disorders or psychological burdens were shown to be intervened by character development,22, 29 academic burnout and other related psychological problems could be prevented in advance. Some researchers investigated resilience and treatment on burnout using TCI30, 31 and a wellbeing coaching program enhancing the happiness and wellbeing based on it,32 but it was not suggested for medical education. The psychological and emotional wellbeing of medical students and quality of future doctor–patient relations were reported to be influenced by academic stress and burnout, repeatedly.

For that reason, we examined the effects of temperament and character dimensions on academic burnout including emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy in Korean medical students. Possible causalities between personality traits and academic burnout were investigated with regression analysis and latent profile analysis (LPA). This study would shed a light on the intervention of burnout for efficient and person-centered medical education.

2. Materials

2.1. Participants and procedures

A total of 184 participants of the School of Korean Medicine in Busan metropolitan area were recruited for the present study, and 178 students (90 males and 88 females) completed the Cloninger’s TCI and Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of relevant institution (KMEDIRB2013-01), and all participants provided written informed consent forms for the study. Temperament and character traits were measured at the beginning of the semester and the burnout was measured around the final exam when academic stress and burnout is at the highest level.33

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. MBI-SS

Burnout was measured using the MBI-SS9 which was implemented by Schaufeli et al9 for university students.

The MBI-SS measures three dimensions of burnout with 15 items on a 7-point Likert scale [ranging from never (0) to everyday (6)]. Emotional exhaustion (5 items) and the cynicism (4 items) subscale reflects detachment and distance from the school itself, and efficacy (6 items) subscale is related to both social and nonsocial aspects of academic accomplishments and refers to the individual’s expectations of continued effectiveness at school. In the present study, efficacy scores were transformed into the inefficacy subscale by reverse coding consistent to the original MBI developed by Maslach and Jackson.15 Total burnout is a sum of all three subscales of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy. Cronbach’s alphas for the total burnout, exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy were 0.875, 0.931, 0.908, and 0.852, respectively.

2.2.2. Cloninger’s TCI

Cloninger’s TCI includes two-interrelated domains of temperament and character. Temperament traits reflect biases in automatic responses to emotional stimuli involving involuntary rational processes, whereas character traits depict differences in higher cognitive functions underlying a person’s goals, values, and relationships.22, 34

The temperament dimensions consist of NS (characterized by exploratory excitability, impulsiveness, extravagance, and disorderliness), HA (anticipatory worry, fear of uncertainty, shyness with strangers, and fatigability), RD (sentimentality, openness, attachment, and dependence), and PS (eagerness, work-hardened, ambition, and perfectionism).35

The character dimensions were composed of SD (characterized by purposeful, responsible, resourceful, and self-accepting), CO (empathic, helpful, forgiving, and tolerant), and ST (contemplating, idealistic, spiritual, and transpersonal).

The Korean version of the TCI-Revised-Short (TCI-RS), a 140-item self-report questionnaire, asks individuals to rate each item on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very true). The internal consistencies of NS, HA, RD, PS, SD, CO, and ST were reported as 0.83, 0.86, 0.81, 0.82, 0.87, 0.76, and 0.90, respectively.36

2.3. Statistical analysis

The significance of sex difference was examined with t test in age and subscales of TCI and MBI-SS, and with Chi-square in education level and school years. Pearson correlation analysis was used to establish the relation between subscales of TCI and MBI-SS.

Multiple stepwise regression analyses were conducted to find personality traits explaining subscales of MBI-SS. First, age and sex were introduced (Model 1), and then seven TCI subscale measures were added as the final model (Model 2). The inclusion criterion for entering in the model was p < 0.05 associated with the F-statistic.

LPA was employed to explore the latent subgroups of academic burnout using MPlus 5.21 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, USA).37 The LPA is an empirically driven model derives hidden subgroups of people based on similar characteristics38 from observed continuous variables (e.g., the 3 subscales of MBI-SS). The final number of latent classes is not generally determined prior to analysis the same as the K-means clustering method. While an observation is a number of classes with certainty in the K-means clustering technique, LPA estimates the probability that any observation falls into a class. The number of classes is determined through comparison of posterior fit statistics: models are estimated with classes added repeatedly to determine which model is the best fit to the data until the additional one no longer produced a significant improvement in model fit statistics.

The criteria of model fit are as follows:39 (1) the smaller the Baysian information criterion (BIC) and adjusted BIC, the better the model is; (2) the smaller the p value of Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood difference test (VLMR) or Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood difference test (LMR), the better the model is; and (3) entropy index was used to examine the distinctiveness of latent classes identified, assuming higher than 0.8 as good.40 After determining the number of latent classes, profile analysis was conducted with seven personality factors to elucidate significant differences among extracted latent subgroups from the LPA.

The data are presented as means and standard deviations or frequency as percentage. All analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and MPlus 5.21 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, USA)37 and p values of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 were used for significance.

3. Results

The demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in age (t = 3.626, p < 0.001) between male and female participants, but not in school year [χ2 (3178) = 5.456, p = 0.141] and education level [χ2 (1178) = 0.180, p = 0.671]. The subscales of TCI and MBI-SS are shown in Table 2, and there were no significant differences except ST (t = −2.302, p < 0.05) between male and female.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Male (n = 90) | Female (n = 88) | Total (n = 178) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 30.62 ± 5.54 | 28.10 ± 3.53 | 29.38 ± 4.81 | T = 3.626* | |

| Education | Bachelor | 63 | 59 | 122 | χ2 = 0.180, p = 0.671 |

| Master | 27 | 29 | 56 | ||

| School year | 1st | 27 | 24 | 51 | χ2 = 5.456, p = 0.141 |

| 2nd | 27 | 17 | 44 | ||

| 3rd | 18 | 30 | 48 | ||

| 4th | 18 | 17 | 35 |

p < 0.001.

Table 2.

TCI and MBI-SS subscales in male and female participants.

| Male | Female | Totals | t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCI | NS | 33.26 ± 9.70 | 33.56 ± 10.58 | 33.40 ± 10.12 | −0.198 |

| HA | 37.07 ± 10.66 | 39.17 ± 12.49 | 38.11 ± 11.62 | −1.210 | |

| RD | 45.13 ± 8.55 | 47.87 ± 9.56 | 46.44 ± 9.13 | −1.951 | |

| PS | 47.06 ± 9.54 | 47.31 ± 9.31 | 47.18 ± 9.40 | −0.178 | |

| SD | 51.09 ± 10.10 | 51.44 ± 9.88 | 51.26 ± 10.43 | −0.226 | |

| CO | 57.82 ± 8.49 | 58.93 ± 8.51 | 58.37 ± 9.00 | −0.822 | |

| ST* | 28.19 ± 12.07 | 32.31 ± 11.79 | 30.22 ± 12.07 | −2.302* | |

| MBI-SS | Exhaustion | 20.36 ± 7.79 | 22.51 ± 8.07 | 21.42 ± 7.98 | −1.813 |

| Cynicism | 13.92 ± 6.13 | 14.55 ± 6.28 | 14.23 ± 6.19 | −0.670 | |

| Inefficiency | 21.33 ± 6.52 | 21.57 ± 5.28 | 21.45 ± 5.93 | −0.264 | |

| Total burnout | 55.61 ± 16.28 | 57.63 ± 15.78 | 57.10 ± 16.06 | −1.254 | |

CO, cooperativeness; HA, harm avoidance; MBI-SS, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey; NS, novelty-seeking; PS, persistence; RD, reward-dependence; SD, self-directedness; ST, self-transcendence; TCI, Temperament and Character Inventory.

p < 0.05.

The correlation coefficients between subscales of TCI and MBI-SS are presented in Table 3. Three of four burnout scales (e.g., exhaustion, cynicism, inefficacy, and total burnout scales) except for cynicism showed positive correlations with the scores of HA. All four burnout scales showed negative correlations with the scores of SD. RD and PS were negatively correlated with inefficacy scale and CO was negatively correlated with cynicism and total burnout scales. NS and ST did not show significant correlation with all MBI-SS subscales.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients between TCI and MBI-SS subscales.

| TCI |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS | HA | RD | PS | SD | CO | ST | ||

| MBI-SS | Exhaustion | 0.012 | 0.269*** | −0.007 | −0.021 | −0.267*** | −0.122 | 0.135 |

| Cynicism | 0.145 | 0.120 | −0.086 | −0.067 | −0.150* | −0.177* | 0.060 | |

| Inefficacy | 0.050 | 0.181* | −0.171* | −0.169* | −0.284*** | −0.109 | −0.041 | |

| Total burnout | 0.080 | 0.247* | 0.185 | −0.099 | −0.296*** | −0.169* | 0.075 | |

CO, cooperativeness; HA, harm avoidance; MBI-SS, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey; NS, novelty-seeking; PS, persistence; RD, reward-dependence; SD, self-directedness; ST, self-transcendence; TCI, Temperament and Character Inventory.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

To further analyze the effects of personality traits on academic burnout, stepwise regression analyses were performed. Demographic variables including sex and school year were introduced in Model 1 (Step 1), and all seven personality variables of TCI were added in Model 2 (Step 2). Table 4 reported here was the full model after sex, school year, and all seven personality traits of TCI were included.

Table 4.

Stepwise regression analysis on the academic burnout subscales of exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy.

| 95% CI for unstandardized coefficient |

Standardized coefficient | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | β | |||

| Exhaustion | HA | 0.134 | 0.234 | 0.269 | 3.699** |

| F(1, 176) = 13.679, p < 0.001, adj R2 = 0.067 | |||||

| Cynicism | CO | −0.176 | −0.074 | −0.182 | −2.470* |

| NS | 0.047 | 0.137 | 0.150 | 2.035* | |

| F(1, 175) = 4.983, p < 0.01, adj R2 = 0.043 | |||||

| Inefficacy | SD | −0.202 | −0.120 | −0.284 | −3.924** |

| F(1, 176) = 15.396, p < 0.001, adj R2 = 0.075 | |||||

| Total burnout | SD | −0.566 | −0.344 | −0.296 | −4.104** |

| F(1, 176) = 16.846, p < 0.001, adj R2 = 0.082 | |||||

Age and sex were added to the model as a first step (Model 1), and seven personality dimensions of character and temperament were introduced as second step (Model 2). Since the age and sex introduced in earlier model were not significant, the final model can be considered as the full model.

CI, confidence interval; CO, cooperativeness; HA, harm avoidance; NS, novelty-seeking; SD, self-directedness.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

We found that sex and school year did not explain any burnout scales. Inefficacy and burnout total scales were negatively associated with SD; that is, those who are more purposeful and responsible feel more efficient and have less burnout. Emotional exhaustion scale was positively associated with HA; that is, those who are more fearful and shy feel easily exhausted in emotion. With respect to the cynicism, CO and NS showed negative and positive association with it, respectively; that means less empathic and more impulsive people tend to express a cynical attitude.

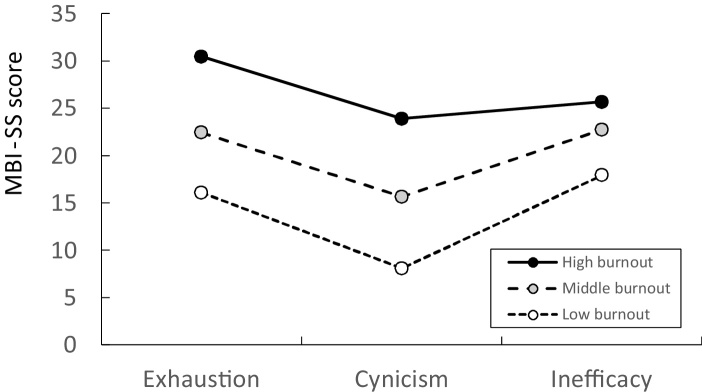

The LPA identified three latent academic burnout subgroups as the best solution (Table 5), and three BMI-SS subscale scores of high, middle, and low latent burnout subgroups are presented in Fig. 1. The three-latent subgroup model (3-class solution) fits the data significantly better than the two-class solution and not worse than the four-class solution considering the smaller BIC and adjusted BIC, the smaller p value of VLMR and LMR, and the greater entropy.

Table 5.

Fit indices for latent profile analysis of participants’ burnout subscales

| BIC | Adj. BIC | VLMR p | LMR p | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Class solution | 3494.112 | 3462.443 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.706 |

| 3-Class solution | 3474.667 | 3430.331 | 0.0063 | 0.0077 | 0.801 |

| 4-Class solution | 3484.710 | 3427.706 | 0.0440 | 0.0494 | 0.835 |

| 5-Class solution | 3494.555 | 3424.883 | 0.2354 | 0.2491 | 0.792 |

| 6-Class solution | 3505.983 | 3423.644 | 0.4943 | 0.4990 | 0.823 |

Adj. BIC, Adjusted Baysian Information Criterion; VLMR p, Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Difference Test p value; LMR, Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Difference Test p value.

Fig. 1.

Latent academic burnout subgroups based on three burnout subscales of MBI-SS of the participants.

Low burnout subgroup was presented as grey triangle, middle burnout subgroup as orange rectangle and high burnout subgroup as blue circle.

MBI-SS, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey.

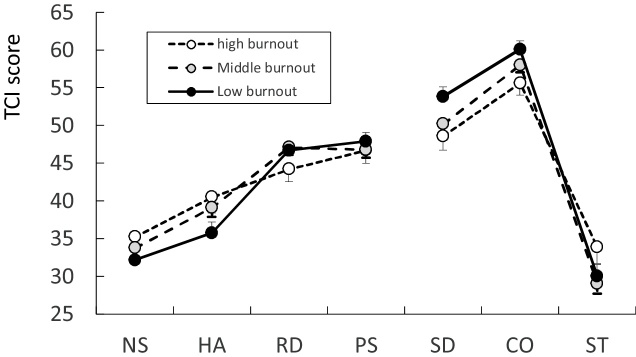

The significant differences of personality traits among three latent burnout subgroups were analyzed with profile analysis (Fig. 2), and there were significant differences between three latent academic burnout groups. The TCI seven personality profile of the three latent burnout subgroups was not flat (Greenhouse-Geisser correction, df = 4.158, F = 139.768, p < 0.001) and the interaction of the three groups was significantly different as for the parallelism (Greenhouse-Geisser correction, df = 8.316, F = 2.307, p = 0.018).

Fig. 2.

TCI profile of three latent burnout subgroups.

Data shown as mean and standard errors.

CO, cooperativeness; HA, harm avoidance; NS, novelty-seeking; PS, persistence; RD, reward-dependence; SD, self-directedness; ST, self-transcendence; TCI, Temperament and Character Inventory.

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the effects of personality traits on academic burnout in Korean medical students. For this purpose, we measured the Cloninger’s TCI to assess temperament and character aspects at the beginning of the semester and the BMI-SS for burnout symptoms at the end of the semester. HA and NS of the temperament domain were found to be susceptibility factors, and SD and CO of the character domain acted as protective factors for academic burnout. In addition, three latent burnout subgroups were identified and the personality profiles of the three latent burnout subgroups were significantly different.

Levels of NS and HA temperament were found to be lower and those of SD and CO were higher than the cohort population in Korea. In addition, the differences of ST between male and female (Table 2) is common in Eastern countries.33 These personality characteristics of Korean medical school students suggest that they are independent and reliable hard workers with empathic and kind minds. However, this study also disclosed that even students with healthy personality characteristics could be inclined toward burnout syndromes when they are exposed to the challenging and competitive medical school for a long period of time, particularly with higher NS and HA in temperament and lower SD and CO in character dimension (Table 4 and Fig. 2).

Therefore, there is a need for screening temperament and character dimensions when the students are enrolled in medical school, and providing person-centered prevention programs for improving self-awareness and reflectiveness and helping communication skills with colleagues. These would achieve a more mature and healthy medical school environment which is resilient to academic stress and maintaining high academic efficacy.

It was identified that lower scores of SD and CO and higher scores of HA and NS were correlated with greater academic burnout of students regardless of sex and age. Regarding subscales of MBI-SS, inefficacy was predicted by lower SD, and higher exhaustion was associated with higher HA. In addition, cynicism was characterized by the combination of higher NS and lower CO. These findings regarding total burnout are consistent with previous studies,24, 25 that lower SD and CO and higher HA scores are related with personality disorders and other mental disorders.41, 42, 43, 44

People with high HA would often display pessimism, be easily fatigued and fearful or anxious, causing emotional and physical exhaustion. In addition, students with low CO would demonstrate a hostile, biased, and opportunistic attitude to others and it is difficult for them to engage with others in medical school.45 It is difficult for those with low SD to do their best for a long term goal and show a self-accepting and ordered attitude, ending in inefficacy at medical school. Taking all these together, those with personality traits of low SD and CO and/or high HA would face uncertainty and much stress in everyday life of medical school, and would easily succumb to chronic stressful situations and become exhausted physically and emotionally, resulting in academic burnout at medical school.45

As for the subscales of academic burnout, cynicism was predicted by the combination of low CO and high NS. People with high NS were described as exploratory, excitable, impulsive, and irritable, and could not tolerate the routine and simple work. In the highly competitive and strict environment of medical school, students should demonstrate reflective, stoic, reserved traits to achieve good grades which are the opposite traits to those of high NS. In addition, those with low CO like to criticize others and act alone rather than to empathize and work together. Combined with high NS traits, lower cooperative people might keep a distance from others’ troubles and be less cooperative, resulting in a cynical attitude.

On the contrary to our results of CO, research using Japanese residents in medicine showed that those with higher CO are vulnerable to academic burnouts,46 which is inconsistent to the majority of previous researches. There might be various ways to interpret these results and one of them could be a different perspective from the collectivistic versus individual society. In a highly collectivistic society such as Japan, emphasizing the cooperative attitude toward others by social learning and being highly cooperative means that they are very sensitive to others’ difficulties and could not ignore them, which leads to helping others despite having their own work. This finding should be explored thoroughly in future studies whether the sociocultural differences modulate the effects of CO, and the CO is the protective or aggravating factor for academic burnouts in Western and Eastern countries.

The limitations of the present study are as follows. First, the individuals in this study include a small number of Korean medical students and this might prevent the generalization of the present findings. Since the level of CO might have different modulating effects depending on the culture, further studies should be followed using different cultural backgrounds and larger sample sizes in order to illuminate the universal traits. Second, the present study only focused on personality factors of temperament and character as causes of academic burnouts. Other variables affecting academic burnouts should be explored to understand the causal relationships such as emotional and psychological status.

The present study is the first article to examine the effects of temperament and character traits on academic burnout using regression analysis and LPA with a Korean sample of medical students. Personality traits such as high HA of temperament and low SD of character play important roles in academic burnouts. Interventions focusing on vulnerable temperament and character development should be considered for the well-being of the medical students to prevent academic burnouts.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

References

- 1.Bjorksten O., Sutherland S., Miller C., Stewart T. Identification of medical student problems and comparison with those of other students. J Med Educ. 1983;58:759–767. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye L.N., Thomas M.R., Massie F.S., Power D.V., Eacker A., Harper W. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guthrie E., Campbell M., Black D., Creed F., Bagalkote H., Shaw C. Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: a five-year prospective longitudinal study. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:237–243. doi: 10.1177/014107689809100502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guthrie E., Black D., Shaw C., Hamilton J., Creed F., Tomenson B. Embarking upon a medical career: psychological morbidity in first year medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29:337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi M., Cho Y. The effects of life stress, perceived anxiety control, and coping style on anxiety symptoms in college students. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2005;24:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh M.S., Jeon H.J., Lee H.W., Lee H.J., Han S.K., Hahm B.J. Depressive disorders among the college students: prevalence, risk factors, suicidal behaviors and dysfunctions. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2006;45:432–437. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlin M.E., Runeson B. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among medical students entering clinical training: a three year prospective questionnaire and interview-based study. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An H., Chung S., Park J., Kim S.-Y., Kim K.M., Kim K.-S. Novelty-seeking and avoidant coping strategies are associated with academic stress in Korean medical students. Psychiatr Res. 2012;200:464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaufeli W.B., Martinez I.M., Pinto A.M., Salanova M., Bakker A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students a cross-national study. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2002;33:464–481. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jennett H.K., Harris S.L., Mesibov G.B. Commitment to philosophy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:583–593. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005996.19417.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freudenberger H.J. Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues. 1974;30:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherniss C. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1980. Staff burnout: Job stress in the human services. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freudenberger H.J., Richelson G. Bantam; Garden City, NY: 1981. Burn-out: The high cost of high achievement. What it is and how to survive it. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farber B.A. Spencer Foundation; Chicago, IL: 1982. Teacher burnout: Assumptions, myths, and issues. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maslach C., Jackson S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs S.R., Dodd D. Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. J Coll Stud Dev. 2003;44:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eastburg M.C., Williamson M., Gorsuch R., Ridley C. Social support, personality, and burnout in nurses. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1994;24:1233–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills L.B., Huebner E.S. A prospective study of personality characteristics, occupational stressors, and burnout among school psychology practitioners. J School Psychol. 1998;36:103–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakker A.B., Van Der Zee K.I., Lewig K.A., Dollard M.F. The relationship between the big five personality factors and burnout: A study among volunteer counselors. J Soc Psychol. 2006;146:31–50. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.146.1.31-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huebner E.S., Mills L.B. Burnout in school psychology: The contribution of personality characteristics and role expectation. Spec Serv Sch. 1994;8:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zellars K.L., Perrewe P.L., Hochwarter W.A. Burnout in health care: The role of the five factors of personality. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:1570–1598. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cloninger C.R., Svrakic D.M., Przybeck T.R. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang N., Sato T., Hara T., Takedomi Y., Ozaki I., Yamada S. Correlations between trait anxiety, personality and fatigue: study based on the Temperament and Character Inventory. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazici A.B., Esen O., Yazici E., Esen H., Ince M. The relationship between temperament and character traits and burnout among nurses. J Psychol Psychother. 2014;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pejušković B., Lečić-Toševski D., Priebe S., Tošković O. Burnout syndrome among physicians–the role of personality dimensions and coping strategies. Psychiatria Danubina. 2011;23:389–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melchers M.C., Plieger T., Meermann R., Reuter M. Differentiating burnout from depression: personality matters! Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raycheva R.D., Asenova R.S., Kazakov D.N., Yordanov S.Y., Tarnovska T., Stoyanov D.S. The vulnerability to burn out in healthcare personnel according to the Stoyanov-Cloninger model: evidence from a pilot study. Int J Pers Cent Med. 2012;2:552–563. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoyanov D.S., Cloninger C.R. Relation of people-centered public health and person-centered healthcare management: a case study to reduce burn-out. Int J Pers Cent Med. 2012;2:90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cloninger C.R., Svrakic D.M. Integrative psychobiological approach to psychiatric assessment and treatment. Psychiatry. 1997;60:120–141. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1997.11024793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mojsa-Kaja J., Golonka K., Marek T. Job burnout and engagement among teachers-Worklife areas and personality traits as predictors of relationships with work. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2015;28:102–119. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eley D.S., Cloninger C.R., Walters L., Laurence C., Synnott R., Wilkinson D. The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing well being. Peer J. 2013;1:e216. doi: 10.7717/peerj.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cloninger C.R. On well-being: current research trends and future directions. Mens Sana Monogr. 2008;6:3–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.40564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S.H., Han S.Y., Kim J.D., Choi S.M., Lee S.J., Jung H.L. Study on stress and burnout in medical education at the school of Korean medicine. J Orient Neuropsychiatr. 2015;26:103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cloninger C.R. The psychobiological theory of temperament and character: comment on Farmer and Goldberg. Psychol Assess. 2008;2008(20):292–299. doi: 10.1037/a0012933. discussion 300–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chae H., Kim S.H., Han S.Y., Lee S.J., Kim B., Kwon Y. Study on the psychobiological characteristics of Sasang Typology based on the type-specific pathophysiological digestive symptom. Korean J Orient Physiol Pathol. 2014;28:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min B.B., Oh H.S., Lee J.Y. Maumsarang; Seoul, Korea: 2007. Temperament and Character Inventory-Family Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2005. Mplus Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanza S.T., Flaherty B.P., Collins L.M. Latent class and latent transition analysis. In: Schinka J., Velicer W.A., editors. Handbook of psychology: Research methods in psychology. Wiley; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 663–685. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nylund K.L., Asparouhov T., Muthen B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Structure Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D., editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fassino S., Abbate-Daga G., Amianto F., Leombruni P., Boggio S., Rovera G.G. Temperament and character profile of eating disorders: a controlled study with the Temperament and Character Inventory. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:412–425. doi: 10.1002/eat.10099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svrakic D.M., Draganic S., Hill K., Bayon C., Przybeck T., Cloninger C. Temperament, character, and personality disorders: etiologic, diagnostic, treatment issues. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:189–195. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cloninger C.R., Bayon C., Svrakic D.M. Measurement of temperament and character in mood disorders: a model of fundamental states as personality types. J Affect Disord. 1998;51:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cloninger C.R., Zohar A.H. Personality and the perception of health and happiness. J Affect Disord. 2011;128:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eley D.S., Leung J., Hong B.A., Cloninger K.M., Cloninger C.R. Identifying the dominant personality profiles in medical students: Implications for their well-being and resilience. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyoshi R., Matsuo H., Takeda R., Komatsu H., Abe H., Ishida Y. Burnout in Japanese residents and its associations with temperament and character. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;24:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]