Abstract

Background

The interpersonal model of loss of control (LOC) eating proposes that interpersonal problems lead to negative affect, which in turn contributes to the onset and/or persistence of LOC eating. Despite preliminary support, there are no data examining the construct validity of the interpersonal model of LOC eating using temporally sensitive reports of social stress, distinct negative affective states, and laboratory energy intake.

Method

117 healthy adolescent girls (BMI: 75th–97th %ile) were recruited for a prevention trial targeting excess weight gain in adolescent girls who reported LOC eating. Prior to the intervention, participants completed questionnaires of recent social stress and consumed lunch from a multi-item laboratory test meal. Immediately before the test meal, participants completed a questionnaire of five negative affective states (anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, anxiety). Bootstrapping mediation models were conducted to evaluate pre-meal negative affect states as explanatory mediators of the association between recent social stress and palatable (desserts and snack-type) food intake. All analyses adjusted for age, race, pubertal stage, height, fat mass percentage, and lean mass.

Results

Pre-meal state anxiety was a significant mediator for recent social stress and palatable food intake (ps < .05). By contrast, pre-meal state anger, confusion, depression, and fatigue did not mediate the relationship between social stress and palatable food intake (ps > .05).

Discussion

Pre-meal anxiety appears to be the salient mood state for the interpersonal model among adolescent girls with LOC eating. Interventions that focus on improving both social functioning and anxiety may prove most effective at preventing and/or ameliorating disordered eating and obesity in these adolescents.

Keywords: interpersonal model, loss of control eating, laboratory test meal, negative affect, social stress, anxiety

1. Introduction

Loss of control (LOC) eating, or the subjective experience of being unable to stop eating, regardless of the amount of food consumed, is commonly reported by youth [1]. The endorsement of recent LOC eating is associated with greater depressive and anxiety symptoms [2–4], lower self-esteem [5, 6], higher likelihood of overweight and obesity [7], more physiological markers of stress [8, 9], and a greater odds of presenting with components of the metabolic syndrome [10]. Of particular concern are data demonstrating that LOC eating places youth at undue risk for excess weight and fat gain [11, 12] and exacerbation of metabolic syndrome components [13]. This may be partially be due to the consistent finding that youth with LOC eating tend to consume meals comprised of highly palatable dessert and snack-type foods compared to their peers without LOC eating [14–16]. Moreover, reports of LOC eating in adolescence and emerging adulthood appear to increase risk for future psychosocial impairment, depression [7, 17], the development of partial- and full-syndrome binge eating disorder, and the worsening of mood symptoms [18].

One theoretical framework for understanding LOC eating is interpersonal theory [19]. Originally stemming from the adult depression literature [20], the interpersonal model of LOC eating highlights the importance of negative affect for both the development and maintenance of aberrant eating [19]. Specifically, the interpersonal model proposes that difficulties characterized by high or poorly resolved conflict and/or inadequate support in relationships lead to negative emotions. In turn, negative emotions contribute to the onset and/or persistence of LOC eating as a mechanism to cope with interpersonal distress [21–23]. Thus, interpersonal theory is an extension of affect theory, which proposes that out of control eating provides relief from negative affective states either through escape or by means of a “trade off” between an aversive emotion that precipitates the LOC eating episode (e.g., anger, frustration, anxiety) and a less aversive emotion following the episode [e.g., guilt; 24]. While eating provides initial relief from the negative affective state and thus is reinforcing, relief is often temporary [25]. As a result, in some individuals, eating develops into a maladaptive strategy for managing negative affect, as repeated LOC eating episodes become needed to sustain relief [26].

A number of studies have supported components of the affect theory of LOC eating [26–30]. For example, in a cohort of adolescent girls who reported LOC eating, we found that a composite score of several negative affective states (anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, and anxiety) was positively linked to highly palatable snack food intake as measured by meal intake at a laboratory test meal. Examining palatable food intake as a proxy for LOC eating [14, 15] provided a more objective measure of out of control eating than self-report [26]. Yet, we did not evaluate the individual components of negative affect or the role of interpersonal factors in this report. Elucidating specific facets of negative affect and interpersonal factors would allow for more targeted, and thus potentially more effective, interventions in these youth. Extending these data to test the full interpersonal model may be particularly important for understanding LOC eating in adolescence. During this developmental stage, relationships are closely tied to self-evaluation and are often a primary source of social stress [31]. In part because of the association with having excess weight, youth with LOC eating are particularly vulnerable to forms of social stress such as weight-related teasing and social isolation [17]. Not surprisingly, these factors have been suggested to influence the onset and course of LOC eating [32–36]. Indeed, results from longitudinal studies indicate that family weight-based teasing [37, 38] and impaired interpersonal functioning [39] predicts increases in and the onset of future disordered eating behaviors. Similarly, among females, greater psychosocial problems in late adolescence increase the odds of having binge eating in early adulthood, thus highlighting interpersonal problems as a putative risk factor for binge eating later on in life [36].

While the interpersonal model has been widely used to explain binge eating in adults [e.g., 28, 29, 40–43], and interpersonal psychotherapy has been adapted as an efficacious treatment for adult binge eating disorder [19, 44], only two studies have simultaneously evaluated all components of the interpersonal model of LOC eating in youth [27, 30]. The first study used structural equation modeling in a large sample of children and adolescents and found that parent-reported social problems were positively associated with children’s reported presence of LOC eating. This relationship was mediated by children’s reports of trait-like negative affect [30]. However, this study had several limitations. There was no objective measurement of food intake, and by having all measures collected at one time point, the temporal sequence of constructs remains unclear [45]. The second study used ecological momentary assessment in adolescent girls with overweight and found that although interpersonal problems predicted LOC eating episodes, and between-subjects interpersonal problems predicted increased negative affect, negative affect did not predict LOC eating episodes [27]. However, this study was not adequately powered for mediation and also did not examine specific components of interpersonal problems or negative affect [27].

Therefore, to extend on our prior work [26, 30], the objective of this study was to examine the validity of the interpersonal model of LOC eating using temporally sensitive reports of interpersonal stress, distinct negative mood states, and snack food intake as a proxy for LOC eating [14, 15]. We hypothesized that among adolescent girls with reported LOC eating, recent social stress would be associated with highly palatable dessert and snack food intake in the laboratory [26]. Moreover, we explored several negative affective states to determine the specific moods that mediate the relationship between social stress and intake.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Participants were adolescent girls (12–17 y) recruited for a prevention trial aimed at reducing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at high-risk for adult obesity (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00263536). Some of these data have been previously published [26, 46, 47], and this paper is an extension of previously published research [26].

To be eligible for the study, girls were deemed at risk for excess weight gain due to a body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) between the 75th and 97th percentiles and the report of at least one episode of LOC eating in the month prior to assessment. Participants were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers, referrals from physicians’ offices, mailings to local area parents, flyers distributed through local middle and high school parent listservs, postings at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Maryland, and local public facilities, with permission. Girls were excluded if they had a major medical or psychiatric condition (other than binge eating disorder), were currently taking medication known to impact eating behavior and/or weight, or had a recent significant weight loss for any reason (exceeding 3% of body weight). The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at USUHS and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

2.2. Procedure and Measures

Informed parental/guardian consent and child assent were obtained for all participants. At baseline, prior to participation in the prevention program, girls completed two screening visits. At the first visit, participants completed body measurements, psychological interviews, and self-report questionnaires about recent social stress. At a second visit (within 1–2 weeks of the first screening appointment), girls completed a questionnaire assessing state negative affect and then immediately following consumed lunch from a laboratory test meal designed to model a LOC eating episode [15, 48].

2.2.1. Body measurements

Height (cm) was measured in triplicate by stadiometer and fasting weight (kg) was measured by calibrated scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using height, averaged across the three measurements, and weight. We then calculated age- and sex-adjusted BMI-z, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth standards [49]. Body lean mass (kg) and body fat mass (%) were measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). DXA measurements were taken using a calibrated Hologic QDR-4500A instrument (Bedford, MA). Pubertal staging [50] was based on physical examination by an endocrinologist or nurse practitioner. Breast development was assessed by inspection and palpation and assigned according to the five stages of Tanner [51]. If stage was discordant between right and left breasts, the higher Tanner stage was assigned. Tanner stage categories were then combined into pre-puberty (Tanner Stage 1), early/mid-puberty (Tanner Stages 2 and 3), and late puberty (Tanner Stages 4 and 5).

2.2.2. LOC eating

Participants were administered the Eating Disorder Examination version 12.0 [52] to determine the presence of at least one episode of LOC eating in the past 28 days. The Eating Disorder Examination has demonstrated good inter-rater reliability and discriminant validity in pediatric samples [53, 54] and excellent reliability in the present sample [55].

2.2.3. Social adjustment

The Social Adjustment Scale [56] is a questionnaire assessing social functioning in four domains: school, friends, family, and dating. The Social Adjustment Scale has shown excellent reliability and validity [57] and has been successfully adapted for adolescents [58, 59]. Consistent with prior studies [55, 60], only the friends, family, and school subscales of the Social Adjustment Scale were included. The Social Adjustment Scale demonstrated good reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .86).

2.2.4. Loneliness and social dissatisfaction

The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale [61], a self-report questionnaire, was used to assess the participant’s loneliness and social dissatisfaction with social relationships. The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale asks participants to rate 24 items (e.g., “I don’t get along with other children,” “I can find a friend when I need one”) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “always true” to “not at all true,” with higher scores on the total score indicating greater loneliness and social dissatisfaction. The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale has shown acceptable internal consistency and reliability [61, 62]. The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale also demonstrated excellent reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s α = .90).

2.2.5. Pre-meal state negative affect

Immediately before the test meal, participants completed the Brunel Mood Scale [63]. The Brunel Mood Scale assesses present mood by asking participants to rate how they currently feel for 24 mood descriptors on a 5-point Likert scale, with 0 representing “not at all” and 4 representing “extremely”. The Brunel Mood Scale generates six subscales: anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, anxiety/tension, and vigor [15, 63, 64]. All scales, other than vigor, capture negative affective states [63, 65].

2.2.6. Observed intake during laboratory test meal modeled to capture a LOC eating episode

Following an overnight fast beginning at 10:00pm the night before, at approximately 11:00am, participants were presented with a buffet test meal (9,835 kcal; 12% protein, 51% carbohydrate, 37% fat) containing a broad array of foods that varied in macronutrient composition [15, 26, 48]. Girls were played a tape-recorded instruction to “let yourself go and eat as much as you want,” and then were left alone in a private room to consume the meal. The energy content and macronutrient composition for each item were determined using data from nutrient information supplied by food manufacturers as well as the U.S. Department of Agriculture Nutrient Database for Standard Reference [66]. Individual foods were weighed on electronic balance scales (in grams) before and after the meal, and both total intake and snack-type food intake were calculated for each participant. As described in previous studies [15, 26], snack-type food intake included both sweet snacks (e.g., jellybeans, chocolate candy) and salty snacks (e.g., pretzels, tortilla chips). Previous research has shown that LOC eating status moderates the relationship between test meal instruction and total food intake in girls with overweight, such that the combination of a “binge meal” instruction (versus an instruction to eat normally) and the presence of LOC eating leads to the greatest overall intake [15]. As reported previously [26], the majority (54.5%) of participants reported that the laboratory eating episode was slightly, moderately, very much or extremely similar to a typical LOC eating episode.

2.3. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 23.0. Data were screened for outliers and normality. Four extreme outliers were identified: one for snack-type calories consumed and three for total pre-meal Brunel Mood Scale score. Outliers were recoded to the respective next highest value for each variable [67]. Pre-meal Brunel Mood Scale anger, confusion, and depression subscales were log-transformed to achieve normality. Given the significant overlap in the constructs measured by the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale and Social Adjustment Scale, a composite score for recent social stress was created by averaging these two standardized scores (Cronbach’s α = .88).

To identify which individual pre-meal negative affective states mediated the relationship between social stress and palatable food intake in the laboratory, five mediation models were conducted using the Preacher and Hayes Indirect Mediation macro for SPSS [68]. Each model examined one of the Brunel Mood Scale negative affect subscales (i.e., anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, and anxiety) as the mediator, the composite social stress score as the independent variable, and snack-type food intake as the dependent variable. Exploratory analyses were also conducted to examine mediation analyses for total caloric intake.

To understand if the model was relevant for all facets of interpersonal stress, for significant negative affect subscales, four follow-up exploratory mediation analyses were conducted to examine separately the components of the composite score as independent variables: Social Adjustment Scale friends, family and school subscales and the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale. For all mediation models, bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples was used to estimate the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) for indirect effects. All mediation analyses adjusted for age, race (coded as non-Hispanic White or other), pubertal stage, height (cm), fat mass (%), and lean mass (kg). No statistical test assumptions were violated. All tests were two-tailed. Differences and similarities were considered significant when p-values were ≤ .05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Data from 117 adolescent girls aged 12–17 years (M = 14.47, SD = 1.65 years) were analyzed. Participants had an average BMI-z of 1.54 (SD = 0.34). Sixty-three (53.8%) participants identified as Non-Hispanic White, 31 (26.5%) as Non-Hispanic Black, 10 (8.5%) as Hispanic, and 13 (11.1%) as multiple races or another racial/ethnic group. On average, participants reported 4.65 (SD = 6.04) LOC eating episodes in the past 28 days. Based on the number of LOC eating episodes that were objective binge episodes in the past 3 months, one participant met DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder [69]. The pattern of findings did not differ with and without this participant; therefore, her data were included. Participant demographics, questionnaire data, and food intake data are shown in Table A.

Table A.

Participant Characteristics

| Age in years, M (SD) | 14.47 (1.65), range: 12.01–17.76 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 63 (53.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 31 (26.5) |

| Hispanic | 10 (8.5) |

| Other/Unknown | 13 (11.1) |

| BMI-z score, M (SD) | 1.54 (0.34), range: 0.68–2.06 |

| Lean Mass (kg), M (SD) | 44.09 (5.76), range: 29.95–57.65 |

| Fat Mass (%), M (SD) | 36.37 (5.24), range: 22.40–47.70 |

| Height (cm), M (SD) | 162.92 (8.00), range: 142.83–182.87 |

| Pubertal Stage*, n (%) | |

| Pre-Puberty | 3 (2.6) |

| Early/Mid-Puberty | 18 (15.4) |

| Late Puberty | 96 (82.1) |

| LOC Eating Episodes in past 28 days, M (SD) | 4.65 (6.04), range: 1–39 |

| Social Adjustment Scale | |

| Family, M (SD) | 1.89 (0.64), range: 1.00–4.00 |

| Friends, M (SD) | 1.96 (0.51), range: 1.10–3.40 |

| School, M (SD) | 3.45 (2.78), range: 1.00–8.00 |

| Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale, M (SD) | 29.16 (9.10), range: 16–58 |

| Brunel Mood Scale | |

| Anger, M (SD) | 0.53 (1.44), range: 0–9 |

| Confusion, M (SD) | 0.97 (1.63), range: 0–7 |

| Depression, M (SD) | 0.50 (1.16), range: 0–7 |

| Fatigue, M (SD) | 5.83 (4.03), range: 0–16 |

| Anxiety, M (SD) | 1.30 (1.81), range: 0–9 |

| Snack-type food intake (kcal), M (SD) | 295.15 (196.67), range: 0.00–873.02 |

| Total food intake (kcal), M (SD) | 1172.75 (437.95), range: 199.57–1172.75 |

Note: N = 117; LOC, loss of control;

Pubertal stage defined as: pre-puberty (Tanner Stage 1), early/mid puberty (Tanner Stages 2 and 3), and late puberty (Tanner Stages 4 and 5).

3.2. Mediation Model

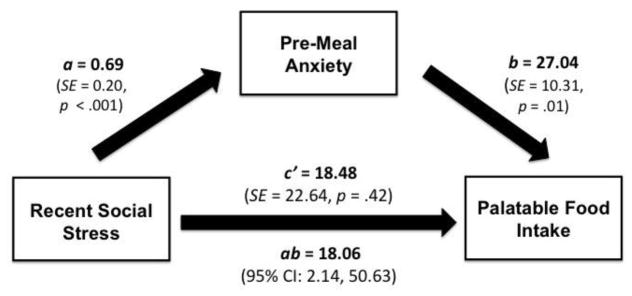

The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale was a significant mediator of the relationship between the composite recent social stress score and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.14; ab = 18.06, 95% bootstrap CI: [2.14, 50.63]; Figure A). Recent social stress was significantly associated with Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (a = 0.69, SE = .20, p < .001) and, in turn, Brunel Mood Scale anxiety was significantly associated with intake of snack-type food (b = 27.04, SE = 10.31, p = .01). The direct effect of recent social stress on intake of snack-type food (c = 37.23, SE = 22.06, p = .09) was decreased with the addition of Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (c’ = 18.48, SE = 22.64, p = .42).

Figure A.

Mediation model examining the relationship between recent social stress, pre-meal anxiety, and palatable food intake. The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale was a significant mediator of the relationship between the composite recent social stress score and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.14; ab =18.06, 95% bootstrap CI: [2.14, 50.63]). Recent social stress was significantly associated with Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (a = 0.69, SE = .20, p < .001), and Brunel Mood Scale anxiety was significantly associated with intake of snack-type food (b = 27.04, SE = 10.31, p = .01). The effect of recent social stress on intake of snack-type food (c = 37.23, SE = 22.06, p = .09) was decreased with the addition of Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (c’ = 18.48, SE = 22.64, p = .42). Mediation analyses adjusted for age, race (coded as non-Hispanic White or other), pubertal stage, height (cm), fat mass (%), and lean mass (kg).

By contrast, the anger (R2 = 0.11; 95% bootstrap CI: [−2.39, 29.46]), confusion (R2 = 0.11; 95% bootstrap CI: [−0.32, 32.33]), depression (R2 = 0.09; 95% bootstrap CI: [−3.62, 21.47]), and fatigue (R2 = 0.10; 95% bootstrap CI: [−1.61, 22.07]) subscales did not significantly mediate the association between the composite recent social stress score and intake of snack-type food. In exploratory analyses, no mood state subscale significantly mediated the relationship between the composite recent social stress score and total caloric intake (ps > .05).

3.3. Follow-Up Exploratory Analyses for Anxiety and Palatable Food Intake

3.3.1. Social adjustment: Family subscale

The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale was a significant mediator of the relationship between Social Adjustment Scale family and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.14; 95% bootstrap CI: [1.61, 69.34]). The family subscale was associated with Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (a = 1.16, SE = .25, p < .001), and state anxiety, in turn, was associated with intake of snack-type food (b = 24.65, SE = 10.70, p = .02). The significant effect of the family subscale on intake of snack-type food (c = 63.10, SE = 28.01, p = .03) became non-significant with the addition of Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (c’ = 34.45, SE = 30.16, p = .26).

3.3.2. Social adjustment: Friends subscale

The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale was a significant mediator of the relationship between Social Adjustment Scale friends subscale and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.15; 95% bootstrap CI: [0.82, 80.69]). The friends subscale was positively associated with Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (a = 1.13, SE = 0.32, p = .001), and state anxiety was associated with greater snack-type food intake (b = 24.97, SE = 10.25, p = .02). The significant effect of the friends subscale on intake of snack-type food (c = 80.73, SE = 35.20, p = .02) became non-significant with the addition of Brunel Mood Scale anxiety (c’ = 52.60, SE = 36.31, p = .15).

3.3.3. Social adjustment: School subscale

The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale did not significantly mediate the relationship between Social Adjustment Scale school problems and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.15; 95% bootstrap CI: [-.06, 9.10].

3.3.4. Loneliness and social dissatisfaction

The Brunel Mood Scale anxiety subscale was a partial mediator of the relationship between the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale score and snack-type food intake (R2 = 0.16; 95% bootstrap CI: [0.06, 4.13]). The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction score was associated with greater state anxiety (a = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = .009), and state anxiety was associated with more intake of snack-type food (b = 24.75, SE = 9.94, p = .01). The significant effect of Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction score on intake of snack-type food (c = 5.27, SE = 1.99, p = .01) was attenuated by the addition of state anxiety, but remained significant (c’ = 4.04, SE = 2.00, p = .046).

4. Discussion

In this test of the interpersonal model of LOC eating using in-laboratory food intake, we found pre-meal anxiety significantly mediated the relationship between recent social stress and the consumption of palatable (i.e., snack-type) food intake. Other aspects of pre-meal negative affect (anger, confusion, depression, and fatigue) did not significantly mediate the relationship between recent social stress and intake.

Prior studies have shown that state negative affect is linked with subsequent LOC eating [25, 70–73] and palatable food intake [26, 74]. However, we found only pre-meal state anxiety, but not state, anger, confusion, depression or fatigue, explained the relationship between recent social stress and palatable food intake. Anxiety may be particularly important for the onset and maintenance of LOC eating. Not only are anxiety disorders commonly comorbid with binge eating disorder in adults [75], but LOC eating is associated with [3, 76], and predictive of anxiety symptoms in youth [18]. Moreover, neural data suggest that similar to youth with anxiety problems [77, 78], those with LOC eating are highly responsive to experimentally-induced exposure to social anxiety, both in terms of brain region activation and subsequent eating behavior [79]. In the results from the trial from which data for the current analysis was collected, we found that found that anxiety moderated outcome. Specifically, compared to a standard-of-care control group, girls with high anxiety who received interpersonal psychotherapy had the greatest improvements in BMI-z and adiposity [60]. Notably, these findings are consistent with other trials testing interpersonal psychotherapy in adolescents [e.g., 80, 81, 82] and may speak to the relevance of anxiety in the interpersonal model. Taken together, these findings suggest that anxiety may be a particularly important facet of negative affect in adolescent girls who are above-average weight and who experience LOC eating.

In follow-up analyses, we found that all components of recent social stress, other than social problems pertaining to school, supported the interpersonal model. This finding is not entirely surprising. Unlike the Social Adjustment Scale friends and family subscales and the Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Scale that all assess the quality of interpersonal relationships, the Social Adjustment Scale school subscale primarily captures academic functioning [56, 83], which may not be as directly relevant to interpersonal theory. The current data lend support to the interpersonal model, suggesting that interpersonal stressors uniquely contribute to the development and/or maintenance of LOC eating and excessive palatable food intake [19]. However, it is possible that other types of stressors (e.g., academic stress), impact the development and/or maintenance of LOC eating and excessive palatable food intake through mechanisms other than anxiety.

In concert with some [14–16, 26], but not all [48, 84] data, we found no relationship between negative affect and total intake in a laboratory test meal. Indeed, prior studies show that snack intake better distinguishes youth with LOC eating from youth without LOC eating than total intake [14, 15], and may account for the associations between LOC eating and metabolic syndrome components [10] and C-reactive protein, a measure of chronic inflammation [9]. Thus, impacting dessert and snack food intake, specifically, may be an important target of excess weight gain prevention. In other findings from this trial, dessert and snack food intake was reduced following interpersonal psychotherapy relative to health education among girls with LOC eating [46]. Taken together, the interpersonal model may be particularly applicable for the excessive consumption of palatable foods. Further data are needed to examine the various components of social functioning and negative affective states to better elucidate and refine the interpersonal model of LOC eating in youth.

Study strengths include the use of a relatively diverse sample of adolescents, an objective assessment of body composition, and a well-controlled laboratory test meal. While not allowing for the determination of causality, the sequenced assessments of recent social stress, negative affect, and laboratory test meal allowed us to examine the construct validity of the interpersonal model of LOC eating using temporally sensitive measures over time. Limitations of the study include potentially reduced ecological validity, due to the use of a laboratory test meal. Ecological momentary assessment studies may be especially sensitive in assessing the temporal relationships between social stress, anxiety, and food intake in the natural environment. It is also possible that the failure to find certain effects was due to sample characteristics, given that girls with significant psychopathology were excluded. Additionally, this study only examined the interpersonal model of LOC eating in adolescent girls; therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to males or to other age groups. Moreover, although there are no clinical cutoffs for the questionnaires used in the current study, girls were generally healthy. Future replication studies in mixed-sex samples, younger children, as well as clinical populations are required. Future research should also involve examining anxiety and palatable food intake by experimentally manipulating exposure to social stress to elucidate the causality of these constructs. Finally, alternative biological and psychological mediators of the relationship between social stress and highly palatable food intake may identify novel intervention targets.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the interpersonal model appears to be salient among adolescent girls with LOC eating. The presence of state anxiety in response to recent social stress may place adolescents with LOC eating at high risk for exacerbated disordered eating, mood disturbances, and obesity. Interventions that focus on improving both social functioning and anxiety may be most effective for ameliorating eating and weight problems in adolescents with LOC eating.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant 1R01DK080906 (to MT-K), the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences grant R072IC (to MT-K), and the Intramural Research Program, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, grant 1ZIAHD000641 (to JAY). The funding sources had no involvement in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts

Disclaimer: J. A. Yanovski and M. Kozlosky are Commissioned Officers in the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS). The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of USUHS, HJF, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the PHS.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Marcus MD, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Loss of control eating disorder in children age 12 years and younger: proposed research criteria. Eat Behav. 2008;9:360–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldschmidt AB, Jones M, Manwaring JL, Luce KH, Osborne MI, Cunning D, et al. The clinical significance of loss of control over eating in overweight adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:153–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goossens L, Braet C, Van Vlierberghe L, Mels S. Loss of control over eating in overweight youngsters: the role of anxiety, depression and emotional eating. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17:68–78. doi: 10.1002/erv.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwé V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:112–22. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldschmidt AB, Loth KA, MacLehose R, Pisetsky EM, Berge JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Overeating with and Without Loss of Control: Associations with Weight Status, Weight-Related Characteristics, and Psychosocial Health. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:1150–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.22465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:149–55. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ranzenhofer LM, Engel SG, Crosby RD, Haigney M, Anderson M, McCaffery JM, et al. Real-time assessment of heart rate variability and loss of control eating in adolescent girls: A pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:199–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.22464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shank LM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Kelly NR, Schvey NA, Marwitz SE, Mehari RD, et al. Pediatric Loss of Control Eating and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Concentrations. Child Obes. 2016 doi: 10.1089/chi.2016.0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radin RM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Kelly NR, Pickworth CK, Shank LM, et al. Metabolic characteristics of youth with loss of control eating. Eat Behav. 2015;19:86–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, Malspeis S, Rosner B, Rockett HR, et al. Relation Between Dieting and Weight Change Among Preadolescents and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Stern EA, Miller R, Sebring N, Dellavalle D, et al. Children's binge eating and development of metabolic syndrome. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:956–62. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theim KR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Salaita CG, Haynos AF, Mirch MC, Ranzenhofer LM, et al. Children's descriptions of the foods consumed during loss of control eating episodes. Eat Behav. 2007;8:258–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanofsky-Kraff M, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, Kozlosky M, Schvey NA, Shomaker LB, et al. Laboratory assessment of the food intake of children and adolescents with loss of control eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:738–45. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldschmidt AB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley D. A laboratory-based study of mood and binge eating behavior in overweight children. Eat Behav. 2011;12:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason TB, Heron KE. Do depressive symptoms explain associations between binge eating symptoms and later psychosocial adjustment in young adulthood? Eat Behav. 2016;23:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, Roza CA, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:108–18. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilfley D, Frank M, Welch R, Spurrell E, Rounsaville B. Adapting Interpersonal Psychotherapy to a Group Format (IPT-G) for Binge Eating Disorder: Toward A Model for Adapting Empirically Supported Treatments. Psychother Res. 1998;8:379–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klerman G, Weissman M, Rounsaville B, Chevron E. Interpersonal Psychotherapy of Depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley D, Young JF, Mufson L, Yanovski SZ, Glasofer DR, et al. Preventing Excessive Weight Gain in Adolescents: Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Binge Eating. Obesity. 2007;15:1345–55. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heatherton TF, Baumeiser RF. Binge eating as an excape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Welch R, Wilfley DE. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): causal pathways and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:400–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenardy J, Arnow B, Agras WS. The aversiveness of specific emotional states associated with binge-eating in obese subjects. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:839–44. doi: 10.3109/00048679609065053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein RI, Kenardy J, Wiseman CV, Dounchis JZ, Arnow BA, Wilfley DE. What's driving the binge in binge eating disorder?: A prospective examination of precursors and consequences. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranzenhofer LM, Hannallah L, Field SE, Shomaker LB, Stephens M, Sbrocco T, et al. Pre-meal affective state and laboratory test meal intake in adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Appetite. 2013;68:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranzenhofer LM, Engel SG, Crosby RD, Anderson M, Vannucci A, Cohen LA, et al. Using ecological momentary assessment to examine interpersonal and affective predictors of loss of control eating in adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:748–57. doi: 10.1002/eat.22333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambwani S, Roche MJ, Minnick AM, Pincus AL. Negative affect, interpersonal perception, and binge eating behavior: An experience sampling study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:715–26. doi: 10.1002/eat.22410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanova IV, Tasca GA, Hammond N, Balfour L, Ritchie K, Koszycki D, et al. Negative affect mediates the relationship between interpersonal problems and binge-eating disorder symptoms and psychopathology in a clinical sample: a test of the interpersonal model. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:133–8. doi: 10.1002/erv.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott CA, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Columbo KM, Wolkoff LE, Ranzenhofer LM, et al. An examination of the interpersonal model of loss of control eating in children and adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:424–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mufson L, Moreau D, Weissman M, Klerman G. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Loth KA, Le Grange D, Neumark-Sztainer D. Which Dieters Are at Risk for the Onset of Binge Eating? A Prospective Study of Adolescents and Young Adults. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilbert A, Brauhardt A. Childhood loss of control eating over five-year follow-up. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:758–61. doi: 10.1002/eat.22312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner HH, Haines J, Austin SB, Field AE. A prospective study of overeating, binge eating, and depressive symptoms among adolescent and young adult women. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:478–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: A 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 2002;21:131–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Zhang J, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Overeating and Binge Eating in Emerging Adulthood: 10-Year Stability and Risk Factors. Dev Psych. 2016;52:475–83. doi: 10.1037/dev0000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ. Weight teasing and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal findings from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens) Pediatrics. 2006;117:e209–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumark-Sztainer DR, Wall MM, Haines JI, Story MT, Sherwood NE, van den Berg PA. Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stice E, Gau JM, Rohde P, Shaw H. Risk Factors That Predict Future Onset of Each DSM-5 Eating Disorder: Predictive Specificity in High-Risk Adolescent Females. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016 doi: 10.1037/abn0000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ansell EB, Grilo CM, White MA. Examining the interpersonal model of binge eating and loss of control over eating in women. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:43–50. doi: 10.1002/eat.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo Coco G, Sutton R, Tasca GA, Salerno L, Oieni V, Compare A. Does the Interpersonal Model Generalize to Obesity Without Binge Eating? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/erv.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivanova IV, Tasca GA, Proulx G, Bissada H. Does the interpersonal model apply across eating disorder diagnostic groups? A structural equation modeling approach. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;63:80–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiger H, Gauvin L, Jabalpurwala S, Seguin JR, Stotland S. Hypersensitivity to social interactions in bulimic syndromes: relationship to binge eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:765–75. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill AB. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1965;58:295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Crosby RD, Vannucci A, Kozlosky M, Shomaker LB, Brady SM, et al. Effect of adapted interpersonal psychotherapy versus health education on mood and eating in the laboratory among adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2016 doi: 10.1002/eat.22496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vannucci A, Shomaker LB, Field SE, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, Kozlosky M, et al. History of weight control attempts among adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Health Psychol. 2014;33:419–23. doi: 10.1037/a0033184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mirch MC, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, Schollnberger M, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, et al. Effects of binge eating on satiation, satiety, and energy intake of overweight children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:732–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States. Methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2000;246:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanner JM. Growth and endocrinology of the adolescent. In: Garner L, editor. Endocrine and Genetic Diseases of Childhood. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1969. pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fairburn CC, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CC, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–60. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, Yanovski SZ, Theim KR, Mirch MC, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, et al. Targeted prevention of excess weight gain and eating disorders in high-risk adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1010–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1111–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770090101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gameroff MJ, Wickramaratne P, Weissman MM. Testing the Short and Screener versions of the Social Adjustment Scale-Self-report (SAS-SR) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:52–65. doi: 10.1002/mpr.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mufson L, Fairbanks J. Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents: A One-Year Naturalistic Follow-up Study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1145–55. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Olfson M, Wiessman MM. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:577–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, et al. Excess Weight Gain Prevention in Adolescents: Three-Year Outcome Following a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asher SR, Wheeler VA. Children's loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:500–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galanaki EP, Polychronopoulou SA, Babalis TK. Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Among Behaviourally At-Risk Children. Sch Psychol Int. 2008;29:214–29. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terry PC, Lane AM, Lane HJ, Keohane L. Development and validation of a mood measure for adolescents. J Sports Sci. 1999;17:861–72. doi: 10.1080/026404199365425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brandt R, Herrero D, Massetti T, Crocetta TB, Guarnieri R, de Mello Monteiro CB, et al. The Brunel Mood Scale Rating in Mental Health for Physically Active and Apparently Healthy Populations. Health. 2016;08:125–32. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vannucci A, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Ranzenhofer LM, Matheson BE, Cassidy OL, et al. Construct validity of the emotional eating scale adapted for children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:938–43. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.US Department of Agriculture ARS, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Warner RM. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Mediation Models for Longitudinal Data in Developmental Research. Res Hum Dev. 2009;6:144–64. [Google Scholar]

- 69.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fifth Edition (DSM-5) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, et al. Negative affect prior to and following overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:641–53. doi: 10.1002/eat.22401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Engel SG, Durkin N, Beach HM, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of eating episodes in obese adults. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:747–52. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heron KE, Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, Smyth JM. Eating behaviors and negative affect in college women's everyday lives. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:853–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.22292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Simonich H, Smyth J, Mitchell JE. Daily mood patterns and bulimic behaviors in the natural environment. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell SL, Haynos AF, Crow SJ, Fruzzetti AE. An experimental analysis of the affect regulation model of binge eating. Appetite. 2016;110:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM. DSM-IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:228–34. doi: 10.1002/eat.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Elliott C, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Ranzenhofer LM, et al. Salience of loss of control for pediatric binge episodes: does size really matter? Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:707–16. doi: 10.1002/eat.20767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McClure EB, Parrish JM, Nelson EE, Easter J, Thorne JF, Rilling JK, et al. Responses to conflict and cooperation in adolescents with anxiety and mood disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:567–77. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, Parrish JM, Adler A, Blair JR, et al. Abnormal Attention Modulation of Fear Circuit Function in Pediatric Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:97–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jarcho JM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Nelson EE, Engel SG, Vannucci A, Field SE, et al. Neural activation during anticipated peer evaluation and laboratory meal intake in overweight girls with and without loss of control eating. Neuroimage. 2015;108:343–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Impact of comorbid anxiety in an effectiveness study of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:904–12. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000222791.23927.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Young JF, Gallop R, Mufson L. Mother-child conflict and its moderating effects on depression outcomes in a preventive intervention for adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:696–704. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Jekal A, Turner JB. The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression: IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:260–7. doi: 10.1037/a0018935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asher SR, Wheeler VA. Children's Loneliness: A Comparison of Rejected and Neglected Peer Status. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:500–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hilbert A, Rief W, Tuschen-Caffier B, de Zwaan M, Czaja J. Loss of control eating and psychological maintenance in children: an ecological momentary assessment study. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]