Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pain catastrophizing is a maladaptive response to pain that amplifies chronic pain intensity and distress. Few studies have examined how pain catastrophizing relates to opioid prescription in outpatients with chronic pain.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective observational study of the relationships between opioid prescription, pain intensity, and pain catastrophizing in 1,794 adults (F=1129; 63%) presenting for new evaluation at a large tertiary care pain treatment center. Data were sourced primarily from an open-source, learning health system and pain registry, and secondarily from manual review of electronic medical records. A binary opioid prescription variable (“yes/no”) constituted the dependent variable; independent variables were age, sex, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety.

RESULTS

Most patients were prescribed at least one opioid medication (57%; n=1,020). A significant interaction and main effects of pain intensity and pain catastrophizing on opioid prescription were noted (p<0.04). Additive modeling revealed sex differences in the relationship between pain catastrophizing, pain intensity and opioid prescription, such that opioid prescription became more common at lower levels of pain catastrophizing for females than for males.

CONCLUSIONS

Results supported the conclusion that pain catastrophizing and sex moderate the relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription. While males and females had similar pain catastrophizing scores, historically ‘subthreshold’ levels of pain catastrophizing were significantly associated with opioid prescription only for females. Our findings suggest that pain intensity and catastrophizing contribute to different patterns of opioid prescription for male and female patients, highlighting a potential need for examination and intervention in future studies.

Keywords: pain catastrophizing, chronic pain, opioid, opioids, sex differences, CHOIR

1. Introduction

With up to 40% of the global population experiencing ongoing pain,1,2 there is a need to better understand the experience of pain and associated treatment patterns. Pain catastrophizing3,4 -- a cascade of negative thoughts and emotions in response to actual or anticipated pain – is a key factor in pain-related outcomes. In experimental and clinical settings, pain catastrophizing is associated with amplified pain processing,5,6 greater pain intensity7 and greater disability.7,8 Pain catastrophizing may explain up to twenty percent of the variance in chronic pain intensity,9 and thus may influence other pain treatments, including opioid medications.

Pain catastrophizing has been identified as a risk factor for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain generally10 and among those with a history of substance use disorder.11 Post-surgically, opioid use is commonly quantified either by dose or by time to opioid cessation.12,13 Perioperative studies have yielded mixed findings for pain catastrophizing, with some reporting a direct relationship with morphine dose delivered either by patient controlled analgesia devices14 or by hospital staff,15 while other studies reported no association16 or an inverse association.17 Findings from a recent longitudinal study of 145 musculoskeletal trauma surgery patients suggested that pain catastrophizing predicted delayed opioid cessation after surgery.18 Using multivariate analyses, the authors found that pain catastrophizing was the strongest predictor of post-surgical opioid use 1–2 months after surgery. After controlling for anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and disability, pain catastrophizing accounted for 23% of the unique variance in persistent post-surgical opioid use.

In the outpatient setting, catastrophizing has been associated with opioid craving19, long-term opioid use in veterans,20 and opioid misuse.21 Given the positive associations found between catastrophizing and the aforementioned opioid responses and behaviors, it would follow that a similar association might exist for catastrophizing and receipt of opioid prescription in a larger civilian chronic pain population. However, to our knowledge, this latter relationship is unexplored. Characterization of the relationship between catastrophizing and opioid prescription in a larger chronic pain sample could enhance understanding and potentially reveal a therapeutic target for reducing need and use of opioids in chronic pain outpatients.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to characterize the relationship between existing opioid prescription and pain catastrophizing in a large sample of patients presenting for new evaluation at a chronic pain clinic. It has been found that in individuals with chronic non-cancer pain, the presence of co-morbid mental health diagnoses, particularly mood disorders, predicts the likelihood of opioid prescription,21 the degree of opioid use,11 and the likelihood of aberrant opioid use (e.g., opioid abuse or dependence).22 Consequently, we sought to characterize the relationship between pain catastrophizing and opioid prescription independent of the influences of these and other factors, including age,11 sex,23 and pain intensity,16,24 known to be relevant to opioid use and pain catastrophizing, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression.22 We aimed solely to identify any relationships between our variables of interest, in turn, allowing for future investigations to further explore any clinically significant findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and setting

The current study utilized a retrospective, observational method to examine a large sample of adult patients with chronic pain. Patients were seeking treatment at a large, urban, tertiary academic pain treatment center located in the San Francisco Bay Area in the United States. Data were extracted for patients with initial pain clinic visits between January 2014 and April 2015. Study procedures, which involved exclusively retrospective review of clinical data and therefore did not require informed consent from patients, were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Stanford University in Stanford, CA, USA.

2.2. Participants

All new patients who sought treatment at a tertiary academic outpatient pain management center in the San Francisco Bay Area between the aforementioned dates were eligible to be in the study. However, only those who had completed Pain-CHOIR in its entirety, 1794 patients, were included in the study.

2.3. Data collection

Data were collected using the Pain Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (Pain-CHOIR)25,26 (http://snapl.stanford.edu/choir). Pain-CHOIR is a learning health system that allows for deep phenotyping of patients while also identifying their treatment needs and facilitating rapid delivery of specialized pain services. The patient reported outcomes component of Pain-CHOIR is an electronic patient survey. For simplicity, the survey alone will be referred to as Pain-CHOIR. Pain-CHOIR, administered to all patients in the Stanford Pain Management Center, serves as a key component of the new patient evaluation procedure. Five days prior to their scheduled new patient medical evaluation, all patients receive an email with instructions to follow a link to register with the Pain-CHOIR system and complete their new patient survey. Patients who do not complete their Pain-CHOIR survey prior to their visit or lack the technologies (computer/smartphone, internet, email address) needed to access the survey are asked to complete the surveys at clinic check-in using a tablet computer provided by the clinic.

Data for the following measures were extracted from the initial Pain-CHOIR survey: demographic variables (education, marital status, and race), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale,27 average pain intensity, and the depression and anxiety item banks of the National Institutes of Health Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.28 Other demographic variables, such as date of birth (used to calculate age) and sex, were extracted from Stanford Hospitals and Clinics electronic medical record system. Additionally, all patients had accessible electronic medical records with physician notes that allowed for manual retrospective chart review. Finally, all pain diagnostic information was attained by collecting the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) billing codes assigned to each patient at initial clinic visit. The codes were reviewed and categorized according to diagnoses relevant to the field.

2.3.1. Opioid Prescription

Patients self-reported all current opioid prescription data, either electronically via Pain-CHOIR or verbally to clinic staff during their medical visit. For patients who verbally provided opioid medication information (n=711, 40%), opioid data were extracted via retrospective chart review in a step-wise manner. Step 1 involved recording current opioid medications for the initial clinic visit from physician documentation (the clinical note) in the electronic medical record. If data were absent in step 1, step 2 was employed, in which opioid data were extracted from the electronic medical record medication list. Step 2 was employed for less than 10% of the manually extracted opioid prescription data. Data collection screened for codeine, duragesic, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, levorphanol, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, tramadol, and suboxone. Active opioid prescription was recorded as a binary variable with 0 = no opioid prescriptions and 1 = any opioid prescription.

Midway through the study period, an opioid survey was included into Pain-CHOIR containing the following item: “Are you currently taking any opioid medications (such as Vicodin, Oxycontin, Oxycodone, Morphine, MS-Contin, Codeine, Actiq, Duragesic, Dilaudid, Demoral, Methadone, Percocet, Opana, Nucynta, Stadol, Ultram)?” The addition of the opioid question rapidly identified patients with current opioid prescriptions, thereby greatly facilitating data catchment. Thus, for 1083 patients, opioid prescription data were electronically extracted directly from Pain-CHOIR.

2.3.2. Patient Reported Outcome Measures

PCS

Pain catastrophizing was measured with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS).27 The PCS asks respondents to rate how frequently they respond to pain in a manner consistent with each of the 13 statements presented (e.g., “It’s awful and I feel that it overwhelms me.”). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“always”). A total PCS score is computed by summing the 13 items (range = 0 to 52) with higher scores reflecting higher levels of catastrophizing. The PCS contains 3 subscales: rumination, magnification, and feelings of helplessness. The PCS has been shown to have good internal and cross-population psychometric consistency.27,29–31 The coefficient alpha for the total PCS is 0.87.27

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression and Anxiety

Within Pain-CHOIR, PROMIS is delivered as a computer-based survey that uses a computerized adaptive testing approach based on item response theory to allow for item-level responses, greater precision achieved through lowered standard error and a smaller set of questions32 that gauge a psychometric domain on a continuum33 with reduced sensitivity to population variability.34 The PROMIS Depression and Anxiety item banks have demonstrated validity and consistency.35 PROMIS instruments quantify level of symptoms, are normed on the US population, and are reported using t-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.28

Average pain intensity

Average pain intensity was measured using the numeric rating scale which operates on a 0 to 10 scale with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable.36 Respondents were asked to consider the previous 7 days for rating their average pain intensity. The numeric rating scale has been validated for specificity and use in chronic pain research.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In the statistical analysis of clinical trials and observational studies, valid characterizations of effects are contingent on the accurate selection of the statistical model. In the field of pain research, linear models are predominantly used. Linear models, including linear regression, logistic regression, and semi-parametric methods such as Cox proportional hazard modeling, assume that the effects of the covariates on the outcome variable are linear and equal across the entire range of observed values. In situations where the phenomenon under question is in fact non-linear, model mis-specification can lead to inaccurate estimates that can result in erroneous statistical inferences via outliers or dilution of true effects. Consequently, individual investigators may be misled into costly pursuits of inaccurate conclusions. Scientifically, neglecting non-linearity may lead to inconsistent statistical estimates and paradoxical bodies of literature. In some cases, non-linearity may be apparent visually during data analysis and accounted for by the incorporation of polynomial covariate terms. However, this is not always true, suggesting that this approach may not be sufficient for detecting and addressing potentially non-linear relationships. Models involving binary outcome variables may present particular difficulties in this regard.

To bypass normal distribution assumptions and account for non-linear relationships, we employed both generalized linear model and generalized additive model. General linear modeling is a flexible, linear statistical model that allows for the analysis of variables with non-normal distributions using a link function. General linear model building was performed using a logit link function for the binary outcome of “any opioids prescribed” with covariates (x) of pain intensity, anxiety, depression, pain catastrophizing, pain intensity*pain catastrophizing (interaction), age, and sex.

General additive modeling, a flexible non-linear model, was used to identify and characterize the effect of potential, nonlinear prognostic factors on the binary outcome of opioid prescription with smoothing spline curves to fully estimate nonlinear effects. Opioid prescription was analyzed as a possible prognostic factor in the association between pain intensity and pain catastrophizing, separately characterized by sex. Interaction terms (such as pain intensity*pain catastrophizing) were used in moderation analyses, intended to determine whether the prognostic value of predictors such as pain intensity and pain catastrophizing in predicting opioid prescription were mutually dependent. In simpler terms, this interaction term was intended to reflect whether the independent prognostic value of pain intensity for opioid prescription was dependent on co-occurring pain catastrophizing scores, and vice-versa.

We also employed mediation analyses, an analytic approach designed to estimate the extent to which a third variable (the “mediator’) explains or accounts for the relationship between an independent and dependent variable. Given the known positive relationships between pain intensity and pain catastrophizing and the inconsistent relationship between pain catastrophizing and opioid use, one natural question that arose was whether the relationship between pain intensity and opioid use was mediated by pain catastrophizing. To test this, we used the causal mediation analysis framework from Imai et al for the whole sample and separately for males and females.37 Analogous to mediation analysis using structural equation modeling, this framework also relies on a series of regression models. It is able to estimate the average causal mediated effect and average direct effect non-parametrically.

All statistical analyses were completed in SPSS© (SPSS 22) and R© (R-3.1.0) for Windows. General additive models were estimated using the R package .mgcv. Significance was set at p < 0.05 unless otherwise noted.

3. Results

3.1. Sample demographic and diagnostic characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the 1794 patients included in this study are described in Table 1. The study sample was predominantly white (n=1144, 67%), married (n=794; 54%), female (n=1129, 63%) with at least some college education (n=1199; 83%). Mean age of the sample was about 50 years (Table 2) with an age ranged of 18 to 94 (Table 1). In the current study, pain diagnoses were separated into a series of categories, representing the broad location and presumed etiology of pain complaints. Given that complete diagnostic information was not available for the sample used in this study, pain diagnosis information for all pain clinic patients presenting for an initial visit between January 2014 and May 2016 were analyzed to characterize the clinic overall. While 10,707 (28%) of the total number of diagnoses were not pain related or listed, the most common diagnoses included headache (9.2%), thoracolumbar pain (8.7%), musculoskeletal pain (7.6%), cardiac pain (5.3%), and nerve pain (5.0%) (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, which lists the distribution of pain diagnoses for the clinic). The total number of diagnoses exceeded the number of patients visiting the clinic due to multiple diagnoses per patient per visit. Most patients had one major pain diagnosis (46%) while close to 20% had two or more diagnoses.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 1129 (63) |

| Male | 665 (37) |

| Age | |

| 18–30 | 216 (12) |

| 31–40 | 301 (17) |

| 41–50 | 373 (21) |

| 51–60 | 475 (26) |

| 61–70 | 256 (14) |

| 71–80+ | 173 (10) |

| Marital Status* (19% of patients not included) | |

| Separated/divorced | 225 (16) |

| Cohabitating | 104 (7) |

| Widowed | 49 (3) |

| Married | 794 (54) |

| Never married | 288 (20) |

| Education* (19% of patients not included) | |

| No high school diploma | 111 (8) |

| High school diploma or GED | 143 (10) |

| Some university/Associate’s degree | 534 (37) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 343 (24) |

| Graduate degree | 322 (22) |

| Unknown | 4 (≪1) |

| Race*§ (5% of patients not included) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 7 (≪1) |

| Asian | 117 (7) |

| Black or African American | 51 (3) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 16 (1) |

| White | 1144 (67) |

| Other | 311 (18) |

| Patient declined to answer | 34 (2) |

| Unknown | 31 (2) |

Not all patients included due to incomplete surveys.

Due to limitations of the electronic medical records used, ethnicity data were unreliable and not reported. Hispanic is subsumed either in “White” or “Other”.

Table 2.

Clinical measures by sex

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Age | 51 (15) | 49 (15)* |

| Average Pain Intensity (NRS) | 6 (2) | 6 (2)* |

| PCS | 21 (13) | 20 (13) |

| Depression | 57 (10) | 58 (9) |

| Anxiety | 58 (10) | 59 (9)* |

Scores are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Note: Stars denote significant sex differences on a variable:

p < 0.05

3.2. Clinical measures by sex

Clinical measures are reported by sex in Table 2. Unpaired t-test results revealed a slight age difference between males and females, with males having greater average age. As expected, females had higher average pain intensity than males (p = 0.02). Despite higher pain intensity in females, we found no difference in PCS scores by sex (p = 0.12). Although there were no significant differences in depression between males and females, there was a difference in anxiety between the sexes, with females reporting greater anxiety.

3.3. Clinical measures by opioid status

Means for age and psychometric variables are reported in Table 3. In the full sample, 57% (n = 1,020) had one or more opioid prescriptions. Age was unrelated to opioid prescription. A similar proportion of males (58%, n = 387) and females (56%, n = 633) had opioid prescription (p = 0.38). Overall, opioid prescription was associated with higher average pain intensity (p < 0.001), PCS scores (p < 0.001), and depression (p = 0.04).

Table 3.

Clinical measures by opioid status

| Full Sample | No Opioids | Opioids | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Age | 50 (15) | 49 (16) | 50 (15) |

| Average Pain Intensity | 6 (2) | 5 (2) | 6 (2)** |

| PCS | 20 (13) | 19 (13) | 21 (13)** |

| Depression | 58 (9) | 57 (9) | 58 (10)* |

| Anxiety | 58 (10) | 58 (10) | 59 (9) |

Scores are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Note: Stars denote significant differences between opioid and non-opioid groups:

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

3.4. Opioid prescription as a function of pain intensity and pain catastrophizing

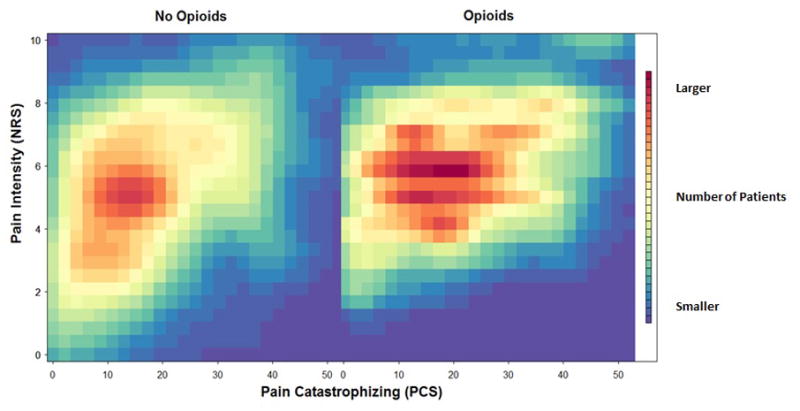

Given the significant differences in pain intensity and pain catastrophizing observed between opioid prescription groups, we sought to attain a preliminary understanding of any underlying relationships through a visual display – a density plot of patients by opioid prescription status. Figure 1 displays a heat map of the density of patients according to opioid status as a function of pain intensity and pain catastrophizing, with red representing the greatest patient density. As seen by the concentration of yellow at the bottom left-hand corner of the left graph, the density of patients with low levels of pain and catastrophizing in those without opioid prescription is much higher than that of those with opioid prescription. Those with opioid prescription have a more horizontal distribution of patients with a wider range of pain catastrophizing. Also, there are a greater number of high patient-density patches spread over a larger range of catastrophizing. The data display in Figure 1 allowed us to visually detect emerging relationships between pain intensity and pain catastrophizing in those without opioid prescription. However, the difference between the heat maps of the two groups called for the further modeling of these variables.

Figure 1.

Heat map of distribution of patients in terms of pain catastrophizing and pain intensity, by opioid prescription status. The color red represents the greatest patient density.

3.5. Generalized linear modeling of the association between opioid prescription, average pain intensity, and additional variables

We further investigated the differences in pain intensity and pain catastrophizing seen between opioid users and non-users with a more sophisticated analysis, generalized linear modeling. Table 4 shows the result of using generalized linear modeling, a more flexible linear model, to show the association between opioid prescription, average pain intensity, and additional study variables. As a base model, pain intensity showed a significant positive association with opioid prescription. For every increase of one standard deviation away from average pain intensity, the odds of having prescription opioids increased by 41%. Using pain intensity with other variables showed no significant effects on opioid prescription. However, upon modeling opioid prescription with pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and their interaction term, significant associations were found. Pain intensity and pain catastrophizing independently yielded high odds ratios (1.66 and 1.56 respectively), but their interaction term, which introduced a greater degree of symmetric flexibility to the model, yielded odds ratios of about one (0.91 for PCS term, 0.98 for pain intensity term). Although the odds ratios were close to one, the p-value of the interaction term was low (p = 0.005), indicating the presence of some significant variable overlap that merited more nuanced analysis.

Table 4.

General linear models for the prediction of opioid prescription

| Variable | Estimate | OR (per SD) | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model

| |||||

| 1 | Pain Intensity | 0.159 | 1.41 | 0.023 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Models with One Additional Predictor

| |||||

| 2 | Anxiety | −0.001 | 0.99 | 0.006 | 0.834 |

|

| |||||

| 3 | Depression | 0.003 | 1.03 | 0.006 | 0.643 |

|

| |||||

| 4 | Age | 0.004 | 1.06 | 0.003 | 0.195 |

|

| |||||

| 5 | Female | −0.131 | 0.88 | 0.101 | 0.192 |

|

| |||||

| 6 | PCS Score | 0.006 | 1.08 | 0.004 | 0.109 |

|

| |||||

| Model with PCS and interaction

| |||||

| 7

|

Pain Intensity | 0.236 | 1.66 | 0.041 | < 0.001 |

| PCS Score | 0.034 | 1.56 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |

| PCS:Pain Intensity | −0.007 | 0.91 (PCS) | 0.002 | 0.005 | |

| 0.98 (Pain Int.) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Model with PCS and interaction by sex

| |||||

| 8 Males

|

Pain Intensity | 0.32 | 2.03 | 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| PCS Score | 0.032 | 1.53 | 0.017 | 0.057 | |

| PCS:Pain Intensity | −0.006 | 0.92 (PCS) | 0.003 | 0.039 | |

| 0.99 (Pain Int.) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 9 Females

|

Pain Intensity | 0.202 | 1.53 | 0.051 | < 0.001 |

| PCS Score | 0.035 | 1.57 | 0.013 | 0.008 | |

| PCS:Pain Intensity | −0.005 | 0.94 (PCS) | 0.002 | 0.032 | |

| 0.99 (Pain Int.) | |||||

Note: Models were computed using blocks of predictors in predicting opioid prescription. First, pain intensity was tested as an independent predictor. Next, psychological and demographic factors were added. Third, pain intensity and pain catastrophizing scores and an interaction between these variables were estimated for the entire sample, as well as separately in males and females.

Although we had found no sex differences in catastrophizing or opioid prescription status in our initial stages of analysis, differences in pain intensity between sexes prompted further analyses. The generalized linear models revealed pain intensity to be the best predictor for opioid prescription in both males and females. While the overall model showed sex differences in the effect of pain catastrophizing on the prediction of opioid prescription, it also revealed the interaction between pain catastrophizing and pain intensity to have significant predictive effects in both sexes (p=0.039 in males, p=0.032 in females). Given that these relationships existed when analyzing the entire sample as well as when analyzing the sample by sex, we next aimed to characterize the potential mediators underlying these interactions.

3.6. Test of the moderating effect of opioid prescription on the relationship between pain intensity and pain catastrophizing

Given the existence of a relationship between opioid prescription, pain intensity, and pain catastrophizing, we examined potential mediators of these linear associations. As seen in Table 5, the direct effect of pain intensity on opioid prescription was greater than the mediated effect of PCS on the relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription in both sexes. The non-significant p-values indicated that PCS did not mediate, or explain, the relationship between opioid prescription and pain intensity evidenced in the linear modeling analysis. This lack of mediation suggested that pain catastrophizing had a moderating effect on the relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription. In other words, pain catastrophizing strengthened, rather than explained, their linear relationship. Furthermore, mediation analysis also revealed that sex serves as a moderating variable.

Table 5.

Pain intensity and opioid prescription by sex and the mediation effect of PCS

| Total Effect | Direct Effect of Pain Intensity on Opioid Prescription | PCS Mediation of the Effect of Pain Intensity on Opioid Prescription | Proportion | P-value for Mediated Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | 0.164 | 0.151 | 0.014 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Male | 0.218 | 0.217 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.95 |

| Female | 0.136 | 0.119 | 0.017 | 0.120 | 0.09 |

Note: This analysis involved using pain intensity and pain catastrophizing scores as predictors of opioid prescription. Pain catastrophizing scores were tested as a statistical mediator of the relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription. Proportion column refers to proportion of direct effect of pain intensity on opioid prescription accounted for by PCS scores.

To further elucidate potential moderators of the relationship between sex, opioid prescription, pain intensity, and pain catastrophizing, we employed general additive modeling to visualize any complex non-linear relationships. Additive modeling p-values revealed significant effects of opioid prescription on the relationship between pain intensity and catastrophizing in the entire sample (p<0.001). However, a non-linear model as provided by general additive modeling did not fit the interactions between pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and opioid prescription in females (p=0.005) as well as it did in men (p<0.001). This reveals that the relationship between these variables may be different for male and female patients, leading to the conclusion that sex moderates the relationship between pain intensity, catastrophizing, and opioid prescription.

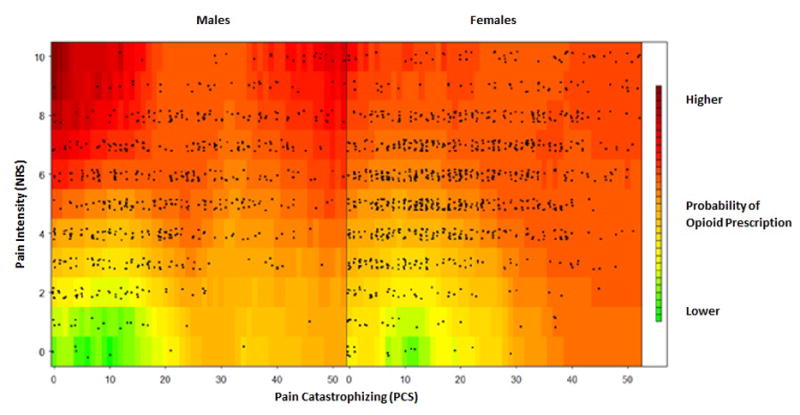

Figure 2 (green represents lower density of patients with opioid prescription, and red represents high density of patients with opioid prescription) shows that, as expected, in both males and females, low pain intensity and pain catastrophizing were associated with patients without opioid prescription. However, moving past the lower left-hand corner of both graphs in Figure 2, the graphs shows that in males, the greatest density of patients with opioid prescription is found in those with high pain intensity and low pain catastrophizing. Paradoxically, males with high pain intensities and high catastrophizing scores did not seem to have higher frequencies of opioid prescription. However, for females, opioid prescription was associated with both high pain intensity as well as high pain catastrophizing. Overall, there was a strong non-linear relationship between pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and opioid prescription in males, as seen by the horizontal gradations of increasing opioid prescription upon increases in pain intensity. Given the increased density of females with opioid prescription who have high pain intensities and high levels of catastrophizing, there seems to be a more nuanced relationship between pain, pain catastrophizing, and opioid prescription in this group. Figures 3 and 4 represent these sex-dependent relationships.

Figure 2.

Non-linear relationship between pain intensity and pain catastrophizing, by sex.

Note: Points represent individual patients.

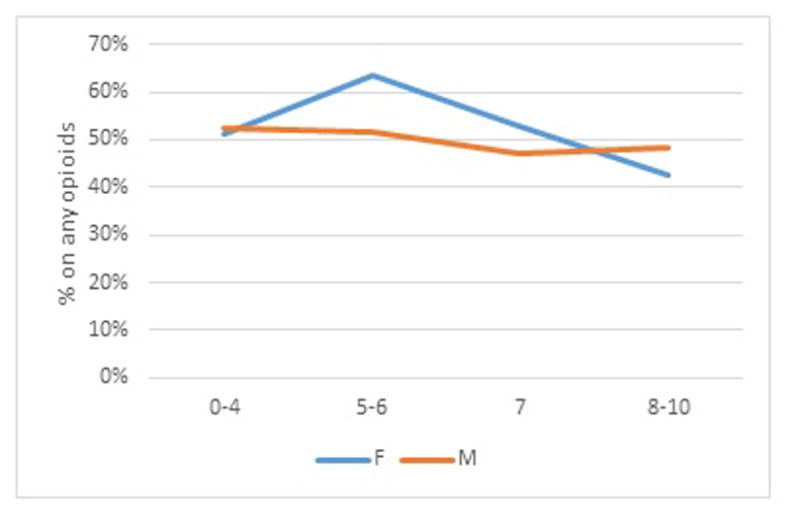

Figure 3.

Relationship between opioid prescription (Y axis; % sample prescribed any opioids) and pain intensity quartile (X axis; 0–10 pain intensity ratings) by sex.

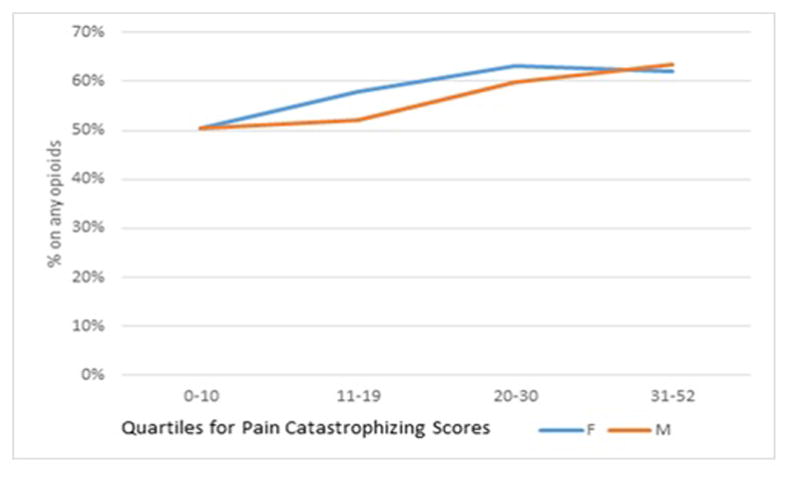

Figure 4.

Relationship between opioid prescription (Y axis; % of sample prescribed any opioids) and quartiles of pain catastrophizing scores (X axis) by sex.

Figure 3 reveals that males have a relatively flat association between opioid prescription and pain intensity, the female data suggests an inflection point on the numeric rating scale that emerges above pain intensity of 4 and persists until roughly pain intensity ratings of 7.

Figure 4 reveals that opioid prescription by sex diverges above scores of 10 on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and similarly persists until the severe range of catastrophizing is reached, at which point the associations align for both sexes. Combined, Figures 3 and 4 suggest that sensory and psychological experience appear to associate more strongly with opioid prescription at lower levels (intensities) for females than for males.

Finally, to address concerns about model flexibility and cross-validation of our findings, we performed a bootstrapping on the general additive model fitting and the statistical inference using 500 replicates. All of the smoothed term p-values in the bootstrap replicates were < 0.05. In fact, the largest (least significant) p-value was 0.0001. This suggests that the non-linearity effect we described is highly robust.

4. Discussion

In this study, we characterized the relationship between opioid prescription, pain intensity, and pain catastrophizing in 1794 patients with chronic pain seeking initial medical evaluation at a multidisciplinary pain treatment center. Univariate analysis revealed that active opioid prescription was significantly associated with greater pain catastrophizing and higher pain intensity. Linear modeling revealed that: 1) pain intensity was directly and significantly related to opioid prescription; 2) a significant interaction effect was found for pain catastrophizing and pain intensity on opioid prescription; and 3) this interaction effect remained significant yet differed by sex. Mediation analysis showed no mediating effects of pain catastrophizing or sex. In turn, catastrophizing and sex demonstrated moderating roles in the relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription. Furthermore, additive modeling showed nuanced non-linear relationships between the aforementioned variables in both males and females. Pain catastrophizing had greater association with opioid prescription in females. While we could not make causal inferences due to the cross-sectional study design and opioid prescription being an outcome of previous clinic visit, nor would we be able to make these inferences had we identified any significant mediated effects in our analyses, our data reveal sex-based differences in the relationship between pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and opioid prescription, highlighting the impact that catastrophizing may have in females with chronic pain.

Pain catastrophizing relates directly to pain intensity and serves to undermine pain treatment efficacy.38 Similarly, pain intensity directly relates to opioid use.39–41 Here we show that opioid prescription is associated with greater pain catastrophizing. Notably, our univariate analysis of this large sample showed no significant sex differences in pain catastrophizing or opioid prescription. Prior studies have shown inconsistent relationships between sex and pain catastrophizing,42–44 making it unclear whether or not these discrepancies are a result of smaller sample sizes.30 Consistent with prior work, we found greater average pain intensity for females.45

The sex- and opioid status-based differences in pain and catastrophizing called for linear modeling to elucidate any underlying relationships between these variables. Our results showed that pain intensity was highly associated with the likelihood of having prescription opioids. However, adding pain catastrophizing and an interaction between catastrophizing and pain intensity demonstrated the strongest linear association with opioid prescription. Mediation analysis suggested that pain catastrophizing and sex served as moderating variables, strengthening the existing relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription.

In addition to showing the moderating characteristics of pain catastrophizing and sex, we used additive modeling to show the impact of pain catastrophizing on opioid prescription by sex. For men, the greatest density of individuals with opioid prescription was co-located with lower pain catastrophizing and higher pain intensity. In females, however, the greatest density of those with opioid prescription was co-located with moderate to high pain intensities and pain catastrophizing levels, suggesting that pain catastrophizing has a stronger association with opioid prescription status. Given that opioids were prescribed prior to the study, causal inferences are impossible, but future studies may employ prospective designs to confirm that these associations hold at the point of opioid prescription.

Our findings suggest that even relatively low levels of negative cognitive and emotional responses to pain may have a greater impact on opioid prescribing in females. Females may be more likely to influence provider prescribing patterns through behavioral cues during the medical visit; prior research has suggested females may engage in pain behavior for extended periods of time46 and may appraise their pain as more threatening than males.47 While treatment for catastrophizing is important for both sexes, the higher additive modeling p-values found for females suggests that risks are occurring at lower levels of catastrophizing for females than for males.

Additional studies are needed to replicate the associations we discovered. However, if confirmed, these findings would hold specific clinical relevance. Often, a pain catastrophizing scale score is considered clinically meaningful if it is near or over 30.27 However, given the moderating effect of pain catastrophizing and its possible predictive value for opioid prescription, treatments for pain catastrophizing may hold specific therapeutic value for females at levels considered clinically subthreshold for outpatients with chronic pain (e.g., PCS <20). Others have recently demonstrated catastrophizing risk inflection points occurring at similarly low levels of catastrophizing for outpatient pain rehabilitation outcomes (PCS >14)48 and postsurgical pain (PCS > 13)16, thereby suggesting the need for continued examination of how the field defines threshold for risk and treatment needs. We found no other studies to specifically report subthreshold associations with opioid prescription and sex differences therein.

Strengths & Limitations

Our study design involved single time-point data collection, which allowed for descriptive associations only, with no possibility for causal interpretations. Many of our variables, including about 40% of our opioid use data, were collected directly from medical records. For the 700 patients whose opioid use was collected manually from the electronic medical record, opioid dose was collected. After meticulous data cleaning and the calculation of opioid dose in morphine equivalents, opioid dosing information from the electronic medical records proved to be unreliable. Given that chart review was completed only for initial pain clinic visits, and given that not all physicians asked for non-pain-related medications, the accuracy of prescription and dosing of other medications, such as benzodiazepines, was also unreliable. We therefore structured our study to describe associations with opioid prescription and did not characterize relationships based on opioid dose or other medications.

Due to the de-identified nature of the data extracted from Pain-CHOIR, we were unable to attain the medical record numbers of all patients included in this study. For a third of the sample, we were able to locate medical record numbers by identifying exact data matches between our data set and that of Pain-CHOIR. Despite having only a small proportion of this sample’s diagnostic codes, we believe that a comparison of these patients with the distribution of the entire pain clinic population is sufficient in characterizing the population, especially given that we did not use the diagnostic information for any significant analyses.

Despite the use of single time-point data, the electronic and easily-accessible nature of the data allowed for the application of novel analytics on a large database, yielding more nuanced characterizations of the population. In addition to mediation analysis, we employed highly flexible, linear and non-linear models, which together, presented a novel battery of rigorous statistical tests that allowed for optimal characterization of the data.

Future Directions

Although our results are informative, the nature of some variables merit closer investigation. Given the limitation of using opioid prescription as a binary variable for measuring opioid use, future investigations should include opioid dose and possibly more reliable methods of opioid consumption quantification, such as a urine screen. Further investigation by pain condition or of other drugs that have shown relevance to opioid use, such as benzodiazepines, is also warranted.

Prospective, longitudinal studies are also needed to characterize patients at the point of opioid prescription. Moreover, despite our use of several important covariates, our analysis was not exhaustive. Consequently, there may be other variables (e.g., pain sensitivity, pain-related disability, and pain interference) that are relevant to pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and opioid use.

As a learning health care system,25,26 Pain-CHOIR allowed for an inclusive range of pathology and patient characteristics that are not typical of most research studies or even registries that tend to be disease-specific. As such, it necessarily included wide ranges of patient characteristics and, more importantly, complex co-relative relationships across the entire spectra of pathology. While traditional linear model based methods are valid and appropriate in studies with traditional data ascertainment, in all-comer learning health systems such as CHOIR, models with reduced restrictions about inter-variable relationships should be more methodologically appropriate. In this work, we demonstrated that flexible models, such as additive models, can elucidate non-linear relationships between several variables that are core to our field. In fact, these models suggest additional behavior-changing threshold effects that would be obscured in traditional methods. While these methods are technically not new and have been in use in other fields of science, they have not seen wide utilization in the field of pain. Again, it is the all-encompassing nature of CHOIR that enables methods like this. Reciprocally, CHOIR and its clinical and research values are enabled by such methods.

Conclusions

This study utilized a large dataset of patients visiting a tertiary outpatient pain clinic. We elucidated relationships between sex, pain catastrophizing, pain intensity, and opioid prescription. Using an advanced analytic approach, we found a significant relationship between pain intensity and opioid prescription and found that this relationship was significantly stronger in females, especially those with high levels of pain catastrophizing. Despite similar levels of catastrophizing and opioid prescription among males and females, pain catastrophizing appears to have a stronger relationship with opioid status for females, calling for future studies to investigate lower pain catastrophizing thresholds for females and the potential impacts for reducing opioid prescription. These results emphasize the importance of considering both obvious medical factors such as pain intensity and psychological and demographic differences that may be salient predictors of the use of prescription opioids.

Supplementary Material

Summary Statement.

In a sample of tertiary care patients with chronic pain, the relationships between pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and opioid prescription vary significantly between males and females.

Acknowledgments

Funding

We acknowledge funding support from National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) P01AT006651 (SCM) and P01AT006651S1 (SCM and BDD); (NCCIH) R01 AT008561-01A1 (BDD and SCM); NIH National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) K24DA029262 (SCM) and 3T32DA035165-02S1 (JAS); NIH Pain Consortium HHSN271201200728P (SCM); and from the Chris Redlich Pain Research Endowment (SCM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, Angermeyer MC, Borges GL, Bromet EJ, Demytteneare K, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Lepine JP, Haro JM, Levinson D, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Seedat S, Watanabe M. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008;9:883–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Committee on Advancing Pain Research Care. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Institute of Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keefe FJ, Brown GK, Wallston KA, Caldwell DS. Coping with rheumatoid arthritis pain: catastrophizing as a maladaptive strategy. Pain. 1989;37:51–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Cortical responses to pain in healthy individuals depends on pain catastrophizing. Pain. 2006;120:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gracely RH, Geisser ME, Giesecke T, Grant MA, Petzke F, Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain. 2004;127:835–43. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Severeijns R, Vlaeyen JW, van den Hout MA, Weber WE. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity, disability, and psychological distress independent of the level of physical impairment. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:165–72. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan MJ, Lynch ME, Clark AJ. Dimensions of catastrophic thinking associated with pain experience and disability in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pain. 2005;113:310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, Kirsch I. Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain. 2001;91:147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martel MO, Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Edwards RR. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:335–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morasco BJ, Turk DC, Donovan DM, Dobscha SK. Risk for prescription opioid misuse among patients with a history of substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll I, Barelka P, Wang CK, Wang BM, Gillespie MJ, McCue R, Younger JW, Trafton J, Humphreys K, Goodman SB, Dirbas F, Whyte RI, Donington JS, Cannon WB, Mackey SC. A pilot cohort study of the determinants of longitudinal opioid use after surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:694–702. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31825c049f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hah JM, Mackey S, Barelka PL, Wang CK, Wang BM, Gillespie MJ, McCue R, Younger JW, Trafton J, Humphreys K, Goodman SB, Dirbas FM, Schmidt PC, Carroll IR. Self-loathing aspects of depression reduce postoperative opioid cessation rate. Pain Med. 2014;15:954–64. doi: 10.1111/pme.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papaioannou M, Skapinakis P, Damigos D, Mavreas V, Broumas G, Palgimesi A. The role of catastrophizing in the prediction of postoperative pain. Pain Med. 2009;10:1452–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janda AM, As-Sanie S, Rajala B, Tsodikov A, Moser SE, Clauw DJ, Brummett CM. Fibromyalgia survey criteria are associated with increased postoperative opioid consumption in women undergoing hysterectomy. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:1103–11. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlin DJ, Sullivan MJ, Freund PR, Roesen K. Catastrophizing: a risk factor for postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banka TR, Ruel A, Fields K, YaDeau J, Westrich G. Preoperative predictors of postoperative opioid usage, pain scores, and referral to a pain management service in total knee arthroplasty. HSS Journal®. 2015;11:71–75. doi: 10.1007/s11420-014-9418-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helmerhorst GT, Vranceanu AM, Vrahas M, Smith M, Ring D. Risk factors for continued opioid use one to two months after surgery for musculoskeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:495–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martel MO, Jamison RN, Wasan AD, Edwards RR. The association between catastrophizing and craving in patients with chronic pain prescribed opioid therapy: a preliminary analysis. Pain Med. 2014;15:1757–64. doi: 10.1111/pme.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovejoy TI, Dobscha SK, Turk DC, Weimer MB, Morasco BJ. Correlates of prescription opioid therapy in Veterans with chronic pain and history of substance use disorder. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2016;53:25–36. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2014.10.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arteta J, Cobos B, Hu Y, Jordan K, Howard K. Evaluation of How Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Relationship between Pain Catastrophizing and Prescription Opioid Misuse in a Chronic Pain Population. Pain Med. 2016;17:295–303. doi: 10.1111/pme.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Unutzer J. Regular use of prescribed opioids: association with common psychiatric disorders. Pain. 2005;119:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell CM, McCauley L, Bounds SC, Mathur VA, Conn L, Simango M, Edwards RR, Fontaine KR. Changes in pain catastrophizing predict later changes in fibromyalgia clinical and experimental pain report: cross-lagged panel analyses of dispositional and situational catastrophizing. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R231. doi: 10.1186/ar4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granot M, Ferber SG. The roles of pain catastrophizing and anxiety in the prediction of postoperative pain intensity: a prospective study. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:439–45. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000135236.12705.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kao M, Weber S, Cook K, Olson G, Pacht T, Darnall B, Weber S, Mackey S. Stanford-NIH Pain Registry: Open source platform for large-scale longitudinal assessment and tracking of modern patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Pain. 2014;15:S40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackey S, Kao MC, Cook K, Olson G, Pacht T, Darnall B, Weber SC. Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR): Open source platform for large-scale clincal outcomes measurement to support learning healthcare systems (poster presentation). PAINWeek; 2014; Las Vegas, NV. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook K, Devellis R, DeWalt D, Fries JF, Gershon R, Hahn EA, Lai JS, Pilkonis P, Revicki D, Rose M, Weinfurt K, Hays R, Group PC. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Damme S, Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Goubert L, Van Houdenhove B. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale: invariant factor structure across clinical and non-clinical populations. Pain. 2002;96:319–24. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osman A, Barrios FX, Gutierrez PM, Kopper BA, Merrifield T, Grittmann L. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: further psychometric evaluation with adult samples. J Behav Med. 2000;23:351–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1005548801037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, Hauptmann W, Jones J, O’Neill E. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med. 1997;20:589–605. doi: 10.1023/a:1025570508954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:125–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelen MO, Reeve BB. Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):5–18. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, Group PC. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18:263–83. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010;15:309–34. doi: 10.1037/a0020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forsythe ME, Dunbar MJ, Hennigar AW, Sullivan MJ, Gross M. Prospective relation between catastrophizing and residual pain following knee arthroplasty: two-year follow-up. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:335–41. doi: 10.1155/2008/730951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eriksen J, Sjogren P, Bruera E, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Critical issues on opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: an epidemiological study. Pain. 2006;125:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciccone DS, Just N, Bandilla EB, Reimer E, Ilbeigi MS, Wu W. Psychological correlates of opioid use in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain: a preliminary test of the downhill spiral hypothesis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:180–92. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: results from a national, population-based survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, Ray GT, Saunders K, Sullivan MD, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Silverberg MJ, Boudreau D, Satre DD, Von Korff M. Age and gender trends in long-term opioid analgesic use for noncancer pain. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:2541–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsells Kelly J, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138:507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung L. Pain catastrophizing: an updated review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:204–17. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–67. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan M, Tripp DA, Santor D. Gender differences in pain and pain behavior: the role of catastrophizing. Cog Ther Res. 2000;24:121–34. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Unruh AM, Ritchie J, Merskey H. Does gender affect appraisal of pain and pain coping strategies? Clin J Pain. 1999;15:31–40. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ. Clinically Meaningful Scores on Pain Catastrophizing Before and After Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation: A Prospective Study of Individuals With Subacute Pain After Whiplash Injury. Clin J Pain. 2013 doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31828eee6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.