Abstract

Background

The natural course and clinical significance of delirium in the emergency department (ED) is unclear.

Objectives

We sought to 1) describe the extent to which delirium in the ED persists into hospitalization (ED delirium duration) and 2) determine how ED delirium duration is associated with 6-month functional status and cognition.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

Tertiary care, academic medical center

Participants

ED patients ≥ 65 years old who were admitted to the hospital

Measurements

The modified Brief Confusion Assessment Method was used to ascertain delirium in the ED and hospital. Premorbid and 6-month function were determined using the Older American Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living (OARS ADL) questionnaire which ranged from 0 (completely dependent) to 28 (completely dependent). Premorbid and 6-month cognition were determined using the short form Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) which ranged from 1 to 5 (severe dementia). Multiple linear regression was performed to determine if ED delirium duration was associated with 6-month function and cognition adjusted for baseline OARS ADL and IQCODE, and other confounders.

Results

A total of 228 older ED patients were enrolled. Of the 105 patients who were delirious in the ED, 81 (77.1%) patients’ delirium persisted into hospitalization. For every ED delirium duration day, the 6-month OARS ADL decreased by 0.63 points (95%CI: −1.01 to −0.24), indicating poorer function. For every ED delirium duration day, the 6-month IQCODE increased 0.06 points (95%CI: 0.01 to 0.10) indicating poorer cognition.

Conclusions

Delirium in the ED is not a transient event and frequently persists into hospitalization. Longer ED delirium duration is associated with an incremental worsening of 6-month functional and cognitive outcomes.

Keywords: delirium, emergency department, long-term function, long-term cognition

Introduction

Delirium is a form of acute brain failure that affects 8 to 17% of older emergency department (ED) patients,1,2 and is associated with higher mortality1 and prolonged hospitalizations.3 The ED plays a central role in the US healthcare system and is the gateway for the majority of hospital admissions,4 yet several knowledge gaps about delirium’s impact in this unique setting exist. First, it is unclear how frequently delirium in the ED persists into hospitalization. Most delirium studies conducted in the ED typically assess for delirium at a single point in time.5 Second, the effect of delirium in the ED on long-term outcomes is unclear especially as it relates to long-term function and cognition, which are critical components to the older patient’s quality life. Most delirium outcome studies have been conducted in the inpatient setting and may have limited generalizability to the ED. The ED is a much more diverse environment representing patients with a wide variety of disease states (including illness severity) across different subspecialties (e.g., surgery, neurology, orthopedic surgery, etc.). These studies also typically enrolled patients within the first 48 hours of hospitalization and the patient’s delirium status at the time of enrollment may not have reflected the patient’s ED delirium status.6–10 Third, it is unclear if prolonged episodes of delirium are associated with poorer long-term function and cognition. Despite delirium’s heterogeneity, most outcome studies conducted have dichotomized delirium as a present-absent event. As a result, this study sought to 1) describe the extent in which delirium in the ED persists into hospitalization (ED delirium duration) and 2) determine how ED delirium duration is associated with 6-month function and cognition.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This was a prospective cohort study conducted at a tertiary care, academic hospital. The local institutional review board reviewed and approved this study.

Selection of Participants

Patients were enrolled from the ED between March 2012 and November 2014. Consecutive enrollment occurred Monday through Friday at four randomly selected 4-hour blocks per week (8A –12P, 10A – 2P, 12P – 4P, 2P – 6P). Patients were included if they were 65 years or older, in the ED for less than four hours at the time of enrollment, and unlikely to be discharged home according to the ED physician. Patients were excluded if they were non-English speaking, previously enrolled, deaf, comatose, non-verbal or unable to follow simple commands prior to their current illness, were considered unsuitable for enrollment by the treating physician or nurse, were unavailable for enrollment with the 4-hour time limit, or were discharged home from the ED.

Because 83% to 92% of older ED patients are non-delirious,1,2 all delirious and one out of six randomly selected non-delirious older ED patients were enrolled to maximize the feasibility of our study. Randomization was determined by a computerized random-number generator. Non-delirious ED patients were included to serve as controls, to represent the full spectrum of acute brain dysfunction, and to increase statistical power for analyses; 38.2% of non-delirious ED patients had features of delirium without meeting full criteria (subsyndromal delirium).

Methods of Measurement

Delirium was assessed in the ED at the time of enrollment (0 hours) and at 3 hours and daily during the hospitalization for 7 consecutive days after the ED visit or until hospital discharge, whichever came first. A patient was considered to be delirious in the ED if either the 0- or 3-hour delirium assessment was positive. If the patient was hospitalized more than 7 days, another delirium assessment was performed at hospital discharge. In-hospital delirium assessments occurred daily (usually in the morning) 7 days a week. The primary independent variable was the total number of days a delirious ED patient remained delirious throughout the hospitalization (ED delirium duration); the ED delirium episode was considered resolved if the patient was non-delirious for two consecutive days. Patients who were initially non-delirious in the ED were assigned an ED delirium duration of 0 days even if they later developed delirium during hospitalization; those who subsequently developed delirium during hospitalization were considered to have incident delirium. Similarly, for those who were delirious in the ED, but had another episode of delirium after resolution, these patients were also considered to have incident delirium.

In non-mechanically ventilated patients, trained research assistants (RAs) ascertained delirium using a modified version of the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM) which is a brief (< 2 minutes) delirium assessment designed for use by non-physicians in the ED setting.11 In older ED patients, the modified bCAM is 82% to 86% sensitive and 93% to 96% specific for delirium as diagnosed by a psychiatrist and its kappa is 0.87 indicating excellent inter-observer reliability.11 In mechanically ventilated patients, the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) was used to ascertain delirium, and is 93% to 100% sensitive, 98% to 100% specific for delirium, and has a kappa of 0.96 indicating excellent interobserver reliability.12

The primary outcome variables were 6-month function and cognition adjusted for their baseline. Function was assessed for using the Older American Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living (OARS ADL) questionnaire to establish premorbid (baseline) and 6-month functional status.13 This scale ranged from 0 (completely dependent) to 28 (completely independent). This was preferably completed by an informant who knew the patient well, but the patient was allowed to complete the OARS ADL if no informant was available and if he/she was capable of providing informed consent. Premorbid (baseline) and 6-month cognition was measured using the short form Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE).14 This informant-based cognitive screen was used because global tests of cognition would not accurately reflect premorbid cognition during a delirium episode. It has been previously used to assess for cognitive decline.15 The IQCODE was only completed by informants who knew the patient for at least 10 years. The IQCODE ranged from 1 (markedly improved cognition) to 5 (markedly worse cognition, severe dementia), where a score of 3 represented no change in cognition. To establish premorbid measures, OARS ADL and IQCODE were obtained in the ED at the time of enrollment; patients and/or their surrogates were asked to rate the patient’s function or cognition 2 weeks prior to the ED visit. An RA who was blinded to the ED and hospital delirium assessments determined 6-month function and cognition using phone follow-up. Every attempt was made to obtain these 6-month assessments from the same person who completed the premorbid assessments. The RA and the person completing the 6-month OARS ADL and IQCODE did not have access to the premorbid assessments.

Average daily alcohol consumption prior to the acute illness was collected by patient or surrogate interview. Medical record review was performed to collect dementia status, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, home benzodiazepine or opioid medication use, and the presence of a central nervous system diagnosis. A patient was considered to have dementia if they had: (i) documented dementia in the medical record, (ii) a premorbid IQCODE greater than a cut-off of 3.38,16 or (iii) prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors prior to admission. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to quantify the patient’s comorbid burden.17 The Acute Physiology Score (APS) of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score was used to quantify severity of illness.18 The presence of a central nervous system (CNS) diagnosis (meningitis, seizure, cerebrovascular accident, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, etc.) was determined by two physician reviewers via medical record review. Any disagreement was adjudicated by a third physician reviewer.

Data Analysis

To determine if ED delirium duration days was independently associated with 6-month function and cognition, multiple linear regression was performed. The 6-month cognition analysis was only conducted in patients who had a baseline and 6-month IQCODE. For the 6-month function outcome, the primary dependent variable was the 6-month OARS ADL and the model was adjusted for premorbid OARS ADL, age, dementia, comorbidity burden (Charlson Comorbidity Index), severity of illness (APS), nursing home residence, incident delirium, and the presence of any CNS diagnosis. For the 6-month cognition model, the primary dependent variable was the 6-month IQCODE and the model was adjusted for premorbid IQCODE, premorbid OARS ADL, age, comorbidity burden (Charlson Comorbidity Index), severity of illness (APS), nursing home residence, incident delirium, and the presence of any CNS diagnosis. These covariates were chosen a priori based upon expert opinion, literature review, and our previous work. We limited the number of covariates incorporated in the multivariable model to avoid overfitting.19

To evaluate the robustness of our multiple linear regression models, we performed a series of sensitivity analyses. We re-ran the multivariable models in a subgroup of patients who were delirious in the ED and in patients whose OARS ADLs were completed by informants only. Because the median hospital length of stay, the proportion of females, non-whites, home ethanol use, and home opiate or benzodiazepine use were different between delirious and non-delirious ED patients, we incorporated these covariates into the regression models. To determine how death may have impacted our findings, we assigned these patients a 6-month OARS ADL of 0 or a 6-month IQCODE of 6, and re-ran the multivariable regression models. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC) and open source R statistical software, version 3.0.2 (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

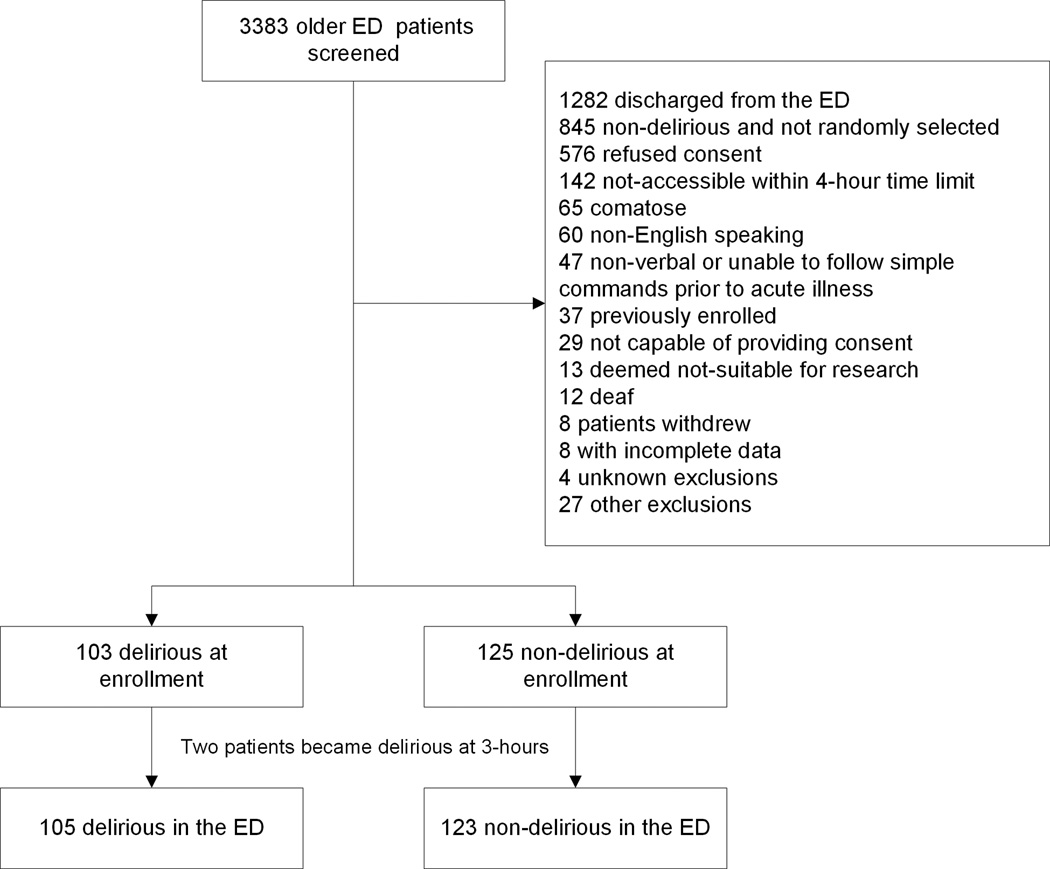

During the study period, 3,383 older ED patients were screened. We enrolled 105 delirious ED patients and a random selection of 123 non-delirious ED patients (Figure 1). Two older patients who were initially non-delirious in the ED became delirious at 3-hours; these patients were considered to delirious in the ED. Table 1 presents patient characteristics stratified by ED delirium status. Of the 105 older patients who were delirious in the ED, 81 (77.1%, 95%CI: 67.7%, 84.5%) remained delirious on hospital day #1. The median (IQR) ED delirium duration was 3 (1, 6) days and 48 (45.7%, 95%CI: 36.1%, 55.7%) remained delirious at hospital discharge.

Figure 1.

Enrollment flow diagram. ED, emergency department. Patients who were non-verbal or unable to follow simple commands prior to the acute illness were considered to have end-stage dementia.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and demographics.

| Non-Delirious Patients n=123 |

Delirious Patients n=105 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median Age (IQR) | 73 (69, 80) | 75 (68, 83) |

|

| ||

| Female gender | 58 (47.2%) | 68 (64.8%) |

|

| ||

| Non-white race | 12 (9.8%) | 18 (17.1%) |

|

| ||

| Nursing home residence | 2 (1.6%) | 5 (4.8%) |

|

| ||

| Average # of daily alcoholic beverage consumption |

||

| 0 | 105 (85.4%) | 100 (95.2%) |

| 1 | 9 (7.3%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| 2 | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| 3 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 5 or more | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (1.0%) |

|

| ||

| Home opioid or benzodiazepine use | 41 (33.3%) | 48 (45.7%) |

|

| ||

| Dementia | 31 (25.2%) | 77 (73.3%) |

|

| ||

| Median (IQR) OARS ADL | 26 (21, 27) | 16 (11, 23) |

|

| ||

| Median (IQR) IQCODE | 3.19 (3.00, 3.56) | 4.06 (3.38, 4.69) |

|

| ||

| Median (IQR) Charlson | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) |

|

| ||

| Median (IQR) APS | 4 (1, 6) | 4 (2, 6) |

|

| ||

| Median (IQR) Hospital LOS | 3 (2, 5) | 5 (3, 8) |

|

| ||

| *Incident Delirium | 12 (9.8%) | 6 (5.7%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, Interquartile range; APS, Acute Physiology Score; ED, emergency department, LOS, length of stay.

Incident delirium were delirium episodes that occurred after an episode of ED delirium resolved (2 consecutive days with negative delirium assessments) or new onset delirium that occurred in those who were not delirious in the ED.

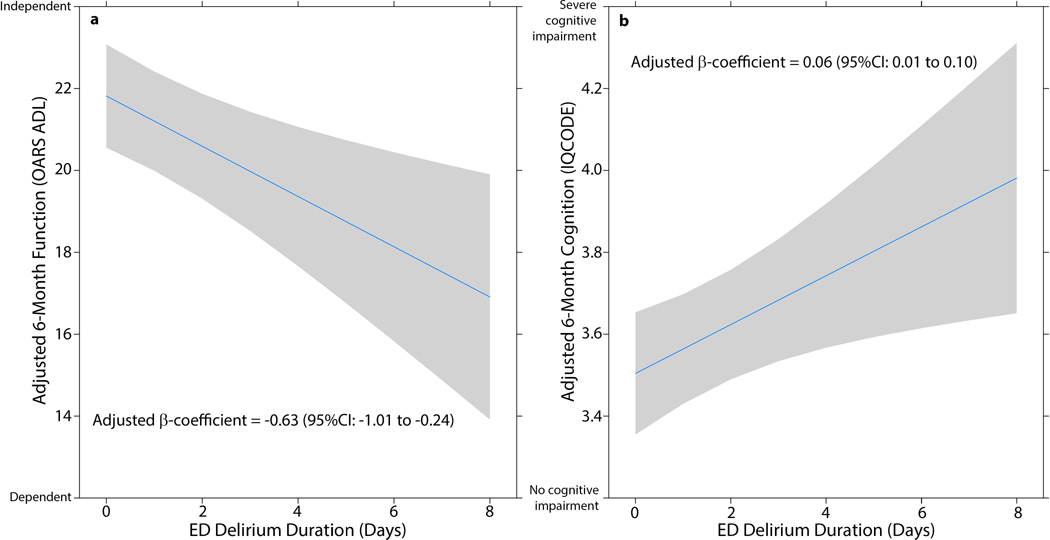

Of the 228 enrolled, all patients had a baseline OARS ADL, 42 (18.4%) patients died within 6-months, 13 (5.7%) patients opted out of the follow-up phone call, and 14 (6.1%) patients were lost to follow-up leaving 159 older ED patients available for ED the delirium duration and 6-month function analysis. For every ED delirium duration day, the patient’s 6-month OARS ADL significantly decreased by 0.63 points (95%CI: −1.01 to −0.24, Figure 2a) after adjusting for premorbid OARS ADL and other confounders. This indicated that longer ED delirium duration was associated with poorer 6-month function.

Figure 2.

a. Relationship between emergency department (ED) delirium duration and 6-month function as measured by the Older American Resources and Services Activities of Daily Living (OARS ADL) scale adjusted for baseline OARS ADL, age, dementia, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, nursing home residence, central nervous system diagnoses, and incident delirium. Lower OARS ADL scores indicated poorer function. For every additional ED delirium duration day, the OARS ADL decreased by 0.63 (95%CI: −1.01 to −0.24) points. b. The relationship between ED delirium duration and 6-month cognition as measured by the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) adjusted for baseline IQCODE, age, baseline function, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, nursing home residence, central nervous system diagnoses, and incident delirium. Higher IQCODE scores indicated poorer cognition. For every ED delirium duration day, the patient’s 6-month IQCODE significantly increased by 0.06 points (95%CI: 0.01 to 0.10) indicating poorer 6-month cognition.

Of the 228 enrolled, 198 (86.8%) patients had a baseline IQCODE, 41 (18.0%) died within 6 months, 10 (4.4%) opted out of follow-up, and 16 (7.0%) were lost to follow-up, and 15 (6.6%) did not have a 6-month IQCODE leaving 116 patients available for the ED delirium duration and 6-month IQCODE analysis. For every ED delirium duration day, the patient’s 6-month IQCODE significantly increased by 0.06 points (95%CI: 0.01 to 0.10, Figure 2b) after adjusting for premorbid IQCODE and other confounders. This indicated that longer ED delirium duration was associated with poorer 6-month cognition.

The results of the sensitivity analyses can be seen in Supplemental Table S1. The β-coefficients for ED delirium duration for both the 6-month function and cognition models remained similar for all sensitivity analyses models.

Discussion

Our data suggest that delirium in the ED is a significant and life-altering event for the older patient, potentially threatening their independence and quality of life. We observed that delirium in the ED is not transient event and persists into hospitalization in 77% of cases and lasts a median of 3 days. The longer the ED delirium episode persisted during hospitalization (ED delirium duration), there was an incremental worsening in 6-month function and cognition. Based upon our findings, EDs should routinely monitor for delirium which is currently missed in the majority of cases.2 Furthermore, this data suggest that ED-based delirium treatment interventions should be developed to preserve the patient’s long-term function and cognition.

To our knowledge, only one study to date has evaluated the natural course of delirium in the ED. In 260 older ED patients, Hsieh et al. similarly observed that ED delirium resolved within 24 hours in 28% of cases.20 However, they were not able to quantify ED delirium duration or assess for delirium at hospital discharge as they followed these patients for two days. Most of what is known about delirium’s natural course is based upon studies conducted in the hospital setting, many of which enrolled patients in the hospital wards up to 48 hours after the admission. Based upon these studies, delirium can resolve within 24 hours in 40%21 and can persist to hospital discharge in 45% of delirious patients,22 with mean delirium duration of 7 days.21 Taken these data as a whole, delirium, regardless of clinical setting, is not a transient event and frequently persists to hospital discharge.

There is a dearth of data regarding the effect of delirium in the ED on long-term functional status and cognition. Vida et al. reported that delirium in the ED was not associated with 18-month function,23 and to our knowledge, no study has investigated ED delirium’s effect on long-term cognition. Most of what is known about delirium’s impact on these outcomes are from the in-hospital literature. The relationship between delirium and long-term function is equivocal as some of inpatient studies have observed a significant association8,24,25 while others have not.23,26,27 Such discordant observations may have occurred because these studies dichotomized delirium into a present-absent event and did not take into account delirium’s variable clinical course. For this reason, we quantified ED delirium’s duration and observed that it was significantly associated with poorer 6-month function. Studies have also shown that delirium during hospitalization is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in those who have baseline dementia28 and are critically ill.29 We also observed an association between delirium and poorer long-term cognition in more diverse older ED patient population who possess the full spectrum of pre-existing cognitive impairment and severity of illness.

Our study has several notable limitations. We did not enroll ED patients on the weekends or from 6PM to 4AM, and this may have introduced selection bias. There was a significant number of patients who refused (n=576) to participate in the study and these patients were slightly older, were less likely to be non-white, and slightly more likely to reside in a nursing home (Supplemental Table S2). Additionally, some of patients were excluded from the ED delirium duration and cognition analysis because of missing baseline or 6-month IQCODEs. These patients were probably more likely to be vulnerable, have underlying dementia, and be more functionally dependent, and their exclusion may have introduced additional selection bias. We used the modified bCAM which is 82% to 86% sensitive and only assessed for delirium once daily. This may have introduced misclassification bias, which can overestimate or underestimate our effect sizes. We also did not account for delirium severity or psychomotor subtypes, which may have further impacted 6-month function and cognition. The OARS ADL and IQCODE are informant-based questionnaires that were used to determine 6-month function and cognition, respectively. It is possible that informants who witnessed delirium episodes were more likely to rate the patient has having poorer 6-month function or cognition. However, delirium is frequently unrecognized in the ED and hospital settings,2,30 and informants are unlikely to be familiar with the link between delirium and adverse outcomes mitigating this source of potential informant bias. Inherent to most prospective cohort studies, unmeasured (e.g., malnutrition, drug exposure during hospitalization) and residual confounding (e.g., dementia) may have still existed. This study was conducted in a single center, urban, academic hospital and enrolled patients who were 65 years or older. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings and younger patients.

In conclusion, delirium in the ED is not a transient event and frequently persists into hospitalization in the majority of cases. Furthermore, longer ED delirium duration is associated with an incremental worsening of 6-month function and cognition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

Dr. Han and this study was funded by the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AG032355. This study was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06. Dr. Han was also supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number K12HL109019. Dr. Ely was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AG027472 and R01AG035117, and a Veteran Affairs MERIT award. Dr. Vasilevskis is supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AG040157. Drs. Vasilevskis, Schnelle, Dittus, and Ely are also supported by the Veteran Affairs Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, National Institutes of Health, and Veterans Affairs.

Sponsor’s Role

The funding agencies did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This abstract was presented at the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine 2016 Annual Meeting at New Orleans, LA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

JHH, EWE, JFS, and RDS conceived the trial and participated in the study design. JHH and EEV recruited patients and collected the data. RC, XL, and JHH analyzed the data. All authors participated in the interpretation of results. JHH drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the critical review and revision of the manuscript. JHH takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Table S1. Sensitivity Analyses.

Supplemental Table S2. Comparison of refusals and enrolled patients.

REFERENCES

- 1.Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S, et al. Delirium in the emergency department: an independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han JH, Eden S, Shintani A, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:391–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1204431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamantia MA, Messina FC, Hobgood CD, et al. Screening for Delirium in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Ann Emerg Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pompei P, Foreman M, Rudberg MA, et al. Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:809–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Keeffe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:174–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, et al. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:234–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:457–463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly KG, Zisselman M, Cutillo-Schmitter T, et al. Severity and course of delirium in medically hospitalized nursing facility residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han JH, Wilson A, Graves AJ, et al. A quick and easy delirium assessment for nonphysician research personnel. Am J Emerg Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.02.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286:2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, et al. Validity of an activities of daily living questionnaire among older patients in the emergency department. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holsinger T, Deveau J, Boustani M, et al. Does this patient have dementia? JAMA. 2007;297:2391–2404. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano S, Domingo J, Rodriguez-Garcia E, et al. Frequency of cognitive impairment without dementia in patients with stroke: a two-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2007;38:105–110. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251804.13102.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med. 1994;24:145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray SB, Bates DW, Ngo L, et al. Charlson Index is associated with one-year mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:530–536. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies : with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh SJ, Madahar P, Hope AA, et al. Clinical deterioration in older adults with delirium during early hospitalisation: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007496. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, et al. The course of delirium in older medical inpatients: a prospective study. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:696–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, et al. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing. 2009;38:19–26. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vida S, Galbaud du Fort G, Kakuma R, et al. An 18-month prospective cohort study of functional outcome of delirium in elderly patients: activities of daily living. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18:681–700. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray AM, Levkoff SE, Wetle TT, et al. Acute delirium and functional decline in the hospitalized elderly patient. J Gerontol. 1993;48:M181–M186. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.m181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz IR, Curyto KJ, TenHave T, et al. Validating the diagnosis of delirium and evaluating its association with deterioration over a one-year period. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:148–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, et al. Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2001;165:575–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryan DJ, O'Regan NA, Caoimh RO, et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open. 2013:3. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.