Abstract

Background and Aims

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma remains controversial. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of TCM regimens in HCC treatment.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) up to June 1, 2016, of the TCM treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma were systematically identified in PubMed, CNKI, Ovid, Embase, Web of Science, Wanfang, VIP, CBM, AMED, and Cochrane Library databases.

Results

A total of 1010 and 931 patients in 20 RCTs were randomly treated with add-on TCM therapy and conventional therapy, respectively. The additional use of TCM significantly improved six-month, one-year, two-year, and three-year overall survival rates in HCC cases (RR = 1.3, P = 0.01; RR = 1.38, P = 0.0008; RR = 1.44, P < 0.0001; RR = 1.31, P = 0.02, resp.). Add-on TCM therapy significantly increased PR rate and total response rate (tRR) and reduced PD rate compared to those in control group (34.4% versus 26.3%, RR = 1.30, P = 0.002; 41.6% versus 31.0%, RR = 1.30, P < 0.0001; and 16.6% versus 26.5%, RR = 0.64, P < 0.0001, resp.). Additionally, TCM combination therapy significantly increased the quality of life (QOL) improvement rate and reduced adverse events including leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia or erythropenia, liver injury, and gastrointestinal discomfort in HCC patients (all P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Add-on therapy with TCM could improve overall survival, increase clinical tumor responses, lead to better QOL, and reduce adverse events in hepatocellular carcinoma.

1. Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths. 70%~90% primary liver cancers occurring worldwide are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is the fastest growing cause of cancer-related death globally [1, 2]. Recent epidemiology data revealed that liver cancer might account for more cancer-related deaths worldwide [3]. HCC has a 5-year survival rate of only 14% approximately [4]. Most HCCs are diagnosed at an intermediate to advanced stage, at which point surgical treatment and/or chemical embolism are no longer feasible [5]. Therefore, to improve outcome of HCC patients, an alternative or novel approach is required.

Previous report showed a large prevalence of a diversity of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) clinical application for cancer patients [6]. Sufficient evidence has demonstrated that natural compounds with various types of medicinal ingredients can substantially inhibit tumor formation [7]. Many clinical articles have reported that TCM or TCM plus chemotherapy can significantly alleviate symptoms, stabilize tumor size, reinforce the constitution, enhance therapy tolerance and immunological function, obviously reduce the incidence rate of adverse events, and prolong patients' survival duration for unresectable HCC [8–11].

Unfortunately, reporting of RCTs on treatment of HCC with TCM is still in low quality, not meeting the CONSORT and TREND statement. High quality of evidence based on the existing clinical information is still unavailable [6, 12]. A recent meta-analysis also announced that many RCTs of TCM therapy in HCC are not, in fact, randomized [13]. Thus, only RCTs reported randomized methods were included in our current meta-analysis. The purpose of this study is to systematically review and meta-analyze data from RCTs for evidence on the efficacy and safety of add-on therapy with TCM in the treatment of HCC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

We searched PubMed, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) Database, Wanfang Database, Chinese Biomedical (CBM) Database, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database (VIP), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Ovid, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases until June 1, 2016. The following medical subject headings were used: “hepatocellular carcinoma;” “primary liver cancer;” “Traditional Chinese Medicine;” “alternative medicine;” “complementary medicine;” “Chinese herbal medicine;” “herb/herbal;” and “decotion/formulation.” Electronic searches were supplemented with manual searches of reference lists used in all of the retrieved review articles, primary studies, and abstracts from meetings to identify other studies not found in the electronic searches. Literature was searched by two authors (Z Yang and X Liao) independently.

Two authors independently selected trials and discussed with each other when inconsistencies were found. Articles that satisfy the following criteria were included: (1) for study types, RCTs with randomized method; (2) for participants, HCCs; (3) for interventions, TCMs compared with placebo or no treatment; in addition, any cointervention had to be the same in both groups except for the TCM formulation; (4) for outcome, overall survival and/or solid tumors responses; and (5) available full texts. If the duration and sources of study population recruitment overlapped by more than 30% in two or more papers by the same authors, we only included the most recent study or the study with the larger number of HCC patients. Studies were excluded if they meet the following criteria: (1) studies “so-called” randomized without randomized methods; (2) studies without control subjects or control participants receiving TCM treatment including herbal medicine and acupuncture; (3) studies reporting only laboratory values and/or symptom improvement rather than survival outcomes and clinical responses.

2.2. Data Extraction and Methodological Quality Assessment

Two researchers independently read the full texts and extracted the following contents: publication data; study design; sample size; patient characteristics; treatment protocol; and outcome measures. The methodological qualities of the included RCTs were assessed according to Cochrane Collaboration's Tool described in Handbook version 5.1.0 [14]. Two authors (Z Yang and X Liao) independently assessed quality, and inconsistency was discussed with other reviewer-authors (Y Yu and X Chen) who acted as arbiters.

2.3. Definitions

All the diagnosis should be according to guidelines. The primary outcome overall survival was defined as the time from HCC diagnosis until the death due to any cause. Solid tumor response is categorized as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), and CR + PR as a proportion for total response rate (tRR) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [15] or the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines [16, 17]. Karnofsky performance status (KPS) [18] and adverse events were also measured in our study.

2.4. Statistical Methods

The effect measures of interest were risk ratios (RRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity across studies was informally assessed by visually inspecting forest plots and formally estimated by Cochran's Q test in which chi-square distribution is used to make inferences regarding the null hypothesis of homogeneity (considered significant at P < 0.10). A rough guide to our interpretation of I2 was listed as follows:

0% to 40% shows that heterogeneity may not be important.

30% to 60% corresponds to moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90% exhibits substantial heterogeneity.

If the eligibility of some studies in the meta-analysis was uncertain because of missing information, a sensitivity analysis was performed by conducting the meta-analysis twice: in the first meta-analysis, all of the studies were included; in the second meta-analysis, only those that were definitely eligible were included. A fixed-effects model was used initially for our meta-analyses; a random-effects model was then used in the presence of heterogeneity. Description analysis was performed when quantitative data could not be pooled. Review Manager version 5.1 software was used for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study and Patient Characteristics

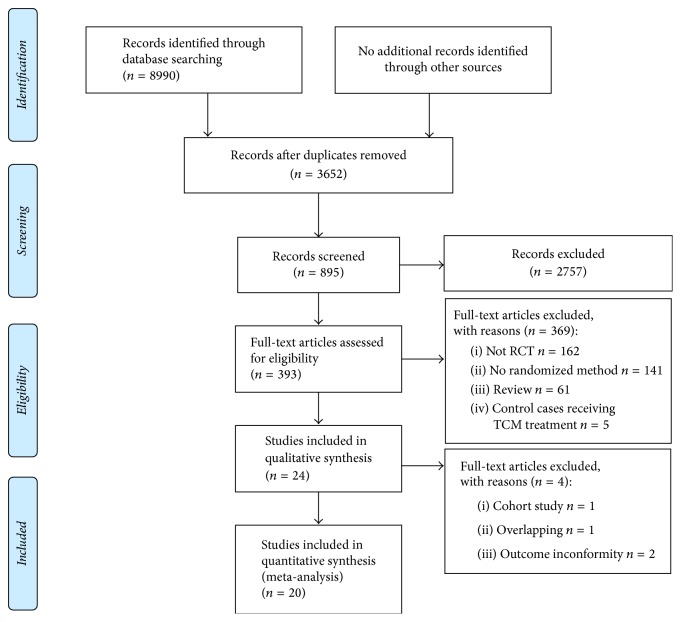

Totally, 8990 abstracts were reviewed; among these articles, 393 were retrieved that are closely related to the current subject. The study selection process was summarized in Figure 1. Finally, 20 RCTs [20–39] were included in this meta-analysis. The baseline characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Number of cases | Control regimen | Chemo times |

TCM intervention | TCM duration (days) | HCC staging |

Child-Pugh score |

KPS score |

Randomized method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | |||||||||

| Huang et al. 2001 [20] | 32 | 30 | Palliatively supporting therapy | None | Jianpi Xiaoji oral liquid | 30 | III, IV | A, B, C | ≥60 | Random number table |

| Huang et al. 2009 [21] | 40 | 37 | TACE | 1~2 | Ganji decoction | 28~42 | II, III | A, B | ≥60 | Random number table |

| Li et al. 2008 [22] | 50 | 46 | TACE | 2~7 | Chinese toad bufotoxin injection | 28~112 | OkudaI, II, III | A, B | ≥60 | Sealed envelopes |

| Li et al. 2013 [23] | 31 | 22 | TACE | 3 | Hydroxycamptothecin and Chinese herbal compound | 84 | II, III | NA | NA | Random number table |

| Li et al. 2016 [24] | 26 | 26 | TACE | NA | Aidi injection | 30 | III, IV | NA | 30~60 | Random number table |

| Lin et al. 2005 [25] | 52 | 33 | TACE | 2 | Hydroxycamptothecin and Shentao Ruangan pill | 56 | II, III | A, B | ≥60 | Randomized block |

| Ling et al. 2001 [26] | 162 | 151 | TACE/PEI | NA | Sisheng decoction/Chinese toad bufotoxin injection/norcantharidin tablets | Irregular | II, III | NA | NA | Sealed envelopes |

| Liu 2011 [27] | 32 | 30 | Palliatively supporting therapy | None | Chinese herbal compound | 21 | III, IV | A, B, C | ≥60 | Random number table |

| Liu and Lü 2016 [28] | 53 | 53 | TACE + PMCT | 3 | Chinese herbal compound | 90~135 | NA | A, B | NA | Random number table |

| Lu 2008 [29] | 69 | 69 | TACE | NA | Aidi injection | 20 | NA | NA | 60~90 | Draw method |

| Lü et al. 2014 [30] | 63 | 63 | TACE | NA | Shenyi capsules | 60 | NA | NA | 60~90 | Random number table |

| Min and Zhou 2011 [31] | 23 | 22 | Palliatively supporting therapy | None | Chinese herbal compound | 84 | II, III | A, B | 72 ± 8 | Random number table |

| Ren and Cheng 2004 [32] | 104 | 68 | TACE | NA | Chinese herbal compound | ≥90 | II, III | NA | NA | Random number table |

| Shao et al. 2001 [33] | 30 | 30 | TACE | 2~10 | Chinese herbal compound | 180~300 | II, III | NA | NA | According to hospitalized date |

| Shi and Tang 2013 [34] | 42 | 56 | TACE | NA | Kang'ai injection and Carapacis Trionycis Bolus | 56 | NA | A, B | ≥60 | Random number table |

| Tian et al. 2008 [35] | 49 | 48 | TACE | NA | Chinese herbal compound | 28 | II, III | A, B | ≥60 | Randomized block, single blind |

| Xie et al. 2014 [36] | 34 | 34 | TACE | NA | Chinese herbal compound | 40 | NA | A, B | ≥60 | Draw method |

| Yang et al. 2011 [37] | 30 | 30 | TACE | NA | Aidi injection | 30 | NA | A, B, C | ≥70 | Sealed envelopes |

| Yi et al. 2008 [38] | 28 | 23 | TACE | 3 | Kang'ai injection | 45 | II, III | NA | ≥60 | Sealed envelopes |

| Zhong et al. 2014 [39] | 60 | 60 | Hepatectomy | None | Chinese herbal compound | 365 | I~IIIa | A, B | NA | Sealed envelopes |

TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; PMCT, percutaneous microwave coagulation therapy; KPS, Karnofsky performance status.

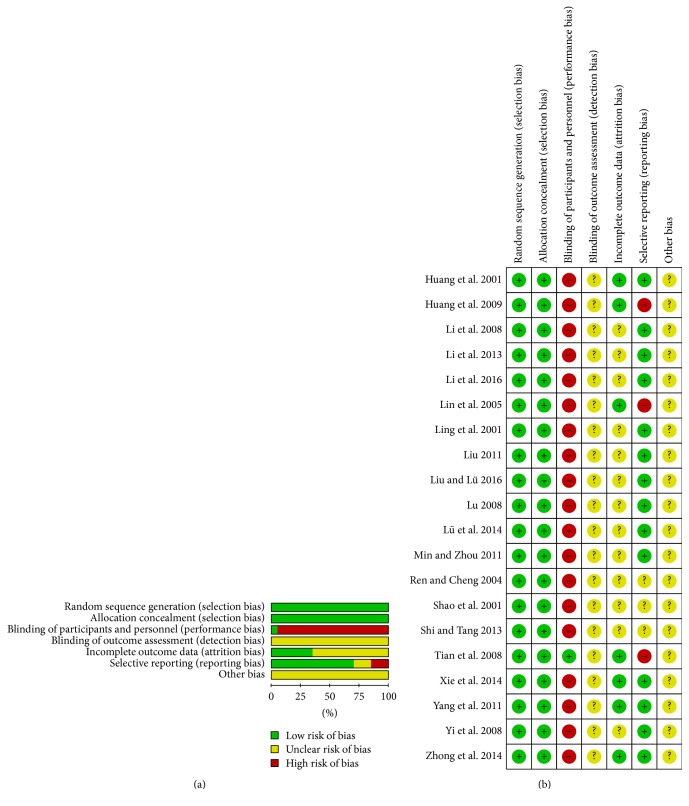

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methods of randomization were described adequately in all studies [20–39], which were considered as random number table [20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30–32, 34], sealed envelopes [22, 26, 37–39], randomized block [25, 35], draw method [29, 36], and randomization according to hospitalized date [33]. We hence considered low risks in terms of selection bias. Except for study reported by Tian et al. [35], blind-methods of other studies were not available, which were considered high risk in terms of performance bias. Detection bias was unclear in all studies with no presenting of blinding of outcome assessment. Less than 15% of participants were lost to follow-up in the three studies [20, 21, 25, 35–37, 39]; these parameters were considered low risk in terms of incomplete outcome data. Selective reporting was found in three studies [21, 25, 35] because these researches failed to present the clinical data of participants in ITT analysis. Other potential biases were unclear in these trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph (a) and risk of bias summary (b).

3.3. Overall Survival

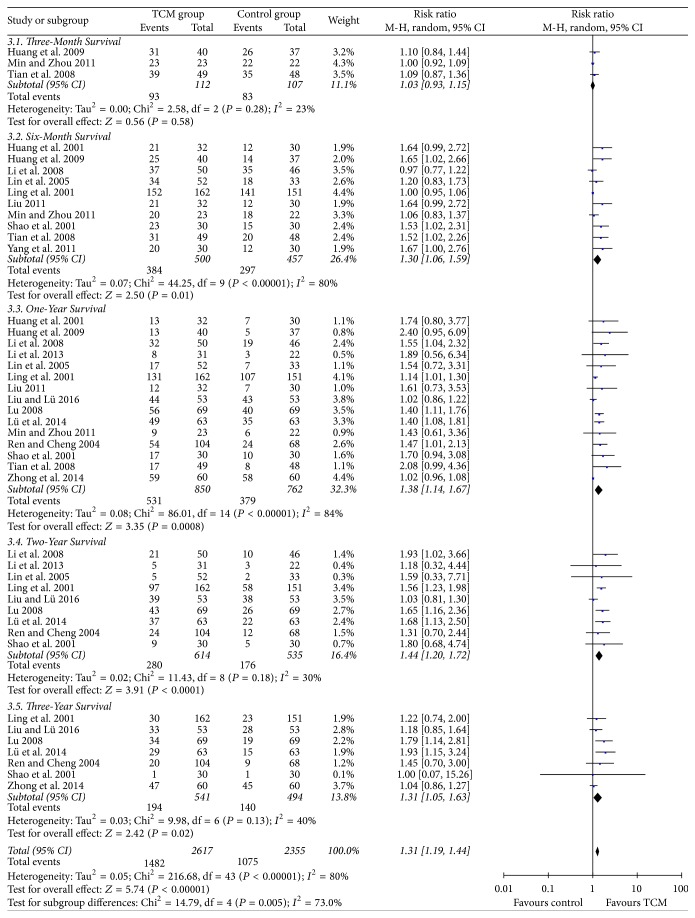

No heterogeneity was found among the included studies [21, 31, 35], which reported three-month survival in the two groups. No significance of three-month survival was found in HCC patients between TCM group and control group (RR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.93–1.15, P = 0.58, Figure 3(3.1)). Heterogeneity was significant when we compared six-month survival and one-year survival (P < 0.00001, I2 = 80% and P < 0.00001, I2 = 84%, resp.). As shown in Figure 3, TCM therapy could significantly prolong six-month survival and one-year survival of HCC patients compared to control (RR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.06–1.59, and P = 0.01 and RR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.14–1.67, and P = 0.0008, resp., Figure 3(3.2 and 3.3)).

Figure 3.

Overall surviving comparison.

No heterogeneity was found between studies comparing two-year survival and three-year survival between the two groups (P = 0.18, I2 = 30% and P = 0.13, I2 = 40%, resp.). Meta-analysis of RCTs [22, 23, 25, 26, 28–30, 32, 33] using a random-effects model showed that the two-year survival rate of HCC patients in TCM group was significantly higher than that in control group [280/614 (45.6%) versus 176/535 (32.9%), RR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.20–1.72, and P < 0.0001, Figure 3(3.4)]. Similarly, the three-year survival rate of HCC patients receiving TCM therapy was significantly higher than that in control group [194/541 (35.9%) versus 140/494 (28.3%), RR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.05–1.63, and P = 0.02, Figure 3(3.5)].

3.4. CR, PR, SD, PD, and tRR

As shown in Table 2, no heterogeneity was among comparisons of CR, PR, SD, PD, and tRR. Thus, a fixed-effects model was used. The CR rate of HCC patients in TCM group was higher than that in control group, but no statistical difference was found (RR = 1.47, 95% CI = 0.96–2.24, and P = 0.07, Figure S1; see Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3428253). However, meta-analysis of RCTs [20, 22–25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] demonstrated that HCC patients receiving TCM therapy achieved significantly higher PR rate and tRR than those in control group (34.4% versus 26.3%, RR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.10–1.53, and P = 0.002 and 41.6% versus 31.0%, RR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.16–1.53, and P < 0.0001, resp., Figure S2 and Figure S5). In contrast, HCC patients in TCM group suffered from lower PD rate significantly than those in control group (16.6% versus 26.5%, RR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.52–0.80, and P < 0.0001, Figure S4). No statistical significance was found when we compared SD rate of HCC patients between TCM group and control group (42.6% versus 43.7%, RR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.84–1.08, and P = 0.47, Figure S3).

Table 2.

Solid tumor responses comparisons of HCC patients.

| Comparisons | Studies | Groups | Clinical responses (%) | Heterogeneity | RR | 95% CI | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi2 | df | P | I 2 (%) | |||||||

| Complete response (CR) | [22, 23, 29, 30, 32, 34–36] | Treatment | 44/442 (10.0) | 3.07 | 7 | 0.88 | 0 | 1.47 | 0.96–2.24 | 0.07 |

| Control | 26/406 (6.4) | |||||||||

| Partial response (PR) | [20, 22–25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] | Treatment | 210/610 (34.4) | 9.96 | 12 | 0.62 | 0 | 1.30 | 1.10–1.53 | 0.002 |

| Control | 145/551 (26.3) | |||||||||

| Stable disease (SD) | [20, 22–25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] | Treatment | 260/610 (42.6) | 15.89 | 12 | 0.2 | 24 | 0.95 | 0.84–1.08 | 0.47 |

| Control | 241/551 (43.7) | |||||||||

| Progressive disease (PD) | [20, 22–25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] | Treatment | 101/610 (16.6) | 9.22 | 12 | 0.68 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.52–0.80 | <0.0001 |

| Control | 146/551 (26.5) | |||||||||

| Total response rate (tRR) | [20, 22–25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] | Treatment | 254/610 (41.6) | 13.56 | 12 | 0.33 | 12 | 1.3 | 1.16–1.53 | <0.0001 |

| Control | 171/551 (31.0) | |||||||||

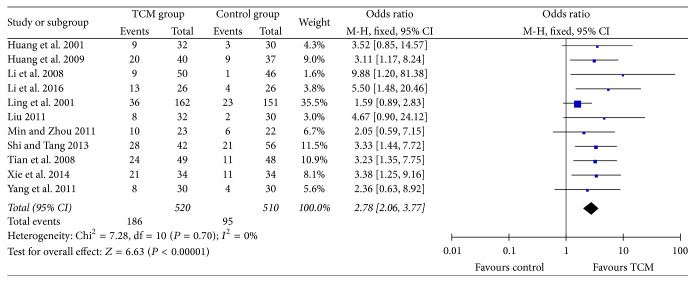

3.5. Quality of Life (QOL)

In this meta-analysis, KPS scores increasing more than 10 after treatment compared to that before treatment was considered improvement in QOL. 11 RCTs [20–22, 24, 26, 27, 31, 34–37] reported QOL assessment according to KPS scores, with no significance of heterogeneity which existed (P = 0.70, I2 = 0%). As shown in Figure 4, the QOL improvement rate of HCC patients in TCM group was significantly higher than that in control group [186/520 (35.8) versus 95/510 (18.6), RR = 2.78, 95% CI = 2.06–3.77, and P < 0.00001].

Figure 4.

Improvement rate of quality of life according to KPS scores.

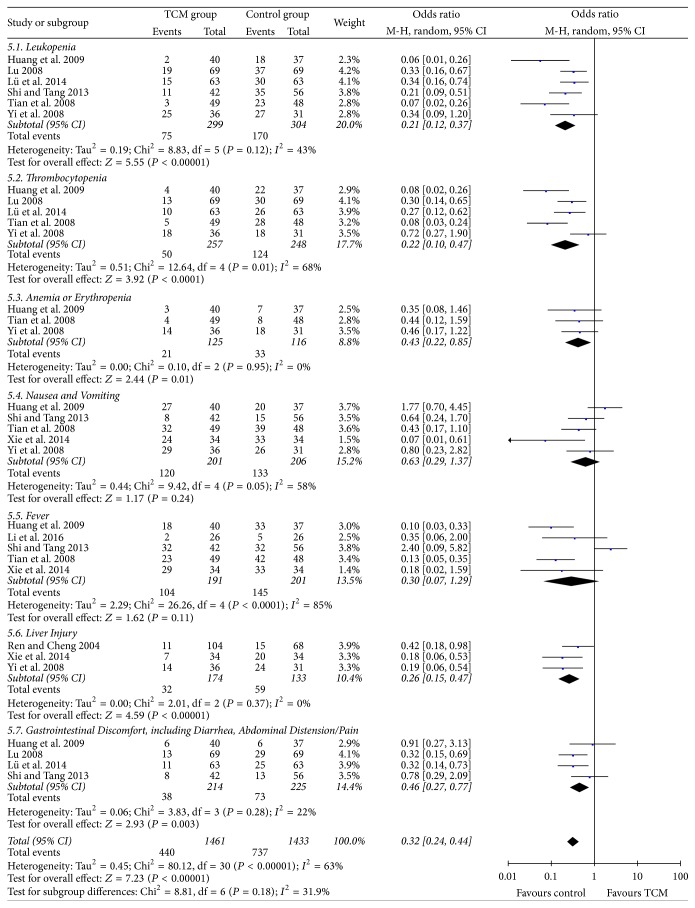

3.6. Adverse Events

Nine RCTs [21, 24, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38] reported the adverse events incidence of HCC patients. The most frequent adverse events were leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia/erythropenia, nausea, vomiting, fever, liver injury, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Meta-analysis indicated that HCC patients in control group had significantly higher risk of suffering from leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia/erythropenia, liver injury, and gastrointestinal discomfort than those receiving TCM therapy (55.9% versus 25.1%, 50.0% versus 19.5%, 28.4% versus 16.8%, 44.4% versus 18.4%, and 32.4% versus 17.8%, respectively, all P < 0.05, Figure 5). No statistical significance of nausea/vomiting and fever was found between the two groups (P = 0.24 and P = 0.11, resp., Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Adverse events incidence.

4. Discussion

Most newly diagnosed HCC cases are at an intermediate advanced stage, and the therapeutic options are limited to palliative approaches using TACE or chemotherapeutic agents [5, 40]. Even worse, many patients poorly respond to TACE or suffer from poor outcomes and side effects with conventional systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy [40], leading to disappointing results of systemic chemotherapies and a poor prognosis. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies are essential to improve the clinical management of patients with HCC.

With a long history of clinical use, essential components of TCM have gradually become a common used treatment for cancer in China [41]. In particular, TCM has been used to treat HCC extensively and it can be used throughout the whole course of HCC [42]. In the past decades, many compounds derived from Chinese herbals of both preclinical and clinical researches have shown promising potentials in novel anti-HCC natural product development [43]. Previous studies indicated that the effect of TCM has targeted the stimulation of the host immune response for cytotoxic activity against liver cancer by inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis of tumor cells [7, 44], thereby improving survival and alleviating palliative approaches-related side effects in HCC patients [45–47].

This meta-analysis summarized evidence on the effects of TCM therapy for HCC patients, on top of conventional treatment. For survival, it is observed that the additional use of TCM significantly improved six-month, one-year, two-year, and three-year survival rates in HCC cases. Additionally, TCM combination therapy could increase PR rate and tRR and reduce PD rate in this population. Given above, results from our study demonstrated add-on benefits of TCM in improving outcomes of HCC patients. As the molecular pathogenesis of HCC is highly associated with multigene, multifactor, and multistep processes and is quite complicated, add-on TCM therapy combined with other therapeutic options has a promising potential for its multilevel, multitarget, and coordinated intervention effects against HCC [43]. Many active compounds from TCM have shown their noticeable potentials in inhibiting the promotion, proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis of HCC [43, 44], which may contribute to good tumor response and survival in clinical practice. Although the mechanisms of TCM components in anti-HCC were well reviewed before [43], further in-depth mechanistic studies and well-designed clinical trials are warranted.

Previous work has suggested that QOL is an important predictor of survival for cancer patients [48]. Although more sophisticated approaches of QOL measurement were developed, the KPS scores are still widely recognized as a tool for the assessment of the functional status of cancer patients and highly reliable [49]. Based on the evidence we identified, TCM combination therapy may be considered as an alternative option to improve QOL in HCC patients. Previously, KPS as a predictor of survival has been demonstrated in patients with different kind of cancers [48, 49], and few studies focused on the relationship between KPS scores and HCC survival. Whether KPS has a role in predicting HCC outcomes should be focused on in future studies.

Evidence of this meta-analysis also showed that the combination of TCM and chemotherapy significantly reduced adverse events including leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia or erythropenia, liver injury, and gastrointestinal discomfort in HCC patients. However, because of the toxic effects of chemotherapy and anticancer drugs on normal cells and tissues, anticancer drugs and approaches cause many side effects and adverse events with various symptoms, including hematocytopenia, gastrointestinal discomfort (nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and diarrhea), and liver injury. These side effects often influence patients' QOL and sometimes make the chemotherapy discontinued [50, 51]. Consistent with our results, growing evidences suggest that TCM appears to have beneficial effects for prevention and improvement of several chemotherapy-induced side effects [52, 53], leading to better outcomes in this population.

This meta-analysis had the following limitations. First, majority of the included studies had small samples, with mid- to low-quality designs. Second, all included studies were conducted in China. According to our experience, only positive results are published in Chinese medical journals. We cautiously drew the conclusion that publication bias might have been present in this meta-analysis. Third, most included studies failed to address blinding assessment, which may influence the objectivity of HCC outcomes. High-quality, well-designed, large sample trials focused on the efficacy and safety of TCM therapy for HCC should be performed in the future.

In conclusion, add-on therapy with TCM could improve overall survival, increase clinical tumor responses, and reduce adverse events in hepatocellular carcinoma. Previous surveys indicated that the trend of TCM use in patients with cancer is on the rise. Surveys have also found that many cancer patients were more inclined to use TCM therapies in combination with conventional therapy rather than in lieu of conventional therapy [54]. Thus, investigating the combined use of TCM and conventional therapy in the oncology setting is urgently essential for practitioners. Evidence-based approaches in the clinic have to be supplemented by experimental studies to unravel cellular and molecular modes of action of TCM treatments [45].

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Complete response (CR) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S2: Partial response (PR) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S3: Stable disease (SD) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S4: Progressive disease (PD) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S5: Total response rate (tRR) comparison between TCM group and control group.

Acknowledgments

This work was mainly sponsored by Youth Physician Training Grant Program in Shanghai 2015 (Zongguo Yang) and Shanghai Sailing Program (17YF1416000).

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Zongguo Yang and Xian Liao have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2012;56(4):908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre L. A., Bray F., Siegel R. L., Ferlay J., Lortet-Tieulent J., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allemani C., Weir H. K., Carreira H., et al. Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2) The Lancet. 2015;385(9972):977–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam W., Jiang Z., Guan F., et al. PHY906(KD018), an adjuvant based on a 1800-year-old Chinese medicine, enhanced the anti-tumor activity of Sorafenib by changing the tumor microenvironment. Scientific Reports. 2015;5, article 9384 doi: 10.1038/srep09384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Serag H. B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(12):1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X., Yang G., Li X., et al. Traditional Chinese medicine in cancer care: a review of controlled clinical studies published in Chinese. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060338.e60338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin A. R. M. R., Kucuk O., Khuri F. R., Shin D. M. Perspectives for cancer prevention with natural compounds. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(16):2712–2725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guan D., Fang Z. Advances in TCM treatment of primary hepatocarcinoma. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2000;20(3):223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng M.-B., Cui Y.-L., Guan Y.-S., et al. Traditional Chinese medicine plus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(8):1027–1042. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng M.-B., Wen Q.-L., Cui Y.-L., She B., Zhang R.-M. Meta-analysis: Traditional Chinese medicine for improving immune response in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Explore. 2011;7(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P. A clinical analysis of strengthening integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine therapy for prevention and treatment of liver cancer. Journal of Clinical Hepatology. 2015;32(4):615–617. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y., Zhang R.-M., Chang J. Quality assessment of the report of randomized controlled trials on treatment of liver carcinoma with traditional Chinese medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine. 2008;28(7):588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu P., Dugoua J. J., Eyawo O., Mills E. J. Traditional Chinese medicines in the treatment of hepatocellular cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;28(1, article 112) doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. ((Updated March 2011)). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller A. B., Hoogstraten B., Staquet M., Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47(1):207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therasse P., Arbuck S. G., Eisenhauer E. A., et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogaerts J., Ford R., Sargent D., et al. Individual patient data analysis to assess modifications to the RECIST criteria. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(2):248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yates J. W., Chalmer B., McKegney F. P. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky performance status. Cancer. 1980;45(8):2220–2224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800415)45:8<2220::aid-cncr2820450835>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z. F., Li H. Z., Zhang Z. J., et al. Clinical study on Jianpi Xiaoji oral liquid for improvement of life quality in 32 cases of late liver cancer. Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2001;45(10):754–756. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang X. Q., Tian H. Q., Liang G. W., Chen X. Z., Shen Q. P. Study of combined treatment with traditional Chinese medicine for advanced primary hepatocarcinoma. Chinese Journal of Clinical Oncology and Rehabilitation. 2009;16(1):57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q., Sun B. M., Peng Y. H., Fan Z. Z., Sun J. Clinical study on the treatment of primary liver cancer by cinobufotain combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Universitatis Traditionis Medicalis Sinensis Pharmacologiaeque Shanghai. 2008;22(2):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J. C., Fan D. Y., Liu P. Z., Luo Y. C., Gao W. K., Liang H. J. Integrative medicine therapy for 32 cases hepatocellular carcinoma with advanced stage. Zhong Yi Yan Jiu. 2013;26(1):21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y. Y., Zhou L. X., Ren R. J., Liu Y. L. Clinical observation of traditional Chinese medicine therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with late stage. Chinese Journal of Modern Drug Application. 2016;10(6):243–244. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin L.-Z., Zhou D.-H., Liu K., Wang F.-J., Lan S.-Q., Ye X.-W. Analysis on the prognostic factors in patients with large hepatocarcinoma treated by shentao ruangan pill and hydroxycamptothecine. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2005;25(1):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling C. Q., Chen Z., Zhu D. Z., et al. Integrative medicine therapy for 313 cases hepatocellular carcinoma. Shijie Hua Ren Xiao Hua Za Zhi. 2001;9(1):114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y. M. Self-designed Gan'ai decotion improves quality of life in 32 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma with advanced stage. Guang Ming Zhong Yi. 2011;26(9):1822–1823. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H., Lü W. Z. Application value of traditional Chinese and western medicine in the treatment of postoperative recurrence of liver cancer. The Practical Journal of Cancer. 2016;31(3):493–495. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu X. C. Clinical study on treatmeant of primary liver cancer with portal vein tumor thrombus by compositive integrated traditional chinese and clinical medicine. China Journal of Modern Medicine. 2008;18(21):3163–3167. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lü X C., Zhao P., Li L. Y., Liu J. L., Xia Z. S. Clinical study on intermediate or advanced primary liver cancer by connective and compositive treatment of traditional Chinese and western medicine. China Journal of Modern Medicine. 2014;24(36):61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min L., Zhou R. Y. Impact of Enforcing spleen and nourishing kidney herbs on thyroid hormones and clinical efficacy of hepatocellular carcinoma patients after hepatectomy. Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2011;52, supplement:96–98. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren H. P., Cheng L. Clinical observation of nourishing spleen and dredging Qi herbs combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy for middle-advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2004;24(9):838–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao Z. X., Cheng Z. G., Yi X. E., et al. Clinical study on treatment of middle-advanced stage liver cancer by combined treatment of hepatic artery chemoembolization with Gan'ai no. I and no. II. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2001;21(3):168–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi D. B., Tang T. T. Clinical observation of palliative therapy with traditional Chinese medicine for middle-advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Liaoning Zhong Yi Za Zhi. 2013;40(9):1855–1856. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian H. Q., Liang G. W., Huang X. Q., et al. Prospective randomized controlled study on complex treatment of traditional Chinese medicine to advanced primary hepatocarcinoma. China Medical Herald. 2008;5(31):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Y. X., Wang S. H., Yang J. Q., et al. Yao medicine Quanti Tang combined with TACE in treating primary liver cancer randomized parallel controlled study. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Internal Medicine. 2014;29(4):74–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z. J., Deng C. M., Liu J. B., Huang C. J. Influence on the life quality and immune function of liver cancer patients treated with Chinese medicine combined with western medicine. China Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2011;26(8):907–909. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi J.-Z., Xie Y.-C., Deng X.-H. Clinical observation on the effect of Kang'ai injection combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization on hepatocellular carcinoma in 36 patients. Tumor. 2008;28(11):997–1000. doi: 10.3781/j.issn.1000-7431.2008.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong C., Li H.-D., Liu D.-Y., et al. Clinical study of hepatectomy combined with Jianpi Huayu therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014;15(14):5951–5957. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.14.5951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pircher A., Medinger M., Drevs J. Liver cancer: targeted future options. World Journal of Hepatology. 2011;3(2):38–44. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i2.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu M., Lu P., Shi L., Li S. Traditional Chinese patent medicines for cancer treatment in China: a nationwide medical insurance data analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(35):38283–38295. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu M.-C. Traditional Chinese medicine in prevention and treatment of liver cancer: function, status and existed problems. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2003;1(3):163–164. doi: 10.3736/jcim20030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu Y., Wang S., Wu X., et al. Chinese herbal medicine-derived compounds for cancer therapy: a focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;149(3):601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ling C.-Q., Yue X.-Q., Ling C. Three advantages of using traditional Chinese medicine to prevent and treat tumor. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2014;12(4):331–335. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(14)60038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konkimalla V. B., Efferth T. Evidence-based Chinese medicine for cancer therapy. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(2):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ling C.-Q., Wang L.-N., Wang Y., et al. The roles of traditional Chinese medicine in gene therapy. Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2014;12(2):67–75. doi: 10.1016/s2095-4964(14)60019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao Y.-H., Lin C.-C., Lai H.-C., Chiang J.-H., Lin J.-G., Li T.-C. Adjunctive traditional Chinese medicine therapy improves survival of liver cancer patients. Liver International. 2015;35(12):2595–2602. doi: 10.1111/liv.12847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang S. S., Scott C. B., Chang V. T., Cogswell J., Srinivas S., Kasimis B. Prediction of survival for advanced cancer patients by recursive partitioning analysis: role of Karnofsky performance status, quality of life, and symptom distress. Cancer Investigation. 2004;22(5):678–687. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200032911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evers P. D., Logan J. E., Sills V., Chin A. I. Karnofsky Performance Status predicts overall survival, cancer-specific survival, and progression-free survival following radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma. World Journal of Urology. 2014;32(2):385–391. doi: 10.1007/s00345-013-1110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeSantis C. E., Lin C. C., Mariotto A. B., et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64(4):252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akin S., Can G., Aydiner A., Ozdilli K., Durna Z. Quality of life, symptom experience and distress of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(5):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohnishi S., Takeda H. Herbal medicines for the treatment of cancer chemotherapy-induced side effects. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2015;6, article 14 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tao W., Luo X., Cui B., et al. Practice of traditional Chinese medicine for psycho-behavioral intervention improves quality of life in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6(37):39725–39739. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ladas E. J., Kelly K. M. Milk thistle: is there a role for its use as an adjunct therapy in patients with cancer? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(3):411–416. doi: 10.1089/107555303765551633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Complete response (CR) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S2: Partial response (PR) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S3: Stable disease (SD) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S4: Progressive disease (PD) rate comparison between TCM group and control group.

Figure S5: Total response rate (tRR) comparison between TCM group and control group.