Abstract

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a life-threatening neurological disorder associated with the use of antipsychotic medications. Many of its classic signs, such as fever and altered mental status, are nonspecific in trauma intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and its rarity makes it a difficult diagnosis in this population. However, delays in treatment can be costly both in terms of hospital resources and patient outcomes. We herein report a case of a 54-year-old trauma patient with NMS precipitated by a combination of cocaine withdrawal and neuroleptic medications. Few cases of NMS in the intubated polytrauma patient have been described in the literature previously. Given the poor outcomes associated with this disorder, ICU patients would benefit from risk stratification and avoidance of neuroleptic medications in those at highest risk for NMS, particularly patients who are withdrawing from dopaminergic agents.

Key Words: Bromocriptine, dantrolene, management, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, polytrauma, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is an emergent neurological condition classically manifested by the tetrad of altered mental status, muscular rigidity, hyperthermia, and dysautonomia. It occurs in 0.02%–3% of patients taking neuroleptics, and mortality is as high as 10%–20%.[1,2,3] The diagnosis is made primarily by clinical criteria. The absence of a definitive diagnostic test for NMS complicates its recognition in intubated polytrauma patients, whose comorbidities reasonably lead intensivists to initially evaluate other etiologies of fever and altered mental status. We present the case of an intubated cocaine abuser whose course was complicated by NMS, which was triggered by minimal neuroleptic use beyond his home medications.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old male presented to our institution following a motor vehicle collision. Glasgow Coma Scale was initially 13 but declined shortly after presentation. He was intubated and admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (ICU). Imaging was significant for a C1 transverse foramen fracture, bilateral rib fractures, and pulmonary contusions.

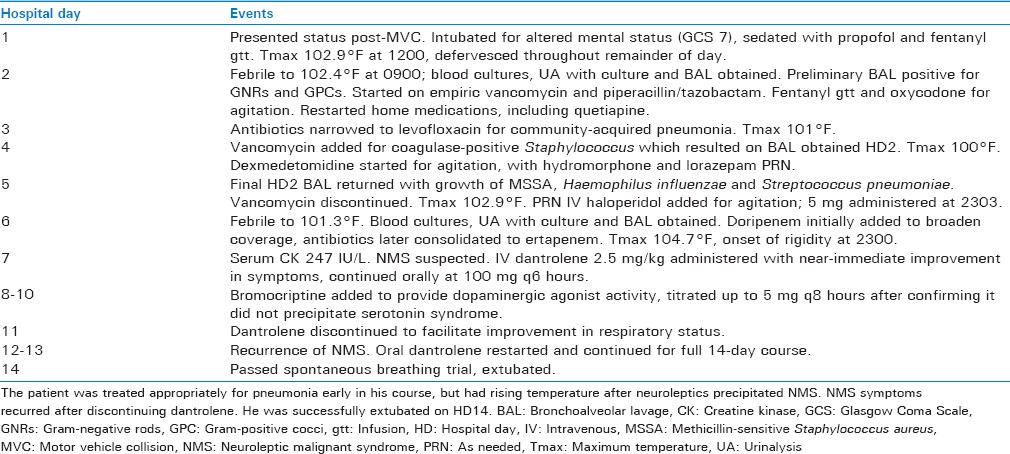

His initial course is summarized in Table 1. He became febrile shortly after admission. Lower respiratory culture was consistent with a polymicrobial pneumonia, for which he was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Table 1.

Hospital course from admission through extubation

On hospital day 2, his family provided additional history of significant active crack cocaine use. He was restarted on his home medications, which included quetiapine 400 mg at bedtime and mirtazapine 30 mg at bedtime. He had persistent, intermittent agitation which was difficult to control despite opioids, dexmedetomidine, and lorazepam.

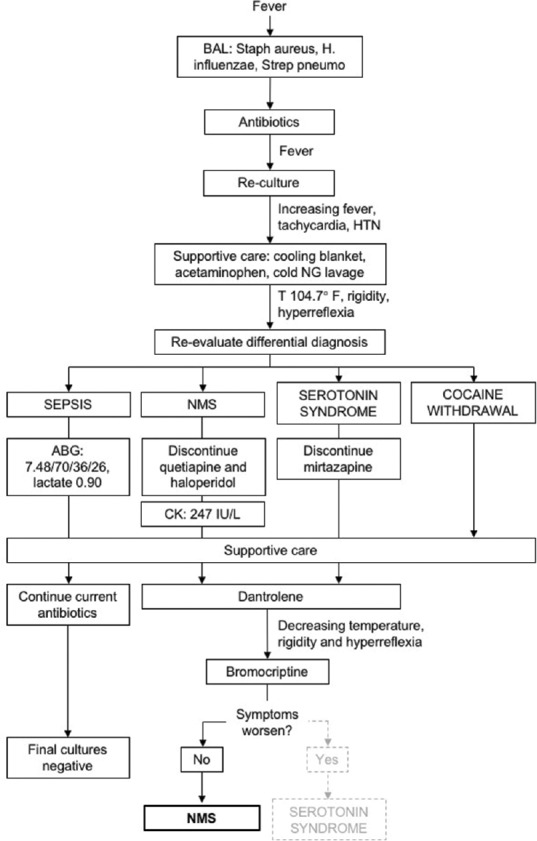

Overnight on hospital day 5, he received a dose of intravenous haloperidol 5 mg for agitation. He was febrile the following day to 102.2°F–104.7°F despite acetaminophen, a cooling blanket, and ice saline gastric lavage. By that evening, he developed tachycardia and hypertension with diffuse lead-pipe rigidity, hyperreflexia, and two-beat clonus. The differential diagnosis was therefore broadened to include sepsis, NMS, serotonin syndrome, and cocaine withdrawal [Figure 1]. Serum creatine kinase (CK) was 247 IU/L. He received IV dantrolene 2.5 mg/kg for possible NMS. Quetiapine, mirtazapine, and haloperidol were discontinued. Within 30 min of dantrolene administration, the dysautonomia, rigidity, and hyperreflexia had resolved, and temperature had downtrended. Blood, urine, and lower respiratory cultures were also sent to evaluate for sepsis.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the diagnosis of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Pneumonia was diagnosed on hospital day 2, so uncontrolled sepsis was the working diagnosis for the patient's persistent fever. As his temperature climbed despite antibiotics, the differential was broadened and he was diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome

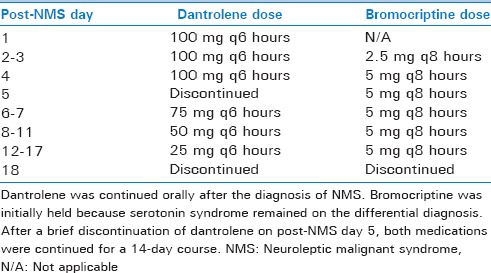

He continued on maintenance oral dantrolene the following day (post-NMS day 1) with resolution of rigidity and improvement in his fever curve. Bromocriptine was added on post-NMS day 2. Dantrolene was discontinued on post-NMS day 5 to facilitate extubation, but rigidity and hyperreflexia recurred within 24 h. It was therefore restarted for a tapered 14-day course from that point [Table 2]. He passed a spontaneous breathing trial on post-NMS day 8 and was extubated.

Table 2.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome treatment course

The patient's mental status returned to baseline, and he had no further recurrence of symptoms despite cautious resumption of quetiapine 50 mg QHS on post-NMS day 22. He was discharged on post-NMS day 29.

DISCUSSION

Even among patients receiving neuroleptic medications, NMS is an uncommon disease.[3,4] Its pathophysiology is not well-defined, but it likely involves blockade of the hypothalamic and nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathways and/or the peripheral neuromuscular system.[5,6] As such, NMS can be precipitated by either administration of anti-dopaminergic medications or withdrawal of dopaminergic agents.[1,2,3] In our patient, a combination of both contributed to NMS onset. This case illustrates two unique aspects of an already rare disease: The diagnosis of NMS in a polytrauma patient with multiple potential fever sources after a single low dose of haloperidol and the management of NMS in an intubated patient.

NMS is diagnosed by the recognition of its classic tetrad, but fever, altered mental status, rigidity, and autonomic instability are nonspecific in ICU patients. Its scarcity would reasonably lead the intensivist to explore other, more common, etiologies first. However, the consequences of a missed diagnosis of NMS are severe, with high rates of morbidity and mortality.[1] Serum CK can assist with the diagnosis, but it is nonspecific unless greatly elevated to higher than 1000 IU/L.[4] The diagnosis in this case was further complicated by the fact that the patient had received a single dose of haloperidol. Previous reports indicate that NMS in traumatic brain injury patients is typically triggered by at least 10 mg of haloperidol, with most patients receiving ≥30 mg.[7] It is important for the intensivist to have NMS on the differential diagnosis for all patients who may be withdrawing from dopaminergic agonists, which must be considered in trauma patients for whom a complete history is not available.[8] Moreover, it must be remembered that neuroleptics have side effects even at home doses, and their use during a period of cocaine withdrawal can lead to an exacerbation of withdrawal symptoms, NMS, or even death.[9]

The second interesting component of this case was the management of an intubated patient with NMS. The tenets of NMS treatment are supportive care and cessation of the precipitating agents.[5] Bromocriptine can assist by acting as a dopaminergic agonist, and dantrolene reduces symptoms by directly inhibiting muscular activity.[5,6] The degree of dantrolene's effect on the diaphragm is unclear, but there are reports that its use can contribute to respiratory failure.[10] As a result, we feared that it could complicate extubation in a patient with other risk factors for reintubation, including rib fractures, pulmonary contusions, and pneumonia. We briefly attempted to discontinue dantrolene to facilitate extubation, but NMS symptoms quickly recurred. Therefore, the optimal dantrolene treatment is a full tapered course of at least 10 days, even in the intubated polytrauma patient.[6] NMS treatment should not be interrupted to attempt extubation, and dantrolene use should not preclude extubation if the patient otherwise meets clinical criteria.

In summary, prompt recognition of NMS is critical to avoid adverse outcomes, but its rarity means it will seldom be at the top of an intensivist's differential diagnosis. The optimal solution to this conundrum is prevention. Intensivists should risk-stratify patients with the highest likelihood of developing NMS and avoid neuroleptics in this population whenever possible. If neuroleptics must be prescribed, the treating physician must always consider this fatal syndrome as a possible source of fever and altered mental status.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seitz DP, Gill SS. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome complicating antipsychotic treatment of delirium or agitation in medical and surgical patients: Case reports and a review of the literature. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:8–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shalev A, Hermesh H, Munitz H. Mortality from neuroleptic malignant syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velamoor VR. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Recognition, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 1998;19:73–82. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199819010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levenson JL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1137–45. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.10.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adnet P, Lestavel P, Krivosic-Horber R. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:129–35. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:389–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellamy CJ, Kane-Gill SL, Falcione BA, Seybert AL. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in traumatic brain injury patients treated with haloperidol. J Trauma. 2009;66:954–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818e90ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosten TR, Kleber HD. Rapid death during cocaine abuse: A variant of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome? Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1988;14:335–46. doi: 10.3109/00952998809001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akpaffiong MJ, Ruiz P. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: A complication of neuroleptics and cocaine abuse. Psychiatr Q. 1991;62:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01958798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javed M, Bogdanov A. Oral dantrolene and severe respiratory failure in a patient with chronic spinal cord injury. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:855–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]